ABSTRACT

The modern valuation profession faces a significant challenge in providing high-quality narrative reports that are both effective and customisable. Clear communication of the valuation story is essential, yet there is a recognised gap in understanding how to implement storytelling successfully within narrative valuation reports. This study aims to bridge this gap using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 19 New Zealand valuers to explore the essential principles of crafting effective narrative valuation reports. This study identifies six critical components of valuation storytelling that are necessary for a high-quality narrative report: accuracy, balance, clarity, data-driven, efficiency in using multimodal tools, and reporting flawlessness. The establishment of strong relationships and robust processes within valuation practices is emphasised to reinforce these principles. This study also proposes a conceptual framework for valuation storytelling and suggests incorporating this framework into professional guidelines to equip emerging valuers with compelling narrative valuation reports.

Introduction

Reporting is an inherent component of a valuation process. Valuers use their reports to document their work and communicate their opinions (Crosby et al., Citation1997; Pardue, Citation1990). A valuation report enables users to make informed decisions based on a clear and logical understanding of the valuation (Adair & Hutchison, Citation2005). This ensures that users have access to all the relevant information needed to assess the reliability and credibility of the valuation. Transparency is essential for maintaining trust and confidence in the valuation profession (Carsberg, Citation2002; Mallinson, Citation1994).

One way valuers report is through a narrative valuation report, which is the most detailed and customisable format for reporting valuation conclusions (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020). This approach is supported by relevant valuation standards such as Standard C of the Appraisal Institute Standards of Valuation Practice, IVS 103 of the International Valuation Standards Council, Standard 2 of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, and VPS3 of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyor Red Book to ensure the quality and accuracy of narrative reports. According to these standards, it is mandated that narrative valuation reports communicate valuation outcomes clearly, accurately, and in a non-misleading manner and contain sufficient information and a comprehensive explanation of valuation analysis and reasoning to convince the reader of the soundness of the value opinion. These attributes are further enhanced by good composition, a fluid writing style, and clear expression (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020).

Despite prescribed standards, the recurring problem that the modern valuation profession continues to face in many parts of the world is the provision of consistently high-quality narrative valuation reporting that is reliable, effective, and customisable (Amidu et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2011; Sladack, Citation1991). Over the past several years, the form and substance of narrative valuation reports prepared by valuers have come under increasing scrutiny by clients, with an emphasis on the scope of information provided (story) and the way in which they communicate information (storytelling). For instance, in New Zealand, the Valuers Registration Board (VRB) has documented several high-profile cases involving complaints lodged against valuers in accordance with the Valuers Act of 1948. In most cases, a common charge is the failure to exercise utmost care and faith in ensuring the maintenance of the highest standards in the preparation of the valuation report. In one of the most recent cases involving Valuer W (2020) NZVRB 4, the VRB found that Valuer W had breached IVS 103 reporting by failing to disclose a limiting condition relevant to the valuation, specifically the failure to communicate the risk and uncertainty surrounding the various valuation inputs.

Similar cases of poor reporting practices have also been highlighted in various academic studies that have evaluated the quality and content of narrative valuation reports in countries such as the US (Colwell & Trefzger, Citation1992; Dotzour & Le Compte, Citation1993; Knitter, Citation1995), the UK (Crosby et al., Citation1997), and Australia (Newell, Citation1999, Citation2004), concluding that there is a need for improvement in the provision of information within valuation reports. Facilitating valuers to effectively communicate valuation stories in their reporting is not only considered a professional practice that impacts the valuer’s work, but also a powerful means to help users who are interested in how a valuer comes to a value conclusion (the valuation process), including the factors considered, methodologies employed, and rationale behind the final valuation figure (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020; Pardue, Citation1990).

Storytelling is the process by which people communicate their experiences and make sense of the world (Drumm, Citation2013). It allows organisational actors to create meaning through the exchange of stories (Dessart & Pitardi, Citation2019; Jones & Comfort, Citation2018). Throughout history, it has been used as an efficient tool for sharing contrasting perspectives and creating balance (Lugmayr et al., Citation2017). Storytelling is used as a professional tool in various disciplines, including marketing (Fog, Citation2010; Vincent, Citation2002), health (Hardy & Sumner, Citation2018; Slivinske & Slivinske, Citation2011), and education (Bruce et al., Citation2020; Jamissen et al., Citation2017) to bring about positive changes for clients and promote best practices for professionals. While studies that attempt to explain the role of storytelling in professional valuation practices are emerging (Amidu et al., Citation2021), there is a lack of understanding of how to successfully implement it in narrative valuation reports. This study aims to provide essential principles for crafting effective narrative valuation reports by examining how valuers tell successful valuation stories in their practice.

This study focuses on organisational storytelling and the crafting of data narratives as a form of storytelling. This research aims to explore the application of these approaches within the context of professional valuation practice and to investigate how they contribute to the successful construction of valuation stories in narrative reporting practice.

This study begins by examining the types of written valuation reports and important elements of narrative valuation reporting, drawing on the most recent industry practice standards and literature. An overview of extant studies is then provided to unpack the different aspects of storytelling and to provide the context for this study. Specifically, this study argues that focusing on the art and craft of storytelling has the potential to convey clear and powerful messages that help others develop their knowledge, skills, and understanding.

Literature review

Written valuation reports

The primary purpose of a valuation report is to communicate the necessary information to the client effectively and clearly, enabling them to make informed financial decisions. Additionally, the valuation report serves as a permanent record of the valuation, which can be referenced by the client, valuer, or utilised in any subsequent legal proceedings, such as court cases or arbitration hearings. It is important to note that valuation reports are often shared with third parties who may not possess the same level of familiarity with the property as the client or valuer. Consequently, it is imperative that valuation reports are crafted in a manner that ensures clarity and comprehensibility regardless of the reader’s familiarity with the property.

There are different formats for written valuation reports which fall broadly into two types: short-form reports and narrative reports (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020).

Short-form valuation reports

Short-form reports are characterised by their standardised templates and concise nature, often adhering to established industry guidelines and regulations. These reports are commonly used by institutional clients, such as large insurance and lending institutions, and government agencies, for various valuation purposes. As these entities review many valuation reports, using a standard report form is both efficient and convenient. However, valuers have a duty to ensure that the property is fully described and that all important and relevant items are covered, even if it means deviating from the standard form by submitting an addendum or a supplementary report.

Criticism and concern have been raised regarding ‘short-form’ reporting, particularly in cases in which clients seek to save costs and expedite processing. This practice often involves the use of ‘tick-in-the-box’ one- or two-page form reports, where standard answers are ticked or crossed, and minimal descriptive information is provided. The potential danger of such practices lies in the reduction of standards, as valuers may be tempted to do the minimum required to complete the form, compromising the thoroughness of property inspection, research on comparable evidence, and compliance with legal, ethical, and valuation standards. Furthermore, it may undermine the professionalism of valuers, giving the impression that valuation can be carried out by anyone simply filling in the ‘boxes’.

Narrative valuation reports

Narrative reports are the longest and most formal valuation reports. These reports are tailored to provide a more comprehensive and detailed account of the valuation process and its outcomes. Narrative valuation reports often incorporate a narrative style, offering in-depth explanations and analyses to ensure that the client is equipped with a thorough understanding of valuation findings. This format is particularly beneficial when the client requires a more nuanced and contextualised assessment of the property’s value as well as when the report is intended for dissemination to third parties who may benefit from a more comprehensive overview of the valuation.

For relatively straightforward properties, a client-oriented report that presents essential information on the first page with additional details and the valuation methodology following is preferred. This format efficiently satisfies client requirements, as clients often scan valuation reports to extract essential facts and recommendations. However, in cases in which specific aspects of the property require careful consideration, the report may be read in detail. In contrast, for complicated properties, it may be necessary to provide only a summary of the valuation on the first page, with detailed statements and calculations included later in the report or appendices.

Narrative valuation reports vary significantly in content and organisation depending on the client’s specific requirements and the complexity of the asset; however, they typically contain specific elements that follow the sequential steps of the valuation process (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020). Most narrative valuation reports prepared by members of the Appraisal Institute consist of four major parts that can be formally divided into subheadings or presented as continuous narratives. These fundamental components are (1) introduction, (2) identification of the appraisal problem and scope of work, (3) presentation of data, and (4) analysis of the data and conclusions. Additionally, many reports include a fifth section, the addenda, which incorporates supplementary information and illustrative material that would otherwise disrupt the main body of the report (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020). The IVSC also requires written narrative reports to include precise and comprehensive descriptions of the assignment’s scope, purpose, intended use, usage limitations, and significant uncertainty or limiting conditions that directly impact valuation (IVSC, Citation2022). The importance of these narrative structures and the content of a valuation report lies in ensuring transparency and presenting the valuation process logically and coherently (Amidu et al., Citation2021).

In a well-written narrative valuation report, the valuer provides comprehensive and compelling support and rationale for their opinions and conclusions to persuade the reader about the validity of the final opinion. It is imperative to segregate the descriptive sections from the analysis and interpretation, presenting factual and descriptive data early in the report, to facilitate subsequent analysis and interpretation. Avoiding unnecessary duplications is essential, and the valuer should tailor the data presentation to the nature and complexity of the valuation problem (Appraisal Institute, Citation2020; Pardue, Citation1990).

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of narrative valuation reports, it is essential to adhere to established principles and best practices in report-writing. Blankenship (Citation1998) outlined several principles of effective valuation report-writing:

Clarifying the organisation of the report

Visualising the organisation through techniques such as a six-step market analysis process as an outline for the report.

Employing standard publishing techniques

Utilising graphics as powerful reporting tools

Ensuring calculations are surrounded by white space for clarity and ease of reference.

Incorporating tables and spreadsheets effectively

Pie charts, line graphs, and bar graphs were used to reveal relationships and trends in the data.

Placing graphics and exhibits strategically.

Labelling and numbering exhibits for easy reference and navigation within the report.

Pardue (Citation1990) also provided insights into the essentials of appraisal report writing, which complements Blankenship’s principles. Adherence to these principles and best practices is crucial to producing high-quality valuation reports. These guidelines not only enhance the clarity and organisation of the report but also contribute to the overall effectiveness of conveying valuation information to the intended audience.

In summary, the effective preparation and presentation of narrative valuation reports is crucial for ensuring transparency, logical coherence, and persuasive communication between the valuation process and conclusions. Nevertheless, valuers often inadvertently produce reports that, while technically well-prepared, may lack clarity for many clients (Amidu et al., Citation2021; Sladack, Citation1991). Studies on the quality and content of valuation reports suggest room for improvement in the provision of information in these reports (Crosby, Citation2000; Knitter, Citation1995; Newell, Citation2004). This suggestion underscores the importance of understanding and meeting client expectations (Crosby et al., Citation1997; Newell et al., Citation2010) and highlights the role of storytelling in the production of effective narrative valuation reports. A recent study by Amidu et al. (Citation2021) argued that a quality valuation report should tell a clear story of the valuation process, including the factors considered, methodologies employed, and rationale behind the final valuation figure. However, the extent to which practising valuers successfully implement storytelling in narrative valuation reports has yet to be investigated.

Storytelling imperative in narrative valuation reporting

This study emphasises organisational storytelling and the crafting of data narratives as a form of storytelling. This study focused on applying these approaches to the professional practice of narrative valuation reporting.

Narrative valuation reports are often characterised by complex data and technical information that may be difficult for clients to comprehend. Incorporating storytelling into reports can be an effective means of communication for addressing this challenge. Using data storytelling, valuers can bring property to life by providing a narrative that goes beyond numbers and technical detail. Dykes (Citation2019, pp. 97–1010) outlines six essential elements for crafting a compelling data story. First, the foundation of a data story lies in the quality and accuracy of the data, which significantly influence its success and credibility. Second, it is crucial to have a central theme of data support to ensure that the story remains focused and purposeful. Third, a data story should move beyond mere description to provide deeper analytical reasoning and to explain the underlying causes and implications. Fourth, by presenting data in a linear sequence, unfolding information gradually leads to central insights and enhances the story’s impact. Fifth, providing a contextual background and omitting non-essential information are essential, akin to crafting a movie script, to ensure that the audience can fully appreciate the insights. Finally, incorporating visual representations of data is vital because they are more powerful than words alone in conveying information. Following a structured process, data storytelling can elevate a report from a collection of facts into a compelling narrative. This approach has the potential to make valuation reports more engaging and relatable to clients, ultimately enhancing their understanding and appreciation of the properties being valued.

All valuations are subject to risk and uncertainty. Therefore, the main issue that the valuation profession has continuously faced is how it can be reflected in the valuation process and communicated to its clients. Carsberg (Citation2002) and Mallinson (Citation1994) recognise the complexity of this issue and recommend the development of more practical approaches to expressing risk and uncertainty in valuation reports, particularly when there is insufficient comparable transaction evidence. To this end, the RICS Red Book and other International Appraisal and Valuation Manuals incorporate guidelines to effectively address and communicate risks and uncertainties in valuations. Furthermore, there is ongoing investigation to present an alternative approach for reporting risk and uncertainty in valuations based on techniques utilised within business applications (Adair & Hutchison, Citation2005; Joslin, Citation2005; Lorenz et al., Citation2006). For instance, Adair and Hutchison (Citation2005) provided insights into the utilisation of a risk-scoring system as a method for reporting risk within property valuations. The authors argue that employing a risk-scoring system offers a suitable approach to address this issue as it can be easily comprehended and communicated to external parties. To complement these efforts, this study argues for the use of storytelling as a tool for assessing and communicating risk and uncertainty in narrative valuation reports. Specifically, storytelling can be used to contextualise and explain to clients the risk and uncertainty surrounding the various valuation inputs in a more accessible and meaningful way. By weaving risk and uncertainty factors into a narrative, valuers can help clients understand their potential implications and make informed decisions based on a deeper comprehension of the risks involved.

Foundations of organizational storytelling

Given the storytelling imperative in narrative valuation reporting, valuation professionals must understand the foundations of organisational storytelling to effectively convey clear and powerful messages and expand others’ knowledge and understanding (Ravasi et al., Citation2019). The literature emphasises two essential aspects of storytelling based on organisational management perspectives: the art and craft of storytelling (Yoder-Wise & Kowalski, Citation2003). Each of these is unpacked as follows:

The art

Mastering the art of communicating dry data through storytelling provides an opportunity to engage and connect meaningfully with readers. Research suggests that people primarily make sense of data through stories (Knaflic, Citation2015). Where raw data drives people towards a questioning state, storytelling enables them to make sense of the data in a meaningful manner (Dykes, Citation2019). When hard data is integrated with a suitable style conducive to the audience it ‘connects the listeners’ (Yoder-Wise & Kowalski, Citation2003) and conveys the data using the art of storytelling. Through storytelling, valuers gain and retain trust in their reports and opinions. A skilful storyteller first uses relevant stories to establish their credibility and rapport with listeners. The listeners or audience receives the story based on the trust they place in the storyteller (Mai & Akerson, Citation2003), making it vital for valuation storytellers to assess their reputation and credulity on a regular basis. Trusted storytellers can communicate their opinions successfully and consistently.

An efficient storyteller establishes rapport and credibility by showcasing their expertise through stories. The stories they share could be anything from sharing some market knowledge and its implications or how a specific asset-related story may have ramifications for the future. These rapport-building stories are generally shared after initial contact to give the listener a sense of who the storyteller is, and they make sense of the data and stories behind the assets.

High-quality stories do not simply inform them of communication (Dykes, Citation2019). While the goal of information is to ensure that the audience receives the message, the role of communication is to enable the reader to understand the meaning of the data (Dykes, Citation2019).

Information dissemination without persuasive communication is passive and unmemorable, and lacks clarity. Although numbers and data may be the primary determinants of valuation quality, the art used by the valuer to share a story is remembered. These stories, which are based on market information, past analysis, and future trends crafted through skilful storytelling, are remembered and enable listeners/readers to gain valuable insights. Over time, through consistent high-quality storytelling, the valuer can craft and retain their reputation as a trusted advisor.

The craft

While storytelling art creates a sense of rapport with the audience, fine-tuning the craft of valuating stories can be achieved through high-quality, flawless presentations and logical and relevant content. Essentially, exceptional valuations require effective storytelling. The craft of writing good valuation stories is produced through the ability to collect accurate data/content and narrate or present it in a flawless and professional way.

Organisational storytellers disseminate content in various ways. Content development and storytelling can be achieved using several methods. Organisational storytelling is not static, with a stringent beginning, middle, and end (Boje, Citation2011). Instead, this is considered an ongoing process. However, stories told or written at or about a certain time are limited by their boundaries (Beigi et al., Citation2019).

The boundaries of data or asset-based storytelling are determined by the data and time within which the asset is valued. The content of the story comes from assets and markets. However, the interpretation and writing of a story depends on the storyteller. There are various ways of crafting stories. One way to construct an effective story was explored by Dennehy (Citation1999), who suggested that effective storytelling should consider five aspects.

Establishing the setting: In this phase, the storyteller describes the context, environment, players, and time in which the story occurs. Within a valuation story, this section includes the physical details of the asset, the market environment within which an asset is being valued, and the parties that may be interested in a particular valuation story.

Building the plot: Using data, the valuation story builds on the current state of the asset, highlights prospective successes, and provides warnings and predictions of market volatility.

Resolving the crisis: The climax explains the key takeaway from the story. The outcomes can be predictable, but may not be volatile and unpredictable. In valuation reports, the unpredictable may cause the client to question the valuer’s intent, but the craft of storytelling enables the valuer to turn the climax in their favour by presenting and explaining fair informed assessments in an interesting and simple manner that averts or resolves a crisis.

Describing the lessons learned: In this section, the valuation storyteller reiterates the core message and reasons for these results. While the valuation outcome may be obvious now, there is always more to the story. Some clients may require that the value be stated explicitly. For example, a client may perceive the value of their asset as XXX, but the valuer may observe a reduction in asset value due to unexpected market fluctuations. A mature audience may be able to read between lines, but others may need key lessons to spell it out.

Explaining how the characters change: The moral or takeaway from the story must not only include a final figure, but also how and why the figure was reached, and what changes the clients could make into an asset to realise different outcomes.

The integration

The art and craft of organisational storytelling creates a foundation for a good story. However, to make a story great, it is important to combine art and craft to complete the story. Where the art of storytelling creates a connection through persuasive communication of the central focus of the story, the craft ensures that all relevant details are professionally explained and presented. Without integrating art and craft, the momentum, power, and impact of stories would be lost.

Methodology

This study adopts a social constructionist, interpretive approach that acknowledges storytelling as socially constructed based on shared meanings and interactions. As defined by Beigi et al. (Citation2019), organisational storytelling is ‘an ongoing process of narrative sensemaking … and meaning construction … among and between the members of an organization to understand the past, share the present and shape the future’ ’(p.449). This definition highlights the dynamic nature of storytelling, emphasising the need for continuous understanding and adaptation of stories. It recognises that storytelling is not a static practice, but a fluid and evolving process. The qualitative stance taken by organisational research, as advocated by Alvesson and Karreman (Citation2000), challenges the positivist assumption that meaning creation is absolute. Instead, it acknowledges that the meaning behind the data is co-created by the storyteller, reader/listener, and the contextual environment. This perspective encourages writers to take responsibility for their role as storytellers and recognise the inherent subjectivity and influence they bring to the narrative (Horton et al., 2010).

As the study was designed to obtain a perspective that was different from the traditional positivist lenses used to understand property valuation (Amidu et al., Citation2021), it used social constructivist grounded theory. The use of this lens enables researchers to phenomenologically capture participant consciousness through their lived experiences (Merleau-Ponty, Citation2012), and allows for multiple realities (Golafshani, Citation2015). As the intent of the research was to generate theory and not to verify the existing theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017), this epistemology and methodology were considered the most effective methods to explore the objectives of this study, that is, to explore how practising valuers successfully implement storytelling in narrative valuation reports.

Participants were selected using purposive (Palys, Citation2008) or non-probability sampling techniques (Duignan, Citation2016), as the objective of the research was to access information from knowledgeable qualified valuers’ storytelling perspectives. Because the purpose of this study was not to obtain a population-based representation, theoretical sampling (Breckenridge & Jones, Citation2009; Charmaz, Citation2006; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) was used because the targeted participants were considered to provide relevant information that enabled the theory-building process (Miles et al., Citation2014). Interviewees were chosen until theoretical saturation was reached (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). In this study, theoretical saturation was not considered to be where no new information was being presented as there is always new perspectives that may arise, but one where a pragmatic saturation, i.e. the point where ‘emergent conceptual models and theoretical explanations’ (Low, Citation2019, p. 136), became evident.

Potential participants were approached and snowballing was utilised (Law, Citation2016; Rogers et al., Citation2013), where participants were asked to recommend other suitable participants. The University of Auckland Ethics Protocol (Committee, 2017) was used to ensure anonymity. The 19 valuers listed in were interviewed within the methodological frameworks and strategies. Of the participants, 78.9% were male. All valuers were registered and most had a bachelor’s degree (89.5%). More than half (52.6%) of the interviewees worked in a multidisciplinary property company (i.e. offering more than valuation services), while the remaining valuers worked in a private valuation practice. At the time of the interviews, most valuers (73.7%) had extensive knowledge of the valuation industry in New Zealand, with post-registration work experience of at least 10 years.

Table 1. Interview participants.

As this study aimed to explore the research question from the perspective of participants lived experiences (Boden & Eatough, Citation2014), data were collected through unstructured, one-to-one interviews based on open-ended questions. The unstructured nature of the questions enabled participants to share their stories, and the researchers explored, generated, and understood new perspectives (Gudkova, Citation2017). Based on the participants’ stories, probing questions enabled the researchers to understand the similarities and differences between the participants.

The data analysis commenced after each interview. Each interview was audiotaped with permission from the participants and transcribed as soon as it was complete. As qualitative research is emergent and dynamic (Merriam, Citation2016), analysing the data after each interview enabled the researchers to find recurring themes from each interview, which were then used to probe questions for future interviews. All the researchers independently coded the first three interview transcripts and developed a coding scheme. This scheme guided the coding process, which was updated regularly as new themes emerged.

Each interview was coded independently using within-case analysis and then collectively compared and differentiated with other interviews using across-case analysis (Gaudet & Robert, Citation2018). This dual-coding enabled researchers to identify themes unique to the individual and recurring themes highlighted by most participants (Miles et al., Citation2014).

Findings

The interviews in this study were designed primarily to understand valuation quality, conceptualised as a social system of shared meanings, symbols, perspectives, and interactions that are influential in undertaking a quality valuation in practice. What was evident, however, was how valuation quality was closely dependent on the sources used by the valuers to gather data and information (story collection), and the way in which they shared the story (storytelling). The following comments show where the valuers specifically mentioned storytelling:

… the way in which it’s communicated via the report, taking a client through, or the reader through, you know, the process, the thinking, the story around how you’ve come to your conclusions. (Valuer 1)

The answer to a valuation quality is to tell the right story, tell the client the story about the property and the valuation, then they do not come back and have to ask you a lot of questions. (Valuer 17)

The story really, so I want everything to tie in, yeah, so there’s no point having all this beautiful information, and this figure, and then nothing piecing it together. (Valuer 15)

It’s all about a story and you’ve got to take the reader on a journey of the story. (valuer 12)

This unexpected finding prompted researchers to consider value added by gaining a better understanding of the essential principles of high-quality valuation stories and crafting successful valuation storytelling, as discussed below.

High-quality valuation stories

Accurate narratives

The valuers interviewed in this study emphasised the importance of information accuracy in enhancing valuation reporting quality. Although valuation accuracy is commonly associated with the differences between valuations and the subsequent sale prices of properties transacted in the marketplace (Boyd & Irons, Citation2002; Crosby et al., Citation1998), participants’ perspectives diverge from this conventional view. They contended that a well-executed valuation revolves around the ‘art of comparison’ (Valuer 19) ‘at the time of the valuation’ (Valuer 3) and should not solely depend on the final sale figure, instead relies on whether ‘it can be clearly understood how the valuer arrived at his or her opinion’ (Valuer 10). Accuracy exceeded the figure and demonstrated the validity, reliability, and logical reasoning underlying valuation. The participants’ comments further elucidated this viewpoint.

A client will think a quality valuation is getting their number, but there is the service element, absolutely. From our perspective a quality valuation is one that has good rationale, is logical, well thought out and gets to a conclusion that makes a lot of sense and is accurate, defendable, and not going to get us sued. (Valuer 1),

The comments above are examples of valuers’ perceptions of what accuracy means or should mean in their role as providers of ‘independent and reliable advice as to how much they should lend effectively, or what the basis of their lending should be. So, in terms of quality, I’d say accuracy is the main one and you know, making sure that the report is fit for purpose’ (Valuer 5). Hence, a commendable valuation narrative presents a coherent and logical account that substantiates the valuer’s informed opinion. Ensuring validity and reliability, which are crucial for bolstering accuracy, requires employing verified information sources and referencing them to enhance data credibility.

One of the key aspects of accuracy is the ability to test available information for accuracy in the valuation process. The interviewees suggested that access to accurate information was difficult in an environment in which business interests prevented free and transparent information. This “secrecy (Valuer 3) can hinder the accuracy. The valuers explain:

There is a feeling that confidentiality is the biggest challenge in the market. One of the biggest challenges in the market now is getting information … because people are shrouding things in secrecy and hiding things. (Valuer 3)

And there is a lot of confidentiality now and that does make things a little hard. And sometimes, especially with shopping centres you have to rely on another valuer’s sales analysis of a shopping centre. Because they are bound by strict confidentiality, and they cannot give you the tenancy schedule. (Valuer 8)

With accurate information that was more difficult to access, interviewees suggested that it was essential to implement a process that ensured the validity and accuracy of the data. One valuer (Valuer 10) described the existence of a ‘verified’ button in their company’s database, which, when selected, provided a wealth of information.

A critical part of a valuer and a valuation is how accurate is their data, and how well have they analysed it? So, for example at … our database we set up, there was a very important button called verified and unverified. And if the verified button is hit in the database there is a whole raft of information that sits in behind that database printout you can access. (Valuer 10)

There is an emphasis on the need to validate information, cautioning against relying solely on unverified sources, such as newspapers or third-party outlets. Ensuring the accuracy of information requires valuers to prioritise the use of high-quality and reliable sources and appropriately cite them to enhance the trustworthiness of their data.

The interviewees were acutely aware of the direct correlation between accuracy and trustworthiness. Trustworthiness entails thoroughness, consideration of the data, and other market factors. A comprehensive valuation narrative encompasses the physical aspects of the property and its surroundings and an evaluation of its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. A valuer (Valuer 4) emphasised the significance of conducting the SWOT analysis, which involves the following:

… looking at what the good aspects are, I guess, of the property, what are the threats to the property, any opportunities that you can see with the property. And probably just considering all angles that may affect the property. (Valuer 4)

Considering that valuation represents an informed opinion at a given point in time, the findings underscore the need for valuers to critically evaluate their assumptions. It is crucial to avoid making assumptions that deviate significantly from the market expectations. Valuers should be mindful of the subjective nature of valuation and acknowledge it as an opinion of the value that falls within the range of opinions expressed by participants (Valuers 7, 9, and 15). However, these opinions should be supported by evidence derived from multiple benchmark points through triangulation (Valuers 8,9,10) to arrive at the final informed opinion (Valuer 6). Another valuer (Valuer 3) elaborates on the challenges involved in making an informed opinion on what property could sell. They state that, while the valuation is accurate,

… … . Whereas its proximity to an eventual sale price or its accuracy happens after a period of time, after the marketing etc. And often when you are looking at a valuation you do not really know … … … . You would expect that if a valuer has done their job thoroughly and produced a quality valuation and investigated the market and there are sales that are comparable then the determination of a figure which is within a reasonable bound of accuracy should not be that difficult to come up with. (Valuer 3)

In summary, accurate valuation narratives acknowledge subjective components as opinions of the values within this range. Nonetheless, these narratives are grounded in evidence derived from multiple benchmark points, triangulation, and the meticulous consideration of various market factors.

Balanced stories

The findings of this study demonstrate that compelling valuation narratives require a delicate balance and is not an ‘exact science’ (Valuers 7,10). Just as a skilled storyteller crafts a coherent storyline while incorporating twists and plots, a professional valuation storyteller must balance complex data, informed judgements, technical knowledge, and practical experiences. One participant explained this as follows.

… for the evidence that we consider, we’d go through and say right, well this property’s superior for these reasons, and inferior for these reasons. And it might be a better location, but it’s got a higher risk profile with the tenancies that it has … it’s about weighing all those things up and saying on balance, you know, all these things considered, how does that relate to the property that we’re valuing … it’s a depth of thought and understanding in terms of the market. (Valuer 1)

Here, the valuer explains how they weigh all evidence prior to making it informed and balanced. They suggest that practical experience enables valuers to gain a sense of intuition as they shift through information. One value explains this as follows.

… it’s the ability to override the information rather than just take everything at face value. But that’s just an experience and gut feel thing. I wouldn’t expect a student out of university to know what’s right and what’s wrong. That just takes years to get comfortable with. (Valuer 5)

Balance, in this context, seems to be the capability of making judgement calls based on evidence and “gut feel and understanding the market’ (Valuer 1). Furthermore, valuers must navigate the expectations of diverse readers with varying degrees of understanding of the valuation process, making it pertinent for valuers to find a balance between complexity and simplicity. One participant explained this balance as follows.

… this is where it is a bit challenging for valuers. We are heavily involved in these things daily, so we have a very good understanding of the process and what we’re doing, probably sometimes where we fall down a little bit is that as a result of that we forget that the reader doesn’t deal with this on a daily basis necessarily… And it is the challenge in that you want to simplify it, but you do need to be careful about oversimplifying. (Valuer 7)

A balance is crucial when crafting valuation narratives for different stakeholders. As indicated in the above comment, this study’s valuers acknowledged the varying expectations of stakeholders such as banks, institutional investors, developers, and other clients. They emphasised the need to manage these expectations. Building on the existing literature (P. W. Klamer, Citation2021; Levy & Schuck, Citation2005), this study highlights the need for valuation storytellers to strike a balance between satisfying customers and asserting an independent and unbiased perspective.

Although all valuers agreed that balancing multiple stakeholder priorities was challenging, their approaches to achieving balance varied, A valuer (Valuer 9) pointed out that while they cannot always, please everyone, they consistently aim to maintain balance through a feedback mechanism:

… We are not here to please all people all the time. But the balance is more around if we are applying things consistently through the middle, we have the bankers on one side and the owners on the other, how are they reacting to those numbers? And then checking that back against similar sales evidence in the market the whole time. (Valuer 9)

While the valuers seemed to be pride in themselves as unbiased and balanced professionals, as resonating from the interviews, the reason for striving for balance was also a matter of promoting business continuity. Balance or evidence is essential for protecting firms from potential lawsuits. Explaining this reasoning, the participant explained:

We are here to provide independent quality advice for the reliant parties … which is the instructing client, but it is the bank as well. Often, it is the person, it is their money at the end of the day … so it is just a big, big balancing act. But the bias was always in favour of protecting us really, because if we get it wrong then we get sued … So, we cannot afford it, (Valuer 5)

This perspective emphasises the significant challenge posed by client satisfaction and underscores the necessity of balanced valuation stories for their existence.

Clear comprehensive communications

The significance of presenting valuation narratives with clarity, readability, and logical structure has emerged as a fundamental factor influencing the quality of these stories. From the interviews, clear narratives were characterised by an optimal amount of information and striking a balance between comprehensiveness and conciseness. These narratives facilitate a logical and coherent flow, ensuring they ‘made sense’ to the readers (Valuer 8; Valuer 2).

The concept of clear communication in storytelling extends beyond raw content and encompasses the style and craftsmanship of the narrative. Contrary to previous assumptions that valuers primarily serve as experts in property data (Klamer et al., Citation2020), today’s valuers are skilled factual storytellers who guide readers through reports and conclusions. Two of the interviewees underscore this point as follows clear valuation reports are ‘easier to read, they are more logically set out’ (Valuer 1), and links ‘logically back to that answer…being concise in answering it so that the user can follow that report’ (Valuer 2).

Clarity is essential for leading the reader on a journey, presenting relevant information, data, and components of the subject property while highlighting how they compare it with other pertinent properties before offering an informed opinion or value (Valuer 5). One interviewee compared valuation to flying a plane, which required stringent and clear processes with checks and balances.

Well, valuation is no different, you need to have a very structured process to go through. And the valuation reports basically mirror that process, and that’s how they’ve evolved to take you through this journey of a valuation. (Valuer 10)

Being clear of the purpose, destination, and setting clear signposts were deemed necessary. However, there was also an emphasis on eliminating ‘conscious or unconscious bias’. In other words, clarity can be achieved by communicating the processes and logic used in valuation. One interviewee stated the following.

Making comments on the relevance of the comparability of each of your sales in relation to your subject. So, if you can drill down to that level and then communicate that reasonably well within the body of your report then it’s going to be clear to the reader as to your logic. The other aspect is clear communication in terms of your methodology and your approaches. (Valuer 7)

Clear communication also entails the ability of a discerning storyteller to omit irrelevant, outdated, or unimportant details. Interview participants pointed out that readers become confused when valuation stories contain irrelevant information as they detract from understanding how the valuer arrived at their conclusions. They suggested that clients prefer a concise report of 10 pages rather than a lengthy report of 50 pages so long that the concise version effectively conveys the necessary information.

Deep data driven stories

The findings of this study indicate that good valuation stories go beyond mere data comparisons. These stories incorporate external market influences and historical trends, and effectively integrate them into valuation narratives. Valuation storytellers succinctly craft these complex narratives with an understanding of the valuation theories and technical expertise.

The acquisition of deep data-driven stories is facilitated through various factors, including industry experience, access to current and reliable data, staying abreast of current affairs, engaging in communication with peers and experts, participating in industry training, possessing the ability to process complex information, and recognising the diverse priorities of stakeholders. One participant elucidated that this was a matter of ‘depth of thought and understanding’ of the market.

… sound understanding of principles and a very strong market knowledge … you tend to find individuals who really are experienced and know their marketplace with regards to transactional evidence, and what’s happening and sometimes what’s not happening. And then overlaid with that is a really sound, strong technical knowledge of the toolkit, I guess the relevant methodologies and how and when to apply them …. (Valuer 9)

Deep knowledge, as seen in the comment above, transcends the theoretical comprehension of data as it encompasses an awareness of market dynamics, the identity of buyers in the market, and the driving forces behind their decisions A professional valuation storyteller thus consistently considers the delicate balance between supply and demand, market fluctuations, key market participants, their assets, and priorities before concluding their narrative.

Enabling multimodal tools

The adoption of diverse media formats such as text, images, and videos has gained significant traction in organisations, particularly in marketing and communication (Nesteruk, Citation2015). In this study, interviewees expressed that incorporating these concepts into property valuation stories is a means of enhancing the quality of such narratives. Owing to time constraints, stakeholders prefer reports that feature explicit and high-quality textual content including graphs, illustrations, and other visual elements. Time limitations and the use of smaller devices such as mobile phones or tablets have necessitated a shift to newer ways of presenting complex information. As one interviewee put it, people often only ‘just flick’ through the document.

the report must be less wordy, just hits on key points that are material to a valuation, and are a bit more analytical as well, so they have a few more graphs, a few more pictures, and things like that. (Valuer 6)

…a better layout, modern, very keeping with the [company] image…more graphs, people love graphs, they love illustrations, they love maps, they love photos… (Valuer 8)

While the valuers stressed the need for the industry to embrace multimodal tools, the reasoning for using multimodal tools, including visuals, should not be cosmetic but strategically applied to pass meaningful and in-depth information. Furthermore, discussions were held regarding the use of technology, such as geo-mapping, to understand, track, and communicate the valuation stories. Some participants described how they adopted software customisation to cater to their individual companies’ needs.

Flawless reports

Creating flawless and convincing reports is a hallmark of knowledge-based professionals’ quality. However, many professionals struggle to achieve this proficiency level (Winner, Citation2013). The findings suggest that although the information may be accurate, the way it is presented determines the quality of the valuation and whether it is convincing the reader.

The interview participants noted that there was room for improvement in the quality of valuations currently presented to the market. For instance, a participant described the ‘calculation errors’ often presented in valuation reports as follows:

I have seen one from a firm where, instead of putting three percent per annum growth into the cash flow, they put 300 percent per annum growth. So, a $50,000 shop rent went from fifty grand to 1.5 million in 10 years’ time, and then capitalized that out … . poor quality valuations lack information, they lack rationale, they make leaps … there’s no connection between the evidence and the conclusions. There is no stepping the reader through the process … It can have a huge amount of information on the physical nature of the building but very lacking in understanding of the investment market for example. (Valuer 1)

These comments suggest that valuation stories challenging to read tend to confuse readers and fail to persuade them. Poorly laid out reports or grammatical or calculation mistakes undermine the credibility of such reports, leading clients and stakeholders to search for potential weaknesses. This finding confirms existing research that suggests that, while showcasing analytical skills is essential, how stories are shared also plays a crucial role in establishing credibility (Petelin, Citation2021). Valuers perceive the need to invest time and effort in crafting thorough, logical, and error-free narratives without room for factual, grammatical, or punctuation errors.

Skilled valuers recognise the importance of guiding readers logically through the valuation process, enabling them to reach the same conclusion. It is crucial to remember that while the valuers are ‘heavily involved in these things on a daily basis, and so we have a very good understanding of the process and what we’re doing … we forget that the reader doesn’t deal with this on a daily basis necessarily’ and therefore may not possess the same level of familiarity with valuation concepts (valuer 7).

Great relationships

This study highlights the roles of trust, reputation, and effective communication in fostering positive relationships between clients and stakeholders. Valuation stories extend beyond written reports and verbal communications. The interviewed valuers emphasised that establishing solid relationships with clients and other stakeholders is a prerequisite for how valuation stories are received. The consistent delivery of high-quality stories fosters trust in the valuer’s narrative (Karlgaard, Citation2014). One interviewee explained that banking clients often evaluate valuation stories based on their trust in the individual, which is shaped by their past experiences and knowledge of their track records. The reputation gained by consistently producing high-quality stories influences the client’s perception of the valuer’s work.

In addition, interviewees talked about the importance of understanding clients’ needs to ensure consistent relationships and reputation. A senior valuer interviewed stated the following.

Some of them think it is about producing a big voluminous report, which just drives me insane … It is just, gibberish mostly. The clients get it, and they go aargh, look at this massive pile of paper, I have paid for this 10 thousand=word report. I do not even like the number at the end, I cannot even get there, I cannot understand it. (Valuer 15)

Some interviewees suggested that a better approach would be to provide clear succinct reports and follow up with verbal communication where necessary. As one of the interviewees puts it: ‘It’s essential to always have an open phone policy, any valuation we do, we’re happy to take a phone call on it from a client, or a bank or whoever the end reader might be, thereby clarifying doubts and retaining relationships’ (Valuer 1). In addition, strong relationships with other valuers and professionals in the market are said to be an important part of accessing relevant information, especially in commercial valuations. As one interviewee pointed out, a lot of information is either tightly held or it is privately held, and so not readily available unless there is a reasonable level of relationships with certain suppliers. The interviewees suggested that they invested significant time and effort into cultivating these relationships.

It is like a bartering system, it gets a bit exhausting, but then you just have to get good relationships with other valuers. (valuer 8)

These findings highlight the importance of establishing strong relationships between clients and stakeholders in valuation stories. Trust, reputation, and regular communication are pivotal in ensuring the acceptance and understanding of valuation narratives. By consistently delivering high-quality stories and maintaining open lines of communication, valuers can build strong relationships that enhance their reception of and perception of their work. Effective communication enables valuers to address potential conflicts, provide explanations, and foster clarity in the valuation process.

Successful valuation storytelling

While existing research emphasises that professional judgement, attention to detail, honesty and integrity, diligence, independence, objectivity, and specialised knowledge are essential for providing valuation services (Amidu & Boyd, Citation2018), this study sheds light on valuers’ perspectives on translating these intangible characteristics into high-quality, written, and presented valuation stories.

Valuers emphasised the importance of showcasing their valuation skills through the tangible medium of well-crafted stories. While analytical skills are a prerequisite for valuers, participants highlighted other skills that were not readily observable. Valuers believe that an excessive focus on analytical reasoning without considering intuition and gut instincts could pose challenges (Valuer 4). Valuers must balance analytical thinking and incorporate their gut feelings into storytelling to produce convincing narratives. One senior valuer explained the following.

You know, it is one thing to be able to run the number, it is another thing to be able to report your thinking and tell that story. Because part of a quality valuation is about being able to explain the rationale to whoever those stakeholders are … and they should basically be able to see exactly your thought process as to why and what you’ve done, as if you’re in an investor’s shoes or a banker’s shoes. But the big piece in terms of, I guess it’s the toolkit, the technical side and how to write a good report and what to put in it, but the bit in the middle is actually making the decision on the answer … the actual, the verdict, the answer at the end, you know, it is that there’s a certain amount of intuition and gut feel that makes a quality valuer and a quality valuation. And that is that understanding of those external factors of who is in the marketplace, different little subcategories, and all the nuances that break the market down into a much more complex beast that certain parts of the market, certain sectors, certain price points may be running very strong while other ones aren’t. (Valuer 9)

Finding this balance between analytical skills and judgement and gut feel can take time and cannot always be taught because ‘you have it or you don’t’ (Valuer 1), new valuers who sometimes were ‘quite narrow focused … It is just like tunnel vision’, (Valuer 4) can use strategies in data storytelling to convey their message clearly, thoroughly, and efficiently.

Successful valuation storytellers possess unique skills that extend beyond analytical reasoning. Translating intangible characteristics into high-quality stories is essential to effectively communicate valuation insights. Valuation students must equip themselves with the art of storytelling, relationship-building skills, and the capacity to integrate their intuition while maintaining objectivity. Attention to detail and commitment to presenting balanced and impartial narratives is imperative to avoid costly mistakes and to maintain a professional reputation. Understanding these characteristics and their impact on valuation storytelling is vital to advancing valuation practices and enhancing the quality of valuation services.

Discussion and implications

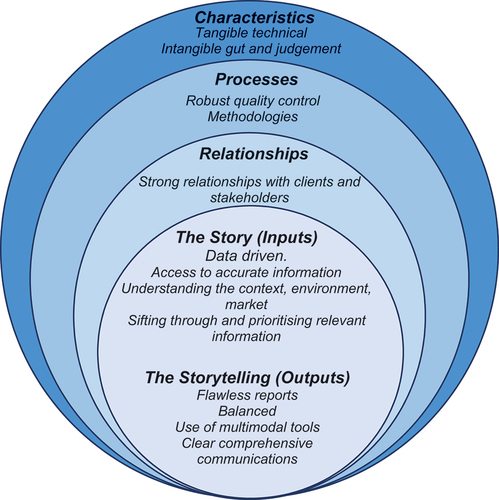

In the context of professional practice, storytelling is increasingly being recognised as a crucial tool for effective communication with diverse stakeholders (Beattie & Davison, Citation2015). The findings of this study contribute to positioning storytelling as a central element in effective quality valuation reporting behaviour. Previous work by Amidu et al. (Citation2021) defined valuation quality as a complex and context-specific concept that requires professionalism, effective communication, accurate reporting, and regulatory compliance. This study uncovered six essential components of valuation storytelling, presented in , along with a comprehensive list of guidelines to help create a powerful narrative valuation report. The checklist encompasses aspects of the valuation process, from gathering and analysing data to presenting it in a compelling manner.

Table 2. Checklist of essential guides for writing effective narrative valuation report.

The importance of accuracy in valuation narratives extends beyond the difference between valuation and sales price. Valuers emphasise the ‘art of comparison’ and the need for clear, logical, and defendable rationales. Additionally, this study underscores the challenges of accessing accurate information due to confidentiality and the need for a process to ensure data validity and accuracy. Furthermore, the findings emphasise the need for balanced narratives that weigh complex data, informed judgements, technical knowledge, and practical experiences. Clear and comprehensive communication is essential for guiding the reader through the valuation process, whereas deep data-driven stories incorporate external market influence and historical trends. This study also emphasises the adoption of multimodal tools and the need for flawless reports to present information clearly and concisely. These essential principles for great valuation stories were cemented by strong relationships followed by robust processes throughout the course of the valuation.

Empirically, this study shows that valuers need to understand, analyse, and communicate the reasons behind numbers. Valuers emphasised the need to explain the rationale behind their valuations and to tell a compelling story that allows stakeholders to understand the thought process behind the valuation. This aligns with Amidu and Boyd’s (Citation2018) emphasis on the importance of professional judgement, attention to detail, honesty and integrity, diligence, independence, objectivity, and specialised knowledge in providing valuation services. Furthermore, this study highlights the need for valuers to balance analytical thinking with intuition and gut feelings in order to produce convincing narratives. This aligns with the assertion made by a senior valuer in the study, who emphasised the role of intuition and gut feel in making a quality valuer and a quality valuation. This study suggests that finding a balance between analytical skills, judgement, and gut feel can take time and cannot always be taught, indicating that it is a skill that may be inherent in some individuals.

Based on these findings, this study proposes conceptualising valuation storytelling and emphasises that the art and craft of valuation data storytelling involve prioritising both the content collection for the story (inputs) and the telling of the story (outputs), as conceptualised in .

depicts the conceptualisation of the valuation process through three outer rings, each representing essential aspects before, during, and after the valuation process. The outermost ring, ‘Characteristics’, emphasises the traits necessary for a successful valuer. Valuers must possess both tangible technical and analytical skills as well as intangible intuition to make informed judgements. These attributes encompass the art of storytelling, which involves the skill of comprehending the essence of the property, and the craft of storytelling, which involves weaving findings into a meaningful and engaging narrative. The subsequent ring, ‘Processes’, underscores the importance of robust quality control at all stages of the valuation process, including data collection, input, methodologies for analysis, and data presentation. The final ring, ‘Relationships’, emphasises the need for valuers to establish trustworthy, long-term relationships with various industry stakeholders such as clients, banks, investors, suppliers, other valuers, real estate agents, and other professionals.

The context within these rings signifies the stage of high-quality data evaluation. The inputs, referred to as the ‘Story’, encompass the data collected, such as the physical attributes of the property, market data, comparable properties, environmental factors, market conditions, contextual variables, and other relevant parameters, which collectively establish the foundation for the narrative. Consequently, subject property assumes the pivotal role of the central character in the story. The art of data storytelling equips the valuer with the ability to discern and incorporate pertinent information to interpret data comprehensively.

However, the process of sharing high-quality data stories extends beyond mere collection. It involves the strategic utilisation of relevant data to construct a coherent and logical narrative rather than presenting an exhaustive summary of all collected content (Knaflic, Citation2019). This approach is in line with expert views on high-quality storytelling, emphasising the significance of presenting descriptive analysis rather than simply showcasing all gathered data during exploration (Knaflic, Citation2019). Therefore, it is essential to place equal emphasis on how the story is told and its output.

In recent years, the use of storytelling techniques to present data in valuation reports has attracted increasing attention. Although storytelling has been a traditional method of communication since ancient times, its application in presenting dry data in valuation reports has the potential to enhance the persuasiveness and relevance of information. A professional valuation story should be accurate, based on facts, and demonstrate a clear understanding of the market (Amidu et al., Citation2021). This study proposes that incorporating data storytelling theories into the framing of valuation reports can simplify complex data and methodologies, thereby making information more accessible and relevant to stakeholders. By presenting data-driven insights through narratives, valuers can bridge the gap between technical analysis and stakeholder comprehension.

Presenting compelling valuation stories can involve utilising Nesteruk’s (Citation2015) multimodal and digital tools such as geo-mapping, photos, illustrations, maps, and videos. The findings of this study underscore the need for valuers to possess the skills and tools necessary to create visually appealing, contextually relevant stories. These implications extend to institutions that offer valuation training and education. Sharp and Brumberger (Citation2013) advocate storytelling and communication courses in business education, and this study further supports the relevance of such training in property valuation.

While traditional valuation education and expertise have primarily emphasised analytical valuation skills (Amidu, Citation2011), this study underscores the significance of presenting valuation stories in an accurate, balanced, engaging, and straightforward manner. For valuation stories, it is crucial to engage clients effectively and persuade them of the fairness of the results. Furthermore, the flawless grammatical and structural qualities of the report contribute to its credibility, highlighting the essential nature of professional storytelling and communication skills of valuers. Therefore, the integration of data collection skills, information organisation, and the development of compelling narratives should be integral components of educational curricula in property valuation.

This study proposes that the valuation industry actively integrates various ways of telling stories into its practices and processes. Valuers can enhance the quality and effectiveness of their valuation stories by emphasising clear and comprehensive communication and delivering deep market knowledge. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the importance of storytelling in valuation and underscore the need for valuers to be skilled storytellers who can create compelling narratives that resonate with clients and stakeholders.

Conclusion

The manner in which stories and data are presented plays a crucial role in demonstrating the quality of property valuation. While numbers and data are essential for estimating the financial value of an asset, stories aid readers in comprehending the rationale behind numbers. Long after the numbers and data have faded from memory, valuation stories continue to shape and form an integral part of the narrative, not only of the asset being valued, but also of the environment in which the asset is situated.

The findings are not only pertinent for creating engaging stories but also for establishing a benchmark for high-quality stories and enhancing the reputation of the valuation profession. Therefore, valuers should not only dedicate their time to information collection and analytical processes, but also invest in enhancing their storytelling skills. It may be timely for valuation organisations to enlist the expertise of storytelling professionals who can assist valuers in crafting compelling and accurate, high-quality stories. In addition, professional valuation organisations should establish a story bank comprising practical guides and case studies on storytelling to assist valuers in effectively utilising and producing valuation stories. The significance of storytelling has implications for training and professional development in the valuation field. It may be necessary for students in property education to undertake mandatory courses in storytelling and business writing.

This study is limited in its focus on a single country and stakeholder, thereby presenting an opportunity for further research involving other stakeholders, such as clients, banks, property students, and trainers. While this study was conducted in New Zealand, there is an opportunity to conduct a multicountry study on how storytelling can be utilised as a tool in different cultures and contexts within professional service firms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, A., & Hutchison, N. E. (2005). The reporting of risk in real estate appraisal property risk scoring. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 23(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780510599467

- Alvesson, M., & Karreman, D. (2000). Varieties of discourse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis. Human Relations, 53(9), 1125–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700539002

- Amidu, A.-R. (2011). Research in valuation decision making processes: Educational insights and perspectives. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 14(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2011.12091685

- Amidu, A.-R., & Boyd, D. (2018). Expert problem-solving practice in commercial property valuation: an exploratory study. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 36(4), 366–382. https://doi.org/10.1108/jpif-05-2017-0037

- Amidu, A.-R., Levy, D., & Bolomope, M. (2021). Conceptualising valuation quality in practice: A valuer perspective. Journal of Property Research, 38(3), 213–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2021.1930108

- Appraisal Institute. (2020). The appraisal of real estate (15th Edition ed.).

- Beattie, V. & Davison, J. (2015). Accounting narratives: Storytelling, philosophising and quantification. Accounting and Business Research, 45(6–7), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2015.1081520

- Beigi, M., Callahan, J., & Michaelson, C. (2019). A critical plot twist: Changing characters and foreshadowing the future of organizational storytelling. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12203

- Blankenship, A. (1998). The appraisal writing handbook. Appraisal Institute.

- Boden, Z., & Eatough, V. (2014). Understanding more fully: a multimodal hermeneutic-phenomenological approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(2), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.853854

- Boje, D. M. (2011). Storytelling and the future of organizations: An antenarrative handbook (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203830642

- Boyd, T., & Irons, J. (2002). Valuation variance and negligence: The importance of reasonable care. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 8(2), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/14445921.2002.11104118

- Breckenridge, J., & Jones, D. (2009). Demystifying theoretical sampling in grounded theory research. Grounded Theory Review, 8(2), 113–126. https://www.groundedtheoryreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/GT-Review-Vol8-no2.pdf#page=64

- Bruce, T., McNair, L., & Whinnett, J. (2020). Putting storytelling at the heart of early childhood practice: A reflective guide for early years practitioners. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429283369

- Carsberg, B. V. S. (2002). Carsberg report: Property valuation. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). The power of names. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 396–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241606286983

- Colwell, P., & Trefzger, J. (1992). Impact of regulation on appraisal quality. The Appraisal Journal (July), 6(3), 428–429. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/impact-regulation-on-appraisal-quality/docview/199917892/se-2

- Crosby, N. (2000). Valuation accuracy, variation, and bias in the context of standards and expectations. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 18(2), 130–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780010324240

- Crosby, N., Lavers, A., & Murdoch, J. (1998). Property valuation variation and the ‘margin’ of error in the UK. Journal of Property Research, 15(4), 305–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/095999198368310

- Crosby, N., Newell, G., Matysiak, G., French, N., & Rodney, B. (1997). Client perception of property investment valuation reports in the UK. Journal of Property Research, 14(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/095999197368744

- Dennehy, R. F. (1999). The executive as storyteller. Management Review, 88(3), 40–43. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/executive-as-storyteller/docview/206693086/se-2

- Dessart, L., & Pitardi, V. (2019). How stories generate consumer engagement: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 104, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.045

- Dotzour, M., & Le Compte, R. (1993). Lender perceptions of appraisal quality after FIRREA. The Appraisal Journal, (April), 61(2), 227–233. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/lender-perceptions-appraisal-quality-after-firrea/docview/199953821/se-2

- Drumm, M. (2013). The role of personal storytelling in practice. IRISS, Insights, No.23. http://www.iriss.org.uk/resources/role-personalstorytelling-practice.

- Duignan, J. (2016). Purposive sampling (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Dykes, B. (2019). Effective data storytelling - how to drive change with data, narrative, and visuals (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Fog, K. (2010). Storytelling branding in practice (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Gaudet, S., & Robert, D. (2018). A journey through qualitative research: From design to reporting. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529716733

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- Golafshani, N. (2015). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2003.1870

- Gudkova, S. (2017). Interviewing in qualitative research. In Qualitative methodologies in organisational studies (pp. 75–96). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65442-3_4

- Hardy, P., & Sumner, T. (Eds.). (2018). Cultivating compassion: How digital storytelling is transforming healthcare. Palgrave Macmillan.

- IVSC. (2022). International valuation standards 2022. International Valuation Standards Council.

- Jamissen, G., Hardy, P., Nordkvelle, Y., & Pleasants, H. (2017). Digital storytelling in higher education: International perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, P., & Comfort, D. (2018). Storytelling and sustainability reporting: An exploratory study of leading US retailers. Athens Journal of Business and Economics, 4(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajbe.4.2.2

- Joslin, A. (2005). An investigation into the expression of uncertainty in property valuations. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 23(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780510599476

- Karlgaard, R. (2014). The soft edge: Where great companies find lasting success. John Wiley & Sons.

- Klamer, P. W. (2021). Valuing the client or the property? An examination of client-related judgement bias in real estate valuation. Utrecht University. https://doi.org/10.33540/279

- Klamer, P., Gruis, V., & Bakker, C. (2020). The ideal type of valuer: Expert, service provider or reporter? an investigation into prevailing role types in commercial valuation. Property Management, 39(2), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/pm-03-2020-0019

- Knaflic, C. N. (2015). Storytelling with data: A data visualization guide for business professionals. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Knaflic, C. N. (2019). Storytelling with data let’s practice!. John Wiley & Sons.

- Knitter, R. (1995). 1994 survey of appraisal clients. The Appraisal Journal, (April), 63(2), 213–219. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/1994-survey-appraisal-clients/docview/199922434/se-2

- Law, J. (2016). Snowball sampling. In a dictionary of business and management. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199684984.001.0001/acref-9780199684984-e-5949

- Levy, D., & Schuck, E. (2005). The influence of clients on valuations: The clients‘ perspective. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 23(2), 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780510584364

- Lorenz, D., Trück, S., & Lützkendorf, T. (2006). Addressing risk and uncertainty in property valuations: A viewpoint from Germany. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 24(5), 400–433. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635780610691904

- Low, J. (2019). A pragmatic definition of the concept of theoretical saturation. Sociological Focus, 52(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2018.1544514

- Lugmayr, A., Sutinen, E., Suhonen, J., Carolina Islas, S., Hlavacs, H., & Calkin Suero, M. (2017). Serious storytelling – a first definition and review. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 76(14), 15707–15733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-016-3865-5

- Mai, R., & Akerson, A. (2003). The leader as communicator: Strategies and tactics to build loyalty, focus effort, and spark creativity. AMACOM, American Management Association.

- Mallinson, M. (1994). Mallinson report: commercial property valuations. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors,

- Martin, D., Najib, M., Nowell, G., & Eni, S. (2011). Quality of valuation report in Malaysia. NAPREC, Valuation and Property Service Department, Ministry of Finance.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2012). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge.

- Merriam, S. B. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. A., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.