Abstract

Background

Baricitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 inhibitor, is approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults.

Objectives

We report integrated baricitinib safety data in patients with up to 3.9-years exposure.

Methods

Three datasets from the integrated AD clinical trial program were analyzed: placebo-controlled, 2-mg–4-mg extended, and All-bari. Data cutoffs were up to 21-December-2021 for long-term extension studies. Proportions of patients with events and incidence rates (IR)/100 patient years (PY) at risk were calculated.

Results

2636 patients received baricitinib for 4628.4 PY. Discontinuation due to adverse events was low (IR = 3.4). IRs in All-bari were: serious adverse events, 5.2; infection, 67.2 (any infection), 6.7 (herpes simplex), 2.8 (herpes zoster), and 0.3 (opportunistic infections). Adverse events of special interest in All-bari included seven patients with positively adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (IR = 0.15), three pulmonary emboli (PE) (IR = 0.06), 14 malignancies excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer (IR = 0.3), one gastrointestinal perforation (IR = 0.02), and four deaths (IR = 0.1). No deep vein thromboses (DVT) or tuberculosis were reported.

Conclusion

In this analysis, baricitinib maintained a similar safety profile to earlier analyses with no new safety signals. Rates of MACE, DVT/PE, malignancies, and serious infections were within ranges of background rates in patients with AD.

Clinicaltrials.gov

NCT02576938 (JAHG), NCT03334396 (JAHL; BREEZE-AD1), NCT03334422 (JAHM; BREEZE-AD2), NCT03334435 (JAHN; BREEZE-AD3), NCT03428100 (JAIN; BREEZE-AD4), NCT03435081 (JAIW; BREEZE-AD5), NCT03559270 (JAIX; BREEZE-AD6), NCT03733301 (JAIY; BREEZE-AD7)

Introduction

Baricitinib, an oral reversible and selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 inhibitor (Citation1), is indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adult patients. In clinical trials of once-daily baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg as monotherapy or in combination with topical corticosteroids, baricitinib showed significant clinical efficacy with acceptable safety (Citation2–6). Integrated safety in 2531 patients who had 2247 patient-years (PY) of exposure to baricitinib treatment during the AD clinical development program has been previously reported (Citation7). The results of that analysis showed an increased rate of infections in baricitinib-treated patients compared to the placebo group, but most infections were mild to moderate in severity and were driven by upper respiratory tract infections and herpes simplex; there was no increase in serious infections or infections requiring antibiotic treatment in baricitinib-treated patients during the placebo-controlled period of that analysis. The number of adverse events (AEs) of special interest (major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE], deep vein thrombosis [DVT], pulmonary embolism [PE], and malignancy) was low. Due to the chronic nature of AD and the need for long-term use of systemic treatments, it is important to continuously monitor and assess the safety profile of baricitinib with cumulative exposure over time. Long-term data are most relevant to assess the incidence and risk of uncommon AEs such as MACE and malignancies. We present updated integrated data of the AD program for up to 3.9 years of treatment, representing 4628.4 PY of exposure (an additional 2381.0 PY compared to 2247.4 reported previously) (Citation7).

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients were aged 18 years or older, with moderate-to-severe AD, defined as Eczema Area and Severity Index score of ≥16 (≥12 for the phase 2 study), validated Investigator Global Assessment-Atopic Dermatitis® (vIGA-AD) score of ≥3 (not used in the phase 2 study), ≥10% body surface area involvement at baseline, and inadequate response to topical therapies and, in BREEZE-AD4, inadequate response to cyclosporine. Key exclusion criteria included concomitant skin conditions that could affect assessment of AD lesions, history of eczema herpeticum within 12 months prior to screening or ≥2 episodes of eczema herpeticum at any time previously, a venous thromboembolic event (VTE) or MACE within 12 weeks of screening or high risk for VTE. High risk was defined as having a history of recurrent VTE (≥2; not defined for BREEZE-AD5 or BREEZE-AD6) or being considered at high risk of VTE as deemed by the investigator. For BREEZE-AD5 high risk was also defined if the patient had ≥2 risk factors for VTE (aged >65 years, BMI >35 kg/m2, and a combination of oral contraceptive use with smoking).

Study design

Safety data are included from six double-blinded, randomized clinical studies (phase 2: NCT02576938; phase 3: NCT03334396 [BREEZE-AD1], NCT03334422 [BREEZE-AD2], NCT03428100 [BREEZE-AD4], NCT03435081 [BREEZE-AD5], NCT03733301 [BREEZE-AD7]), one long-term extension (LTE) study that included both a randomized, double-blinded period and open-label period (NCT03334435 [BREEZE-AD3]), and one open-label LTE (NCT03559270 [BREEZE-AD6]). Data cutoffs were up to December 21, 2021, in the ongoing LTE studies. In the BREEZE-AD3 LTE study, patients were rerandomized based on response in their originating studies and could be rescued to other doses during the LTE. In BREEZE-AD4 patients were rerandomized based on response at week 52. Study designs are described in Supplemental Table 1. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and approved by individual institutional review boards at each participating study center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), including serious adverse events (SAEs), deaths, and AEs leading to interruption or discontinuation of study drug, AEs of special interest, and laboratory changes through 120 weeks were evaluated. For some AEs of special interest, cluster analyses grouped preferred terms and terms associated with related clinical disease presentations. These clusters were informed by combining Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) standardized MedDRA queries (SMQs), and medical assessment of preferred terms and clusters previously used to establish the safety profile of baricitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. MACE, arterial thromboembolic events (ATE), and DVT/PE were identified by the clinical site or through medical review and sent to a blinded external Clinical Event Committee for adjudication. Event clusters, adjudication details, and other AE definitions are described in Supplemental Table 2.

Analysis sets

As described previously (Citation7), this analysis examined three pooled datasets:

Placebo-controlled dataset: assessed the safety profile of 2-mg and 4-mg baricitinib versus placebo during the 16-week, placebo-controlled period for patients in the phase 2 study and four phase 3 studies (BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, BREEZE-AD4, and BREEZE-AD7).

2-mg–4-mg extended dataset (extended dataset): evaluated the long-term safety profile of patients continuously treated with baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg from the randomized LTE study BREEZE-AD3, the randomized study BREEZE-AD4 through week 52, and the baricitinib 2-mg and 4-mg treatment arms of the 16-week placebo-controlled studies (phase 2 study and three phase 3 studies (BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7). BREEZE-AD3 enrolled patients from originating studies BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7 giving a total exposure up to 203 weeks of treatment (the open-label 2-mg patients from BREEZE-AD3 are not part of the extended dataset). Patients in the extended dataset were continuously treated with baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg from baseline and censored in case of dose change.

All-bari AD dataset (All-bari): evaluated the long-term safety profile of baricitinib and included data for all patients who received at least one dose (1 mg, 2 mg, or 4 mg) of baricitinib at any time from any of the eight clinical trials (phase 2 study, BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, BREEZE-AD3, BREEZE-AD4, BREEZE-AD5, BREEZE-D6, and BREEZE-AD7).

Statistical analysis

In the baricitinib AD clinical trial program, the ratio of baricitinib to placebo randomization was not the same across all studies. To provide appropriate direct comparisons between treatment groups for the placebo-controlled and extended datasets, adjusted percentages and adjusted IRs were calculated for AEs. Adjusted percentages were derived using study weights based on total sample size per study. Adjusted IRs per 100 PY at risk of observation time, with observation time censored at event date, were derived using study weights based on total PY of exposure per study. For All-bari, IRs were calculated as the number of patients with an event per 100 PY at risk of observation time with observation time censored at event date.

Results

In this analysis, 2636 patients in All-bari received ≥1 dose of baricitinib for 4628.4 PY, which represents an additional 105 patients and 2381 PY from the previous safety report (Citation7). In the extended dataset, 584 and 497 patients in the baricitinib 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively, had 727.1 and 800.1 PY exposure, representing an additional eight patients in each group and an additional 301.6 and 340.8 PY from the previous report (Citation7). The placebo-controlled dataset remained unchanged. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are presented in . In All-bari, the mean age was 36.5 years, 39.4% of patients were female, with an average of 15.0 years since diagnosis; 45.8% of patients presented with severe AD (). Sixty-three percent of patients had ≥1 year and 50% had ≥84 weeks of exposure to baricitinib with a median treatment of 1.6 years and maximum treatment of 3.9 years (); 15%, 39%, and 48% of patients who received baricitinib 1 mg, 2 mg, and 4 mg, respectively, had ≥84 weeks of exposure. The percent PY of exposure out of total PY of exposure was 9.5%, 52.3%, and 38.2% for the 1-mg, 2-mg, and 4-mg groups, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics and disease activity.

Table 2. Overview of safety measures including drug exposure, treatment-emergent adverse events, and adverse events of special interest.

Treatment-emergent adverse events

Overall, 2040 patients reported at least one TEAE for an IR of 145.8 in All-bari; IRs in the extended dataset were 214.7 and 216.3 for the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively. Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity. As in the previous report, the most common TEAEs remained infections (IR, 67.2 in All-bari versus 91.7 previously (Citation7)), primarily upper respiratory tract infections and herpes simplex (), the majority of which were mild or moderate in severity. The IRs for all of these common TEAEs decreased since the previous report (Citation7). In All-bari, the IR for SAEs was 5.2 (versus 6.1 previously (Citation7)). The most common SAEs were infections (IR, 1.8), followed by skin disorders (IR, 1.0) and the most frequently reported individual event was atopic dermatitis (worsening of AD) (IR, 0.8). In the extended dataset, the IR for SAEs was higher in the 4-mg group (7.9) versus the 2-mg group (4.2) and atopic dermatitis was the most frequently reported SAE preferred term in both dose groups.

Table 3. Adverse events detail.

There were three new deaths in All-bari since the previous report resulting in a total of four (IR, 0.1), with no deaths reported in the extended dataset. In addition to the previously reported death due to gastrointestinal bleed in a 53-year-old male (presenting with low hematocrit at study entry and on baricitinib for 375 days), the causes of the three additional deaths were: sudden death (unknown cause, no autopsy performed) in a 71-year-old male on baricitinib for 761 days who had cardiovascular risk factors of being a current smoker and medical records indicating hypercholesterolemia; small-cell lung cancer in a 70-year-old male on baricitinib for 609 days who was a current smoker on study entry; and cerebral hemorrhage that occurred 2.5 h after thrombolysis treatment in a 53-year-old male on baricitinib for 798 days who was hospitalized with sepsis due to cholecystitis and embolic stroke.

The IRs of permanent study drug discontinuation due to AEs remained low with an overall IR in All-bari of 3.4 per 100 PY at risk (). The most common System Organ Class of permanent discontinuation remained skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (), reported by 22% of patients who discontinued and over half of those (54%) was due to worsening AD. The IRs of temporary interruptions of study drug due to AEs in All-bari and extended datasets were similar to the previous report () (Citation7) and were most frequently due to infections in all datasets (63% in All-bari, 68% in 2 mg, and 67% in 4 mg of extended dataset). Most infections were mild or moderate in severity and often the treatment interruption was driven by study protocol requirements.

Adverse events of special interest

Infections

Most treatment-emergent infections were mild or moderate in severity and the IRs decreased with longer exposure. The IRs of serious infection in the extended dataset (1.4 and 2.7 in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively) and All-bari dataset (1.8) () remained consistent with the previous report (Citation7). The most common serious infections in All-bari were eczema herpeticum (n = 13, IR = 0.3), cellulitis (n = 9, IR = 0.2), erysipelas (n = 4, IR = 0.1), pneumonia (n = 4, IR = 0.1), and COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 3, IR = 0.1). For patients reporting skin infections that required antibiotic treatment, as with the previous report, in the extended dataset the IR was lower in the 4-mg (2.5) versus the 2-mg (4.5) group and the more common preferred terms were skin infection, folliculitis, cellulitis, and impetigo.

There were no reports of tuberculosis. In All-bari there were ten additional opportunistic infections (n = 14; IR = 0.3) from the previous report: eight additional herpes zoster, one herpes ophthalmic, and one typhoid fever. Of the 12 herpes zoster, six were multidermatomal and six were disseminated. The overall IR for all herpes zoster was 2.8 in All-bari (versus 2.3 in the previous report (Citation7)) and 3.2 and 3.0 in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups of the extended dataset, respectively (versus 3.8 and 1.8 previously (Citation7)). In All-bari, IRs for herpes zoster were similar across age groups (IR = 2.79, 2.84, and 2.23 for <50, ≥50 to <65, and ≥65, respectively). Additionally, in All-bari, two patients reported SAEs of herpes zoster and herpes zoster events led to permanent discontinuation in three patients; for 95% of patients with herpes zoster, the events were mild or moderate in severity and 94% of patients had recovered at the time of data cutoff.

The IRs for herpes simplex in the extended dataset (2 mg, 7.5 and 4 mg, 10.7) and All-bari dataset (6.7) were decreased from the previous report (All-bari IR 10.3 [7]). The majority (94%) were mild or moderate in severity and the most common preferred terms were oral herpes (n = 140), herpes simplex (n = 120), and eczema herpeticum (n = 67) (Supplemental Table 3). Two events of eczema herpeticum led to permanent discontinuation and 27 events led to temporary interruption of study drug. Of 67 patients who reported eczema herpeticum or Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, a majority (64.2%) had poor disease control prior to the event (vIGA-AD scores of 3 or 4).

Cardiovascular events

There were five additional patients with MACE events since the previous report in All-bari (n = 7; IR, 0.15), two of which were included in the extended dataset (one each in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups). The eight events that occurred in seven patients were cardiovascular death (n = 2; one patient on 2 mg and one patient on 4 mg), myocardial infarction (n = 3; two patients on 2 mg and one patient on 4 mg), and stroke (n = 3; two patients on 2 mg, and one on 4 mg); one patient on 2 mg had both stroke and cardiovascular death. Six of the seven patients with MACE in this analysis had ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor at baseline, while one patient with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm had no cardiovascular risk factors at baseline. In this study, cardiovascular risk factors were history of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dL. There were four ATEs in All-bari (IR, 0.09), three of which were also adjudicated to be MACE: two myocardial infarctions (one patient each on 2 mg and 4 mg) and one embolic stroke (patient on 2 mg). The fourth ATE was previously reported in an integrated analysis of baricitinib 2 mg (arterial bypass thrombosis in All-bari 2 mg) (Citation8).

There was one additional pulmonary embolism in All-bari from the previous report (n = 3; IR, 0.06) in a 24-year-old female, treated with baricitinib 4 mg who had concomitant use of oral contraceptives and family history of coagulation disorder. The patient discontinued study treatment and recovered from the event. There were no DVTs and one event, as previously reported (Citation7), that was adjudicated as peripheral venous thrombosis.

Malignancies

In All-bari, there were nine additional patients with malignancies other than nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) versus the previous report (n = 14; IR, 0.30, ) (Citation7); two of these were in the 2-mg group of the extended dataset and none were in the 4-mg extended group. Preferred terms and baricitinib dose at time of event in All-bari included prostate cancer (n = 4, three on 2 mg and one on 4 mg), anaplastic large cell lymphoma T- and null-cell types (n = 1; 4 mg), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1; 2 mg), follicular lymphoma (previously reported as B-cell lymphoma) (n = 1; 2 mg), Hodgkin’s disease (n = 1; 4 mg), lung adenocarcinoma (n = 1; 2 mg), peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified (n = 1; 4 mg), rectal cancer (n = 1; 2 mg), small-cell lung cancer metastatic (n = 1; 2 mg), testis cancer (n = 1; 1 mg), and uterine cancer (n = 1; 2 mg). Details for each patient with malignancy are listed in Supplementary Table 4. In All-bari, five additional patients reported NMSC compared with the previous report bringing the total to 11 patients, with similar IR (0.23); two of these were reported in the extended dataset (one in 2 mg and one in 4 mg) (). The preferred terms were basal cell carcinoma (n = 6), Bowen’s disease (n = 3), keratoacanthoma (n = 1), and squamous cell carcinoma (n = 2); one patient had events of Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma.

Gastrointestinal disorders

One gastrointestinal perforation was reported (an acute perforated appendix in a patient on 4 mg).

Conjunctival disorders

Within the SMQ cluster of conjunctival disorders, in the extended dataset, IRs were similar between doses (2 mg, 3.6; 4 mg, 3.7), consistent with the previous report (Citation7). In All-bari, IRs decreased from 4.3 (CitationCitation7) to 3.2. The most commonly reported preferred terms were conjunctivitis (41% of conjunctival disorders in All-bari) and allergic conjunctivitis (34%).

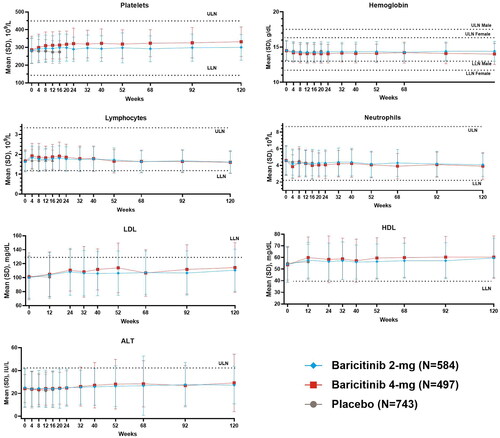

Lab evaluations

Mean changes from baseline for laboratory values remained consistent with the previous report (Citation7). Over the longer observation period through 120 weeks no changes of clinical relevance were noted ().

Discussion

Baricitinib, an oral selective inhibitor of JAK1/JAK2, inhibits elements of the inflammatory pathway (Citation1). These elements are key mechanisms for chronic, inflammatory diseases but, as with all drug treatments, baricitinib can be associated with undesirable effects. In a previous integrated analysis of safety across eight clinical trials in moderate to severe AD, the most common TEAEs that increased relative to placebo were headache, increased creatine phosphokinase, herpes simplex, and upper respiratory tract infections, while the frequencies of AEs of special interest were low (Citation7). These AEs of special interest have been identified from clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in rheumatologic disease as events of concern or of potential relevance to this class of drug and include herpes virus reactivation, serious infections, malignancy, and cardiovascular events (Citation9,Citation10). In this report, we present an updated assessment of pooled safety data of baricitinib in patients with AD through 3.9 years of treatment for a total of 4628.4 years of patient exposure. Baricitinib maintained a safety profile similar to that previously reported in AD (Citation7), with rates in All-bari of adverse events of special interest that were low and within the range of background rates observed in AD populations.

Patients with AD have increased susceptibility to cutaneous and systemic bacterial and viral infections (Citation11–14). The risk of serious infection, varicella zoster virus, and herpes simplex reactivation, including eczema herpeticum, are all increased in patients with AD, and the risk increases in patients with severe disease (Citation15,Citation16). With longer exposure, the IR of herpes simplex decreased from the previously reported 10.3 (Citation7) to 6.7 in All-bari in the current analysis. Additionally, the IR of skin infections requiring antibiotics in All-bari decreased with longer exposure from 3.4 in the previous report (Citation7) to the current IR of 1.7 and was lower than in the placebo-controlled period, suggesting that control of AD lesions may reduce the risk of these AEs with long-term treatment. In this analysis, as in previous safety analyses of baricitinib in patients with AD, cases of eczema herpeticum, a disseminated skin infection caused by the herpes simplex virus, were linked to poor disease control. This supports the notion that eczema herpeticum lesions are typically only found in skin areas with previous underlying AD (Citation17) and specifically in patients with severe disease (Citation15,Citation18).

In this analysis, the rate of herpes zoster in All-bari was lower compared to the earlier data cutoff (Citation7) and there was no dose-dependent relationship with baricitinib. In general, the majority of herpes zoster cases were mild to moderate in severity and had resolved by the data cutoff. In a previous analysis of herpes zoster in a baricitinib rheumatoid arthritis clinical trial population, age was an independent risk factor for developing herpes zoster (Citation19), but no risk factors for herpes zoster were identified in an earlier safety analysis of herpetic infections in the baricitinib AD clinical trial population (Citation20). Similarly, with updated safety data in the current analysis, there was no clear trend for an increase in IR of herpes zoster with increasing age.

The most recognized opportunistic infection associated with JAK inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is herpes zoster (Citation21) and, in this analysis, while the frequency of opportunistic infections was low, the majority (85.7%) were herpes zoster. In the baricitinib clinical trial program, for herpes zoster to be classified as an opportunistic infection, it had to be a multidermatomal (>3 contiguous dermatomes or >2 noncontiguous dermatomes) and/or disseminated infection, which may differ from definitions in other study programs.

Conjunctival disorders are common in patients with AD, who have an increased risk of allergic, atopic, and infectious conjunctivitis (Citation22,Citation23). Conjunctivitis has been reported in a higher proportion of patients with AD treated with dupilumab (8.6–22.1%) versus placebo-treated patients (2.1–11.1%) (Citation24). In the previous analysis of baricitinib, the IR for the cluster of conjunctival disorders (4.3/100 PY) (Citation7) in All-bari was lower than reported in dupilumab (9.7/100 PY) (Citation25) and has further decreased in the current analysis to 3.2. Since conjunctivitis has not been an issue in patients treated with baricitinib as evidenced by a lower frequency in baricitinib-treated patients compared to placebo during the placebo-controlled dataset and no increase in IRs over time, baricitinib may represent a reasonable treatment option for patients who are concerned about or experience eye symptoms with dupilumab.

There are conflicting data around the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with AD. While some studies show a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with mild AD (Citation26), more data suggest a slightly increased risk of cardiovascular disease including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death in patients with AD compared with the general population, especially in patients with more severe disease. However, the absolute rates for MACE in patients with AD are low, ranging from IRs of 0.05 to 0.21 per 100 PY for myocardial infarction, 0.07 to 0.28 per 100 PY for stroke, and 0.08 to 0.44 per 100 PY for cardiovascular death (Citation26,Citation27). IRs of composite MACE ranged from 0.15 per 100 PY for mild AD to 0.63 per 100 PY for severe disease in real-world evidence (Citation26), with ranges of 0.1 to 0.18 in clinical trials of patients with AD receiving JAK inhibitors (Citation28,Citation29). In the current analysis, the IR of MACE was 0.15, which falls within the lower limit of the range of background rates in AD patients. Six of the seven patients with MACE in this analysis had at least one cardiovascular risk factor; one patient with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm had no cardiovascular risk factors at baseline. In other indications where JAK inhibitors are treatment options, such as rheumatoid arthritis, the risk of cardiovascular disorders including MACE and its components is higher owing in part to those patients generally being older, and more frequently experiencing multiple comorbidities while receiving concomitant non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or low-dose systemic glucocorticoid therapy (Citation30).

Thromboembolic events are a recognized adverse drug reaction of JAK inhibitors. Unlike other disorders treated with JAK inhibitors such as rheumatoid arthritis, patients with immune-mediated skin disorders have less risk for VTE, although some data suggest that patients with moderate-to-severe AD may be at increased risk, most likely resulting from associated comorbidities (Citation31). IRs of 0.18 to 0.24 have been reported for PE/DVT in patients with AD, although study exclusion criteria limited patients to those with no history of VTE (Citation31). The risk for VTE (DVT/PE) with baricitinib remained in a similarly low range to that of patients with AD, with the current analysis showing a rate of 0.06, remaining stable from our previous report of 0.09 (Citation8).

Data are inconsistent regarding the association between AD and the risk of cancer. An increased risk of lymphomas has been found with severe AD with adjusted odds ratio of lymphoma in patients with severe AD ranging from 2.4 to 3.72 in case control studies (Citation32). Evidence for the relationship of other types of cancer with AD is inconclusive, with some studies showing no associations while others show inverse associations (Citation33), although an increased risk of NMSCs, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been shown (Citation34,Citation35). In the current analysis, the IR of malignancies excluding NMSC (0.30) is in line with the background rate in patients with AD (IR, 0.12–0.85) (Citation36,Citation37) and 5/14 patients with malignancies excluding NMSC had lymphoma with no dose-relationship. Of the 11 patients with NMSC, the majority (n = 6) had BCC with two patients reporting SCC. In this study, although only a small number of skin cancer events were identified, the BCC:SCC ratio was 3:1, in line with observations in the immunocompetent general population (Citation38–40).

Some concerns regarding risks associated with JAK inhibitor use have been triggered by safety findings in the rheumatoid arthritis population. Among patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were older than 50 years of age and had at least one additional cardiovascular risk factor, the risk of MACE and cancer was higher in patients treated with tofacitinib as compared to a tumor necrosis factor-inhibitor (Citation41). The chronic systemic inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with an increased risk of MACE, VTE, and certain types of malignancy (lymphoma, lung cancer), while the impact of AD on these risks is small (Citation42). In AD, the most prominent risk factors for MACE are those related to systemic corticosteroid treatment (obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus) together with sleep disruption and depression (Citation42). Risk of serious infections is closely related to underlying disease and the level of concomitant immunosuppressive treatment the patient is receiving. While in the target rheumatoid arthritis population immunosuppression is more profound due to the high prevalence of concomitant use of systemic corticosteroids and conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, it is less frequent in the AD population.

A limitation in this study is that IRs provide an estimate of the number of patients experiencing an event per 100 patient-years and should be viewed in context with IRs from the literature; however, comparisons are for context only. Inferences cannot be made as study and treatment are confounded and risk over time can change due to reasons other than treatment exposure. Regarding malignancies and MACE, longer treatment duration is required to better evaluate risks and patients who discontinued treatment in our studies due to nonresponse may have a different risk profile compared to those who continued in the studies.

Conclusions

This safety report of long-term data in the AD clinical program contributes to the ongoing safety assessment of baricitinib in treating patients with dermatologic conditions. A recently reported integrated safety assessment in patients with severe alopecia areata was consistent with the known safety profile of baricitinib (Citation43), and a review of the safety of baricitinib across different indications including other autoimmune diseases of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus highlights the differences in background risk with these different populations (Citation30). This analysis showed that in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, baricitinib maintained a similar safety profile to earlier analyses with no new safety signals. Rates of MACE, DVT/PE, malignancies, and serious infections were within the range of background rates in patients with AD.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (180 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the investigators and patients who have participated in the baricitinib atopic dermatitis clinical trial program. The authors also like to acknowledge Kathy Oneacre, MA (Syneos Health, Morrisville, NC, USA) who provided medical writing support and Antonia Baldo (Syneos Health, Morrisville, NC, USA) who provided editing support that was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure statement

Thomas Bieber reports personal fees from Eli Lilly and Company during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AbbVie, Affibody, Almirall, AnaptysBio, Arena Pharma, Asana BioSciences, ASLAN Pharma, Bayer Health, BioVersys, Böehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Connect Pharma, Dermavant, Domain Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Company, EQRx, Galderma, Glenmark, GSK, Incyte, Innovaderm, IQVIA, Janssen, Kirin, Kymab, LEO, LG Chem, L’Oréal, MSD, Novartis, Numab, OM Pharma, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Q32bio, RAPT, Sanofi/Regeneron, UCB Pfizer, Bayer, AbbVie, Sanofi-Genzyme, LEO, Galapagos, Glenmark, Galderma, Almirall, AnaptysBio, Arena Pharma, Asana BioSciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Incyte, Kymab, Menlo, Novartis, and UCB outside the submitted work.

Norito Katoh reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly Japan, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Torii Pharamacuetical; personal fees from Celgene Japan; grants from A2 Healthcare, Eisai, and Sun Pharma outside the submitted work.

Eric Simpson reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharmaceutical, Medimmune, Pfizer, Regeneron; grants from Celgene, Galderma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Merck, Novartis, Tioga; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Dermira, Forte Bio, Incyte, Menlo Therapeutics, Ortho Dermatologics, Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, Sanofi, Valeant.

Marjolein de Bruin-Weller reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and UCB outside the submitted work.

Diamant Thaci reports personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Asana Biosciences, Biogen Idec, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sandoz, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, and UCB and grants from AbbVie, LEO Pharma, and Novartis during the conduct of the study.

Antonio Torrelo reports other from Eli Lilly and Company during the conduct of the study; other from AbbVie, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi outside the submitted work.

Angelina Sontag, Susanne Grond, Maher Issa, Tracy Cardillo, and Katrin Holzwarth are employees and stockholders with Eli Lilly and Company

Xiaoyu Lu has no conflicts to report.

Jacob P Thyssen is an advisor for AbbVie, Almirall, Arena Pharmaceuticals, ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, Coloplast, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharma, OM Pharma, Union Therapeutics, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme, a speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme, and received research grants from Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

Data availability statement

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and the European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fridman JS, Scherle PA, Collins R, et al. Selective inhibition of JAK1 and JAK2 is efficacious in rodent models of arthritis: preclinical characterization of INCB028050. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):5298–5307.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):913–921.e9.

- Simpson EL, Lacour J-P, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):242–255.

- Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1333–1343.

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):62–70.

- Bieber T, Reich K, Paul C, BREEZE-AD4 study group, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with inadequate response, intolerance or contraindication to ciclosporin: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (BREEZE-AD4). Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(3):338–352.

- Bieber T, Thyssen JP, Reich K, et al. Pooled safety analysis of baricitinib in adult patients with atopic dermatitis from 8 randomized clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(2):476–485.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(3):395–405.

- Adas MA, Alveyn E, Cook E, et al. The infection risks of JAK inhibition. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(3):253–261.

- Fleischmann R. Recent issues in JAK inhibitor safety: perspective for the clinician. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(3):295–307.

- Ong PY, Leung DY. Bacterial and viral infections in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(3):329–337.

- Langan SM, Abuabara K, Henrickson SE, et al. Increased risk of cutaneous and systemic infections in atopic dermatitis – a cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(6):1375–1377.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis and serious cutaneous, multiorgan and systemic infections in US adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):66–72.e11.

- Droitcourt C, Vittrup I, Kerbrat S, et al. Risk of systemic infections in adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):290–299.

- Wan J, Shin DB, Syed MN, et al. Risk of herpesvirus, serious and opportunistic infections in atopic dermatitis: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(4):664–672.

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Association of herpes zoster and chronic inflammatory skin disease in US inpatients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(6):1437–1445.

- Seegraber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum—a retrospective european multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(5):1074–1079.

- Beck LA, Boguniewicz M, Hata T, et al. Phenotype of atopic dermatitis subjects with a history of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2):260–269.

- Winthrop KL, Harigai M, Genovese MC, et al. Infections in baricitinib clinical trials for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(10):1290–1297.

- Werfel T, Irvine AD, Bangert C, et al. An integrated analysis of herpes virus infections from eight randomized clinical studies of baricitinib in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(9):1486–1496.

- Thomas K, Vassilopoulos D. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of targeted synthetic therapies. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2020;31(Suppl 1):129–136.

- Chen JJ, Applebaum DS, Sun GS, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):569–575.

- Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):280–286.e1.

- Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(3):459–473.

- Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Beck LA, et al. Infections in dupilumab clinical trials in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive pooled analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(3):443–456.

- Andersen YMF, Egeberg A, Gislason GH, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular death in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):310–312.e3.

- Silverwood RJ, Forbes HJ, Abuabara K, et al. Severe and predominantly active atopic eczema in adulthood and long term risk of cardiovascular disease: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k1786.

- Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, Nosbaum A, et al. Integrated safety analysis of abrocitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis from the phase II and phase III clinical trial program. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(5):693–707.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Rinvoq assessment report. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/rinvoq-h-c-004760-x-0006-g-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf.

- Bieber T, Feist E, Irvine AD, et al. A review of safety outcomes from clinical trials of baricitinib in rheumatology, dermatology and COVID-19. Adv Ther. 2022;39(11):4910–4960.

- Meyers KJ, Silverberg JI, Rueda MJ, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism among patients with atopic dermatitis: a cohort study in a US administrative claims database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):1041–1052.

- Legendre L, Barnetche T, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of topical treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(6):992–1002.

- Brunner PM, Emerson RO, Tipton C, et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin shares similar T-cell clones with lesional tissues. Allergy. 2017;72(12):2017–2025.

- Jensen AO, Svaerke C, Kormendine Farkas D, et al. Atopic dermatitis and risk of skin cancer: a danish nationwide cohort study (1977–2006). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(1):29–36.

- Gandini S, Stanganelli I, Palli D, et al. Atopic dermatitis, naevi count and skin cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84(2):137–143.

- Arana A, Wentworth CE, Fernández-Vidaurre C, et al. Incidence of cancer in the general population and in patients with or without atopic dermatitis in the U.K. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(5):1036–1043.

- Mansfield KE, Schmidt SAJ, Darvalics B, et al. Association between atopic eczema and cancer in England and Denmark. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(10):1086–1097.

- Chahal HS, Rieger KE, Sarin KY. Incidence ratio of basal cell carcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma equalizes with age. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):353–354.

- Ciążyńska M, Kamińska-Winciorek G, Lange D, et al. The incidence and clinical analysis of non-melanoma skin cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4337.

- Jiyad Z, Marquart L, Green AC. A call to standardize the BCC: SCC ratio. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(3):545.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, ORAL Surveillance Investigators, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316–326.

- Drucker AM, Harvey PJ. Atopic dermatitis and cardiovascular disease: what are the clinical implications? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(5):1736–1738.

- King B, Mostaghimi A, Shimomura T, et al. Integrated safety analysis of baricitinib in adults with severe alopecia areata from two randomized clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022; ljac059. DOI:10.1093/bjd/ljac059