Abstract

Aim: To investigate the efficacy and tolerability of a cream (Rilastil Xerolact PB) containing a mixture of prebiotics and postbiotics, and to validate the PRURISCORE itch scale in the management of atopic dermatitis.

Methods: The study is based on 396 subjects of both sexes in three age groups (i.e., infants, children, adults) suffering from mild/moderate Atopic Dermatitis, recruited from 8 European countries and followed for 3 months.

Results: The product demonstrated good efficacy combined with good/very good tolerability in all age groups. In particular, SCORAD, PRURISCORE and IGA scores decreased significantly over the course of the study. The PRURISCORE was preferred to VAS by the vast majority of patients.

Conclusion: Even though the role of prebiotics and postbiotics was not formally demonstrated since these substances were part of a complex formulation, it can be reasonably stated that prebiotics and postbiotics have safety and standardization features that probiotics do not have. In addition they are authorized by regulatory authorities, whereas topical probiotics are not.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) aka atopic or constitutional eczema is an itchy skin disease with multifactorial etiology and a chronic-recurrent course. AD is one of the most common skin diseases with a prevalence of 2–5% of the population; the prevalence of AD has increased significantly since World War II, ranging from 10% to 20% in children and 1% to 3% in adults, although a precise estimate is rather difficult to obtain given the fluctuating course of the disease (Citation1). AD is a more frequent disease in wealthier socio-economic groups. Social class is an indicator of factors that may play a protective or facilitating role in AD, such as household size, early exposure to infection or infestation, housing conditions, level of schooling, age of the mother and mode of birth (vaginal versus cesarean section) (Citation2).

The skin of AD patients has a defective epidermal barrier associated with Th2-type inflammatory to various environmental stimuli. Often the family or personal history is positive for diseases such as allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and bronchial asthma. The cardinal symptom of AD is itching, which frequently can become so intense that it interferes with sleep and school or work activities (Citation1,Citation2).

In addition to the known genetic predisposition, other environmental factors such as exposure to food allergens, perennial and seasonal inhalants, irritants (including ‘hard’ water) and contact allergens, infections, emotional changes, and lifestyle habits such as skin hygiene patterns and frequency (such as hand washing in the recent COVID-19 pandemic) also play a role in AD (Citation3). In addition, in recent years, attention has been paid to alterations in the skin microbiota.

The management of AD is complex, as it requires short-term control of acute symptoms without compromising the overall treatment plan, which must be aimed at long-term stabilization and prevention of flare-ups. Therefore, the treatment of AD must be planned with a long-term perspective; hence the current trend is to formulate topical products with anti-inflammatory and soothing capabilities but without drugs (Citation3) so that the patients (or their caregivers) can treat the dermatitis without the fear, justified or not, of side effects.

Following the recent availability of DupilumabFootnote1 (monoclonal antibody for subcutaneous injection) for severe forms of AD (Citation4,Citation5) and pending the next oral JAK inhibitors (Citation6), topical anti-inflammatory therapy (corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors) remains the first choice for the acute phases of AD. On the other hand, the first and fundamental step in treating AD is dermocosmetic, i.e. non-aggressive daily personal hygiene combined with a supply of substances to moisturize, soothe and reconstitute the compromised skin barrier and microbiota (Citation1,Citation2). In this respect, various studies have shown that the correct use of emollients can reduce the amount of medication used (Citation7) and perhaps prevent the onset of dermatitis itself (Citation8).

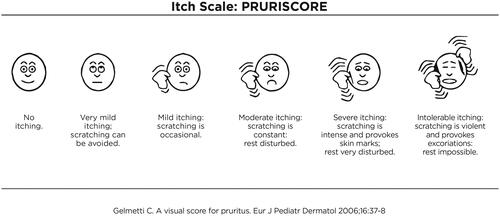

In the crowded field of new AD therapies, a prominent place must be reserved for 'biotics’ (probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics) () which are used systemically and topically in an attempt to correct the cutaneous dysbiosis present in AD, typical for the characteristic prevalence of the pathogen Staph. Aureus pathogen even in clinically normal skin. With regard to probiotics, the problems are mainly represented by the potential risk of infection in immunocompromised subjects and the possible ability of some probiotics to transmit resistance. Pre- and post-biotics, on the other hand, do not have these problems and can in fact already be marketed. The aim of the present study is: (1) to verify the efficacy and tolerability of a cosmeceutic product containing prebiotics and postbiotics in the management of mild to moderate AD, and (2) to verify the validity of PRURISCOREFootnote2 () with respect to the usual Visual Analog Scale (VAS) already present in SCORAD also in relation to the Quality of Life indexes considered in the study.

Table 1. Definitions of prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics according to present international standards.

Materials and methods

About 402 subjects, enrolled in 8 European countries, were involved in the study and followed over time for approximately 3 months. After the data-cleaning phase, 6 subjects (1.5%) were excluded from the analysis because they lacked information at baseline. The study is therefore based on a total of 396 subjects of both sexes suffering from Atopic Dermatitis defined according to Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria and recruited from the following countries indicated in who met the following inclusion criteria were studied:

Male and female sex.

Mild and/or moderate AD according to the SCORAD index (Citation9).

Patients who may use topical treatment, preferably with mometasone furoate 0.1% cream as needed.

Signature of informed consent to participate in the study.

Table 2. Individual characteristics and treatment use at baseline (t0) of the survey population.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with exudating and/or infected AD.

Patients being treated with topical and systemic immunomodulators or immunosuppressants.

Patients treated with oral antihistamines\.

Patients treated topically and/or systemically with antibiotics.

Of these 396 patients, 72 were lost to follow-up, mainly due to difficulties with the COVID-19 outbreak. Assessments were therefore performed on the 324 subjects (81.8%) who were followed up by their referring dermatologist in their respective countries of residence. In order to have a representation of AD in all age groups, the distribution was as follows: 1–3 years 12.1%; 4–15 years 35.7%; ≥ 16 years 52.2%. Patients were given the test product and a standardized cleanser by each investigator for the duration of the study. Rilastil Xerolact PbFootnote3 cream was applied to all patients on the regions affected by eczema twice daily for 15 weeks, massaging until completely absorbed. Only Rilastil Xerolact Detergent OilFootnote4 was used for cleansing, either directly on the skin with rinsing or in the bath water (possibly also as a shampoo in the case of short hair).

During the study 4 controls were carried out: t0: visit at baseline; t1: after 5 weeks from the start of treatment; t2: after 10 weeks from the start of treatment; t3: after 15 weeks from the start of treatment. The course of AD was reported in a card for each patient and monitored with: SCORAD; PRURISCORE (); clinical photo; IGA scale (Investigator’s Global Assessment) (Citation10) at t0 and at each follow-up (any adverse effects related to the application of the product to be reported as follows: 0 = absent, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe and relative measures); quality of life questionnaire according to age groups (DLQI (Citation11); CDLQI (Citation12); IDQOL (Citation13)). These indices were recorded at t0 and at each follow-up. The tolerability of the product was assessed at the end of the study and classified as: poor, moderate, good, excellent. In the questionnaire, it was also possible to add notes or observations concerning the use of the product. The patient card also recorded the number of flare-ups compared to the previous year in the same period and the opinion of the patient or caregivers on the greater significance of PRURISCORE compared to the VAS scale.

We performed descriptive analyses by tabulating frequencies and percentages (for categorical variables) and mean and median values, standard deviations (SD), quartiles and extreme values (for continuous variables). With reference to comparison between subgroups of age, categorical data were analyzed using the contingency table analysis with the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, whereas continuous data were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (as data were not normally distributed, based on the Shapiro-Wilk statistic). Comparisons between different time-points (e.g. t3 versus t0) were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data. All tests were two-sided and a p-value of less than .05 was considered as statistically significant. Data analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) statistical software.

Results

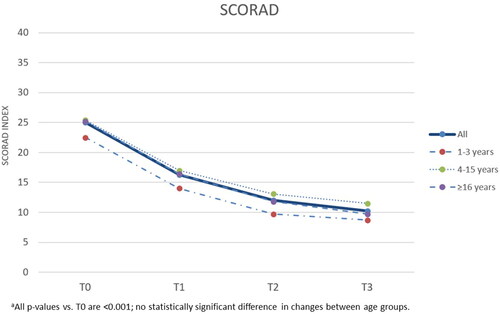

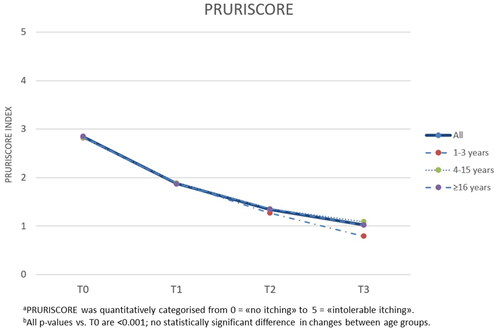

The results of the study showed that the topical product under investigation demonstrated good efficacy combined with good/very good tolerability, in all age groups. In , we report the data in all subjects at the baseline, in the data in all subjects from t0 to t3 are illustrated while and illustrate the parallel descent of the SCORAD index compared to the PRURISCORE scale (Citation14). In particular, all the average SCORAD, PRURISCORE and IGA scores decrease significantly (p < .001) over the course of the study, already after one/two months of treatment (t1 and t2) and in all the age groups considered. In summary, the Δt3–t0 of SCORAD, PRURISCORE and IGA decreased by −59.2%, −64.1% and −49.2%, respectively. The decrease in the average SCORAD and PRURISCORE scores is particularly strong in the first month of the experiment and tends to slow down slightly, but in any case does not stop decreasing, in the following 2 months. There are no significant differences in the effectiveness of the treatment between the different age groups, and in fact none of the tests comparing changes in AD severity scores between the 3 groups (infants, children, adults) was statistically significant.

Figure 2. Mean SCORAD scores of atopic dermatitis severity during the study; total and with respect to agea.

Figure 3. PRURISCORE mean scores of atopic dermatitis severity during the study, total and with respect to agea,b.

Table 3. Clinical characteristics at baseline (t0) of the investigated population.a

Table 4. Descriptive results on severity of atopic dermatitis and quality of life at different times in treated subjects.

Even with regard to the analyses on the quality of life of the patients linked to the dermatological problem, necessarily separated for the different age groups since the quality of life indices are different (IDQoL, CDLQI and DLQI), the improvements during the trial are evident and statistically significant (p < .001). The average IDQoL, CDLQI and DLQI scores decrease from initial values of around 10–12 points (depending on the indicator and the relevant age group examined) to 6–7 points at t1, to 3–4 points at t2, down to 2–2.5 points at the end of the study. Comparisons between the distributions of the scores at the start and end of the study for each dermatological quality of life index also clearly show the transition of a high proportion of patients from medium-high index scores at the start of the study – describing a moderate to strong impact on the subjects’ quality of life – to low or very low scores at the end of the study – indicating a low or no impact of atopic dermatitis on the subjects’ quality of life. Most subjects (68%) rated the tolerability of the treatment as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ and no one had to stop treatment due to intolerance. Stratifying the last information for the different age groups, this percentage at the end of the study varied between 68% for adult patients and 78% for children, with no statistically significant differences between the ages (p-value > .05).

Of note is the observation, collected at the end of the study, on the number of recurrences that occurred during the entire follow-up period. A total of 107 patients out of 241 (44.4%) with available information reported at least one (n = 53, 22.0%) or two (n = 35, 14.4%) recurrences during the study. The mean of recurrences in the whole series was 0.87 whereas the average number at baseline in the same period of the previous year was 3 recurrences. Whether we consider only those subjects who had at least one recurrence, the mean number is 1.97 recurrences. Also in this case, there are no statistically significant differences between the different age groups examined in the average number of relapses occurring during the period of the trial.

Finally, we examined two other variables collected during the study, namely the cosmetic pleasantness of the product and the individual preference between the PRURISCORE and VAS scales on which of the two most faithfully reflects the itching sensation.

On the cosmetic pleasantness of the product, more than two thirds of the respondents rated it as ‘very good’ (52%) or ‘very good’ (17%) at the end of the study, while the percentage of subjects rating the cosmetic pleasantness as ‘poor’ or ‘moderate’ was below 6% throughout the trial. Stratifying the results by age group, the results were fully comparable between the different subgroups.

At the end of the experiment, a total of 261 subjects expressed their preference between the PRURISCORE and VAS scales, answering the question as to which of the two, in their opinion, most accurately reflected the sensation of itching. The PRURISCORE was chosen by the vast majority of people (n = 212, 81.2%), while only 49 (18.8%) participants indicated a preference for the VAS scale.

Discussion

Atopic dermatitis is currently the most frequent chronic-recurrent inflammatory skin disease in the world and also one of those with the lowest quality of life due to itching and/or lack of sleep or difficulty in falling asleep. The typical course of dermatitis frequently puts the patient (and his family!) in a state of anxiety also determined by the fear that the prolonged use of drugs may have negative consequences, hence the well-known corticophobia (Citation15) and the more recent phobia toward topical calcineurin inhibitors, associated, more or less, to an aversion to substances perceived as ‘chemical’, i.e. opposite to the ‘natural’ ones. These considerations give rise to the need for products that have a curative value but are not perceived and classified as drugs.

While the attack on the immunological side of Atopic Dermatitis had a first major success with the advent of dupilumab, the attack on the dermatological side was lagging behind. On the one hand, topical crisaborole has proved relatively inefficient and not well tolerated by a not inconsiderable percentage of patients (and in any case it is a drug available in very few countries, as well as having a very high price). On the other hand, the use of probiotics on the skin is currently fraught with legal and conceptual problems (Citation16,Citation17). This obstacle has been overcome by the topical use of prebiotics and postbiotics (Citation18–20), which do not have the limitations of probiotics. In addition to classic moisturizing substances such as sodium lactate, glycerin and shea butter and anti-itch substances such as niacinamide, vitamin E and dipotassium glycyrrhizinate, the product under investigation contains a prebiotic (alpha-glucan oligosaccharide) and a postbiotic (lactobacillus ferment).

Today, a large proportion of experts believe that barrier defects play a major role not only in AD but also in the entire atopic march. It is also certain that barrier defects and immune dysregulation are often concomitant, but barrier defects seem to precede immunological abnormalities which, from this point of view, can be considered secondary phenomena. Thus, although the immune system as a whole is now the target of many innovative therapies, it can hardly be considered the target of prophylactic strategies. Unfortunately, even the use of traditional emollients (Citation21–23) as primary prophylaxis does not seem to give the hoped-for results (Citation24).

In conclusion, the trial on the treatment with the product (Rilastil Xerolact PB) conducted on about 400 subjects suffering from AD followed over time for 3 months, shows the good efficacy of the product for all the measures of severity of AD examined, i.e. SCORAD, PRURISCORE and IGA, already after only one month of treatment. The improvement in average severity scores also continued in the following two months until the end of the study. Treatment with Rilastil Xerolact PB is effective in reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis in all 3 age subgroups examined, i.e. in infants, children and adults, without significant differences between the different age groups. The response to this treatment can be illustrated in .

Figure 5. This very pruritic dermatitis of the antecubital fossa was rapidly contained by the treatment.

Figure 6. This chronic perioral dermatitis in this young boy was finally controlled by the treatment.

No less important is the data on rescue therapy with topical corticosteroids which, from an average of 3 episodes in the often period of the previous year, falls to 0.87 during treatment with Rilastil Xerolact PB.

In parallel with the disease severity scores, the dermatological quality of life indexes also improved in a clear and statistically significant manner in all age subgroups. Again, improvements are clear after one month of treatment and continue throughout the follow-up period. At the end of the study, more than 80% of patients in each age group investigated reported low or very low quality of life scores, indicating that the impact of AD on the quality of life of patients following quarterly treatment with Rilastil Xerolact PB is null or very limited.

The tolerability and safety of the treatment appeared to be reassuring. A small number of patients reported adverse effects – mostly mild, such as redness, tingling, and minor irritation – and less than 3% of patients discontinued treatment throughout the 3-month follow-up period due to adverse events.

The tolerability of the treatment was rated as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ by about two-thirds of the patients and ‘poor’ by almost none. Cosmetic pleasantness was also rated as ‘very good’ or 'excellent’ by more than two-thirds of the patients. This finding is of relevance as it expresses good patient compliance, which may result in patients being more motivated to continue treatment even in disease remission phases.

Finally, the vast majority of participants, more than 80%, indicated that they preferred the use of the PRURISCORE score over the VAS scale to express more faithfully the degree of itching perceived during the study. The study’s limitation in terms of the efficacy of this topical treatment lies in the lack of a control group. In addition, we agree that the precise role of prebiotics and postbiotics (Citation25,Citation26) was not formally demonstrated in this study since these substances were part of a more complex formulation; on the other hand, it can be reasonably stated that prebiotics and postbiotics have safety and standardization features that probiotics do not have.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Carlotta Galeone and Dr Claudio Pelucchi of Statinfo® company ([email protected]) for their kind support and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Dupilumab is the first biological drug approved for the treatment of adults and children >6 years old with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis that is not adequately controlled with topical treatments or when these treatments are not indicated. Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the activity of IL-4 and IL-3, two cytokines that act as mediators of chronic Th2 inflammation characteristic of AD.

2 PRURISCORE is an itch assessment score, developed in 2006 by the lead author of this study, to overcome the limitations of the classic VAS system in use in SCORAD. The PRURISCORE is inspired by the pain scale of Wong and Backer and, according to the author, is more suitable to capture the intensity of a subjective symptom through a combination of pictograms and short descriptions of the same (see ).

3 Rilastil Xerolact PB Balsam is a product designed for the basic emollient treatment of AD, formulated with a prebiotic (alpha-glucan oligosaccharide) and a postbiotic (Lactobacillus ferment). These substances act in synergy with a moisturizing–relipidizing complex (sodium lactate, glycerine, shea butter) and an anti-itch complex (niacinamide 4%, vitamin E, dipotassium glycyrrhizinate). Lactobacillus ferment is composed of concentrated metabolites (oligopeptides, fatty acids and glycolipids) from bacterial fermentation of lactobacilli to protect the skin and its microbiota. There are no live microorganisms or residual bacterial fragments in the extract, thanks to an exclusive, patented extraction method (‘PBTech’ method) of the latest generation, the main innovation of which is that it is possible to generate these substances in the absence of a culture medium and thus obtain only the desired substances in pure form and without catabolites, bacterial fragments or whole contaminating cells, thus achieving a high degree of safety.

RILASTIL XEROLACT PB balm has the following INCI: Aqua (Water) • Triethylhexanoin • Glycerin • Polyglyceryl-3 Distearate • Butyrospermum parkii (Shea) Butter • Niacinamide • Methylpropanediol • C15-19 Alkane • Glyceryl Stearate • Sodium Lactate • Alpha-Glucan Oligosaccharide • Behenyl Alcohol • Glyceryl Stearate Citrate • Dipotassium Glycyrrhizate • Tocopheryl Acetate • Lactobacillus ferment • Schisandra chinensis Fruit Extract • Xanthan Gum • Mannitol • Lactic Acid • Chlorphenesin • o-Cymen-5-ol • Tetrasodium Glutamate Diacetate • Sodium Hydroxide • Parfum (Fragrance).

4 RILASTIL XEROLACT OLIO DETERGENTE has the following INCI: Aqua (Water) • Glycerin • PEG-7 Glyceryl Cocoate • Sodium Cocoamphoacetate • Sodium Lactate • Sodium Lauryl Glucose Carboxylate • PEG-90 Glyceryl Isostearate • Propanediol • Polysorbate 20 • Lauryl Glucoside • Sodium Chloride • Lactic Acid • Coco-Glucoside • Glyceryl Oleate • Oryza sativa (Rice) Bran Oil • Prunus amygdalus dulcis (Sweet Almond) Oil • Niacinamide • Schisandra chinensis Fruit Extract • Laureth-2 • Sodium Citrate • Caprylhydroxamic Acid • Citric Acid • Sorbic Acid • Tocopherol • Hydrogenated Palm Glycerides Citrate • Lecithin • Ascorbyl Palmitate • Parfum (Fragrance).

References

- David Boothe W, Tarbox JA, Tarbox MB. Atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:21–37.

- Ständer S. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1136–1143.

- Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(12):adv00161.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Deleuran M, et al. Dupilumab provides favorable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 3 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(4):567–577.

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–1293.

- Fishbein AB, Silverberg JI, Wilson EJ, et al. Update on atopic dermatitis: diagnosis, severity assessment, and treatment selection. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):91–101.

- Grimalt R, Mengeaud V, Cambazard F. Study investigators’ group. The steroid-sparing effect of an emollient therapy in infants with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled study. Dermatology. 2007;214(1):61–67.

- Czarnowicki T, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Novel concepts of prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis through barrier and immune manipulations with implications for the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1723–1734.

- AA.VV. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus report of the European task force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186(1):23–31.

- Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, et al. The 5-point investigator’s global assessment (IGA) scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatol Treat. 2015;26(1):23–31.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The children’s dermatology life quality index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942–949.

- Basra MK, Gada V, Ungaro S, et al. Infants’ dermatitis quality of life index: a decade of experience of validation and clinical application. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(4):760–768.

- Williams HC, Chalmers J. Prevention of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(12):adv00166.

- Giua C, Floris NP, Schlich M, et al. Dermatitis in community pharmacies: a survey on Italian pharmacists’ management and implications on corticophobia. PHAR. 2021;68(3):671–677.

- Trikamjee T, Comberiati P, D’Auria E, et al. Nutritional factors in the prevention of atopic dermatitis in children. Front Pediatr. 2021;8:577413.

- Jeong K, Kim M, Jeon SA, et al. Randomized trial of Lactobacillus rhamnosus IDCC 3201 tyndallizate (RHT3201) for treating atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(7):783–792.

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al. Expert consensus document: the international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(8):491–502.

- Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104 (Suppl 2):S1–S63.

- Salminen S, Collado MC, Endo A, et al. The international scientific association of probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(9):649–667.

- Tiplica GS, Kaszuba A, Malinauskienė L, et al. Prevention of flares in children with atopic dermatitis with regular use of an emollient containing glycerol and paraffin: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(3):282–289.

- Lowe AJ, Su JC, Allen KJ, et al. A randomized trial of a barrier lipid replacement strategy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis and allergic sensitization: the PEBBLES pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):e19–e21.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Christensen R, et al. Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2):CD012119.

- Skjerven HO, Rehbinder EM, Vettukattil R, et al. Emollient and early complementary feeding to prevent infant atopic dermatitis (PreventADALL): a factorial, multicentre, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):951–961.

- Fanfaret IS, Boda D, Ion LM, et al. Probiotics and prebiotics in atopic dermatitis: pros and cons (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(6):1376.

- Baldwin H, Aguh C, Andriessen A, et al. Atopic dermatitis and the role of the skin microbiome in choosing prevention, treatment, and maintenance options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(10):935–940.