ABSTRACT

Understanding stroke survivor responses to attainable and unattainable goals is important so that rehabilitation staff can optimally support ongoing recovery and adaption. In this qualitative study, we aimed to investigate (i) stroke survivor's experiences of goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement in the first year after stroke and (ii) whether the Goal setting and Action Planning (G-AP) framework supported different pathways to goal attainment. In-depth interviews were conducted with eighteen stroke survivors’ to explore their experiences and views. Interview data were transcribed verbatim and analysed using a Framework approach to examine themes within and between participants. Stroke survivors reported that attaining personal goals enabled them to resume important activities, reclaim a sense of self and enhance emotional wellbeing. Experiences of goal-related setbacks and failure facilitated understanding and acceptance of limitations and informed adjustment of, or disengagement from, unattainable goals. Use of the G-AP framework supported stroke survivors to (i) identify personal goals, (ii) initiate and sustain goal pursuit, (iii) gauge progress and (iv) make informed decisions about continued goal pursuit, adjustment or disengagement. Stroke survivor recovery involves attainment of original and adjusted or alternative goals. The G-AP framework can support these different pathways to goal attainment.

Introduction

Stroke survivors have personal hopes for the future and goals they would like to achieve (The Stroke Association, Citation2012). However, many struggle to attain their goals in the first year after stroke (Brands, Stapert, Kohler, Wade, & van Heugten, Citation2015). This is not surprising given that stroke is a common cause of adult complex disability (Adamson, Beswick, & Ebrahim, Citation2004) and can result in a wide range of impairment, activity and participation restrictions (Paanalahti, Alt Murphy, Lundgren-Nilsson, & Sunnerhagen, Citation2014). The ongoing tension between stroke survivors’ hopes and goals and the unique array of stroke impairments challenging their function creates a complex, dynamic landscape in which their recovery journey unfolds.

The Goal setting and Action Planning (G-AP) framework guides patient centred goal setting practice in community stroke rehabilitation settings (Scobbie & Dixon, Citation2014; Scobbie, Dixon, & Wyke, Citation2009, Citation2011; Scobbie, McLean, Dixon, Duncan, & Wyke, Citation2013). Evidence and theory based, G-AP informs a collaborative approach between stroke survivors and staff to the setting and pursuit of rehabilitation goals. It has four key stages: (i) goal negotiation and setting, (ii) action planning and coping planning, (iii) action and (iv) appraisal, feedback and decision making. Stroke survivors personal goals, plans and appraisals are recorded in the stroke survivor held G-AP record (see Supplementary File 1).

Findings of an initial evaluation of G-AP in one setting, including eight stroke survivors and eight health professionals, suggested it showed promise as a useful, acceptable and feasible framework to guide goal setting practice (Scobbie et al., Citation2013). A novel finding reported within this study was staff concers about the impact of goal non-attainment on stroke survivors’ wellbeing. Stroke survivors did not report the same concerns. Although upsetting, stroke survivor accounts suggested that the experience of goal non-attainment helped them to understand, accept and adjust to their limitations. This finding exposed an under researched area in stroke rehabilitation research and practice.

Building on this research, we conducted a process evaluation of the G-AP framework in three community rehabilitation settings. We aimed to investigate staff views of its implementation and stroke survivors’ experiences of recovery and adaption to limitations. In this paper, we report on the latter of these two aims. Our specific research questions were: 1. What are stroke survivors’ experiences of goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement in the first year after stroke? 2. Does the G-AP framework support different pathways to goal attainment?

Methods

The standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) were used to inform the conduct and reporting of this study (O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, Citation2014).

Study design

Three Scottish community rehabilitation teams participated in the study from February to July 2014. Team members were trained how to use the G-AP framework in practice, including use of the G-AP record. G-AP was implemented with stroke survivors referred to the team within the study period. Full details of participating teams, training provided and implementation of the Goal setting and Action Planning framework from a staff perspective are reported elsewhere (Scobbie et al., Citationin preparation).

Ethical approval was obtained from the West of Scotland Research Ethics Service (ref no: 12/WS/0292) and University of Stirling School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Research Ethics Committee. NHS Fife and Lothian provided Research and Development approval. All stroke survivors provided informed written consent for the interview. Accessible versions of study information sheets and consent forms were available if required.

Participants

Stroke survivors referred to each team within the study period, with at least six weeks exposure to use of the G-AP, were eligible for recruitment. Those eligible were given a study information sheet, invitation letter, response sheet and stamped addressed envelope by a staff member. Information was provided about the aims of the study and researchers involved. Those returning response sheets were telephoned (LS) and given an opportunity to ask questions. Following this, an interview date, time and location was agreed. To reflect diversity within the stroke survivor population, we aimed to purposively sample (i) between 15 and 20 stroke survivors (ii) with even numbers of males and females (iii) representing a range of ages (iv) disability levels and (v) comorbidities.

Data collection

In-depth interviews with individual stroke survivors were conducted to gather insights relevant to the research questions. Interviews took place in the team base or the stroke survivor's own home, whichever was most convenient. With permission, all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The interview topic guide focused on experiences of goal related successes and setbacks and use of the G-AP framework (See Supplementary File 2). Stroke survivors were encouraged to refer to their G-AP record as a reminder of their personal goals, plans and appraisals. Field notes were taken following each interview to enhance reflexivity throughout the process. Case notes of interviewees were reviewed and relevant demographic information tabulated (see Supplementary file 3).

Data analysis

Interview data were analysed using the Framework approach (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994). This approach is widely used in health research (Gayle, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, Citation2013) and allows for the identification of novel and expected themes both within and between cases.

Interview data

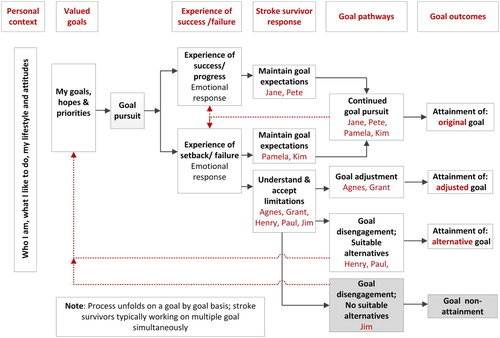

Transcripts were read, checked (with reference to original audio recordings) and anonymised [LS] to ensure accuracy and establish familiarization with the whole data set. Anonymised transcripts were imported into QSR-NVivo10 (QSR international Pty ltd, 2011) software to facilitate data management. Six interview transcripts were read, and codes applied, to identify broad expected and novel themes [LS]. The broad thematic framework was reviewed, with reference to extracted data, and agreed by the project team. It was then applied to a further 10 transcripts [LS]. Following this, data within each broad theme were reviewed and coded into sub themes [LS]. The developing thematic framework was then reviewed and further refined by checking data coded within themes and subthemes from five randomly selected transcripts (LS, ED). This process resulted in removing redundant sub-themes, merging those that overlapped and relabelling others to better reflect the data contained within them. The research team discussed and approved the final thematic framework (see ). The final thematic framework was applied to the two remaing transcripts to ensure data saturation had been achieved across all themes and sub-themes and that no further interviews were required. Finally, data were summarized into theme based data matrices, on a case by case basis, to enable further data analysis and interpretation.

Table 1. Final Thematic framework.

Case note data

Demographic and initial assessment data were extracted from each participant's case notes; pseudonyms were used to maintain anonymity. A Modified Rankin Scale (Banks & Marotta, Citation2007) was retrospectively applied to each participant to determine disability level. A descriptive summary of demographic information was included within each case on individual data matrices.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

LS (female) developed the G-AP framework during her PhD studies and was the principal investigator on this study. LS was trained in the use of the Framework approach and had used it successfully in a previous study (Scobbie et al., Citation2013). LS did not know participating teams or research participants prior to commencing the study. LS endeavoured to maintain a neutral stance through out the study. Reflexive diaries and field notes were completed following each interview. These were discussed within research team meetings to support an open, transparent and objective approach to data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Results

Participant characteristics

Eighteen stroke survivors, all within one year post stroke, provided informed consent for interview (see ). Duration of rehabilitation input at the time of interview ranged from two to 11 months. Participants included 10 men and eight women ranging from 28 to 85 (mean 64) years old. Slight to moderate-severe disability levels and a wide range of stroke related impairments were represented in the sample. Co-morbidities included previous stroke, diabetes, arthritis and mental health problems. The duration of interviews ranged from 50 to 90 minutes. None of those providing consent dropped out of the study.

Table 2. Stroke survivors included in the study.

Stroke survivors’ experiences of goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement

Four main themes captured how goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement featured in individual stroke survivors’ accounts: 1. identifying personal goals, 2. experience of success, 3. experience of setbacks and 4. gauging progress and making informed goal decisions.

Personal goals were informed by stroke survivors’ sense of who they were, activities that were important to them and their lifestyle and attitudes (personal context). Experiences of success and failure supported stroke survivors to gauge progress and make informed goal decisions. Attaining valued goals (experience of success) enabled stroke survivors to engage in important activities, reclaim a sense of self and enhance their emotional wellbeing. Of equal importance was the experience of goal related setbacks and failure. Although disappointing for some, this experience could facilitate a deeper understanding and acceptance of limitations which informed adaptive adjustments to, or disengagement from, goals judged too difficult to achieve.

In the following sections, themes and sub themes are reported within selected cases to illustrate how goal attainment, adjustment and disengagement featured within stroke survivors’ accounts.

Goal attainment

Many stroke survivors attained one or more of their original goals which enabled them to engage in highly valued activities, reclaim a sense of self and enhance their emotional wellbeing. All described important goal related successes (or steps) along the way that resulted in a positive emotional response and motivated continued goal pursuit (see Box 1).

Jane's goal: Taking her grandchild out for a walk in the pram.

“We went out on Saturday [with the pram] … it felt great. I just thought … this is normal. This is me walking down the road with my wee [small] grandson. I felt fabulous. I didn't think I was going to fall … it was just lovely the three of us out together – it was great!”

Themes: Experience of success

Sub-themes: Goal attainment; Emotional response

Jane viewed herself as someone who related well to children.

“ … they call me ‘mother earth’ cause all the kids come round me and I just love kids, and I thought this would be a big loss if I couldn't do that [spend time with children].”

Themes: Identifying personal goals

Sub-themes: Personal context; My goals, hopes and priorities

When asked if there had been important steps to achieving her goal, Jane said:

“Mm hmm, definitely in the physio [physiotherapy]. I had been on a sort of balance ball and I found that really quite difficult and then when I was going on it latterly there I thought ‘I’ve got this down pat [sic], I can do this no bother [easily]!’ So it was a day when I just thought ‘oh that's going great.’”

Theme: Experience of success

Sub-theme: Important steps; Emotional response.

Continued goal pursuit, even in the face of setbacks, was important when goals were still considered achievable or too important to adjust or disengage from. Emotional responses to set backs could include feeling frustrated or stupid; but determination to keep going and hope for a positive outcome were maintained (see Box 2).

Pamela's goal: To walk to the local supermarket by herself.

“I planned to go to [supermarket] on my own, I used to walk, I used to do an awful lot of walking, never got a bus or anything like that, always walking … and I said to B [husband] ‘right I’m going to try this on my own, to walk down [to the supermarket].”

Themes: Identifying personal goals

Sub-themes Personal context; My goals, hopes and priorities

“It was snowing, and I was just two minutes off of [the supermarket] if I’d of kept walking eh, and I says ‘no, go back Pamela, you can try another time’.”

Interviewer: How did that make you feel?

“It made me feel more determined … I just says ‘Pamela, just go back home, you’ve not [had] a defeat, try it another day’ and I did … and I did it!”

Theme: Experience of set back; Gauging progress and making informed decisions; Experience of success

Sub-theme: Emotional Response; Continued goal pursuit; Goal attainment

Kim's goal: To walk without using a stick.

“I always thought, ‘walking sticks are for old people, it's not for younger people’, so I really wanted to get to that goal [walking without the stick].”

Theme: Identifying personal goals

Sub-theme: Personal context; My goals, hopes and priorities

“I was with my mum [when I fell in the supermarket] and they wanted to get an ambulance, I was like ‘no you’re not getting an ambulance, no danger, I’ll get up myself in my own time, thanks very much but I don't need any assistance’. You just feel … for me I just feel stupid eh … your confidence is knocked, you feel like it's never ending.”

Themes: Experience of setback

Sub-theme: Emotional Response

“I drive for the goals [walking without a stick] because I want to get better and I drive because I want to get back to normality if you like.”

Themes: Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Continued goal pursuit

Goal adjustment

With one exception (Alexander), all stroke survivors described setbacks, or lack of progress in goal pursuit, that led them to adjust goals. This experience resulted in different emotional responses. Understanding and accepting limitations typically preceded adjustment of a valued goal. Achieving adjusted goals enabled stroke survivors to engage in important activities, reclaim a sense of self and enhance emotional wellbeing, albeit via a different route than originally planned (see Box 3).

Agnes’ goal: To live by herself following a period of living with her daughter.

“She [her daughter] was doing everything with me, everything for me, she was making my meals, she was dressing me, everything and I says ‘it's not right’, I’m too independent. So I says [sic] ‘no, I want to try living myself.’”

Themes: Identifying personal goals

Sub-themes: Personal context; My goals, hopes and priorities

Agnes was at home, but finding it difficult to reach her other goal of making a pot of home-made soup.

“Aye [yes], I’ve tried it [arm and hand exercises] and well we’ve been trying for a year so it's not working [her right arm] … I says ‘that's not going to work, so that's it’ cause … well, I was disappointed in a way but I says ‘oh well, I’m stuck with it.’”

Theme: Experience of setback; Gauging progress and making decisions

Sub-theme: Goals proving difficult to achieve; Understanding and accepting limitations; Emotional Response

Agnes adjusted her goal. Rather than prepare her own vegetables, she bought pre-cut vegetables and a soup maker instead.

“I’ll find a way to do it. It's not how I used to make soup, but it's better than nothing!”

Themes: Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Goal adjustment

Grant's goal: To resume his previous job working 60 hours per week.

“That's what I’ve done for the last 30 year [worked 60 hours per week] … I think it's what was built into me; it's how I’ve been taught … if you worked hard there was money to be made, and that's been engrained in me.”

Themes: Identifying personal goals

Sub-theme: Personal context, My goals, hopes and priorities

“I realised that that was never going to be my goal [working a 60 hour week] because when I went back, I was struggling to do eight hours, by the time sort of mid-afternoon came, I was tired and I knew I needed to go home.”

Themes: Experience of a setback; Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Goals proving difficult to achieve; Understanding and accepting limitations

When asked how he felt about having to adjust his goal, Grant said:

“When I found out what I was getting [paid] for like 37 hours it was quite manageable, I was happy with that. I knew physically and mentally I wasn't fit enough to do more.”

Theme: Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Understanding and accepting limitations; Emotional response; Goal adjustment

Goal disengagement

Limitations imposed by the stroke could render valued goals unachievable. Although disappointing, hope was maintained. Disengaging from unachievable goals, even on a temporary basis, enabled stroke survivors to redirect their efforts to other achievable goals. This was relatively straight forward for those who had alternative goals to pursue (see Box 4); but challenging for those who did not (see Box 5).

Henry's goal: To dress independently,

“It didn't get much better [his arm]. We used to pick up things up [during rehabilitation] and I would put it in a box and put it on my table and vice versa … never seemed to get much easier.”

Theme: Experience of setback/ failure; Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Goals proving difficult to achieve

“I came to the conclusion I wouldn't be able to do up buttons. I’ve still got a carer comes in in the morning and helps me get into the shower then puts my clothes on and she does the buttons … I wouldn't like that to be forever though.”

Themes: Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-themes: Understanding and accepting limitations; Goal disengagement; Emotional response

Henry continued to work on other goals including walking with a stick in the house and going out with his wife to the local shopping centre, both of which he achieved.

Paul's goal: To walk to the local bus stop.

“[I’m] now aware this goal is not realistic, given the distance involved. It is too far. It's about 400 metres [to the bus stop] and I really could not, even now, I could not walk 400 metres.”

Themes: Experience of setback/ failure; Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-themes: Goal proving difficult to achieve; Understanding and accepting limitations; Goal disengagement

Interviewer: “And were you disappointed when you realised you wouldn't be able to walk to the bus stop?”

Paul: “Oh yeah, I was disappointed. But in saying that, I wasn't devastated or anything like that. I’ve just accepted that that was the … that's the other thing I’m having to do, you know, is realise some of the limitations and having some acceptance of it, you know, that at this stage anyway – not saying forever – but at this stage there's certain things I can't do, I need to be realistic about that. I can't walk 400 metres to the bus stop so that's why we’ve revised that [goal] and that's why we’ve put in walking round the block three times a week.

Theme: Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-themes: Emotional response; Understanding and accepting limitations

Jim's goal: To get back to playing bowls once week.

“The physiotherapist had me with the stick, and was no good [walking with the stick]. I went across the floor [fell] with the stick once. You get really depressed at times. You know, you think about the person you were, and the person you now are. That's been very difficult. You’ve got to accept it. But, I’ll never play bowls again – I’ve resigned myself to that. I used to enter all the competitions.”

Themes: Experience of setback; Gauging progress and making informed decisions

Sub-theme: Goals proving difficult to achieve; Understanding and accepting limitations; Goal disengagement; Emotional response

Interviewer: Has it been difficult to come to terms with not being able to play bowls again?

Jim: “Yes, yes, ye. You just wait and see what tomorrow will bring. Maybe be lucky … Aye, you’ve got to realise you’ve had the stroke, you’ve got to be realistic, but I find that very difficult. Yes, when you’ve been active all your life, you can't be as active as you were. I was always on the move – then it all comes to a standstill. But you’ve got to accept that.”

Sub-themes: Understanding and accepting limitations

Interviewer: “I know there have been a lot of things you’ve had to accept you can't do … I’m wondering if you have been able to focus on other things?”

Jim: “I used to play the trumpet in a band. But I realised after the heart attack [5 years ago] I had to give it up. Aye … [Gets upset, starts to cry; Jim given the opportunity to stop but said he wanted to continue]. I cry more than I should cry … when I think about the things I used to do, and I can't do it now – that's upsetting.”

Theme: Experience of setback/ failure

Sub-themes: Understanding and accepting limitations; Emotional response

One stroke survivor (Jim) did not achieve any of his personal goals. Jim described how he had to disengage with valued goals over time due to the stroke and other health conditions. Jim was finding it difficult to consider or identify alternative goals. His account suggested he was struggling to engage in important activities, reclaim a sense of self or enhance his emotional wellbeing in the aftermath of the stroke (see Box 5).

presents on overview of these findings by illustrating how stroke survivor's personal context informs their goals; and how the experiences of success and failure during goal pursuit informs decisions about different pathways to goal attainment (or goal non-attainment).

Does the G-AP framework support different pathways to goal attainment?

Stroke survivor accounts suggested that G-AP supported different pathways to goal attainment by supporting attainment of either the original goal or an adjusted or alternative goal. Four main themes captured the reported contribution: 1. identifying personal goals, 2. motivating and sustaining goal pursuit and 3. gauging progress and making informed decisions about what to do next and 4. use of the Goal setting and Action Planning record. These themes are presented in the following sections, concluding with a contradictory account from one stroke survivor (Alexander) who did not find any aspect of the G-AP framework beneficial.

Identifying personal goals

Stroke survivors reported that agreed goals reflected their personal hopes and priorities, and that staff were collaborative in their approach. Peter (age 73) explained, “Oh yes, it's adult level [talking about goals], it's not telling, it's discussing and arriving at compromises.” When asked if goals set captured her priorities, Janet (age 72) said, “Yes, for me in my own personal situation … for me specifically.”

The “Coming up with the goals” sheet in the G-AP record (See Supplementary File 1) facilitated collaborative discussions between stroke survivors and staff about personal goals. Paul (age 56) said,

It was useful [the ‘Coming up with the goals’ sheet] because it allowed me to focus on exactly what I wanted … and it's therapeutic in a way to write it down and refer to it, and we [he and the staff] refer to it a lot.

Motivating and sustaining goal pursuit

Stroke survivors reported that their goals, action plans and coping plans motivated them to initiate and sustain goal pursuit by (i) providing impetus for change, (ii) providing focus and motivation, (iii) creating manageable steps, (iv) motivating practise and (v) overcoming barriers. Action plans written in the G-AP record acted as a “contract” and encouraged family involvement. Coping plans prompted consideration of barriers and ways to overcome them (See ).

Table 3. Motivating and sustaining goal pursuit.

Gauging progress and making informed goal decisions

Stroke survivors’ experience of (i) carrying out plans and self appraisal (ii) staff feedback, and (iii) review of their G-AP record created explicit opportunities to gauge progress and make informed goal decisions.

(i) Carrying out plans provided stroke survivors with direct experience of goal related success and setbacks. This supported realistic self appraisals which informed decisions about whether to continue goal pursuit or consider goal adjustment or disengagement. Successful action plan completion was evidence of improvement. This led to a sense of achievement, improved confidence and an enhanced sense of self and emotional wellbeing (See ). These positive outcomes motivated stroke survivors to continue pursuit of their valued goals.

Table 4. Experiences of successful action plan completion.

Failure to complete plans was evidence of unsatisfactory progress and could result in stroke survivors deciding their goal was unattainable. Although this risked a negative emotional response, stroke survivor reports suggested the experience of failure facilitated understanding and acceptance of limitations (see Box 6).

Colin (age 67): Action plan – To lift blocks with left hand (linked to goal of getting back to work as a bricklayer)

“Yes, I wanted to lift specific items with my left hand and do things with my left hand … I realise it’ll never fully happen now. I’m old enough to realise you’ve got to be disappointed in some things in life.”

Liz (age 65): Action plan – To make biscuits (linked to goal of being independent in the kitchen)

“I can't cook because … I’ve tried to, and I’ve dropped something, and I really, really badly burnt myself, so I don't. I suppose I was disappointed [about not being able to cook] – it's what I did for a living.”

Jane (age 49): Action plan – To try on high heel shoes (linked to goal of wearing high heel shoes to her son's wedding).

“When I started to walk [in the high heels] in the house I knew I wasn't going to be fine. Instead of thinking I was going to be able to walk in high, high heels, I had to decide that that was never going to happen again and what I was to do was to try the best I could with what I had.”

(ii) Staff feedback informed stroke survivors’ appraisal of their performance and progress. Positive feedback was encouraging:

She [the physiotherapist] was very pleased [when I was able to climb the hill]. She said, ‘That's really good, she said, no breathlessness, nothing’ … makes me feel brilliant!. Lorna (age 59)

I said to her [the physiotherapist] ‘Do you think I’ll ever be able to walk on my own?’ [And she said] ‘No, never without a stick, but you might be able to walk without somebody else with you. Henry (age 81)

(iii) Review of the G-AP record helped stroke survivors to gauge their progress over time and make informed adjustments to goals and plans.

I’d make a space in each week where I’d refer back to the G-AP [Goal setting and Action Planning] folder and say ‘Right, where am I? How am I doing with these goals?’ This really helps me to see it on paper and to see it broken down, d’you know what I mean? You’re actually seeing the progress and it's yours to take home. (Kim, age 28)

The methodology used in that booklet [Goal setting and Action Planning record] has been helpful for that, being able to revise things, things that we didn't achieve or we find has changed now, you know, so we’ve done that … readjust things as we go along. (Paul, age 56)

The G-AP framework was not beneficial

Alexander (age 45) had a different perspective from other stroke survivors when discussing his experience of the G-AP framework. Although he appreciated it might help others, he did not benefit from any aspect of the process. When asked if discussing goals with staff had been helpful, Alexander said,

Probably not [laugh] because they would have always have been my goals, I didn't need somebody to say – ‘What are your goals?’

I didn't really do anything. I was given exercises to do [action plans], but I didn't do them. For me I was kind of lucky … my recovery just kind of came back to me.

To me it wasn't very important, it's not as if at any point I was going to forget, ‘oh my goal is to get back to work and get my … get back my driving licence’, You know what I mean? So to me no, I mean, I could possibly see the benefit for other folk [people], but not really, it didn't really help me much.

Discussion

Achieving original, adjusted or alternative goals enabled stroke survivors to engage in activities that were important to them, reclaim a sense of self and experience emotional wellbeing. The goal setting and action planning framework supported most stroke survivors to (i) identify personal goals (ii) initiate and sustain goal pursuit (iii) gauge progress and (iv) make informed decisions about continued goal pursuit, adjustment and disengagement.

Our findings suggest that rehabilitation staff should support stroke survivors in pursuit of their valued personal goals, but anticipate that they may not achieve all of those originally set. By being ready to support goal adjustment and disengagement, staff can help stroke survivors navigate their ongoing recovery by finding different pathways to goal attainment. Other research supports the need to consider alternative pathways to goal attainment. In their qualitative study, Wood, Connelly, and Maly (Citation2010) found that the process of community reintegration in the first year after stroke was was marked by ongoing changes in stroke survivors goals and that adjusting expectations was pivotal to “getting back to real living”. In their prospective cohort study of 148 patients, Brands et al. (Citation2015) found that only 13% of initial life goals set were achieved within the first year after stroke. The authors concluded that both tenacity in goal pursuit and flexibility in goal adjustment were important to optimize adaptation after acquired brain injury.

Findings of a United Kingdom wide survey of goal setting practice with stroke survivors in community rehabilitation teams (Scobbie, Duncan, Brady, & Wyke, Citation2014) suggest that we may not be taking account of these important findings in clinical practice. The Goal Attainment Scale (Turner-Stokes, Williams, & Johnson, Citation2009) and Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Carswell et al., Citation2004) were reported as the most commonly used “formal” methods to guide goal setting practice. Both are primarily designed as outcome measures and not designed to inform practice, or measure positive outcomes, in relation to goal adjustment or disengagement. Furthermore, over a third of teams surveyed (38%) reported that they did not routinely consider downgrading or disengaging from goals proving difficult to achieve. This finding aligns with other research reporting that staff can feel ill-equipt to manage stroke survivors expectations and disappointment if anticipated progress is not being made (Sarah, Sarah, Kirk, & Parsons, Citation2016; Wiles, Ashburn, Payne, & Murphy, Citation2004). These findings suggest that current goal setting practice may not incorporate all available pathways to goal attainment and that opportunities to support recovery through adjustments to, or disengagement from goals proving difficult to achieve may be missed.

Stroke survivor accounts suggested that there were distinct end points on the spectrum of goal attainment, with those who achieved all valued goals without the need for any adjustment or disengagement at one end (Alexander), and those unable to achieve all or most of their valued goals with limited scope to re-engage with suitable alternatives at the other (Jim). Stroke survivors (like Alexander) who benefit from a full recovery within their rehabilitation episode, or who are confident in their own self-management skills, may not require the level of support and structure that G-AP has to offer. However, stroke survivors like Jim may represent a vulnerable subgroup that would benefit from early identification and additional support. There is evidence to suggest that disengagement from unattainable goals can reduce depressive symptoms in older people (Dunne, Wrosch, & Miller, Citation2011). But on a cautionary note, goal disengagement can compromise emotional wellbeing if there are no alternative goals to focus on (Wrosch, Scheier, Carver, & Schulz, Citation2003). Supporting stroke survivors who are unable to achieve their goals, and who have limited options to pursue valued alternatives, can present a difficult clinical dilemma. However, novel psychological interventions are emerging that may be worthy of consideration. For example, acceptance and commitment therapy (Majumdar & Morris, Citation2019) is a psychological intervention that focuses on promoting acceptance and pursuit of a valued life, whilst acknowledging physical limitations and psychological distress. Positive psychology based interventions (Cullen et al., Citation2018) may enhance wellbeing by increasing experiences of pleasure, engagement and meaning by focusing on character strengths such as gratitude, optimism, hope and personal growth. Whilst in need of further evaluation in full scale trials, these interventions may offer alternative ways to approach and discuss personal goals, and create more opportunities for goal related success, whilst diminishing the risk of failure.

Our findings suggest that the G-AP framework facilitated goal attainment by supporting stroke survivors to identify and pursue their personal goals. These are important contributions given the strong evidence to suggest that stroke survivors often feel that rehabilitation goals do not reflect their priorities (Rosewilliam, Roskell, & Pandyan, Citation2011; Sarah et al., Citation2016; Sugavanam, Mead, Donaghy, & van Wijke, Citation2013) and that intense, repetitive practise is required to improve outcomes, including upper limb function (Langhorne, Coupar, & Pollock, Citation2009; Pollock et al., Citation2014) and communication (Brady, Kelly, Godwin, Enderby, & Campbell, Citation2016). Perhaps the most unique contribution that the G-AP framework made was to support informed decisions about goal adjustment and disengagement through ongoing appraisal, feedback and decision making. Whilst appraisal and feedback is incorporated within other goal setting tools (Stevens, Beurskens, Köke, & van der Weijden, Citation2013), it is typically completed at the end of the intervention period in relation to rehabilitation goals identified at the outset, thus limiting opportunities for timely decisions about goal adjustment or disengagement to be made.

Limitations of this study

Our cross-sectional design captured stroke survivors’ views and experiences at one time point in their recovery journey; specific data on time since stroke was not collected. Subsequently, temporal dimensions of goal pursuit, adjustment and disengagement were not fully explored. A longitudinal design, with specific time since stroke reference points, would permit exploration of these goal options over time, including the process of finding alternative goals. This may offer important insights into when, or under what circumstances, stroke survivors should be supported to continue pursuit of their goals, rather than adjust or disengage for them. This is an important clinical question, especially in the context of stroke rehabilitation which often requires ongoing, high intensity practise over time to improve outcomes. This will be a consideration for future research.

Although our sample was broadly representative, it did not include stroke survivors with severe mobility, cognitive (for example, anosognosia) or communication deficits. Whilst these groups were not excluded from taking part, we missed a sub group of stroke survivors that may have reported different experiences of goal pursuit, adjustment and disengagement; or who would have had difficulty realistically appraising their performance to make informed goal decisions.

Finally, our qualitative findings suggest that the G-AP framework can support attainment of original, adjusted or alternative goals. However, its effectiveness in doing so needs to be demonstrated in a suitably designed evaluation of its clinical and cost effectiveness.

Conclusions

Attaining valued goals enables stroke survivors to do the activities that are important to them, reclaim a sense of self and experience emotional wellbeing. Adjusting or disengaging from goals proving too difficult to achieve creates different pathways to goal attainment. The G-AP framework facilitated attainment of original, adjusted and alternative goals by supporting stroke survivors to identify personal goals, motivate and sustain goal pursuit, gauge progress and make informed decisions about continued goal pursuit, adjustment or disengagement. Those forced to disengage from valued goals, in the absence of suitable alternatives to pursue, may require additional support.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (845.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (683.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (493.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the stoke survivors who took part in this study, sharing their experiences in the hope that it might help others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamson, J., Beswick, A., & Ebrahim, S. (2004). Is stroke the most common cause of disability? Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 13(4), 171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2004.06.003

- Banks, J. L., & Marotta, C. A. (2007). Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: Implications for stroke clinical trials: A literature review and synthesis. Stroke, 38, 1091–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(5). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub3

- Brands, I., Stapert, S., Kohler, S., Wade, D., & van Heugten, C. (2015). Life goal attainment in the adaptation process after acquired brain injury: The influence of self-efficacy and of flexibility and tenacity in goal pursuit. Clinical Rehabilitation, 29, 611–622. doi: 10.1177/0269215514549484

- Carswell, A., McColl, M. A., Baptiste, S., Law, M., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (2004). The Canadian occupational performance measure: A research and clinical literature review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 210–222. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100406

- Cullen, B., Pownall, J., Cummings, J., Baylan, S., Broomfield, N., Haig, C., … Evans, J. J. (2018). Positive PsychoTherapy in ABI Rehab (PoPsTAR): A pilot randomised controlled trial. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28, 17–33. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2015.1131722

- Dunne, E., Wrosch, C., & Miller, G. E. (2011). Goal disengagement, functional disability, and depressive symptoms in old age. Health Psychology, 30(6), 763–770. doi: 10.1037/a0024019

- Gayle, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(117). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Langhorne, P., Coupar, F., & Pollock, A. (2009). Motor recovery after stroke: A systematic review. Lancet Neurology, 8(8), 741–754. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70150-4

- Majumdar, S., & Morris, R. (2019). Brief group-based acceptance and commitment therapy for stroke survivors. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 70–90. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12198

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Paanalahti, M., Alt Murphy, M., Lundgren-Nilsson, A., & Sunnerhagen, K. S. (2014). Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for stroke by exploring the patient’s perspective on functioning in everyday life: A qualitative study. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 37(4), 302–310. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000070

- Pollock, A., Farmer, S. E., Brady, M. C., Langhorne, P., Mead, G. E., Mehrholz, J., & van Wijck, F. (2014). Interventions for improving upper limb function after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, 010820.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. G. Burgess (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). London: Routledge.

- Rosewilliam, S., Roskell, C., & Pandyan, A. (2011). A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25, 501–514. doi: 10.1177/0269215510394467

- Sarah, E. P., Sarah, F. T., Kirk, S., & Parsons, J. (2016). What are the barriers and facilitators to goal-setting during rehabilitation for stroke and other acquired brain injuries? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(9), 921–930. doi: 10.1177/0269215516655856

- Scobbie, L., Brady, M. C., Duncan, E. A., Thomson, K., & Wyke, S. (in preparation). Implementation of a Goal setting and Action Planning (G-AP) framework with stroke survivors in community rehabilitation teams: A mixed methods study.

- Scobbie, L., & Dixon, D. (2014). Theory-based approach to goal setting. In R. R. Stiegert & W. M. M. Levack (Eds.), Rehabilitation goal setting: Theory, practice and evidence (1st ed., pp. 213–235). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; Taylor & Francis Group.

- Scobbie, L., Dixon, D., & Wyke, S. (2009). Identifying and applying psychological theory to setting and achieving rehabilitation goals. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23, 321–333. doi: 10.1177/0269215509102981

- Scobbie, L., Dixon, D., & Wyke, S. (2011). Goal setting and action planning in the rehabilitation setting: Development of a theoretically informed practice framework. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25, 468–482. doi: 10.1177/0269215510389198

- Scobbie, L., Duncan, E. A., Brady, M. C., & Wyke, S. (2014). Goal setting practice in services delivering community-based stroke rehabilitation: A United Kingdom (UK) wide survey. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(14), 1291–1298. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.961652

- Scobbie, L., McLean, D., Dixon, D., Duncan, E., & Wyke, S. (2013). Implementing a framework for goal setting in community based stroke rehabilitation: A process evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 190–203. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-190

- Stevens, A., Beurskens, A., Köke, A., & van der Weijden, T. (2013). The use of patient-specific measurement instruments in the process of goal-setting: A systematic review of available instruments and their feasibility. Clinical Rehabilitation, 27(11), 1005–1019. doi: 10.1177/0269215513490178

- Sugavanam, T., Mead, G., Donaghy, M., & van Wijke, F. (2013). The effects and experiences of goal setting: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(5), 177–190. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.690501

- The Stroke Association. 2012. Struggling to recover: Life after stroke campaign briefing, p. 8. Retrieved from https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/struggling_to_recover_report_lowres.pdf

- Turner-Stokes, L., Williams, H., & Johnson, J. (2009). Goal attainment scaling: Does it provide added value as a person-centred measure for evaluation of outcome in neurorehabilitation following acquired brain injury? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41, 528–535. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0383

- Wiles, R., Ashburn, A., Payne, S., & Murphy, C. (2004). Discharge from physiotherapy following stroke: The management of disappointment. Social Science & Medicine, 59(6), 1263–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.022

- Wood, J. P., Connelly, D. M., & Maly, M. R. (2010). ‘Getting back to real living’: A qualitative study of the process of community reintegration after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24, 1045–1056. doi: 10.1177/0269215510375901

- Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Schulz, R. (2003). The importance of goal disengagement in adaptive self-regulation: When giving up is beneficial. Self & Identity, 2(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1080/15298860309021