Abstract

Uveitis is a rare adverse event of dupilumab, that typically affects both eyes and often leads to discontinuation of therapy. In this article, we report a case of a 28-year-old female with atopic dermatitis who developed new-onset iridocyclitis, a form of uveitis, in her left eye 2 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment, which improved after reducing the dose, without discontinuing dupilumab. The patient also experienced asymptomatic hypereosinophilia, possibly related to dupilumab, which was gradually relieved without discontinuation. With the readers, we share our experience in managing uveitis and hypereosinophilia associated with dupilumab, which may be helpful in managing these conditions and avoiding discontinuation of dupilumab.

Case presentation

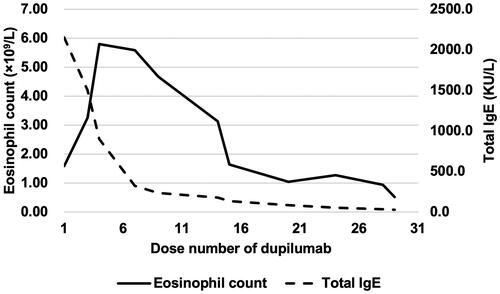

A 28-year-old female patient presented with a 1-year history of atopic dermatitis (AD, ). Her eosinophil count was 1.29 × 109/L (12.5% of total white blood cell count). The total IgE and specific IgE to cat dander were 3594 KU/L and 29.3 KU/L (level 4), respectively. Prior treatment included prednisolone, cyclosporin, omalizumab, and topical pimecrolimus, which led to minimal improvement of AD. The SCORAD index was 20.1, with an EASI score of 4 and a PP-NRS score of 8, suggesting a phenotype of mild lesions with severe itch (itch-dominant AD). The patient experienced severe skin pruritus and dryness, which significantly affected her sleep quality of life. The patient had allergic rhinitis and asthma but no history of allergic conjunctivitis.

Figure 1. (a) Erythemas and red papules could be seen on the cheeks, Chin, trunk and extremities including flexural distribution. The skin on the entire body was dry. (b) Signs on slit-lamp examination when the patient had ophthalmologic symptoms were consistent with uveitis. (c) No evident signs were found on slit-lamp examination after management.

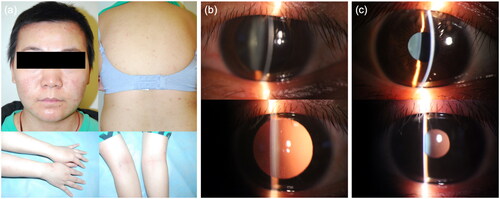

When the eosinophil count rose to 2.0 × 109/L (19.1% of total white blood cell count), accompanied by a total IgE level of 2494 KU/L, the patient began dupilumab subcutaneous injections of dupilumab at a starting dose of 600 mg followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. AD improved after the first dose of dupilumab. After the second dose, the patient developed new-onset redness and blurred vision in the left eye, which worsened after the third dose. Slit-lamp examination showed dust keratic precipitates, aqueous flare and floaters (). The patient was diagnosed with iridocyclitis, and treated with corticosteroid eye drops. The dose of dupilumab was reduced to 150 mg every 2 weeks. Three weeks later, uveitis completely resolved with no evident slit-lamp signs (). Dupilumab was not discontinued, and there was no recurrence of uveitis during a follow-up period of 20 months.

After the third dose of dupilumab, the patient developed hypereosinophilia. The eosinophil count increased to 5.80 × 109/L after the fourth dose, without AD relapse. Hematologic malignancy mutation was negative. A consultation with the hematology department suggested that hypereosinophilia was possibly associated with dupilumab. Dupilumab was not discontinued and the hypereosinophilia decreased. The eosinophil count decreased to 0.52 × 109/L after the 29th dose. shows changes in eosinophil count and total IgE level during dupilumab therapy.

Discussion

Although dupilumab has been associated with conjunctivitis and eye pruritus, uveitis was rarely reported (Citation1,Citation2). We report a case of a 28-year-old AD patient who developed new-onset iridocyclitis 2 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment, which improved after reducing the dose without discontinuing dupilumab. The possibility that dupilumab caused uveitis was accessed using the Naranjo algorithm, a method that determines the likelihood of whether an adverse effect is due to a certain drug (Citation3). The calculated Naranjo scale for our patient was 3 for these reasons: the adverse event appeared after the suspected drug was administered (+2), and the reaction was less severe when the dose was decreased (+1). According to the score, it is “possible” that dupilumab caused uveitis.

There were 5 cases of dupilumab-associated noninfectious uveitis reported in English literature, as summarized in . The ophthalmic symptoms in previous reports included redness, pain, impairment of visual acuity, and photophobia. These cases had pan uveitis (2 cases), anterior and intermediate uveitis, chorioretinitis, and posterior uveitis, respectively, which had more severe ocular inflammation and higher ophthalmic risks than our case. Ayasse et al. reported a 50-year-old AD patient who developed pan uveitis in both eyes uveitis after >1 year on dupilumab (Citation4), which was relieved after stopping dupilumab and recurred within 1 month of restarting the drug. Padidam et al. reported 4 AD patients with uveitis in both eyes during dupilumab treatment (Citation5). All 4 patients had a period of time longer than 6 months (>1 year, 2 years, 18 months, and 7 months, respectively) between dupilumab initiation and uveitis onset. In contrast, our case developed iridocyclitis (a form of uveitis) in one eye and in a shorter time after starting dupilumab. It might be supposed that lower severity might be associated with a shorter latent period, but this assumption needs further verification in larger-scaled studies.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of dupilumab-related uveitis previously reported.

Among the 6 cases (in the literature and our report), dupilumab was stopped in 4 cases and continued in 2 cases (case 3 in Padidam’s series and our case). Due to its effectiveness in AD, risk factors of uveitis-related dupilumab discontinuation are worth investigating and preventing if possible. In our case, the dupilumab dose was adjusted in a probable shorter time (2 weeks vs. ≥2 months in Ayasse’s case and in Padidam’s case 1, ≥6 months in Padidam’s case 2, with the others not reported), suggesting that earlier dose reduction might be related to milder uveitis and a lower risk of dupilumab discontinuation.

The mechanism of dupilumab-related uveitis remains unclear. In patients treated with other biologics, including etanercept, adalimumab, abatacept, infliximab and golimumab, cases of biologics-related sarcoid uveitis were reported (Citation6). The suggested mechanisms of biologics-related sarcoid uveitis include local or systemic cytokine imbalance (Citation7), increased susceptibility to infection (Citation8), and genetic susceptibility (Citation6). The precise mechanisms of biologics-related uveitis require further investigation.

Eosinophilia is not uncommon in patients treated with dupilumab (Citation9). Increased eosinophil counts compared to baseline were found in approximately 20% of real-world AD patients treated with dupilumab (Citation10). Hypereosinophilia (>1.5 × 109/L) was less common, occurring in 9.0% to 11.6% dupilumab-treated AD patients (Citation11,Citation12). The mechanism by which dupilumab influences eosinophil count was proposed that dupilumab might inhibit eosinophil migration into tissue by blocking the IL-4/13 axis, without affecting eosinophil production in bone marrow (Citation13). Although cases of organ damage related to dupilumab-related hypereosinophilia, including eosinophilic pneumonia, worsened asthma, eosinophilic pleural effusion, and thromboembolic diseases have been reported, dupilumab-related hypereosinophilia is usually transient and not associated with clinical consequences (Citation14,Citation15). Our patient had a maximum eosinophil count of 5.80 × 109/L but gradually improved without discontinuing dupilumab. This suggests that even if the eosinophil count is significantly elevated, dupilumab may not need to be discontinued close monitoring and evaluation by a hematologist for hypereosinophilia, which may spontaneously improve with continued dupilumab treatment.

This case underlined the importance of timely examination and management in patients with ophthalmologic symptoms during dupilumab treatment. Because the number of cases of dupilumab-associated uveitis is limited, large-scale, long-term studies and further surveillance are warranted.

Authors’ contribution

TW, DC and YL made the clinical diagnosis, designed the observational study and critically reviewed the article. SZ collected the clinical information, drafted the manuscript and revised the article. ZH, HS and LY performed acquisition of data in literature. LL and JF collected and analyzed the follow-up data. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed on all versions of the article.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the institutional ethics committee (S-k1773).

Patient consent

Written informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patient.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, TW, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ivert LU, Wahlgren CF, Ivert L, et al. Eye complications during dupilumab treatment for severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(4):1–3. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3121.

- Wu D, Daniel BS, Lai AJX, et al. Dupilumab-associated ocular manifestations: a review of clinical presentations and management. Surv Ophthalmol. 2022;67(5):1419–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2022.02.002.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154.

- Ayasse M, Lockshin B, Do BK, et al. A case report of uveitis secondary to dupilumab treatment for atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:98–99. Jandoi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.11.012.

- Padidam S, Raiji V, Moorthy R, et al. Association of dupilumab with intraocular inflammation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021; 7:1–6.

- Sobolewska B, Baglivo E, Edwards AO, et al. Drug-induced sarcoid uveitis with biologics. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;30(4):907–914. 19doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1850799.

- Kawashima M, Miossec P. Effect of treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with infliximab on IFN gamma, IL4, T-bet, and GATA-3 expression: link with improvement of systemic inflammation and disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64(3):415–418. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.022731.

- Xie X, Li F, Chen JW, et al. Risk of tuberculosis infection in anti-TNF-α biological therapy: from bench to bedside. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47(4):268–274. Augdoi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.005.

- Fargnoli MC, Esposito M, Ferrucci S, et al. Real-life experience on effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(5):507–513. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1682503.

- Francuzik W, Alexiou A, Worm M. Safety of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis: expert opinion. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2021; 20(9):997–1004. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1939673.

- Faiz S, Giovannelli J, Podevin C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in a real-life French multicenter adult cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):143–151. Juldoi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.053.

- Marcant P, Balayé P, Merhi R, et al. Dupilumab-associated hypereosinophilia in patients treated for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(6):e394–e396. Jundoi: 10.1111/jdv.17177.

- Olaguibel JM, Sastre J, Rodríguez JM, et al. Eosinophilia induced by blocking the IL-4/IL-13 pathway: potential mechanisms and clinical outcomes. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2022;32(3):165–180. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0823.

- Caminati M, Olivieri B, Dama A, et al. Dupilumab-induced hypereosinophilia: review of the literature and algorithm proposal for clinical management. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(7):713–721. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2022.2090342.

- Lommatzsch M, Stoll P, Winkler J, et al. Eosinophilic pleural effusion and stroke with cutaneous vasculitis: two cases of dupilumab-induced hypereosinophilia. Allergy. 2021;76(9):2920–2923. doi: 10.1111/all.14964.