ABSTRACT

According to international law, prisoners should have access to healthcare on an equivalent basis to the rest of the population, and the UK Government has stated its commitment to such equivalence. Healthcare provision in English prisons has seen several reorganisations, notably in 2006 and 2013, with the stated intentions of improving healthcare provision in prisons. This article focuses on prisoners’ reported experiences over the periods of changes in healthcare governance, with the aim of identifying whether there are improvements from their perspectives. Survey data from a sample of prisoners has been collected by HM Inspectorate of Prisons for over 20 years, and these data have been used for secondary analysis of prisoners’ health needs and experiences of healthcare in English prisons. Despite the reorganisations of healthcare governance, the trends from 2003 to 2019 are of increasing health needs of prisoners and decreasing initial access, ongoing access, and quality of healthcare provision. There is little indication of any improvements experienced by prisoners from the 2006 or 2013 reorganisations. Prisoners are widely recognised as having distinct healthcare needs, but the data analysis reveals demographic differences in health needs and health access within the prison population, and an overall decline in quality and accessibility of healthcare provision in English prisons.

Introduction

According to international law, prisoners should have access to healthcare on an equivalent basis to the rest of the population. The principle of equivalence was introduced by the United Nations in 1982 via Resolution 37/194 and enshrined in international law in Principle 9 of the UN Basic Principles of Treatment of Prisoners (Ismail & de Viggiani, Citation2018b). The state’s duty of care to protect prisoners’ right to health is further strengthened in Europe via Articles 3 and 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, making clear that this is a rights-based framing underpinning healthcare provision in prison. Till et al. (Citation2014, p. 181) emphasise that equivalence is a ‘minimally acceptable standard, rather than an ideal one’, and highlight that prisoners may have additional healthcare needs and that providing healthcare within the criminal justice system may pose additional challenges. Numerous studies have considered prisoners’ particular healthcare needs, for example Glorney et al. (Citation2018) highlighting traumatic brain injury (TBI), and women in prison having a higher frequency of repeated TBIs than men. Harris et al. (Citation2006) provide a systematic overview from primary care nursing in prisons in England and Wales and highlight significantly greater degrees of mental health problems, substance abuse, and worse physical health in prisoners than in the general population. They also conclude that women, young offenders, older prisoners, and prisoners from minority ethnic groups have distinct health needs compared to the prison population taken as a whole, which has implications for the provision of prison healthcare, and how these needs are met.

Brief history of healthcare governance in English prisons

Despite the 1982 UN declaration of prisoners’ right to equivalence, Reed and Lyne (Citation1997, p. 1423) concluded that in England and Wales ‘for many prisoners this right is not met’. They outlined a history from a Home Office working party in 1962 which was ‘set up to consider how the prison medical service was organised and how relations with the NHS could be improved’ and that all major healthcare bodies, except the British Medical Association (BMA) advised that the prison medical service should be integrated with the NHS. As a result, the recommendation was of no change to the prison medical service, as was concluded again in 1979 (Reed & Lyne, Citation1997, p. 1423). An ‘efficiency scrutiny’ of the prison medical service in 1990 recommended a purchaser-provider split in prison healthcare with the assumption that most healthcare would be contracted-in from the NHS and therefore of equivalent quality. However, Reed and Lyne (Citation1997) concluded that the Health Care Service for Prisoners remained a small, isolated service of variable quality, with uncertain lines of responsibility and accountability due to individual prisons being responsible for purchasing healthcare. Their review of 19 prisons in England and Wales for HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) overwhelmingly favoured the integration of the NHS and the Health Care Service for Prisoners.

The concept of healthcare equivalence in English prisons was therefore first clearly introduced in 1999 in a working group report on the future organisation of prison healthcare provision by the Joint Prison Service and National Health Service Executive (Ismail & de Viggiani, Citation2018b; Sim, Citation2002). International reviews of healthcare in prisons find similarly slow or patchy progress towards equivalence in prison healthcare, including lack of evidence on governance models (McLeod et al., Citation2020); and Niveau (Citation2007) highlights the UK as a more positive example of adopting the principles and putting them into practice. Ismail and de Viggiani (Citation2018b, p. 746) emphasise that the principle should mean that prisoners receive equivalence of healthcare before, during and after detention and report that ‘Academics, policy-makers and practitioners widely approved of the change in policy’.

The UK Government continues to affirm its commitment to equivalence of healthcare in prisons (HM Government, Citation2019), stating that:

The co-chairs of the National Prison Healthcare Board affirm that: ‘Equivalence’ is the principle which informs the decisions of the National Prison Healthcare Board so that member agencies’ statutory and strategic objectives and responsibilities to arrange services are met, with the aim of ensuring that people detained in prisons in England are afforded provision of and access to appropriate services or treatment (based on assessed population need and in line with current national or evidence-based guidelines) and that this is considered to be at least consistent in range and quality (availability, accessibility and acceptability) with that available to the wider community, in order to achieve equitable health outcomes and to reduce health inequalities between people in prison and in the wider community.

The 2006 reorganisation: ending the separate prison medical service

The practicalities of healthcare provision in prisons have been through further reorganisations since initial recommendation of Department of Health takeover of responsibility following the 1996 report ‘Patient or Prisoner?’ (Home Office, Citation1996), as well as there being differences in prison provision in England and Wales from the rest of the UK, and the more recent differences of NHS management between England and Wales. Cornford et al. (Citation2007, p. 1202) characterise the 2006 reorganisation, which ended the Prison Medical Service in England and Wales, as aiming to improve the quality of care in prisons and claim that ‘by April 2006 all prison health services should be commissioned by Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) under the overall management of Strategic Health Authorities’. Following this reorganisation, Cornford et al. (Citation2008) carried out an audit of prison healthcare provision on behalf of the Department of Health receiving survey responses from 122 out of 138 prisons in England and Wales. They found that a wider range of healthcare was provided in higher security prisons than in lower security prisons and that there were ongoing problems with IT and that more than half the prisons had problems retaining nursing staff. They highlighted that the 2006 reorganisation aimed to ‘normalise care in prisons’ so that ‘patients within prisons should receive the equivalent level of care available outside’ (Cornford et al., Citation2008, p. 126).

Further studies have attempted to assess the quality of healthcare in prisons, and whether the transition to an NHS-led primary healthcare service is achieving the intentions of improving quality and equivalence to the healthcare provision to the wider population (Ismail & de Viggiani, Citation2018b; Till et al., Citation2014). Powell et al. (Citation2010) used ethnographic methods to interview healthcare staff in 12 prisons in England in 2005 and reported that the staff identified positive changes, with nurses becoming the key providers of healthcare. However, healthcare staff still acknowledged conflicts between the custody regime and healthcare delivery and that nurses had a gate-keeping role to protect General Practitioners (GPs) from excessive prisoner demands. Ginn (Citation2012, p. 28) reviewed the 2006 changes six years on, concluding that they remained ‘a work in progress’. He identifies as positives the fact that all prison doctors are now qualified GPs and less isolated as they often combine practice in prisons with work in the community and that there is greater equivalence with the NHS ‘norms and expectations’ (Ginn, Citation2012, p. 28). Ten years on, Leaman et al. (Citation2017, p. 139) conclude that ‘English prison healthcare has undergone ‘transformation’ during this period, leading to increased quality of care through organisational engagement, professionalisation of the healthcare workforce, transparency, use of evidence-based guidance and responsiveness of services’. However, they do also highlight the ongoing challenges of limited resources.

Context of prison funding and prison population

The context of healthcare in prison is one of the limited funding, with a significant fall in prison funding since 2010 (HMIP, Citation2014; Hutchings & Davies, Citation2021b). The prison population grew significantly from 44,246 in 1993 to 82,384 in December 2018 (House of Commons Justice Committee, Citation2019; MOJ, Citation2020b). In addition, many prisoners have mental health problems, the average age of prisoners is rising, and a higher proportion are in prison for serious violent or sexual offences (House of Commons Justice Committee, Citation2019). Hutchings and Davies (Citation2021a) highlight that more recent increases in funding since 2016 have focused on prison safety and staff numbers, rather than on access to or quality of healthcare. A Healthy Prisons Agenda (de Viggiani, Citation2006, Citation2007; Ismail & de Viggiani, Citation2018a) has been an aspiration since the 1990s (HMIP, Citation2021a, Citation2021b), and would cover wider health and wellbeing promotion in addition to healthcare provision, as discussed by Woodall and Freeman (Woodall, Citation2016; Woodall & Freeman, Citation2020). However, Ismail (Citation2019, Citation2020) identifies that austerity policies have impeded this aspiration, and, in terms of the narrower consideration of healthcare provision, have compromised ‘implementation of equivalence in English prisons’ (Ismail & de Viggiani, Citation2018b, p. 746). Piper et al. (Citation2019, p. 579) identify a ‘low point in service delivery’ with deterioration since 2010 following initial improvements since the 2006 reorganisation.

The 2013 reorganisation: transfer to NHS England

In a further reorganisation, following the Health and Social Care Act 2012, responsibility for direct commissioning of healthcare services in prisons in England transferred to NHS England in April 2013, including primary, hospital, drug and alcohol, mental health and dentistry services (HMPPS, Citation2014). NHS England is expected to work closely with other government departments and arms-length bodies, including Public Health England and Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), with responsibilities outlined in the National Partnership Agreement for Prison Healthcare in England (HM Government & NHS England, Citation2018). The objectives of the Partnership include ‘To improve the health and wellbeing of people in prison and reduce health inequalities’ (HM Government & NHS England, Citation2018, p. 6) and the Ministry of Justice continues to have a research priority on health and wellbeing which asks, ‘What factors contribute to an effective within-prison health service and how can we respond to changing demographics and needs?’ (MOJ, Citation2020a, p. 16). The factor considered in this article is the impact on prisoners’ experience of healthcare in prison of high-level policy, management, and commissioning reorganisations.

The current context of healthcare in prisons in England

In November 2018, the Health and Social Care Committee published the report of its inquiry into prison healthcare (House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, Citation2018, p. 3) concluding that ‘The Government is failing in its duty of care towards people detained in England’s prisons’ and that staffing shortages contribute to restricted prisoner access to health and care services. The Government response (DHSC, Citation2019, p. 47) acknowledged the ‘many challenges’ in ‘delivering health and social care in the prison context’ and that ‘healthcare services in the prison estate have a window of opportunity to positively impact the long-term health and care outcomes of prisoners’. The overall historical picture is one of a shift in the commissioning, management, and therefore provision of prison healthcare since the 1990s, with particular reorganisations in terms of England in 2006 and 2013, in part driven by the aspiration of prisoners receiving equivalence of healthcare to the rest of the population. However, it is important also to note that prisoners’ healthcare needs may be distinctive, diverse, and complex (de Viggiani et al., Citation2005). Bradshaw et al. (Citation2017) highlight that adults in contact with the criminal justice system have higher rates of mental and physical health problems, as is the case internationally (Niveau, Citation2007). In addition, Niveau (Citation2007, p. 611) emphasises that the prison setting affects the delivery of healthcare, requiring a proactive initial check-up of every prisoner, whilst managing higher levels of ongoing demand; claiming that UK prisoners consult, on average, three times more often than a demographically equivalent population in the community. Piper et al. (Citation2019) highlight referral delays to healthcare staff and specialists, and the role of prison officers as gatekeepers to accessing healthcare, including staff shortages affecting prisoner escorts, which could have contributed to health deterioration and deaths of prisoners. They also emphasise the importance of well-trained health staff, for the benefit of both staff and prisoners, with prison work providing effective continuing professional development for healthcare workers. In their comprehensive recent overviews of healthcare in prisons in England, Davies et al. (Citation2020, Citation2021; Hutchings & Davies, Citation2021a, Citation2021b) raise key issues of health assessments, access to healthcare in prisons in England, and the quality of healthcare provision when it is accessed. Healthcare standards in prison include recommendations, as in the rest of the NHS, by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2016, Citation2017), and Bradshaw et al. (Citation2017, pp. 1–3) summarise key standards such as a healthcare assessment ‘before the person is allocated to a cell’, and a second stage health assessment within a further seven days.

The evidence gap of prisoners’ perspectives on healthcare provision

The literature discussed above, and in more detail by Hutchings and Davies (Citation2021b), includes surveys of healthcare staff, hospital records, reviews of policy documents, as well as qualitative work in a number of prisons, but there has been limited research on prisoners’ perspectives on healthcare provision. Condon et al. (Citation2007) interviewed 111 prisoners in 12 prisons and found that healthcare was often better in training prisons, rather than local prisons and that there were barriers in open prisons caused by the bureaucracy to access healthcare when prisoners were occupied during working hours. They emphasise the lack of autonomy for prisoners to ensure their healthcare needs are addressed, which continues to be found in more recent research on hospital access (Davies et al., Citation2020) and on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Wainwright et al., Citation2023). Studies elsewhere are similarly small scale in their sample of prisoners’ experiences, for example Rogalska et al. (Citation2022) in Poland and Zaitzow and Willis (Citation2021) in the USA.

This article aims to address the gap in evidence of prisoners’ self-reported experiences of healthcare by using newly-available administrative datasets of prisoner surveys (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Citation2023; HMIP, Citation2023a) which will be discussed further in the next section. The subsequent section will present analysis of these survey data to explore aspects of prisoner demographics and health needs, and prisoners’ experiences of access to healthcare information, initial health assessment, and the quality and accessibility of healthcare professionals during their time in prisons in England. Trends over time and comparisons between different prison types will be discussed with a focus on the prison healthcare reorganisations in 2006 and 2013. The article will conclude with consideration of whether these reorganisations appear to impact prisoners’ experiences of healthcare in prison.

Methods – secondary analysis of prisoner survey data

For over 20 years, HM Inspectorate of Prisons has systematically collected survey data from prisoners as part of their inspections of all prisons in England and Wales (HMIP, Citation2023a, Citation2023b), which are used in reports of each prison, and in the HMIP annual reports. These data on adult prisoners are now being made available for secondary analysis having been prepared during an ESRC-funded project (RHUL, Citation2023) and archived with the UK Data Service (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Citation2023).

Ethical statement

Secondary analysis of these publicly available data, such as that presented in this article, does not require further ethical approval, as this was addressed when the surveys were originally carried out.

Consent to participate

Similarly, consent to participate was addressed by HMIP when they originally carried out the surveys that generated these data that are now publicly available under licence. In addition, recent articles highlight the potential of the scope and detail in these survey data (Quinn et al., Citation2022) and that prisoners were in favour of HMIP survey data being used, including ‘being shared with organizations that would pursue the best interests of prisoners’ (Quinn et al., Citation2020, p. 175).

Data sample

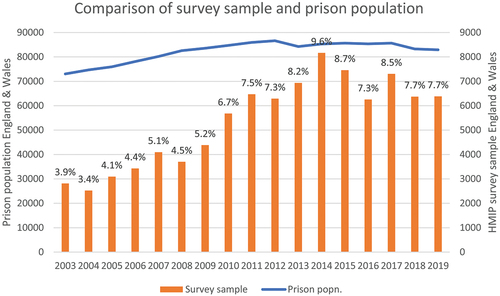

HMIP uses a random sampling method within each prison being inspected, covering all prisoners regardless of their period of incarceration, but prisons are sampled for inspection for a range of operational reasons with each prison inspected at least once every five years and most every two to three years (Reising et al., Citation2023). Overall, the sample is approximately 6% of the adult prison population () with consistently over 7% per year since 2010 as compared with the prison population numbers (Sturge, Citation2022).

Further details on the survey, the data, and associated user guide and data dictionaries are archived with the UK Data Service, and researchers can apply to use the data under Special Licence (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Citation2023). The analysis in this article uses these HMIP survey data for English prisons over the period 2003–2019, representing a total of over 86000 survey respondents, from more than 600 HMIP inspections of 149 prisons, with most of these being inspected and surveyed more than once during this period.

The archived datasets are primarily annual and were therefore merged to create a dataset covering the whole period. There have been eight main versions of the survey over this period (Reising et al., Citation2023), with changes ranging from minor rewording of questions or response options to significant inclusions or exclusions of sections and/or questions. Compatibility over time for the variables considered here was therefore achieved by deriving variables as required. For example, there have been five different classifications of age response categories used since 2000, so a derived age variable with five categories that could be derived from all the other versions is used here to enable consistent analysis over time. Questions on ease of access or quality have used different classifications of a range, with or without a middle value of ‘neither’, and so responses were grouped to derive variables of three-part categories of easy/difficult/don’t know-not been and categories of good/bad/not been-don’t know to be able to use the question responses over as many years as possible. The data would only allow more nuanced analysis over shorter timeframes than the seventeen years considered here.

The variables used are all nominal, and so non-parametric tests were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 23, using cross-tabulations, chi-square statistics, and Cramer’s V or Phi nominals to identify statistically significant associations. To avoid reporting results that were more likely chance occurrences, there is no reporting of observed or expected counts of less than five in cross-tabulation cells, or where adjusted standardised residuals are under ± 2.0. The primary focus of this article is change and trends over time, and so cross-tabulation enabled identification of significant trends over time, which are then presented visually as graphs to highlight the key findings.

The HMIP prisoner survey data provide evidence for several aspects of healthcare provision in prisons discussed in the literature above. In addition, they provide evidence across all adult prisons in England and Wales, and over more than 20 years, which is key to identifying the impact (or not) of changes in healthcare policy over this period. Given the different arrangements for NHS management in Wales, the analysis here is only for English adult prisons, and the period considered is 2003–2019, to avoid the impact of COVID-19 restrictions potentially confusing any trends identified (HMIP, Citation2020, Citation2021c; Wainwright et al., Citation2023). As a result, there is a total of 86,958 prisoner surveys analysed (85,121 from the six main functional types of prison considered in the analysis), though not all relevant healthcare questions were asked over the whole period and there are missing values on all variables.

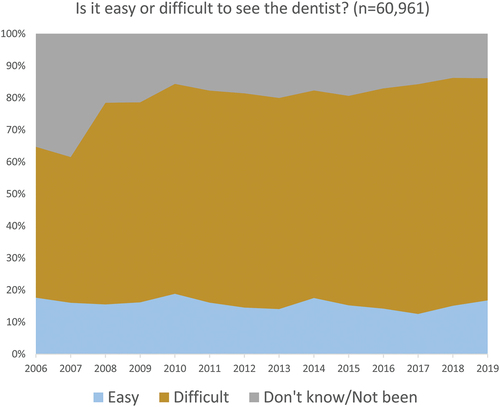

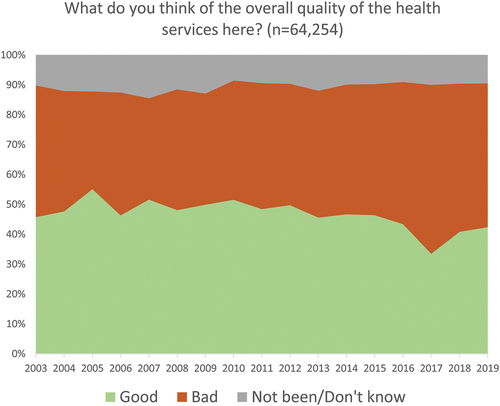

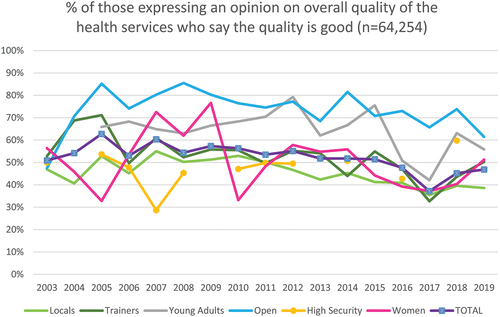

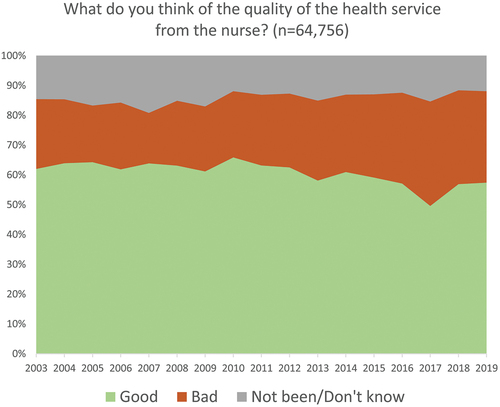

The key aspects of healthcare provision analysed are prisoners’ access to healthcare on arrival, ease of access to nurse, doctor, and dentist whilst in prison, and the quality of the healthcare service overall, and from nurse, doctor, and dentist. This is survey data, enabling prisoners to self-report their health needs and experiences, which has the limitations of being self-reporting, and potential issues of recall (such as remembering back to initial experiences on prison arrival). Initial access is evidenced from the questions ‘On your day of arrival, were you offered information about health services?’ which was asked from 2008 to 2016 (n = 47,908), and ‘Before you were locked up, were you offered the chance to see someone from healthcare?’ which was asked from 2003 to 2019 (n = 79,567). Access to healthcare is evidenced from the questions ‘Is it easy or difficult to see the nurse/doctor/dentist?’ which were asked from 2006 to 2019 (n = 58,715, n = 60,196, n = 60,961). The quality of healthcare is evidenced from the questions ‘What do you think of the overall quality of the health services here?’ and ‘What do you think of the quality of the health service from the nurse/doctor/dentist?’ which were asked from 2003 to 2019 (n = 64,254, n = 64,756, n = 66,011, n = 64,879). In addition to analysing changes over time in these variables, health needs over time were evidenced from the questions ‘Did you have health problems when you first arrived?’ (n = 75,833), ‘Do you consider yourself to have a disability?’ (n = 75,091) and ‘Are you currently on medication?’ (n = 56,037). Differences were tested for statistically significant associations with characteristics of prisoners (age, ethnic origin, sex, and conviction status), and the main functional types of prison (Locals, Trainers, Young Adults, Open, High Security, Women).

Results and discussion

shows the demographic categories of the survey data, with the percentage breakdown for the question on initial health problems. Cross-tabulation analyses indicate statistically significant differences between these demographic categories, however the Phi or Cramer’s V values are provided to show that the magnitude of the effect is often relatively small. Where Phi or Cramer’s V is greater than 0.1, the differences between categories are more notable.

Table 1. Categories of demographic characteristics and sentencing status of prisoners.

Health needs of prisoners

Women (females in Women’s prisons) were more likely to report having health problems than males (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 536.966, Phi = 0.084, n = 75,833) with 39% of women reporting health problems on arrival, compared with 26% of men. Women were more likely to identify as disabled − 29% compared with 23% (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 103.494, Phi = 0.037, n = 75,091) – and were much more likely to report being currently on medication: 71% compared with 47% (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1022.070, Phi = 0.135, n = 56,037). There is no significant difference on receiving information about healthcare on arrival, but women, with their greater likelihood of health problems, were more likely to be offered to see someone from healthcare before being first locked up (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 75.107, Phi = 0.030, n = 81,334).

Older prisoners were more likely report having had health problems on arrival (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1034.617, Cramer’s V = 0.117, n = 75,173), to be disabled (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 2638.932, Cramer’s V = 0.188, n = 74,487), and to be currently on medication (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 4684.131, Cramer’s V = 0.290, n = 55,577). Self-reported health problems were high, with over a third of prisoners over 50 (37%) reporting health problems on arrival, compared with 21% of 21–29 year olds. Nearly half of the over 50s (44%) reported a disability compared with 16% of 21–29 year olds, and over two-thirds of the over 50s (83%) were currently on medication compared with a third (34%) of 21–29 year olds. Despite being more likely to have health problems, over 50s were slightly less likely to recall having been offered information about healthcare on arrival (p < 0.05, Chi-Square = 9.915, Cramer’s V = 0.014, n = 49,824), and less likely to report having been offered to see someone from healthcare (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 337.173, Cramer’s V = 0.062, n = 87,549), especially in comparison with 30–39 year olds.

For comparison over time only the broad five category variable of ethnic origin can be used, and White prisoners were more likely to report having health problems on arrival (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 404.352, Cramer’s V = 0.074, n = 74,565), to be disabled (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1070.180, Cramer’s V = 0.120, n = 74,042), and to be currently on medication (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 979.441, Cramer’s V = 0.133, n = 55,130). Over a quarter of White prisoners reported health problems on arrival (29%) compared with Mixed Race prisoners (24%), Asian (21%), and Black (21%). Over a quarter of White prisoners reported being disabled (26%) with the statistically significant other categories as Mixed Race (19%), Chinese (15%), Black (15%), and Asian (12%). Over half of White prisoners reported being currently on medication (53%) compared with Asian (40%), Chinese (39%), Mixed Race (38%), and Black (36%). In keeping with their greater likelihood of reported health problems, White prisoners were more likely to receive information about healthcare on arrival (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 29.883, Cramer’s V = 0.025, n = 49,333), and more likely to be offered to see someone from healthcare (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 193.838, Cramer’s V = 0.047, n = 86,839), especially in comparison with Asian or Mixed Race prisoners.

Prisoners’ status had a statistically significant weak association with health needs, with Convicted prisoners less likely to have health problems on arrival (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 372.897, Cramer’s V = 0.071, n = 74,858), less likely to be disabled (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 75.540, Cramer’s V = 0.032, n = 74,069), and less likely to be currently on medication (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 14.110, Cramer’s V = 0.016, n = 55,299) than prisoners on Remand or awaiting Deportation.

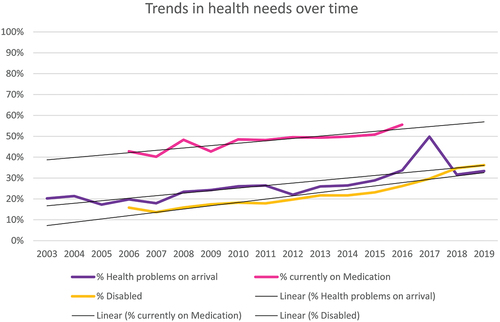

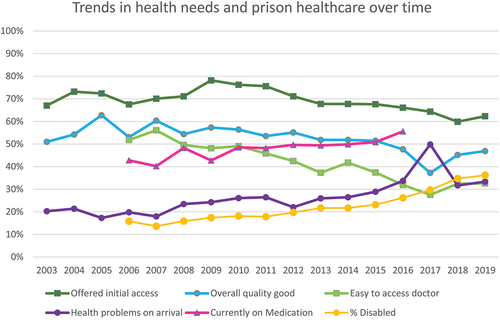

In terms of the main focus of this article, the indicators of health needs show a statistically significant trend of increasing health needs of prisoners over time (), with health problems on arrival rising from around a fifth in 2003 to a third in 2019 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1598.639, Cramer’s V = 0.147, n = 74,112), and being on medication rising from a minority in 2006 to a majority in 2016 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 308.644, Cramer’s V = 0.075, n = 55,365). Whilst disability may be an access need and/or a health need, there is a similar trend of increase over time of prisoners considering themselves to have a disability (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1691.275, Cramer’s V = 0.152, n = 73,543) from under a sixth in 2006 (16%) to over a third (36%) in 2019.

Access to healthcare on arrival

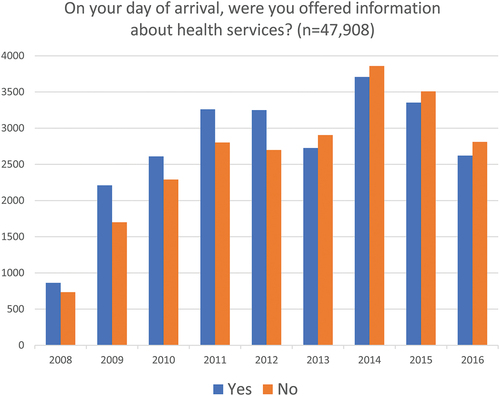

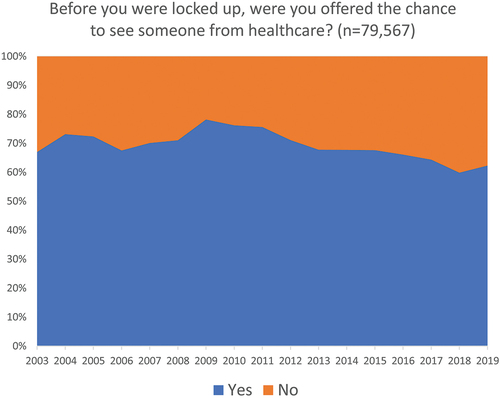

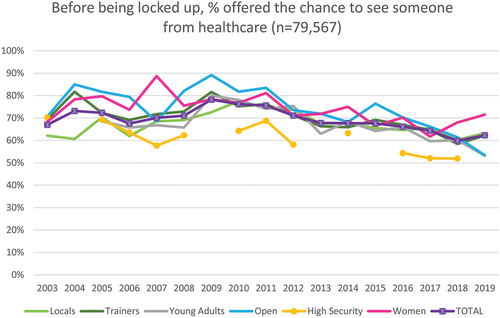

The NICE guidelines (Bradshaw et al., Citation2017, pp. 1–3; NICE, Citation2016) currently require all prisoners to receive an initial healthcare assessment before being allocated to a cell. Whilst not all prisoners might consent to this offer (Niveau, Citation2007, p. 611), all should be offered it. It is therefore notable that only around half (51%) of the prisoners surveyed in English prisons reported being offered information about health services on their day of arrival, and almost one third (31%) reported having had no access to someone from healthcare before they were locked up. Difficulties in initial healthcare access were an aspect identified in the recognition of the need for improvements in prison healthcare discussed above, and in the reorganisations carried out, but it is notable that the trend over time is one of worsening initial access.

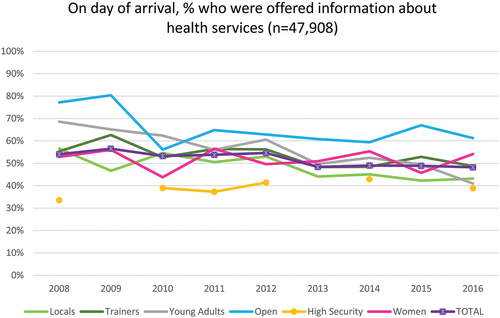

In terms of prisoners being offered information about health services on arrival (), the worsening trend is statistically significant (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 167.939, Cramer’s V = 0.059, n = 47,908) with the year 2013 – the year of healthcare management shift to NHS England – being marked by a shift from the majority having been offered information to a majority not receiving information about healthcare services on arrival.

Whilst this worsening trend is evident across all prison types, Open, Trainers, and Young Adults prisons tend to be above average in offering health services information, and Locals and High Security tend to be below average ().

A similar trend () – contrary to the NICE requirements and the intention of improving prisoners’ access to healthcare – is statistically significant on being offered the chance to see someone from healthcare before being first locked up (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 853,785, Cramer’s V = 0.104, n = 79,567). Here, the downward trend from around 70% being offered this in 2003 to just over 60% by 2019 (when it should be 100%), does include a small increase following the reorganisation from the Prison Medical Service to Department of Health in 2006, but a fairly consistent decline from 2009 despite the 2013 reorganisation.

Whilst this worsening trend is across all prison types, Open and Women’s prisons tend to be above average in offering access to someone from healthcare, and High Security tend to be below average, with Locals improving towards the average in 2010 and then falling along with the average thereafter ().

Access to healthcare whilst in prison

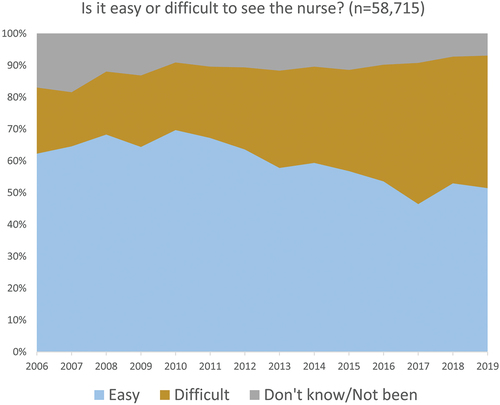

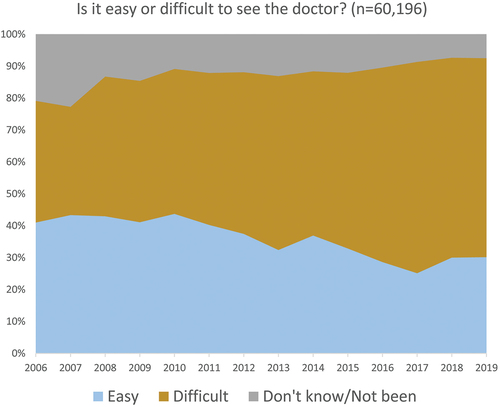

The issue of prison officers as (non-medical) gatekeepers for prisoners’ access to healthcare professionals has been noted above, as well as the bureaucracy of procedures (Condon et al., Citation2007), and the fact that different professionals – specifically nurses – may be easier to access. This differential ease of access is confirmed in the analysis here, with – in 2019–42% of the prisoners finding nurses difficult to access, compared with 62% finding doctors difficult to access, and 69% finding dentists difficult to access.

Again, the trend is of a statistically significant worsening access to healthcare professionals, with difficulty in seeing the nurse () rising from 21% in 2006 to a peak of 44% in 2017 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 2004.262, Cramer’s V = 0.131, n = 58,715). Prisoner self-reports indicate an overall rise in easy access from 2006 to 2010 is followed by a fairly consistent decline thereafter, with the reorganisation in 2013 seeming to have little positive effect.

A similar trend for ease of access to doctors () is statistically significant with reported difficulties in seeing the doctor rising from 38% in 2006 to a peak of 66% in 2017 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1908.891, Cramer’s V = 0.126, n = 60,196).

The trend for ease of access to dentistry () is similar and statistically significant with difficulty in seeing the dentist rising from 47% in 2006 to a peak of 72% in 2017 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 1480.524, Cramer’s V = 0.110, n = 60,961). Again, there is no clear indication of significant improvement following the 2013 reorganisation, though, in terms of the principle of healthcare equivalence, it may be worth noting that access to NHS dentistry is not easy anywhere (Garratt, Citation2023).

Quality of the healthcare service

The 2006 reorganisation aimed to improve the quality of healthcare provision, including ensuring all doctors were qualified GPs (Ginn, Citation2012), however, again, the analysis here is that prisoners experiences are of generally worsening quality over time. On the overall quality of health services (), the trend is of increasingly good from 46% good in 2003 to 55% good in 2005, and then down below half and a lowest point of a third (34%) reporting good in 2017, with a small rise thereafter (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 754.719, Cramer’s V = 0.077, n = 64,254). The shift from consistently more prisoners saying health services are good than bad (2003–2015) comes in 2016, with more saying it is bad than good thereafter. There is no sustained improvement after the reorganisation in 2006, and a continuing worsening after the reorganisation in 2013 with the lowest point in 2017 and slight improvement since, though still more prisoners saying the quality is bad than good.

Different types of prisons show similar trends, but prisoners report overall quality of health services being consistently above average quality in Open and Young Adults prisons, and below average in High Security and Local prisons ().

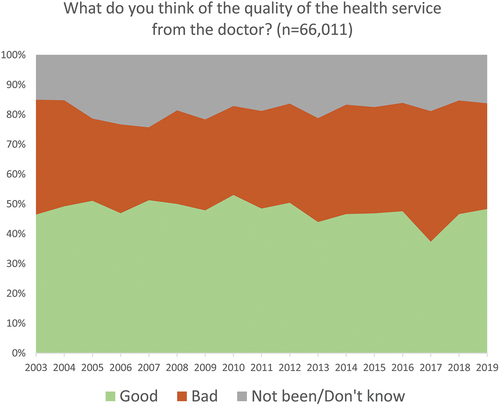

In terms of the quality of the service from different healthcare professionals, nurses are considered good by over half the prisoners (), except in 2017 (49.6%) (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 774.699, Cramer’s V = 0.077, n = 64,756), and doctors are more often considered good than bad (), with a lowest point of 37% good in 2017 (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 656.681, Cramer’s V = 0.071, n = 66,011).

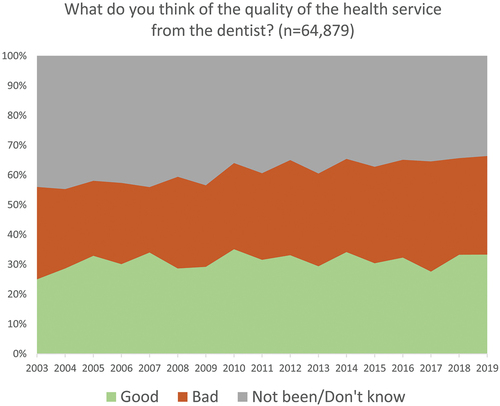

Prisoners have less experience of seeing the dentist than other healthcare professionals, and after early improvements in quality from 2003 to 2010, there remains about a third of prisoners assessing the quality as good (around half of those who express an opinion on quality) (p < 0.001, Chi-Square = 519.381, Cramer’s V = 0.063, n = 64,879) ().

What is clear is that, for these different healthcare professionals, prisoners have not experienced a significant improvement in quality from the reorganisations in either 2006 or 2013.

Conclusion

These survey data provide an unprecedented opportunity to analyse trends over time in prisoners’ self-reported experiences and assessments of the access to and quality of healthcare (as well as the potential analysis of prisoners’ experiences on a wide range of other issues). Aspects of healthcare are evidenced before and after the 2006 shift from the Prison Medical Service to Department of Health provision and before and after the 2013 reorganisation in England to NHS England healthcare provision. The stated aims of these policy changes and reorganisations were to improve healthcare for prisoners and develop increasing equivalence to the healthcare access and quality in the wider community. Prisoners, and particular groups within the prison population, were also recognised as having distinct healthcare needs. Whilst direct comparison with trends in healthcare in the wider community is not possible with these data, it is clear that major improvements on healthcare within prisons have not been achieved from the perspective of prisoners.

This period has seen reductions in prison funding, increases in prisoner numbers, and increases in prisoner healthcare needs. However, summarises the earlier graphs in showing that the upward trends of needs have been met by downward trends of initial access, ongoing ease of access, and ongoing quality of healthcare. Minimum standards are apparently not being met, with under 70% of the prisoners reporting being offered the initial health assessment that should be offered to 100% of prisoners. The downward trends do show a slight improvement from 2018 to 2019, but the COVID-19 restrictions from March 2020 (including the suspension of HMIP surveys for a period) will have affected the more recent period, and it cannot therefore be said yet whether improvements will be achieved or sustained.

Figure 15. Trends over time of prisoner health needs and access and quality of healthcare provision.

The overall conclusion of this analysis is, therefore, that the policy changes of prison healthcare provision reorganisations in 2006 and 2013 do not appear to matter much to prisoner experiences of or access to healthcare. The changes do not appear to have achieved sustained or significant improvements in access or quality, nor even to have levelled off worsening trends. Prisoners have distinctive, high, and increasing healthcare needs, but these have not been met by equivalent improvements in healthcare provision in prisons in England.

Author contributions statement

Janet C. Bowstead and Rosie Meek are the authors, making substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and acquisition of the data, with Janet C. Bowstead taking the lead on its analysis and interpretation. Both authors were involved in drafting the work and reviewing it critically, in final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

Thanks also to Nick Hardwick and Kim Reising, also at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in UK Data Service. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-9068-2, reference number 9068.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bradshaw, R., Pordes, B. A. J., Trippier, H., Kosky, N., Pilling, S., & O’Brien, F. (2017). The health of prisoners: Summary of NICE guidance. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 356(j1378), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1378

- Condon, L., Hek, G., & Harris, F. (2007). A review of prison health and its implications for primary care nursing in England and Wales: The research evidence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(7), 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01799.x

- Condon, L., Hek, G., Harris, F., Powell, J., Kemple, T., & Price, S. (2007). Users’ views of prison health services: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(3), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04221.x

- Cornford, C. S., Mason, J., Buchanan, K., Reeves, D., Kontopantelis, E., Sibbald, B., Thornton-Jones, H., Williamson, M., & Baer, L. (2008). A survey of primary and specialised health care provision to prisons in England and Wales. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 9, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423608000583

- Davies, M., Keeble, E., & Hutchings, R. (2021). Injustice? Towards a better understanding of health care access challenges for prisoners. Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/injustice/towards-a-better-understanding-of-health-care-access-challenges-for-prisoners

- Davies, M., Rolewicz, L., Schlepper, L., & Fagunwa, F. (2020). Locked out? Prisoners’ use of hospital care. Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/locked-out-prisoners-use-of-hospital-care

- de Viggiani, N. (2006). A new approach to prison public health? Challenging and advancing the agenda for prison health. Critical Public Health, 16(4), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590601045212

- de Viggiani, N. (2007). Unhealthy prisons: Exploring structural determinants of prison health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 29(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00474.x

- de Viggiani, N., Orme, J., Powell, J., & Salmon, D. (2005). New arrangements for prison health care: Provide an opportunity and a challenge for primary care trusts. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 330(7497), 918. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7497.918

- DHSC. (2019). Government response to the Health and Social Care Committee’s inquiry into prison health (CP 4). Department of Health and Social Care. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prison-health-inquiry-government-response

- Garratt, K. (2023). NHS dentistry in England [ CBP 9597]. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9597/

- Ginn, S. (2012). The challenge of providing prison healthcare. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 345(7875), 26–28.

- Glorney, E., Jablonska, A., Wright, S., Meek, R., Hardwick, N., & Williams, W. H. (2018). Brain injury linkworker service evaluation study: Technical report for the disabilities trust and barrow cadbury trust. The Disabilities Trust. https://www.thedtgroup.org/media/163449/full-independent-evaluation-royal-holloway.pdf

- Harris, F., Hek, G., & Condon, L. (2006). Health needs of prisoners in England and Wales: The implications for prison healthcare of gender, age and ethnicity. Health & Social Care in the Community, 15(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00662.x

- HM Government. (2019). National prison healthcare board principle of equivalence of care for prison healthcare in England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/837882/NPHB_Equivalence_of_Care_principle.pdf

- HM Government, & NHS England. (2018). National partnership agreement for prison healthcare in England 2018–2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/767832/6.4289_MoJ_National_health_partnership_A4-L_v10_web.pdf

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons. (2023). HMIP prisoner survey: Adults in England and Wales, 2000–2022: Special licence access [ dataset]. UK Data Service. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-9068-1

- HMIP. (2014). HM chief inspector of prisons for England and Wales annual report 2013–14. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/inspections/annual-report-2013-2014/

- HMIP. (2020). Developing HMI prisons scrutiny during recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. HM Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/08/SV-methodology-for-website-1.pdf

- HMIP. (2021a). Expectations: Criteria for assessing the treatment of and conditions for men in prisons. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2021/07/Expectations-FINAL-2021.pdf

- HMIP. (2021b). Expectations: Criteria for assessing the treatment of and conditions for women in prison. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/our-expectations/womens-prison-expectations/

- HMIP. (2021c). What happens to prisoners in a pandemic? A thematic review by HM inspectorate of prisons. HM Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/inspections/what-happens-to-prisoners-in-a-pandemic/

- HMIP. (2023a). Detainee survey. HM Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/about-our-inspections/research/detainee-survey/

- HMIP. (2023b). Inspection framework. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/Inspection-framework-2023.pdf

- HMPPS. (2014). Healthcare for offenders: how offender healthcare is managed in prisons and in the community. HM Prison and Probation Service. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/healthcare-for-offenders

- Home Office. (1996). Patient or prisoner? https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/inspections/patient-or-prisoner/

- House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee. (2018). Prison health: Twelfth report of session 2017–19. HC 963. House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/963/963.pdf

- House of Commons Justice Committee. (2019). Prison population 2022: Planning for the future [ HC 483]. House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmjust/483/483.pdf

- Hutchings, R., & Davies, M. (2021a). How prison health care in England works. Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/prison-health-care-in-england

- Hutchings, R., & Davies, M. (2021b). Literature review: Towards a better understanding of health care access challenges for prisoners. Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/injustice-towards-a-better-understanding-of-health-care-access-challenges-for-prisoners

- Ismail, N. (2019). Rolling back the prison estate: The pervasive impact of macroeconomic austerity on prisoner health in England. Journal of Public Health, 42(3), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz058

- Ismail, N. (2020). Deterioration, drift, distraction, and denial: How the politics of austerity challenges the resilience of prison health governance and delivery in England. Health Policy, 121(12), 1368–1378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.09.004

- Ismail, N., & de Viggiani, N. (2018a). Challenges for prison governors and staff in implementing the healthy prisons Agenda in English prisons. Public Health, 162, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.06.002

- Ismail, N., & de Viggiani, N. (2018b). How do policymakers interpret and implement the principle of equivalence with regard to prison health? A qualitative study among key policymakers in England. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44(11), 746–750. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2017-104692

- Leaman, J., Richards, A. A., Emslie, L., & O’Moore, E. J. (2017). Improving health in prisons – from evidence to policy to implementation – experiences from the UK. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 13(3–4), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-09-2016-0056

- McLeod, K. E., Butler, A., Young, J. T., Southalan, L., Borschmann, R., Sturup-Toft, S., Dirkzwager, A., Dolan, K., Kofi Acheampong, L., Topp, S. M., Elwood Martin, R., & Kinner, S. A. (2020). Global prison health care governance and health equity: A critical lack of evidence. American Journal of Public Health, 110(3), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305465

- MOJ. (2020a). Ministry of justice: Areas of research interest 2020. Ministry of Justice. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ministry-of-justice-areas-of-research-interest-2020

- MOJ. (2020b). Story of the prison population 1993–2020. England & Wales. Ministry of Justice. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/930166/Story_of_the_Prison_Population_1993-2020.pdf

- NICE. (2016). Physical health of people in prison: NICE guideline NG57. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng57

- NICE. (2017). Mental health of adults in contact with the criminal justice system: NICE guideline NG66. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng66

- Niveau, G. (2007). Relevance and limits of the principle of “equivalence of care” in prison medicine. Journal of Medical Ethics, 33(10), 610–613. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2006.018077

- Piper, M., Forrester, A., & Shaw, J. (2019). Prison healthcare services: The need for political courage. British Journal of Psychiatry, 215, 579–581. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.43

- Powell, J., Harris, F., Condon, L., & Kemple, T. (2010). Nursing care of prisoners: Staff views and experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(6), 1257–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05296.x

- Quinn, A., Denney, D., Hardwick, N., Jalil, R., & Meek, R. (2022). The feasibility and challenge of using administrative data: A case study of historical prisoner surveys. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(1), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1853877

- Quinn, A., Shaw, C., Hardwick, N., Meek, R., Moore, C., Ranns, H., & Sahni, S. (2020). Prisoner interpretations and expectations for the ethical governance of HMIP survey data. Criminal justice ethics, 39(3), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/0731129X.2020.1859298

- Reed, J., & Lyne, M. (1997). The quality of health care in prison: Results of a year’s programme of semistructured inspections. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 315(7120), 1420–1424. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1420

- Reising, K., Bowstead, J. C., Hardwick, N., Meek, R., Riley, S., & Simmonds, J. (2023). HMIP prisoner survey: Adults in England and Wales. User manual (1st ed.). Royal Holloway, University of London. https://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/9068/mrdoc/pdf/9068_hmip_prisoner_survey_user_guide_volume_a_20230531.pdf.

- RHUL. (2023). Secondary analysis of data collected over a 20 year period by HM inspectorate of prisons. Royal Holloway, University of London. https://royalholloway.ac.uk/research-and-teaching/departments-and-schools/law-and-criminology/research/our-projects-and-research-impact/secondary-analysis-of-data-collected-over-a-20-year-period-by-hm-inspectorate-of-prisons/

- Rogalska, A., Barański, K., Rachwaniec-Szczecińska, Ż., Holecki, T., & Bąk-Sosnowska, M. (2022). Assessment of satisfaction with health services among prisoners—descriptive study. Healthcare, 10(548), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030548

- Sim, J. (2002). The future of prison health care: A critical analysis. Critical Social Policy, 22(2), 300–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183020220020701

- Sturge, G. (2022). UK prison population statistics. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04334/SN04334.pdf

- Till, A., Forrester, A., & Exworthy, T. (2014). The development of equivalence as a mechanism to improve prison healthcare. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107(5), 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814523949

- Wainwright, L., Senker, S., Canvin, K., & Sheard, L. (2023). “It was really poor prior to the pandemic. It got really bad after”: A qualitative study of the impact of COVID-19 on prison healthcare in England. Health & Justice, 11(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-023-00212-1

- Woodall, J. (2016). A critical examination of the health promoting prison two decades on. Critical Public Health, 26(5), 615–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2016.1156649

- Woodall, J., & Freeman, C. (2020). Promoting health and well-being in prisons: An analysis of one year’s prison inspection reports. Critical Public Health, 30(5), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1612516

- Zaitzow, B. H., & Willis, A. K. (2021). Behind the wall of indifference: Prisoner voices about the realities of prison health care. Laws, 10(11), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws10010011