Abstract

Background

Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common skin disease. Fire needle is a method of quickly piercing the local skin lesions with red-hot needles for AV. This work aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of fire needle combined with chemical peels for AV.

Methods

Eight databases including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Internet, Wanfang, Sinomed, and VIP databases were searched to enrolled randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing fire needle therapy combined with chemical peels with chemical peels alone. The risk of bias was evaluated by the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. Statistical analysis was completed by RevMan 5.3 and Stata 14.0.

Results

Altogether 18 studies including 1213 patients were enrolled. Compared with chemical peels alone, fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy improved the total effective rate (RR = 1.37,95% CI [1.26,1.48], p < 0.00001) and skin lesions (MD = −2.11, 95% CI [−2.74, −1.47], p < 0.00001), and reduced the recurrence rate (RR = 0.50,95% CI [0.33,0.76], p = 0.0009).The application of fire needle was associated with few adverse reactions, all of which were well tolerated and transient.

Conclusion

Fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy is effective and safe for AV. Nevertheless, more large-scale, well-designed clinical studies are warranted to provide evidence-based medical support.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris (AV) refers to a chronic inflammatory skin disease of the pilosebaceous follicles including sebaceous glands and hair follicles, which usually affects the face, chest, back and neck (Citation1). Clinically, it is characterized by open comedones (blackheads), closed comedones (whiteheads) and inflammatory lesions including nodules, pustules and papules (Citation2). AV may influence 9.4% of the global population, typically, it is the eighth most prevalent disease world, whose prevalence is estimated to range from just over 20% to over 95% (Citation3). In addition, AV is more frequent in males than in females, and its prevalence varies depending on country and ethnicity (Citation4). AV can not only bring physical effects like permanent scarring and disfigurement, but also has long-lasting psychosocial impacts affecting the patient’s quality of life. The comorbidities of acne including depression, social isolation and suicidal ideation should not be ignored (Citation5).

Currently, the first-line treatments for AV recommended by guidelines are conventional pharmacological therapies including antibiotics, retinoids, hormonal agents and benzoyl peroxide (Citation6,Citation7). However, there is an increasing concern about the global development of resistance in propionibacterium acnes and other bacteria to topical and oral antibiotics. Meanwhile, there may be a potential risk of adverse effects in association with topical and systemic treatments (Citation8,Citation9). Thus, conventional treatment is not always desirable, and alternative treatment options like monotherapy or more often combination therapy should be considered.

Acupuncture therapy, an ancient and integral part of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), is employed in treating numerous diseases including acne, which can ameliorate the deep-rooted mechanisms closely related to acne development (Citation10). Fire needle therapy, a form of acupuncture therapy, has been recommended by the Chinese Acne Treatment Guidelines with wide application in the treatment of AV (Citation11,Citation12). It is an external treatment method using a specific needle that is heated by an alcohol lamp until it burns red and is quickly stabbed into the local skin lesions. It could stimulate and dredge the meridians and accelerate the flow of qi and blood, thus improving inflammation and promoting lesion repair (Citation13–15). Non-pharmacological therapies in modern medicine including laser and light-based therapies, chemical peels like salicylic acid (SA), amino fruit acid (AFA), and mandelic acid (MA), and microneedling are also the alternative anti-acne treatments. In recent years, more clinical studies of fire needle therapy combined with chemical peels for the treatment of acne have emerged. Chemical peeling is a skin resurfacing procedure commonly applied for facial rejuvenation and esthetics, especially for acne. This therapy is one of the most common non-pharmacological therapies because it causes regeneration of a new epidermal layer of the dermal tissues, and has the advantage of being safe, convenient and inexpensive (Citation16).

To date, the relative efficacy and safety of fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy for the treatment of AV have not yet been systematically analyzed. As a result, this systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to assess the efficacy and safety of fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy for the treatment of AV and to provide evidence-based medical proof for the clinical application of this combined therapy.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out following guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Citation17) and registered in PROSPERO platform (CRD 42023399620).

Search strategy

This work searched a total of eight databases, namely, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Internet (CNKI), Wanfang, Sinomed, and VIP databases until 1 January 2023 for identifying the eligible studies. Search terms were as follows: fire needle, heat needle, fire needling, chemical peel, chemical resurface, α-hydroxy acid, amino fruit acid, glycolic acid, mandelic acid, tartaric acid, β-hydroxy acid, salicylic acid, azelaic acid, lipohydroxy acid, pyruvic acid, retinoic acid, trichloroacetic acid, acne vulgaris, comedo, pimple, whelk. The retrieval strategy combined subject words and free words, which was appropriately adjusted based on the corresponding database. Table S1 (Supplementary Material) present more detailed information of the search strategy used in each database. There were no limitations on languages and published status. In addition, this work also manually retrieved reference lists in enrolled articles together with web-based trial registries, which included ClinicalTrials.gov and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry trials to further identify related studies.

Selection criteria

Studies were included according to criteria below: (1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs). (2) Studies that enrolled cases confirmed with AV were included, with no restrictions on the grading of AV, country, race, age, or sex. (3) The experimental intervention was fire needle therapy combined with chemical peels, with no restriction on the course of treatment, acupuncture points or type of chemical peeling agent. Meanwhile, the chemical peels regimen served as the intervention for control group. Other basic treatments were consistent of both groups. (4) The primary outcome was the total effective rate. Typically, the efficacy was classified as cured, significantly effective, effective, and ineffective (Citation18). Thereafter, we determined the total effective rate below, the total effective rate = (‘cured’ case number + ‘significantly effective’ case number)/overall patient number × 100%. Secondary outcomes were skin lesions, recurrence rate, and adverse events.

The exclusion criteria were shown below: (1) Studies not involving fire needle treatment. (2) Studies with incomplete data or insufficient information, and (3) non-RCTs.

Study selection

All studies were reviewed by two authors (Peng Lin and Chenqi Guo) independently. Any disagreement was resolved by group discussion. After removing duplicate literature, the titles and abstracts were scanned to exclude irrelevant studies. Then, full texts of the remaining studies were read to identify the final eligible study.

Data collection

Two reviewers (Peng Lin and Yingdong Wang) extracted data independently and cross-checked in parallel. The extracted information included basic information (first author, publication year, country), baseline data (age, gender, sample size), interventional measures in both experimental and control groups, outcomes. Any disagreements during the process were resolved through the third reviewer (Jianfeng Zhang).

Quality evaluation of those included studies

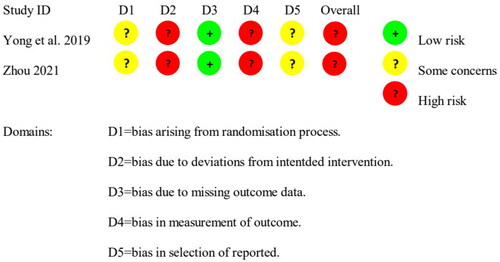

This work utilized the Cochrane risk-of-bias 2.0 (RoB2.0) tool (Citation19) for evaluating the bias risk for included trials by two reviewers independently (Cong Ma and Yiting Liu). Five domains were considered: bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in the measurement of the outcome, and bias in the selection of the reported result. In the end, a judgment of the overall risk of bias is generated. All items were divided into low risk, high risk, or some concerns. Disputes were settled down via a third party (Jianfeng Zhang).

Level of evidence

The GRADEpro guideline development tool (GDT) platform (https://gradepro.org) was used for evaluating outcome evidence level based on criteria of grades of recommendation, assessment, development and evaluation working (GRADE) (Citation20). In the GRADE system, quality was assessed into very low-quality (+), low-quality (++), moderate- quality (+++) and high-quality evidence (++++) with fully considerations of bias risk, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision as well as additional considerations.

Statistical analysis

This work utilized RevMan 5.3 software and Stata 14.0 software for performing statistical analysis. We analyzed dichotomous data by risk ratios (RR) together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), whereas continuous outcomes by mean difference (MD) together with 95% CI. Inter-study heterogeneities were analyzed by I2 statistics and χ2 test. I2≥50% or p ≤ 0.1 suggested a random-effects model should be selected, otherwise, a fixed-effects model should be adopted. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on intervention and comparison if appropriate. We also performed sensitivity analysis by Stata 14.0 in order to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis results. Additionally, the present work drew the funnel plot for assessing publication bias when the outcome index included more than 10 literatures.

Results

Literature retrieval results

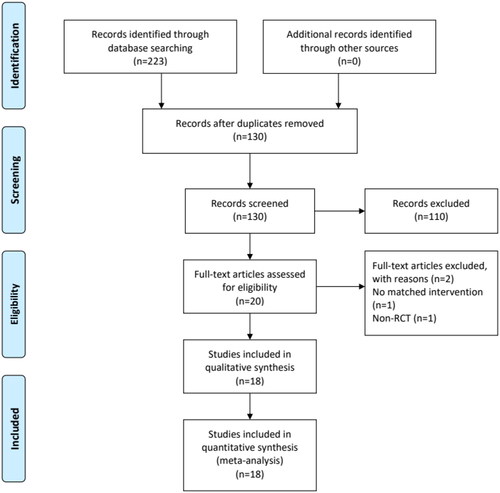

Initially, this work retrieved altogether 223 articles from the 8 electronic databases. Among them, 93 duplicates were removed. Afterwards, titles together with abstracts for those rest 130 articles were carefully read, while 110 studies were excluded. Afterwards, those rest articles were read in full-texts, and 2 were further eliminated. At last, this work enrolled 18 articles (Citation21–38) ().

Characteristics of the included studies

This meta-analysis enrolled 18 studies involving 1213 patients (608 and 605 patients from experimental and control groups). Each article was conducted in China and published between 2014 and 2022, and only the Chinese patients were recruited. The sample size was 16–60 for experimental group, whereas 15–60 for control group. Thirteen studies (Citation21–33) compared fire needle plus 30% supramolecular salicylic acid (SSA) and 30% SSA treatment alone. Four literatures (Citation34–37) compared fire needle combined with 20% AFA and 20% AFA treatment alone. There was only one study (Citation38) in which the experimental group received fire needle combined with 30% MA, and the control group received 30% MA alone. The treatment course ranged from 4 weeks to 6 months ().

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

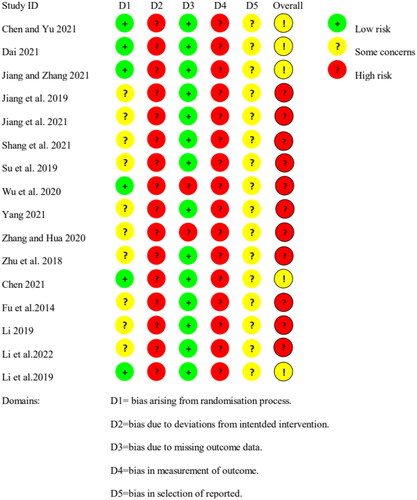

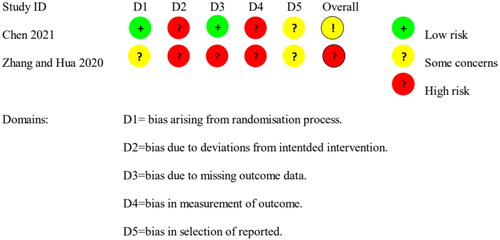

Methodological quality for enrolled articles

For the total effective rate outcome, the overall rating of five studies (Citation21–23,Citation34,Citation38) was ‘some concerns,’ and eleven studies (Citation24–29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation35–37) were rated as ‘high risk’ (). For the skin lesions outcome, one study (Citation34) was rated as ‘some concerns,’ and one study (Citation31) was rated as ‘high risk’ (). For the recurrence rate outcome, two studies (Citation30,Citation33) were both rated as ‘high risk’ (). For the adverse events outcome, twelve studies (Citation23–26,Citation29–33,Citation36–38) were rated as ‘high risk,’ and one study (Citation34) was rated as ‘some concerns’ ().

Figure 2. ROB for total effective rate. The included studies are evaluated by five domains and the overall risk of bias. All items were divided into low risk, high risk, or some concerns.

Figure 3. ROB for skin lesions. The included studies are evaluated by five domains and the overall risk of bias. All items were divided into low risk, high risk, or some concerns.

Systematic review and meta-analysis results

Total effective rate

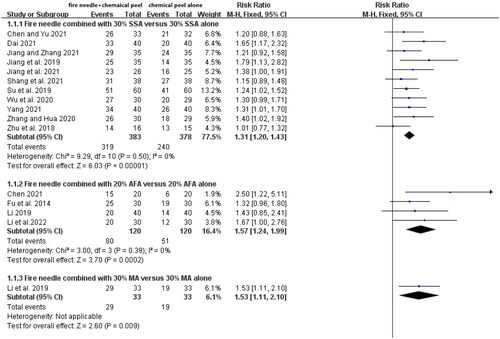

Sixteen studies (Citation21–29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–38) involving altogether 1067 patients (536 and 531 in experiment and control groups, separately) reported the total effective rate. Heterogeneity was not detected among the 16 studies (I2 = 3%, p = 0.42), so we selected a fixed-effects model. As revealed by meta-analysis, the total effective rate of fire needle therapy plus chemical peels therapy was higher than that of chemical peels alone group, with significant difference (RR = 1.37, 95% CI [1.26, 1.48], p < 0.00001). Meanwhile, 30% SSA the control intervention in 11 studies (Citation21–29,Citation31,Citation32), 20% AFA in 4 studies (Citation34–37), and 30% MA in 1 study (Citation38). Therefore, subgroup analysis stratified by types of chemical peels therapy was performed. Active treatment was more effective compared with control, no matter whether the chemical peels therapy was 30% SSA (RR = 1.31, 95% CI [1.20, 1.43], p < 0.00001), 20% AFA (RR = 1.57, 95% CI [1.24, 1.99], p = 0.0002), or 30% MA (RR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.11, 2.10], p = 0.009) ().

Figure 6. Forest plot of total effective rate. Forest graphs showing the risk ratios of total effective rate between the fire needle plus 30% supramolecular salicylic acid (SSA) and a control group of 30% SSA alone, between the fire needle plus 20% amino fruit acid (AFA) and a control group of 20% AFA alone, between the fire needle plus 30% mandelic acid (MA) and a control group of 30% MA alone.

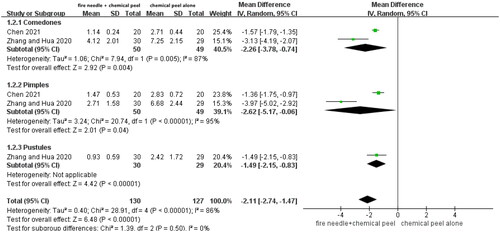

Skin lesions

Two studies (Citation31,Citation34) reported skin lesions, one including comedones, pimples, and pustules, and the other involving comedones and pimples. Considering the significant heterogeneity (I2 = 86%, p < 0.00001), we adopted a random-effects model. The experimental group had better performance in reducing skin lesions than the control group (MD = −2.11, 95% CI [−2.74, −1.47], p < 0.00001). Subgroup analysis was performed according to different skin lesions. As a result, the numbers of comedones, pimples, and pustules of experimental group after treatment decreased compared with control, with significant differences (MD = −2.26, 95% CI [−3.78, −0.74], p = 0.004; MD = −2.62, 95% CI [−5.17, −0.06], p = 0.04; MD = −1.49, 95% CI [−2.15, −0.83], p < 0.00001) ().

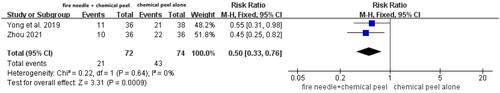

Recurrence rate

Two articles (Citation30,Citation33) mentioned the recurrence rate, of which, one had a follow-up period of 1 month, whereas the other one did not report the specific follow-up period. There was no data heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 0%, p = 0.64), so we adopted a fixed-effects model. According to our meta-analysis, experimental group had decreased recurrence rate compared with the control group, with the difference being statistically significant (RR = 0.50, 95% CI [0.33, 0.76], p = 0.0009) ().

Adverse events

In total, 13 studies (Citation23–26,Citation29–34,Citation36–38) reported the high safety and tolerability of fire needle combined with chemical peels therapy in the treatment of AV (). During the fire needle treatment, the experimental group might experience mild pain and slight redness, together with skin swelling. However, these adverse reactions resolved spontaneously without treatment. By contrast, the main side effects of the control group included dry skin and desquamation, which were mainly mild and disappeared within 1 week. Severe adverse events were not observed among all the enrolled articles.

Table 2. The details of adverse events.

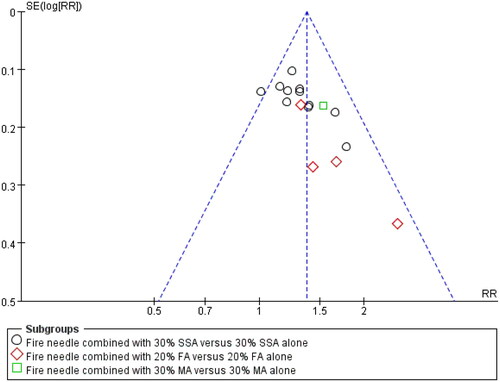

Publication bias

In funnel plot of total effective rate, the shape exhibited a slight asymmetry (), which suggested potential publication bias.

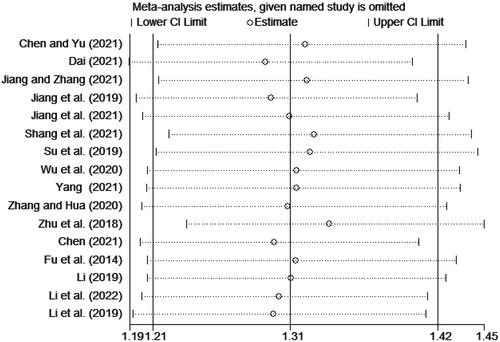

Sensitivity analysis

No significant influences on outcome of total effective rate after excluding individual studies one by one were found, suggesting that the pooled results were robust ().

Level of evidence

We used the GRADEpro GDT platform to evaluate the evidence on the efficacy of fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy in AV based on the GRADE criterion. The evidence of total effective rate was moderate-quality, skin lesions was evidence of very low, and recurrence rate was evidence of low-quality. Therefore, they were moderate or weak recommendations ().

Table 3. Summary of GRADE on the outcomes of the efficacy of fire needle combined with chemical peels therapy for AV.

Discussion

The present work assessed whether fire needle plus chemical peels therapy was effective and safe for the treatment of AV. As for outcome measures of total effective rate, skin lesions and recurrence rate, fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy was superior to chemical peels treatment alone. With regard to safety, the side effects during the treatment mainly included mild pain, slight redness and swelling of the skin, slight burning, dry skin and desquamation, which resolved spontaneously without any treatment. Furthermore, these side effects were transient and made no difference to treatment course. Therefore, fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy may be the safe option to treat AV.

The AV pathogenic mechanism involves multiple factors. Generally, four steps including increased sebum generation, changes in keratinization processes resulting in comedone generation, Propionibacterium acnes-mediated follicular colonization, as well as inflammatory factors surrounding pilosebaceous unit have been identified to exert an important effect on AV pathogenesis (Citation39). Among them, sebum abnormality accounts for a critical step, which is regarded as a prerequisite for acne. In other words, inhibiting sebum formation and secretion represents a key stage of acne treatment (Citation40). SA is a frequently utilized production for superficial peeling for acne, which can be ascribed to the specific lipophilic characteristics. The 30% SSA, a novel SA formulation, is an effective method for the treatment of AV, which achieves well tolerance with no obvious side effects (Citation41). As reported in previous studies, SSA efficiently decreased sebum production among individuals developing acne, which may take effect partly through modulating SREBP-1/FAS pathway (Citation42). AFAs are carboxylated acidic amino acids created by dissolution and acidification of natural acidic amino acids. AFA peels are effective for comedonal acne with less irritating and better tolerated (Citation43). MA is derived from hydrolysis of an extract of bitter almonds, which has potential medicinal activity and recognized antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, thus exerting a therapeutic effect on acne (Citation44).

In the TCM theory, the heat accumulation in Fei (Lung) and Wei (Stomach), blood stasis, dampness and emotional disorder are etiologic and pathogenic factors for acne (Citation45). Fire needle therapy can achieve the functions of both acupuncture and moxibustion (Citation46). On the one hand, acupuncture stimulation can enhance qi and blood circulation to stimulate healthy qi generation. Abundant healthy qi exerts a critical function in eliminating the harmful conditions of AV. On the other hand, the warm stimulation of moxibustion plays the roles of drawing out poison and purging heat, thus achieving the purposes of Qingre Qushi and Quxie Jiedu (Citation47). According to basic experimental studies, fire needle therapy can enhance the repair ability of local skin lesions, and its mechanism may be related to enhancing the function of phagocytes. Moreover, it can also accelerate the healing of damaged wounds by stimulating the release of various growth factors such as VEGF in the body (Citation48,Citation49). Therefore, fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy is an advisable treatment option.

We drafted the complete study protocol ahead of time. Various databases were searched, and different evaluation indicators including total effective rate, skin lesions, recurrence rate and safety were discussed. Moreover, this work adopted the GRADE system for assessing evidence level from multiple angles, which increased the credibility of the results. Collectively, evidence from 18 relevant RCTs suggested that fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy improved the total effective rate with security, which provided the recommendations and strategies in the treatment of AV. However, there were some limitations in the present work. First, the corresponding treatment strategy for AV is often formulated according to its specific grade. Due to the small number of included studies and available information, the clinical grading of AV was not taken into consideration. Secondly, although each enrolled study was RCT, they mostly had low methodological quality. Besides, all the studies included were conducted in China. The above-mentioned factors might have influence on our results. Thirdly, only 2 studies reported the outcome indicators of skin lesions and recurrence rate. Only 1 study reported the specific follow-up time for recurrence. Fourthly, the quality of evidence in this study was moderate, low, or very low according to the GRADE assessment system. Consequently, treatment protocols should be made cautiously with the comprehensive consideration of all the situations of acne sufferers.

Conclusion

Fire needle adjuvant chemical peels therapy may have efficacy and good safety in the treatment of AV.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (174.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are stored in Tianjin academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated hospital (Tianjin, China), and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945–973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037.

- Layton AM, Thiboutot D, Tan J. Reviewing the global burden of acne: how could we improve care to reduce the burden? Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):219–225. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19477.

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(4):1080–1083. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13765.

- Gieler U, Gieler T, Kupfer JP. Acne and quality of life – impact and management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(Suppl 4):12–14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13191.

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.019.

- Jorgaqi E, Savo I, Koraqi A, et al. Efficacy of acne vulgaris treatment protocols according to its clinical forms. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e1361. doi: 10.1111/dth.13611.

- Scott AM, Stehlik P, Clark J, et al. Blue-light therapy for acne vulgaris: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(6):545–553. doi: 10.1370/afm.2445.

- de Vries FMC, Meulendijks AM, Driessen RJB, et al. The efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a systematic review and best-evidence synthesis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(7):1195–1203. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14881.

- Chen CY, Xu GY, Shang YY, et al. Acupuncture: a therapeutic approach against acne. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(12):3829–3838. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14487.

- Xing M, Yan X, Sun X, et al. Fire needle therapy for moderate-severe acne: a PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2019;44:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.04.009.

- Ju Q. Working group for acne diseases Chinese Society of Dermatology. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of acne (the 2019 revised edition). J Clin Dermatol. 2019;48:583–588. doi: 10.16761/j.cnki.1000-4963.2019.09.020.

- Zhang Y, Jiang JS, Kuai L, et al. Efficacy and safety of fire needle therapy for flat warts: evidence from 29 randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:9513762. doi: 10.1155/2021/9513762.

- Chen J, Wang XX, Wang K, et al. Fire needle for recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a protocol for systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022;101(6):e28731. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028731.

- Huang G, Yan J, Zou JH, et al. Fire needle therapy for blood stasis syndrome of plaque psoriasis: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100(13):e25312. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025312.

- Chen XM, Wang S, Yang M, et al. Chemical peels for acne vulgaris: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019607. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019607.

- Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Zheng Q, Gu YD, Cao YY, et al. Runzaozhiyang capsules in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a systematic review. Chin J Derm Venereol. 2018;32(6):689–696. doi: 10.13735/j.cjdv.1001-7089.201711076.

- Sterne J, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026.

- Chen XM, Yu LJ. Nursing experience of fire needle combined with supramolecular salicylic acid peeling for facial acne. Chinese Baby. 2021;(21):236–237.

- Dai F. Clinical efficacy of fire acupuncture in treating acne. Changshou. 2021;8:113–114.

- Jiang XB, Zhang WX. Observation on the clinical efficacy of fire needling quenching combined with supramolecular salicylic acid on mild to moderate facial acne vulgaris. Heilongjiang J Tradit Chin Med. 2021;50(2):46–47.

- Jiang LJ, Guo HY, Sun XJ, et al. Application value of fire acupuncture combined with new supramolecular salicylic acid nursing in mild to moderate facial acne vulgaris. Yiyaojie. 2019;(24):66.

- Jiang M, Duan JJ, Li L, et al. Efficacy observation of supramolecular salicylic acid combined with fire acupuncture in the treatment of mild to moderate acne. Chin J Dermato Venerol Integ Trad W Med. 2021;20(1):63–65.

- Shang XX, Liu YG, Yan F, et al. Observation of curative effect of filigree fire needle combined with supramolecular salicylic acid in the treatment of moderate to severe acne. Derm and Venereol. 2021;43(5):685–686.

- Su H, Chen LQ, Ceng XY, et al. Curative effect observation and nursing experience of fire acupuncture combined with 30% supramolecular salicylic acid peeling in the treatment of facial acne. J Ext Ther Tradit Chin Med. 2019;28(2):60–61.

- Wu PH, Wang L, Li QJ, et al. Evaluation of the clinical effect of acupuncture on scar formation after IV severe acne. Chin J Plast Surg. 2020;36(12):1324–1330.

- Yang Y. Clinical observation of oral isotretinoin combined with 30% supramolecular salicylic acid and fire acupuncture in the treatment of moderate to severe facial acne. Diet Health. 2021;12:94–95.

- Yong YX, Du XS, Du Y. Clinical curative effect of fire needle combined with new supramolecular salicylic acid on moderately severe acne. J Mil Surg Southwest China. 2019;21(2):133–136.

- Zhang X, Hua YJ. Efficacy observation of fire needling combined with supramolecular salicylic acid in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Derm and Venereol. 2020;42(1):66–68.

- Zhu LL, Li J, Li XD, et al. The therapeutic effect of new supramolecular salicylic acid combined with fire acupuncture in the treatment of mild to moderate facial vulgaris acne. Chin J Aesth Plast Surg. 2018;29(8):469–471.

- Zhou JF. Clinical effect of fire needling combined with new supramolecular salicylic acid in the treatment of moderate to severe acne. Diet Health. 2021;40:28–29.

- Chen X. Effects of fire needle combined with fruit acid rejuvenating on serum FSH, LH, E2 levels and skin lesions in acne patients. Modern Medicine and Health Research. 2021;5(3):94–96.

- Li JC, Li YN, Han JY, et al. Clinical observation on 60 cases of acne treated by fire needle combined with fruit acid. Medical Diet and Health. 2022;20(12):37–41.

- Fu Y, Jiang M, Sun J. Study on therapy effect of fire needling combined with fruit acid on the acne. Chinese J Aesth Med. 2014;23(1):63–65.

- Li JC. Observation on the curative effect of fire needle combined with fruit acid in treating acne. Chinese Manipul Rehab Med. 2019;10(8):32–33.

- Li J, Han FX, Yu L, et al. Therapeutic effect of fire needle combined with almond acid on mild and moderate facial acne. Chinese J Dermatovenereol Integr Trad West Med. 2019;18(3):252–254.

- Hazarika N. Acne vulgaris: new evidence in pathogenesis and future modalities of treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(3):277–285. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1654075.

- Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(10):821–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x.

- How KN, Lim PY, Wan Ahmad Kammal WSL, et al. Efficacy and safety of Jessner’s solution peel in comparison with salicylic acid 30% peel in the management of patients with acne vulgaris and postacne hyperpigmentation with skin of color: a randomized, double-blinded, split-face, controlled trial. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(7):804–812. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14948.

- Lu J, Cong T, Wen X, et al. Salicylic acid treats acne vulgaris by suppressing AMPK/SREBP1 pathway in sebocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(7):786–794. doi: 10.1111/exd.13934.

- Ilknur T, Demirtaşoğlu M, Biçak MU, et al. Glycolic acid peels versus amino fruit acid peels for acne. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12(5):242–245. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.514919.

- Dayal S, Kalra KD, Sahu P. Comparative study of efficacy and safety of 45% mandelic acid versus 30% salicylic acid peels in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(2):393–399. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13168.

- Zhang TB, Bai YP, Yang HY, et al. Efficacy of modified Qufeng Runmian powder on acne vulgaris with syndromes of dampness and blood stasis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2020;26(7):490–496. doi: 10.1007/s11655-020-3214-4.

- Liu HC. Observation on the effect of fire needling combined with isotretinoin in the treatment of moderate to severe acne. Derm Venereol. 2021;43(5):684–688.

- Deng H, Shen X. The mechanism of moxibustion: ancient theory and modern research. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:379291. doi: 10.1155/2013/379291.

- Hu FM, Ding SW, Wang P, et al. Observation on the curative effect of fire needle therapy combined with Jiedu recipe in the treatment of moderate and severe acne vulgaris. Jiangxi J Tradit Chin Med. 2021;52(4):57–59.

- Luo YR, Li JL. Clinical research progress of fire acupuncture in the treatment of acne. Gansu Med J. 2022;41(1):4–6.