Abstract

Background

Data from the Japanese phase 3 Nemolizumab-JP01 study (JapicCTI-173740) found that nemolizumab in combination with topical treatments reduced pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled with current therapies.

Methods

This post-hoc analysis examined associations between improvements in pruritus (visual analog scale [VAS]) and eczema (Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI]), and achievement of other clinically relevant endpoints including the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).

Results

Pruritus VAS responders (≥50% improvement from baseline to week 16) showed greater improvements from baseline in these additional endpoints as early as week 1, compared with non-responders. Responders also had EASI improvement, and more than 80% achieved an ISI score ≤7, or had improvement in the DLQI or POEM. The percent change from baseline in VAS and EASI scores at week 16 was in favor of nemolizumab in all subgroups based on baseline characteristics. No specific factor affecting treatment response to nemolizumab was identified.

Conclusions

In this post-hoc analysis, nemolizumab-treated patients who had greater pruritus reductions also showed improvements in other eczema symptoms; pruritus alleviation appeared to be responsible for the improvements in eczema, sleep and daily life.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with pruritus, which may exhibit repeated exacerbation and remission (Citation1). Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 8% of adults and 20% of children may be affected (Citation2), and a recent systematic literature review reported that the prevalence of atopic dermatitis is rising in individuals of East Asian ethnicity (Citation3).

The symptoms of atopic dermatitis, and their effects on patients, are diverse (Citation4), and individualized treatment selection is necessary, based on the patient’s medical presentation and psychosocial and emotional needs. Notably, in some patients with atopic dermatitis, the burden of illness is great even if the cutaneous signs are considered to be mild (Citation5). In a recent real-world, observational cohort analysis conducted in 171 patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, it was noted that subjective perceptions of disease severity were the most significant predictors of quality of life (QOL) scores, and were independent of objective clinical scoring systems (Citation6).

One of the fundamental characteristics of atopic dermatitis is pruritus, which has a particularly negative impact on patient well-being and is known to impair QOL (Citation7–10). There is considerable evidence to suggest that the inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-31 plays a key immunopathologic role in pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis (Citation11,Citation12), and that it affects inflammatory response and epidermal-barrier disruption in atopic dermatitis (Citation11,Citation13). Nemolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-31 receptor A (Citation14,Citation15), reduced pruritus and skin inflammation compared with placebo in global phase 2 and phase 3 studies in a Japanese population, with these improvements maintained for up to 68 weeks (Citation16–20). Data from the Japanese 16-week, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase 3 Nemolizumab-JP01 study found that 60 mg nemolizumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in combination with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors (TCS/TCI) resulted in a greater reduction in pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis and in an improvement in cutaneous signs, compared with placebo plus topical agents (Citation20). In all studies conducted to date, both in global and in Japanese-only populations, nemolizumab was found to have a favorable, consistent safety profile.

It is generally considered that treatment effectiveness should be evaluated using multiple criteria, including QOL and the effect on daily life, in addition to eczema or itch (Citation21). Additionally at present, there is a lack of information to guide patient selection for the proper usage of nemolizumab or to predict efficacy. In this post-hoc analysis, we conducted a responder analysis to examine the association between improvements in pruritus (using the pruritus visual analog scale [VAS] (Citation22)) and eczema (using the Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI] (Citation23)) with achievement of other clinically relevant endpoints, including patient-reported sleep outcomes and QOL, using data from the 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the Nemolizumab-JP01 study. We also analyzed the outcome data based on patient baseline demographic and clinical characteristics to determine whether there were any predictors of response which might impact patient selection.

Methods

Study design, patients, and treatment

The Nemolizumab-JP01 study was a Japanese phase 3, multi-center clinical trial which included a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group superiority analysis of nemolizumab vs placebo (Part A) and a 52-week, open-label, long-term follow-on study (Part B). The study was registered with the Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center-Clinical Trials Identifier JapicCTI-173740, and was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all other applicable regulatory and legal requirements. All subjects (or their legal guardian) provided written informed consent prior to initiation of any study procedures. The institutional review boards at each participating study center approved the protocol and all other study-related documentation.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published elsewhere (Citation20). In brief, patients aged ≥13 years with pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis, which was inadequately controlled with currently available therapies, were eligible for enrollment into the trial. Eligible patients were required to have inadequate pruritic response to medium-potency TCS or TCI administered at a stable dose for at least 4 weeks and to oral antihistamines administered at a stable dose for at least 2 weeks (or an inability to receive such therapies), where an inadequate pruritic response was defined as a score of ≥3 on a five-level itch scale (range 0–4; higher scores indicate worse itching (Citation24)). Additional eligibility criteria were a pruritus VAS score (range 0–100; higher scores indicate worse pruritus) of 50 or more on the day of randomization, and an EASI score (range 0–72; higher scores indicate greater severity) of 10 or more on the day of randomization.

During Part A of the study, patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio (via an interactive web response system) to receive subcutaneous nemolizumab 60 mg or placebo every 4 weeks. Concurrent medications prescribed for atopic dermatitis (TCS, TCI, oral antihistamines, and antiallergics) were required to remain unchanged throughout Part A.

Study outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint of the Nemolizumab-JP01 study was the percent change in the weekly mean pruritus VAS score from baseline to week 16. Scores were evaluated by patients daily and recorded in an electronic diary provided by the sponsor; weekly mean scores were calculated by averaging daily scores. The primary and secondary outcomes from Part A have been published elsewhere (Citation20); here, we report post-hoc analyses using data from Part A.

Patients were divided into responder and non-responder groups. Responders were defined as those who achieved an improvement of ≥50% from baseline at week 16 for VAS or EASI (VAS responder or EASI responder, respectively). Those who did not fall under responder criteria were defined as non-responders (VAS non-responder or EASI non-responder, respectively). Based on the primary analysis, the mean percentage change in the VAS and EASI scores in the nemolizumab treatment group were −42.8% and −45.9%, respectively (Citation20); thus, a responder threshold of 50% was set to ensure a sufficient number of evaluable patients in each responder/non-responder group.

Clinical and patient-reported outcomes included the pruritus numerical rating scale (NRS; range 0–10; higher scores indicate worse pruritus (Citation25)), the static investigator’s global assessment scale (sIGA; range 0–5; higher scores indicate greater severity of atopic dermatitis (Citation26)), the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; range 0–28; higher scores indicate greater severity (Citation27)), the DLQI (range 0–30; higher scores indicate a greater effect on daily life (Citation28)), and the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM; range 0–28; higher scores indicate greater severity (Citation29)). The proportions of VAS and EASI responders and non-responders who achieved the following clinical response thresholds were compared: a VAS score <30 mm (the cutoff value delineating mild pruritus (Citation30)), improvement of at least 4 points on the NRS (considered to be the minimal clinically important difference [MCID] (Citation25)), achievement of a 5-level itch score ≤1, achievement of an EASI total score ≤7, improvement of at least 50% or 75% in the EASI total score, improvement of ≥2 levels to achieve a final score of ≤1 in the sIGA, achievement of an ISI score of <7, improvement of at least 6 points (the MCID (Citation31)) in the ISI score, achievement of a DLQI score of ≤4 (based on a previously defined cutoff value (Citation32)), improvement of at least 4 points (the MCID (Citation33)) in the DLQI score, and improvement of at least 4 points (the MCID (Citation34)) in the POEM score.

In a subgroup analysis according to patient baseline characteristics, the percent change from baseline to week 16 in the VAS score and the EASI score was calculated, and differences were evaluated between treatment and placebo groups. The baseline factors evaluated included demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, weight), and clinical status (e.g., duration of atopic dermatitis, VAS score, EASI score, 5-level itch score). For the EASI score, the intensity of each of four symptoms (erythema, induration/papulation, excoriation, lichenification) was calculated respectively as the sum of the four body sites (head and neck, trunk, upper limbs, and lower limbs) scores divided by 4.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of nemolizumab-treated patients meeting the thresholds for the other outcomes were reported as n (%) for VAS responders/non-responders and EASI responders/non-responders. Patients who withdrew or received rescue medication (higher-potency topical glucocorticoids, at the investigator’s discretion, when worsening atopic dermatitis-associated eczema was noted) were counted as non-responders at week 16.

The subgroup analysis of percent change from baseline in VAS and EASI scores according to baseline characteristic was conducted using the modified intention-to-treat analysis set. Missing values at week 16 were imputed using last observation carried forward (LOCF) methodology. For evaluations of VAS scores, data from patients who received rescue therapy due to exacerbations of atopic dermatitis were considered missing from the time of use and imputed by LOCF. Based on the data from the initial Part A analysis (Citation20), we considered that the impact of rescue therapy on the EASI score was very small; thus, for evaluation of EASI, data after receipt of rescue therapy were included in the analysis. The least squares (LS) mean (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) were calculated for each subgroup category using analysis of covariance using the administration group, the subgroup item, and the interaction term with the subgroup item × administration group as the fixed effects. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) 9.3 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Responder and non-responder analysis in nemolizumab-treated patients

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by responder status

As previously reported, 143 Japanese patients were randomly assigned to receive nemolizumab and 72 to receive placebo in Part A of the Nemolizumab-JP01 study (Citation20). Patient baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were generally similar between the nemolizumab and placebo treatment groups (). Distributions of baseline factors in nemolizumab-treated patients according to responder/non-responder status are also reported in . Although many factors did not markedly vary by response status, it was observed that pruritus VAS responders were more likely to have an EASI erythema score of ≥2, an EASI induration/papulation score of ≥2, and ≥20 pruriginous lesions and papules, compared with non-responders.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in the modified intention-to-treat population, and by respondera subgroups in the nemolizumab treatment group.

Clinically meaningful improvements by responder status

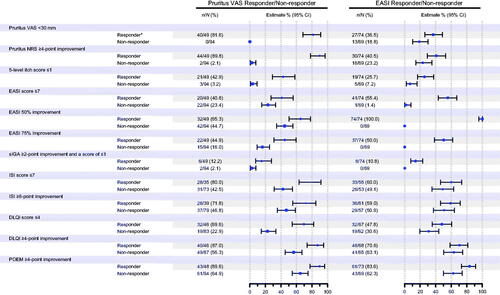

In the analysis of the association between improvements in pruritus and eczema with achievement of other clinically relevant endpoints in the nemolizumab-treated VAS responders and EASI responders, more responders than non-responders experienced clinically meaningful improvements from baseline in atopic dermatitis signs, symptoms, or QOL at week 16 ().

Figure 1. Subgroup analysis (analysis of covariance) for percent change from baseline at week 16 in pruritus visual analog scale (VAS) and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) responders (nemolizumab treatment group). *Responder was defined as those who achieved an improvement of ≥50% from baseline at week 16 for either VAS or EASI. CI: confidence interval; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; NRS: numerical rating scale; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; sIGA: static Investigator’s Global Assessment.

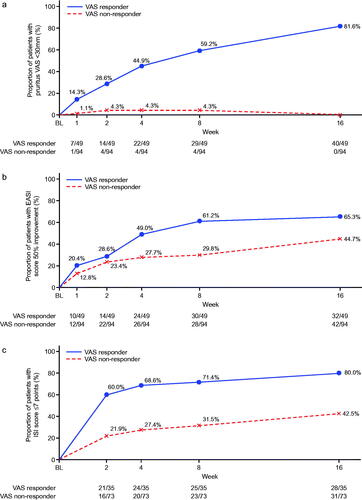

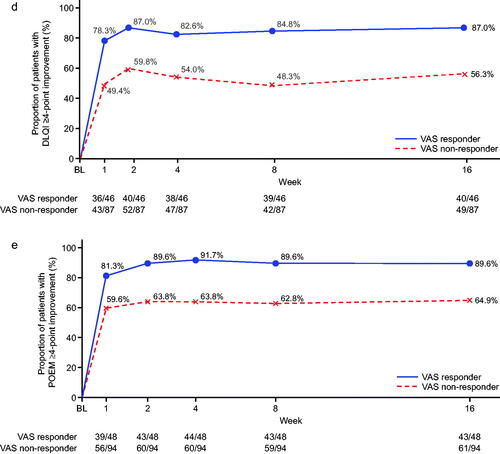

Changes over time in outcomes according to VAS response are shown in . In addition to improvements in pruritus VAS (to <30 mm), improvements in dermatitis were also observed within the group of VAS responders. In total, 65.3% of patients in the VAS responders achieved an improvement in EASI score of ≥50% from baseline to week 16. The mean percent change in EASI from baseline to week 16 was −60.7% among the VAS responders. Moreover, from the earliest weekly timepoint evaluated, VAS responders were more likely to achieve the specified clinical response thresholds of ISI score of ≤7, DLQI improvement of ≥4 points, or POEM improvement of ≥4 points. By week 16, >80% of VAS responders had achieved ISI ≤7 and approximately 90% had POEM improvement of ≥4 points, and DLQI improvement of ≥4 points.

Figure 2. Time course of changes according to pruritus visual analog scale (VAS) response or non-response (nemolizumab treatment group). (a) Patients with pruritus VAS <30 mm; (b) patients with ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, analysis for this end point was performed only for patients with total insomnia severity index (ISI) score ≥6 at baseline; (c) patients with Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) ≤7 points, analysis for this end point was performed only for patients with a DLQI score of 4 or more at baseline; (d) patients with ≥4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); (e) patients with ≥4-point improvement in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). BL: baseline.

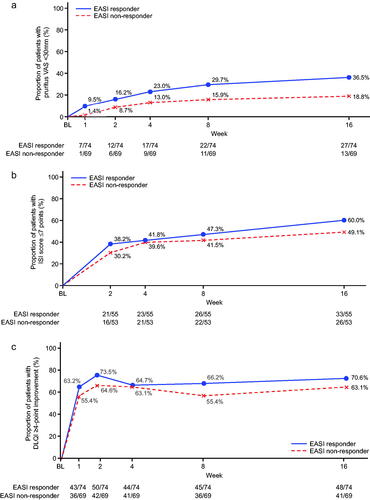

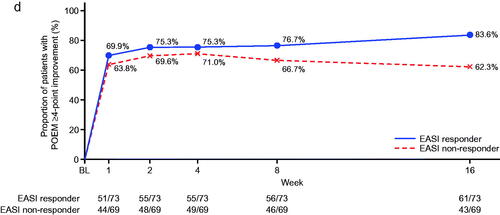

In terms of EASI responders, around 70% had a DLQI improvement of ≥4 points and >80% had a POEM improvement of ≥4 points by week 16 (). When evaluated over time, between-group differences for EASI responders and non-responders showed a tendency to be less pronounced () compared with the VAS responders/non-responders (); however, the lack of formal statistical comparison between VAS and EASI response groups precludes a definitive statement of disparity.

Figure 3. Time course of changes according to Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) response or non-response (nemolizumab treatment group). (a) Patients with pruritus visual analog scale (VAS) <30 mm; (b) patients with Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) ≤7 points, analysis for this end point was performed only for patients with total insomnia severity index (ISI) score ≥6 at baseline; (c) patients with ≥4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), analysis for this end point was performed only for patients with a DLQI score of 4 or more at baseline; (d) patients with ≥4-point improvement in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). BL: baseline.

Subgroup analysis based on patient baseline factors

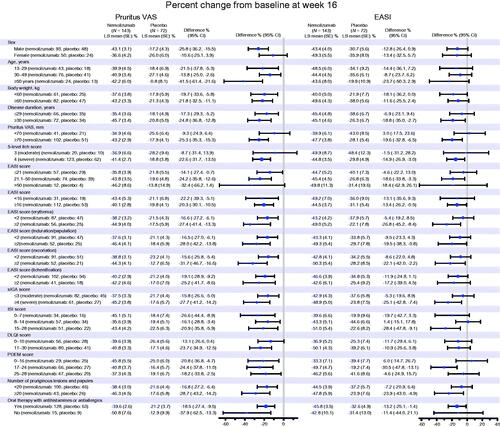

For the overall population, the LS mean percent change from baseline at week 16 in the pruritus VAS score was −42.8% in the nemolizumab group and −21.4% in the placebo group, and in the EASI score was −45.9% in the nemolizumab group and −33.2% in the placebo group (Citation20). The percent change from baseline in VAS and EASI scores at week 16 in each subgroup evaluated is shown in . The efficacy of nemolizumab to alleviate both pruritus and the signs and symptoms of AD was demonstrated in each subgroup. There appeared to be a tendency for patients with more severe AD (in terms of pruritus or the signs and symptoms of AD) to obtain greater reductions in the pruritus VAS and EASI scores, but there were no statistically observable differences.

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis (analysis of covariance) for percent change from baseline at week 16 in pruritus visual analog scale (VAS) and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores (modified intention-to-treat population). CI: confidence interval; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; LS: least squares; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; SE: standard error; sIGA: static Investigator’s Global Assessment.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of nemolizumab-treated patients from the Nemolizumab-JP01 study according to VAS and EASI responder status, we observed that VAS responders were more likely to demonstrate clinically important improvements in other pruritus indices (including VAS <30 mm, pruritus NRS improvement of ≥4, and 5-level itch score of ≤1), cutaneous signs (EASI improvement of ≥50%), and QOL scores. Interestingly, the proportions of patients achieving an improvement in the EASI score of ≥50% was similar between VAS responders and VAS non-responders until week 2; however, from week 4, the subgroups rapidly diverged, with a greater proportion observed in the VAS responder subgroup. We also observed greater improvements in QOL scores from baseline as early as week 1 in VAS responders compared with non-responders. In this analysis, more than 80% of pruritus VAS responders also showed improvement in sleep (which is often disturbed by itching (Citation35,Citation36)), in parameters of daily living, and in the self-assessment of atopic dermatitis. Thus, the early and sustained reduction of pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis is essential for other aspects of AD patient symptoms and signs. In addition, we observed that EASI responders demonstrated improvements in QOL (specifically, DLQI and POEM scores). Overall, these findings from the first analysis indicate that nemolizumab clears both pruritus and skin lesions, helping to reduce inflammation and break the itch-scratch cycle. Both of these contribute to further cutaneous improvements, fewer eruptions, and improved QOL at an early stage.

In the second analysis, of outcomes according to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, we found that treatment with nemolizumab 60 mg every 4 weeks plus topical TCS/TCIs showed similar efficacy on both pruritus and the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis, regardless of baseline severity (from moderate to severe), sex, or age. Although we did not identify specific predictive markers, one inference from our analysis is that factors such as sex, age, weight, and disease duration do not lessen the effectiveness of nemolizumab treatment, which opens up the option of treatment to a large swathe of affected patients with AD. Thus, further investigation will be required to assist in patient selection and ensure the optimal usage of nemolizumab.

The data from previous clinical studies have clearly demonstrated the anti-pruritic effects of nemolizumab plus topical treatments, while the current analyses confirm that patients can also obtain additional benefits in terms of improved eczema, sleep, and QOL. Notably, our results indicating improvements in QOL in treatment responders (i.e., those patients in whom pruritus and skin lesions were controlled) are aligned with a recent real-world report, in which the authors reported statistically significant correlations between DLQI scores and levels of patient-reported pruritus and sleep disturbance in 356 patients with atopic dermatitis who were treated with dupilumab (Citation37). Although the mechanisms of action and prescribing indications of nemolizumab and dupilumab differ, it seems clear that by treating pruritus, patients with atopic dermatitis gain considerable benefits in daily life quality. Given that subjective perceptions of their condition can add considerably to the overall patient burden (Citation6), treatments that improve both subjective and objective measures of atopic dermatitis are likely to play a crucial role in the effective management of patients. The wide-ranging impacts associated with amelioration of pruritus which were observed in the current analysis are likely to be a great respite for patients who have been unable to achieve sufficient relief with other treatments. We consider that the statistical analysis process conducted herein, and the results obtained, add substantial value to the breadth of knowledge relating to nemolizumab and more clearly underline the rationale for its use to treat pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis.

The major limitation of this analysis is the non-prespecified and post-hoc design. The study population was small, and the analysis was not specifically powered to calculate statistical differences for these exploratory analyses; the results must be considered accordingly. In addition, only data up to 16 weeks were evaluated, and long-term analyses will be necessary to confirm the longitudinal benefit of nemolizumab to treat this chronic condition.

Conclusions

In this post-hoc analysis, Japanese patients with greater pruritus reductions after administration of nemolizumab 60 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks showed clinically meaningful improvements in other inflammatory symptoms, sleep quality, and QOL. The reduction of pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis was confirmed to be important for other aspects of patient health. Subgroup analysis showed that baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of atopic dermatitis did not lessen the effectiveness of nemolizumab treatment in terms of both pruritus and the signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hiroshi Komazaki (Department of Clinical Development, Maruho, Kyoto) for assistance with the statistical analyses. The authors also wish to acknowledge editorial assistance provided by Sally-Anne Mitchell, Ph.D. and publication management provided by Hisanori Yoshida (both of McCANN HEALTH CMC, Japan), funded by Maruho Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan.

Disclosure statement

Kenji Kabashima has received grants from Japan Tobacco Inc., Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, ONO PHARMACEUTICAL, POLA PHARMA, TAIHO PHARMA, Torii Pharmaceutical, and The Procter & Gamble Company, and has received personal fees from Maruho. Takayo Matsumura and Yoshiteru Hayakawa are employees of Maruho. Makoto Kawashima has received personal fees from Maruho.

Data availability statement

The authors are unable to provide individual patient data as consent for distribution of personal information was not obtained in the clinical trial.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657–682.

- Cheng J, Wu JJ, Han G. Epidemiology and characterization of atopic dermatitis in East Asian populations: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(3):707–717.

- Luger T, Amagai M, Dreno B, et al. Atopic dermatitis: role of the skin barrier, environment, microbiome, and therapeutic agents. J Dermatol Sci. 2021;102(3):142–157.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Gadkari A, et al. Burden of illness in adults with atopic dermatitis: analysis of national health and wellness survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):187–195.

- Miniotti M, Lazzarin G, Ortoncelli M, et al. Impact on health-related quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression after 32 weeks of dupilumab treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(5):e15407.

- Legat FJ. Itch in atopic dermatitis – What is new? Front Med. 2021;8:644760.

- Bridgman AC, Block JK, Drucker AM. The multidimensional burden of atopic dermatitis: an update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(6):603–606.

- Chrostowska-Plak D, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Relationship between itch and psychological status of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(2):e239–e242.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340–347.

- Kabashima K, Irie H. Interleukin-31 as a clinical target for pruritus treatment. Front Med. 2021;8:638325.

- Saleem MD, Oussedik E, D'Amber V, et al. Interleukin-31 pathway and its role in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(7):591–599.

- Cornelissen C, Marquardt Y, Czaja K, et al. IL-31 regulates differentiation and filaggrin expression in human organotypic skin models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):426–433.

- Nemoto O, Furue M, Nakagawa H, et al. The first trial of CIM331, a humanized antihuman interleukin-31 receptor a antibody, in healthy volunteers and patients with atopic dermatitis to evaluate safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of a single dose in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(2):296–304.

- Oyama S, Kitamura H, Kuramochi T, et al. Cynomolgus monkey model of interleukin-31-induced scratching depicts blockade of human interleukin-31 receptor a by a humanized monoclonal antibody. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(1):14–21.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti-interleukin-31 receptor a antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):826–835.

- Silverberg JI, Pinter A, Pulka G, et al. Phase 2b randomized study of nemolizumab in adults with moderate-severe atopic dermatitis and severe pruritus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):173–182.

- Kabashima K, Furue M, Hanifin JM, et al. Nemolizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: randomized, phase II, long-term extension study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(4):1121.e7–1130.e7.

- Kabashima K, Matsumura T, Komazaki H, et al. Nemolizumab plus topical agents in patients with atopic dermatitis and moderate-to-severe pruritus provide improvement in pruritus and signs of atopic dermatitis for up to 68 weeks: results from two phase III, long-term studies. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(4):642–651.

- Kabashima K, Matsumura T, Komazaki H, et al. Trial of nemolizumab and topical agents for atopic dermatitis with pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):141–150.

- Di Agosta E, Salvati L, Corazza M, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic and immunologic skin diseases: in the eye of the beholder. Clin Mol Allergy. 2021;19(1):26.

- Reich A, Heisig M, Phan NQ, et al. Visual analogue scale: evaluation of the instrument for the assessment of pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(5):497–501.

- Barbier N, Paul C, Luger T, et al. Validation of the eczema area and severity index for atopic dermatitis in a cohort of 1550 patients from the pimecrolimus cream 1% randomized controlled clinical trials programme. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(1):96–102.

- Kawashima M, Nakagawa H. Olopatadine hydrochloride in children: evidenced efficacy and safety for atopic dermatitis treatment in a randomized, multicentre, double-blind, parallel group comparative study. Nishinihon J Dermatol. 2011;73:278–289.

- Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, et al. Peak pruritus numerical rating scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):761–769.

- Schmitt J, Langan S, Williams HC. What are the best outcome measurements for atopic eczema? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1389–1398.

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, et al. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. May 1

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(12):1513–1519.

- Kido-Nakahara M, Katoh N, Saeki H, et al. Comparative cut-off value setting of pruritus intensity in visual analogue scale and verbal rating scale. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):345–346.

- Yang M, Morin CM, Schaefer K, et al. Interpreting score differences in the insomnia severity index: using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(10):2487–2494.

- Nast A, Boehncke WH, Mrowietz U, et al. S3 – Guidelines on the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris (English version). Update. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(Suppl 2):S1–S95.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33.

- Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MM, et al. EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67(1):99–106.

- Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis: a 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(4):1033–1040.

- Ramirez FD, Chen S, Langan SM, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(5):e190025.

- Mastorino L, Rosset F, Gelato F, et al. Chronic pruritus in atopic patients treated with dupilumab: real life response and related parameters in 354 patients. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(7):883.