Abstract

Objectives

To describe the results of a structured literature review of real-world outcomes with ixekizumab in patients with psoriasis (PsO) and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Methods

Literature databases, conference proceedings and additional sources were searched for relevant publications. Real-world studies of ≥25 ixekizumab-treated patients with PsO and/or PsA were included. Data on clinical effectiveness, treatment persistence/patterns, economic outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and safety were extracted.

Results

Fifty-one publications were included. Most studies focused on patients with PsO, and the number of publications with a focus on PROs was low. Studies of treatment patterns found that in general, ixekizumab had similar or better persistence versus other biologics, and rates or risk of switching similar to or less than comparator drugs. Adherence to ixekizumab was high, and patients were less likely to discontinue ixekizumab than other biologics. Ixekizumab was effective in the real world, with a safety profile consistent with that reported in clinical trials.

Conclusions

Real-world use of ixekizumab in PsO and PsA is effective and safe, with generally high treatment persistence and adherence. Further work is required to determine the impact of ixekizumab on PROs in PsO, and to gather more data on real-world use of ixekizumab in PsA.

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease characterized by a relapsing/remitting disease course and erythematous, itchy demarcated plaques (Citation1–4), which imposes a significant burden on patients, particularly in those with moderate-to-severe disease. Approximately 20–30% of patients with PsO also have psoriatic arthritis (PsA), an inflammatory musculoskeletal disease associated with progressive joint disease and impaired physical functioning (Citation5–8). The burden associated with PsO and PsA is reflected in poor quality of life (QoL), psychological distress, anxiety and depression, financial burdens and absences from work (Citation5,Citation7,Citation9–12).

Current therapies for PsO and PsA include biologics targeting the inflammatory cascade. One of these targeted therapies, the anti-interleukin-17A (anti-IL-17A) antibody ixekizumab, reduces the signs and symptoms of these diseases, with an established safety profile. In randomized controlled trials, ixekizumab showed greater efficacy than etanercept (UNCOVER) (Citation13–15), superior efficacy to guselkumab at 12 (but not 24) weeks (IXORA-R) (Citation16,Citation17) and superior efficacy to ustekinumab up to 52 weeks (IXORA-S) (Citation18,Citation19) in improving the signs and symptoms of PsO. In the SPIRIT trials, ixekizumab was effective in the treatment of active PsA (Citation20–22), and resulted in significantly greater simultaneous improvement of joint and skin symptoms compared with adalimumab at 24 weeks, with these improvements maintained at 52 weeks in biologic-naïve patients (Citation22–24).

Real-world evidence has become increasingly important in healthcare decision making (Citation25–28). Such data complement clinical trial data and allow expansion of the knowledge base for the drugs in question into a broader patient population than that included in clinical trials. The real-world population may be older or younger than the population studied in clinical trials, with comorbidities or a treatment history that may have precluded them from clinical trial participation (Citation29). Ixekizumab has been available for the treatment of moderate-to-severe PsO and active PsA since 2016 and 2017, respectively, in the US (Citation30) and subsequently in other territories including the European Union (Citation31); therefore, it was of interest to determine the performance of ixekizumab in the real-world setting. Drug persistence is an important indicator of treatment success in real-world settings, as it can be interpreted as providing additional information on the efficacy and safety of a drug, as well as patient satisfaction with the treatment (Citation32,Citation33).

In this paper, we describe the results of a structured literature review that aimed to present an overview of real-world outcomes including but not restricted to clinical effectiveness, treatment persistence and other treatment patterns, economic outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and safety, associated with the use of ixekizumab in PsO and PsA in the real-world setting.

Patients and methods

This structured literature review used validated methodologies consistent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Citation34) and the Cochrane Collaboration (Citation35). The literature search was performed by researchers from Adelphi Values Limited.

Published literature search

The search of published literature was conducted on 7 April 2021, using Embase, Medline®, Econlit® and EBM Reviews® databases and disease- and drug-related keywords (Supplementary Table 1). Since ixekizumab was launched in 2016, the search included a 5-year time horizon from 1 January 2016 to 6 April 2021. Additional limits included English language and human studies only. Medline® searches included Epubs ahead of print, in-process and other non-indexed citations, and Medline® Daily and Versions® 1946 to present. The EMB Reviews database included the following: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database; and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database.

Conference proceedings and grey literature search

A number of global, national and regional conference proceedings from 2019 to 2021 were searched for relevant abstracts (Supplementary Table 2). Additional papers were sourced from the reference lists of relevant reviews and HTA reports identified in the literature search, and from internal Eli Lilly databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Article eligibility criteria were based on the patients, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study design (PICOS) framework. Eligibility criteria are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, included studies were those with populations of ≥25 ixekizumab-treated patients with PsO and/or PsA, which were investigating outcomes related to clinical effectiveness, safety, economics, PROs and/or treatment patterns and had the following real-world study designs: clinical observational studies; longitudinal, cross-sectional or cohort studies; pragmatic studies; claims studies; medical records, or database/registry studies; and pharmacoeconomic studies. Full publications, conference abstracts/posters and letters to the editor that described results of real-world studies were included. No geographic restriction was placed on the studies.

Excluded were clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, case reports or case studies, reviews (including systematic reviews), comments, editorials and conference abstracts/posters that clearly presented data from a published paper.

Selection process

Once the searches were complete, an abstract screening was performed by one researcher, with any discrepancies resolved by a second researcher. Article abstracts that could not be excluded in the abstract screening phase were retained for full-text screening; for ambiguous conference abstracts, an attempt to source the posters was made.

In the full-text screening phase, full publications were screened by researchers using the PICOS-based inclusion and exclusion criteria, with eligibility disputes resolved by a senior researcher.

Data extraction

Data from the included articles and abstracts were extracted into an Excel sheet by an experienced researcher and quality checked by a senior researcher. Variables extracted included: publication information and study identification features; study design and duration; characteristics of the study population, including whether patients had PsO and/or PsA; dose, frequency of administration and duration of ixekizumab treatment; statistical methods; outcomes data; and key conclusions.

Results

Study selection

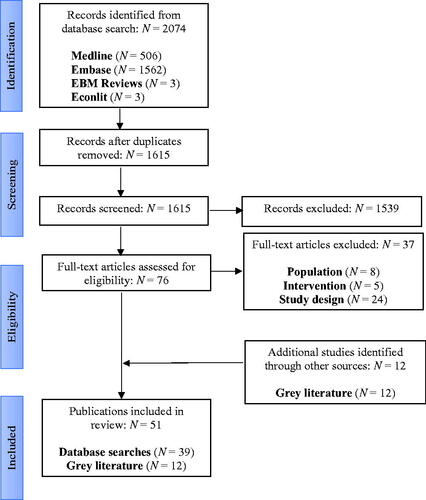

The total number of hits retrieved from the published literature search was 2074 (). Once duplicates were removed, 1615 were taken to title and abstract screening, and of these, 76 were retained for full-text screening. Following full-text screening, 37 articles were excluded: 8 due to the included population, 5 due to the intervention, and 24 due to the study design. A total of 39 full-text records were retained. A total of 12 studies were identified for inclusion in the conference proceedings and grey literature search, giving a total of 51 included publications.

The majority (N = 48) of included publications were in patients with PsO, with only three having a PsA focus. Publication types were conference abstracts (PsO: 16; PsA: 2), full papers (PsO: 23; PsA: 0), letters to the editor describing real-world study results (PsO: 4; PsA: 1) and e-posters (PsO: 5; PsA: 0). Three of the publications described various results from the same cohort of patients participating in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry (Citation36–38), so the 51 publications described 49 unique studies.

Most studies were from North America (17 US; 4 Canada; 2 US and Canada), followed by Spain (N = 8) and Italy (N = 6). Two global studies were included, as were two each from Israel and the United Kingdom/Ireland and one each from France, Austria, Slovenia, Sweden, Denmark and Japan.

Study characteristics and treatments

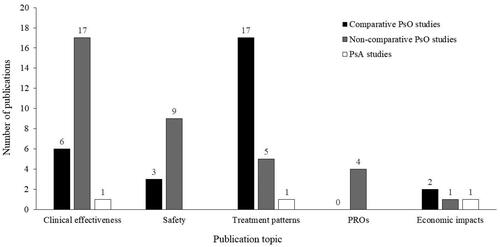

Of the 25 comparative PsO studies (Supplementary Table 3; n≈109,000 across all studies), the majority focused on treatment patterns, including persistence (Citation39–55), followed by clinical effectiveness outcomes (Citation53,Citation56–60), safety (Citation57–59,Citation61), and economic impacts (Citation62,Citation63) (). The comparative studies often included more than one outcome focus (Supplementary Table 3). Timepoints for outcomes included 4 weeks (Citation50,Citation64–66), and 12, 24 and 52 weeks (Citation53,Citation56–60,Citation67). Where reported, follow-up ranged from 20 weeks to 3 years.

Figure 2. Topics covered by the included papers. Individual studies could include more than one topic. PROs, patient-reported outcomes; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: psoriasis.

Generally, the comparators investigated were other biologics, with most studies comparing between treatment groups, but some studies comparing results with previous treatment (Citation53,Citation61,Citation68). One of the PsO studies was designed to compare the use of ixekizumab with regard to clinical effectiveness, safety and PROs in the real-world setting with the results of the UNCOVER clinical trials (Citation69).

A total of 26 publications were non-comparative studies investigating ixekizumab only (Supplementary Table 4; n = 4660 across all studies), with the three included PsA studies all being non-comparative. The majority of non-comparative PsO publications focused on clinical effectiveness (Citation37,Citation38,Citation61,Citation64,Citation66–79), followed by safety outcomes (Citation61,Citation69–73,Citation78–80), treatment patterns, including persistence (Citation61,Citation67,Citation75,Citation77,Citation81,Citation82), PROs (Citation36,Citation64,Citation66,Citation69), and economic impact (Citation83) (). Studies often included more than one focus, for example, clinical effectiveness and PROs or treatment patterns (Supplementary Table 4). Timepoints for outcomes included 1, 3, 6 and 12 months (Citation61,Citation68–73,Citation75,Citation77,Citation78). Where reported, follow-up ranged from up to 6 months to 2 years.

The three non-comparative PsA studies (n = 522 across all studies) investigated clinical effectiveness, treatment patterns and economic impacts (each N = 1). Timepoints for outcome assessment were 24 and 48 weeks (Citation84–86) and where reported, follow-up was 12 months.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics in comparative ixekizumab studies were generally balanced across groups (Supplementary Table 3). Where reported, mean age in the ixekizumab and comparator groups was 45.0–53.6 and 41.3–60.2 years, respectively. Where only the overall age of the entire study population was reported, mean age was 42.1–54.2 years. The percentage of patients with coexisting PsA in the comparative ixekizumab studies was 12.0–43.0% with ixekizumab, where reported, and 0–45.7% with comparators. An overall percentage for the entire study population was only reported in two studies; this was 50.7% and 65.2% (Supplementary Table 3). The proportions of biologic-experienced patients, where reported, ranged from 0% to 100% in ixekizumab groups versus 0–98.3% in comparator groups. Where only the overall percentage for the entire study population was reported, it ranged from 0% to 100%.

In the studies of ixekizumab alone in patients with PsO, mean age was 44.0–57.9 years, the percentage of patients with coexisting PsA was 15–71%, and the proportion of patients who were biologic-experienced was 5–100%, where reported (Supplementary Table 4).

Treatment persistence

There are two main sources of real-world persistence data: medical insurance claim databases; and cohorts/registries.

Claim databases

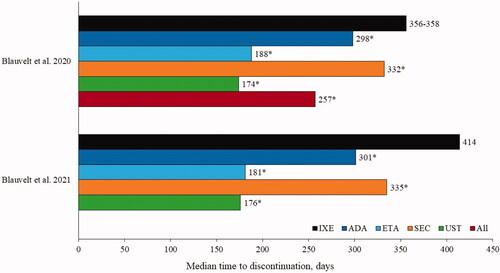

Several US-based studies from Blauvelt and colleagues have investigated the persistence of ixekizumab versus various biologics. Persistence was defined as continuous drug claims over time, allowing for a gap of <60 days (Citation44) or ≤60 days (Citation40) between the last day of drug supply and date of the next refill. Ixekizumab had a significantly (p < .001) longer median time to discontinuation versus comparator biologics in two studies (Citation40,Citation44) ().

Figure 3. Median time to discontinuation for ixekizumab versus comparators in Blauvelt et al. 2020 (Citation1) and Blauvelt et al. 2021 (Citation2). *p < .001 vs IXE. ADA: adalimumab; All: all comparators; ETA: etanercept; IXE: ixekizumab; SEC: secukinumab; UST: ustekinumab.

Additional studies from this research group defining persistence as a gap of <60 days found that, compared with adalimumab recipients, patients treated with ixekizumab had a significantly higher persistence rate (54.5% vs 42.2%; p < .001) and a significantly higher probability of persistence (p = .004) (Citation42). Similarly, the probability of persistence was significantly greater with ixekizumab versus secukinumab (p = .007) (Citation41). In biologic-experienced patients, 44.9% versus 36.9% of those receiving ixekizumab and secukinumab, respectively, remained persistent over 18 months of treatment (p = .007) (Citation43).

Discrepancies in persistence data may be explained by varying definitions of non-persistence and of the gap between refills considered permissible. A comparative study assessing the persistence of adalimumab, apremilast, etanercept, ixekizumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab in patients with plaque PsO used three definitions of a permissible gap: 150 days for ustekinumab and 90 days for other drugs; 120 days for all drugs; and a 2-day supply for all drugs (Citation48). Ustekinumab was the most sensitive to changes in the permissible gap definition, with median persistence of 358 days and 189 days depending on the definition used. In the scenario where ustekinumab persistence was 189 days (2-day supply), median persistence for ixekizumab and secukinumab was 252 and 222 days, respectively (Citation48).

A study that utilized data from 1562 patients included in the IQVIA LifelinkTM Treatment Dynamics database, which consists of a panel of 21,769 pharmacies in France, defined treatment discontinuation as a gap of ≥90 days after the expected treatment renewal date. Patients treated with ustekinumab (28% of patients) had the highest 1-year persistence rate (63.9%) compared with ixekizumab (6% of patients; 58.5%), secukinumab (26% of patients; 57.0%), adalimumab (33% of patients; 47.9%) and etanercept (7% of patients; 29.3%), suggesting that newer biologics such as the anti-ILs may have higher persistence than the older anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents (Citation49).

Cohort/registry studies

Results from cohort and registry studies also suggest that the persistence of ixekizumab is generally similar to or longer than persistence with other biologic therapies. A study using data from the Swedish National Patient Register (N = 2258) found that persistence was highest after 1 year of treatment in patients treated with ixekizumab (81.3%), ustekinumab (79.9%) and secukinumab (75.9%), compared with adalimumab (64.6%) and etanercept (57.8%) (Citation54).

However, persistence of the anti-IL-12/23 ustekinumab was significantly higher (p < .001) than the comparator anti-IL-17As (ixekizumab and secukinumab), anti-TNFs (adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab), and apremilast (phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor) in patients enrolled in the Slovenian Psonet Registry, with biologic treatment discontinuation defined as a gap in treatment of >12 months (Citation52). Ixekizumab and secukinumab had similar persistence rates in both biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients; however, no adjustments for differences in baseline characteristics and the duration of the observation period were made, and the number of treatment cycles analyzed was greater for ustekinumab (N = 613) and adalimumab (N = 831) versus ixekizumab (N = 98) and apremilast (N = 94).

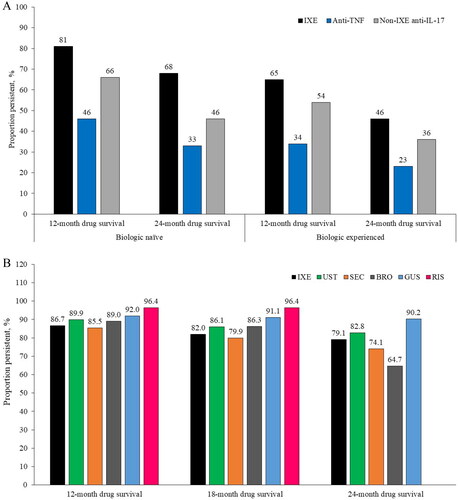

A study including patients enrolled in the North American Corrona Registry showed that ixekizumab demonstrated increased persistence, defined as a medication gap of ≤60 days, at 12 and 24 months versus anti-TNFs and other anti-IL-17As in biologic-naïve patients and in biologic-experienced patients (). No adjustment for baseline characteristics or observation period was made (Citation51). A retrospective study in a tertiary medical center in Israel found that anti-IL-17A-naïve patients had greater ixekizumab persistence than patients with prior anti-IL-17A exposure, likely due to increased efficacy in naïve versus experienced patients (Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 90 at 12 weeks: 71.4% vs 43.8%; p = .055) (Citation53).

Figure 4. Persistence rates of ixekizumab versus comparators in (A) the Corrona Registry (Citation3); and (B) a retrospective study conducted by Torres and colleagues (Citation4). BRO: brodalumab; GUS: guselkumab; IL: interleukin; IXE: ixekizumab; RIS: risankizumab; SEC: secukinumab; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; UST: ustekinumab.

Torres and colleagues conducted a retrospective study in Europe and North America that included data from patients treated with anti-IL-23s (risankizumab and guselkumab) in addition to other biologic classes (Citation55). Persistence was defined as the time from initiation to definitive discontinuation of treatment or last clinical observation. At 12, 18 and 24 months, numerically higher persistence rates were reported for the anti-IL-23 drugs (). No adjustment for baseline characteristics or observation period was made.

Data from the Austrian Psoriasis Registry (PsoRA) was used in a persistence study where treatment discontinuation was defined as a treatment interruption of >12 weeks, or 24 weeks for ustekinumab (Citation47). The analysis showed that at 12 months of follow-up, the unadjusted persistence rate was 89% for ustekinumab, 86% for ixekizumab, 78% for secukinumab, 76% for adalimumab and 66% for etanercept (all p < .04 vs ixekizumab). After adjusting for the observation period, no statistically significant differences were found between ustekinumab and ixekizumab (p = .075). Similarly, after adjusting for biologic-naïve status, persistence rates were similar between ixekizumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab, all of which were superior to TNF inhibitors at 12 months.

Clinical effectiveness

In the comparative studies (), the proportions of patients with PsO achieving PASI75, PASI90 and/or PASI100 with ixekizumab were similar to or better than with comparative biologics in the majority of studies. In an Italian study conducted in two centers, ixekizumab and secukinumab were both highly effective in the treatment of patients with PsO (19.2% with coexisting PsA) in a direct comparison but secukinumab had a faster onset of action, with significantly (p < .001) higher PASI responses than those seen with ixekizumab at 12 weeks; at 24 weeks PASI responses between the two drugs were similar (Citation56). A larger Austrian study conducted at 26 centers found that ixekizumab was superior to other biologic treatments (including secukinumab, ustekinumab and anti-TNFs) with respect to PASI improvement from baseline to 3 months, and had the highest long-term PASI improvement (to 24 months) (Citation47).

Table 1. Comparative studies reporting PASI75/90/100 for ixekizumab in patients with psoriasis.

Results also suggest that being biologic-naïve may be associated with a good response to ixekizumab; a study that stratified patients by previous anti-IL-17A exposure found higher PASI responses in those who were anti-IL-17A-naïve (), but these results were not statistically significant (Citation53). Similarly, a retrospective, non-comparative, cohort study in Spain that included 68.5% biologic-experienced patients with PsO (15.3% with coexisting PsA) found that PASI90 response at both 3 and 12 months was associated with no prior biologic therapy (3 months, p = .007; 12 months, p < .001) (Citation78). Achievement of PASI <2 at 12 months was also associated with no prior biologic therapy (p < .001). Patients with PsO (60% with coexisting PsA) who had a history of fewer failed biologics (0–1) were more likely to achieve PASI100 than those who had a history of ≥2 failed biologics (83% vs 60%) in a Canadian study (Citation75). Further evidence to support this includes two Spanish studies; in one, patients who were biologic-naïve had a significantly higher PASI75 response rate at Weeks 12–16 versus biologic-experienced patients (p = .037) (Citation72), and in the other, PASI75 and PASI90 responses at Week 16 and 52 were better in biologic-naïve patients (Citation77). Additionally, an Italian study reported that being biologic-naïve was the only variable associated with a reduced absolute PASI score (p < .05) (Citation71).

Non-comparative PsO studies summarized in (Citation70–73,Citation75,Citation77–79) show that ixekizumab is effective in the real-world setting, with most studies reporting that at 12, 24 and 52 weeks, >70% of patients achieved a PASI75, ≥50% of patients achieved a PASI90 and ≥38% achieved a PASI100.

Table 2. Non-comparative studies reporting PASI75/90/100 for ixekizumab.

Of note are results for ixekizumab in an Italian study (Citation69) which examined real-world data obtained in the clinic side by side against those from randomized controlled trials, although no direct comparisons were made. Ixekizumab performed better with regard to PASI90 and PASI100 responses than in the randomized UNCOVER-3 trial at 12 weeks, and similarly to UNCOVER-3 at 20 weeks.

Several studies found clinical response following a switch to ixekizumab after secukinumab failure. An Italian study in patients with PsO (29% with coexisting PsA) demonstrated strong responses to ixekizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks in PASI75 (∼80%) and PASI90 (∼70%), with PASI100 responses being ∼39% (Citation68). Another study demonstrated similar results for ixekizumab (PASI75, 90 and 100 at 12 and 24 weeks: 76.5% and 73.3%, 52.9% and 53.3% and 29.4% and 33.3%) (Citation67).

An analysis that stratified patients according to PASI at baseline (<12 vs ≥12) and weight (<100 kg vs ≥100 kg) found that patients with more severe disease tended to have a greater absolute improvement in clinical outcomes than those with less severe disease, while there was no impact on weight (Citation37).

In the one non-comparative study in patients with PsA that reported PASI results, more than 80% of patients receiving ixekizumab achieved PASI75 and PASI90 at Week 24, while more than 50% achieved PASI100; at Week 48, PASI75 response was maintained () (Citation84).

Safety

Overall, there were no unexpected safety signals reported in ixekizumab-treated patients in the real-world studies. Common adverse events in studies included injection site reaction/erythema/pain (occurring in 2.2–36.8% of patients) (Citation57,Citation70–73,Citation78), infections (0.4–15.1%), including candida (8.0–13.8%) (Citation57–59,Citation78–80), respiratory infections (1.7–13.8%) (Citation57–59,Citation69) and dermatitis/eczema (1% and 5%) (Citation71,Citation73). Discontinuations due to adverse events were infrequent (0–5%) (Citation57,Citation70,Citation72,Citation73,Citation78).

PROs

Overall, few studies reported on PROs. While one comparative study of patients with PsO provided baseline Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) results, it did not assess changes in these outcomes with treatment (Citation51).

Three non-comparative studies in patients with PsO (proportion of patients with coexisting PsA not stated) found an improvement in QoL with ixekizumab treatment using the DLQI questionnaire (Citation36,Citation37,Citation64,Citation66). In one study of 114 patients with PsO, a DLQI score of 0 or 1 was seen in 19% of patients at baseline, and in 57%, 68% and 67% of patients at 1, 3 and 12 months (Citation64). In a second study (N = 154), 70% of patients with a static physician global assessment (sPGA) of 0 or 1 at 1 month also had a DLQI score of 0 or 1; in those who did not have an sPGA score of 0 or 1 at 1 month, 54% had a DLQI score of 0 or 1 at 3 months (Citation66). The third study in 136 patients with PsO (proportion of patients with coexisting PsA not stated) reported that 90% of patients treated with ixekizumab who had a DLQI score of ≤5 at enrollment maintained or improved at follow up, while 70% and 71% of patients with DLQI >5 or DLQI >10 at enrollment improved to DLQI ≤5 and DLQI ≤10, respectively (Citation36). This study also demonstrated a reduction in the work-related burden associated with PsO, measured using the WPAI scale; after 6 months’ treatment with ixekizumab, patients reported improvements in the number of work hours missed (by 1.6%), working impairment (by 10.3%), overall number of work hours affected (by 10.6%) and impairment of daily activities (by 13.4%) (Citation37). When patients were stratified by disease severity at baseline (PASI <12 vs ≥12) and weight (<100 kg vs ≥100 kg), change in WPAI domains was greater in patients with more severe versus less severe disease, and was modestly greater in patients <100 kg (Citation37). No study of patients with PsA reported on these outcomes.

Treatment patterns

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence in patients with PsO receiving ixekizumab in the real world is high compared with other biologics. A study comparing ixekizumab versus a pooled set of other biologics (adalimumab, etanercept, secukinumab and ustekinumab) over 1 – 3 years found that patients on ixekizumab had the highest proportion of days covered (PDC: 0.532 vs 0.457, p ˂ .001) and had a higher rate of monotherapy (monotherapy PDC: 0.527 vs 0.448, p ˂ .001) up to 3 years (Citation44). Similarly, adherence with ixekizumab versus guselkumab was higher in a 1-year study (234.3 vs 219.1 days; PDC: 0.64 vs 0.60; p = .001) (Citation39), and ixekizumab recipients had a higher likelihood of adherence compared with secukinumab (hazard ratio (HR) 1.31; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–1.60) based on odds of high persistence (Citation41). Another study reported adherence rates at 12 months of 54.1% for ixekizumab, 46.5% for secukinumab, 41.8% for adalimumab, 30.1% for ustekinumab, 33.6% for etanercept and 34.0% for apremilast (Citation46).

Treatment switching

Treatment switching in patients with PsO receiving ixekizumab was less common than or similar to switching rates seen with other biologics (Citation42,Citation43). In one study of ixekizumab versus secukinumab that analyzed records from 1 March 2016 to 31 October 2019, there was a lower rate of switching in ixekizumab versus secukinumab recipients (26.6% vs 34.0%; p = .009) (Citation43), while in a second study that analyzed records from 1 March 2016 to 31 May 2018, the risk of switching was numerically lower with ixekizumab than with secukinumab, but not statistically significant (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.70–1.11); in this study, those receiving ixekizumab had a lower risk of discontinuation than those receiving secukinumab (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.70–0.96) (Citation41). A similar study found a lower risk of switching and discontinuation with ixekizumab compared with adalimumab (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.57–0.91 and HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.62–0.88, respectively) (Citation42). Consistent with these results, a final database study comparing treatment patterns for ixekizumab at 12 months and secukinumab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, etanercept and apremilast at 12, 18 and 24 months found that patients receiving ixekizumab or ustekinumab were the least likely to switch treatments at all timepoints (Citation46).

Data from the Austrian PsO Registry of patients treated with biologics between 1 January 2015 and 30 November 2019 showed a substantial number of intra-class switches, particularly switches from secukinumab to ixekizumab (41.1%; only 6.9% switched from ixekizumab to secukinumab). In addition, 19% of patients stopped and then restarted ixekizumab, responding to the therapy after the restart (Citation47).

A study of the use of concomitant medications in patients (N = 1316) with PsO receiving ixekizumab demonstrated a significant reduction in the use of corticosteroids, non-steroidal topical treatments, non-biologic systemic treatments and phototherapy when patients were switched to ixekizumab from their previous medications (all p ≤ .015) (Citation82).

Reasons for treatment discontinuation

Common reasons for the discontinuation of ixekizumab in comparative studies included loss of effectiveness/secondary failure (Citation47,Citation53). A study of anti-IL-17As found that the main reasons for discontinuation overall were primary failure, loss of efficacy and side effects; in the discontinued treatment cycles in this study, the main reason for discontinuation for all treatments was no or partial remission (30% of cases) (Citation47). Only 20% of the ixekizumab discontinuations were due to no or partial remission (Citation47). Loss of efficacy was the reason in 31% of adalimumab discontinuations compared with 23% of ixekizumab discontinuations (Citation47). Discontinuations for adverse events were more frequently reported for ixekizumab (29%) than the other biologics (11.6–18.8%) (Citation47). When all treatment cycles in this study were considered, loss of effectiveness was still the main reason for discontinuation of adalimumab (12.9% vs 3.9% of ixekizumab cycles) (Citation47). The main reason for discontinuation of etanercept, secukinumab and ustekinumab was no remission or partial remission, while the main reason for discontinuation of ixekizumab was still adverse events, but the percentage of discontinued cycles was comparable to that of other agents (4.9% vs 6.5%, 5.2%, 6.9% and 3.5% for adalimumab, etanercept, secukinumab and ustekinumab, respectively) (Citation47).

Common reasons for discontinuation in non-comparative PsO studies were similar: primary failure, secondary failure and adverse events (Citation75,Citation77).

Economic burden

A Spanish cost-effectiveness study of real-life data calculated the average direct costs (list price) per PASI100 responder and found that, overall, anti-IL-17As had lower direct costs compared with anti-TNF and an anti-IL-12/23 (Citation62). Etanercept was the most expensive at 526,800 euros, while ixekizumab and brodalumab were the least expensive, at 68,467 and 62,165 euros, respectively. Sensitivity analysis showed that to reach similar levels of cost-effectiveness as brodalumab and ixekizumab, substantial discounts (50–90%) were required for etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab and infliximab.

Economic studies demonstrate that direct drug-related cost is the major contributor to the costs of treatment in PsO patients receiving ixekizumab in the US. Drug costs were the primary driver of total all-cause costs in one non-comparative US study; the mean total cost per patient per month was US$8,371 for the first 3 months of treatment, of which pharmacy costs were US$7,792; ixekizumab pharmacy costs were US$7,079, with US$713 for other pharmacy costs. Only 4% of the costs were covered by patients, with US$6,810 (96.2%) covered by health plans (Citation83). Another US analysis found that the greater number of ixekizumab induction doses required in the first year of treatment resulted in higher all-cause healthcare costs per patient per month in ixekizumab-treated patients than secukinumab-treated (US$836 higher) or adalimumab-treated patients (US$977 higher) (Citation63).

Discussion

This structured literature review identified 51 publications describing the use of ixekizumab in PsO and, to a certain extent, PsA in the real-world setting. These mostly consisted of conference abstracts and posters, followed by fully published papers, with 26 focusing on ixekizumab alone, and 25 comparative studies of various biologics used in the treatment of PsO and PsA. Studies of patients with PsO dominated, likely due to the more recent approval of ixekizumab for PsA (Citation30,Citation31).

Of the publications included in this review, the largest number focused on treatment patterns. Interestingly, studies that investigated ixekizumab and other anti-ILs in addition to anti-TNFs generally concluded that as a group the newer anti-ILs may have higher persistence than anti-TNFs (Citation49,Citation54). The main data sources for treatment persistence in this review were claims databases and cohort/registry studies. Limitations of these kinds of studies include the potential for mis-coding, misclassification, missing codes and no clinical data. In addition, the claims database studies included in this review were mostly from the US, where only insured patients were considered, limiting the applicability of the results to other populations. Also, the definition of persistence may vary between studies and this may have an impact on the results, especially when not considering different administration frequencies. When applicable, adjusting for the observation period and for baseline characteristics, such as biologic-experienced/naïve or line of therapy, is important when comparing persistence between treatments. In general, ixekizumab was found to have similar or better persistence versus other biologics, and rates or risk of switching that were similar or less than comparator drugs. Adherence to ixekizumab is high, and patients are less likely to discontinue ixekizumab compared with other biologics. There are fewer data on ixekizumab versus the newer anti-IL-23s, since these agents are recent additions to the market, and available evidence shows mostly numerical differences (Citation55), with some exceptions (Citation52). Some large, prospective, observational studies are underway that will provide further data on the use of ixekizumab in the changing treatment landscape of the real world (Citation60,Citation87).

Overall, the studies of clinical effectiveness included in the review reported that ixekizumab was effective in the treatment of PsO and PsA. A large study found that ixekizumab was superior to other biologic treatments with respect to PASI improvement (Citation47). Data from several studies suggest that ixekizumab is more effective in biologic-naïve patients (Citation53,Citation71,Citation72,Citation75,Citation77,Citation78), and the studies of patients with PsO who received ixekizumab after secukinumab failure demonstrated that ixekizumab is also effective when administered as second-line anti-IL-17A therapy (Citation67,Citation68).

The results from an Italian study comparing data obtained in the clinic with data from the UNCOVER-3 clinical trial suggest that, despite patient characteristics being different in the real world versus the randomized clinical trial setting, ixekizumab appears to be as effective in the real world as it is in clinical trials (Citation69). This study showed that ixekizumab may have greater effectiveness in PsO at earlier timepoints in the real world than the efficacy seen in clinical trials; however, by 20 weeks there was no longer a clear difference in response (Citation69). Another study found that secukinumab had a faster onset of action than ixekizumab, with PASI responses converging at later timepoints (Citation56). The faster onset of action of secukinumab was unexpected since indirect comparisons from phase 3 clinical trials have demonstrated better efficacy of ixekizumab at 12 weeks (Citation88), and a network meta-analysis has reported clinical benefit with ixekizumab at timepoints as early as 2 weeks (Citation89). Further investigation is needed to clarify these results.

Although many of the studies included in this review enrolled a high proportion of patients with PsO and coexisting PsA and demonstrated the effectiveness of ixekizumab in these populations, the lack of studies specifically in patients with PsA means that firm conclusions on real-world effectiveness cannot be drawn at present. Since ixekizumab was approved in 2018, it is reasonable to expect that further real-world studies of ixekizumab in patients with PsA will be published in the coming years.

The safety profile reported in real-world studies of ixekizumab in patients with PsO is consistent with that reported in clinical trials, with no unexpected safety signals identified. Injection site reactions and infections were common adverse events reported in the included publications and in the UNCOVER trials (Citation14,Citation65,Citation90). Treatment discontinuations due to adverse events also occurred at a similar rate to that seen in clinical trials.

The follow-up durations of the included studies ranged from 20 weeks to 3 years where reported, with the longest follow-up (3 years) in a study of treatment patterns (Citation44). While the long-term results of the UNCOVER-1 and −2 studies suggest that ixekizumab is effective and safe in patients with PsO when administered up to 5 years, this is yet to be confirmed in the real-world setting (Citation65).

The number of publications with a focus on PROs was low. Considering the substantial disease burden associated with these diseases and the negative impact symptoms have on patient QoL (Citation5,Citation7,Citation9–12), greater focus on these outcomes would assist in better defining treatment pathways.

Although economic studies show that direct drug-related cost is the major contributor to the costs of treatment in PsO patients receiving ixekizumab in the US (Citation83), selecting a medication with higher effectiveness is usually the most appropriate approach considering longer term outcomes (Citation91), tolerability and adherence. It should be noted that these results should not be extrapolated to other countries, as economic results vary between health systems.

The date of the literature search is a limitation of this analysis; an updated literature search of the Ovid database, congress proceedings and known Eli Lilly publications from 6 April 2021 to 8 June 2022 identified 43 new publications: 32 for PsO, 4 for PsA and 7 for PsO/PsA. Given the high number of publications in this most recent time period, a further analysis will be required to extract data from these publications and perform a comparison to the data presented in the current review. This structured literature review has some other limitations, including: the use of econlit as a literature database, potentially excluding journals that are not Medline indexed; the high number of conference abstracts (with some conferences canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic) and posters included; the lack of studies investigating PROs; that some studies had small sample sizes; and that many were retrospective in design, potentially leading to gaps in available data, such as reasons for discontinuation of ixekizumab. In line with this, there was inconsistent data reporting in studies, with many studies missing information regarding the number of PsO patients with coexisting PsA, disease severity, population sizes and follow-up times. The differences in study design, patient populations and data collection approaches meant comparison between studies was not always possible or appropriate; as such, more informative studies have been highlighted. Finally, lack of adjustment was noted in many studies for potential confounders, such as coexisting PsA and prior biologic use.

In conclusion, data from the real-world use of ixekizumab in PsO and PsA contribute to consolidating the profile of ixekizumab with high PASI responses and a safety profile similar to that seen in clinical trials. Treatment persistence with ixekizumab is high, being generally similar or longer than with other biologics; high treatment persistence may be a feature of the newer IL inhibitors versus older biologics such as the TNF inhibitors. Adherence is generally better with ixekizumab than with other biologics, and patients receiving ixekizumab tend to switch treatments less frequently than or at a similar rate to other biologics. Further work is required to determine the impact of ixekizumab on PROs in PsO, and to gather more data on the real-world use of ixekizumab in PsA.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (312.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Richard Perry and Hannah Tomkinson from Adelphi Values Limited conducted the study on behalf of Eli Lilly and Company. The authors thank Sheridan Henness and Karen Goa (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure statement

Adam Reich has received personal and institutional fees from Abbvie, Alvotech, Amgen, AnaptysBio, Argenx, Biothera, BMS, Celgene, Celltrion, Dermira, Galderma, Inflarx, Janssen, Kiniska, Kymab, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Trevi Therapeutics and UCB; honoraria from Chema Rzeszow, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Sandoz and Takeda; and has participated on advisory boards for Abbvie, Galderma, Sandoz and Sanofi Aventis. Ennio Lubrano has received honoraria for conference talks from Abbvie, Janssen Cilag, Lilly, UCB, Pfizer and Novartis. Catherine Reed, Christopher Schuster, Camille Robert and Tamas Treuer are employees of Eli Lilly and Company.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Di Meglio P, Villanova F, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014; 14(8):a015354–a015354.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(4):278–285.

- Lima XT, Minnillo R, Spencer JM, et al. Psoriasis prevalence among the 2009 AAD national melanoma/skin cancer screening program participants. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(6):680–685.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385.

- Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, et al. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the Population-Based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):87–97.

- Ocampo DV, Gladman D. Psoriatic arthritis. F1000Res. 2019;8:1665.

- Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8 Suppl):S216–S24.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):251–265 e19.

- Kwan Z, Bong YB, Tan LL, et al. Determinants of quality of life and psychological status in adults with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310(5):443–451.

- Puig L, Thom H, Mollon P, et al. Clear or almost clear skin improves the quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):213–220.

- Bulat V, Situm M, Delas Azdajic M, et al. Study on the impact of psoriasis on quality of life: psychological, social and financial implications. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(Suppl 4):553–561.

- Husni ME. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):677–698.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):541–551.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, UNCOVER-3 Study Group, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-Severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):345–356.

- Papp KA, Leonardi CL, Blauvelt A, et al. Ixekizumab treatment for psoriasis: integrated efficacy analysis of three double-blinded, controlled studies (UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, UNCOVER-3). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):674–681.

- Blauvelt A, Papp K, Gottlieb A, IXORA-R Study Group, et al. A head-to-head comparison of ixekizumab vs. guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 12-week efficacy, safety and speed of response from a randomized, double-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(6):1348–1358.

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi C, Elewski B, IXORA-R Study Group, et al. A head-to-head comparison of ixekizumab vs. guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 24-week efficacy and safety results from a randomized, double-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(6):1047–1058.

- Paul C, Griffiths CEM, van de Kerkhof PCM, et al. Ixekizumab provides superior efficacy compared with ustekinumab over 52 weeks of treatment: results from IXORA-S, a phase 3 study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):70–79 e3.

- Reich K, Pinter A, Lacour JP, IXORA-S investigators, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: 24-week results from IXORA-S, a phase III study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(4):1014–1023.

- Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, SPIRIT-P1 Study Group, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):79–87.

- Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2317–2327.

- Smolen JS, Mease P, Tahir H, et al. Multicentre, randomised, open-label, parallel-group study evaluating the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab versus adalimumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis naive to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug: final results by week 52. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(10):1310–1319.

- Mease PJ, Smolen JS, Behrens F, SPIRIT H2H study group, et al. A head-to-head comparison of the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab and adalimumab in biological-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a randomised, open-label, blinded-assessor trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):123–131.

- Reich K, Kristensen LE, Smith SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab versus adalimumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis and moderate-to-severe psoriasis: 52-week results from the randomized SPIRIT-H2H trial. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12(2):e2022104.

- US FDA. Real-world evidence 2022. https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence

- European Medicines Agency. Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU) 2022. 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/big-data/data-analysis-real-world-interrogation-network-darwin-eu

- National Insitute for Health and Care Excellence. Real-world evidence framework feedback 2022. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/real-world-evidence-framework-feedback

- European Commission. European Health Data Space 2022. 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en

- Cinelli E, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Real-world experience versus clinical trials: pros and cons in psoriasis therapy evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(3):e107–e108.

- US FDA. TALTZ (ixekizumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Prescribing information 2017. 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125521s004lbl.pdf.

- European Medicines Association. Taltz (ixekizumab) 80 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe. Summary of product characteristics 2020. 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/taltz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Costanzo A, Malara G, Pelucchi C, et al. Effectiveness end points in Real-World studies on biological therapies in psoriasis: systematic review with focus on drug survival. Dermatology. 2018;234(1-2):1–12.

- de la Cueva Dobao P, Notario J, Ferrandiz C, et al. Expert consensus on the persistence of biological treatments in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(7):1214–1223.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Higgins JPT TJ ,Chandler J ,Cumpston M, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane; 2021. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Shahriari M, Crabtree M, Burge R, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and response to treatment for patients initiating ixekizumab: findings from the corrona registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):AB252.

- Shahriari M, Harrison RW, Burge R, et al. Disease response and patient-reported outcomes among initiators of ixekizumab. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020; 2:1–9.

- Shahriari M, Harrison RW, Burge R, et al. Disease response outcomes among ixekizumab patients: findings from the corrona registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4, Supplement 1):AB194.

- Blauvelt A, Burge R, Charbonneau B, et al. 26648 Real-World comparison of monotherapy and concomitant medication use with biologic therapies for psoriasis: ixekizumab vs. Guselkumab. Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:19–23.

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi C, Lebwohl MG, et al. 16007 ixekizumab demonstrated longer medication persistence than other biologics in the treatment of psoriasis patients: results from IBM MarketScan® databases. Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:20–24

- Blauvelt A, Shi N, Burge R, et al. Comparison of real-world treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis prescribed ixekizumab or secukinumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):927–935.

- Blauvelt A, Shi N, Burge R, et al. Comparison of Real-World treatment patterns among psoriasis patients treated with ixekizumab or adalimumab. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:517–527.

- Blauvelt A, Shi N, Burge R, et al. 26718 Comparison of Long-Term treatment patterns between ixekizumab and secukinumab users among biologic-experienced psoriasis patients. Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:19–23.

- Blauvelt A, Zhu B, Murage M, et al. 26654 Ixekizumab demonstrates greater medication adherence, persistence, and longer monotherapy duration than secukinumab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and etanercept up to 3 years in the treatment of psoriasis: real-world results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(3):AB111.

- Egeberg A, Bryld LE, Skov L. Drug survival of secukinumab and ixekizumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):173–178.

- Feldman SR, Zhang J, Martinez DJ, et al. Real-world biologic and apremilast treatment patterns and healthcare costs in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(1):13030.

- Graier T, Salmhofer W, Jonak C, et al. Biologic drug survival rates in the era of anti-interleukin-17 antibodies: a time-period-adjusted registry analysis*. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(6):1094–1105.

- Hendrix N, Marcum ZA, Veenstra DL. Medication persistence of targeted immunomodulators for plaque psoriasis: a retrospective analysis using a U.S. claims database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(6):675–683.

- Kemula M, Morand F, De Nascimento J, et al. PBI58 persistence of treatment with biologics for patients with psoriasis: an analysis of a french prescription database. Value Health. 2020;23: s420.

- Leonardi CL, Blauvelt A, Zhu B, et al. 15984 Psoriasis patients treated with ixekizumab were maintained longer on monotherapy compared with other biologics in real-world clinical practice settings: results from IBM MarketScan databases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(6):AB52.

- Lockshin B, Cronin A, Harrison RW, et al. Drug survival of ixekizumab, TNF inhibitors, and other IL-17 inhibitors in real-world patients with psoriasis: the corrona psoriasis registry. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14808.

- Lunder T, Zorko MS, Kolar NK, et al. Drug survival of biological therapy is showing class effect: updated results from slovenian national registry of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(6):631–641.

- Sherman S, Zloczower O, Noyman Y, et al. Ixekizumab survival in heavily pretreated patients with psoriasis: a two-year single-Centre retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(19):adv00349.

- Stelmaszuk-Zadykowicz NM, Apol E, Hansen JB, et al. AD1 persistence of biologic therapies for the treatment of plaque psoriasis - A national longitudinal observational population study in Sweden. Value Health. 2019;22:s403.

- Torres T, Puig L, Vender R, et al. Drug survival of IL-12/23, IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis treatment: a retrospective Multi-Country, multicentric cohort study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):567–579.

- Caldarola G, Mariani M, Pirro F, et al. Comparison of short- and long-term effectiveness of ixekizumab and secukinumab in real-world practice. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21(2):279–286.

- Georgakopoulos JR, Lam K, Sandhu VK, et al. Comparative 12-week effectiveness and safety outcomes of biologic agents ustekinumab, secukinumab and ixekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a real-world multicenter retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(8):e416–e418.

- Herrera-Acosta E, Garriga-Martina GG, Suárez-Pérez JA, et al. Ixekizumab vs ustekinumab for skin clearance in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis after a year of treatment: real-world practice. Dermatol Ther. 2020b;33(6):e14202.

- Herrera-Acosta E, Garriga-Martina GG, Suárez-Pérez JA, et al. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety of secukinumab vs ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis after 1 year of treatment: real-world practice. Dermatol Ther. 2020a;33(3):e13313.

- Pinter A, Constanzo A, Gooderham M, et al. Initial Report from the Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO) on baseline characteristics and week 12 results in psoriasis patients treated with biologics in a real world setting. EADV Virtual. 2020.

- Georgakopoulos JR, Phung M, Ighani A, et al. Biologic switching between interleukin 17A antagonists secukinumab and ixekizumab: a 12-week, multicenter, retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(1):e7–e8.

- Apol E, Delgado Perala M. 6ER-011 modelling the impact of discounts on the real-life cost-effectiveness of biologic therapies in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Spain. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26(Suppl 1):A282–A283.

- Blauvelt A, Shi N, Zhu B, et al. Comparison of health care costs among patients with psoriasis initiating ixekizumab, secukinumab, or adalimumab. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(12):1366–1376.

- Leonardi C, Gara A, Amato D, et al. Disease severity and quality of life among ixekizumab-treated psoriasis patients in the real-world setting: results from a single US dermatology referral practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):AB47.

- Leonardi C, Reich K, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 5 years in moderate-to-Severe psoriasis: long-Term results from the UNCOVER-1 and UNCOVER-2 phase-3 randomized controlled trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(3):431–447.

- Leonardi C, Tao R, Setayeshgar S, et al. 14216 Long-term treatment effects of ixekizumab among psoriasis patients who achieved early high-level treatment outcomes in a real-world setting: results from a single US dermatology referral practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(6):AB133.

- Sherman S, Solomon Cohen E, Amitay-Laish I, et al. IL-17A inhibitor Switching - Efficacy of ixekizumab following secukinumab failure. A single-center experience. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019; 199(9):769–773.

- Conti A, Peccerillo F, Amerio P, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to ixekizumab in secukinumab nonresponder patients with psoriasis: results from a multicentre experience. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(6):1547–1548.

- Damiani G, Conic RRZ, Pigatto PDM, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. From randomized clinical trials to real life data. An italian clinical experience with ixekizumab and its management. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(3):e12886.

- Briceño Casado M, Gil-Sierra M, De La Calle Riaguas B, et al. 4CPS-324 effectiveness and safety of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2021;28(Suppl 1):A76.3–A77.

- Chiricozzi A, Burlando M, Caldarola G, et al. Ixekizumab effectiveness and safety in the treatment of moderate-to-Severe plaque psoriasis: a multicenter, retrospective observational study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(3):441–447.

- Deza G, Notario J, Lopez-Ferrer A, et al. Initial results of ixekizumab efficacy and safety in real-world plaque psoriasis patients: a multicentre retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):553–559.

- Georgakopoulos JR, Phung M, Ighani A, et al. Ixekizumab (interleukin 17A antagonist): 12-week efficacy and safety outcomes in real-world clinical practice. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(2):174–177.

- Goon PKC, Lim H-Y, Summerfield L, et al. Real-world experience and analyses of the performance of ixekizumab as first-line biologic agent versus second-line (or higher) biologic agent in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(8):e319–e320.

- Gulliver W, Penney M, Power R, et al. Moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis patients treated with ixekizumab: early real-world outcomes and adverse events. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;33(1):354–360.

- Hampton PS, Meeks AC, Arx LB, et al. PBI53 initiation of ixekizumab in patients with psoriasis and follow-up assessment in the badbir registry. Value Health. 2020;23: s419. 12/01

- Magdaleno-Tapial J, Carmena-Ramón R, Valenzuela-Oñate C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in a Real-Life practice: a retrospective bicentric study. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition). 2019;110(7):585–589. 2019/09/01/

- Rivera R, Velasco M, Vidal D, et al. The effectiveness and safety of ixekizumab in psoriasis patients under clinical practice conditions: a spanish multicentre retrospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14066.

- Sendín-Martín M, Barabash-Neila R, Durán-Romero A, et al. 15906 Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in real-world psoriasis patients: a retrospective unicentre study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(6):AB163. 12/01

- Grace E, Zhu B, Malley W, et al. P001 safety events occurring among patients exposed to ixekizumab in the corrona psoriasis registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(S3):3–19.

- Perrone V. Losi S, Maiorino A, et al. Treatment patterns and pharmacoutilization in patients affected by psoriasis: an observational study in an Italian real-world setting. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022;9(2):243–251.

- Wu JJ, Zhu B, Burge R, et al. Real world use of ixekizumab is associated with reductions in concomitant medications among biologic-experienced or biologic-naive patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):AB114.

- Murage MJ, Gilligan AM, Tran O, et al. Ixekizumab treatment patterns and healthcare utilization and costs for patients with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(1):56–63.

- Manfreda V, Chimenti MS, Canofari C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective, single-Centre, observational study in a real-life clinical setting. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(3):581–582.

- Murage M, Princic N, Park J, et al. Real world treatment patterns among patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with ixekizumab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10). [Accessed 22 December 2022]. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/real-world-treatment-patterns-among-patients-with-psoriatic-arthritis-treated-with-ixekizumab/

- Murage MJ, Princic N, Park J, et al. Real-World healthcare resource utilization and costs of patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with ixekizumab. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10a):S1–S101.

- Pinter A, Puig L, Schakel K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologics in clinical practice: week 12 primary outcomes from an international observational psoriasis study of health outcomes (PSoHO). Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(11):2087–2100. Jun 29.

- Warren RB, Brnabic A, Saure D, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with ixekizumab vs. secukinumab. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1064–1071.

- Warren RB, See K, Burge R, et al. Rapid response of biologic treatments of moderate-to-Severe plaque psoriasis: a comprehensive investigation using bayesian and frequentist network meta-analyses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):73–86.

- Imafuku S, Torisu-Itakura H, Nishikawa A, Japanese UNCOVER-1 Study Group, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab treatment in japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: subgroup analysis of a placebo-controlled, phase 3 study (UNCOVER-1). J Dermatol. 2017;44(11):1285–1290.

- Al Sawah S, Foster SA, Burge R, et al. Cost per additional responder for ixekizumab and other FDA-approved biologics in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(12):1224–1230.