Abstract

Schnitzler syndrome (SchS) is a rare autoimmune and inflammatory disease mediated by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). Recurrent monoclonal gammopathy and chronic urticarial rash are the symptoms required for diagnosis according to the Strasbourg criteria. The low prevalence of this syndrome (around 300 cases have been reported) and confusion with other inflammatory disorders may delay the diagnosis for up to 5 years. Although the most effective treatment for SchS is anakinra, some patients do not respond to this treatment. We report a case of SchS in a 64-year-old woman with multiple episodes of fever, severe rash, erythema, arthralgia and dyspnea. The patient was successfully treated with canakinumab after anakinra intolerance and failure of colchicine, prednisone, methotrexate and dapsone. After the first dose of canakinumab the skin wounds rapidly improved and the patient did not require any concomitant treatments. The cause of SchS is still unknown and a differential diagnosis is recommended, especially with adult-onset Still´s disease due to their similar symptoms. Canakinumab, a specific anti-IL-1β antibody, blocks its binding to receptors, thereby preventing IL-1β-induced gene activation and production of inflammatory mediators. Canakinumab has proven to be an effective drug in SchS, providing an alternative to anakinra.

Introduction

Schnitzler syndrome (SchS) is a rare disorder first described by the French dermatologist Liliane Schnitzler in 1972, where IL-1β plays a key role in its pathophysiology. According to the Strasbourg criteria, recurrent monoclonal gammopathy and chronic urticarial rash are the required symptoms for diagnosis (Citation1). Colchicine, peflacine, corticosteroids and ibuprofen have some efficacy in SchS, although anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, is the most effective treatment (Citation1,Citation2). Recent studies have been developed to evaluate the effectiveness of canakinumab, a specific anti-interleukin-1 beta antibody, however, there is no comparative study between anakinra and canakinumab in SchS (Citation3–5). We report the case of a 64-year-old woman with diagnosis of SchS successfully treated with canakinumab after failure of colchicine, prednisone, methotrexate, dapsone and anakinra.

Case presentation

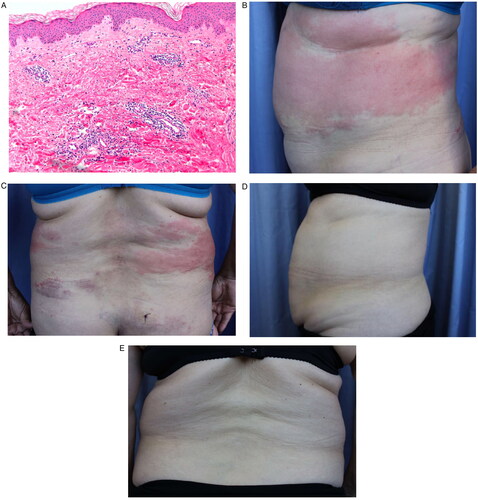

A 64-year-old woman affected by skin rash and a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (small lambda IgG peak) was admitted in October 2009 with fever, severe rash, elevated CRP and dyspnea. In 2011, two episodes of fever, erythema and arthralgia were reported. Although perichondritis was initially considered, all laboratory data resulted negative: electrophysiological study, immunoglobulin, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-SCL-70, extractable nuclear antigens, anti-beta 2 glycoprotein I and anticardiolipin. Two skin biopsies were performed showing a pattern of leukocytoclasia without vasculitis (), thus, methotrexate was prescribed but without any clinical benefit. Afterwards, amyloidosis and Sjögren’s syndrome were considered as possible diagnosis, based on multiple episodes of paresthesia, facial swelling and punctuate keratitis, however, all laboratory parameters were within reference values.

Figure 1. Histopathological pattern of leukocytoclasia without vasculitis. (A) Microscopic observation of leukocytoclasia without vasculitis. Evolution of SchS before and after canakinumab treatment. (B) Skin wounds before canakinumab treatment (side view). (C) Skin wounds before canakinumab treatment (dorsal view). (D) Skin recovery after one dose of canakinumab (side view). (E) Skin recovery after one dose of canakinumab (dorsal view).

In March 2017, the patient was admitted with fever, erythema and myalgia, yet, the computed tomography, chest X-ray and echocardiography did not show signs of disease. In June 2017, methotrexate was prescribed due to clinical suspicion of perichondritis and new facial edema episodes, nevertheless, four months later methotrexate was discontinued and colchicine was started since the patient developed periodic fever.

Between July 2018 and May 2019, the skin wounds extended from the eyelids and cheeks, where they were first noticed, to the abdominal and lumbar regions, accompanied by erythematous plaques, fever and dyspnea (). However, the bronchoscopy, spirometry and cell cultures did not support amyloidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. Throughout these months, the patient received colchicine, prednisone and dapsone without remission of symptoms.

Dermatologists confirmed the diagnosis of SchS according to the Strasbourg criteria (Citation1), therefore, treatment with anakinra 100 mg daily was initiated. However, two weeks later anakinra was increased to 200 mg daily due to another disease outbreak. After four months, the patient developed new skin plaques, thus the dose was reduced to initial prescription. As a result of a disease relapse in November 2019, dermatologists resumed anakinra to 100 mg twice daily, however, this dose induced new injection-site reactions and fever. Considering the persistence of the symptoms, the failure of previous therapies and anakinra intolerance, in February 2020, canakinumab was prescribed (150 mg every 8 weeks). The skin wounds rapidly improved since the first dose of canakinumab (). Throughout this therapy, the patient has not required associated treatments and no adverse events have been observed.

Discussion

SchS is an acquired, rare disease of unknown cause, although most reviews concur that there is an underlying autoimmune and inflammatory factor (Citation1–3). The Strasbourg criteria help clinicians to diagnose SchS on the basis of obligate and minor criteria. Obligate criteria include the presence of a chronic urticarial rash and monoclonal gammopathy while minor criteria include abnormal bone remodeling, neutrophilic dermal infiltrate on skin biopsy and leukocytosis and/or elevated CRP (Citation4). In addition, a differential diagnosis is recommended before considering SchS, especially with adult-onset Still’s disease due to their similar symptoms (Citation6). The low prevalence of this syndrome (around 300 cases have been reported worldwide) and confusion with other inflammatory disorders may delay the diagnosis up to 5 years in many patients (Citation1, Citation7).

Regarding SchS pathophysiology, IL-1β, a proinflammatory cytokine mainly produced by monocytes and macrophages, plays an essential role in the development of SchS (Citation8). Increased levels of IL-1β and interleukin-18, neutrophilia in blood and tissues, recurrent fever, neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis and a genetic predisposition caused by a mutation of NLRP3 gene have been described (Citation7, Citation9).

There is no curative treatment for SchS and conventional therapies, including antihistamines, anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs are usually ineffective (Citation1, Citation7). However, anakinra, canakinumab, tocilizumab and rinolacept are highly effective treatments for SchS. Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, is the current gold standard therapy for SchS, but this drug blocks both IL-1α and IL-1β and its short half-life may reduce adherence since a daily injection is required (Citation5–12). Canakinumab binds to human IL-1β with high affinity and specificity and blocks its binding to receptors, preventing IL-1β-induced gene activation and production of inflammatory mediators. Therefore, canakinumab has been shown to be effective in inducing remission in SchS, providing an alternative to anakinra, which can be administered every 8 weeks due to its long half-life (Citation13–19).

In reviewing the available literature, the treatment of SchS with anakinra is usually effective (). However, patients refractory to anakinra may improve with canakinumab due to its higher specificity (Citation16,Citation17). Despite the evidence of efficacy using IL-1 blocking drugs, our patient did not show any improvement even with high doses of anakinra. Therefore, we think that until clinical studies are available to support it, canakinumab can be considered as a valid treatment in those patients who have failed to conventional therapy for SchS.

Table 1. Summary of patient characteristics with diagnosis of Schnitzler syndrome.

In conclusion, IL-1 blocking drugs are the most effective therapies in SchS. Although anakinra is the most commonly used agent in the treatment of SchS and was recommended as of first-line treatment by an expert consensus conference in 2012, canakinumab treatment is an optional therapy in refractory cases (Citation11, Citation17).

Additional contributions

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

Author access to data

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Authors’ contributions

MDF and NST were involved in the diagnosis and management of the patient. SGM reviewed the literature. ALSM drafted the original manuscript and coordinated the study. PCR and BGD carried out the final editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compensation

The authors declare that no other person has made a substantial contribution to this manuscript. Nevertheless, we thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.

Patient consent for publication

The informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Previous presentation of the information reported in the manuscript

The authors declare that this paper is original and has not been previously published or is in the process of being reviewed by any other journal.

Sources of funding and support

This manuscript has been performed without receiving funding nor grants, consultancies, honoraria or payment, speakers’ bureaus, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, donation of medical equipment, or patents planned, pending or issued.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships and affiliations with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Simon A, Asli B, Braun-Falco M, et al. Schnitzler’s syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Allergy. 2013;68(5):1–4. doi: 10.1111/all.12129.

- Lipsker D. The schnitzler syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-38.

- Rowczenio DM, Pathak S, Arostegui JI, et al. Molecular genetic investigation, clinical features and response to treatment in 21 patients with schnitzler syndrome. Blood. 2018;131(9):974–981. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-810366.

- De Koning HD, Schalkwijk J, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, et al. Sustained efficacy of the monoclonal anti-interleukin-1 beta antibody canakinumab in a 9-month trial in schnitzler’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1634–1638. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202192.

- Krause K, Tsianakas A, Wagner N, et al. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in schnitzler syndrome: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.041.

- Rossi-Semerano L, Fautrel B, Wendling D, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of off-label anti-interleukin-1 treatments in France: a nationwide survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10(10):19. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0228-7.

- Gusdorf L, Lipsker D. Schnitzler syndrome: a review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(8):46. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0673-5.

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612.

- Loock J, Lamprecht P, Timmann C, et al. Genetic predisposition (NLRP3 V198M mutation) for IL-1-mediated inflammation in a patient with schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):500–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.066.

- Martínez-Taboada VM, Fontalba A, Blanco R, et al. Successful treatment of refractory schnitzler syndrome SchS with anakinra: comment on the article by hawkings et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2226–2227. doi: 10.1002/art.21101.

- Néel A, Henry B, Barbarot S, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in schnitzler’s syndrome: a french multicenter study. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(10):1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.031.

- Gouveia AI, Micaelo M, Pierdomenico F, et al. Schnitzler síndrome: a dramatic response to anakinra. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6(2):299–302. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0108-7.

- Betrains A, Staels F, Vanderschueren S. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab treatment in schnitzler syndrome: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(4):636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.002.

- Vanderschueren S, Knockaert D. Canakinumab in schnitzler syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42(4):413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.06.003.

- Krause K, Bonnekoh H, Ellrich A, et al. Long-term efficacy of canakinumab in the treatment of schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1681–1686.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.909.

- de Koning HD. Schnitzler’s syndrome: lessons from 281 cases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4(4):41. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-4-41.

- Gellrich FF, Günther C. Schnitzler syndrome. Hautarzt. 2019;5 doi: 10.1007/s00105-019-4434-4.

- Pesek R, Fox R. Successful treatment of schnitzler syndrome with canakinumab. Cutis. 2014;94(3):E11–2.

- Thomsen SF, Duhn PH, Kristensen J. A 51-Year old woman with schnitzler syndrome treated with canakinumab. Open Dermatol J. 2011;5:31–32.