Abstract

Background

Real-world data on the effectiveness of systemic therapy in atopic dermatitis (AD) are limited.

Methods

Adult patients with AD in the CorEvitas AD registry (2020–2021) who received systemic therapies for 4–12 months prior to enrollment were included based on disease severity: body surface area (BSA) 0%–9% and BSA ≥10%. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics. Pairwise effect sizes (ES) were used to compare BSA groups.

Results

The study included 308 patients (BSA 0%–9%: 246 [80%]; BSA ≥10%: 62 [20%]). Despite systemic therapy, both BSA groups reported the use of additional topical therapy and the presence of lesions at difficult locations. Moderate-to-severe AD (vIGA-AD®) was reported by 11% (BSA 0%–9%) and 66% (BSA ≥10%; ES = 0.56) of patients. Mean disease severity scores: total BSA (2% and 22%; ES = 3.59), EASI (1.1 and 11.1; ES = 2.60), and SCORAD (12.1 and 38.0; ES = 1.99). Mean scores for PROs: DLQI (3.7 and 7.5; ES = 0.75), and peak pruritus (2.2 and 4.5; ES = 0.81). Inadequate control of AD was seen in 27% and 53% of patients (ES = 0.23).

Conclusions

Patients with AD experience a high disease burden despite systemic treatment for 4–12 months. This study provides potential evidence of suboptimal treatment and the need for additional effective treatment options for AD.

KEY POINTS

This real-world study assessed clinical characteristics and overall disease burden in adult patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) who were receiving systemic therapy for 4–12 months.

Patients reported greater involvement of back and anterior trunk, and lesions at difficult locations. Irrespective of body surface area involvement, patients continued to experience inadequate control of AD, varied disease severity, and impact on quality of life.

The study provides potential evidence of suboptimal treatment and the need for effective treatment options for the management of AD. Besides clinical outcomes, treating dermatologists and dermatology practitioners should include patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical care to determine the best treatment options for their patients.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythematous plaques, intense itch, and skin pain (Citation1,Citation2). The estimated prevalence of AD ranges from 2% to 7% in the United States (US) adult population (Citation3–6), with ∼40% of patients being affected by moderate-to-severe disease (Citation3,Citation7,Citation8). Variations in the intensity of AD symptom presentation, including number of lesions and total surface area of skin affected, lead to differences in disease burden reported among patients (Citation9,Citation10).

The treatment recommendations for AD are based on the age and severity of the disease. Current AD management guidelines have highlighted the significant variability in treatment patterns among patients with AD (Citation11–14). For the management of moderate-to-severe AD, the guidelines recommend using systemic therapies, such as immunosuppressants (cyclosporine, azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil), systemic corticosteroids, and approved biologics and Janus kinase inhibitors (Citation11–14).

Patients with moderate-to-severe AD can be treated with biologic or non-biologic systemic agents, either alone or in combination. However, limited information is available about clinical characteristics and overall disease burden in patients following continued treatment with systemic therapy in a real-world setting. The current study, using the CorEvitas AD registry, was designed to describe clinical characteristics and disease burden in patients with AD who received systemic therapy for at least 4–12 months.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study conducted using data from the CorEvitas AD registry between 21 July 2020 and 30 September 2021. Adult (≥18 years old) patients diagnosed with AD by a dermatologist or a qualified dermatology practitioner and who were willing to provide personal information were included in the study. In addition, patients had to fulfill any one of the following three inclusion criteria: (i) initiated a new eligible systemic medication within 12 months prior to enrollment, (ii) were prescribed a new eligible systemic medication at the enrollment visit, or (iii) were not being treated with an eligible systemic medication at enrollment but had an Eczema Area Severity Index score (EASI) ≥12 AND a vIGA-AD® score ≥3. Eligible systemic medications included (i) biologics (dupilumab and other biologics prescribed off-label for AD, such as secukinumab, ustekinumab, risankizumab, ixekizumab, and omalizumab); (ii) small molecules prescribed off-label for AD (baricitinib, apremilast, upadacitinib, montelukast, and tofacitinib); and (iii) non-biologics prescribed off-label for AD (azathioprine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, and tacrolimus (Citation15)). All eligible patients receiving systemic therapy for 4–12 months at the time of enrollment were included in the study and were stratified into two disease severity groups based on their body surface area (BSA) involvement (Citation16): BSA 0%–9% and BSA ≥10%.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPPs) (Citation17) and the applicable laws and regulations of the country or countries where the study was being conducted, as appropriate.

Data source

The CorEvitas AD registry is a prospective, non-interventional registry for patients with AD under the care of a dermatologist or a qualified dermatology practitioner. As of 30 September 2021, the registry included 1439 patients from 57 private and academic clinical sites with 116 providers across 31 states in the US and four provinces in Canada. A structured and standardized data collection method was used to collect longitudinal data from both patients and their treating dermatologists during routine clinical visits.

Study outcomes and assessments

The primary objectives were to (i) describe patient characteristics, clinical characteristics, and disease burden stratified by BSA groups; and (ii) descriptively compare patient characteristics at the time of enrollment across BSA groups. All study variables were captured at the time of enrollment visit.

Patient characteristics

Variables assessed included sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, history of comorbidities, and AD disease characteristics.

AD treatment and clinical characteristics

Treatment characteristics included current/concomitant therapies (drug initiated/prescribed at enrollment) and prior drug therapies (history at enrollment). Clinical characteristics included sites of AD involvement and difficult locations.

Disease severity

Disease severity was assessed using vIGA-AD (range: 0 being ‘clear skin’ to 4 being ‘severe disease’) (Citation18); total BSA involvement (range: 0%–100%); EASI (range: 0–72) (Citation19); SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD; range: 0–103) (Citation20); and a visual analog scale (VAS on a 100 mm scale; range: 0 being ‘clear/none’ to 100 being ‘severe abnormalities’) for overall severity of nail changes. A detailed description of disease severity measures is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) included the global assessment of AD severity (symptoms rated as clear, almost clear, mild, moderate, or severe over the past 24 h); health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; range: 0–30) (Citation21); peak pruritus in past 24 h using numeric rating scale (NRS range: 0 being ‘no itch’ to 10 being ‘worst-itch imaginable’) (Citation22) and the AD Control Tool (ADCT; range: 0–24) (Citation23). The recall period for DLQI and ADCT outcomes was over the past week. Higher DLQI scores indicate greater HRQoL impairment (Citation21). An ADCT score of ≥7 was used as the threshold to identify patients ‘not in control’ (Citation23). A detailed description of PRO measures is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

This study was descriptive and did not have a priori hypotheses. All study variables were summarized using descriptive statistics for the overall cohort, and by BSA groups (0%–9% and ≥10%). Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables were reported as counts and proportions. To ensure patient confidentiality, no statistics for counts <5 were reported. Between-group differences (BSA 0%–9% vs. BSA ≥10%) were evaluated using pairwise effect sizes (ES): Cohen’s d for continuous variables, and Cohen’s w for categorical variables. For Cohen’s d, the thresholds for small, medium, and large differences were 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively; for Cohen’s w, these were 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, respectively (Citation24,Citation25). All analyses were conducted using Stata Release 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient population

The registry enrolled 1500 patients between 21 July 2020 and 30 September 2021. Of these, 308 patients were receiving an eligible systemic medication for 4–12 months and comprised the study cohort (Supplementary Figure 1). The majority (80%; n = 246) of patients had BSA involvement of 0%–9% at enrollment, with BSA involvement of ≥10% in 20% (n = 62) of patients.

Patient demographics, lifestyle, and disease characteristics at enrollment were similar between the two BSA groups (). In the overall cohort, mean (SD) estimated age at AD onset was 30.5 (24.1) years, and mean (SD) duration of AD was 18.9 (18.5) years. Similar to BSA involvement, 78% (n = 240) of patients had clear-to-mild AD (vIGA-AD 0–2), while 22% (n = 68) had moderate-to-severe AD (vIGA-AD 3–4). The majority of patients in the BSA 0%–9% (59%) and BSA ≥10% (74%) groups reported symptoms throughout the year (ES = 0.14).

Table 1. Patient demographics, lifestyle, and disease characteristics at enrollment, stratified by BSA.

Treatment characteristics

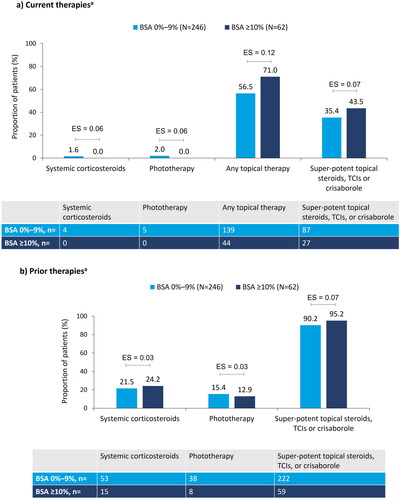

Although all of the patients in this cohort were receiving eligible systemic therapy for 4–12 months (), the majority with BSA 0%–9% (n = 139, 57%) and BSA ≥10% (n = 44, 71%) were using additional topical therapy (ES = 0.12; ). Current concomitant use of systemic corticosteroids (ES = 0.06), phototherapy (ES = 0.06), and super-potent topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or topical crisaborole (ES = 0.07) was similar between the two BSA groups (). Prior therapy use was consistent (ES range: 0.03–0.07) between the two BSA groups ().

Figure 1. Treatment characteristics at enrollment, stratified by BSA: (a) current therapiesa; (b) prior therapiesa. aNot mutually exclusive. Pairwise ES for between-group differences were calculated using Cohen’s w using thresholds of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, for small, medium, and large differences, respectively. AD: atopic dermatitis; BSA: body surface area; ES: effect size; TCI: topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Clinical characteristics

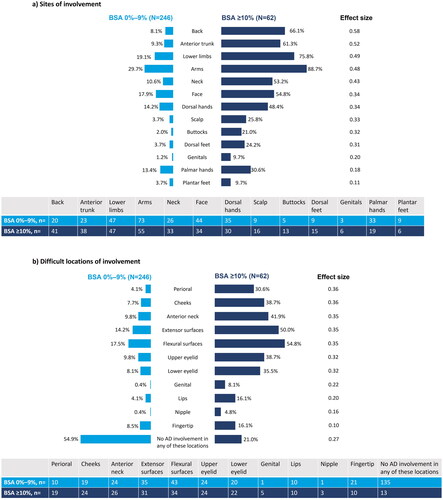

Despite treatment with systemic therapy, involvement of the back (ES = 0.58) and anterior trunk (ES = 0.52) was observed in the BSA 0%–9% (8% and 9%) and BSA ≥10% (66% and 61%) groups, respectively. Other sites of involvement included the lower limbs, arms, neck, face, dorsal hands, scalp, buttocks, and dorsal feet (ES range: 0.31–0.49; ). Patients in the BSA 0%–9% and BSA ≥10% groups reported lesions in difficult locations (ES range: 0.32–0.36): perioral (4% and 31%), cheeks (8% and 39%), anterior neck (10% and 42%), extensor surfaces (14% and 50%), flexural surfaces (17% and 55%), upper eyelid (10% and 39%), and lower eyelid (8% and 35%) ().

Figure 2. Clinical characteristics of AD at enrollment, stratified by BSA: (a) sites of involvement; (b) difficult locations of involvement. Pairwise effect sizes for between-group differences were calculated using Cohen’s w using thresholds of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 for small, medium, and large differences, respectively. AD: atopic dermatitis; BSA: body surface area.

Disease severity

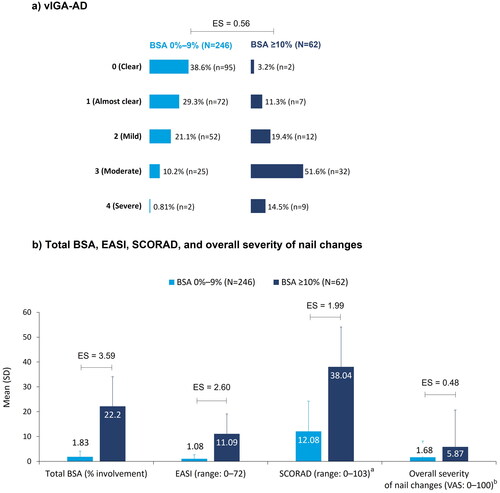

Assessment of AD severity by vIGA-AD showed moderate-to-severe disease in 11% (n = 27) of patients in the BSA 0%–9% group and 66% (n = 41) of patients in the BSA ≥10% group, while on systemic therapy (ES = 0.56; ). Varied disease severity (ES range: 1.99–3.59) was observed in the two BSA groups when assessed using total BSA involvement (mean ± SD: 2% ± 2.3 and 22% ± 11.9), EASI (mean ± SD: 1.1 ± 1.6 and 11.1 ± 8.0), and SCORAD (mean ± SD: 12.1 ± 12.2 and 38.0 ± 16.0), respectively ().

Figure 3. AD disease severity at enrollment, stratified by BSA: (a) vIGA-AD; (b) Total BSA, EASI, SCORAD, and overall severity of nail changes. aBSA 0%–9%: N = 245; bBSA 0%–9%: N = 243, BSA ≥10%: N = 61. Pairwise ES for between-group differences were calculated using Cohen’s w for vIGA-AD and Cohen’s d for total BSA (% involvement), EASI, SCORAD, and overall severity of nail changes. The thresholds for small, medium, and large differences were 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, respectively, for Cohen’s w and 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively, for Cohen’s d. AD: atopic dermatitis; BSA: body surface area; EASI: Eczema Area Severity Index; ES: effect size; SCORAD: SCORing AD; SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analog scale; vIGA-AD: validated Investigator Global Assessment for AD.

Patient-reported outcomes

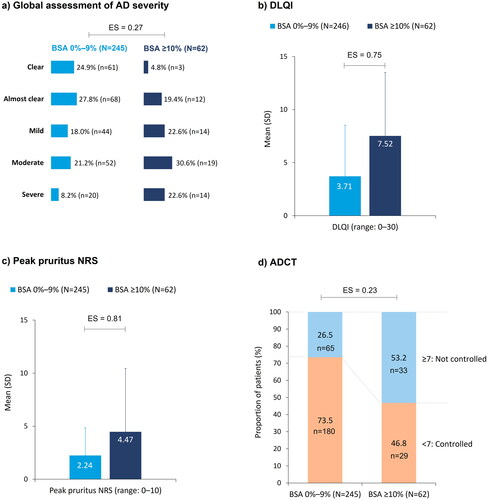

Even with 4–12 months of systemic therapy, global assessment of AD severity showed that 29% (n = 72; BSA 0%–9%) and 53% (n = 33; BSA ≥10%) of patients felt they had moderate-to-severe AD (ES = 0.27; ). Mean (SD) DLQI scores were 3.7 (4.8) and 7.5 (6.0) in the BSA 0%–9% and BSA ≥10% groups, respectively (ES = 0.75; ). Mean (SD) peak pruritus scores were 2.2 (2.6) in the BSA 0%–9% group and 4.5 (3.2) in the BSA ≥10% group (ES = 0.81; ). Inadequate control of AD despite systemic treatment was reported by 27% (n = 65) of patients in the BSA 0%–9% group and 53% (n = 33) of patients in the BSA ≥10% group (ES = 0.23; ).

Figure 4. Patient-reported outcomes at enrollment, stratified by BSA: (a) global assessment of AD severity; (b) DLQI; (c) peak pruritus NRS; (d) ADCT. Pairwise ES for between-group differences were calculated using Cohen’s w for global assessment of AD severity and ADCT, and Cohen’s d for DLQI and peak pruritus. The thresholds for small, medium, and large differences were 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, respectively, for Cohen’s w and 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively, for Cohen’s d. AD: atopic dermatitis; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; BSA: body surface area; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; ES: effect size; NRS: numeric rating scale; SD: standard deviation.

Discussion

In this real-world study, a high disease burden was observed in patients with AD despite systemic therapy for 4–12 months. Patients in both BSA groups reported moderate-to-severe disease (vIGA-AD: 3–4), inadequate control of AD (ADCT score ≥7), and impact on QoL. Patients showed lesions in multiple areas, however, the greatest differences were noted in the proportion of patients who reported lesions on the back and anterior trunk between the two BSA groups. Patients also had lesions at difficult and/or prominent areas including the perioral region, cheeks, anterior neck, extensor and flexural surfaces, and upper and lower eyelids.

In addition to systemic therapy, patients were receiving topical therapy, systemic corticosteroids, and phototherapy in both BSA groups. Similar to other real-world studies, the findings in our study vary from clinical trial data; even with systemic therapies, loss of response and patient dissatisfaction is prevalent in real-world settings (Citation26,Citation27). This could be attributed to several factors, such as age, poor treatment compliance, adverse events, incorrect treatment choices, complexity of treatment regimens, and frequency of AD-related follow-up visits (Citation26–29).

Our data showed the involvement of multiple areas, including lesions in areas difficult to treat. The heterogeneous distribution of AD lesions and involvement of multiple locations was reported previously in the US population (Citation9,Citation10,Citation30). In a real-world study that assessed the impact of lesion location on QoL, patients with lesions in visible areas had a profound impact on their QoL and reported experiencing anxiety and depression (Citation30).

As indicated by total BSA involvement, high disease burden and apparent modest skin clearance suggest undertreatment in patients with AD. PROs help monitor disease burden and treatment response from patients’ perspective. The current study focused on assessing PROs in patients receiving continued systemic therapy. Although the majority (80%) of patients had BSA involvement of 0%–9% at enrollment, they continued to experience disease symptoms and impact on HRQoL. In addition to clinical outcomes, treating dermatologists and dermatology practitioners should include the perspective of patients in routine clinical care for determining the best treatment options for their patients (Citation31–33).

In our study, inadequate control of AD was reported by more than one-fourth of the patients in the BSA 0%–9% group and by more than half of the patients in the BSA ≥10% group. As reported previously, inadequate disease control is common in most patients with moderate-to-severe disease (Citation31,Citation32). This could be due to the limited approved treatment options available for AD, heterogenous nature of the disease, and different unmet needs in patients with AD. This study highlights the need for more effective and tailored treatment options for the management of AD.

The study results should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. The sample population included in the registry is not fully representative of all adults with AD in the US and Canada. Medication history prior to enrollment was derived from data provided by the patients and their current providers. New treatments approved for moderate-to-severe AD after the study period were not included in this data assessment. The ‘cause’ of visits to the dermatologists was not captured, assuming that the visit is ‘AD related.’ Since the registry is not based on an inception cohort, patients may be unable to recall their entire medication history, leading to misclassification.

In conclusion, despite treatment with systemic therapy for 4–12 months, patients with AD continue to experience a high disease burden, providing potential evidence of suboptimal treatment among this clinically meaningful subgroup of patients. This study highlights an existing unmet need for more effective and targeted treatment options for the management of AD.

Ethical approval

The study was performed following Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPPs). All participating investigators were required to obtain full board approval for conducting noninterventional research involving human subjects with a limited dataset. Sponsor approval and continuing review was obtained through a central Institutional Review Board (IRB), the New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB; no. 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, full board approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to CorEvitas, LLC prior to the initiation of any study procedures. All patients in the registry were required to provide written informed consent and authorization prior to participating.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with GPPs and the applicable laws and regulations of the country or countries where the study was being conducted, as appropriate.

Author contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Jonathan I. Silverberg: Data collection, data analysis, and editing of publication.

Evangeline Pierce: Conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Meghan Feely: Data analysis and editing of publication.

Amber Reck Atwater: Data analysis and editing of publication.

Amy Schrader: Design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Eric A. Jones: Conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and drafting and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Swapna S. Dave: Interpretation of data for the work and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Eric L. Simpson: Interpretation of data for the work and critical revision of the work for important intellectual content.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (179.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the investigators, their clinical staff, and patients who participated in the CorEvitas Atopic Dermatitis Registry. The authors thank Moksha Shah of Eli Lilly Services India Private Limited, Bengaluru, India, for providing medical writing support.

Disclosure statement

Jonathan I. Silverberg: Honoraria as a consultant and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Alamar, Aldena, Amgen, AObiome, Arcutis, Arena, Asana, Aslan, BioMX, Biosion, Bodewell, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara, Castle Biosciences, Celgene, Connect Biopharma, CorEvitas, Dermavant, Dermtech, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Kiniksa, Leo Pharma, My-Or Diagnostics, Nektar, Novartis, Optum, Pfizer, RAPT, Recludix, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, Shaperon, TARGET-RWE, Union, UpToDate; speaker for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme; institution received grants from Galderma, Incyte, Pfizer.

Evangeline Pierce: Employment and stockholder, Eli Lilly and Company.

Meghan Feely: Associate staff member, Mount Sinai Hospital; current employment and shareholder, Eli Lilly and Company; consulting, travel, or speaker fees, American Academy of Dermatology, Aerolase, Castle Biosciences, CeraVe – L’Oréal, DREAM USA, Galderma Aesthetics, Glow Recipe, La Roche-Posay-L’Oréal, Revian, Sonoma Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma, and Suneva Medical.

Amber Reck Atwater: Employment and stockholder, Eli Lilly and Company; Pfizer Independent Learning and Change Grant (for fellow salary support; ended 5/2021); Patents planned, issued or pending, Eli Lilly and Company; President (2019–2021), American Contact Dermatitis Society (Board); Immediate Past President (2021–2023), American Contact Dermatitis Society (Board); Associate Editor, Contact Dermatitis, Dermatitis Journal (Board); Associate Editor, Cutis Journal (Board).

Amy Schrader: Employment, CorEvitas LLC, MA, USA.

Eric A. Jones: Former employment, CorEvitas LLC, MA, USA. Work related to the study was performed during his tenure at CorEvitas.

Swapna S. Dave: Former employment, CorEvitas LLC, MA, USA. Work related to the study was performed during her tenure at CorEvitas.

Eric Simpson: Grants/Research/Investigator (payments to OHSU), Kyowa HakkoKirin Pharma, Inc., AbbVie, Leo Pharma Inc., Merck, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer Inc., Novartis, Regeneron, Galderma Laboratories, LP, Sanofi, Incyte Corporation, Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc., Amgen, Arcutis Inc, ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, Castle Biosciences, CorEvitas, Dermavant Sciences Inc, Dermira, National Jewish Health, Sanofi Genzyme, Target RWE, Arcotech Biopharma Inc, Kymab; Consulting fees (self), Boehringer Ingelheim, Forte Biosciences, Incyte Corporation, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Leo Pharma Inc., Dermira, Benevolent AI Bio Limited, Excerpta Medica B.V., Pierre Fabre, Roivant Sciences, Trevi Therapeutics, ASLAN, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, BiomX Ltd., Bluefin Biomedicine, Coronado Biosciences, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma Inc., Medscape, Ortho Dermatologics, Boston Consulting Group, Evidera, Collective Acumen LLC, Advances in Cosmetic Medical Derm Hawaii LLC, AOBiome, LLC, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CorEvitas, Evelo Biosciences, Inc., Gesellschaft Z, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Physicians World LLC, WebMD, Med Learning Group, MJH Holding Company Inc.; Honoraria (self), AbbVie, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Leo, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Medscape; Lecture fees (self), FIDE, Prime Education, Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis, Vindico Medical Education, Maui Derm; Reimbursement or travel costs cover (self), FIDE, Maui Derm, Sanofi-Regeneron; Advisory board (self), Merck, Arena Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Leo, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi; Honorarium, Chair of Sanofi-Genzyme and Regeneron US Medical Advisory Board; Chair of Research, Scientific Advisory Committee of the National Eczema Association; Chair of Atopic Dermatitis Expert Resource Group for the AAD; Board Member, International Society for Atopic Dermatitis (ISAD); Executive Member for the international Harmonizing Outcome Measures in Eczema (HOME) Working Group.

Data availability statement

Data are available from CorEvitas, LLC through a commercial subscription agreement and are not publicly available. No additional data are available from the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z.

- Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, et al. Burden of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(6):548–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.09.076.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(3):583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028.

- Harrop J, Chinn S, Verlato G, et al. Eczema, atopy and allergen exposure in adults: a population-based study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(4):526–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02679.x.

- Sacotte R, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of adult atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.05.007.

- Hadi HA, Tarmizi AI, Khalid KA, et al. The epidemiology and global burden of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Life. 2021;11(9):936. doi: 10.3390/life11090936.

- Chan LN, Magyari A, Ye M, et al. The epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in older adults: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. PLOS One. 2021;16(10):e0258219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258219.

- Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73(6):1284–1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401.

- Silverberg JI, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, et al. Distribution of atopic dermatitis lesions in United States adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(7):1341–1348. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15574.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657–682. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14891.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based european guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888.

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, et al. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of the joint task force practice parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):S49–S57. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.009.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717–2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892.

- Keaney TC, Bhutani T, Sivanesan P, et al. Open-label, pilot study examining sequential therapy with oral tacrolimus and topical tacrolimus for severe atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.033.

- Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1519–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.005.

- Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):2–10.

- Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, et al. The validated investigator global assessment for atopic dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.104.

- Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI evaluator group. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x.

- Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186(1):23–31.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x.

- Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, et al. Peak pruritus numerical rating scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):761–769. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17744.

- Pariser DM, Simpson EL, Gadkari A, et al. Evaluating patient-perceived control of atopic dermatitis: design, validation, and scoring of the atopic dermatitis control tool (ADCT). Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(3):367–376. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1699516.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1988.

- Ellis PD. The essential guide to effect sizes: statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Wu JJ, Lafeuille M-H, Emond B, et al. Real-world effectiveness of newly initiated systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis in the United States: a claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2022;39(9):4157–4168. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02197-z.

- Augustin M, Costanzo A, Pink A, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and treatment benefits among adult patients with atopic dermatitis: results from the atopic dermatitis patient satisfaction and unmet need survey. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00830. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.3932.

- Johnson BB, Franco AI, Beck LA, et al. Treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:181–192. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S163814.

- Sokolova A, Smith SD. Factors contributing to poor treatment outcomes in childhood atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56(4):252–257. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12331.

- Lio PA, Wollenberg A, Thyssen JP, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis lesion location on quality of life in adult patients in a real-world study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(10):943–948. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.5422.

- Bruin-Weller M, Pink AE, Patrizi A, et al. Disease burden and treatment history among adults with atopic dermatitis receiving systemic therapy: baseline characteristics of participants on the EUROSTAD prospective observational study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(2):164–173. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1866741.

- Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Margolis DJ, et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(8):903–912. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1572.

- Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.004.