Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of an over-the-counter (OTC) 1% colloidal oatmeal cream versus a ceramide-based prescription barrier cream in children with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) were previously described.

Objectives

Here, findings are reported for the Black/African American subgroup.

Methods

Patients were randomized to 1% oatmeal cream or prescription barrier cream twice daily or as needed for three weeks. Assessments included Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, Investigator’s Global Atopic Dermatitis Assessment (IGADA) scores, and patients’/caregivers’ assessment of eczema signs and symptoms.

Results

Overall, 49 Black/African American children aged 2–15 years with mild/moderate AD were included. At week 3, mean (SD) changes from baseline in EASI scores were −2.4 (1.7) with 1% oatmeal cream and −2.1 (2.3) with barrier cream; improvements were observed from week 1. At week 3, mean (SD) changes from baseline in IGADA scores were −0.6 (0.7) and −0.7 (0.6), respectively. Improvements in subjective ratings of signs/symptoms of eczema were observed. Both study treatments were well tolerated.

Conclusion

OTC 1% oatmeal cream was at least as effective and safe as prescription barrier cream in this population, providing a novel, fast-acting, and cost-effective option for the symptomatic treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in Black/African American children.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), one of the most common conditions among children in the United States (US), has been shown to be equivalent in quality of life (QoL) impact to non-dermatologic chronic disorders such as renal disease, cystic fibrosis, and asthma (Citation1,Citation2). This immune-mediated disease characterized by the infiltration of T cells and dendritic cells (Citation3), upregulation of inflammatory mediators (Citation4), and aberrant skin pathobiology (e.g. epidermal hyperplasia (Citation5), epidermal barrier defects (Citation6), changes in the composition of ceramides in the stratum corneum (Citation7)), leads to increased water loss, pH imbalance, and decreased skin hydration (Citation8,Citation9).

The prevalence of AD varies widely depending on race and ethnicity, which suggests that genetic, social, or environmental factors may influence disease expression (Citation10,Citation11). In the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey survey, prevalence rates were 19.3% and 16.1% in Black and White children, respectively (Citation12), while even higher prevalence rates (up to 23%) have been reported in children in African countries (Citation13). Even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors (e.g. health insurance, metropolitan living, income), Black children are 1.7 times more likely to develop AD compared with White children (Citation10). Black children are three times more likely to attend a dermatology visit for a diagnosis of AD compared with White children, despite being less likely to seek dermatological care, suggesting potential discrepancies in disease awareness and a greater degree of disease burden in individuals with skin of color (Citation14).

Black patients with AD are more likely to experience a greater frequency of extensor involvement, diffuse xerosis, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis than White patients (Citation15,Citation16). The presentation of lichenification and prurigo nodularis are thought to be indicative of a greater intensity of pruritus (Citation15). Furthermore, resolved lesions in Black patients are more likely to display dyspigmentation (Citation15,Citation16). These racial and ethnic variations in presentation and difficulties in discerning AD signs in darker skin (e.g. erythema) may contribute to greater disease severity before diagnosis in individuals with skin of color (Citation17).

There are also unique treatment challenges in this population, including an increased incidence of corticosteroid-induced hypopigmentation (Citation18), and some studies suggest that Black patients are at greater risk of dry skin because of increased transepidermal water loss (Citation19,Citation20) and decreased ceramide-to-cholesterol ratio (Citation21). Despite these ethnic differences in AD presentation and severity, the treatment of eczema is similar in all individuals with AD, with the principal aim of soothing pruritus and reducing inflammation; however, hydrating the stratum corneum and restoring the skin barrier are also helpful and contribute to alleviation of symptoms (Citation22). Recommended first-line agents in children include non-steroid emollients (creams and ointments), which should be used regularly; topical corticosteroids, which may be required sparingly to treat inflammation; and systemic treatments such as dupilumab, prednisolone, cyclosporine, and azathioprine, which are reserved for children with severe AD (Citation23–26).

Colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa), composed of various phytochemicals (Citation27), is a safe and effective ingredient in a variety of skin care products (Citation28,Citation29) and is the only over-the-counter (OTC) skin protectant indicated by the US Food & Drug Administration for the treatment of eczema symptoms (Citation30). Despite the higher prevalence of AD in children with skin of color, there is a lack of clinical evidence for the use of colloidal oatmeal in this population. Oatmeal contains a variety of lipids that help restore the skin barrier by promoting epidermal differentiation, lipid synthesis, and ceramide processing, and reducing transepidermal water loss (Citation27). Furthermore, colloidal oatmeal helps normalize the skin pH, which also enhances the barrier function of the skin (Citation27–29).

In a study in children (N = 90) with mild-to-moderate AD, which included a large subset of Black or African American children (54%), an OTC 1% colloidal oatmeal cream was shown to be equally as effective and safe as a steroid-free prescription barrier cream (Citation9). The prescription ceramide-containing barrier cream includes three essential lipids (ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids), which replenish the skin’s natural level of these lipids to help repair the skin barrier (Citation31). Given the clinical, epidemiologic, and molecular differences among various ethnic phenotypes, it is important to ascertain whether race can affect clinical outcome and whether there are differences in the performance of an OTC cream compared with standard prescription treatment. Herein we report the findings of a post hoc analysis evaluating the effectiveness and safety of the 1% colloidal oatmeal cream in the cohort of Black or African American children with mild-to-moderate AD in the aforementioned study.

Materials and methods

Study design

The methodology for the randomized, double-blind, two-arm trial (NCT01326910) has been reported previously (Citation9) and the key points are summarized below. The study was approved by an independent Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from patients (>7–18 years) and from the parent or legal guardian if the patient was 6 months–7 years of age.

Following screening, eligible patients were instructed to avoid the use of moisturizer or emollient and use only a mild body wash (Johnson’s® Head to Toe®; Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc.) for the next two days prior to starting the application of assigned product. At the baseline visit, patients were randomized 1:1 to either treatment supplied in tubes for topical application: the OTC 1% colloidal oatmeal cream (formula 19306–127; Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc.) or prescription ceramide-containing barrier cream (EpiCeram® Skin Barrier Emulsion [Promius Pharma, LLC]). Patients and/or parents/caregivers were instructed to apply the cream twice daily or as needed for three weeks. Patients continued use of the body wash provided at screening for the duration of the study. Clinical and safety assessments were performed at baseline (day 0), and days 7 (week 1), 14 (week 2), and 21 (week 3), or on the day of patient discontinuation.

Patients

Patients aged 6 months–18 years with mild-to-moderate AD (graded between 3.0 and 7.5 inclusive; Hanifin and Rajka criteria (Citation32)) were eligible for enrollment in the original study. Concomitant use of Class IV–VII corticosteroids was permitted but eligibility for those using immunomodulators was at the physicians’ discretion. Key exclusion criteria were AD requiring systemic, super-potent (Class I) or potent (Classes II or III) topical corticosteroids or >2.0 mg/d inhaled or intranasal corticosteroids, and any topical or systemic therapy for viral, mycotic, or bacterial diseases. For the post hoc analysis, two cohorts of patients were used: those who self-identified (or parents/legal guardian on behalf of the patient) as Black or African American, and all others (White, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or Other) we refer to as non-Black or African American.

The authors acknowledge that the clinical study was conducted in 2011 when terms such as ‘African American’ were used to describe descendants of slaves in America. Today, however, the term ‘Black’ is preferred as it more accurately describes members of the African diaspora who were spread throughout the world but identify as a group. This term is more appropriate as it includes Black subjects in the US who are of the Caribbean origin or who may have migrated more recently from Africa, South America, Europe, or beyond.

Endpoints

AD severity was assessed according to the change from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (Citation33) at week 3 (primary endpoint) and at weeks 1 and 2 (secondary endpoints). A trained dermatologist evaluated the EASI according to the age-specific percentage of affected area in four regions (head/neck, trunk, upper and lower limbs). Another secondary endpoint was change from baseline in the Investigator’s Global Atopic Dermatitis Assessment (IGADA; 0 = Clear, 1 = Almost clear, 2 = Mild, 3 = Moderate, 4 = Severe, 5 = Very severe) at weeks 1, 2, and 3. QoL questionnaires of patient’s and/or caregiver’s assessment of signs and symptoms of eczema (itch, skin appearance, dryness/flakiness, redness, moisturization, sleep quality), product rating, and overall product performance for AD were completed. Adverse events (AEs) were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

This post hoc analysis of the efficacy and safety/tolerability of colloidal oatmeal cream or prescription ceramide-containing barrier cream was exploratory to evaluate effectiveness in Black or African American children; therefore, descriptive statistics are provided. As described in the original trial (Citation9), the efficacy and safety analyses were based on the intent-to-treat population of all patients who received the study treatment. Baseline information for the non-Black or African American population is provided for reference, but this analysis is not intended to compare the efficacy and safety in these groups.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

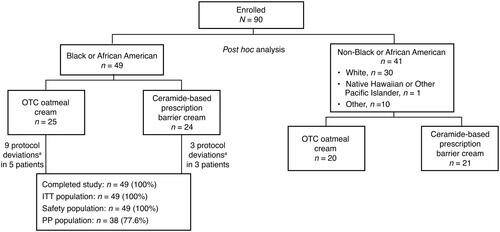

In this post hoc analysis, 49 Black or African American patients received either colloidal oatmeal cream (n = 25) or prescription ceramide-containing barrier cream (n = 24) (). The mean (standard deviation, SD) age of patients was 7.7 (3.7) years and 49% were male (). The severity of AD was moderate in the majority of patients and was comparable between Black or African American (73.5%) and non-Black or African American (70.7%) cohorts ( and Supplementary Table 1). Mean [SD] baseline EASI scores overall were higher in Black or African American patients (3.4 [2.1]) compared with the non-Black or African Americans (3.0 [3.7]). The trend toward more severe disease at baseline in the Black or African American cohort relative to non-Black or African American cohort was further supported by the mean [SD] IGADA score (2.3 [0.5], 2.0 [0.7]), patients’ assessment of dryness/flakiness (3.3 [2.1], 4.7 [2.7]), and moisturization (3.4 [1.8], 4.0 [2.4]).

Figure 1. Patient disposition. aDeviations included missed applications, incorrect completion of the study diaries or questionnaires, failure to return the creams, and incorrect calculation of study cream weight. ITT: intent-to-treat; OTC: over-the-counter; PP: per protocol.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline disease characteristics in the Black or African American cohort (ITT population).

Efficacy

In Black or African American patients, the mean (SD) change from baseline in EASI score at week 3 was −2.4 (1.7) and −2.1 (2.3) in the colloidal oatmeal cream and prescription barrier cream groups, respectively (). The improvement of EASI scores at all follow-up time points was similar for both treatment groups, which were seen as early as week 1. There was a similar improvement in IGADA scores from baseline at each time point in both treatment groups. The mean change from baseline at week 3 was −0.6 (0.7) for colloidal oatmeal cream and −0.7 (0.6) for prescription barrier cream ().

Table 2. Mean EASI and IGADA scores at baseline and over time and change from baseline scores in Black or African American patients (ITT population).

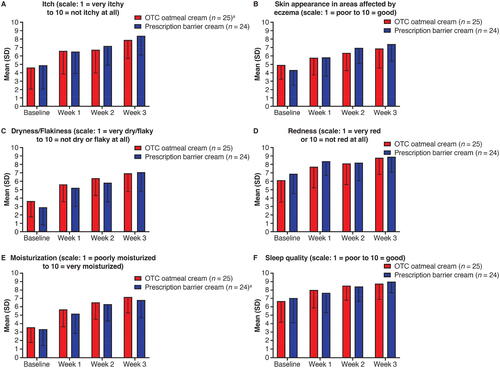

There was a progressive improvement in rating of signs and symptoms of eczema at each follow-up time point for both treatment groups of Black or African American patients. Improvement in these subjective ratings was rapid, with the following percentage change from baseline to week 1 for colloidal oatmeal cream and prescription barrier cream, respectively: itch (43.1%, 33.3%), skin appearance (18.0%, 34.9%), dryness/flakiness (54.8%, 80.3%), redness (26.0%, 21.7%), moisturization (59.6%, 55.2%), and sleep quality (19.9%, 8.9%). By week 3, mean ratings for skin appearance, dryness/flakiness, redness, moisturization, and sleep quality improved by approximately 2 or more points for both treatment groups ().

Figure 2. Black or African American patients’ and/or caregivers’ assessment of eczema signs and symptoms by time point based on 10-point scales: (A) itch; (B) skin appearance; (C) flakiness; (D) redness; (E) moisturization; (F) sleep quality, all in the ITT population. aWeek 1 data missing for one patient. ITT: intent-to-treat; OTC: over-the-counter; SD: standard deviation.

Patients and/or caregivers reported that they were more satisfied with their study cream than their normally used product at week 3, with mean ratings two points higher than their normally used product at baseline (). In the colloidal oatmeal cream group, 88.0% indicated they would use the study cream daily rather than occasionally, 96.0% thought that the product was appropriate for use on the entire body, and 100% and 88.0% indicated that the cream was appropriate for children and the whole family, respectively (). Assessment results were similar in the prescription barrier cream group with the exception of a lower percentage who felt that it was appropriate for use over the entire body (75%).

Table 3. Black or African American patients’ and/or caregivers’ assessment of eczema by time point: product rating (ITT population).

Table 4. Black or African American patients’ and/or caregivers’ assessment of the product for eczema at week 3: overall product (ITT population).

Safety

Overall, the number of Black or African American patients reporting AEs was very low, and the severity and nature of the AEs were similar for both treatment groups. One or more AEs were reported by four (16.0%) patients treated with colloidal oatmeal cream (pruritus [n = 2], pruritic rash [n = 1] and seasonal allergy [n = 1]), compared with one (4.2%) patient treated with barrier cream (pruritus). One of the cases of pruritus and the case of pruritic rash in the colloidal oatmeal cream group were possibly treatment-related. Both AEs resolved on the day of reporting without any change to treatment dose/frequency. There were no serious AEs or AEs that resulted in withdrawal from the study.

Discussion

AD usually manifests in early childhood (Citation34) and is highly prevalent in patients with skin of color (Citation16). Patients with darker skin often present with more treatment-resistant AD (Citation16), yet the majority of patients with AD studied in clinical trials are of White race (Citation35). Consequently, there are few published analyses on the efficacy of AD therapies specifically in adults and children with skin of color (Citation16).

The clinical benefits observed in this post hoc analysis of Black or African American children with mild-to-moderate AD in terms of reducing the severity and affected areas of eczema and symptoms compare favorably with the non-Black or African American cohort (n = 41) and overall population (N = 90) from the same study (Citation9). Previous studies in adults and children with AD treated with 1.0% colloidal oatmeal cream reported similar improvements in itch severity, IGADA scores, and EASI scores after two to eight weeks of treatment (Citation36–38).

The reduction of pruritus and the progressive improvement in other symptoms such as skin appearance, dryness/flakiness, and moisturization were observed with both creams. These investigator- and patient-assessed improvements in symptoms of AD are reflected in the product rating scores for the colloidal oatmeal and prescription barrier cream. Black or African American children, including their parents or caregivers, expressed greater satisfaction with the study creams over their currently used product, and regarded the creams as appropriate for adults and children, and for local application to eczema patches. One notable difference was the higher proportion favoring the colloidal oatmeal cream (96% vs 75%) for application over the entire body. Both study creams were considered easy to apply and there was a preference for daily use, which suggests both formulations are equally convenient and easy to use.

Colloidal oatmeal cream is an OTC product and thus may be more accessible to populations that experience health disparities with uncertain insurance coverage compared with prescription barrier cream (Citation14,Citation39,Citation40). As of July 2022, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (Medicaid) covered 40,901,520 children, representing 46.6% of all public assistance patients (Citation41). As of 2018, 20.8% of children covered through public assistance identified as Black but represented 14% of the US child population (Citation42). In a survey of Medicaid formularies for all 50 states plus District of Columbia, the least-covered agents for AD included many topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors recommended as first-line therapy (Citation43). Emollients were covered by 6% of states (three states), so the prescription barrier cream included here would likely not be covered. Restricted access to covered therapies reduces the chances of improvement and limits the ability of physicians to control a patient’s condition. In a similar survey of data collected from patient medical records at an urban academic medical center in Baltimore between 1 August 2013 and 1 August 2018, Black patients were less likely to receive certain dermatologic medications, including tacrolimus, crisabarole, and dupilumab, than their White or Caucasian counterparts (Citation44).

These statements in no way suggest that colloidal oatmeal replace either corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors in the armamentarium of available therapies employed to manage atopic dermatitis. Rather, colloidal oatmeal should be considered a suitable option for the maintenance of this chronic, incurable condition so that corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors can be used when they are most effective to reduce symptoms during flares and decrease unnecessary adverse side effects.

In summary, colloidal oatmeal cream is efficacious and well tolerated in Black or African American children with mild-to-moderate AD when used at least twice daily. There were no safety issues reported in Black or African American children, and the incidence of AEs was comparable with the prescription barrier cream.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (139.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Paul Zhang for his contributions. Medical writing assistance was provided by Stuart Murray, MSc, of Evidence Scientific Solutions and funded by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. a subsidiary of Kenvue.

Disclosure statement

Toni Anne Lisante and Menas Kizoulis are employees of Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. a subsidiary of Kenvue. Christopher Nuñez is an employee of Janssen Global Services, LLC. Corey Hartman serves as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, Scientis, Unilever, and L’Oréal; conducts clinical trials for Galderma, AbbVie, Revision Skincare, Scientis, and SkinBetter; and serves as a speaker for Johnson & Johnson, Skinceuticals, Allergan, Galderma, Scientis, and Revision Skincare.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lifschitz C. The impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000370226.

- Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07185.x.

- Fujita H, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Lesional dendritic cells in patients with chronic atopic dermatitis and psoriasis exhibit parallel ability to activate T-cell subsets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.016.

- Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Progressive activation of TH2/TH22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.012.

- Khattri S, Shemer A, Rozenblit M, et al. Cyclosporine in atopic dermatitis modulates activated inflammatory pathways and reverses epidermal pathology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1626–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.003.

- Agrawal R, Woodfolk JA. Skin barrier defects in atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(5):433. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0433-9.

- Blaess M, Deigner HP. Derailed ceramide metabolism in atopic dermatitis (AD): a causal starting point for a personalized (basic) therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(16):3967. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163967.

- Fowler JF, Nebus J, Wallo W, et al. Colloidal oatmeal formulations as adjunct treatments in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(7):804–807.

- Lisante TA, Nuñez C, Zhang P. Efficacy and safety of an over-the-counter 1% colloidal oatmeal cream in the management of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in children: a double-blind, randomized, active-controlled study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(7):659–667. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1303569.

- Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, et al. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(1):67–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.251.

- Ullah F, Kaelber DC. Using large aggregated de-identified electronic health record data to determine the prevalence of common chronic diseases in pediatric patients who visited primary care clinics. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(6):1084–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.007.

- Fu T, Keiser E, Linos E, et al. Eczema and sensitization to common allergens in the United States: a multiethnic, population-based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(1):21–26. doi: 10.1111/pde.12237.

- Ait-Khaled N, Odhiambo J, Pearce N, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Africa: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. Allergy. 2007;62(3):247–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01325.x.

- Janumpally SR, Feldman SR, Gupta AK, et al. In the United States, blacks and Asian/Pacific Islanders are more likely than whites to seek medical care for atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(5):634–637. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.5.634.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(4):340–357. doi: 10.1111/exd.13514.

- Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E. Racial differences in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(5):449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.015.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(5):920–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x.

- Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, et al. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.010.

- Proksch E, Fölster-Holst R, Bräutigam M, et al. Role of the epidermal barrier in atopic dermatitis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7(10):899–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07157.x.

- Wilson D, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. In vitro transepidermal water loss: differences between black and white human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(5):647–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03478.x.

- Jungersted JM, Høgh JK, Hellgren LI, et al. Ethnicity and stratum corneum ceramides. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1169–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10080.x.

- Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.008.

- Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, et al. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02539-8.

- Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):152–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.045.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023.

- Van Bever HPS, Llanora G. Features of childhood atopic dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2011;29(1):15–24.

- Allais B, Friedman A. ARTICLE: colloidal oatmeal part I: history, basic science, mechanism of action, and clinical efficacy in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(10):s4–s7.

- Kurtz ES, Wallo W. Colloidal oatmeal: history, chemistry and clinical properties. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(2):167–170.

- Cerio R, Dohil M, Jeanine D, et al. Mechanism of action and clinical benefits of colloidal oatmeal for dermatologic practice. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(9):1116–1120.

- FDA.gov. CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Chapter I, Subchapter D, Part 347 Skin protectant drug products for over-the-counter human use. 2022. [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=347&showFR=1.

- Primus Pharmaceuticals. Epiceram® controlled release skin barrier emulsion. 2018. [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.epiceramrx.com/assets/pdfs/prescribing-information/epiceram-pi.pdf.

- Hanifin J, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;60:44–47. doi: 10.2340/00015555924447.

- Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.002.

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(6):749–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x.

- Nebus J, Wallo W, Fowler J. Evaluating the safety and tolerance of a body wash and moisturizing regimen in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(suppl 2)(2):AB71.

- Nebus J, Nystrand G, Fowler J, et al. A daily oat-based skin care regimen for atopic skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(suppl 1)(3):AB67.

- Weber TM, Babcock MJ, Herndon Jr. JH, et al. Steroid-free emollient formulations reduce symptoms of eczema and improve quality of life. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(5):589–595.

- Adams C, Chatterjee A, Harder BM, et al. Beyond unequal access: acculturation, race, and resistance to pharmaceuticalization in the United States. SSM Popul Health. 2018;4:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.04.003.

- Hebert AA, Rippke F, Weber TM, et al. Efficacy of nonprescription moisturizers for atopic dermatitis: an updated review of clinical evidence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(5):641–655. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00529-9.

- Medicaid.gov. July 2022 Medicaid & CHIP enrollment data highlights. 2022. [cited 2022 Nov 14]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.

- Brooks T, Gardner A. Snapshot of children with Medicaid by race and ethnicity, 2018. 2020. [cited 2022 Nov 14]. Available from: https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Snapshot-Medicaid-kids-race-ethnicity-v4.pdf.

- Kamara M, Kuo AM, Stein SL, et al. Disparities in availability of skin therapies found in public assistance formularies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.033.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):650–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.06.009.