ABSTRACT

Given the fact that women in homelessness face considerable health inequities, the question of how digitalization can be understood in relation to social rights and right to health surfaces. The objective of this qualitative interview study was to explore the use of mobile phones and internet for women experiencing homelessness. Women (n = 26) shared experiences of healthcare access by using a mobile phone or internet. Data were analyzed using NVivo software. The results are presented in two themes: Conditions and circumstances of having a mobile phone; and Structural and intrapersonal challenges affecting social rights. The results show that digitalization actively influenced everyday life for women experiencing homelessness. Whether women wanted it to or not, digitalization presents a line of demarcation for participation and inclusion or exclusion, in health- and social-care services.

Introduction

The digitalization of social and health care services has attracted considerable research interest from several different disciplines (Cuesta et al., Citation2020; De Rosa, Citation2017), but only to a limited extent from a social rights perspective and rarely with a focus on health in a particularly marginalized group like women experiencing homelessness. The idea of social rights goes far back in pre-digital times, to the broad push towards democracy and equal rights in many countries in the early 20th century. The fundamental rights to a basic level of welfare are not a matter of ‘charity’ or ‘solidarity’, but a necessary precondition for the exercise of civil and political rights, and for democracy itself (Marshall, Citation1950). Social rights comprise universal access to healthcare, education, housing, and social insurance, including financial aid. They are realized by public institutions, organizations, families, and individuals, and social rights, like civil and political rights, are ultimately the responsibility of the government. However, how social rights actually have been operationalized (or not), varies, and for women experiencing homelessness, these rights and access to resources are often unrealized. Women experiencing homelessness is an outsider group with sometimes limited or contested access to public health and welfare institutions, often more dependent on informal help and social support from their social network (McNaughton, Citation2008). Furthermore, digitalization reforms across health- and social-care agencies, public health and public-sector institutions put additional strain on people experiencing vulnerabilities (Schou & Pors, Citation2019). It is well established that varying access to digital technologies and varying ability for use leads to further inequality and social divides (Hansen et al., Citation2018; Leonardsen et al., Citation2020; Schou & Pors, Citation2019), in effect presenting a digital divide.

Unequal access to social rights perpetuates health inequities (Marmot et al., Citation2012), and since women experiencing homelessness are disproportionally affected by physical and mental illness, sexual violence, increased morbidity, and premature death (Aldridge et al., Citation2018; Chambers et al., Citation2014), this is urgent to address. In addition, gendered aspects of health, specifically for women experiencing homelessness, highlight prevalence of stress due to poor sleep, feelings of loneliness, and feeling unsafe (Buccieri et al., Citation2020). Women in homeless shelters were disadvantaged in comparison to men, reporting lower self-esteem, less satisfaction with health and higher psychological distress (de Vet et al., Citation2019). Thus, women’s experiences, needs, characteristics, and choices may be different from men’s and this may be significant when addressing public health aspects to promote right to health (Bretherton, Citation2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines e-Health as the use of information and communication technologies for health (WHO, Citation2018), further emphasizing that digitalization may be a way forward to promote universal health coverage and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, Citation2018). The SDGs adopted by all countries in the United Nations aim to end poverty with strategies to improve health and education, reducing inequality, promoting economic growth, and tackling climate change. With health equity in mind, it is crucial to focus attention and intensity of service initiatives on the people with the greatest needs (Marmot et al., Citation2012), like women experiencing homelessness (Aldridge et al., Citation2018; Kneck et al., Citation2021). The existing research on digitalization, like using mobile phones and the internet, in relation to homelessness indicates benefits of use for people experiencing homelessness (Calvo et al., Citation2019), without specifying circumstances for women. Even earlier research indicates that mobile phones contributed to feeling of safety and were used when searching for employment and to stay socially connected (Eyrich-Garg, Citation2010), at the time, with about 44% having access to a mobile phone. In the same group, 47% reported using a computer in the past 30 days (Eyrich-Garg, Citation2011). The main reasons for using a computer were similarly for business purposes (employment, housing, or scholarships), for leisure and for social connectedness. At this time, no participants reported using their mobile phone or the internet to contact healthcare services.

Later, research on homelessness and digital technology highlights the innovative uses of digitalization through better access to health services (Jiménez-Lérida et al., Citation2023), and by breaking social isolation (Neale & Brown, Citation2016; VonHoltz et al., Citation2018). A bibliometric review, indicates that mobile phones and internet use provide a way to seek for social support, to follow health processes with health care professionals, and to allow relationship connections away from the harsh reality on the streets (Calvo et al., Citation2019). However, findings from an ethnographic study, specifically with women experiencing homelessness and multiple, complex problems, including deep social exclusion, underscore the challenges of lacking stable access to a mobile phone and describe how the transactional value of the mobile phone may supersede connectivity when needing funds (Williams et al., Citation2023). These women also described how ‘strategic disconnect’, by hiding the mobile phone or leaving it behind, may represent both protection of resources and protection from stigma by avoiding social media connections. The health issues that people experiencing homelessness most commonly sought help for, using digital technology, were substance use, mental health needs, gender-based violence, and smoking cessation (Vazquez et al., Citation2015).

Some people experiencing homelessness don't seem to be concerned with e-Health services at all (Vazquez et al., Citation2015). This, in turn, may be explained by the fact that the ability to use e-Health services presupposes e-Health literacy, which has been described in a conceptual model (Norgaard et al., Citation2015). The model provides insight into e-Health literacy from the perspective of the individual and the system as well as the intersection between the two. The individual perspective includes the ability to process information and furthermore, engagement in one’s own health. From the perspective of the system, e-Health literacy requires both access to digital services that work and digital services that suit individual needs. The interaction and relation between the individual and the system, focus on the ability to actively engage with digital services, feeling safe and in control, and finally being motivated to engage with digital services. Considering women experiencing homelessness and the demands of e-Heath literacy, presupposing both digital resources and abilities, the requirements to use e-Health services and realize social rights may present a barrier. Naturally, another reason for not engaging with e-Health services is that people experiencing homelessness generally have poor access to routine healthcare (Fazel et al., Citation2014; Grammatikopoulou et al., Citation2021), often seeking healthcare late in their condition- or disease- trajectory.

To summarize, women experiencing homelessness encounter significant health disparities, highlighting the need to examine how ongoing digitalization efforts intersect with the realization of social rights and the right to health for this marginalized and underserved population. Recognizing that the responsibility for ensuring social rights lies with governments and societies, rather than solely with the women themselves, prompts questions about how digital technologies, such as mobile phones and the internet, are utilized to access healthcare and social services. Understanding the role of digitalization in the lives of women experiencing homelessness is essential for addressing health inequities and advancing social justice in a digital society.

Objective

The objective of this study was to explore the use of mobile phones and the internet among women experiencing homelessness, with a focus on how these digital tools contribute to accessing healthcare and social services.

Methods

Design

This study comprised a qualitative, descriptive, and inductive approach, and is part of a research program striving to promote health for women experiencing homelessness.

Setting and participants

Sweden has a population of 10 million people and universal healthcare insurance. The country has taken digitalization to heart, leading to the government establishing The Swedish National Digitalisation Council in 2017 (Digitaliseringsrådet, Citation2019), with the explicit goal of being the best in the world at utilizing opportunities with digitalization, for example with regard to healthcare services and access. In 2019, 91% of the Swedish population used the internet daily and 93% of households have a computer (Digitaliseringsrådet, Citation2019). With regard to having a mobile phone, 99% of the population report having a phone of their own. Electronic identification comparable to a passport, driver’s license, or other physical identification document, so-called electronic ID, has been implemented on a large scale, with 84% using electronic ID. Examples of electronic ID use are formal identification online for filing tax returns, conducting bank affairs and making appointments with authorities, including health- and social-care services. Although the majority of the Swedes use the internet on a daily basis, it is important to bear in mind that over one million people in Sweden have no access to the internet nor digital devices, such as mobile phones or tablets.

In Sweden, around 27 000 individuals were reported experiencing homelessness in 2024 and around 32% were women, with a mean age of 39 years (Welfare, 2024). According to the report, the number of women, women born abroad, and women with children under 18 years of age had increased over a six-year period.

The women in this study were recruited to a primary healthcare center in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden (Stockholm County population 2.4 million). The center is open on weekdays and is the only designated healthcare center for individuals experiencing homelessness within the region, though, healthcare services in general are for all persons with healthcare needs. Visits are free of charge and a wide range of health services are offered, without requiring pre-booked appointments nor formal identification. The healthcare center has collaborations with social services, primary and psychiatric care, and services for treatment of substance use disorder. Around 14 000 visits are completed each year, with approximately 1300 patients, of which 40% are women. Social services are located in adjacent rooms, with a joint waiting area for persons seeking healthcare and/or social services.

The researchers contacted the healthcare center, presenting our study and the ethical approval, asking for permission to collect data from women. The responsible medical director agreed and suggested a research assistant to act as guide, both to the facilities and also to assist with recruitment. The research assistant was experienced in working at the healthcare center and had access to all facilities.

Convenience sampling was used, and one researcher (first or third author) and a research assistant were present in the waiting area. When potential participants, i.e. women, arrived in the waiting area, they were approached, greeted, given information about the study and invited to participate in interviews. We stated that we were interested in talking to women with experiences of homelessness about their experiences of healthcare. Sometimes this entailed chatting a while about the weather or daily occurrences in the waiting area, before proceeding to the interview room.

Inclusion criteria were for women with experiences of homelessness, speaking Swedish or English. Exclusion criteria were for women exhibiting extreme distress or anxiety, manifested as violent or abusive behavior. If a woman consented to participate, further written and verbal information was given in the interview room, located next to the waiting area. At the start of interviews, the interviewer reiterated that the woman could leave the room and discontinue the interview at any time without repercussions. The two researchers (first and third author) had extensive experiences of qualitative interviewing, however, not with this population. Interviews were performed with 26 women (English speaking n = 2) and were regarded as sufficient to provide data related to the aim. The same sample was used in another study to explore perspectives of healthcare services, please refer to (Kneck et al., Citation2021). The broad definition of homelessness developed by the European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion (ETHOS) was used to describe variations of homelessness (FEANTSA, Citation2023). Self-reported sociodemographic data are presented in .

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the interviewed women (n = 26).

The women were between 23 and 65 years of age, with a median age of 46 (range 42). Most women were houseless (70%), and all had experiences of homelessness. Three women had housing provided by social services, and over half (66%) reported being unemployed or on sick leave.

Data collection

To meet the purpose of our study, we gathered data through qualitative, semi-structured interviews, using a narrative approach (Fraser, Citation2004). Building a safe atmosphere for sharing was facilitated by having coffee or tea together and chatting before the interviews (Price, Citation2002). Prior to interviews, written informed consent was obtained. An interview guide was developed with broad areas regarding the experiences of the accessibility of healthcare services, use of mobile phones and internet in general and to access healthcare- and social- services, see Appendix. Open-ended questions were asked, and women were encouraged to speak freely of situations and experiences that came to mind. The researcher was supportive and asked follow-up questions in order to help the women to elucidate their answers. The women in this study all self-reported living conditions with unsecure or non-existent accommodation, physical, cognitive and/or mental health issues, and/or ongoing substance use. However, all who met the inclusion criteria and wanted to participate were included, even though there were challenges in relation to participation for some. Examples of challenges were short attention span, feelings of restlessness, challenges with comprehension or focus. Interviews were audio recorded pending permission and interviews lasted between 9 and 34 minutes, mean 22 minutes. As a token of appreciation, participants received a voucher equivalent to about 20 Euro to a local grocery store. We conducted the interviews between August and November of 2019.

Data analysis

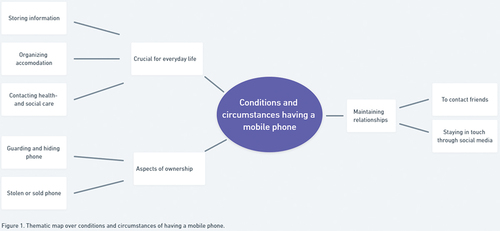

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional agency and subsequently analyzed with inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), comprising the steps: familiarization with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and finally producing the report. During the data analysis, we used NVivo software to facilitate systematic analysis across the data set. Interview data were divided so that data pertaining to use of mobile phones and internet was used in this study, while data regarding experiences of healthcare services was used and reported in another study (Kneck et al., Citation2021). All authors read the transcripts for all interviews, in Swedish or English depending on interview. English transcripts were analyzed without translation to Swedish. First author performed initial coding, which was discussed with second and last authors before searching for themes. The steps searching for themes and reviewing themes were similarly performed initially by first author, constructing thematic maps in NVivo for graphic presentation, and subsequently reviewed and discussed with second and last authors. See for an overview of raw data in relation to themes.

Table 2. Examples of raw data organized by themes.

The construction of thematic maps allowed an overview of the data and material, thus facilitating reviewing themes and organizing findings according to manifest content. The thematic maps were used in research group discussions and promoted sharing of data and analysis as it was ongoing. See and for the thematic maps.

As highlighted by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), analysis was not a linear process, rather a recursive process with movement back and forth among the steps. Refining the specifics of each theme and generating clear definitions of themes was similarly done and the final steps of analysis were conducted during the writing of the report. This final step involved all authors and was crucial to relate back to the research aim and the literature, while clearly illustrating the themes, subsequently enabling readers to assess the trustworthiness and credibility of the presented findings.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [AK], upon reasonable request.

Ethical considerations

In line with the Helsinki declaration (World Medical Association [WMA], Citation2013), informed consent was obtained from all participants by signing a document. Women who did not want to divulge their names, signed the consent form with ‘X’. No identifying personal information that could be connected to a specific woman was collected. All data were self-reported, and no medical files were accessed. Women experiencing homelessness often have challenging circumstances and experiences of abuse, trauma, and violence. Efforts were made to ensure availability of psychosocial support through the primary healthcare center, if needed, in association with the interviews.

All documentation of research data, including audio recordings and transcribed texts, were stored on a password protected server, only accessible to the research group. The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [AK]. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Ethical approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [no 2019-02130].

Results

Inductive thematic analysis revealed two themes which represent the embodiment of mobile phone and internet use among women in homelessness. The themes are presented in terms of: Conditions and circumstances of having a mobile phone; and Structural and intrapersonal challenges affecting social rights. Implications were that having mobile phones and internet access stipulated how interactions with public health- and social-care were executed and functioned, as well as maintaining social interactions and staying in touch with family and friends. It actively influenced everyday life, whether women wanted it to or not and presents a line of demarcation for participation and inclusion or exclusion, in health- and social-care services. See for an overview of themes and sub-themes.

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes of the results.

Conditions and circumstances of having a mobile phone

This theme addresses various expressions for women experiencing homelessness of having or missing a mobile phone. Women described that having a mobile phone was crucial for everyday life. The mobile phone was used for storing information, like contacts and phone numbers, maintaining contact to a regular physician, ultimately endorsing continuity of care. The mobile phone was also used for contacting health- and social-care services. For women who did not have access to a mobile phone, contacting services became very challenging.

The mobile phone was also used to get in touch with people and to arrange temporary accommodation, since being in homelessness entailed having to make your own way. Women could not rely on people around them for help. As one woman said:

But in homelessness, it’s mostly to … well to … to get in touch with people like … , and you may need a place to sleep and might have some places where you can stay. It is hard, I mean, people don’t trust you when you walk up, ‘Scuse me, may I use your phone? You can have my bag meanwhile’, but no … So … it’s important in many ways. (W14)

Owning a mobile phone in homelessness was described by women as difficult or even impossible. Circumstances of daily life for women experiencing homelessness entailed living in uncertain and unpredictable circumstances where a mobile phone also represented a valuable commodity that other persons would try to get for themselves.

It doesn’t work at all, mobile phone … , I think I’ve had about ten different ones, because as soon as you fall asleep they steal it, and it’s even my best friends on the street taking it, because they have the same need. (W18)

Commonplace in the narratives were experiences of mobile phones being lost or stolen, also by friends, since others experiencing homelessness have the same need for a mobile phone. For many women, having a mobile phone was dependent on managing to hide and protect the mobile phone,for example, by never using the mobile phone around others so that the existence was kept secret, a strategic disconnect.

I don’t ever have it up visible at all, so that people see, like when I … , I don’t take my phone up at all. I always keep it in a pocket, preferably an inner jacket pocket, so that … . Yeah, stuff like that, that I think about it, that I … In some instances, I don’t bring it all … And since I got a place to live, well, I leave my phone there instead. (W15)

An important function of having a mobile phone was maintaining relationships by keeping in touch with family and friends. Having a mobile phone allowed keeping in touch irrespective of circumstances. Furthermore, women could stay in touch without giving away details of their present situation, unless they wanted to. Sometimes this was done directly by using the mobile phone to call or to send text messages. Other times it was more indirect with the help of social media, and the mobile phone was instrumental for both these ways of maintaining relationships. The mobile phone is therefore a crucial instrument for keeping in contact with the type of social support systems that women in homelessness are particularly dependent on.

How about the mobile phone, do you feel like you need it?

Yes, I need it. My mom wants to know what happens, or if I’m alive or not. (W7)

But I have my family up north, I haven’t met anyone for ten years. I met one of my sisters maybe five years ago and I missed her last time since I hadn’t seen her email in time. I mean, it’s really important, to me it’s important … especially when I have somewhere to stay and stuff. I want to be able to get out on the internet. (W14)

In summary, this first theme comprised experiences of the conditions and circumstances of being in homelessness, in relation to having a mobile phone. Women emphasized that the mobile phone was crucial for everyday life and for practical matters, such as storing (in effect remembering) information, arranging accommodation, contacting health- and social care services, and maintaining social relationships. Having a mobile phone and access to internet services was a link to interactions in society and to upholding connections during precarious circumstances. However, having a mobile phone also entailed experiences of losing the phone, and strategies for guarding and hiding the phone in order to keep possession of the phone to stay connected.

Structural and intrapersonal challenges affecting access to social rights

In the second theme, experiences of structural and intrapersonal challenges affecting access to social rights were prevalent. Living in homelessness entailed a transient and uncertain existence with numerous structural challenges, such as access to electricity, wi-fi and personal, electronic identification. A prerequisite of using mobile phones and internet was having access to electricity in order to charge the battery. Moreover, the sporadic availability of wi-fi accentuates their vulnerability, as it limits their digital engagement and access to online resources.

Other structural challenges described were related to technical issues. Some women had access to mobile phones, but not smart mobile phones with the possibility of internet access. Mobile phones provided by the social services were often basic phones for making telephone calls or to use for rudimentary text messages.

I’ve lost six phones in three months, they got stolen so now I have a crappy phone for 40 Euros, that social services paid for me. (W7)

The mobile phones provided by the social services were not smartphones and could not be used to access internet services. Other women who did have smart mobile phones, often had limited credit requiring free wi-fi for internet use. In these circumstances, getting access to wi-fi could be difficult in more remote areas with reduced coverage.

The ability to make an electronic identification was another structural challenge. Obtaining an electronic ID requires both having technology requirements in place and also being able to identify yourself in person and keeping the same mobile phone, with the electronic ID, for a longer period of time. Taken together, these aspects comprised barriers on top of barriers for the women. If a phone was lost, stolen or sold, the electronic ID was lost too. The electronic ID was required to contact healthcare services to make appointments or renew medications. After being robbed of bank cards, used for payment, and the mobile phone, getting a healthcare appointment was challenging.

If I seek medical attention, that means contacting healthcare services, you need electronic ID, and that doesn’t work. Firstly, they take your bank cards and then you need to get new ones and if you can’t id yourself, then it takes … to get it all going, it takes half a year just to get a new one, and lose it again. So … it’s … I don’t bother with it anymore. (W18)

The structural aspects of obtaining and maintaining electronic ID posed significant obstacles and faced with these, some women decided it was not worth the trouble. Instead of accessing services, women were discouraged and found that obtaining and maintaining an electronic ID presented further obstacles to access society services. Other aspects of having a electronic ID were related to knowing how to use the technology surrounding electronic identification. For many women, this was unfamiliar territory and wanting instruction was highlighted.

Yes, electronic ID, but I have that through my bank if I want it, but I don’t know how it works so I need to take a course I think, to be in society and not feeling left out. Everything happens on a computer. (W1)

Intrapersonal challenges with using the internet were prevalent in the women’s narratives and some women expressed a strong dislike for digital services. Several women shared that they do not have the required knowledge about internet to be able to utilize the internet. Others had health issues comprising cognitive impairment and shared that this created a huge obstacle. Some women lacked knowledge about the internet since they had been experiencing homelessness since before the internet was widely used.

I mean internet, that’s just … that’s a big problem for me, because I’m not an internet user and I don’t have the knowledge needed, but I do have a regular [mobile] phone. (W17)

No, you know I’m a bit behind when it comes to using a computer. I haven’t kept up with … . (W23)

Other intrapersonal aspects were related to fear and anxiety in contacting authorities such as health- and social services. Sometimes this was due to having negative experiences from before that had resulted in reduced trust for authorities and society services. Women shared that this was challenging since most places do not accept walk-ins to make appointment, instead women were turned away and admonished to make their appointments online or through the telephone. As previously described, this presented structural challenges alongside the intrapersonal challenges of cognition or social anxiety.

Hmm, I do have something, and I have a really hard time to … I mean to call and talk to authorities and stuff. I don’t know, it not really awful, but I just feel like … Dad, can you please call for me … like that. (W16)

Several different strategies were used to navigate the system,for example, using email when contacting authorities and thus having an audit trail, since authorities, such as health- and social-services are required by law to store and archive electronic communication. This served two purposes, making sure that communication is documented and also, that it is clear what has been communicated from both sides.

Women used various strategies to find wi-fi,for example, turning to a shelter, the City Mission, asking a random person on the street, or a hotel reception. Another strategy used by women was finding a person to help with using the internet or a mobile phone to contact health- and social services. Women mentioned friends that they could turn to, emphasizing that these friends were not experiencing homelessness nor had issues with substance use. Other persons that could help were family members or staff in shelters, healthcare centers, or social services helpdesks. Women who had other people facilitating contacts emphasized how this made a difference and resulted in receiving care.

I’ve really gotten good care when I’ve needed to because I’ve had my parents help. They’ve called for me and stuff because I haven’t really had … I mean they’ve spent time in telephone ques holding. (W4)

In summary, the second theme comprised experiences of structural and intrapersonal challenges influencing access to social rights, such as health- and social services. Women highlighted that structural challenges could make contacting health- and social care services impossible, since access to a charged smartphone, wi-fi, electronic identification and knowledge about digital services was a prerequisite. Intrapersonal challenges presented obstacles in contacting and interfacing with health- and social care services through mobile phones and internet. Examples of challenges were lack of knowledge for navigating the internet, fear and anxiety in making phone calls, or health related issues like cognitive impairment. Women used multiple strategies to circumvent the challenges, using emails for an audit trail, relying on assistance from friends, family or shelter staff, and finding alternate internet access points.

Discussion

For women experiencing homelessness in this study, use of digital technology, such as mobile phones and internet, comprised challenges with finding internet connection, charging the devices, the risk of being robbed, and technical constraints. The Swedish National Digitalisation Council has highlighted that the greatest risk of digitalization is implementing digital solutions on a large scale, without ensuring that the recipients or the users, have the knowledge or the experience of how the technology works (Digitaliseringsrådet, Citation2019). These concerns were confirmed for the women in our study. In addition, women described structural problems with electronic ID or lacking a smartphone, for accessing digital technology and subsequently, digital services in society. The associated problems with accessibility and usability must be addressed. Otherwise, chances are that digitalization and e-Health hinders rather than enable realization of right to health for women experiencing homelessness.

Resources and e-Health literacy for digital services

Several of the women in our study were unfamiliar with general use of internet and did not have smart phones, thus presenting a stumbling block on the individual level of e-Health literacy. Individual competencies to utilize and benefit from digital services comprise the ability to process information and engagement in their own health (Norgaard et al., Citation2015). Prior studies have highlighted how people experiencing homelessness benefit from using digital technology (Calvo et al., Citation2019) in seeking health services, such as primary healthcare or psychiatric care. These examples all fall short when individuals do not have smartphones and furthermore, they rely on the persons’ engagement in their own health. This may be especially challenging in times of homelessness when struggles to meet basic human needs of food, safety, and shelter take precedence over health needs (Kneck et al., Citation2021). In this perspective, digitalization of welfare services acts to further alienate women experiencing homelessness, effectively blocking right to health. How this affects the already extenuating circumstances of health inequities and increased morbidity among persons in homelessness (Aldridge et al., Citation2018; Fazel et al., Citation2014) is unclear.

Digitalization and a systems perspective

What is clear, however, is that digitalization constitutes a new determinant of health, i.e. digital health equity (Crawford & Candlin, Citation2013). This was clearly exemplified during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when digitalization became a key factor to provide people with ongoing access to health services, while minimizing potential exposure to infection. The need for phone connectivity during the pandemic created innovative initiatives in overcoming challenges of accessibility among vulnerable groups in society. One example is healthcare intervention, where individuals were prescribed a phone to improve their access to healthcare, social services, and information, as well as to improve their ability to adhere to public health directives during the pandemic (Kazevman et al., Citation2021). Thus, when striving to solve structural problems, suitable solutions should be constructed and presented on a structural and societal level, instead of delegated to individuals living in dire circumstances (Marmot et al., Citation2012).

Looking closer from a system perspective (Norgaard et al., Citation2015), the two prerequisites for e-Health literacy are: access to digital services that work and digital services that meet needs. Women in homelessness present with multiple, complex needs, with significant overlap between healthcare needs (physical, mental health, etc.) and social needs (housing, financial aid, etc.) (Cush et al., Citation2020; Kneck et al., Citation2021), and successfully translating these complex needs to digital services is a delicate problem. Not only does this require coordination and collaboration between different service sectors, i.e. healthcare, social services, and housing, meeting complex needs require focusing on the bigger picture and implementing holistic solutions to counter fragmented care. Focusing on processes of inclusion, rather than focusing on characteristics of individual groups, may be a way forward to resolve structural digital health inequities. As a means towards this end, co-production with people who have experience of homelessness is essential to ensure acceptability, usability, and relevance of such initiatives (Heaslip et al., Citation2021; Lindhult & Axelsson, Citation2021; Polillo et al., Citation2021).

From digital exclusion to digital inclusion

The progression towards digitizing in social services and healthcare has been notable, heralding enhanced efficiency, accessibility, and service quality (Maier et al., Citation2021). Yet, even with all this excitement about digital technology, an important but often overlooked problem remains – the risk of digital exclusion (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2023). In agreement with our findings, the risk is especially severe for people experiencing vulnerabilities, such as women facing homelessness. Even in highly digitalized nations like Sweden, where indices from the World Bank (Chandrasekhar, Citation2017) suggest extensive digital integration, closer examination discloses a contrasting scenario (Holmberg et al., Citation2022; Holmes & Burgess, Citation2022). Digital adoption is not synonymous with digital inclusion. High ratings on the World Bank’s digital adoption index suggest broad access to and usage of digital technologies at a macro scale, which includes the population, governance, and commerce sectors. Yet, these statistics obscure the individual and collective experiences of people experiencing vulnerabilities, often found in the margins of the digital transformation. The hurdles of digital exclusion go beyond mere access to technology; they also involve complexities concerning digital literacy, affordability, and the relevance of digital content to their particular circumstances (Buchert et al., Citation2023; Safarov, Citation2021). Therefore, we posit that the impact of this ‘digi-social’ exclusion is significant in societies where public services and healthcare are increasingly conducted through digital services.

Our findings indicate that women experiencing homelessness, already experiencing marginalization, face threats to their well-being and survival due to digital exclusion. This situation showcases the paradox of digitalization: while technology is suggested to close gaps and foster inclusion, its deployment may inadvertently exacerbate existing inequalities, pushing the most vulnerable further to the periphery (Osarenkhoe & Fjellström, Citation2021). The critical nature of this issue cannot be overstated for policymakers, health- and social-care services. We advocate for a brand of digital inclusion that goes beyond mere access, embracing a comprehensive approach to counter the multiple barriers to digital engagement for women experiencing homelessness. This approach necessitates creating digital services that are accessible, intuitive, and customized to address the varied needs of all citizens, particularly those experiencing vulnerabilities who are susceptible to exclusion. Furthermore, synchronizing digital initiatives with the SDGs calls for a persistent dedication to fairness and inclusivity. It accentuates the demand for inclusive digital policies and practices, ensuring no one is sidelined in the digital era, especially as we aim for the attainment of universal health coverage, quality education, and gender equality (UnitedNations, 2018).

Several initiatives can aid individuals in overcoming digital exclusion, such as support hubs. These hubs, as expounded by Price et al. (Citation2021), serve as communal spaces providing high-speed internet and services catering to both community and business needs. These hubs have emerged as instrumental in countering the digital divide by offering spaces equipped with necessary technology, fostering digital skills, and enhancing community engagement in rural areas. The establishment of such hubs could be a pivotal step toward mitigating digital exclusion among vulnerable populations, ensuring that digitalization’s promise of inclusivity is fulfilled. Similar centers have been reported to support older Russian-speaking migrants in Finland (Buchert et al., Citation2023), or public libraries’ crucial role in fostering democratic and inclusive societies by providing access and support for digital services. We call for similar initiatives to empower women experiencing homelessness to ensure their full inclusion in our increasingly digital world.

Conclusions

For women experiencing homelessness in this study, use of digital technology, such as mobile phones and internet, comprised challenges with finding internet connection, charging the devices, the risk of being robbed, and technical constraints. Women also described structural problems with accessing digital technology and digital services. To promote health equity and digital inclusion in future implementation of digital services, highlighting and addressing structural barriers as well as acknowledging shifting circumstances among service users are crucial. It is time that the digital divide is systematically addressed and remedied, instead of placing responsibility for access on individuals. Establishing support hubs with services for digital inclusion is one example of a solution to bridge the digital exclusion.

In closing, to accomplish digital inclusion, we believe that principles of co-production and participation must be embraced and involving partners, such as women experiencing homelessness, throughout the implementation process is imperative (Lindhult & Axelsson, Citation2021). Involving the intended users is the only way to create digital services that are accessible and meet complex needs, for example, women experiencing vulnerabilities, one of the most underserved and underrepresented groups in society.

Methodological considerations

The interviews with women experiencing homelessness entailed meeting a heterogenous group with multiple healthcare needs. Substance use, mental health illness, and neurodevelopmental disorders are factors that may have contributed to relatively short interviews (range 9–34 minutes). Thus, the brief interviews gave limited time to engage in sharing life narratives. However, the women candidly described their experiences of using mobile phones and internet when seeking healthcare, sometimes going straight to personal accounts, openly sharing examples of situations regarding highly sensitive issues. We found that the 26 interviews generated rich and varied data, in part due to the immediate openness with personal narratives. The level of potential diversity depends on participating healthcare organizations associated with women who utilize the services. To promote reliability and trustworthiness of the results, we carefully adhered to a systematic approach throughout the research process and possibilities of an audit trail during analyses, using NVivo software.

We acknowledge that the context of women experiencing homelessness in a larger city in Sweden may not fully represent the experiences of women in smaller cities. While our study exclusively interviewed women, it’s important to recognize that the perspectives captured may not encompass the entirety of women’s experiences in homelessness. However, our findings complement existing literature with similar insights. Additionally, this study amplifies the voices of women experiencing homelessness, an underserved and marginalized group. Based on our results and previous research, we believe that our findings are applicable to global settings with similar circumstances.

Author contributions

AK, EM, and MSE provided study conception and design. AK and EM were involved in gaining ethical approval, recruiting patients and performed the interviews. AK, EM, JV, ÅK, and MSE were involved in the data analysis. AK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved this study [no 2019-02143].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the women who shared their experiences in the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [AK]. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldridge, R. W., Story, A., Hwang, S. W., Nordentoft, M., Luchenski, S. A., Hartwell, G., Tweed, E. J., Lewer, D., Vittal Katikireddi, S., & Hayward, A. C. (2018). Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 391(10117), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bretherton, J. (2020). Women’s experiences of homelessness: A longitudinal study. Social Policy & Society, 19(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746419000423

- Buccieri, K., Oudshoorn, A., Schiff, J. W., Pauly, B., Schiff, R., & Gaetz, S. (2020). Quality of life and mental well-being: A gendered analysis of persons experiencing homelessness in Canada. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(8), 1496–1503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00596-6

- Buchert, U., Kemppainen, L., Olakivi, A., Wrede, S., & Kouvonen, A. (2023). Is digitalisation of public health and social welfare services reinforcing social exclusion? The case of Russian-speaking older migrants in Finland. Critical Social Policy, 43(3), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183221105035

- Calvo, F., Carbonell, X., & Johnsen, S. (2019). Information and communication technologies, e-Health and homelessness: A bibliometric review. Cogent Psychology, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1631583

- Chambers, C., Chiu, S., Scott, A. N., Tolomiczenko, G., Redelmeier, D. A., Levinson, W., & Hwang, S. W. (2014). Factors associated with poor mental health status among homeless women with and without dependent children. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(5), 553–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9605-7

- Chandrasekhar, C. P. (2017). World development report 2016: Digital dividends. Development and Change, 48(5), 1196–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12333

- Crawford, T., & Candlin, S. (2013). Investigating the language needs of culturally and linguistically diverse nursing students to assist their completion of the bachelor of nursing programme to become safe and effective practitioners. Nurse Education Today, 33(8), 796–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.03.005

- Cuesta, M., German Millberg, L., Karlsson, S., & Arvidsson, S. (2020). Welfare technology, ethics and well-being a qualitative study about the implementation of welfare technology within areas of social services in a Swedish municipality. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(sup1), 1835138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1835138

- Cush, P., Walsh, K., Carroll, B., O’Donovan, D., Keogh, S., Scharf, T., MacFarlane, A., & O’Shea, E. (2020). Positive health among older traveller and older homeless adults: A scoping review of life-course and structural determinants. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(6), 1961–1978. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13060

- De Rosa, E. (2017). Social innovation and ICT in social services: European experiences compared. Innovation-The European Journal of Social Science Research, 30(4), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2017.1348936

- de Vet, R., Beijersbergen, M. D., Lako, D. A. M., van Hemert, A. M., Herman, D. B., & Wolf, J. R. L. M. (2019). Differences between homeless women and men before and after the transition from shelter to community living: A longitudinal analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12752

- Digitaliseringsrådet (2019). Why a Swedish National Digitalisation Council? Retrieved December 9, from https://digitaliseringsradet.se/om-webbplatsen/english/

- Eyrich-Garg, K. M. (2010). Mobile phone technology: A new paradigm for the prevention, treatment, and research of the non-sheltered “Street” homeless? Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 87(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9456-2

- Eyrich-Garg, K. M. (2011). Sheltered in cyberspace? Computer use among the unsheltered ‘street’ homeless. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.007

- Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet, 384(9953), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- FEANTSA. (2023). Working together to end homelessness in Europe. European federation of National organisations working with the homeless. Retrieved September 8, from https://www.feantsa.org/en/about-us/faq

- Fraser, H. (2004). Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work, 3(2), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325004043383

- Grammatikopoulou, M. G., Gkiouras, K., Pepa, A., Persynaki, A., Taousani, E., Milapidou, M., Smyrnakis, E., & Goulis, D. G. (2021). Health status of women affected by homelessness: A cluster of in concreto human rights violations and a time for action. Maturitas, 154, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.09.007

- Hansen, H.-T., Lundberg, K., & Syltevik, L. J. (2018). Digitalization, street-level bureaucracy and welfare users’ experiences. Social Policy & Administration, 52(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12283

- Heaslip, V., Richer, S., Simkhada, B., Dogan, H., & Green, S. (2021). Use of technology to promote health and wellbeing of people who are homeless: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6845.

- Holmberg, C., Gremyr, A., Karlsson, V., & Asztély, K. (2022). Digitally excluded in a highly digitalized country: An investigation of Swedish outpatients with psychotic disorders and functional impairments. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 36(3), 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2022.04.005

- Holmes, H., & Burgess, G. (2022). Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online. Digital Geography and Society, 3, 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diggeo.2022.100041

- Jiménez-Lérida, C., Herrera-Espiñeira, C., Granados, R., & Martín-Salvador, A. (2023). Attending to the mental health of people who are homeless by mobile telephone follow-up: A systematic review. Healthcare, 11(12), 1666.

- Kazevman, G., Mercado, M., Hulme, J., & Somers, A. (2021). Prescribing phones to address health equity needs in the COVID-19 era: The PHONE-CONNECT program. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e23914. https://doi.org/10.2196/23914

- Kneck, Å., Mattsson, E., Salzmann-Erikson, M., & Klarare, A. (2021). “Stripped of dignity” – women in homelessness and their perspectives of healthcare services: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 103974, 103974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103974

- Leonardsen, A. C. L., Hardeland, C., Helgesen, A. K., & Grondahl, V. A. (2020). Patient experiences with technology enabled care across healthcare settings- a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05633-4

- Lindhult, E., & Axelsson, K. (2021). The logic and integration of coproductive research approaches. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 14(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/Ijmpb-07-2020-0215

- Maier, E., Reimer, U., & Wickramasinghe, N. (2021). Digital healthcare services. Electronic Markets, 31(4), 743–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-021-00513-z

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Bell, R., Bloomer, E., Goldblatt, P., Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of, H., & the Health, D. (2012). WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet, 380(9846), 1011–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8

- Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class. Cambridge University Press.

- McNaughton, C. (2008). Homelessness, identity and social networks. In C. McNaughton (Ed.), Transitions through homelessness: Lives on the edge (pp. 139–167). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230227347_7.

- Neale, J., & Brown, C. (2016). “We are always in some form of contact’: Friendships among homeless drug and alcohol users living in hostels. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(5), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12215

- Norgaard, O., Furstrand, D., Klokker, L., Karnoe, A., Batterham, R., Kayser, L., & Osborne, R. H. (2015). The e-Health literacy framework: A conceptual framework for characterizing e-Health users and their interaction with e-Health systems. Knowledge Management and E-Learning, 7(4), 522–540. https://doaj.org/article/4eb68853becc40e9ab209f0e1f4acf45

- Osarenkhoe, A., & Fjellström, D. (2021). The Oxymoron of digitalization: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Information Technology Research, 14(4), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.4018/JITR.20211001.oa1

- Polillo, A., Gran-Ruaz, S., Sylvestre, J., & Kerman, N. (2021). The use of eHealth interventions among persons experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. Digit Health, 7, 2055207620987066. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207620987066

- Price, B. (2002). Laddered questions and qualitative data research interviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02086.x

- Price, L., Deville, J., & Ashmore, F. (2021). A guide to developing a rural digital hub. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 36(7–8), 683–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942221077575

- Safarov, N. (2021). Personal experiences of digital public services access and use: Older migrants’ digital choices. Technology in Society, 66, 101627.

- Salzmann-Erikson, M. (2023). Digital inclusion: A mixed-method study of user behavior and content on Twitter. Digital Health, 9.

- Schou, J., & Pors, A. S. (2019). Digital by default? A qualitative study of exclusion in digitalised welfare. Social Policy & Administration, 53(3), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12470 [Record #9080 is using a reference type undefined in this output style.

- United Nations. (2018). Agenda and the sustainable development goals: An opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean (LC/G. 2681-P/Rev. 3).

- Vazquez, J. J., Panadero, S., Martin, R., & Diaz-Pescador, M. D. (2015). Access to new information and communication technologies among homeless people in Madrid (Spain). Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21682

- VonHoltz, L. A. H., Frasso, R., Golinkoff, J. M., Lozano, A. J., Hanlon, A., & Dowshen, N. (2018). Internet and social media access among youth experiencing homelessness: Mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(5), e184. [Record #11207 is using a reference type undefined in this output style.

- Williams, H., Faith, B., & Waldman, L. (2023). Technologies of inclusion and marginalization: Mobile phones and multiple exclusion homeless women. Mobile Media & Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579231211498

- World Health Organization. (2018). eHealth at WHO. Retrieved December 9, from https://www.who.int/ehealth/about/en/

- World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki, 2013 Amendment. Retrieved June 1, from https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/

Appendix

Interview guide

Can you tell me about when you wanted care in … (city)? Why were you seeking healthcare? What happened? What happened next? How did that work for you?

What are your thoughts about healthcare for women in homelessness? What works well? What doesn’t work well?

If you could design healthcare for women in homelessness, what would that look like? How do you think care should be designed to better care for women in homelessness? Can you please tell me more? Do you have any suggestions for improvements?

Do you use a mobile phone or internet? What possibilities and challenges do you see with using mobile phones and internet to seek healthcare?

Is there anything you would like to add that would be important for us to know about healthcare for women in homelessness? Do you have any questions for us?