?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Introduction

Treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) include excision (surgical removal) and destruction (cryotherapy or curettage with or without electrodesiccation) in addition to other methods. Although cure rates are similar between excision and destruction for low-risk NMSCs, excision is substantially more expensive. Performing destruction when appropriate can reduce costs while providing comparable cure rate and cosmesis.

Objective

To identify characteristics associated with exclusive (outlier) performance of excision or destruction for NMSC.

Methods

The study consisted of malignant excision and destruction procedures submitted by dermatologists to Medicare in 2019. Proportions of services for each method were analyzed with respect to geographic region, years of dermatology experience, median income of the practice zip code, and rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) code.

Results

Fewer years of experience predicted a higher proportion of excisions (R2 = 0.7, p < .001) and higher odds of outlier excision performance. Outlier performance of excision was associated with practicing in the South, Midwest, and West, whereas outlier performance of destruction was associated with practicing in the Northeast and Midwest.

Conclusions

Dermatologists with less experience or in certain geographic regions performed more malignant excision relative to destruction. As the older population of dermatologists retires, the cost of care for NMSC may increase.

Introduction

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), which is comprised mainly of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), is the most common malignancy in the United States (Citation1,Citation2). Standard treatments include excision (surgical removal) and destruction (cryotherapy or curettage with or without electrodesiccation) in addition to Mohs micrographic surgery and myriad other methods. Multiple tumor and patient characteristics are taken into account when determining NMSC designation as low-risk or high-risk (Citation3). Mohs surgery is preferred for high-risk and cosmetically sensitive tumors, but other treatments can be more cost-effective when employed appropriately (Citation4,Citation5). Destructive modalities are an effective technique for certain NMSCs, provided they are primary, small, discrete, superficial to subcutaneous fat, and outside of terminal hair-bearing areas (Citation4,Citation5). Previous studies have found similar five-year recurrence rates between standard surgical excision and destruction for low-risk NMSC. A prospective cohort found no significant difference between a five-year recurrence rate of 4.9% for curettage and electrodessication (ED&C) and 3.5% for excision (Citation6). A systematic review of primary BCC estimated the five-year recurrence rate for curettage with electrodessication at 7.7%, cryotherapy at 7.5%, and standard surgical excision at 10.1% (Citation7). Another systematic review of SCC reported a 3.7% recurrence rate for ED&C compared with 8.1% for surgical excision (Citation8). Other evaluations of destructive modalities for select NMSCs have reported five-year recurrence rates of 4.3% for curettage alone (Citation9), 3.3% for ED&C (Citation10, p. 2], and 1–2% for curettage followed by cryosurgery (Citation11–14). Importantly, costs for excision are substantially higher and may include additional closure or facility charges (Citation15,Citation16). The cost of treating a 1.1 cm SCC on the arm with ED&C has been estimated at $360, compared to $710 with standard excision (Citation16). If the excision is performed at an ambulatory surgery center, the estimate rises to $2028 (Citation16). Regarding cosmesis, excision, and destruction can have similar rates of long-term satisfaction among patients (Citation17). For malignant lesions that allow it, destruction provides an acceptable cure rate and comparable esthetic outcome at a dramatically reduced cost.

Examining physician behavior in treating NMSC can help predict future costs and identify areas of potential optimization. The burden of treating NMSC is substantial at an estimated $4.8 billion annually in the US, and this expenditure has been rising (Citation18). The incidence of superficial BCC, which is often amenable to treatment with destructive modalities, has increased relative to other histologic subtypes (Citation19). Differences have been identified between dermatologists, otolaryngologists, plastic surgeons, and generalists in the usage of excision and destruction (Citation20). Previous research has found that dermatologists, on average, perform more destruction than excision for malignancy (Citation20–22). Treatment utilization for NMSC was compared between a private dermatology practice and a Veterans Affairs medical center, which revealed considerable variation that did not appear to be explained by clinical considerations between sites (Citation23). This study aimed to further explore possible differences in NMSC surgical treatment utilization on a wider scale. The primary objective for this study was to identify characteristics of dermatologists that are related to increased performance of excision or destruction for NMSC treatment. We analyzed factors associated with the performance of more malignant excision relative to destruction. We also analyzed factors associated with outlier behavior, which we defined as exclusive performance of excision or exclusive performance of destruction.

Methods

Claims for excision or destruction of malignant skin lesions by dermatologists were obtained from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment database, 2019 (Citation24). Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) integumentary codes were grouped as malignant excisions (CPT codes 11600–11646) and malignant destructions (CPT codes 17260–17286). Dermatologists who did not submit at least 10 instances of either malignant excision or malignant destruction were excluded from this dataset. A total of 6961 dermatologists, who performed an annual total of 351,063 malignant excisions and 545,908 malignant destructions, were included in the study. For each dermatologist, the proportions of each treatment method were calculated as follows:

‘Performing more excision’ was defined as submitting an above average proportion of excisions including only excisions, while ‘performing more destruction’ was defined as submitting an above average proportion of destructions including only destructions. Previous research on physician behavior in dermatology has designated outlier behavior as performance of greater than two standard deviations above the mean (Citation25–28). A substantial proportion of dermatologists in this dataset submitted only excisions or only destructions, leading to more than 2.5% of dermatologists with calculated treatment proportions of 0 or 1. Therefore, any dermatologist submitting only excisions or only destructions (who are herein also referred to as ‘exclusive performers’) was classified as either an excision outlier or destruction outlier.

The following physician characteristics were analyzed: geographic region, years of experience, median household income of the practice zip code, and rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) code. Practice locations were divided by state into Midwest, West, South, or Northeast according to the United States Census Bureau (Citation29). Physician enumeration date (National Plan & Provider Enumeration System National Provider Identifier Registry) (Citation30) was used to calculate years of dermatology experience as follows:

Years of dermatology experience were divided into quartiles of under 9 years, 9–17 years, 18–28 years, and over 28 years. Median household income, based on the practice location zip code, was divided into quartiles: under $54,770, $54,770–73,983, $73,984–99,764, and over $99,764. RUCA codes describe United States census tracts according to population density, urbanization, and commuting (Citation31). Metropolitan was separated from other designations (Micropolitan and Rural).

Additionally, CPT codes describe the location (Trunk, arms, legs; Scalp, neck, hands, feet, genitalia; or Face, ears, eyelids, nose, lips, and mucous membrane) and size in centimeters for a malignant lesion. The association between experience and treatment method was further investigated in subsets of malignant excision and destruction codes to identify possible associations between location and size with treatment method. Treatment utilization for malignancies of less cosmetically sensitive areas (trunk, arms, or legs) was compared with more cosmetically sensitive areas (face, ears, eyelids, nose, lips, mucous membranes, scalp, neck, hands, feet, and genitalia). NMSC size was also divided into ‘2 cm or less’ and ‘greater than 2 cm.’ As an approximation of which lesions might be most appropriate to treat with a destructive modality, procedures for NMSCs located on the trunk, arms, or legs that also measured 2 cm or less were also analyzed separately.

Chi-square tests were performed on the relative frequency of treatment method by covariates. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios for performing more of each method and for outlier status (exclusive performance of one method). Linear regression was performed on the mean proportion of excisions (out of all treatment of malignancy) by years of dermatologist experience. For the linear regression analysis, exclusive performers of excision were assigned proportions of ‘1’ and exclusive performers of destructions were assigned proportions of ‘0’. Data analysis was performed in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and significance was set at ɑ = 0.05.

Results

Dermatologists submitted to Medicare in 2019 a mean of 78 (95% CI 75–81) malignant excisions, compared to a mean of 106 (95% CI 101–112) malignant destructions. For dermatologists who performed both excisions and destructions, the excisions represented on average 47% of the total services for malignancy (95% CI 46–48). Of the dermatologists who submitted any malignant excision or destruction code, some performed only excisions (26%), whereas others performed only destructions (36%). Dermatologists who submitted only excisions performed a mean of 70 excisions (95% CI 66–75), while dermatologists who submitted only destructions performed a mean of 97 destructions (95% CI 91–104). A total of 45% of physicians performed an above average proportion of excisions or performed only excisions (subsequently referred to as ‘performing more excisions’), whereas 55% of physicians performed an above average proportion of destructions or performed only destructions (subsequently referred to as ‘performing more destructions’).

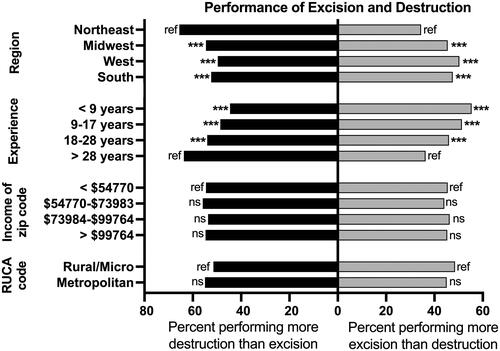

Performing more excisions was associated with practicing in the West, South and Midwest, whereas performing more destructions was associated with practicing in the Northeast (). Performing more excisions was also associated with under 9 years of experience, 10–17 years of experience, and 18–28 years of experience relative to greater than 28 years of experience. RUCA and median income of the practice zip code were not associated with performance of either method.

Figure 1. Percent of dermatologists who performed more destruction (including only destruction) or more excision (including only excision) for all NMSC. Dermatologist characteristics included geographic region, years of dermatology experience (quartiles), median household income of the practice zip code (quartiles), and rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) code. The percent of dermatologists who performed more destruction than excision (including only destruction) is shown on the left, in black, and the percent of dermatologists who performed more excision than destruction (including only excision) is shown on the right, in grey. Each stacked horizontal bar represents all dermatologists with the listed characteristic and sums to 100%. Odds ratios for performing more excision or more destruction were calculated relative to the reference group, with statistically significant differences noted. Ref: reference group; ns: not significant, * p < .05, ** p < .01, and *** p < .001.

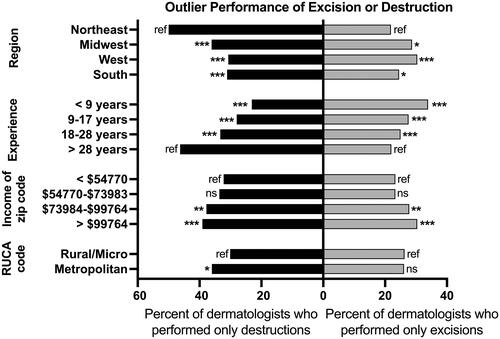

The groups of dermatologists who submitted only excisions or only destructions were considered outliers (). Dermatologists practicing in the South, Midwest, and West relative to the Northeast were more likely to be excision outlier performers (Also see Supplemental Digital Content 1). Outlier excision performance more likely in lower experience quartiles, whereas outlier destruction performance was more likely in higher experience quartiles. Outlier excision and exclusive destruction performance were associated with median household income of the practice zip code, with outlier performance of either method being more likely in the highest income quartile and the second highest quartile. Regarding RUCA code, dermatologists practicing in metropolitan areas were more likely to perform only destructions than those in rural or micropolitan areas.

Figure 2. Percent of dermatologists who performed only destructions or only excisions, which we defined as outliers, by covariate. Dermatologist characteristics included geographic region, years of dermatology experience (quartiles), median household income of the practice zip code (quartiles), and rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) code. The percent of destruction outlier dermatologists is shown on the left, in black, and the percent of excision outlier dermatologists is shown on the right, in grey. Each stacked horizontal bar represents the dermatologists performing only excision or only destruction with the listed characteristic. Odds ratios for performing only excision or only destruction were calculated relative to the reference group, with statistically significant differences noted. Ref: reference group; ns: not significant, * p < .05, ** p < .01, and *** p < .001.

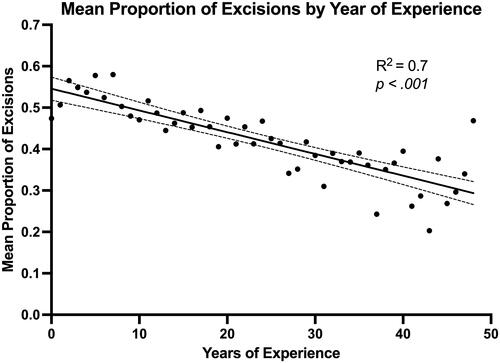

The association between years of experience and proportion of excisions was further investigated with linear regression. In this dataset, the extremes of experience represented relatively few dermatologists. Each year above 48 years of experience individually contained fewer than 10 dermatologists, and the range of 49–61 years represented 38 dermatologists or 0.5% of the dermatologists in the dataset. Similarly, physicians with −3–0 years of experience (had not completed dermatology residency yet) comprised 16 individuals or 0.2% of the dataset. Limiting the model to 1–48 years of experience strengthened the relationship between experience and proportion of excisions from R2 = 0.3–0.7 (p < .001, ).

Figure 3. Association between the mean proportion of services for excision and year of dermatology experience. Scatter plot and linear fit association between the years of experience that represented at least 10 dermatologists and the mean proportion of malignant excisions out of the sum of malignant excisions and malignant destructions. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence interval for linear regression.

Lastly, treatment utilization by experience level was analyzed with consideration of tumor location and size. For NMSCs located on the trunk, arms, and legs that measured 2 cm or less (‘low-risk’), we again saw more excision outlier performers in lower experience quartiles and more destruction outlier performers in higher experience quartiles (). This trend was also seen in tumors larger than 2 cm and tumors of the face, ears, eyelids, nose, lips, scalp, neck, hands, feet, or genitalia (Supplemental Digital Contents 2 and 3).

Table 1. Percent of dermatologists by experience who performed only destructions or only excisions, which we defined as outliers, for ‘low risk’ NMSC.

Discussion

This study analyzed dermatologists’ use of excisions and destructions to treat NMSC in the Medicare population. Dermatologists practicing in the Northeast performed more destruction and less excision than those in the Midwest, West, and South. Outlier performance of destructions was also more likely in the Northeast. Outlier status for excisions, defined here as exclusive performance of excision, was more likely for dermatologists in the Midwest, West, and South. With respect to RUCA code, this study suggests that urban or rural status may not be associated with NMSC treatment modality. This study also suggests that income of the practice zip code does not impact treatment choice if those performing an above average proportion of excisions are grouped with excision outliers. When looking at outliers, we saw that higher income quartiles had more exclusive performance of excision or destruction.

Years of dermatologist experience were associated with performance of excision or destruction in this study. Fewer years predicted a higher proportion of excisions, while more years predicted a higher proportion of destructions. These findings suggest substantial differences in NMSC treatment utilization with respect to experience. The most experienced dermatologists were twice as likely as the least experienced dermatologists to perform only destructions, whereas the inverse was true for excisions.

We also separated malignancies by location and size as denoted by CPT code. Standard surgical excision or Mohs surgery is generally recommended over destruction for lesions greater than 2 cm in diameter or those located in cosmetically sensitive areas (Citation4,Citation5). Even for lesions of 2 cm or less that were located on the trunk, arms, or legs, we again found that greater experience was associated with outlier performance of destruction while less experience was associated with outlier performance of excision. This suggests that the amount of time since training may influence a dermatologist’s approach to selecting treatment modalities for NMSC.

The observed differences in treatment utilization could be explained by a multitude of factors, including the types of NMSC presented for treatment, patient demographics, physician training, physician preference, or patient preference. Although previous studies have found no significant difference in five-year recurrence rate between excision and destruction for NMSC (Citation6–8), no randomized trials exist for controlled evaluation of these treatment methods. The lesions treated with excision versus destruction in existing cohort studies may not be equivalent, so it is difficult to calculate the true recurrence rates of different treatment modalities. The effectiveness of excisional and destructive techniques also depend, in part, on physician experience (Citation32,Citation33), so recurrence rates and cosmetic outcomes should be incorporated into future research. Regarding patient characteristics, health status is a factor in determining optimal therapy, with limited life expectancy and decreased functioning indicating less aggressive and less resource-intensive treatment modalities (Citation4, Citation5). Dermatology training may vary by location, with different modalities receiving more emphasis in certain regions. Additionally, training for NMSC management may have shifted over time from destruction to excisional treatments. Patient preference may also be considered for NMSC treatment, as it is frequently a nonfatal cancer with variability in acceptable options (Citation23).

Findings of this study must be interpreted with limitations in mind. Depth of invasion, location on the body, histologic subtype, and desired cosmetic result, among numerous other elements, are determinants of the appropriate treatment(s) for NMSC (Citation4,Citation5). Because this study analyzed deidentified annual procedure counts, detailed case information including recurrence was not available. Therefore, we could not account for possible differences in the characteristics of skin cancer presented for treatment or the recurrence rates associated with treatment choices. This study also only included claims submitted to Medicare, not private insurance. Medicare accounts for 42% of treatment costs for NMSC by one estimate (Citation18), so some dermatologists’ treatment patterns may not be accurately represented by these data. Additionally, excision and destruction are only two possible treatments for NMSC. Future studies should additionally examine physician phenotypes regarding the utilization of Mohs surgery relative to other methods.

This study describes outlier behavior in the dermatological treatment of NMSC using a recent nationwide dataset. Prior studies show that dermatologists are the primary specialty involved in the treatment of NMSC (Citation22,Citation34,Citation35). Given the dramatic cost differences between treatment options, performing excisions when destructions are acceptable increases the economic impact of treating NMSC. If dermatologists maintain a static approach to treatment over the course of their career, such a trend could lead to increased healthcare expenditure as the oldest dermatologists retire. The cost benefit of replacing some excisions with destructions can be approximated using previous literature, and future investigations should better evaluate this difference. If 20% of the 351,063 tumors excised in this study (assuming an average cost of $907 per excision) (Citation15) were to be treated destructively (average cost $392) (Citation15), the savings would reach $36 million. This would equal a 7% reduction in the total estimated cost of excisions and destructions procedures in this study. Residency programs should consider emphasizing destruction over excision as an acceptable treatment method for low-risk NMSC. Physician practice patterns impact the allocation of finite healthcare resources, and increased utilization of destructive methods could help curb the rising cost of treating NMSC.

Conclusions

According to 2019 Medicare data, dermatologists with less experience or in the Midwest, West, and South performed more malignant excisions than malignant destructions. Dermatologists with less experience or in the Midwest, West, and South were more likely to exclusively perform excisions (‘excision outliers’). Exclusive performance of destruction was more likely in dermatologists with more experience or practicing in the Northeast. Across lesion sizes and locations, we saw increased utilization of excision by less experienced dermatologists and increased utilization of destruction by more experienced dermatologists. Absent treatment paradigm shift over time, the cost of care for NMSC may increase as older dermatologists retire.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (145.9 KB)Disclosure statement

A. B. Fleischer is an investigator for Galderma and Trevi and a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, and SCM LifeScience. The remaining authors have indicated no significant interest with commercial supporters.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Data.CMS.gov ‘Medicare Physician & Other Practitioners - by Provider’ at https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners, reference number 24.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1–6.

- Skin cancer. 2022. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer

- Fahradyan A, Howell AC, Wolfswinkel EM, et al. Updates on the management of Non-Melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Healthc Basel Switz. 2017;5(4):E82.

- Kauvar ANB, Cronin TJ, Roenigk R, et al. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(5):550–571.

- Kauvar ANB, Arpey CJ, Hruza G, et al. Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment, part II: squamous cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(11):1214–1240.

- Chren MM, Linos E, Torres JS, et al. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1188–1196.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL.Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(3):315–328.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976–990.

- Backman E J, Polesie S, Berglund S, et al. Curettage vs. cryosurgery for superficial basal cell carcinoma: a prospective, randomised and controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(10):1758–1765.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Grin CM, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. Part 2: curettage-electrodesiccation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17(9):720–726.

- Nordin P, Stenquist B. Five-year results of curettage-cryosurgery for 100 consecutive auricular non-melanoma skin cancers. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(11):893–898.

- Nordin P, Larkö O, Stenquist B. Five–year results of curettage–cryosurgery of selected large primary basal cell carcinomas on the nose: an alternative treatment in a geographical area underserved by mohs’ surgery. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(2):180–183.

- Lindemalm-Lundstam B, Dalenbäck J. Prospective follow-up after curettage-cryosurgery for scalp and face skin cancers. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):568–576.

- Peikert JM. Prospective trial of curettage and cryosurgery in the management of non-facial, superficial, and minimally invasive basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(9):1135–1138.

- Wilson LS, Pregenzer M, Basu R, et al. Fee comparisons of treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice academic setting. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(4):570–584.

- Rogers HW, Coldiron BM. A relative value unit–based cost comparison of treatment modalities for nonmelanoma skin cancer: effect of the loss of the mohs multiple surgery reduction exemption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(1):96–103.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(7):1041–1049.

- Guy GP, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the US, 2002 − 2006 and 2007 − 2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(2):183–187.

- Arits A, Schlangen M, Nelemans P, et al. Trends in the incidence of basal cell carcinoma by histopathological subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):565–569.

- Chirikov VV, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, et al. Physician specialty cost differences of treating nonmelanoma skin cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74(1):93–99.

- Skaggs R, Coldiron B. Skin biopsy and skin cancer treatment use in the medicare population, 1993 to 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):53–59.

- Manternach T, Housman TS, Williford PM, et al. Surgical treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the medicare population. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(12):1167–1169; discussion 1169.

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Sands LP, et al. Variation in care for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice and a veterans affairs clinic. Med Care. 2004;42(10):1019–1026.

- Medicare physician & other practitioners - centers for medicare & medicaid services data. 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners

- Aggarwal P, Neltner SA, Fleischer ABJ. Risk factors that are associated with outliers in mohs micrographic surgery in the national medicare population, 2018. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48(2):181–186.

- Krishnan A, Xu T, Hutfless S, et al. Outlier practice patterns in mohs micrographic surgery: defining the problem and a proposed solution. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):565–570.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Analysis of outlier nail biopsy practice patterns in the medicare provider utilization and payment database 2012–2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):986–989.

- Peck GM, Wang Y, Fleischer AB, et al. Practice region and density, male sex, and specialty predict frequent performers of nail biopsies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;88:688–690.

- Census Regions and Divisions of the United States [Internet]. US Census Bureau; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

- NPPES NPI Files [Internet]. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 4]. Available from: https://download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html

- Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes [Internet]. U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx

- Kopf AW, Bart RS, Schrager D, et al. Curettage-Electrodesiccation treatment of basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(4):439–443.

- Paoli J, Gyllencreutz JD, Fougelberg J, et al. Nonsurgical options for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9(2):75–81.

- Smith ES, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, et al. Characteristics of office-based visits for skin cancer. Dermatologists have more experience than other physicians in managing malignant and premalignant skin conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(9):981–985.

- Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, White RE, et al. Procedures for skin diseases performed by physicians in 1993 and 1994: analysis of data from the national ambulatory medical care survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5 Pt 1):719–724.