Abstract

Vitiligo is a chronic pigmentary condition and severely impacts patient quality of life (QoL). It is an underrecognized burden for patients, healthcare systems, and society in Latin America (LA). This paper examines the journey of a vitiligo patient in LA and assesses the disease landscape. Americas Health Foundation (AHF) assembled a panel of six Argentine, Brazilian, Colombian, and Mexican vitiligo experts. On 10–12 May 2022, they met in a virtual meeting. Each panelist wrote a short paper on barriers to vitiligo diagnosis and treatment in LA before the meeting. AHF staff moderated as the panel reviewed and modified each paper over three days. The panel approved the recommendations based on research, professional opinion, and personal experience. The panel agreed that lack of disease awareness and research, social ostracization, and limited therapeutic options hinder patients in their quest for diagnosis and treatment. In addition to the medical and psychological difficulties associated with vitiligo, problems connected to the Latin American healthcare system may negatively impact diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Access to timely diagnosis and treatment is crucial for improving outcomes. Governments, medical societies, academics, patient organizations, industry, and the public must unite to eliminate these challenges.

Introduction

Vitiligo is an acquired, persistent pigmentary condition that represents an underrecognized burden for patients, healthcare systems, and society in Latin America (LA). The loss of melanocytes causes depigmented macules or patches of varying sizes on the skin and mucous membranes. It has a complex etiology with a dynamic interplay between genetic and environmental risks that trigger autoimmunity (Citation1). This systemic condition is associated with other autoimmune conditions and affects extra-cutaneous organs like the eyes and inner ear (Citation2,Citation3). Vitiligo affects children and adults of both sexes equally, with a slight predominance in women, possibly because they are more likely to report the condition due to cosmetic and societal pressures. It may develop at any age but appears in childhood and adolescence in 50% of cases (Citation4). Despite affecting all phototypes, vitiligo disproportionately impacts those with dark skin (phototypes III–VI) because lesions are more noticeable (Citation5,Citation6). It is classified into segmental vitiligo (SV), which is localized, unilateral, and stable, and non-segmental vitiligo (NSV), a more common disseminated form that is bilateral and progressive (Citation7).

Vitiligo has severe emotional and psychological effects on patients’ quality of life (QoL). Lack of knowledge about vitiligo and its cause promotes stigma and discrimination about its transmissibility (Citation8–10). Moreover, vitiligo is not always recognized as a systemic medical disorder with comorbidities that require multidisciplinary medical care. This publication reviews the patient journey of people with vitiligo in LA, evaluates the disease landscape as perceived by dermatologists, assesses unmet needs, and provides recommendations to improve disease management and increase access to care.

Materials and methods

Americas Health Foundation (AHF) assembled a panel of six dermatologists who are experts in vitiligo and its accompanying comorbidities from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. On 10–12 May 2022, they had a three-day virtual meeting to develop recommendations for overcoming the obstacles to vitiligo diagnosis and treatment in LA. AHF used PubMed, MEDLINE, and EMBASE to discover vitiligo scientists and clinicians from LA. Augmenting this search, AHF contacted thought leaders from LA’s medical community to confirm that the list accurately represented the required specialties. All the experts who attended the meeting are named authors of this manuscript.

Search strategy

AHF researched vitiligo PubMed, MEDLINE, and EMBASE. ‘Treatment,’ ‘diagnosis,’ ‘quality of life,’ ‘patient journey’ in combination with ‘Latin America,’ and ‘vitiligo’ were searched with dates ranging from 01/01/2016 until 04/10/2021. The articles identified were in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. Literature and research from LA were prioritized.

AHF developed specific questions to address barriers limiting access to vitiligo diagnosis and treatment in LA and assigned one to each panel member. A written response to each question was drafted by individual panel members based on the literature review and personal expertise. The entire panel reviewed and edited each narrative during the three-day conference through numerous rounds of discussion until a total agreement was reached. An AHF staff member moderated the discussion. When the panel disagreed, additional discussions were held until everyone agreed on the paper’s content. The recommendations developed were based on the evidence gathered, expert opinion, and personal experience and were approved by the entire panel.

To increase local data, an online survey, available in Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese, was disseminated electronically through the Google Forms platform to dermatologists across LA, with 21 questions developed by the authors on different aspects related to care, use of clinimetry (indexes, rating scales and other expressions that are used to describe or measure symptoms, physical signs, and other clinical phenomena), and treatment, among others. It was completed by 292 participants from public and private institutions across 11 LA countries: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay. See for population characteristics. The recommendations developed were based on the evidence gathered, expert opinion, and personal experience and were approved by the entire panel. After the conference, the final manuscript was distributed by email to the panel for review and approval. The authors retain control over the paper’s content.

Table 1. Characteristics of survey sample.

Results

Epidemiology of vitiligo in LA and region-specific factors

Epidemiologic data on vitiligo is scarce and inconsistent globally, especially in LA. The global prevalence is 0.5–2% in children and adults (Citation8,Citation11,Citation12). Further vitiligo research is needed to capture the region’s epidemiology accurately. A meta-analysis (Citation13) of 103 studies from 30 countries on all continents, including Brazil and Mexico, found that global vitiligo prevalence ranged from 0.004 to 9.98%. Community-based studies in LA report a 0.4% prevalence, while hospital-based studies report 1.5%. According to three articles, vitiligo prevalence in Mexico ranges from 0.21 to 4% (Citation14). In Brazil, the prevalence ranged from 0.04 to 0.54% (Citation6).

Influencing factors

The genetic and environmental causes of vitiligo are well-documented, but the underlying mechanisms are complex (Citation8). Despite the lack of genetic investigations in LA, a positive family history of vitiligo was discovered in patients from Colombia (15%), Brazil (18%), and Mexico (26%) (Citation8,Citation15,Citation16). Children with vitiligo in Mexico have a familial history among first- (73%) and second-degree relatives (27%) (Citation17). A personal or familial history of autoimmune diseases is associated with more severe forms of vitiligo (Citation18). Monozygotic twins had a concordance rate of only 23%, highlighting the influence of the environment on vitiligo development (Citation19). Emotional stress is believed to be a trigger, but data remains limited (Citation8). In a study of 701 Brazilian children, 67% of cases of vitiligo were induced by emotional causes (Citation15). Physical trauma is also a trigger for vitiligo, as demonstrated by Koebner’s phenomenon, a sign of disease activity (Citation8). Additionally, halo nevus is a risk factor for vitiligo (Citation15,Citation20). Low socioeconomic status may influence disease control, treatment adherence, QoL declines, and heightened stigmatization.

Comorbidities

Other comorbidities exacerbate vitiligo exist (Box 1) and must be inquired about in every patient. Multiple studies have shown that up to 25% of people with vitiligo also experience other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions (Citation15,Citation17,Citation21). In Mexico, 8% of patients with vitiligo had comorbidities, including type I diabetes mellitus (4%), hyperthyroidism (2%), and alopecia areata (1.3%) (Citation17). Similarly, a Brazilian study on childhood vitiligo found that 6.7% of patients had autoimmune comorbidity at the initial visit; in the NSV group, 9.8% had hypothyroidism, 2.9% had alopecia areata, and <1% hyperthyroidism, pernicious anemia, or diabetes. In the SV group, 2.9% had hypothyroidism, and 3.4% had alopecia areata. About 70% of patients with SV and 62.5% with NSV exhibited emotional distress (Citation15). To grasp the entire scope of the disease, the link between various systemic comorbidities must be investigated, utilizing the experience of other immune-mediated diseases with dermatological symptoms, such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis (Citation22).

Vitiligo disease burden and impact on quality of life

Like any chronic condition, the burden of vitiligo must be assessed in human, societal, economic, and productivity terms (Citation18). These types of assessments are lacking in LA. Psychosocial comorbidities have been reported in over 50% of patients with vitiligo (Citation23,Citation24). Depression in some patients can be so severe that they have elevated suicide risk (Citation25). In Brazil, 26% of parents or caregivers and 42% of children with vitiligo experienced despair and anxiety (Citation23). In Mexico, depression prevalence was 34%, and anxiety was 60% among people with vitiligo (Citation17).

Skin appearance has historically been seen as a reflection of health, so many skin conditions negatively affect patients’ psychosocial well-being. Visible changes to the skin, such as pigmentation changes, have been stigmatized (Citation16). Vitiligo dramatically affects patients’ QoL like other chronic dermatological conditions, such as AD and psoriasis, and is comparable to severe non-dermatological diseases, such as cancer (Citation26,Citation27). However, vitiligo typically receives less attention than other disorders.

Female gender, age of onset, phototype, and lesion extension and distribution may influence the impact of vitiligo on QoL (Citation5). Children and adolescents experience a higher impact. Their self-esteem is affected; as a result, they shun athletics and have a high rate of school absences (Citation26). Frequent comorbidities include depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders, bullying, suicide ideation, etc. These consequences may continue into adulthood (Citation28,Citation29).

In a study including 300 individuals stratified by phototype, those with darker skin experienced a greater burden in daily life; however, disease-associated global stress was similar across the two groups (Citation5). In Brazil, most patients with vitiligo in sun-exposed areas (88%) expressed unpleasant emotions compared to those with lesions in covered areas (20%). Fear of disease progression, shame, melancholy, and self-consciousness are negative emotions experienced by more than 50% of patients (Citation30). Patients with vitiligo frequently utilize clothing and cosmetics to conceal their lesions (Citation31,Citation32).

QoL impact can be measured with general instruments like the Dermatological Life Quality Index (DLQI) or specific instruments like the Vitiligo Impact Scale and Vitiligo-specific Health-related Quality of Life Instrument (VitiQoL) (Citation9). A study of 117 patients in Brazil revealed a substantial correlation between total VitiQoL and DLQI scores (r = 0.81; p < 0.001). Stigma was the most impactful component of VitiQoL, and women scored higher than men. Psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher impact on QoL. The Child DLQI ranged from 1.3–7.3 in the pediatric population, with values increasing with age. The most vulnerable groups were women, adolescents, and patients with psychiatric conditions (Citation33).

Similarly, a study conducted in Mexico of 150 adult patients with vitiligo revealed a strong correlation between both questionnaires (0.675, p < 0.001). Low-intermediate DLQI (5.2 ± 5.4) and VitiQoL (32.1 ± 22.7) values were observed. The VitiQoL of patients with genital involvement was substantially higher (Citation17).

In a Colombian study of 110 adult patients with vitiligo, 92.7% received low-intermediate DLQI scores (<10) and a mean VitiQoL score of 31.29, with the most considerable impact on the behavioral and stigmatization spheres and correlated positively with disease extension. Although these ratings are not exceptionally high, presumably due to a modest percentage of the damaged body surface, women had higher scores. These findings closely resemble those of Brazilian and Mexican studies (Citation34). The currently available tools for measuring QoL only evaluate a brief point in time of chronic disease and fail to quantify the condition’s cumulative life impairment. Consequently, they may underrepresent the true impact of the disease.

British guidelines recommend evaluating and monitoring the impact on QoL and mental health. The latter can be accomplished using Patient Health Questionnaire-4, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and/or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaires (Citation9). Disease extension should also be objectively measured. Vitiligo extent score (VES) and VESplus are the most validated tools for this purpose. Others include the Vitiligo European Task Force assessment (VETF) and Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI). The latter helps define severity, combining extension with the degree of depigmentation (Citation35). The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI) can be used to measure the impact on quality of life in children and the patient’s family or caregivers, respectively (Citation36,Citation37). With the advent of new therapies, clinimetric tools will be essential to guide treatment decisions and monitor response.

Landscape of access to vitiligo management in LA

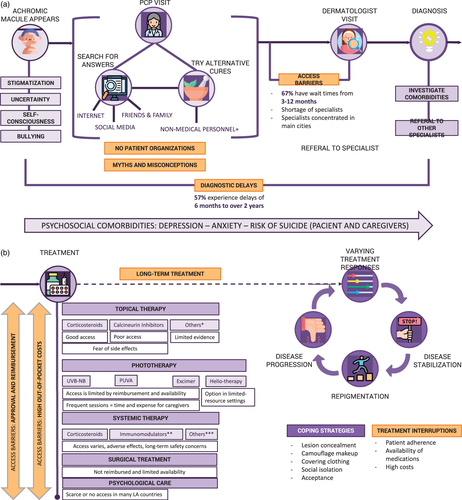

LA is a multicultural, ethnically diverse region, and each country’s healthcare system is unique. The typical patient journey of a person with vitiligo in LA is winding and rife with barriers resulting in delays in diagnosis and treatment that may alter their prognosis ().

Figure 1. (a,b) A typical patient journey for a person with vitiligo in Latin America. (a) Depicts the journey to diagnosis. (b) Depicts the treatment journey. PCP: primary care physician; LA: Latin America; UV-NB: ultraviolet narrow band; PUVA: psoralen + ultraviolet A. +‘Healers,’ cosmetologists, pharmacists. *Vitamin D analogs, furocoumarins, antioxidants, topical JAK inhibitors. **Methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, JAK inhibitors. ***Antibiotics, antioxidants, vitamin supplements.

The first steps in comprehensive vitiligo management are stopping disease progression and stimulating and maintaining repigmentation. The melanocyte reservoirs play a fundamental role in these processes, which benefit from the opportune implementation of effective treatment. Access to vitiligo topical and systemic therapy varies across LA and is frequently limited. Out-of-pocket health spending ranges from 17 to 50%, averaging much higher than in most high-income countries (HIC), limiting chronic disease treatment initiation and maintenance (Citation38). According to our survey, 83% of dermatologists report they are unsatisfied with the treatment options for vitiligo available to their patients through public healthcare in LA. depicts vitiligo treatment access in 11 countries in LA. Because various factors determine access, a few peculiarities in the countries represented on this panel are discussed below.

Table 2. Access to vitiligo treatment as reported by dermatologists in LA.

Corticosteroids, both topical and systemic, are frequently used to treat vitiligo (Citation39–41). In Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, they are theoretically accessible through the public healthcare system. However, true access is restricted because medications are not always available for dispensing. Argentina has three insurance options, and access to public healthcare is also contingent on medication availability. Workers’ and private insurance cover 40% of treatment costs, leaving 60% paid out-of-pocket.

Calcineurin inhibitors and steroid-sparing agents, such as topical pimecrolimus (only available in Brazil and Mexico) and tacrolimus are important in vitiligo treatment protocols (Citation40,Citation42). Despite their high safety profile, they are not approved for this indication worldwide. They are not accessible through the public healthcare system in Brazil and Colombia. In Colombia, they can only be accessed through legal action (Citation43). In Mexico, they are authorized but not reimbursed by the national healthcare system. In Argentina, the situation described for corticosteroids applies to these medications as well.

Monobenzone is one of the only FDA-approved vitiligo treatment currently available globally, but it removes the remaining pigment to even skin color, which is not the desired effect for most patients, and its availability in LA is minimal (Citation44,Citation45). Recently, ruxolitinib was approved by the FDA as a depigmenting treatment for non-segmental vitiligo (Citation46).

27ch as methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine can also be indicated in extended and refractory diseases (Citation39,Citation47–50). In Brazil, they are available but not accessible through the public healthcare system for vitiligo. In Colombia, they are widely accessible through public healthcare. In Mexico and Argentina, they are available but not covered by the public healthcare system. In Argentina, work and private insurance cover 40% of the cost.

Phototherapy is an effective treatment method with limitations, such as cost, frequency, and the number of sessions required (Citation51–53). Phototherapy is accessible through the public healthcare system in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico. It is covered in Brazil for other dermatologic conditions but not for vitiligo. Notably, access to phototherapy devices is limited to major cities and specialized centers. In the absence of phototherapy medical devices, particularly in settings with limited resources, helio-therapy (controlled sun exposure) protocols may be a viable alternative. However, there is little evidence of its effectiveness; it must be regulated to prevent adverse side effects and is climate-dependent (Citation54).

JAK inhibitors are a promising novel vitiligo treatment. The IFN-γ-dependent cytokines produced in this pathway have been implicated in vitiligo’s pathogenesis, making it an attractive therapeutic target (Citation9). However, innovative pharmaceuticals face many challenges in LA. Innovative care is often seen as an expense rather than an investment, and most countries in LA lack adequate health technology assessments for value-based regulatory decisions (Citation9). As seen in , some countries have access to JAK inhibitors, but they are not approved for the indication of vitiligo and often require legal action to gain access.

Unmet needs assessment

Globally, vitiligo is a disease with myriad unmet needs. These include insufficient comprehensive diagnostic criteria, limited approved treatment options, and a scarcity of predictive markers or models. There is no definitive treatment, and more research into vitiligo’s pathophysiology is required, possibly leading to much-needed new therapies (Citation16,Citation55). Specific clinical definitions may enable researchers to define better patient sub-groups for research and clinical trials (e.g., immune or inflammatory vs. non-immune; halo nevus associated vs. non-halo nevus associated, etc.). In addition, neither tools nor criteria exist for an objective clinical evaluation of disease stability. Although there is a global need to fill the gaps mentioned above, this assessment focuses on the unmet needs of patients with vitiligo in LA.

Disease awareness among all stakeholders

There are myths, misconceptions, and misinformation about vitiligo among all stakeholders in LA. Vitiligo is frequently perceived as a cosmetic condition rather than a systemic disease, requiring dedicated medical care. Thus, many patients receive inadequate care or do not consult their healthcare providers. Most surveyed physicians report that vitiligo-related myths and misinformation (e.g., that it is contagious) lead to stigmatization and discrimination of affected patients (). Policymakers are generally unaware of the disease burden represented by vitiligo and the importance of ensuring timely access to specialized care and treatment.

Table 3. Vitiligo perception in LA.

Access to diagnosis

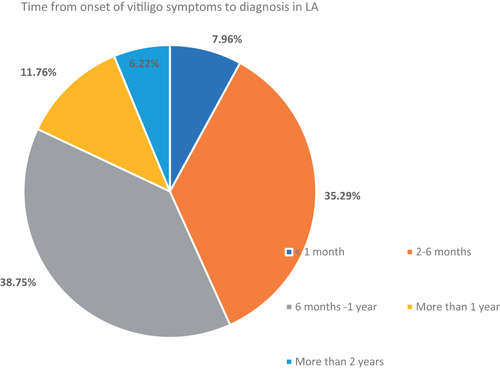

Globally, the average diagnostic delay for vitiligo is 3 years (Citation56). In tertiary care centers, delays ranged from 2.7 to 9.5 years in Brazil and from 1 month to 15 years in Mexico (Citation15,Citation17). 2-year diagnostic delays have been documented in Peru and Ecuador (Citation56,Citation57). Of the dermatologists surveyed, 56.7% reported a diagnostic delay of 6 months to 2 years, 35.3% estimated a delay of 2–6 months, and only 8% said patients achieved a diagnosis in <1 month ().

Access to specialists

There is a shortage of dermatologists in most LA countries. The recommended ratio of dermatologists is 4 per 100,000 inhabitants, which only Argentina (8.0) and Brazil (4.6) meet in LA (Citation58). Chile has 3.1, while Colombia, Mexico, and Peru have between 1.1 and 1.3 per 100,000 inhabitants (Citation59). Also, dermatologists are concentrated in major cities, leaving smaller cities and rural areas underserved. Access to high-quality healthcare services relies on a productive, well-distributed, and qualified healthcare workforce. Two-thirds of dermatologists polled said it took three months to one year for patients to see a dermatologist after receiving a referral ().

Figure 3. Typical period elapsed from referral to appointment with a dermatologist in Latin America.

Additionally, there are both insufficient training opportunities for new dermatologists and job opportunities in the public sector for these specialists. Furthermore, and possibly because of this, dermatologists in LA tend to be more inclined toward cosmetic surgery and private practice and frequently leave the region to work in HIC.

Access to treatment

As detailed in , access to vitiligo treatment in LA is limited. Fragmented care may also be detrimental to disease management because uninterrupted therapy (>2 years) has been shown to protect against recurrence (Citation60). In a retrospective single-center cohort study that examined treatment delay and its effect on vitiligo, patients with a mean 4.46-month treatment delay experienced disease progression (40.7%) and recurrence (32.1%) more frequently than patients treated more expediently, who experienced only 12.3% progression and 12.2% disease recurrence (Citation60). According to 84% of dermatologists surveyed, 50% of their patients might receive continuous therapy for more than two years (see ).

Physician training

Lack of training on vitiligo diagnosis and management at both the primary and specialized levels frequently contributes to delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation. Two-thirds of dermatologists surveyed reported that primary care providers (PCP) are not adequately trained to diagnose vitiligo, but most can recognize appropriate referral cases. At the specialist level, treatment is often unstandardized and based on experience, and comorbidities are not always addressed, possibly due to the lack of disease guidelines and clinical evidence (see ).

Table 4. Diagnosis and use of clinimetric tools for vitiligo in Latin America.

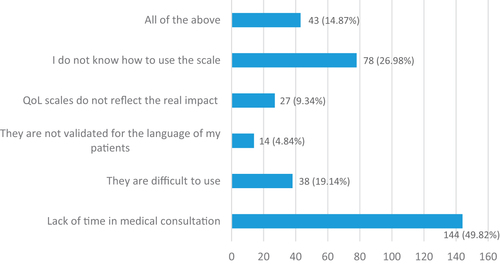

Use of clinimetric tools for disease severity and QoL assessment

About 75% of dermatologists stated they rarely or never use clinimetric instruments to assess QoL (DLQI and VitiQoL) in routine clinical practice, and 85.1% do not use these to establish disease severity (VES, VETF, VASI) (). Short time allocated for medical consults (49.8%), a lack of knowledge of how to use the tools (27%), and the fact that tools are challenging to use (19.14%) were the reasons most cited for the lack of utilization (). Additionally, not all tools are culturally and linguistically validated for usage in LA.

National or regional clinical practice guidelines (CPG)

Standardized vitiligo diagnosis and treatment recommendations are essential in improving patient outcomes. Currently, there are no national or regional CPG for vitiligo in LA. Some countries, such as Argentina (Citation61) and Brazil (Citation6) have developed consensus statements including recommendations, and occasionally European or United States guidelines are applied. However, the majority of treatment decisions are based on experience. The lack of CPG for vitiligo results in unstandardized care for patients with the same clinical condition, depending on their country, city, hospital, and physician.

Patient education

Misinformation is widespread regarding vitiligo. Some patients report not receiving adequate support from their physician (Citation16,Citation62) and frequently rely on untrustworthy non-medical sources for information (Citation63). This can result in potentially harmful treatments and medical care delays. Additional work is required to increase the availability of reliable vitiligo content (Citation64,Citation65). There is a need for healthcare systems, academic and medical associations, and PO to collaborate to develop credible instructional materials and opportunities.

Patient organizations/advocacy groups

This panel found no official patient organizations (PO) or advocacy groups for vitiligo operating in LA. POs that educate, advocate, and provide support services for patients and their caregivers can be powerful allies for people with vitiligo. Some diseases, like psoriasis and AD, have several PO that serves this function (Citation66). Similarly, vitiligo would benefit from the creation of these groups.

Regional data

Data-driven healthcare is propelling personalized medicine in HIC, leading to improved outcomes. There are insufficient data regarding vitiligo in LA in terms of epidemiology, patient outcomes, disease course, disease burden, and QoL effects. Increasing local data on vitiligo will benefit the patient and provide crucial insights into regional disease behavior.

Conclusions

Vitiligo is a severe, chronic skin disorder with systemic comorbidities that has numerous unmet needs globally and in LA. Patients face barriers owing to a lack of disease awareness and research, social ostracization, and limited treatment options. In addition to the medical and psychological difficulties associated with vitiligo, barriers in LA healthcare systems may negatively impact diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Access to timely diagnosis and treatment is crucial for improving outcomes.

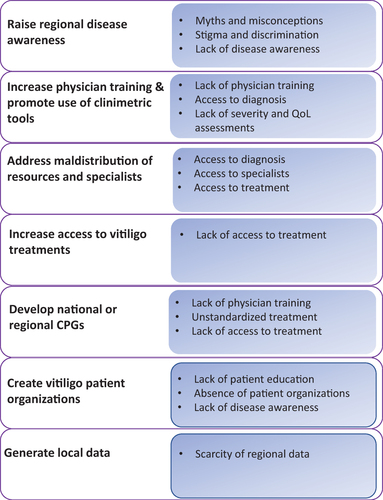

Below are recommendations to address the challenges identified in this review. For their implementation to be successful. all stakeholders must collaborate to coordinate efforts and find solutions, including governments, medical societies, academics, PO, industry, and the public. Of note, while these recommendations are tailored for the LA context, other middle and low-income regions may benefit from their implementation. A summary of the challenges and their corresponding recommendations can be seen in .

Limitations

This article has some limitations. First, not every country in Latin America is represented on the panel, which we tried to offset by including as many as possible in the survey. However, the views and situations of every country may not be evenly represented. Additionally, scarce previous research and literature conducted in Latin America on vitiligo limited the literature search and supporting data.

Ethical approval

This is a narrative review with no patient information.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Thais Vidal, BA, for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This is a narrative review, with results taken from the literature and professional experience of the panel. The data from the survey is available from the corresponding author.

Box 1. Recommendations to improve the landscape of vitiligo in Latin America.

CREATE REGIONAL DISEASE AWARENESS

Recognize vitiligo as a high-impact chronic and systemic disease requiring dermatological management and multidisciplinary care for psychosocial consequences and comorbidities.

Develop widespread awareness campaigns to educate the public on the non-contagious nature of the condition, advocate inclusivity, and fight discrimination and stigmatization. Videos, disease days, celebrities, and social media are examples.

INCREASE PHYSICIAN TRAINING

Primary Care Level (PCPs and pediatricians)

^ Recognize vitiligo and be aware of possible comorbidities

^ Recognize appropriate referral situations and understand the importance of referring to a dermatologist to decrease diagnostic delays and allow for early intervention

^ Dispel misconceptions surrounding vitiligo, including that it is untreatable

Dermatologists

^ Obtain a complete medical history and classify the disease based on its clinical characteristics (Citation7)

^ Carry out a differential diagnosis from other entities that lead to hypopigmentation (Citation8)

^ Actively investigate mental health impact and other comorbidities to involve the necessary specialists to provide a holistic approach posteriorly

^ Use clinimetric instruments to assess the impact on QoL and disease severity, as they allow objectivity in evaluating progression and treatment response. Using apps available for mobile phones may facilitate the use of these tools

^ Ensure adequate follow-up and reevaluation of disease progression and impact on QoL continuously throughout the disease course to guide treatment decisions

^ Provide comprehensive education to patients and caregivers on the disease course, proper care, and preventive measures, and create realistic treatment expectations.

ADDRESS MALDISTRIBUTION OF RESOURCES AND SPECIALISTS

Create job opportunities for dermatologists within public healthcare systems and provide incentives to work in non-central cities in need of specialists

Teledermatology can be implemented as a tool to increase access to specialized care in distant and rural areas when in-person visits are not an option (Citation62,Citation63). It can potentially be a tool for the early detection and intervention of vitiligo (Citation9)

Increase local training opportunities for aspiring dermatologists

INCREASE ACCESS TO VITILIGO MANAGEMENT

Ensure continuous access to multidisciplinary care and follow-up

Ensure continuous access and reimbursement of indicated treatments, psychosocial support, and complementary measures

DEVELOP NATIONAL OR REGIONAL CPG

Develop CPG for vitiligo to promote evidence-based and standardized care through collaboration between medical societies, government, and academia. If this is not possible in the short-to-medium term, each country’s leading medical society should recommend an international guideline to adopt.

CREATE PATIENT ORGANIZATIONS

Create an official PO dedicated to advocating for vitiligo to be recognized as a chronic disease, providing peer support, informing, and advising its members on disease-related issues, advocating for treatment approvals and reimbursement, and sensitizing society on the

GENERATE LOCAL DATA

Encourage local and regional research regarding vitiligo epidemiology, patient outcomes, disease course, disease burden, impact on QoL, and genetic, environmental, and immunologic dynamics.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chang WL, Lee WR, Kuo YC, et al. Vitiligo: an autoimmune skin disease and its immunomodulatory therapeutic intervention. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:797026.

- Lotti T, D'Erme AM. Vitiligo as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(3):430–434.

- Dahir AM, Thomsen SF. Comorbidities in vitiligo: comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(10):1157–1164.

- De Resende Silva CM, Baptista Pereira L, Gontijo B, et al. Childhood vitiligo: clinical and epidemiological characteristics. An Brasil Dermatol. 2022;82(1):47–51.

- Ezzedine K, Grimes PE, Meurant JM, et al. Living with vitiligo: results from a national survey indicate differences between skin phototypes. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(2):607–609.

- Dellatorre G, Antelo DAP, Bedrikow RB, et al. Consensus on the treatment of vitiligo – Brazilian society of dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):70–82.

- Ezzedine K, Lim HW, Suzuki T, et al. Revised classification/nomenclature of vitiligo and related issues: the vitiligo global issues consensus conference. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25(3):E1–E13.

- Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: a review. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):571–592.

- Eleftheriadou V, Atkar R, Batchelor J, et al. British association of dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with vitiligo 2021. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(1):18–29.

- Gandhi K, Ezzedine K, Anastassopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(1):43–50.

- Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. Introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):473–491.

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(10):1206–1212.

- Zhang Y, Cai Y, Shi M, et al. The prevalence of vitiligo: a meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(9):e0163806.

- Estrada Castañón R, Torres Bibiano B, Alarcón Hernández H, et al. Epidemiología cutánea en dos sectores de atención médica en Guerrero, México. Dermatol Rev Mex. 1992;26:6.

- Martins C, Hertz A, Luzio P, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of childhood vitiligo: a study of 701 patients from Brazil. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(2):236–244.

- Elbuluk N, Ezzedine K. Quality of life, burden of disease, co-morbidities, and systemic effects in vitiligo patients. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(2):117–128.

- Morales-Sánchez MA, Vargas-Salinas M, Peralta-Pedrero ML, et al. Impact of vitiligo on quality of life. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(7):637–642.

- Spritz RA, Andersen GHL. Genetics of vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(2):245–255.

- Nath SK, Majumder PP, Nordlund JJ. Genetic epidemiology of vitiligo: multilocus recessivity cross-validated. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(5):981–990.

- Mahajan VK, Verma YR, Mehta KS, et al. Adults with a more extensive body involvement, moderate to extremely severe vitiligo and a prolonged clinical course have an early onset in childhood in addition to other prognostic factors as compared to individuals with later-onset vitiligo. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62(1):e24–e28.

- Barona MI, Arrunátegui A, Falabella R, et al. An epidemiologic case-control study in a population with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(4):621–625.

- Verma D, Hussain K, Namiq KS, et al. Vitiligo: the association with metabolic syndrome and the role of simvastatin as an immunomodulator. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e14029.

- Manzoni A, Weber MB, Nagatomi ARDS, et al. Assessing depression and anxiety in the caregivers of pediatric patients with chronic skin disorders. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6):894–899.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(6):757–774.

- Porter J, Beuf A, Nordlund JJ, et al. Personal responses of patients to vitiligo: the importance of the patient-physician interaction. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(9):1384–1385.

- Parsad D, Dogra S, Kanwar A. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):58.

- Morrison B, Burden-Teh E, Batchelor JM, et al. Quality of life in people with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(6):e338–e339.

- Brown MM, Chamlin SL, Smidt AC. Quality of life in pediatric dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(2):211–221.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(3):309–318.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo e emoções. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84(1):41–45.

- Sukan M, Maner F. The problems in sexual functions of vitiligo and chronic urticaria patients. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33(1):55–64.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(2):159–164.

- Catucci Boza J, Giongo N, Machado P, et al. Quality of life impairment in children and adults with vitiligo: a cross-sectional study based on dermatology-specific and disease-specific quality of life instruments. Dermatology. 2016;232(5):619–625.

- Laverde-Walter A, Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-Garcia AM, et al. Quality of life in a Colombian cohort of patients with vitiligo. Mex J Dermatol. 2020;64(3):7.

- Peralta-Pedrero ML, Morales-Sánchez MA, Jurado-Santa Cruz F, et al. Systematic review of clinimetric instruments to determine the severity of non-segmental vitiligo. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(3):e178–e185.

- Basra MK, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The family dermatology life quality index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):528–538.

- Basra MK, Edmunds O, Salek MS, et al. Measurement of family impact of skin disease: further validation of the family dermatology life quality index (FDLQI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(7):813–821.

- OECD, Bank TW. Health at a glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020; 2020.

- Singh H, Kumaran MS, Bains A, et al. A randomized comparative study of oral corticosteroid minipulse and low-dose oral methotrexate in the treatment of unstable vitiligo. Dermatology. 2015;231(3):286–290.

- Gawkrodger DJ, Ormerod AD, Shaw L, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):1051–1076.

- Ezzedine K, Whitton M, Pinart M. Interventions for vitiligo. Jama. 2016;316(16):1708–1709.

- Cavalié M, Ezzedine K, Fontas E, et al. Maintenance therapy of adult vitiligo with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):970–974.

- Feltes RF, Sendagorta E, Ramírez P, et al. Treatment during a year with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment in young patients with vitiligo. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cir Dermatol. 2019;19(1):7.

- Njoo MD, Vodegel RM, Westerhof W. Depigmentation therapy in vitiligo universalis with topical 4-methoxyphenol and the Q-switched ruby laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(5 Pt 1):760–769.

- Mosher DB, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB. Monobenzylether of hydroquinone. A retrospective study of treatment of 18 vitiligo patients and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97(6):669–679.

- Sheikh A, Rafique W, Owais R, et al. FDA approves ruxolitinib (opzelura) for vitiligo therapy: a breakthrough in the field of dermatology. Ann Med Surg. 2022;81:104499.

- Radmanesh M, Saedi K. The efficacy of combined PUVA and low-dose azathioprine for early and enhanced repigmentation in vitiligo patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(3):151–153.

- Mehta H, Kumar S, Parsad D, et al. Oral cyclosporine is effective in stabilizing active vitiligo: results of a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5):e15033.

- ElGhareeb MI, Metwalli M, AbdelMoneim N. Combination of oral methotrexate and oral mini-pulse dexamethasone vs either agent alone in vitiligo treatment with follow up by dermoscope. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13586.

- Taneja AK, Vyas K, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in treatment of progressive vitiligo: an open-label, single-arm interventional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:3.

- Bossert T, Blanchet N, Suzanne S, Bank I-AD, et al. Comparative review of health system integration in selected countries in Latin America. In: Social protection and health division. Inter-American Development Bank; 2014. Available from: https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/11898/comparative-review-health-system-integration-selected-countries-latin-america

- Brazzelli V, Antoninetti M, Palazzini S, et al. Critical evaluation of the variants influencing the clinical response of vitiligo: study of 60 cases treated with ultraviolet B narrow-band phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(10):1369–1374.

- Vélez NG, Bohórquez L, Montes AM, et al. Phototherapy and other therapeutic alternatives for vitiligo treatment, ten years of experience in phototherapy service of the dermatology center of universidad CES. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cir Dermatol. 2019;18(3):10.

- Horio T. Skin disorders that improve by exposure to sunlight. Clin Dermatol. 1998;16(1):59–65.

- Boniface K, Taïeb A, Seneschal J. New insights into immune mechanisms of vitiligo. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151(1):44–54.

- Valverde J. Vitiligo: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Folia Dermatol. 2007;18(1):5.

- Aguayo L. Sociedad Peruana de Dermatología editores. II Reunión de Sociedades Latinoamericanas de Dermatología y VII Congreso Peruano de Dermatología. Lima: Revista de la Sociedad Peruana de Dermatología; 1998. (Association P, editor. Vitiligo).

- Borzutzky A, Larco JI, Luna PC, et al. Atopic dermatitis in Latin America: a roadmap to address data collection, knowledge gaps, and challenges. Dermatitis. 2022;33(6S):S83–S91.

- Avellaneda CF, Seidel A, Londono A, et al. Social, economic, geographic and occupational characterization of dermatologists in Colombia. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cir Dematol. 2012;20(2):129–133.

- Xu X, Zhang C, Jiang M, et al. Impact of treatment delays on vitiligo during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a retrospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(4):e15014.

- Molé M, Coringrato M. Update on vitiligo. Argentina Dermatol. 2019;25(2):5.

- Porter J, Beuf AH, Lerner A, et al. Response to cosmetic disfigurement: patients with vitiligo. Cutis. 1987;39(6):493–494.

- Talsania N, Lamb B, Bewley A. Vitiligo is more than skin deep: a survey of members of the vitiligo society. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(7):736–739.

- Read C, Wu KK, Young PM, et al. Vitiligo health education: a study of accuracy and engagement of online educational materials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(6):623–629.

- Chu H, Lee JW, Lee YI, et al. Delayed treatment of generalized morphea due to misdiagnosis as vitiligo at an oriental medical clinic. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(5):649–650.

- Sánchez J, Ale IS, Angles MV, et al. Healthcare disparities in atopic dermatitis in Latin America: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022; 1–18. DOI:10.1007/s13555-022-00875-y