ABSTRACT

Physical touch is considered a core competency in Physiotherapy, central to clinical reasoning and communication. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of research into how the skill is learned and the experiences of students in that process. The aim of this paper is to explore that learning experience among pre-registration physiotherapy students. An approach underpinned by phenomenology and ethnographic methods was undertaken over an 8-month period in one Higher Education Institution in the UK. Data came from a series of observations and focus groups, complemented by personal reflective learning diaries with first- and second-year undergraduate students. Focus group data were analyzed thematically and triangulated with other data sources. Three themes were developed: 1) ‘Uncertainty, self-awareness and anxiety’ explores the discomfort experienced in the early stages; 2) ‘Emerging familiarity and awareness of inter-action’ demonstrates developing confidence in bodily capability and communicative capacity; and 3) ‘Realities of touch in a clinical environment’ focuses on the shift from the pre-clinical to clinical context and highlights the cyclical processes of embodied learning. This study highlights the complexity and immediacy of the embodied learning of touch and its interactions with the development of professional identity. Negotiation of boundaries, both seen and unseen, creates jeopardy in that process through the first two years of the course.

Background

Physical touch, the connection of one body with another, is considered a foundational element of physiotherapy practice and a core competency (Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel, Citation2016; Doran and Setchell, Citation2018; Kordahl and Fougner, Citation2017; Moffat and Kerry, Citation2018). Touch is used professionally in multiple ways as a: diagnostic tool; therapeutic intervention; assisting individuals in movement; and in communication (Roger et al., Citation2002). As a consequence, physiotherapy has been described as being performed in a high touch arena (Owen, Citation2014; Roger et al., Citation2002; Thornquist, Citation2006) where the elimination of space between patient and practitioner is pervasive (Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel, Citation2016) demonstrating the perceived centrality of touch to the profession. Touch has a long association with the profession, pre-dating the development of the term physiotherapy itself which other authors have documented in detail (Nicholls and Cheek, Citation2006; Nicholls and Gibson, Citation2010). Despite this long history and apparent importance of touch, research in the field of physiotherapy is limited leaving significant gaps in our understanding of its role, use and, critically, how it is taught.

Research completed to date does give us some insight. Within the world of healthcare, including physiotherapy, touch has been re-labeled and categorized in multiple ways. Several different forms of touch have been observed and named in physiotherapy practice, serving multiple purposes, including assistive, preparatory, for intervention, building rapport, perceiving information and security (Roger et al., Citation2002). The word touch itself is often avoided in practice, replaced with terms such as palpation, massage, mobilization, manipulation, and facilitation (Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel, Citation2016; Moffat and Kerry, Citation2018). These terms most commonly fit the description of therapeutic touch (Paterson, Citation2007), denoting the professional laying-on of hands for a specific and therapeutic purpose.

Touch within physiotherapy has also been considered as central to clinical reasoning (Gardner and Williams, Citation2015; Oberg, Normann, and Gallagher, Citation2015; Owen, Citation2014; Rose, Citation1999). Through this, it is conceptualized as a tool that, with skillful application, can assist in uncovering and revealing both the problem to be addressed and potentially the mechanism for redress (Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel, Citation2016; Normann, Citation2018). Oberg, Normann, and Gallagher (Citation2015) argued that for this to occur, therapists must engage in a phenomenological conceptualization of the body as the physical means of action (body-as-object), simultaneously with being an experiencing and expressing body (body-as-subject). They also suggested that both the practitioner and patient are active and enactive embodied partners in this process, so ownership of the content, direction, and experience of the session is shared by both parties. Embodiment in this context refers to an understanding of the body as physical and affective, intersubjective and situated, the means whereby we both experience and create self and the world around us (Elllingson, Citation2017; Gallagher, Citation2013). This emphasizes the need to not only understand how therapists learn the control of their body in order to be skillful but also the sense of their body in time and place within a specific interaction with another embodied individual.

Some writers on touch within the profession have indicated that the skilled use of touch is developed from experience not training (Roger et al., Citation2002). Such views are based on research completed with experienced practitioners and does not fully capture the learning that occurs at the formative stages of training. The very limited insights there are to the learning of professional touch prior to professional registration have largely focused on clinical placements. Covington and Barcinas (Citation2017) explored the learning of movement during placement from the perspective of both students and clinical educators. A focus on how students learned movement dominated, but there were also examples where touch was referred to. For example, the hand-over-hand method was described as the most effective guide to learning.

To our knowledge, there is only one study that has explored touch within the pre-clinical stages of physiotherapy education and this focused on the learning of a specific manual technique which is not universally taught (Kordahl and Fougner, Citation2017). First-year students involved in this study reported initial discomfort at being the subject of touch and its related state of undress, as well as being the deliverer of the touch. While that initial apprehension was replaced by confidence and comfort, students appreciated the insight gleaned from being the active and embodied recipient, enhancing their bodily empathy (Rudebeck, Citation2001). Likewise, reflecting on their experiences demonstrated an appreciation of the intersubjective nature of touch, the communicative potential that needs to be nurtured and carefully established, particularly with students previously unknown to them. Students also referred to certain manual skills and specifically the force required for them in gendered terms and illustrated a different engagement with the skill as a consequence. Likewise, the boundaries associated with touch were also gendered, indicating a sensibility to different concepts of intimacy. Such findings are in line with previous studies (Dahl-Michelson and Solbraekke, Citation2014; Hammond, Citation2009) and highlight the need to remain vigilant to the interplay between social expectations of bodily interaction and professional touch. Kelly et al. (Citation2018) highlighted a need to better understand how touch is taught and learned by Health Care Professionals. The aim of the study was to expand on this limited literature by responding to the research question: How do pre-registration physiotherapy students within a UK context experience the process of learning professional touch?

Methodology

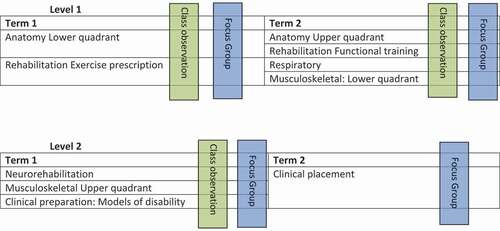

This was a descriptive qualitative study based in one Higher Education Institute in the South East of the UK. Ethical permission was granted for the study by Brunel University London’s College of Business, Arts and Social Sciences (REC reference 3742-MHR-Sep/2016- 4072-1) in which one of the researchers was located. Various forms of data collection across an eight-month period in the academic year 2016–2017 were utilized in the study. These included observations of university-based tutorial classes for one group in each year in which students were being taught manual skills, and therefore learning of professional touch was likely to be a relevant component. The relevant classes included anatomy, rehabilitation, musculoskeletal lower limb and respiratory for first-year students and musculoskeletal upper limb for second-year students. All classes occurred prior to exposure to clinical placement. The classes typically involved 20 students with one tutor and were conducted in skills specific classrooms. Each had a different format but demonstrations on an individual followed by paired working (i.e., student and model) which were rotated frequently, was a common pattern. In total 14 hours of classes (7 classes of 2 hours) were observed. A total of 40 students were observed in class (21 1st year/19 2nd year). Field notes based on the observations were taken in situ noting activities and student responses, both verbal and physical. These were prompted by an observation guide developed by the researchers and which focused loosely on the themes of the physical environment, chronology, and structure of the session, relations within the class, and teaching content and process. Observation, recorded through field notes, was selected for its capacity to see the learning in action and the students’ responses in a naturalistic setting (Toren, Citation1996).

Focus groups, involving volunteers from the observed classes, were conducted for the students to discuss their experiences of bodywork over the preceding period of learning. They were selected over individual interviews because of their explicit use of group interaction in data creation (Flick, Citation2014). Furthermore, the learning of touch had occurred in specific groups and focus groups are noted to enhance interaction particularly in previously formed groups (Kitzinger, Citation1994). All focus groups were audio-recorded. A topic guide () directed the focus groups which was developed to be flexible to the specific areas and stage of study (e.g., the final focus group specifically focused on bodywork in clinical placement).

Table 1. Focus group broad topic themes

The researcher who facilitated the focus groups had undertaken the observations and so also encouraged the students to reflect on specific observations made in the classroom. In total five focus groups, each of two-hours duration, were conducted across two points in the academic year and learning trajectory. In total 11 students (eight 1st years and three 2nd years five males and six females) took part in the focus groups.

Finally, students who volunteered for the focus groups were also invited to keep personal diaries of their experiences within the classroom and beyond in relation to bodywork more generally. The purpose of these diaries was to try to capture the evolution of their experiences over time rather than the retrospective nature of the focus groups (Bowling, Citation1997). Brief guidelines were given including date, subject, and comments on reflected experience. These diaries were completed anonymously and submitted to the researcher responsible for data collection at the end of the study period; however, they were poorly completed with only seven participants returning them, many with very limited entries. While it is acknowledged that diary completion and participation in focus groups may act as active learning tools for the students, focus here is given to their primary role as data collection methods for the purposes of research. illustrates the timeline of the different data collection methods.

The observations and focus groups were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher who has previously explored bodywork, external to the physiotherapy department and who herself was not a physiotherapist. Her independence from the physiotherapy course was considered important for the ethical conduct of the study. Prior to the data collection, she had read the program and module outlines to familiarize herself with the aims of the sessions and the skill set required through the teaching. These were not templates from which the classes would be judged but rather an opportunity for the researcher to familiarize herself with the language and indicative content which was previously unfamiliar.

All students attending the classes were informed of the purpose of the research and that observation would be conducted and the purposes of the researcher’s presence. In line with ethical guidance whole class consent was required and all students agreed to be observed. A convenience sample of volunteers from the observed groups gave further informed consent for involvement in the focus groups and diary completion. All were aware that the data collection would be conducted by a non-physiotherapy staff member and while a member of the faculty was involved in the analysis, all data would be anonymized prior to her involvement to ensure confidentiality was not breached.

All focus groups were audio recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. They were further checked against the recordings and individual voices were identified in the transcripts. The transcripts and diaries were anonymized prior to analysis. Inductive thematic analysis was conducted by the primary author who is a member of the physiotherapy faculty. It involved six stages as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Initially, the transcriptions were read several times in order to aid familiarization with the data. This was particularly important as the primary analyst had not conducted the focus groups. This was followed by detailed manual line coding of any sections of the transcriptions in which touch was a topic of discussion. Memos were made to note any specific points of interest. Codes were transferred onto post-it notes and the process of thematic development initiated. This initial phase only utilized data from the focus groups and critical discussion with the co-researcher who had conducted the data collection was initiated to refine and challenge the developing themes (Shaw, Citation2010). Once completed the preliminary themes and sub-themes were reviewed alongside observational notes and diary entries. These acted as a form of triangulation to either support or challenge the development of the preliminary themes. Further critical discussion with the co-researcher occurred at this stage and agreement on the themes reached. Following this process, the final themes were reviewed against the dataset and memos to ensure appropriate coverage. Supporting quotes were selected and were read in situ of their transcript to reassure meaning had been appropriately captured.

The use of critical dialogue in the development of the themes was deemed essential because the primary analyzer is herself a physiotherapy lecturer and did not conduct the data collection. As a result, there was both a need to clarify situational insights and also check on potential professional influences throughout the analytical process, thereby acting as a form of reflexive space (Finlay and Gough, Citation2003).

Findings

Three sets of themes were developed from the data. First, ‘uncertainty, self-awareness and anxiety’ explores the early stages of learning and mostly draws from the first-year data. Second, ‘emerging familiarity and awareness of inter-action’ sequentially follows this. The third and final theme ‘realities of touch in the clinical environment’ focuses on the shift from the pre-clinical to clinical context and highlights the cyclical processes of embodied learning. Emerging professionalism runs through these sets of themes.

In quotes that follow, the identity of the speaker is noted with reference to year of study, focus group number, and gender, e.g., 1:FG2:M referring to 1st year, focus group 2, male. Observation and diary notes are referred to in relation to the year of study.

Uncertainty, self-awareness, and anxiety

The very act of touching another person was initially met with apprehension and awkwardness. For younger participants, the task was seen as both novel but also breaking with previously learned implicit and explicit school and workplace rules which excluded touch. For others, who had already been exposed to learning anatomy, the use of living bodies as opposed to models and cadavers created unexpected concerns. The result was a mix of anxieties ranging from their control of self, breaching an unspoken line and performing in a public arena.

At the initial stages of the course, different aspects of their own personal body control were a preoccupation. This was in part a concern with making errors in what was a novel task.

For me it was just like touching someone else … The first person, we had to like just do flexion, like just flex someone’s arm and because I’d never done that to someone before, I don’t know, I was nervous doing it in case I’d do it wrong. So even just touching someone in the beginning, I was like really nervous about. 1:FG2:M

This nervousness with initiating touch-related tasks was noted in field observations, most especially in relation to the move from students probing their own bodies, to moving onto those of their peer group. Tentative hesitant movements, coupled with cautious and uncertain language, marked these first encounters with others.

In exploring why students were concerned about mistakes, they focused on their inability to understand what their hands were feeling.

There is probably some precision trick but because we haven’t quite got the sensitivity and experience in our fingers for example … 1:FG1:F

This lack of nuanced physical control was emphasized by the use of language in the early focus groups, where the word poke was frequently used.

The participants also described becoming hyperaware of how their body functioned, particularly the parts that were coming in contact with another.

I worry about my hands, having too sweaty hands, or cold hands as well. 1:FG1:F

There was a further focus on being physically acceptable both in relation to being the student and the one who was being touched. Anxieties over ticklishness and subsequent inability to be a ‘good’ model to be the appropriately presented and behaved model were observed and reflected on in focus groups. Field notes highlighted feet as points of anxiety; as parts of the body normally hidden and rarely drawn attention to, their presentation to others was joked about in terms of smell, roughness, and sense of deficiency. In addition, having hairy legs, being sweaty, showing evidence of not showering, through, for example, remaining pen marks, were all mentioned as concerns. Field notes and diaries suggest a further concern with having an adequate body for the task, with muscles suitably formed, slim enough for bones to be felt.

But control of self was not limited to physical attributes, but intricately linked with the confidence in which you presented yourselves during the task.

I think also it’s the person who is doing the like poking stuff, you’ve got to like, it’s back to the confidence thing because if you are like a bit awkward around it, that’s going to make them awkward too. Whereas if you are like I know what I am doing then it is fine. 1:FG1:F

Here the participants added to the physical presence with emphasis on clarity in the words they used and directness in their touch, which collectively demonstrated competence in the task. The act of touching another required surveillance of their entire person of self and other.

For many of the students, concern with their lack of skill and acceptable presentation centered around a sense of jeopardy in the activities related to touch. This was created by a series of unspoken but widely understood lines of acceptability. One was the social acceptability of personal space, the line between public and private space:

Just being a bit like, I don’t know invading your personal space. You know there’s such a fine line in what we are doing and there was uncomfortableness in the group at the beginning. 1:FG1:F

The reference to a fine line hints at the negotiation students perceived they had to manage. It is also apparent in the above quote that this negotiation was shared within the group, and the lack of collective skill in the early stage of learning created a layer of social jeopardy.

A further concern was created by the sense that breaching the line could cause harm, discomfort, or pain, exactly the opposite effect of their intention.

Yes, he (tutor) just goes on, like he knows exactly what he’s going for, he knows exactly how to do it but I feel like when I do it, even now, I struggle where to put my hands and stuff. I worry if I am pushing too hard, if I am going to hurt someone. It’s always in the back of your mind but obviously I feel a lot more comfortable now than doing it at the beginning, but even still I still worry. 1:FG1:F

Students were aware that their lack of skill ran the risk of inadvertently going beyond acceptability. This was heightened by instructions of care, points of sensitivity and potential risk stated by the tutor as observed throughout the tutorial sessions, whether in relation to body-to-body touch, movement, and instruction.

Fields notes illustrate that modeling partners were encouraged to give continuous verbal feedback to assist in this task, indicating when the hands were misplaced or suggesting altered pressures, in an explicit acknowledgment that this was a skill in process. Participants in the focus group suggested that the familiarity within the group quickly established a trust that your peers would give such feedback. While the quote above suggests such feedback mechanisms and practice improved the sense of comfort, if not skill, there was still progress to be made at this early stage of training.

While pain was one concern, another was breaching the line sufficiently to enter intimate space, something that was considered so taboo that discussion and acknowledgment were rarely possible.

Tom, do you know in practicing, Tom did it, and he touched the wrong place. [group laughter]

And what do you do, I mean, what do you do in that situation?

Pretend it doesn’t happen pretend it doesn’t happen

I didn’t say anything.

They know what happened …

But a few weeks later, I saw him and he was drunk. I was like, ‘you know you touched my thing’, but, and he was like, ‘yes, I know’. He was being honest because he was drunk that night, yes, it was.

Yes, clearly didn’t want to talk about it. 1:FG2

This extended interaction highlights not only the inherent danger of the activity but also that the feedback mechanism of partner conversations noted previously as essential, has limitations in the realms of intimate and sexualized space.

Nevertheless this was a sanctioned breach, that of palpating the pubic tubercle, which were considered intimate but also the target of their activity. Participants discussed that in this task “we didn’t cross that barrier, we smacked right through it” (1:FG1:M) which left them all feeling very awkward. However, having completed it everything else seemed ‘tame’ in comparison and consequently the location of the line was redrawn.

Part of the challenge identified by the participants is that this process of learning touch was occurring in a public arena.

There were some people in the room perhaps that sort of struggled with being part of the group and perhaps some of us felt a bit awkward as a result at the beginning, it is all fine now but it was a bit of awkwardness at the beginning. 1:FG2:F

As noted in this quote, time and familiarity resolved some of this concern. Critically though this was within the confines of a specific group. Students who had to swap to other groups for various reasons noted that they were “thrown back to the beginning” (1:FG2:M), once again feeling very self-conscious in the group of basic strangers.

Equally, the level of comfort depended on the area of the body being worked on. Having negotiated the pubic region in this professional but shared space the rest of the lower body was considered as less threatening. Anticipation of working on the upper body in the following term threw up different challenges. Working around the torso, “the lungs and stuff” (1:FG2:F) was considered potentially more invasive and therefore reiterated public bodily concerns which had to be negotiated once again. Perhaps unsurprisingly this concern was articulated by female students who clearly pointed to a need to understand how individuals would feel about such exposure and handling.

Collectively these anxieties, control of self, potential of breaching the line and performing in a social space, while broad in nature share a common focal point; that of professionalism. This novel and, in some respects, potentially dangerous use of touch had been sanctioned because this was a professional arena. But the students struggled with the demands of professionalism, alongside the very early learning stages of the skill.

Knowing how to sort of be, we are not professionals but we still have to be professional don’t we, with what we are doing. 1:FG2:F

Consequently, there was a perceived expectation of a further level of skill, that of a specific behavior which they had to learn almost instantly.

Emerging familiarity and awareness of inter-action

In time, the strangeness and potential jeopardy related to touch in the classroom setting eased. Even at the end of the first 12 weeks, a sense that it was becoming “just like second nature” (1:FG1:F) was evident, suggesting participants quickly appropriate the skills of touch, moving away from an overlying concern with their own delivery to an embodied familiarity. This gave room for more exploration of the nuances of touch and through that, capacity to utilize the breadth of opportunity touch can create.

By the end of term two of the first year, this familiarization with the processes of professional touch accompanied a heightened awareness of bodily skills and sensitivity. Students talked about consciously trying to “be less pokey” (1:FG2:M) by using their hands rather than their fingers, “holding more firmly” (1:FG2:F), and not handling “half-heartedly” (1:FG2:M). Alongside, participants became more comfortable with exploring through touch, problem solving and developing their skills through doing:

I think it’s that not being afraid to move somewhere around and then, and use that to work out what you’re meant to be doing, rather than sort of just, sort of slightly touching, and not really sure what to do. I think that’s what actually using it as like a learning tool, that helps, and so yes, so not going in sort of all shy with it. Just go, ‘Okay so I don’t know exactly what I’m doing, but I’ll move around, and okay, that makes sense. We’ll do it like that.’ So, yes, it’s just sort of teaching yourself how to, how’s the best way to go about it, I think really. 1:FG2:F

Notable in this exploration is the absence of concern of crossing lines of acceptability; a distinct shift from the previous preoccupation. At this stage, not yet one year into the course, the participants were focused more on understanding touch and the sense of jeopardy has diminished. Linked with this was a move away from needing feedback from models to their own intrinsic sensitivities.

Linguistically there was also a significant change. Poke, so ubiquitous at the start, was replaced with palpation. This professionalized term indicates a shift in apparent skill and professional presentation of the activity. Indeed, by the second year of study, the word poke does not appear at all and reference to touch is infrequent. Rather manual handling, manipulation, distinguishing high tone, and doing PA’s (i.e., posterior-anterior mobilizations) become the new highly professionalized descriptors of touch. Participants used these terms consistently with no explanation, they were a known and shared language.

As comfort with their own body use developed, participants focused more on the interaction with the other. Touch in this sense was less about what they were feeling under their hands but what their hands were communicating to the model. This was explicitly linked with the transmission of confidence; hands that were calm, appropriately positioned and placed without hesitancy. For the participants in this study communicating and instilling confidence was an essential part of the efficacy of touch.

Yes, and just like especially with manipulations, when you know where you have to be, it makes it easier. So if you have to, let’s say like working on someone’s neck and then you get in the right position, like behind them and you are secure, and you are holding everything properly, it is a smooth thing. Whereas if your handling is wrong, then you have to move about a bit and readjust and then they are sitting there like what are they doing? They are moving about, they don’t know what they are doing … . But the fumbling about makes it feel like you are not sure of your task. Whereas if you immediately just go in, handling right, doing this, that’s fine then it shows that you kind of know what you are doing and there’s confidence in you. 2:FG1:F

Participants talked about laying hands on to complete specific techniques, while at the same time having contact through touch to reassure. This was specifically noted when models were face down and techniques only required one hand.

[I]f treatments are using one hand, say you are doing a PA on the back, or doing like your palm, you should keep your other hand on the patient. So that they know where your other hand is. Otherwise it could be anywhere. 2:FG1:M

Here, the second point of touch was one of assurance and clarity, once again reflecting the sense that these practices could be considered socially ambiguous. Such clarity was also delivered through verbal mechanisms. Models were ‘warned’ that they were going to be touched, a verbal signaling that something potentially unusual was about to occur. These secondary communicative processes were closely aligned with professionalism, trust, and rapport. Signaling action, clarity in that action and the removal of ambiguity were seen to be hallmarks of a professional. This then facilitated the trust and understanding that led to appropriate treatment.

Realities of touch in a clinical environment

The onset of placement resulted in a range of opportunities but also different threats to the participants in relation to touch. As demonstrated in the extended interaction below, the language of concern and fear is reminiscent of the initial exposure in the first year of study.

Then it is also kind of shocking that you are now an expert. We’ve practiced it and we’ve pretended it but then actually being someone’s expert and what I say goes, and what I think is the problem, that’s what we are going to treat, is just going to be a shock to be like okay I am actually doing this and I know my stuff but I’ve got to show it. Then you are responsible for someone with each other if you mess up. Ow that hurts a bit, don’t pull it that far. With the patient, one they might not tell you and two you can do lasting damage. So it is going to be like …

You have quite a lot of responsibility.

Yes, there’s a lot of like fear I think, but then you know you are going to be watched

but it is still scary because there’s a potential where you can actually do something

wrong. 2:FG2

The suggestion here is that the confidence and skills developed in the preceding 18 months were based on pretense and significant concern was raised that they would be found wanting when facing reality. Following placement, these fears were in part dispelled and the conversations focused more on new learning that had occurred while working with real patients.

One area of considerable focus group discussion was the variety of bodies participants had to work with and, as a consequence, attention was drawn to adjustments the participants (students) had to make in order to touch appropriately. Use of equipment, such as altering bed height to ensure they did not damage themselves while working with their patients, but also to create positions of mechanical advantage in delivering specific techniques were highlighted. But the bigger challenge came with the variety of bodies in one setting. This was particularly noted in pediatrics when participants described going from a neonatal unit when touch was limited, to working with five year olds who can be ‘thrown around a bit more’ 2:FG2:M, to teenagers who were bigger than the participants themselves. As a consequence, when and how they handled varied, and they found the quick adjustments were challenging to implement. More subtle were anticipatory adjustments participants made in response to symptoms or diagnosis:

So, sometimes I could be a bit too gentle when palpating or doing different tests initially, just to try and like gauge like, how much pressure you need to put through someone who’s actually experiencing pain, because obviously with like us lot when we’re practicing, we’re all healthy. We can kind of press generally as hard as you want to, but then if someone’s got like really severe back pain, you don’t want to press too hard.2:FG2:M

Once again the specter of potential damage resulted in a hesitancy and a suggestion that new learning in this real context had to occur. Those who actually had pain were different to those who pretended to have pain and consequently the skills acquired had to be re-tuned. This sentiment was reiterated by participants who had been on neurological placements and were experiencing altered tone for the first time.

In contrast, participants reflected more intensely on the capacity of touch to develop relationships with their patients. While previously this had been predominantly reassurance of safety, now touch was used to communicate care. Participants discussed how passive mobilizations were done on a regular basis despite a lack of evidence of efficacy:

Even though there’s not much evidence to say that the hands on stuff works really well, it just helps to build that rapport and builds their confidence in you which could in turn help them to recover a bit more 2:FG2:M

Such reasoning directly inverts the focus of physical skill acquisition at the start of their training, to more emotive and interpersonal use of touch now in practice.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore how professional touch is learned and experienced in the early stages of physiotherapy education. Main findings include an initial preoccupation with personal body control, breaching lines of intimacy and managing the social space. This developed into a greater concern with and exploration of interaction through touch. The focus on the communicative potential of touch was enhanced further through the onset of placement, but with a concomitant return of fears of inadequate bodily control.

It has highlighted both the centrality of touch in physiotherapy education and practice but also challenges the way in which touch is currently conceived, presented, and taught. The understanding of the lived subjective body that is gleaned through touch was a feature as well as the process of cultivation over the course of time and practice. Likewise, the variety of bodies and hence adaptation of skills was also illustrated. But critically these developmental insights into the embodied nature of touch and physiotherapy were illustrated from the first few weeks of their training, in some cases over a year before they go into the clinical environment, and presented students with significant concerns regarding inadequate skill and potential transgression. Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel (Citation2016) suggested that the creation of bodily dialogue, the combined sense of the physical and living body, is developed through practicing the profession. The data from this study indicate that practicing the profession is an immediate demand, one that requires careful negotiation and possibly reconfiguration. Closer examination of the themes and their specific implications are discussed below.

Linearity and disruptions in learning professional touch

The findings suggest a linear trajectory of learning touch at the early stages of pre-registration training, although there was evidence of disruption and regression immediately prior to placement. Initial learning focused on the control of self. Crude language mirrored crude movements and an overwhelming sense of uncertainty in controlling themselves in all aspects of presentation; physical, verbal, and in touch. This led to some insecurities with enactment of touch which mirrors the work of Kordahl and Fougner (Citation2017), but goes beyond a sense of discomfort, adding a perceived danger in the activity (Nicholls and Holmes, Citation2012). A concern with causing damage and pain was commonly discussed, and there was an acknowledgment that others learning alongside them were also uncomfortable, but levels of concern particularly in relation to intimate and sexualized spaces demonstrated different levels of jeopardy. This was in part influenced by past experience but also the gendered and sexed body. Once again this aligns with the findings from Kordahl and Fougner (Citation2017) and other writers on inappropriateness within therapeutic touch (Kertay and Reviere, Citation1993). Also highlighted was the social taboo of discussing potential transgressions; one challenge here is the sense that understanding and managing the perceived dangers can only be achieved through doing, yet their doing is personally and socially precarious. Another challenge is the irony that is created by this approach to managing jeopardy. On one hand, ‘smacking right through’ normal social barriers may be considered a form of rites de passage of professional socialization. But on the other, it potentially condones an approach at odds with the concerns of individual dignity and negotiated acceptability emphasized and expected later. The narratives from these students and the evident and immediate presence of the embodied nature of learning touch, both for the student and their model, call for a reconsideration on how teaching touch is approached. Rather than a focus on skill learning which is later honed to consider the individual, an initial orientation to the inter-subjective and inevitability of embodiment in touch could act as sensitive and coherent bedrock on which the skills can be applied. Roger et al. (Citation2002, 185) suggested that “didactic education does not adequately explore the use of touch in physiotherapy” and the findings from this study would support that statement and highlight the need for more nuanced approaches.

The professionalization of touch

The precarious nature of learning touch was exacerbated by the sense of behavioral expectation. The students were aware of what professionalism looked like, having seen it modeled by their tutors. However, enacting it themselves proved challenging. In combination, this early stage within the first 12 weeks of training presents as not only a high touch arena but also a high stakes arena.

There was evidence that the initial danger was short-lived and that experiential group learning in the classroom setting facilitated enhanced sensitivity, skill, comfort, and critically confidence in their ability. The development of professionalization of touch was demonstrated by the change in language in line with observations by Bjorbaekmo and Mengshoel (Citation2016) and Moffat and Kerry (Citation2018) and the enhanced capacity to focus on presentation of self in a broader sense. Likewise, the students described a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of touch. Paterson (Citation2007) reminded us that touch is a multi-organ sense; cutaneous sense from the skin, mixes with the tactile sense of pressure, kinesthetic information on bodily movement and proprioception which situates movement in space. These were all aspects considered by the second-year students and further enhanced through exposure to an array of different touch environments on placement.

But while the skills of touch developed, there were some notable absences. One is the lack of discussion of touch as a clinical reasoning tool, emphasized in the previous literature (Gardner and Williams, Citation2015; Oberg, Normann, and Gallagher, Citation2015: Owen, 2015; Rose, Citation1999). This was not raised in any focus group or diary entry. While it is entirely possible that students do include this in their thinking, its absence suggests that it does not predominate at this stage of learning. Another was the limited reference to feelings potentially provoked by touch outside of discomfort and reassurance. Paterson (Citation2007) drew attention to consideration of the interaction between touch and feeling as a somatic sensation. Given the precarious nature of early exposure to touch and focus on the need for professional presentation, it is perhaps unsurprising that detailed exploration of feeling is limited. This observation in part supports Kelly et al. (Citation2018) assertion that body-as-object is a more significant focus in education as compared to body-as-subject, but as previously noted there is evidence in this data to suggest not only a shift in that emphasis may be appropriate but also in the order in which they are introduced. Further exploration during the latter parts of education would be useful to examine if, where and how these two aspects, clinical reasoning through touch and somatic involvement appear as substantial concerns.

Communicative capacity of touch

The communicative role of touch and specifically sharing of empathy has been discussed both philosophically and within practice literature such as nursing (Edwards, Citation1998; Salzmann-Erikson and Erikson, Citation2005). Kordahl and Fougner (Citation2017) described the early learning of communication through touch in physiotherapy students. Kelly et al. (Citation2018) specifically noted the communicative role in physio as being one of the physical support alongside the communicated sense of safety as they, the patient and the therapist, move. Results in our study suggest that while the communicative aspects of touch are appreciated, any focus on them in the very initial stages is somewhat obliterated by the intensity of self-concern. In order to begin to appreciate the other, there first has to be a level of embodied control of self.

With time and practice, reference to communicative roles of touch develop, but its nature somewhat differed from previous descriptions. Focus here was on physically articulating safety, but primarily safety from the physiotherapy student themselves. Giving knowledge of where their hands were was an act of reassurance of appropriateness. With time, other aspects of communicative touch were articulated but again these differ from previous literature. The use of specific therapeutic techniques, such as mobilizations, for the explicit purpose of creating rapport rather than as an efficacious intervention has not previously been fully explored. These descriptions do however align in part with the extended framework of facilitation outlined by Normann (Citation2018). This theory highlights the inter-relationship between the enactment of movement and the meaning of that movement as co-created by two subjective bodies, that of the therapist and patient. The findings presented in this paper would suggest that such a theory could be usefully applied to the learning of touch as well as facilitation in clinical practice.

It is acknowledged that this study presents apparent stages of learning professional touch, rather than fluid and potentially fluctuating transitions. This is likely to be influenced by the data collecting processes and the poor completion of the personal diaries which may have given a more developmental perspective of the learning trajectory.

Kelly et al. (Citation2018) discussed touch as a high stakes interaction in which negotiating boundaries is dynamic, individual, and requires constant reappraisal. The results of this study demonstrate this complex negotiation and the challenges students face at the initial stages of training, findings which potentially challenge how touch is approached in education. But it also highlights that familiarity with this process in one context, that of university classrooms, is not necessarily transferable. Perceived dangers are relived and amplified when students first move into clinical arenas. This results in significant preemptory stress. While trepidation when first touching patients has been discussed previously (Grant, Giddings, and Beale, Citation2005; Tune, Citation2003), this is the first study to trace the ebb and flow of that trepidation.

Implications

The findings of this study highlight a number of considerations in the education of touch. The embodied nature of touch is immediately evident to students and learning strategies to understand and explore inter-subjective interactions should be included from the outset. This would require the students to be introduced to the theoretical framework of understanding the body as the center of experience and expressions (subjectivity) concurrently as a biological organism and biomechanical system. Such an approach would necessitate a shift of emphasis in the curriculum to balance understanding of the subjective body alongside biomedical reductive concepts. Given the critical role of the tutor highlighted in this study, such a change is predicated on tutors awareness and competence in this field.

Learning touch is not only skill based but a complex social encounter. Guidance regarding perceived dangers, management of self and negotiating boundaries should be considered a more explicit educational task and should be reconsidered to more appropriately align with concerns for dignity and individual negotiation. This requires a willingness and ability of educators to engage in appropriate dialogue with students to address concerns and navigate social dynamics.

Preparation for clinical placement should include strategies to anticipate and manage returning anxieties regarding touching different bodies. Clinical educators should be aware of the insecurities that students embody on initial placement and anticipate some potential regression in performance of skill until the new boundaries are understood. Explicitly highlighting this in clinical education training may serve to support students in the transition. Where clinical reasoning through touch and the multiple layers of communication are developed would be a useful area of further enquiry.

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Bjorbaekmo W, Mengshoel A 2016 “A touch of physiotherapy” – The significance and meaning of touch in the practice of physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 32: 10–19.

- Bowling A 1997 Research Methods in Health. Investigating Health and Health Services. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Braun V, Clarke C 2006 Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101.

- Covington K, Barcinas S 2017 Situational analysis of physical therapist clinical instructors’ facilitation of students’ emerging embodiment of movement in practice. Physical Therapy 97: 603–614.

- Dahl-Michelson T, Solbraekke K 2014 When bodies matter: Significance of the body in gender constructions in physiotherapy education. Gender and Education 26: 672–687.

- Doran B, Setchell J 2018 Performative acts of physiotherapy. In: Gibson B, Nicholls D, Setchell J, Groven K (Eds) Manipulating Practices: A Critical Physiotherapy Reader, pp. 125–149. Norway: Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP.

- Edwards S 1998 An anthropological interpretation of nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of the use of space and touch. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28: 809–817.

- Elllingson L 2017 Embodiment in Qualitative Research. Routledge: Oxford.

- Finlay L, Gough B 2003 Reflexivity. A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Flick U 2014 An Introduction to Qualitative Research (5th ed). London: Sage.

- Gallagher S 2013 A pattern theory of self. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 443.

- Gardner J, Williams C 2015 Corporal diagnostic work and diagnostic spaces: Clinicians’ use of space and bodies during diagnosis. Sociology of Health and Illness 37: 765–781.

- Grant B, Giddings L, Beale J 2005 Vulnerable bodies: Competing discourses of intimate bodily care. Journal of Nursing Education 44: 498–504.

- Hammond J 2009 Assessment of clinical components of physiotherapy undergraduate education: Are there any issues with gender? Physiotherapy 95: 266–272.

- Kelly M, Nixon L, McClurg C, Scherpbler A, King N, Dornan T 2018 Experience of touch in health care: A meta-ethnography across the health care professions. Qualitative Health Research 28: 200–212.

- Kertay L, Reviere S 1993 The use of touch in psychotherapy: Theoretical and ethical considerations. Psychotherapy Theory Research and Practice 30: 32–40.

- Kitzinger J 1994 The methodology of focus groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health and Illness 16: 103–121.

- Kordahl H, Fougner M 2017 Facilitating awareness of philosophy of science, ethics and communication through manual skills training in undergraduate education. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 33: 206–217.

- Moffat F, Kerry R 2018 The desire for ‘hands-on’ therapy – A critical analysis of the phenomenon of touch. In: Gibson B, Nicholls D, Setchell J, Groven K (Eds) Manipulating Practices: A Critical Physiotherapy Reader, pp. 174–193. Norway: Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP.

- Nicholls DA, Cheek J 2006 Physiotherapy and the shadow of prostitution: The society of trained masseuses and the massage scandals of 1894. Social Science and Medicine 62: 2336–2348.

- Nicholls DA, Gibson B 2010 The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 26: 497–509.

- Nicholls DA, Holmes D 2012 Discipline, desire and transgression in physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 28: 454–465.

- Normann B 2018 Facilitation of movement: New perspectives provide expanded insights to guide clinical practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice: 1–10. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1493165.

- Oberg G, Normann B, Gallagher S 2015 Embodied-enactive clinical reasoning in physical therapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 31: 244–252.

- Owen G 2014 Becoming a Practice Profession: A Genealogy of Physiotherapy’s Moving/Touching Practices. PhD Dissertation, University of Cardiff.

- Paterson M 2007 The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Roger J, Darfoiur D, Dham A, Hickman O, Shaubach L, Shephard K 2002 Physiotherapists’ use of touch in inpatient settings. Physiotherapy Research International 7: 170–186.

- Rose M 1999 ‘Our hands will know’: The development of tactile diagnostic skill- teaching, learning and situated cognition in a physical therapy programme. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 30: 133–160.

- Rudebeck C 2001 Grasping the essential anatomy: The roles of bodily empathy in clinical communication. In Toombs S (Ed), Handbook of Phenomenology and Medicine, (pp. 291–310). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Salzmann-Erikson M, Erikson H 2005 Encountering touch: A path to affinity in psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26: 843–852.

- Shaw R 2010 Embedding reflexivity within experiential qualitative psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 7: 233–243.

- Thornquist E 2006 Face to face and hands-on: Assumptions and assessments in the physiotherapy clinic. Medical Anthropology 25: 65–97.

- Toren C 1996 Ethnography: Theoretical background. In: Richardson JT (Ed) Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for Psychology and the Social Sciences, pp. 102–113. Leicester, UK: BPS Books.

- Tune D 2003 Is touch a valid therapeutic intervention? Early returns from a qualitative study of therapists’ views. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 1: 167–171.