ABSTRACT

Background

A person-centered and collaborative practice is considered crucial in contemporary physiotherapy. These ideals are often embraced in theory but are difficult to put into practice. As problems and solutions are related, understanding and refining theory on practical problems can close the knowing-doing gap and link the problem to the development of possible solutions.

Objective

To explore the challenges with providing physiotherapy as part of collaborative and person-centered rehabilitation services.

Methods

This article reports on an all-day interactive workshop with eight focus group discussions where physiotherapists from six different professional settings participated. We draw on theories of institutional logics to interpret the results.

Results

Challenges were linked to: 1) Professional level: Services being based on what the profession can offer – not on users’ needs; 2) Organizational level: Rewarding efficiency instead of user outcomes; and 3) System level: Not knowing the other service providers involved or what they are doing.

Conclusion

An innovative practice was constrained by multilevel social systems: the professional logic shaping the perceived professional scope, the organizational logic shaping the understanding of what was expected in the organizational context, and a system logic within a biomedical paradigm. Transforming and transcending these social systems is needed to realize collaborative and person-centered practice.

Introduction

Most health systems are organized from a biomedical understanding of illness that builds on acute, episodic models of care and focuses on disease-managing processes rather than peoples’ needs (Goodwin, Stein, and Amelung, Citation2017). The biomedical paradigm and a biomechanical view of the body have represented the organizing framework in traditional rehabilitation and physiotherapy services (Gibson, Citation2016; Nicholls, Citation2017; Nicholls and Gibson, Citation2010). As a result, services focus primarily on basic activities of daily living (ADL) and improving functional abilities, with limited access to long-term support (Cott, Wiles, and Devitt, Citation2007).

However, according to Norwegian rehabilitation law, rehabilitation must help the user achieve independence and involvement in school, work, social relationships, and society (Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Citation2018). When addressing needs beyond physical abilities, the concept of community integration is suited as it includes broader subjective aspects of life satisfaction, choice, and control of life (Cott, Wiles, and Devitt, Citation2007; Shaikh, Kersten, Siegert, and Theadom, Citation2019). For example, this concept entails components, such as independence, a sense of belonging, adjustment, having a place to live, being involved in meaningful occupational activity, and being socially connected to the community (Shaikh, Kersten, Siegert, and Theadom, Citation2019).

Aiming for community integration and participation in previously valued social activities and social roles requires physiotherapists to assist users in a problem-solving process, understanding their disabilities, and learning to manage their changed status or identity (Cott, Wiles, and Devitt, Citation2007; Wade, Citation2015). A physiotherapy practice supporting community integration could for example be facilitating reengagement in work or school activities (Egan et al., Citation2020). However, although what matters to users are often previously valued social activities and social roles, rehabilitation professionals, including physiotherapists, still tend to set the agenda, focusing on short-term functional goals and the acquisition of motor skills (Aadal, Pallesen, Arntzen, and Moe, Citation2018; Cott, Wiles, and Devitt, Citation2007; Hammond, Stenner, and Palmer, Citation2022).

Person-centered care has played an important role in moving healthcare practices from a limited biomedical, disease-focused approach to a more humanistic one (Gibson, Citation2016). The concept of person-centered care puts users in the center of a holistic approach, focusing on whole person needs, for example social, socio-economical, psychological and emotional needs (Håkansson Eklund et al., Citation2019; Zonneveld, Glimmerveen, and Minkman, Citation2021).

Recently Person Centered Rehabilitation has been conceptualized as a way of thinking about, organizing and delivering rehabilitation (Jesus et al., Citation2022; Kayes and Papadimitriou, Citation2023). In a person-centered rehabilitation practice collaboration is considered crucial, often requiring collaboration across disciplines, organizations, and sectors (Jesus et al., Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2020). Consequently, the World Health Organization (Citation2020) recently framed the Rehabilitation Competency Framework describing expected or aspired activities, knowledge, skills, competencies, values, and beliefs of the rehabilitation workforce, such as collaborative skills and teamwork activities.

However, while a person-centered and collaborative practice is considered a key component in contemporary physiotherapy practice, further development in implementing and applying new ideals is needed (Solvang and Fougner, Citation2016). Although physiotherapists often theoretically embrace the principles of person-centered practice, previous research has indicated difficulties with applying them in daily practice (Hammond, Stenner, and Palmer, Citation2022; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2022; Solvang and Fougner, Citation2016).

Fuglesang and Rønning (Citation2014) argued that an innovative practice is needed to implement rehabilitation policy ambitions, where practices of different kinds must be tied together and compromised in complex coacted structures, turning the ambitions into something concrete. An innovative practice is based on innovative behavior (i.e. new ways of doing things requiring a certain level of freedom or action space) (Berg, Citation2014). Hence to achieve change, the context of professional practice, such as organizational and cultural factors, is increasingly emphasized (Bokhour et al., Citation2018; Jesus et al., Citation2022; Morgan and Yoder, Citation2012). For example, time limits and demands, and organizational cultures prioritizing cost-efficiency may constrain person-centered rehabilitation (Kayes and Papadimitriou, Citation2023).

As society, health care systems, and the problems they are set to solve become more complex, changes in professional practice are required (Noordegraaf, Citation2011; Plsek and Greenhalgh, Citation2001). A pure professional practice focusing solely on diagnosing and treatment does not address the complex problems; thus, there is a call for more collaborative and connective professionalism (Andreassen, Citation2019; Noordegraaf, Citation2016). However, the complexity of the health and welfare sector, containing multiple professions, fields of knowledge and organizations, makes implementation of policy ambitions challenging (Vik and Hjelseth, Citation2022). Hence several scholars have encouraged research to understand the interactions and reinforcement of multiple factors and social systems involved (Breit and Andreassen, Citation2021; Vik and Hjelseth, Citation2022).

Changes in physiotherapy practices within the field of rehabilitation are needed; but knowledge on how to close the knowing-doing gap in realizing collaborative and person-centered practice is sparse. We explore challenges with a person-centered and collaborative physiotherapy practice, as experienced by physiotherapists from varied clinical settings in Northern Norway. We aimed to explore challenges with the collaborative physiotherapy practice part of person-centered rehabilitation services. This aim was addressed through the following research question: What challenges the collaborative physiotherapy practice part of person-centered rehabilitation services?

Theoretical perspective

The theory of institutional logics provides a link between patterns of practice and socially constructed rule structures (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). From this perspective, practice is embedded in social systems of beliefs, rules and assumptions which shapes actions (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury, Citation2012). To understand individual and organizational behavior, it must be located in the social and institutional context that influences agency (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008).

Health professionals provide most rehabilitation services within organizations. From the perspective of institutional theories, professionals are institutionally embedded in values, interests, and practices determined by the institutional logics of the organization (Andreassen, Citation2019; Noordegraaf, Citation2011). At the same time, professionals are obliged to follow professional standards and ethics (Evetts, Citation2010). The notion of a pure profession refers to standards and codes in terms of conduct, ethics, knowledge, skills, and experiences as controlled by the professionals (Noordegraaf, Citation2007). A pure profession is based on occupationally controlled logic and differs from professionals as situated or embedded in an organizational context and logic (Noordegraaf, Citation2007, Citation2011).

Since the rules and belief systems of institutions shape both the objectives of practice and the means by which such objectives are achieved, logics are also important in understanding change (Friedland, Citation1991). Action is understood as subjectivity guided by multiple, often contradictory or competing institutional logics (Friedland, Citation1991; Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). When individuals reinterpret actions and produce new truths, new behaviors and practices emerge (Friedland, Citation1991). In this way practice evolves historically and changes with the social system they spring from (Noordegraaf, Citation2011; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury, Citation2012). Several mechanisms can trigger change and lead to the modification of old logics (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). “Structural overlaps” is such a mechanism, meaning a new organizational form where actors from different logics are put together (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). In the context of rehabilitation, multidisciplinary teams can be understood as such a structural overlap. Structural overlaps can trigger change, as competing and contradictory logics come into contact (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). Another mechanism that can trigger change is “institutional entrepreneurs” or agents that create new or modify old institutions through access to resources. Structural overlaps can create opportunities for such institutional entrepreneurs (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008).

Service innovation can be thought of as developing new or existing practices (Skålén, Citation2018). Through the institutional logics perspective, physiotherapy practice is viewed as embedded in multi-level social systems of beliefs, rules and assumptions shaping action. Hence, to innovate services, understanding the social systems that physiotherapy practice is embedded or situated in, becomes crucial. In this study theory of institutional logics is applied to explore implicit constraints to an innovative physiotherapy practice as part of person-centered and collaborative rehabilitation practice. The analysis of perceived challenges as situated in social systems of institutional logics aims to contribute to service innovation in the field of rehabilitation through problem definition and theorization (Elg, Gremyr, Halldorsson, and Wallo, Citation2020).

Approach and research paradigm

This study is part of the larger project RehabLos (UiT Arctic University of Norway, Citation2023) and commits to a research paradigm of collaborative knowledge generation (Gibbons, Citation1999; Greenhalgh, Jackson, Shaw, and Janamian, Citation2016) that aims to combine scientific inquiry with active participation in a situation with two views in mind: 1) facilitate change; and 2) advance knowledge (Ram et al., Citation2014). Multi-actor collaboration is described as a key aspect in solving wicked or unruly public sector problems (Torfing, Citation2019). The exchange of different types of knowledge, competences and ideas between relevant and affected actors is believed to stimulate a process of mutual learning and innovation (Paavola, Lipponen, and Hakkarainen, Citation2004; Torfing, Citation2019).

Trying to find solutions to real-life problems enhances the implicit know-how skills of practitioners (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, and Lundvall, Citation2007). Making such tacit knowledge of experienced practitioners explicit can be an important part of an innovation spiral (Jensen, Johnson, Lorenz, and Lundvall, Citation2007; Paavola, Lipponen, and Hakkarainen, Citation2004). Problem identification and theorization (Elg, Gremyr, Halldorsson, and Wallo, Citation2020) are viewed as part of the researchers’ contribution to a collaborative innovation process.

Methods

This study is approved by The Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) and Data Protection Official for Research (659996). All participants gave their informed consent by signing a document with written information about the study and an ethical statement. The study was conducted in line with the Helsinki declaration (World Medical Association, Citation2013).

Study setting

The study was conducted in northern Norway and involved stakeholders in the field of rehabilitation services. The Norwegian health care system is divided into two governmental levels: specialized, hospital-based rehabilitation is the responsibility of the state and the Ministry of Health and Care Services via four regional health authorities. Community-based rehabilitation services are the responsibility of primary health services administered by municipalities. Norwegian Labor and Welfare Services (NAV) are responsible for national insurance benefits for all citizens and social welfare and employment (Vike, Citation2018). Due to several healthcare reforms, the overall responsibility for postacute rehabilitation has been transferred from hospitals to municipalities (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2020a). The physiotherapy part of rehabilitation is therefore offered in various contexts. In the municipality setting physiotherapists are organized in public health services and in private clinics partly financed by patient fees and public subsidies. In 2012, the Norwegian government initiated a coordination reform (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2008) in which general practitioners were assigned a key role in patient trajectories.

According to Norwegian rehabilitation law, rehabilitation must aim to assist the user in achieving independence and participation in education, working life, social relationships, and society (Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Citation2018). Integrated care in terms of collaboration and integration are central ambitions of Norwegian health care policies (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2020b; Vik and Hjelseth, Citation2022).

In 2001, Norway introduced an individual care plan to coordinate complex individual cases across sectors and service providers and enhance user involvement (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2020b). After being granted an individual care plan a case manager is appointed. Some municipalities have purchased a digital form of individual care plan, accessible to users, next of kin and all service providers involved regardless of organizational affiliation. However, individual care plans have remained significantly underused (Harsløf, Slomic, and Håvold, Citation2019).

This study draws on user experiences of persons with acquired brain injury. The injuries following an acquired brain injury (ABI) are often complex, affecting physical, cognitive, and social functioning and resulting in varied practical, emotional, and communicative challenges that often require long-term recovery and professional support (Arntzen, Borg, and Hamran, Citation2015). Hence acquired brain injury is a useful example of complex challenges requiring a changed professional practice.

Study design

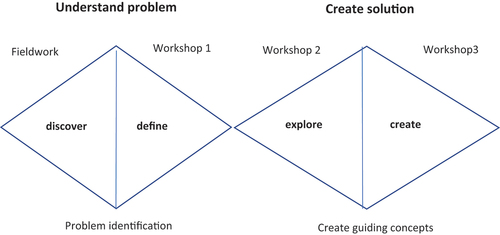

This study is part of the larger co-innovation project RehabLos aimed at developing a collaborative rehabilitation model to support community integration of people with ABI. Inspired by the “double diamond” design model (Design Council UK, Citation2023), field work and three all-day workshops were conducted over a period of 12 months with the goal of co-innovating a cross sectorial rehabilitation model for people with ABI (). The first workshop intended to identify challenges while the second and third workshop explored solutions.

Figure 1. Design process of the larger project inspired by the double diamond (Design Council UK, Citation2023).

This study is part of the problem identification phase of the project, theorizing material from the first workshop only. In this study we were interested in the first-hand experiences related to challenges with the collaborative physiotherapy practice part of person-centered rehabilitation services.

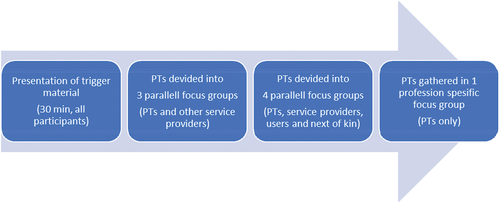

The all-day workshop started with a trigger presentation, followed by focus group discussions in mixed groups with additional stakeholders of the rehabilitation field including patients and next of kin (). Engaging participants with a wide range of professional backgrounds is in line with Elg, Gremyr, Halldorsson, and Wallo (Citation2020), who described that multiple-actor engagement brings forward complementary contextualized experiences that are relevant for sustainable service designs and enhance creative problem solving and innovation (Torfing, Citation2019; Windrum et al., Citation2016). At the end of the day the physiotherapists were gathered in a profession specific focus group with physiotherapists only ().

Figure 2. The all-day workshop with presentation of trigger material and the 8 focus groups where PTs participated.

Table 1. Participants of the eight focus groups where physiotherapists participated during the all-day workshop.

Recruitment and participants

We recruited six physiotherapists working in different organizational settings (). In addition, we recruited 18 stakeholders, including persons with ABI (n = 4), next of kin (n = 2), health care staff with experience with rehabilitation for persons with ABI (n = 10) (i.e. occupational therapists and registered nurses) and department managers (n = 2). These individuals were recruited as part of the larger project RehabLos to inform discussions with complementary perspectives. We contacted general managers of the different organizational settings who further recruited participants second hand, except from the physiotherapist with a private clinic who we contacted directly.

Table 2. The various organizational settings where the participating physiotherapists worked.

Preparations and trigger film

In advance of the workshop, the researchers conducted preparatory fieldwork, including videotaped interviews with users and health professionals who described challenges with rehabilitation services for persons with ABI. A month before the all-day workshop, the researchers invited the participants to a digital kickoff to provide information about the project and the research question of this study, as well as future studies planned.

The all-day workshop was introduced by a presentation with material intended to trigger reflections. In service design, a trigger film is a video material that is used to inspire and provoke discussion among participants in a workshop or co-creation session. The purpose of a trigger film is to stimulate creativity, facilitate communication, and generate new ideas and perspectives (Bate and Robert, Citation2007). Featuring user experiences that are relevant to the design challenge at hand and can help participants to focus on the end-users of the service rather than internal work processes (Bate and Robert, Citation2007).

The researchers chose 14 short clips (lasting from 30 seconds to 3 minutes) from the filmed video interviews. These clips were interwoven into a 30 min presentation of findings from fieldwork. The trigger films raised problems such as undetected disability, challenges with understanding one’s disability, and how disabilities, affect the family as a whole. One stroke survivor described how assessments failed to address psychosocial disability, as her not being able to take her children to gymnastics ().

Table 3. User in video interview used as trigger material introducing workshop 1.

Data development

After the introductory trigger film presentation, the participating physiotherapists () were divided into three mixed focus groups with other health care staff () for approximately 80 minutes. The participants were encouraged to share their immediate reactions to the trigger material, and then to reflect on the most significant problems and challenges to present rehabilitation services.

After a lunch break, the physiotherapists were divided into four new mixed focus groups, which in addition to mixed health care staff also included people with ABI and/or next of kin. In these focus groups, an exercise of describing the user trajectory through the health and welfare system was used to discuss current challenges. Finally, all of the physiotherapists were gathered in a mono-professional focus group with only physiotherapists from different organizational settings (). The physiotherapists were encouraged to share and discuss reflections throughout the day and the professional challenges with providing collaborative and person-centered services.

All focus group discussions were facilitated by 2–3 researchers in each group. The discussions were based on epistemological assumptions of knowledge and innovation as fundamentally social and interactive processes (Paavola, Lipponen, and Hakkarainen, Citation2004). Hence, the researchers’ role was to facilitate group discussions that focused on the outcome, supported and facilitated social processes, and engaged in democratic dialog and to participate in group discussions when considered fruitful (Gustavsen, Citation1996).

The focus group discussions were audiotaped and transcribed. In this study, we mainly focused on the physiotherapists’ experiences; hence, citations from the physiotherapists constitute the main data material in this article. However, the contributions and interactions with users and other stakeholders have informed and influenced the research and have shaped the context of collective sense-making in the focus group discussions.

Researcher reflexivity and user involvement

The research team consists of three physiotherapists and two occupational therapists with work experience from specialized and municipality-based health care services. Two of the authors are previous colleagues with some of the participating physiotherapists. The professional background of the research team may be perceived as beneficial due to their contextual knowledge and experiences. However, it was also important to be aware of the interrelations with some of the participants. Therefore, the research team conducted reflexive dialogs within the research team continuously throughout the process to adjust for the possible biases in personal interpretations.

The participating physiotherapists were invited to a digital meeting to discuss the result of the analysis. Two physiotherapists participated and confirmed that the results were representative of the participants’ contributions and reinforced the analysis with their reflections in line with the credibility criterion of member reflection (Braun and Clark, Citation2022; Creswell and Poth, Citation2018).

Analytical approach

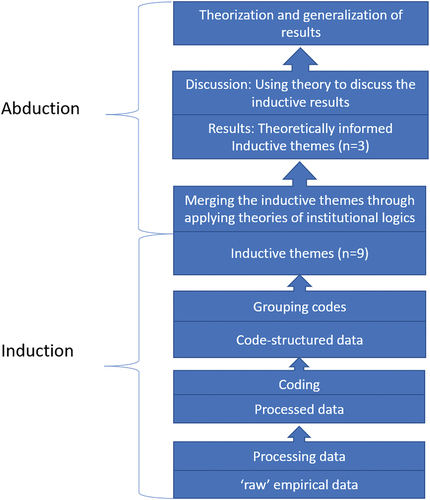

The data were analyzed in two rounds inspired by the “stepwise-deductive induction” described by Tjora (Citation2021) (). The research team read transcripts of the focus groups and the first author identified text relevant to answering the research question. To emphasize participants’ first-hand experiences, the researchers coded statements by physiotherapists inductively, creating codes that were closely related to the empirical text. The inductive codes were later grouped into inductive themes.

Figure 3. The analytic process inspired by Tjora (Citation2021) stepwise deductive induction: From empirical data to theorization and generalization of results applying a theoretical lens.

Based on the inductive analysis, we identified nine themes. The process of moving from inductive themes to more theoretically informed themes was performed by asking “What is this about?” and incorporating the theory of institutional logics and previous research in an abductive approach (Tjora, Citation2021). The interpretive discussion became an abductive process of exploring and explaining how different entities relate as part of a greater whole, asking: “What is the mechanism in this context?” (Ackroyd and Karlsson, Citation2014).

The theoretical, deductive analysis tried to reveal macrolevel factors and explanations of microlevel observations (Ackroyd and Karlsson, Citation2014). In this study, challenges can be empirically explored as perceived by the participating physiotherapists, while the mechanisms explaining these experiences are understood as hidden macro-level factors.

We anchor the analysis in the empirical material and first hand experiences of the physiotherapists by starting the analysis in an inductive manner. However, by applying the theoretical lens of institutional logics our ambition is not merely to describe the experiences but theorize the empirical results. This as a means of generalizing the findings (Tjora, Citation2021) and beginning the process of moving from problems to solutions (Elg, Gremyr, Halldorsson, and Wallo, Citation2020; Lee, Pries-Heje, and Baskerville, Citation2011).

Applying the institutional logics perspective (Friedland, Citation1991; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury, Citation2012) we identified logics at multiple levels; the professional level, the organizational level and the system level. This abductive part of the analysis resulted in merging themes into three theoretically informed themes that are presented as the results of this study. The following results section is an empirically driven presentation of the data, in accordance with the stepwise deductive analysis (Tjora, Citation2021). In the discussion section, the results are then examined using theoretical resources.

Results

In the following section, the results are presented with an inductive emphasis. The three main themes are presented with examples of quotations from the participants’ statements: 1) Professional level: Services being based on what each profession can offer – not on users’ needs; 2) Organizational level: Rewarding efficiency and not the outcome for the user; and 3) System level: Not knowing the other services providers involved or what they are doing. In this study user refers to users of healthcare services.

Professional level: services being based on what each profession can offer - not on users’ needs

Several physiotherapists reflected on today’s services not being designed to address complex issues. They described a lack of responsibility for assessing the actual needs of the service user and problematized that the assessments are limited to independence in managing basic physical needs, such as personal hygiene, dressing and eating. Furthermore, they called for “someone” to join users in a process of assessing and understanding psychosocial or functional problems related to community integration. Instead of engaging in such a process, they described that they try to assess whether users are in need of the service provided by them as physiotherapists.

When referring to their professional role as a physiotherapist and the physiotherapy profession, the physiotherapists all stressed treatment and examination that focuses on the physical body. Collaboration, phone calls, and psychosocial problems were discussed outside the profession’s core tasks. At the same time, they emphasized the necessity of moving beyond their profession-specific role to follow up on the patient’s needs. However, crossing professional boundaries was expressed as something requiring both experience and courage by a municipality-based physio-therapist:

… we have some structural frameworks that limit our full potential, I think, in terms of daring to embrace everything that is not about physical therapy. I also think that you need some experience and to be confident both as a person and have some [professional] expertise before you deviate from what is standard.

The participants described how physiotherapists have a lot to offer regarding rehabilitation that aims for social activities and community integration. Several participants expressed that physiotherapy as a physical approach working with the body implies “getting close to people, creating relationships”. They meant that they easily created close and trustful relationships with users and discussed private matters. They described themselves as competent, and one of them stated, “we could have done so much more if only we were allowed to” indicating a professional practice with more potential as being limited or restricted.

Being able to take your kids to gymnastics is an example of an activity in the social role of a parent. One physiotherapist discussed the current lack of assessments of such social activities and social roles and stated the following:

And then the physiotherapist let her go because she walked and talked, and she could say her name, and she could probably climb the stairs, so we let her go. And then the occupational therapist let go because she couldn’t specify what her challenges were, and then we have the GP who has a lot to do and can’t follow up, and then we couldn’t catch that she can’t actually follow her kids to gymnastics.

One physiotherapist reflected on how the lack of a more comprehensive or whole person assessment requires users to be able to comprehend and express their functional problems and needs:

So we expect them to be able to say, “These are my functional problems” (i.e. a month after a stroke, or two months after) so I think we are demanding way too much when we ask, “What matters to you?” A trillion things matter to me right now, but I cannot put my finger on them.

Organizational level: rewarding efficiency instead of outcome for the user

Several physiotherapists pointed out that the financial systems of both hospitals and private practice reward efficiency not outcome in terms of the patient’s need. They expressed that how efficient you are, is counted and measured in the number of consultations. One physiotherapist expressed that standardized checklists was a waste of time since a standardized approach fails to accommodate the individual needs of different users. A physiotherapist in the hospital ward described that an important aspect was to focus on the municipality to which the patient would be discharged. He described that this task makes him feel more like a lawyer than a physio-therapist, with the various municipalities having different systems and resources available.

… because we see that the hospital stay becomes shorter and shorter. The national guidelines describe up to two weeks, but few people stay inside for so long. They are discharged quickly, and what are they discharged to?

One hospital-based physiotherapist expressed that the more pressure and tighter the organizational frameworks become, the less willing one becomes to go beyond the perceived profession-specific tasks. He summarized that perceived pressure “sets you in a different direction than getting to know the person and his needs. Under great work pressure, assessments become narrow […] We get technical and forget to talk to people”. He argued that this pattern applied to all service providers involved, results in no one taking responsibility for life rehabilitation:

Which professional group is responsible for “life rehabilitation”? Or… the lives of people. No one is. Moreover, the more you push the frameworks… to the various professionals, the more you peel it down to the most “basic” one should attend to. Therefore, the physiotherapist becomes narrow on what the physiotherapists should be good at and spends their resources on that. The occupational therapist does the same thing, and then the nurses and the nursing staff do the same thing—they do the basic care and stuff that they reach over, and then they have to rush on to the next one, right, and they do the same thing there too. In addition, then there is nothing left for… (…) what one should perhaps have done.

However, when physiotherapists from different professional settings and organizations were asked to discuss challenges with a collaborative and person-centered practice, significant variations emerged. There were notable differences in the described opportunity for a practice that is in line with user needs. The municipality-based physiotherapists described how they worked mono-professionally with limiting organizational frameworks. These physiotherapists pointed to guidelines for waiting lists and priorities as limiting their practice. The physiotherapist in a private clinic described how the economic system restricts her and that she loses money if she does something other than treatment. She described how she had to detach herself from her frameworks and be willing to lose money to work more toward the patient’s needs. She clearly separated physiotherapy practice from the practice of rehabilitation by stating the following:

“The economic system is not designed for rehabilitation; it is designed for physio-therapy.”

On the other hand, the physiotherapists employed in hospital-based outpatient teams perceived their context of practice as flexible and absent of rigid frameworks. They described the teams as privileged, with autonomy in terms of tasks or what user problems to target.

… and then we have an advantage, I think - or we have a different position. (…) in that sense, we are privileged (…). We are not the ones who are in the middle of it with demands up to the ears.

These physiotherapists work in a multidisciplinary setting with a large degree of autonomy and described a practice that in many ways conforms to ideals of a collaborative and person-centered practice, targeting whole person needs. Notably, one of these physiotherapists stated that she no longer identified herself as a physiotherapist but rather a rehabilitator.

System level: not knowing the other service providers involved or what they are doing

While the hospital-based physiotherapists were organized in multi-professional teams, the physiotherapist in the municipality expressed that they worked by themselves. They described a sequential form of collaboration with other service providers that often was postponed until the end of a physiotherapy intervention. This communication was often limited to summarizing what has been done for others to be able to continue the process.

The physiotherapist with a private clinic even talked about herself in terms of being “alone on my little island”. She described it as challenging to achieve interdisciplinary collaboration and that there is a limit to what she as a physiotherapist can achieve on her own:

“Without the rest of the staff to collaborate with, I will hit the wall sooner or later.”

Physiotherapists from both the municipality and in the private clinic described the digital system for individual care plans as valuable. The system provided opportunities to send messages to a psychologist and speech therapist working in other organizations, in addition to enhance user involvement. However, several of the physiotherapists pointed out that very few are assigned an individual care plan for “the other 98% we have no arena for collaboration”.

One physiotherapist expressed the lack of “someone” who coordinates the rehabilitation process for all who are not assigned an individual care plan:

“But is there anyone in the process who asks, ‘How are you doing?’ (…) because then no one coordinates or follows up and … Whose job is it? Is it the GP’s … or?.”

The physiotherapists at the hospital inpatient ward described how they discharged patients without knowing what follows. Similarly, the physiotherapists in the municipality setting described that they rarely receive relevant information from the hospital. The exchange of information between staff at hospitals and staff in municipal services was described to be limited to written communication between physicians, where the physician at the hospital sends written information to the GP in the municipality setting. The physiotherapists expressed that information considered relevant to convey from the perspective of a physician at the hospital is different from the information sought by physiotherapists continuing the trajectory. One of the physiotherapists expressed that if he received the discharge summary, it was not always easy to understand what was written or the implications at the functional level, for everyday life or rehabilitation. Establishing a dialog with the GP was described as difficult.

The GP and I have no telephone contact, it does not work. So, there is electronic contact, which I do not know where it ends up. It goes out into cyberspace …

Several of the physiotherapists expressed that they wanted to discuss cases with the GP; however, the only medium was electronic communication with little opportunity for response. With the hospital sending separate referrals to different professionals all working in different organizations, “no one knows who the others are or what the others are doing,” as one of the physiotherapists stated. Often lacking information about other actors involved, the physio-therapists described a feeling of depending on the GP for communication.

I depend on it, the GP’s office, to which I send an electronic message without getting a reply. I hope that the GP will pass it on …

Collaboration or communication with the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Services (NAV) was not discussed by the physiotherapists. This became a theme of discussion only when it was specifically asked about. One of them stated that she “had no tradition” of collaborating with the Labor and Welfare Services. The interactive exercise in the mixed focus groups, working with the user trajectory, revealed that the physiotherapist had often ended their involvement when the work-ability assessment was made by the GP in collaboration with the Labor and Welfare Services.

Discussion

We explored challenges with the collaborative physiotherapy practice part of person-centered rehabilitation services. Through the analysis, we observed challenges linked to multiple-level logics: 1) Professional level: The services being based on what the profession can offer – not on users’ needs; 2) Organizational level: Rewarding efficiency instead of outcome for the user; and 3) System level: Not knowing the other service providers involved or what they are doing. In the following, we theorize our findings, by discussing the results based on theories of institutional logics (Friedland, Citation1991; Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury, Citation2012).

The health care system is a complex organizational field characterized by multiple coexisting and contradicting logics. In addition, there are several competing theories and approaches to practice within the profession of physiotherapy (Nicholls, Citation2017). The following analysis does not aim to present a comprehensive picture of all coexisting logics. Rather, it aims to illustrate how challenges perceived and expressed by physiotherapists can be understood as embedded in social systems on multiple levels. The following discusses professional practice as limited by: 1) perceived limits of the profession; 2) different organizational contexts; and 3) biomedical logic of the healthcare system.

Professional logic

The physiotherapists discussed their basic profession and their professional role in terms of physical assessment and treatment and by focusing on the physical body. Standard physiotherapy points to a traditional physiotherapy practice focusing on motor skills and the physical body (Gibson, Citation2016; Nicholls and Gibson, Citation2010). These skills and know-how are traditionally emphasized within the occupational profession. The discussion of the basic profession corresponds to what Noordegraaf (Citation2007) termed a pure profession. A pure profession refers to its logic, the standards and codes in terms of conduct, ethics, knowledge, and skills, and experiences as controlled by the professionals (Noordegraaf, Citation2007).

Collaboration, phone calls, and psychosocial problems were all discussed as being outside the core professional tasks. Studying the professional work of nurses Allen (Citation2015) separated patient care from organizing work and referred to the coordination and organization of patient trajectories. As pointed out by the World Health Organization (Citation2020) collaborative and connective tasks are particularly important for the physiotherapy part of rehabilitation services. For physiotherapy aimed at supporting community integration, such organizational or connective work was described as necessary.

Pursuing user needs was explicitly described as incompatible with sticking to a basic profession, and services based on such professional tasks, rather than user needs, were described as a core problem. In this sense, the results illustrate how physiotherapists theoretically embrace the ideals of a collaborative and person-centered practice but strive to realize such ideals in their daily practice. Understood from the perspective of institutional logics, practice is limited by the professional logic, which shapes perceptions of what constitutes the professional tasks. Occupationally controlled professional logic shapes the objectives of practice and the means by which such objectives are achieved (Friedland, Citation1991; Noordegraaf, Citation2007, Citation2011). This is consistent with the work of Andreassen (Citation2019) who noted that in the context of the rehabilitation field, professional logic shapes professionals’ perception of problems and their approach to these problems.

Statements such as “the economic system is not designed for rehabilitation; it is designed for physiotherapy” illustrate the perceived difference between a physiotherapy practice and a rehabilitation practice, understood as something more or different from a pure professional physiotherapy practice. According to Thornton and Ocasio (Citation2008) such processes of questioning dominating logics and incorporating new knowledge and new logics can be a source of institutional change. As multi-professional teams involve actors from different logics referred to as structural overlaps by Thornton and Ocasio (Citation2008); they can facilitate change. Hence physiotherapists working in such contexts can become institutional entrepreneurs, creating or modifying logics (Thornton and Ocasio, Citation2008). Interestingly, one of these physiotherapists no longer identified as a physiotherapist, illustrating the narrow frameworks of occupationally controlled logic.

The municipality-based physiotherapists expressed that deviating from routine behavior required courage, experience and economic security. This finding is consistent with Fuglesang and Rønning (Citation2014) who described that changes that are not based on explicit decision making can be perceived as possibly problematic and partly illegitimate.

The participants expressed that there were possibilities and potentials beyond what is perceived as standard professional practice, stating that “they could do so much more if only allowed to,” suggesting that practice is limited by “some structural frameworks.” When pointing to some structural frameworks, the institutional logics of several levels are represented simultaneously. While professional logic provides physiotherapists with an understanding of what constitutes their basic or pure profession, organizational logic shapes what they perceive as allowed in their current professional context. The findings are congruent with the work of Kayes and Papadimitriou (Citation2023) who likewise identified various levels of social systems as constraining person-centered rehabilitation.

Organizational logic

The results illustrated significant variations in terms of organizational contexts and prerequisites for an innovative professional practice. While the physiotherapists in hospital-based outpatient teams described a large degree of autonomy in terms of tasks, the municipality-based physiotherapists described working mono-professionally and with rigid frameworks. Tighter organizational frameworks were described to affect the perception of profession-specific tasks, narrowing the professional scope. Deviating from what is perceived as standard professional practice was described as demanding and requiring personal resources such as experience and courage. These results are supported by the work of Berg (Citation2014) who described innovative behavior as new ways of doing things and requiring a certain level of freedom or action space.

Without access to sufficient multidisciplinary collaboration – working alone “on their little island” what the municipality-based physiotherapist can achieve on their own was perceived as limited. This is consistent with the World Health Organization (Citation2020) Rehabilitation Competency Framework stressing collaborative work and participating in team forums as core activities for rehabilitation professionals. Without being able to include other professionals, addressing person-centered needs is in many instances not possible for physiotherapists (Cheng et al., Citation2016).

Consequently, the results indicate that although much of the responsibility for post-acute rehabilitation is transferred to the municipalities (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2020b) the municipality-based physiotherapists did not have the contextual prerequisites for a connective and collaborative practice targeting whole person needs. This result is consistent with previous research that has suggested that the preconditions for providing rehabilitation in primary care challenges physiotherapists to practice in novel ways (Irgens, Henriksen, and Moe, Citation2020b).

Being able to do so much more if only allowed to was a shared experience among all participating physiotherapists. Several physiotherapists pointed out that financial systems in both hospitals and private practice reward efficiency and not outcome in terms of user needs. This finding is consistent with the study of Levack, Dean, Siegert, and McPherson (Citation2011) who concluded that the prioritization of rehabilitation goals was largely influenced by financial and organizational factors.

Expressing the perceived demands of efficiency and productivity can be understood as a practice embedded in an organization based on a marked-based logic, often referred to within the concept of New Public Management. Fuglesang and Rønning (Citation2014) pointed out that although efficiency is important for public services, considering the scarcity of public money compared to demand, efficiency is not a main goal for the public sector. They suggested that public agencies are established for realizing public goals; therefore, effectiveness (i.e. realizing goals) should be the premier objective in the public sector. New Public Management is described as ill-suited to address complex challenges requiring cross-organizational collaboration as it focus on the efficiency of internal organizational processes (Eriksson and Hellström, Citation2021). Berg (Citation2014) found that the New Public Management logic of standardization can result in less freedom of action, hindering innovative behavior.

Andreassen and Fossestøl (Citation2014) pointed out that policy ambitions of collaborative rehabilitation services targeting person-centered needs and demands should include an active search for solutions, flexibility to address specific conditions of the individual’s situation, and collaboration that enables holistic services. Similarly, several scholars have stressed the reflexive, adaptive, responsive and collaborative nature of person-centered rehabilitation (Jesus et al., Citation2022; Kayes and Papadimitriou, Citation2023).,

Innovative activities in public sector services are often characterized by practitioners solving problems ad hoc, on the spot, related to the individual user, and without a particular plan or policy (Fuglesang and Rønning, Citation2014). Policy ambitions hold an implicit expectation of health professionals to move beyond their understanding of purpose and task embedded in the logics of their professions and organizations (Andreassen and Fossestøl, Citation2014). Hence, for practitioners to change practice in innovative manners, autonomy and flexibility are crucial (Fuglesang and Rønning, Citation2014).

Andreassen and Fossestøl (Citation2014) also pointed out that health and welfare organizations lack objectives, performance requirements and funding systems that support cross-sectorial collaboration. The organizations involved are mostly able to fulfill their internal organizational objectives independently of cooperation with others (Andreassen and Fossestøl, Citation2014). As an alternative to NPM, a service approach and integrative leadership in public management are suggested, stimulating the integration of resources across organizations and, therefore, being better suited to address complex issues (Eriksson and Hellström, Citation2021). Kayes and Papadimitriou (Citation2023) encouraged careful reflection on how one evaluates person-centered rehabilitation and what constitutes a good outcome. They proposed a thought experiment where the only performance metric that matters is users living the lives they want, and the long-term health and well-being of users is the outcome of primary interest.

System logic

Collaboration was described as sequential, without physical meetings. This observation is consistent with the work of Vik (Citation2018) and Vik and Hjelseth (Citation2022) who described healthcare as functionally differentiated, where the different actors and organizations work as autonomous systems that each maintain distinct functions.

The physiotherapists often lacked information on the other actors involved and the communication between the hospital and the municipality was described to mainly involve electronic messages between physicians, often irrelevant for physiotherapy practice. GPs were described as playing a pivotal role; however, they were difficult or almost impossible to reach. These results are consistent with the work of Andreassen (Citation2019) who described GPs as playing a key role while being distant and difficult to involve in collaborations. Irgens, Henriksen, and Moe (Citation2020a) also found that physiotherapists express a need for verbal communication and closer collaboration across health care levels and clinical settings, stating that hospital discharge summaries are necessary but not sufficient.

From the perspective of institutional logics, placing GPs and hospital-based physicians at the center of health trajectories illustrates how the health system is designed within a disease-based logic. The information considered relevant to convey from the perspective of a physician at the hospital is different from that sought by the physiotherapists who continue the trajectory. As the physio-therapists pointed out, they do not even understand all the information, as it is written from the logic of medical professionalism and involves different understandings of what information is relevant.

Vik and Hjelseth (Citation2022) suggested that the ambition of holistic services and a shared understanding among service providers is not only unrealistic but also obscures differences in need of attention. According to scholars (Fuglesang and Rønning, Citation2014; Vik and Hjelseth, Citation2022) dialog and discussions between actors from different professions and organizational settings are needed to negotiate a common understanding.

One of the municipality-based physiotherapists expressed that she had no tradition for collaborating with the Labor and Welfare Services (NAV). This result is consistent with another Norwegian study describing the collaboration between the Labor and Welfare Services and the healthcare sector as limited, challenging, and mostly restricted to involving GPs (Andreassen, Citation2019; Andreassen and Fossestøl, Citation2014). The work-ability assessment is an issue treated by GPs, who have been criticized for focusing on disease and diagnosis rather than functional assessments and work ability (Andreassen and Fossestøl, Citation2014).

Diseased-based and self-contained silo curative care models are now considered to undermine the ability of health systems to provide high-quality and financially sustainable care (Goodwin, Stein, and Amelung, Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Several scholars have argued that it is a complex endeavor to transform healthcare systems to better serve whole person needs, as it requires a systems level approach as well as a fundamental shift in practice and healthcare structures (Bokhour et al., Citation2018; Kayes and Papadimitriou, Citation2023).

Envisioning rehabilitation and physiotherapy based on a biomedical paradigm reduces services to a set of biomechanical procedures aimed at normalization through the correction of motor impairments (Egan et al., Citation2020). In an alternate vision of postdischarge rehabilitation, services could be envisioned as a self-management intervention with the goal of reengaging in valued activities and social roles (Egan et al., Citation2020). In such a vision, rather than ending involvement after a period of interventions targeting motor impairments, physiotherapists contribute to a long-term rehabilitation process, facilitating reengagement in work or other forms of participation and community integration.

Strengths and limitations

As science changes so does the view of what constitutes good quality research (Belcher, Rasmussen, Kemshaw, and Zornes, Citation2016; Gibbons, Citation1999; Østensjø and Askheim, Citation2019). According to Østensjø and Askheim (Citation2019) research quality is no longer only about scientific quality but also about how the research fulfills societal interests and values and contributes to innovation. By thematical and theoretical analysis of perceived challenges, this study contributes to service innovation through problem identification and theorization (Elg, Gremyr, Halldorsson, and Wallo, Citation2020).

We apply several strategies for enhanced methodological quality and credibility as described by Creswell and Poth (Citation2018). The period of preparatory fieldwork and video recording of interviews used as trigger material introducing the workshop, together with an all-day interactive workshop, resulted in prolonged engagement in the field with several occasions and possibilities to engage in collaborative sense-making and reflection with the participants, including user representatives. The preparatory work, including fieldwork observations, filmed individual interviews, and later data collection through focus group discussions allowed for a triangulation of sources that informed the research. We also argue that discussing the inductive and deductive analysis with two of the participating physiotherapists increases the credibility of the study.

The composition of focus group participants, with a strategic selection of physiotherapists from six different professional settings, as well as other health professionals and people with ABI, provided interesting and fruitful group discussions. A limitation, however, is that the results of this study are based on focus group discussions with a limited number of participants from one region of Norway. Including data with statements of people with ABI and other health professionals could have provided a broader perspective of current challenges to physiotherapy practice. Additionally, including several physiotherapists from other contexts could have resulted in somewhat different findings. Therefore, our results may highlight challenges that need translation and contextual discussion if they are transferrable to other regions in Norway or an international context.

Conclusions and implications

We explore challenges with the collaborative physiotherapy practice part of person-centered rehabilitation. The empirical results illustrate how such a physiotherapy practice is challenged by multilevel social systems: a professional logic shaping the perceived professional scope and an organizational logic of efficiency, service-centeredness, and internal organizational objectives. A system logic within a biomedical paradigm is additionally constraining. Our results indicate that limited flexibility and autonomy constrain the innovative practice necessary to implement a collaborative and person-centered practice. To translate ideals into practice, this complexity should be addressed by aspiring to transcend and transform these social systems. Expanding the professional scope of physiotherapy and making organizational or connective tasks explicit parts of the profession appear crucial. Additionally, designing services based on user needs, where the organizational context facilitates a collaborative and person-centered practice, is necessary. Further development of how to operationalize ideals of practice into the everyday realities of physiotherapists is needed. In doing so, an alternate theoretical framework for post-discharge physiotherapy appears crucial. As problems and solutions are closely related, we form a platform for action in service innovation. Through further work we aim to theorize the material from the second and third workshop () supporting co-innovation and piloting of a model for collaborative and person-centered rehabilitation services.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Norwegian Fund for Post-Graduate Training in Physiotherapy under Grant Number 129514.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aadal L, Pallesen H, Arntzen C, Moe S 2018 Municipal cross-disciplinary rehabilitation following stroke in Denmark and Norway: A qualitative study. Rehabilitation Research and Practice 2018: 972190. 10.1155/2018/1972190

- Ackroyd S, Karlsson JC 2014 Critical realism, rearch techniques, and research designs. In: Edwards OJ Vincent S (Eds) Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide, pp. 21–45. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665525.003.0002

- Allen D 2015 The Invisible work of nurses: Hospitals, Organisation and healthcare. New York: Routledge.

- Andreassen TA 2019 Complex problems in need of inter-organizational coordination: The importance of connective and collaborative professionalism within an organizational field of rehabilitation. In: Harsløf I, Poulsen I Larsen K (Eds) New Dynamics of Disability and Rehabilitation: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 225–249. Singapore: Springer Verlag. 10.1007/978-981-13-7346-6_10

- Andreassen TA, Fossestøl K 2014 Utfordrende inkluderingspolitikk: Samstyring for omforming av institusjonell logikk i arbeidslivet, helsetjenesten og NAV. [Developing a holistic and user centered employment and welfare service]. Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 55: 174–202. 10.18261/ISSN1504-291X-2014-02-02

- Arntzen C, Borg T, Hamran T 2015 Long-term recovery trajectory after stroke: An ongoing negotiation between body, participation and self. Disability and Rehabilitation 37(18): 1626–1634. 10.3109/09638288.2014.972590

- Bate P, Robert G 2007 Bringing user experience to healthcare Improvement: The Concepts, Methods and practices of experience-based Design. London: CRC Press.

- Belcher BM, Rasmussen KE, Kemshaw MR, Zornes DA 2016 Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context. Research Evaluation 25(1): 1–17. 10.1093/reseval/rvv025

- Berg AM 2014 Organizing for innovation in the public sector. In: Fuglesang L, Rønning R Enquist B (Eds) Framing Innovation in Public Service Sectors, pp. 130–147. New York: Routledge.

- Bokhour BG, Fix GM, Mueller NM, Barker AM, Lavela SL, Hill JN, Solomon JL, Lukas CV 2018 How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BMC Health Services Research 18(1): 168. 10.1186/s12913-018-2949-5

- Braun V, Clark V 2022 Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. SAGE Publications Inc International Journal of Transgender Health. 24(1): 1–6. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

- Breit E, Andreassen TA 2021 Organizational views on collaboration in welfare services. Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 24: 7–20. 10.18261/issn.2464-3076-2021-01-02

- Cheng L, Leon V, Liang A, Reiher C, Roberts D, Feldthusen C, Mannerkorpi K, Dean E 2016 Patient-centered care in physical therapy: Definition, operationalization, and outcome measures. Physical Therapy Reviews 21(2): 109–123. 10.1080/10833196.2016.1228558

- Cott CA, Wiles R, Devitt R 2007 Continuity, transition and participation: Preparing clients for life in the community post-stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation 29(20–21): 1566–1574. 10.1080/09638280701618588

- Creswell JW, Poth CN 2018 Qualitative Inquiry and research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches (4th). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Inc.

- Design Council UK 2023 Framework for innovation. Design Council. London, England. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/framework-for-innovation/

- Egan MY, Laliberté-Rudman D, Rutkowski N, Lanoix M, Meyer M, McEwen S, Collver M, Linkewich E, Montgomery P, Quant S, et al. 2020 The implications of the Canadian stroke Best practice Recommendations for design and allocation of rehabilitation after hospital discharge: A problematization. Disability and Rehabilitation 42(23): 3403–3415. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1592244

- Elg M, Gremyr I, Halldorsson Á, Wallo A 2020 Service action research: Review and guide-lines. Journal of Services Marketing 34: 87–99. 10.1108/JSM-11-2018-0350

- Eriksson E, Hellström A 2021 Multi‐actor resource integration: A service approach in public management. British Journal of Management 32(2): 456–472. 10.1111/1467-8551.12414

- Evetts J 2010 Reconnecting professional occupations with professional organizations: Risk and opportunities. In: Svensson L, and Evetts J (Eds) Sociology of Professions: Continental and Anglo-Saxon traditions, pp. 123–144. Göteborg, Sweden: Daidalos.

- Friedland R 1991 Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In: Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ (Eds) The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, pp. 232–263. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fuglesang L, Rønning R 2014 Introduction framing innovation in public service sectors: A contextual approach. In: Fuglesang L, Rønning R Enquist B (Eds) Framing Innovation in Public Service Sectors, pp. 1–17. New York: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315885612

- Gibbons M 1999 Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 402(Suppl 6761): 81–84. 10.1038/35011576

- Gibson B 2016 Rehabilitation: A post-critical approach. Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press.

- Goodwin N, Stein V, Amelung V 2017 What is integrated care? In: Amelung V, Stein V, Goodwin N, Balicer R, Nolte E Suter E (Eds) Handbook of Integrated Care, pp. 3–24. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5_1

- Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T 2016 Achieving research impact through co‐creation in community‐based health services: Literature review and case study. The Milbank Quarterly 94(2): 392–429. 10.1111/1468-0009.12197

- Gustavsen B 1996 Action research, democratic dialogue, and the issue of “critical mass” in change. Qualitative Inquiry 2: 90–103. 10.1177/107780049600200113

- Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, Kaminsky E, Skoglund K, Höglander J, Sundler AJ, Condén E, Summer Merenius M 2019 “Same same or different?” a review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling 102: 3–11. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029

- Hammond R, Stenner R, Palmer S 2022 What matters most: A qualitative study of person-centered physiotherapy practice in community rehabilitation. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 38(9): 1207–1218. 10.1080/09593985.2020.1825577

- Harsløf I, Slomic M, Håvold OK 2019 Establishing individual care plans for rehabilitation patients: Traces of self-targeting in the norwegian universal welfare state. Nordic Journal of Social Research 10: 24–47. 10.7577/njsr.2686

- Irgens EL, Henriksen N, Moe S 2020a Communicating information and professional knowledge in acquired brain injury rehabilitation trajectories - a qualitative study of physiotherapy practice. Disability and Rehabilitation 42: 2012–2019. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1544295

- Irgens EL, Henriksen N, Moe S 2020b Variations in physiotherapy practice in neurological rehabilitation trajectories - an explorative interview and observational study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 36: 95–107. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1480679

- Jensen MB, Johnson B, Lorenz E, Lundvall BA 2007 Forms of knowledge and modes of innovation. Research Policy 36: 680–693. 10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.006

- Jesus TS, Papadimitriou C, Bright FA, Kayes NM, Pinho CS, Cott CA 2022 Person-centered rehabilitation model: Framing the concept and practice of person-centered adult physical rehabilitation based on a scoping review and thematic analysis of the literature. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 103(1): 106–120. 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.05.005

- Kayes NM, Papadimitriou C 2023 Reflecting on challenges and opportunities for the practice of person-centred rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation 37(8): 1026–1040. 10.1177/02692155231152970

- Lee JS, Pries-Heje J, Baskerville R 2011 Theorizing in design science research. In: Jain H, Sinha A Vitharana P (Eds) Service-Oriented Perspectives in Design Science Research: DESRIST, pp. 1–16. Berlin, GermanyBerlin Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-20633-7_1

- Levack WM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, McPherson KM 2011 Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: How clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Education and Counseling 85: 206–213. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.011

- Morgan S, Yoder LH 2012 A concept analysis of person-centered care. Journal of Holistic Nursing 30(1): 6–15. 10.1177/0898010111412189

- Nicholls DA 2017 The end of physiotherapy. New York: Routledge.

- Nicholls DA, Gibson BE 2010 The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 26(8): 497–509. 10.3109/09593981003710316

- Noordegraaf M 2007 From “pure” to “hybrid” professionalism: Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration and Society 39(6): 761–785. 10.1177/0095399707304434

- Noordegraaf M 2011 Risky business: How professionals and professional fields (must) deal with organizational issues. Organization Studies 32(10): 1349–1371. 10.1177/0170840611416748

- Noordegraaf M 2016 Reconfiguring professional work: Changing forms of professionalism in public services. Administration and Society 48(7): 783–810. 10.1177/0095399713509242

- Norwegian Directorate of Health 2008 White Paper no 47 (2008-2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett Behandling - På Rett Sted - Til Rett Tid [the coordination Reform. Proper treatment - at the right Place and right time]. Oslo, Norway.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health 2020a Evaluering av Opptrappingsplan for Habilitering og Rehabilitering (2017-2019). [Evaluation of the Escalation plan for Habilitation and rehabilitation]. Oslo, Norway. https://helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter

- Norwegian Directorate of Health 2020b Nasjonal Veileder: Rehabilitering, Habilitering, Individuell plan og Koordinator. [national guidelines: Rehabilitation, Habilitation, individual care plans, and care manager]. Oslo, Norway. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere.

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services 2018 Forskrift om Habilitering og Rehabilitering, Individuell plan og Koordinator [Regulations on Habilitation and rehabilitation, individual care plans and care manager]. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care. Oslo, Norway. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2011-12-16-1256.

- Østensjø S, Askheim OP 2019 Forskning med nye aktører – Forskningskvalitet og nytteverdi. [Research with new stakeholders - Research quality and usefulness. In: Askheim O, Lid I Østensjø S (Eds) Samproduksjon i Forskning: Forskning med nye Aktører [Co-Production in Research: Research with New Players, pp. 231–245. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. 10.18261/9788215031675-2019-14

- Paavola S, Lipponen L, Hakkarainen K 2004 Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research 74(4): 557–576. 10.3102/00346543074004557

- Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T 2001 Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. British Medical Journal 323(7313): 625–628. 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625

- Ram M, Edwards PK, Jones T, Kiselinhev A, Muchenje L 2014 Pulling the levers of agency: Implementing critical realist action research. In: Edwards OJ Vincent S (Eds) Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide, pp. 205–222. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665525.003.0011

- Shaikh NM, Kersten P, Siegert RJ, Theadom A 2019 Theadom a 2019 developing a comprehensive framework of community integration for people with acquired brain injury: A conceptual analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation 41(14): 1615–1631. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1443163

- Sjöberg V, Forsner M 2022 Shifting roles: Physiotherapists’ perception of person-centered care during a pre-implementation phase in the acute hospital setting - a phenomenographic study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 38(7): 879–889. 10.1080/09593985.2020.1809042

- Skålén P 2018 Service logic. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Solvang PK, Fougner M 2016 Professional roles in physiotherapy practice: Educating for self-management, relational matching, and coaching for everyday life. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 32(8): 591–602. 10.1080/09593985.2016.1228018

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W 2008 Institutional logics. In: Greenwood R, Oliver C, Sahlin K Suddaby R (Eds) The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, pp. 99–128. SAGE Publications Inc. 10.4135/9781849200387.n4

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M 2012 The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to Culture, Structure and process. Oxford University Press.

- Tjora A 2021 Kvalitative Forskningsmetoder i Praksis (4th ed). [qualitative research Methods]. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Torfing J 2019 Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. Public Management Review 21(1): 1–11. 10.1080/14719037.2018.1430248

- UiT Arctic University of Norway 2023 RehabLos. Tromsø, Norway. https://uit.no/project/rehablos

- Vik E 2018 Helseprofesjoners samhandling - en litteraturstudie. [coordination between health care professions - a scoping review]. Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 21: 119–147. 10.18261/issn.2464-3076-2018-02-03

- Vike H 2018 Politics and Bureaucracy in the Norwegian welfare state: An Anthropological approach. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1007/978-3-319-64137-9

- Vik E, Hjelseth A 2022 Integration of health services - Eight theses on coordination in a functionally differentiated healthcare system. Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 63: 122–140. 10.18261/tfs.63.2.3

- Wade D 2015 Rehabilitation - a new approach. Part two: The underlying theories. Clinical Rehabilitation 29: 1145–1154. 10.1177/0269215515601175

- Windrum P, Schartinger D, Rubalcaba L, Gallouj F, Toivonen M 2016 The co-creation of multi-agent social innovations: A bridge between service and social innovation research. European Journal of Innovation Management 19(2): 150–166. 10.1108/EJIM-05-2015-0033

- World Health Organization 2017 Rehabilitation in health systems. http://www.who.int/en/.

- World Health Organization 2020 Rehabilitation Competency framework.

- World Medical Association 2013 World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 310(20): 2191–2194. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

- Zonneveld N, Glimmerveen L, Minkman M 2021 Values in integrated care. In: Amelund V, Stein V, Suter E, Goodwin N, Nolte E Balicer R (Eds) Handbook Integrated Care (2nd), pp. 53–66. 10.1007/978-3-030-69262-9_4