Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes itching, skin lesions, and negatively affects one’s quality of life.

From a pathophysiological perspective, AD is intricate, involving genetic predisposition and environmental triggers as significant factors. Mechanistically, these elements can lead to compromised epidermal barrier function, irregularities in the skin microbiome, and a predominant type-2 immunity-based skewed immune response. Specifically, interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of chronic itch by contributing to the initiation and perpetuation of a T-helper 2 subset, the primary cellular subpopulation implicated in the development of chronic pruritus in AD (Citation1). Supporting this, the targeting and blocking of IL-4 and IL-13 molecules have shown significant efficacy in treating AD, particularly in rapidly improving associated symptoms such as chronic itching (Citation1–2). Furthermore, moderate-to-severe AD has a detrimental impact on both physical and mental health, correlating with an increased incidence of anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders. Once again, dupilumab has demonstrated efficacy in alleviating these symptoms (Citation3–4). Biologic therapies have proven crucial in the long-term management of pruritus associated with conditions like atopic dermatitis. Not only do these therapies effectively address chronic itch, but their demonstrated good safety profile adds to their significance in providing sustained relief for patients over an extended duration.

Tralokinumab is a high-affinity human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the binding of the IL-13 cytokine to its receptor. In the phase-3 trials (ECZTRA 1, 2, and 3), tralokinumab demonstrated significant improvements in primary outcomes, achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score reductions of at least 75% (EASI-75) and Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 0/1 at specific time points, signifying its effectiveness in treating moderate-to-severe AD in adults (Citation5–6). Furthermore, all three trials consistently showed that tralokinumab had a positive impact on patients’ lives by improving itch, sleep quality, overall quality of life, and mental health (Citation7). Real-life studies on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) during tralokinumab treatment are limited, even though promising real-life data have already been published about itch, sleep quality, and disease control in small samples (Citation8–9).

Our study analyzes PROs trends over 24 weeks in 60 patients with severe AD at two tertiary care centers. Tralokinumab was administered concurrently with systemic corticosteroids in 5 (8.4%) patients and with cyclosporin in 10 (16.7%) patients for the first 4 weeks. The baseline epidemiological and clinical characteristics of our population are summarized in . Clinical monitoring was conducted using the EASI, Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (average itch within the past 24 h) (Citation10), Sleep NRS, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) (Citation11), Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT) (Citation12), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Citation13), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Citation14). These data were collected at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of treatment.

Table 1. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics at baseline.

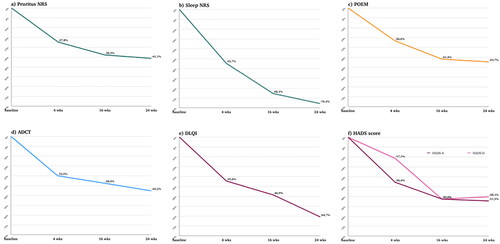

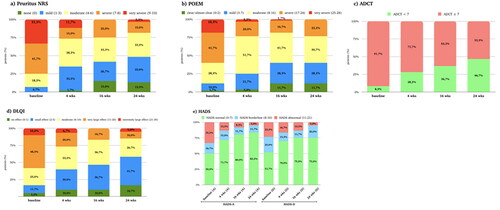

The data were represented using the mean and standard deviation (SD) in the case of a normal distribution, and the median and interquartile range (IQR) in the case of a non-normal/skewed distribution. depicts the percentage improvements in PROs scores, while illustrates the distributions of score classes at different time points.

Figure 1. (a–f) Percentage improvement of pruritus NRS (a), sleep NRS (b), POEM (c), ADCT (d), DLQI (e) and HADS-a/HADS-D (f) from baseline at 4, 16 and 24 weeks of treatment. Wks: weeks; NRS: numerical rating scale; POEM: patient-oriented eczema measure; ADCT: atopic dermatitis control tool; DLQI: dermatological life quality index; HADS-A: hospital anxiety and depression scale (anxiety); HADS-D: hospital anxiety and depression scale (depression).

Figure 2. (a–e) Distribution of the population (expressed in percentage) in the different PROs score categories at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy. (a) Distribution of the population in the different NRS pruritus score classes at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy. Pruritus NRS was classified in five categories: none (0 point), mild (1–3 points), moderate (4–6 points), severe (7–8) and very severe (9–10). (b) Distribution of the population in the different POEM score classes at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy. POEM was classified as following: 0–2 (clear/almost clear), 3–7 (mild), 8–16 (moderate), 17–24 (severe), 25–28 (very severe). (c) Distribution of the population in the different ADCT score classes at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy. ADCT was classified as following: 0–7 (under control) and ≥7 points (not in control); (d) Distribution of the population in the different DLQI score classes at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy DLQI was classified as following: no effect on patient’s life (0–1 points), small effect (2–5 points), moderate effect (6–10 points), very large effect (11–20) and extremely large effect (21–30 points). e) Distribution of the population in the different HADS-a and HADS-D score classes at baseline and after 4, 16 and 24 weeks of therapy. HADS was classified either for anxiety and depression as following: normal (0–7 points), borderline (8–10 points) and abnormal (11–21). Wks: weeks; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: dermatological life quality index; POEM: patient-oriented eczema measure; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; HADS-A: hospital anxiety and depression scale (anxiety); HADS-D: hospital anxiety and depression scale (depression). Wks: weeks; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: dermatological life quality index; POEM: patient-oriented eczema measure; HADS-A: hospital anxiety and depression scale (anxiety); HADS-D: hospital anxiety and depression scale (depression).

Pruritus NRS decreased from an average of 7.4 (2.1) at the study’s outset to 3.9 (2.6) by week 24 (p-value < 0.001), showing progressive improvement over time. The percentage of individuals experiencing severe itching decreased from 33.3% at baseline to 3.3% at week 24, while those with mild or no itching increased from 6.9% to 48.3%. Sleep quality significantly improved, decreasing from a median of 7.0 (2.0–8.0) at baseline to 0.5 (0.0–3.0) at week 24 (p-value < 0.001). POEM scores reduced from an initial average of 17.5 (7.1) to 9.6 (6.3) by week 24 (p-value < 0.001). A shift was observed from initial very severe scores to scores indicating clear, almost clear, or mild symptoms. ADCT scores improved, declining from an initial mean of 15.8 (6.6) to 8.3 (5.7) at week 24 (p-value < 0.001). The percentage of patients with ADCT scores < 7 raised from 8.3% at T0 to 46.7% at week 24. DLQI exhibited marked enhancements, with a reduction from a median of 12.0 (8.0–16.0) at baseline to 4.0 (2.0–7.8) at week 24 (p-value < 0.001). In 24 weeks, patients with a very large or extremely large quality of life impact decreased (48.3–10.0%), and no/low impact increased (5.0–41.7%). Furthermore, anxiety and depression, as measured by HADS, displayed notable reductions. Anxiety scores decreased from a median of 7.5 (5.0–12.8) to 4.0 (1.3–6.8) (p-value < 0.001), while depression scores decreased from 7.0 (4.0–10.0) to 3.5 (1.0–7.8) (p-value < 0.001). Notably, even though only 33.3% and 23.3% had abnormal values for HADS-A and HADS-D, respectively, a reduction in these values was still noted. Consistent with the reduction in the values of PROs, the median EASI score decreased from 24.0 (18.9–24.0) at baseline to 3.0 (1.3–5.0) by week 24 (p-value < 0.001). At the 24-week, 52 out of 60 patients (86.7%) attained an EASI score of ≤7. Additionally, 26 patients (43.3%) achieved a 75% reduction from baseline in EASI (EASI-75), 14 patients (23.3%) achieved EASI-90, and 6 patients (10.0%) reached EASI-100.

In terms of adverse events, there were 2 cases of facial redness, 3 of psoriasis, and 4 of conjunctivitis recorded. All 60 patients completed the 6 months of treatment; however, after this period, we observed a total of 9 cases of discontinuation. Of these, 1 case was due to a desire for pregnancy, 5 were due to inefficacy, and 3 were attributed to the occurrence of psoriasis.

The limitations of our study are the small population of highly treatment-resistant and severely affected patients, as well as the 6-month observation period. This likely accounts for the variance in results when compared to ECZTRA3, which included treatment-naive patients with a mix of moderate and severe AD. In contrast, our population is more like a ‘real-life’ scenario, similar to ECZTRA7 (Citation15), where we achieved overall superior results. Overall, this study demonstrates the clinical and statistical effectiveness of tralokinumab in progressively improving EASI and PROs, with a notable impact on itching, sleep disruptions, anxiety, and depression. Our study’s limitations include the concurrent use of topical corticosteroids or cyclosporin in a subset of patients during tralokinumab therapy, potentially influencing observed outcomes. The small sample size of highly treatment-resistant patients and the six-month observation period limit generalizability. Future research with larger, diverse cohorts and extended follow-up is needed to assess tralokinumab’s standalone effectiveness and long-term sustainability in managing atopic dermatitis.

Acknowledgements

S. Ferrucci and F. Barei, have contributed equally to the conception, realization and writing the paper and both qualify as first author; A.V. Marzano, L. Naldi and E. Pezzolo have revised the manuscript; F. Barei did the statistical analysis. This is a retrospective study, so no ethics committee approval was needed. The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details.

Disclosure statement

S. Ferrucci is principal investigator in clinical trial to Amgen, Sanofi, Novartis, Lilly, Leo Pharma, Abbvie and she is advisory board or speaker to Novartis, Menarini, Sanofi, Abbvie and Leo Pharma. The other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. E.Pezzolo has been consultant and speaker for Sanofi Genzyme, LEO Pharma, Novartis, AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, Galderma, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. L.Naldi has been consultant and speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis and Sanofi Genzyme.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mastorino L, Rosset F, Gelato F, et al. Chronic pruritus in atopic patients treated with dupilumab: real life response and related parameters in 354 patients. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(7):1. PMID: 35890180; PMCID: PMC9318403. doi:10.3390/ph15070883.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–4. Epub 2016 Sep 30. PMID: 27690741. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610020.

- Cork MJ, Eckert L, Simpson EL, et al. Dupilumab improves patient-reported symptoms of atopic dermatitis, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and health-related quality of life in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of pooled data from the randomized trials SOLO 1 and SOLO 2. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31(6):606–614. Epub 2019 Jun 9. PMID: 31179791. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1612836.

- Miniotti M, Ribero S, Mastorino L, et al. Long-term psychological outcome of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis continuously treated with Dupilumab: data up to 3 years. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(6):852–858. Epub 2023 Mar 10. PMID: 36856013. doi:10.1111/exd.14786.

- Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(3):437–449. Epub 2020 Dec 30. PMID: 33000465; PMCID: PMC7986411. doi:10.1111/bjd.19574.

- Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(3):450–463. Epub 2021 Feb 22. PMID: 33000503; PMCID: PMC7986183. doi:10.1111/bjd.19573.

- Simpson EL, Wollenberg A, Soong W, et al. Patient-oriented measures for phase 3 studies of tralokinumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (ECZTRA 1, 2, and 3). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129(5):592–604.e5. Epub 2022 Jul 14. PMID: 35843520. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.07.007.

- Gargiulo L, Ibba L, Vignoli CA, et al. Tralokinumab rapidly improves subjective symptoms and quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a real-life 16-week experience. J Dermatol Treat. 2023;34(1):2216815. PMID: 37246920. doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2216815.

- Pezzolo E, Schena D, Gambardella A, et al. Survival, efficacy and safety of tralokinumab after 32 and 52 weeks of treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults: a multicentre real-world study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37483150. doi:10.1111/jdv.19382.

- Reich A, Heisig M, Phan NQ, et al. Visual analogue scale: evaluation of the instrument for the assessment of pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(5):497–501. PMID: 22102095. doi:10.2340/00015555-1265.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, et al. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores into clinical practice by suggesting severity strata derived using anchor-based methods. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(6):1326–1332. PMID: 24024631; PMCID: PMC3920642.] doi:10.1111/bjd.12590.

- Pariser DM, Simpson EL, Gadkari A, et al. Evaluating patient-perceived control of atopic dermatitis: design, validation, and scoring of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT). Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(3):367–376. Epub 2019 Dec 12. PMID: 31778083. doi:10.1080/03007995.2019.1699516.

- Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, et al. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659–664. PMID: 16185263. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. PMID: 6880820. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

- Gutermuth J, Pink AE, Worm M, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids in adults with severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to or intolerance of ciclosporin A: a placebo-controlled, randomized, phase III clinical trial (ECZTRA 7). Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(3):440–452. doi:10.1111/bjd.20832.