Abstract

Background

Systematic reviews (SRs) could offer the best evidence supporting interventions, but methodological flaws limit their trustworthiness in decision-making. This cross-sectional study appraised the methodological quality of SRs on atopic dermatitis (AD) treatments.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Database for SRs on AD treatments published in 2019–2022. We extracted SRs’ bibliographical data and appraised SRs’ methodological quality with AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) 2. We explored associations between methodological quality and bibliographical characteristics.

Results

Among the 52 appraised SRs, only one (1.9%) had high methodological quality, while 45 (86.5%) critically low. For critical domains, only five (9.6%) employed comprehensive search strategy, seven (13.5%) provided list of excluded studies, 17 (32.7%) considered risk of bias in primary studies, 21 (40.4%) contained registered protocol, and 24 (46.2%) investigated publication bias. Cochrane reviews, SR updates, SRs with European corresponding authors, and SRs funded by European institutions had better overall quality. Impact factor and author number positively associated with overall quality.

Conclusions

Methodological quality of SRs on AD treatments is unsatisfactory. Future reviewers should improve the above critical methodological aspects. Resources should be devolved into upscaling evidence synthesis infrastructure and improving critical appraisal skills of evidence users.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a prevalent form of eczema characterized by chronic skin inflammation resulting in symptoms such as dryness, itchiness, and skin cracking (Citation1,Citation2). Its pathogenesis has not yet completely understood but is believed to involve the contributions of genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors (Citation2). It has been estimated that AD affects up to 20% of children and 10% of adults worldwide (Citation1). Most children start developing AD symptoms as early as three to six months (Citation2). AD is associated with other medical conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergies, depression, and suicidal ideation (Citation3,Citation4). A variety of topical and systemic treatments, as well as phototherapy, are available to help reduce pruritus and establish persistent disease control, aiming to improve patients’ quality of life and functionality (Citation3,Citation4). Topical anti-inflammatory agents and moisturizers are the mainstay of routine AD management, and in managing more severe cases, are often used in conjunction with oral medications like immunosuppressants (Citation3,Citation4). The estimated yearly cost per AD patient in the United States ranged from USD108 to USD4,831 based on severity, and the total healthcare spending of the country for AD has been estimated to be USD5 billion each year (Citation5).

Facing the rapid development in dermatology, healthcare professionals must rely on the best, most up-to-date clinical guidelines to help their selection of interventions in routine practice. These clinical guidelines are usually supported by findings from systematic reviews (SRs). Well-conducted SRs provide high-quality evidence by synthesizing empirical research that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer specific research questions (Citation6). When appropriate, meta-analyses may be performed on top of SRs to provide further quantitative evidence (Citation6). However, concerns have been raised regarding the limitations and flaws in SR methodology in recent years (Citation7,Citation8), of which those limitations and flaws may lead to overestimation or underestimation of treatment benefits and harms (Citation7), resulting in improper clinical decisions and suboptimal patient care.

Considering the importance of clarifying the trustworthiness of clinical evidence, we conducted a cross-sectional study to appraise the methodological rigor of a recent representative sample of SRs on AD treatments using AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) 2 and investigate the potential bibliographical predictors of methodological quality.

Methods

The methodology of this study was based on recently published cross-sectional studies of SR methodological quality in other areas (Citation9–14).

Eligibility criteria

We included SRs published between January 2019 and September 2022 in English or Chinese, with at least one meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials on AD treatments. We imposed no restrictions on the type of interventions (i.e., pharmacological or non-pharmacological) evaluated. We excluded narrative reviews, protocols, overviews of SRs, and network meta-analyses. In cases of duplicate SRs, we considered only the most recent publications.

Literature search and selection

We performed a comprehensive literature search in four databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, from January 2019 to September 2022 to identify a representative sample of relevant SRs on AD treatments. We employed validated filters for RCTs and SRs to balance specificity and sensitivity when searching MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO (Citation15–17). Supplementary Table S1 presents the details of the search strategies.

We imported retrieved citations into EndNote. After removing duplicates, two authors independently examined the titles and abstracts and then evaluated the full text of potential studies to determine their eligibility for inclusion. The two authors discussed to reconcile differing opinions. Discrepancies were referred to a senior author for final decisions.

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

We extracted the bibliographical characteristics of included SRs with an 18-item pre-designed form. This data extraction form has been used in previous SR appraisals (Citation9–14), and the items were shown to have potential associations with SR methodological quality. Supplementary Table S2 contains information about the questionnaire.

We used the validated AMSTAR 2 assessment tool to evaluate the methodological quality of included SRs (Citation18). AMSTAR 2 is an instrument with 16 items for critically appraising SRs, of which seven are critical to methodological quality according to the guidance document (Citation18):

(Item 2) Publishing and registering a priori protocol outlining before initiating the review and justifying any protocol deviations.

(Item 4) Performing a comprehensive literature search.

(Item 7) Providing a list of excluded studies with justifications.

(Item 9) Using appropriate tools to assess the risk of bias in the included SRs.

(Item 11) Employing appropriate meta-analysis methods.

(Item 13) Considering the risk of bias in individual studies when interpreting SR results.

(Item 15) Conducting adequate investigation of publication bias and discussing its likely impact on the results.

Each SR was rated high, moderate, low, or critical low according to its performance across the domains. Supplementary Table S3 outlines the AMSTAR 2 domains items and the methods to determine the overall methodological quality of the SR. Two authors independently performed data extraction and quality assessment. In case of any disagreements, the authors reached a consensus through discussion. If the disagreement persisted, it was arbitrated by a senior author.

Data analysis

We summarized bibliographic characteristics, AMSTAR 2 domain assessment results, and overall methodological quality of SRs using descriptive statistics, including percentages, frequencies, ranges, and medians. We analyzed the differences in overall methodological quality of SRs across bibliographical characteristics with Kruskal-Wallis tests or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

Results

Literature search and selection

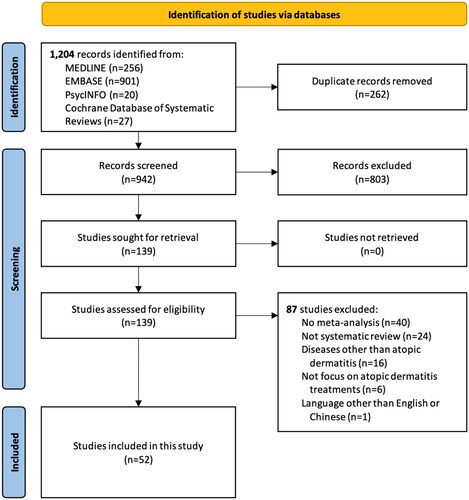

We retrieved 1,204 records through the literature search and assessed 139 full-text articles after removing duplicates and examining titles and abstracts. Finally, a total of 52 SRs met the eligibility criteria and were included in this cross-sectional study. shows the details of the selection process.

Bibliographical characteristics of systematic reviews on atopic dermatitis treatments

presents the bibliographical characteristics of the 52 SRs containing 973 RCTs with 516,830 participants. Among the included SRs, 11.5% (n = 6) were Cochrane reviews, and 13.4% (n = 7) were updates of previous SRs. The journal impact factors of the SRs ranged from 0 to 14.71, with a median of 4.35. The number of review authors ranged from 2 to 26, with a median of 5. Thirty-one (59.6%) corresponding authors were from Asia, 12 (23.1%) from Europe, seven (13.5%) from America, one (1.9%) from Oceania, and one (1.9%) from Africa. Most SRs (n = 42; 80.8%) evaluated the pharmacological interventions for AD, and seven (13.5%) focused on non-pharmacological interventions.

Table 1. Bibliographical characteristics of the 52 included systematic reviews on atopic dermatitis treatments.

Nearly half (n = 24; 46.2%) of the included SRs did not report on funding sources, while the remaining received funding primarily from institutions or organizations in Asia (n = 13; 25.0%) or Europe (n = 10; 19.2%). As many as 71.2% (n = 37) of SRs reported information on intervention harms. Most (n = 49; 94.2%) SRs included a PRISMA (the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis)-like flow diagram. SR authors tended to use the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess the risk of bias (n = 37; 71.2%), and only one SR (1.9%) used the Jadad scale. All SRs authors conducted literature searches in English databases, yet only 34.6% (n = 18) of SRs involved searching non-English databases. Thirty (57.7%) SRs included primary studies published in English and other languages, and 22 (42.3%) included English publications only. Most SRs reported the year of literature coverage (n = 51; 98.0%). Half and around half of the included SR used topics, free text, keywords, or Medical Subject Headings as search terms (n = 26; 50.0%) and full Boolean (n = 24; 46.2%), respectively.

Methodological quality of systematic reviews

Performance across individual AMSTAR 2 domains

and Supplementary Table S4 illustrates the performance of the included SRs across each AMSTAR 2 domain item. The appraised SRs had poor performance across most of the non-critical domains, of which only four domain-specific items were satisfied by more than 70.0% SRs: all included the components of PICO (population, intervention, comparators, and outcomes) in their research questions and inclusion criteria, 42 (80.8%) had their authors performing data extraction in duplicate (item 6), 40 (76.9%) reported potential sources of conflict of interest, including the funding received for conducting the review (item 16), and 39 (75.0%) had their authors performing study selection in duplicate (item 5).

Table 2. Results of the AMSTAR2 domain items for the 52 included systematic reviews on atopic dermatitis treatments.

Their performance across the AMSTAR 2 critical domains was also unsatisfactory. Only two domain-specific items were fulfilled by at least 70.0% of SRs: 45 (86.5%) used appropriate techniques for evaluating the risk of bias in included primary studies (item 9) and 41 (78.8%) used appropriate methods for statistical combination of results (item 11). Unfortunately, only 24 (46.2%) performed an adequate investigation of publication bias and discussed its likely impact on the results (item 15), 21 (40.4%) contained an explicit statement that the review methods were established before reviewing and justified significant deviations from the protocol (item 2), 17 (32.7%) considered the risk of bias in primary studies when interpreting or discussing the results (item 13), seven (13.5%) provided a list of excluded studies and justified the exclusions (item 7), and five (9.6%) employed a comprehensive literature search strategy (item 4).

Overall methodological quality

shows the overall methodological quality of the included SRs and the details of the Kruskal-Wallis tests. Of the 52 appraised SRs, only one (1.9%) was of high overall methodological quality, and six (11.5%) were of low quality. None were of moderate methodological quality, while the remaining 45 (86.5%) SRs were of critically low quality. We identified significant between-group differences in four bibliographical characteristics from the Kruskal-Wallis tests. Specifically, Cochrane reviews (p = 0.004), updates of previous SRs (p = 0.027), SRs with the corresponding author from Europe (p = 0.007), and SRs funded by institutions or organizations in Europe (p = 0.002) were associated with better overall methodological quality, compared to their counterparts. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients also revealed that journal impact factor (rs=0.44; p = 0.001) and number of authors (rs=0.47; p < 0.001) had positive associations with overall methodological quality.

Table 3. Overall methodological quality of the 52 included systematic reviews on atopic dermatitis treatments by bibliographical characteristics.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This cross-sectional study critically appraised 52 SRs on AD treatments published between January 2019 and September 2022. Only one (1.9%) was of high overall quality, six (11.5%) of low quality, and the remaining 45 (86.5%) of critically low quality. Less than half of the SRs fulfilled the AMSTAR 2 critical domains of performing an adequate investigation of publication bias and discussed its likely impact on the results, containing an explicit statement that the review methods were established before reviewing and justified significant protocol deviations, considering the risk of bias in primary studies when interpreting or discussing the results, providing a list of excluded studies and justified the exclusion, or employing a comprehensive literature search strategy. Cochrane reviews, updates of SRs, SRs with the European corresponding author, SRs funded by European funders, journal impact factor, and number of authors showed a positive relationship with overall methodological quality.

Agreements and disagreements with similar studies

The proportion of SRs on AD treatments having high overall quality (1.9%) is comparable to those on septic treatments (2.0%) (Citation14), osteoporotic treatments (1.0%) (Citation11), acupuncture effectiveness (0.9%) (Citation10), and Chinese herbal medicine effectiveness (0.7%) (Citation12). However, they are significantly lower than those on asthma treatments (8.8%) (Citation13) and Alzheimer’s disease treatments (3.9%) (Citation9). For AMSTAR 2 critical domains, SRs on AD treatments performed worse than those on septic treatments in terms of providing a list of excluded studies with justifications (item 7) (13.5% versus 21.6%) and those on Chinese herbal medicine effectiveness, acupuncture effectiveness, and osteoporotic treatments in terms of accounting for the risk of bias in individual studies when interpreting SR results (item 13) (32.7% versus 78.4% versus 73.6% versus 62.4%). SRs on AD treatments also performed worse than the SRs on septic treatments, osteoporotic treatments, and Chinese herbal medicine effectiveness in conducting sufficient investigations of publication bias (46.2% versus 76.5% versus 64.4% versus 60.1%) (item 15).

Implications for research

Considering the unsatisfactory performance of the recent SRs on AD treatments across the AMSTAR 2 critical domains, we will discuss several recommendations for future systematic reviewers in this particular field in the paragraphs below.

First and foremost, less than half of the included SRs stated explicitly the availability of a priori review protocols. This is concerning because, without such protocols, SR readers are likely to be prevented from comparing the review methodology and results presented in the publications to the original, planned approaches, providing reasonable grounds for them to suspect selective outcome reporting in the SRs and influencing evidence uptake (Citation19). The absence of review protocols may also give rise to research waste given that systematic reviewers are unable to know whether there are other SRs on similar topics and approaches (Citation20,Citation21). Therefore, we recommend systematic reviewers publish or register their protocols in peer-reviewed journals or international databases, such as PROSPERO, respectively (Citation22), and state clearly the administrative information (e.g., title, authors, and funding sources), introduction (e.g., rationale and objectives), and methods (e.g., search strategy, information sources, eligibility criteria, outcomes, risk of bias assessment approach, and data management procedures) of the proposed review (Citation20).

As less as only one-tenth of the included SRs on AD treatments fulfilled the criteria for the successful execution of a comprehensive literature search. Failing to conduct an adequate search may result in an incomplete and biased selection of studies, potentially compromising the reliability and validity of the findings and leading to erroneous conclusions and recommendations (Citation6). So, it is advisable for systematic reviewers to follow the requirements listed in the AMSTAR 2 domain to ensure the trustworthiness of their works. Specifically, they should aim to search in a minimum of two databases for potential studies, provide all utilized keywords in search strategies, and justify any publication restrictions (e.g., publication date of primary studies). To further enhance search comprehensiveness, systematic reviewers should perform a meticulous check of reference lists, explore grey literature and other unpublished sources, seek input from field experts and review methodologists, and update the literature search if they are unable to complete the review within 24 months (Citation6). As excluding non-English studies introduces language bias and may therefore influence the direction and magnitude of results (Citation23), we also recommend SR teams include members with diverse language and cultural backgrounds or external translators (or translation systems driven by artificial intelligence) who can have constant involvement in the review process (Citation24,Citation25).

Besides the list of included primary studies, it is paramount to provide the list of excluded primary studies and the rationale behind the exclusions. It is because doing so may minimize the subjective nature of literature selection, promote transparency and reproducibility in the review process (Citation26), and, most importantly, help reduce the risk of exclusion errors (Citation6,Citation18). Unfortunately, only 13.5% of the included SRs on AD treatments acknowledged and adopted such practices. Future systematic reviewers in the field should endeavor to provide a list of excluded studies with rationale, not only to serve the mentioned advantages but also to assist readers in accessing primary studies that, while ineligible for inclusion in the SRs, may still hold relevance to the field and aid in identifying gaps in the literature, informing directions for future research (Citation6,Citation27).

Risk of bias refers to the potential for systematic errors in a study’s design, conduct, or analysis that can influence its results (Citation10,Citation28). If an SR fails to assess the risk of bias in the primary studies included, it may draw conclusions unsupported by the available evidence and fail to identify limitations in the evidence, giving rise to overestimated or underestimated SR results and subsequently leading to inappropriate clinical or policy decisions and futile interventions or serious consequences (Citation18,Citation29). Despite the potential impacts, only about one-third of the included SRs on AD treatments accounted for the risk of bias in all the primary studies when interpreting and discussing their results. Similarly, publication bias is a potential concern in evidence synthesis for AD treatments. It refers to the failure to publish the results of a study based on the direction or strength of the findings (Citation30). Evidence has suggested that studies with positive or statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) results tend to be accepted and published (Citation28,Citation31) or take a shorter time to go through the procedures required for publication (Citation32,Citation33). In other words, ignoring publication bias may cause an overestimation of treatment effects and incorrect conclusions and recommendations (Citation34). However, less than half of the included SRs on AD treatments performed graphical or statistical tests for publication bias and discussed its likelihood and magnitude of impact. Hence, last but not least, to safeguard the robustness of future SRs on AD treatments, systematic reviewers are recommended to refer to all possible effects brought by the risk of bias when interpreting and discussing the results of their reviews and spot potential publication bias among primary studies using various methods, such as funnel plot asymmetry tests and Egger’s regression tests (Citation18,Citation35). They should also discuss the likelihood and magnitude of the impact of publication bias.

Implications for practice

Our results illustrated that most recent SRs on AD treatments had critically low methodological quality. They echo the findings presented in a recent critical appraisal of the published AD clinical guidelines that there is a potential shortage in terms of methodological expertise for evidence synthesis in this research and clinical area (Citation36). In light of that, medical authorities, research institutes, and universities should have the visions and missions to upscale the infrastructure of evidence-based medicine education and continuous training and devolve resources into improving the knowledge and skills of clinicians and researchers in conducting robust systematic reviews and developing reliable clinical guidelines. While awaiting future enhancement in review and guideline methodological quality, we recommend evidence users critically appraise the methodological rigor of SRs, using validated tools (e.g., AMSTAR 2), before applying the findings in clinical and policy decision-making. In particular, they should pay attention to the concerns revealed by this cross-sectional study, including the evaluation of publication bias impact, the availability of a priori protocols and justifications for protocol deviations, the consideration of risk of bias in primary studies, the provision of excluded study lists and rationale for exclusion, and the comprehensiveness of literature search strategy. Doing so may reduce the chance of having overestimated or underestimated research findings to jeopardize the reliability and validity of decisions. Moreover, as gatekeepers, journal editors have the responsibility to apply validated critical appraisal tools to assess the quality of submitted SRs, not only for the sake of journal reputation but also for the trustworthiness of evidence in the field in general (Citation37).

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, we included only studies published in English and Chinese and searched only representative English databases. Such restrictions might result in overlooking significant publications in other languages and giving rise to language bias. Second, we did not include and appraise network meta-analysis of AD treatments due to the constraint of AMSTAR 2. Lacking relevant evidence might fail to create a complete picture of the knowledge landscape. Third, we were only able to conduct critical appraisals based on the information provided by the publications. Therefore, the accuracy of methodological assessment of SRs with poor reporting quality or published in journals with stringent word limits might be influenced.

Conclusions

The methodological quality of SRs on AD treatments was far from satisfactory. Future reviewers should pay attention to performing an adequate investigation of publication bias and discussing its likely impact on the results, publishing or registering an a priori protocol and justifying protocol deviations, considering the risk of bias in primary studies when interpreting or discussing the results, providing a list of excluded studies with justifications, and employing a comprehensive literature search strategy. Evidence users should carry out critical appraisal before accepting the results for clinical and policy decision-making.

Author contributions

LH: Collection and assembly of data; Data analysis and interpretation; Manuscript writing. YMKC: Collection and assembly of data; Data analysis and interpretation; Manuscript writing. CCCC: Data analysis and interpretation; Manuscript writing. IXYW: Conception and design. CM: Conception and design. VCHC: Conception and design; Manuscript writing; Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (381.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- DynaMed. Atopic dermatitis ipswich., United States: EBSCO Information Services; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.dynamed.com/condition/atopic-dermatitis.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.002.

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London, (UK): The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020 [cited 2023 Jun 22]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Ioannidis JP. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485–514. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12210.

- Johnston A, Kelly SE, Hsieh SC, et al. Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: a methodological guide. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;108:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.030.

- Zhong CCW, Zhao J, Wong CHL, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews on treatments for Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):159.

- Ho L, Ke FYT, Wong CHL, et al. Low methodological quality of systematic reviews on acupuncture: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01437-0.

- Tsoi AKN, Ho L, Wu IXY, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews on treatments for osteoporosis: a cross-sectional study. Bone. 2020;139:115541. Octdoi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115541.

- Cheung AKL, Wong CHL, Ho L, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews on chinese herbal medicine: a methodological survey. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12906-022-03529-w.

- Wu IXY, Deng Y, Wang H, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analysis on asthma treatments. A cross-sectional study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(8):949–957. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-187OC.

- Ho L, Chen X, Kwok YL, et al. Methodological quality of systematic reviews on sepsis treatments: a cross-sectional study. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;77:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.12.001.

- McMaster Health Information Research Unit. Search Strategies for PsycINFO in Ovid Syntax. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster Health Information Research Unit; 2023 [cited 2023 Jun 20]. Available from: https://hiruweb.mcmaster.ca/hkr/hedges/psycinfo/.

- McMaster Health Information Research Unit. Search Strategies for EMBASE in Ovid Syntax. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster Health Information Research Unit; 2023 [cited 2023 Jun 20]. Available from: https://hiruweb.mcmaster.ca/hkr/hedges/embase/.

- McMaster Health Information Research Unit. Search Filters for MEDLINE in Ovid Syntax and the PubMed translation. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster Health Information Research Unit; 2023 [cited 2023 Jun 20]. Available from: https://hiruweb.mcmaster.ca/hkr/hedges/medline/.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008.

- Kirkham JJ, Altman DG, Williamson PR. Bias due to changes in specified outcomes during the systematic review process. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9810–e9810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009810.[PMC] [20339557

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- The PLoS Medicine Editors. Best practice in systematic reviews: the importance of protocols and registration. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1001009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001009.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination – University of York. About PROSPERO. York, United Kingdom: centre for Reviews and Dissemination – University of York; 2020 [cited 2023 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage.

- Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, et al. The effect of english-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–144. doi: 10.1017/S0266462312000086.

- Walpole SC. Including papers in languages other than English in systematic reviews: important, feasible, yet often omitted. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.004.

- Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, et al. The accuracy of google translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):677–679. doi: 10.7326/M19-0891.

- Faggion CM. Critical appraisal of AMSTAR: challenges, limitations, and potential solutions from the perspective of an assessor. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0062-6.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias – an updated review. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e66844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066844.[PMC] [23861749

- Almeida MO, Yamato TP, Parreira P, et al. Overall confidence in the results of systematic reviews on exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: a cross-sectional analysis using the assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 tool. Braz J Phys Ther. 2020;24(2):103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.04.004.

- Dickersin K, Min YI. Publication bias: the problem that won’t go away. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;703(1):135–148. discussion 146-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26343.x.

- Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081.

- Ioannidis JP. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. JAMA. 1998;279(4):281–286. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.281.

- Hopewell S, Clarke M, Stewart L, et al. Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(2):Mr000011.

- van Assen MA, van Aert RC, Wicherts JM. Meta-analysis using effect size distributions of only statistically significant studies. Psychol Methods. 2015;20(3):293–309. doi: 10.1037/met0000025.

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

- Arents BWM, van Zuuren EJ, Vermeulen S, et al. Global Guidelines in Dermatology Mapping Project (GUIDEMAP), a systematic review of atopic dermatitis clinical practice guidelines: are they clear, unbiased, trustworthy and evidence based (CUTE)? Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(5):792–802. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20972.

- Mittal N, Goyal M, Mittal PK. Understanding and appraising systematic reviews and meta-analysis. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;41(5):317–326. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-41.5.317.