Dear Editor,

Although the nails show lichenoid involvement in 25% of patients with lichen planus, isolated nail lichen planus (NLP) is rare, with no accurate epidemiologic figures (Citation1). Depending on whether the nail matrix or bed is affected, the clinical picture will differ. Commonly, the nail matrix is affected, which is followed by lateral thinning with longitudinal ridging and fissuring of the nail. In severe and longstanding NLP, dorsal pterygium formation might occur as a result of nail matrix damage that can promote permanent scarring and functional impairment. When the nail bed is affected, it is followed by subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, splinter hemorrhage, or even anonychia (Citation2). NLP may cause significant morbidity, and it is one of the few nail diseases in which permanent nail scarring ensue with inadequate treatment (Citation3). The diagnosis of NLP can be reached clinically in most cases, but where there is clinical uncertainty, histopathology of the nail, demonstrating all the classic lichenoid findings, is usually conclusive. In this article, we presented a case of refractory isolated NLP that improved with Baricitinib. As we know, this is the first reported case of NLP, with a clear pathological diagnosis, treated with Baricitinib.

Case report

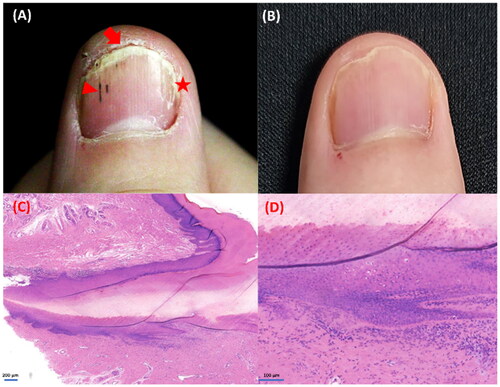

A man in his 30s was admitted to our medical center complaining of intolerable onychorrhexis of most of his fingernails that started 2 years ago. Typical sings of longitudinal ridging, splitting, pitting, onychoschizia, onycholysis, splinter hemorrhage and subungual hyperkeratosis can we see in . No other dermatologic lesions were noted on physical examination. Onychomycosis was ruled out by direct examination as well as results of a culture of nail specimens. A diagnosis of NLP was confirmed by longitude biopsy from the left middle fingernail, and histological findings showed a mainly lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate around the matrix and the eponychium, with focal hypergranulosis and vacuolar degeneration of basal cells that were consistent with the diagnosis of NLP (). His NLP was previously treated with topical glucocorticoid encapsulation therapy for 6 months, but efficacy of topical medications was limited and it had a negative impact on his daily programming work. Then, the patient was switched to treatment with oral acitretin, 20 mg, daily. However, he could not tolerate the side effects caused by oral acitretin, such as severe dry and chapped lips. So oral administration was stopped after 4 weeks later. Because of concerns about the cascade of side effects of glucocorticoids, the patient refused systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Finally, the patient’s dermatologist administered baricitinib, 4 mg, daily for him. After 2 months of treatment, his nails showed consistent improvement, after 6 months they were completely clear (). Besides, drastic improvement was observed in DLQI, which reduced from 20/30 to 5/30. After that, the daily dose was reduced to 2 mg. In the follow-up of nearly one year, the patient remained satisfied with his disease control and no adverse events or laboratory abnormalities was observed.

Figure 1. The clinical manifestations of the patient and histopathology of the nail biopsy: (A) the appearance of right fingernail before treatment, we can see typical sings of longitudinal ridging, splitting (star), onychoschizia, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis (arrow) and splinter hemorrhage (triangle). (B) Complete clearance after 6 months of treatment with baricitinib, 4 mg, daily. (C–D) The biopsy specimen showing a band of lymphocytes infiltrate around the matrix and the eponychium, with focal hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, vacuolar basal cell degeneration and lack of spongiosis. Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×50 and ×200, respectively.

Discussion

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology that may affect the skin, mucosae, scalp, and nails. Nail lichen planus (NLP) may occur independently or in conjunction with other forms of LP (Citation3). When the nails are affected, it may lead to permanent destruction with severe functional and psychosocial consequences. For many patients with NLP, there is a profound impact on daily activities and quality of life. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and early treatment are essential, even in mild cases (Citation3).

Potent topical steroids under occlusive dressings are the preferred first-line topical treatment. Due to the poor short-term efficacy and may cause long-term side effects, intralesional and intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide should be considered as further first-line therapies. Oral retinoids are second-line choices, and immunosuppressive agents may also be considered (Citation4). However, treatment of NLP is notoriously difficult with high rates of therapeutic failures or relapses.

The patient presented herein was initially treated with topical glucocorticoid encapsulation therapy, which was considered as the first-line topical therapy. After 6 months of treatment, the patient received limit remission. Because of the adverse effects of acitretin and reluctance to use glucocorticoids therapy systematically, the patient was eventually converted to JAK1/2 inhibitor Baricitinib. His disease was substantially improved with baricitinib (4 mg daily) after two months and completely clear after six months. Inhibition of JAKs has been shown to be effective in various skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata (Citation5). Until now, several publications have reported administering JAK inhibitor to improve LP, also its variants (Citation6–11). To the best of our knowledge, only 2 cases of NLP treated with JAK inhibitor were reported in the PubMed database. Details of all reports of NLP to date, including our case, are described in .

Table 1. JAK inhibitor for NLP cases reported to date.

The efficacy of Baricitinib for LP could be explained by the inhibition of the JAK1/2-STAT pathways, which is considered the cornerstone of the pathogenesis of LP (Citation12,Citation13). Shao et.al (Citation12) has demonstrated that IFN-γ could prime keratinocytes and increase their susceptibility to CD8+ T cell–mediated cytotoxic responses through MHC class I induction in a coculture model, and this process is dependent on JAK2/STATA1 signaling. And JAK1/2 inhibitor Baricitinib fully protects keratinocytes against cell-mediated cytotoxic responses in vitro. With the consequent suppression of the interferon-γ–mediated signaling and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte recruitment, the inflammation of lichen planus can also be alleviated and controlled.

Conclusion

Because of the key role of the INF–γ pathway in LP pathogenesis, inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway is a therapeutic target for LP. Although the clinical manifestation of the patient was mild, the pain caused by onychorrhexis posed great impact on his daily life, and NLP is irreversible, aggressive treatment is necessary. In our case, we can see that NLP was well controlled following treatment with baricitinib without any adverse effects. We conclude that Baricitinib could open a new therapeutic window for NLP, with clinical studies warranted to evaluate their efficacy.

Thanking patient participants

The authors thank the participants of the study.

Ethical approval

The authors certify that all necessary patient consent forms have been obtained. Written informed consent for publication of their details was obtained from the patient and was compliant with the Hospital.

Author contributions

Juan He wrote this article. Tengyu Weng contributed to the medical care and collected case data. Wenwei Zhu conducted the biopsy and pathological analysis. Yi Yang and Chengxin Li edited and corrected the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):1–3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.010.

- Goettmann S, Zaraa I, Moulonguet I. Nail lichen planus: epidemiological, clinical, pathological, therapeutic and prognosis study of 67 cases: nail lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(10):1304–1309. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04288.x.

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(2):221–230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002.

- Boch K, Langan EA, Kridin K, et al. Lichen planus. Front Med. 2021;8:737813. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.737813.

- Solimani F, Meier K, Ghoreschi K. Emerging topical and systemic JAK inhibitors in dermatology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2847. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02847.

- Yang CC, Khanna T, Sallee B, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of lichen planopilaris: a case series. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(6):e12656. doi:10.1111/dth.12656.

- Seiringer P, Lauffer F, Pilz A, et al. Tofacitinib in hypertrophic lichen planus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(14):adv00220. doi:10.2340/00015555-3585.

- Plante J, Eason C, Snyder A, et al. Tofacitinib in the treatment of lichen planopilaris: a retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1487–1489. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.104.

- Damsky W, Wang A, Olamiju B, et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1708–1710.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.031.

- Iorizzo M, Haneke E. Tofacitinib as treatment for nail lichen planus associated with alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(3):352–353. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4555.

- Pünchera J, Laffitte E. Treatment of severe nail lichen planus with baricitinib. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(1):107–108. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5082.

- Shao S, Tsoi LC, Sarkar MK, et al. IFN-γ enhances cell-mediated cytotoxicity against keratinocytes via JAK2/STAT1 in lichen planus. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(511):eaav7561. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aav7561.

- Di Lernia V. Targeting the IFN-γ/CXCL10 pathway in lichen planus. Med Hypotheses. 2016;92:60–61. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2016.04.042.