ABSTRACT

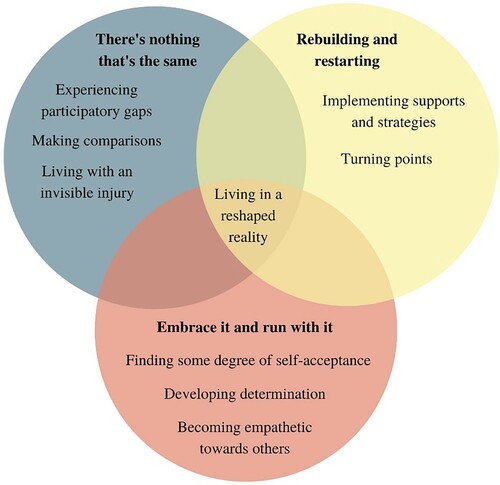

Individuals with a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) experience substantial changes in their life. This constructivist grounded theory study aimed to develop an explanatory model that explores the impact of changes in social participation and self-identity after sustaining a TBI. Sixteen participants with moderate to severe TBI (mean age = 49.8, 69% male) were recruited, and were on average 16.4 years post-injury (SD = 10.4). Data from semi-structured interviews were analysed thematically. An overarching theme of “living in a reshaped reality” was identified, which depicted how changes in social participation and self-identity influenced ongoing experiences with TBI. Three main themes were generated: (1) “there's nothing that's the same” highlighted the daily challenges individuals faced post-injury, (2) “rebuilding and restarting” described how individuals with TBI navigated through their unfamiliar reality, and (3) “embrace it and run with it” explored participants’ reactions towards life with a TBI. An explanatory model was developed, consisting of the overarching theme (“living in a reshaped reality”) with the three integrated themes. Future research and clinical practices can build on this understanding to develop programmes to help individuals address their needs in post-injury life.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects approximately 69 million individuals globally each year (Dewan et al., Citation2018). Individuals who sustain a moderate to severe TBI encounter many challenges as they resume life post-injury. These challenges may continue over the course of many years and include physical and cognitive issues, lack of resources, and problems with continued treatment and care (Downing et al., Citation2021; Fadyl et al., Citation2019; Ponsford et al., Citation2014; Ruet et al., Citation2019). These issues can impact the way people with TBI participate in activities of daily life such as work and leisure (Klepo et al., Citation2022). Additionally, it may cause changes to their self-identity or sense of self (Ownsworth, Citation2014).

People with TBI experience changes in the ways they participate in the various activities of everyday life (Jourdan et al., Citation2016; Kersey et al., Citation2019). After a TBI, individuals report reduced participation compared to their pre-injury participation levels (Goverover et al., Citation2017). This can be related to factors associated with the injury itself or environmental and social constraints. For example, individuals with TBI may have cognitive problems, which include memory and attention impairments (Beaulieu-Bonneau et al., Citation2017; Dunning et al., Citation2016; Vakil et al., Citation2019) and decreased mobility and balance, affecting their capacity to perform household tasks, or resume pre-injury activities (Perry et al., Citation2014). Additionally, they may experience a reduction in social participation due to barriers in the institutional environment (e.g., limited programmes and services) and the built environment (e.g., reduced physical access) (Fleming et al., Citation2014; Heinemann et al., Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2017). Individuals with TBI may encounter negative social attitudes such as stigma or marginalization, which decreases their community participation (Poritz et al., Citation2019). This reduction in social participation may contribute to a “gap”, where individuals experience little or no participation in their valued roles (Beadle et al., Citation2020).

Changes with self-identity are commonly reported after TBI (Beadle et al., Citation2016; Ownsworth, Citation2014). Self-identity can be defined as a continuously constructed set of characteristics that a person chooses to identify with (Ownsworth, Citation2014), which is developed through social structures and self-verification processes (Stryker & Burke, Citation2000). As such, self-identity is linked to the roles that individuals occupy (Stets & Burke, Citation2000). The impact to self-identity after TBI can be the result of biological damage (e.g., loss of autobiographical memories) and psychosocial factors (e.g., adjustment to injury) (Beadle et al., Citation2016; Yeates et al., Citation2008). Some research indicates that as individuals return to pre-injury environments or try to resume prior roles, they may be prompted to examine and compare the differences in their pre-and post-injury selves (Villa et al., Citation2021). Hence, individuals with TBI may find the attributes that formed their pre-injury selves are no longer applicable to their current selves (Levack et al., Citation2014). For example, a qualitative study showed that men with TBI were unable to identify with pre-injury characteristics they considered masculine such as being self-reliant or a provider (MacQueen et al., Citation2020). As individuals find it difficult to resume meaningful roles after the TBI, they may experience feelings of fragmentation and distress (Levack et al., Citation2014).

There has been some research on the relationship between social participation and self-identity after TBI. The inability to resume pre-injury activities can result in a disruption of self-identity (Bryson-Campbell et al., Citation2013; Conneeley, Citation2012). For example, participating in an activity can contribute to defining self-identity, however, if participation is altered due to changes in abilities and access after TBI, individuals may experience a loss of self-identity and have difficulties reconstructing a new identity (Bryson-Campbell et al., Citation2013). A meta-synthesis of TBI research on self-identity identified that if an individual with TBI occupies a new role that is attributed with a loss of status, they experience a less positive self-identity given their comparisons between their pre- and post-injury selves (Villa et al., Citation2021). However, much less is known about the subjective experiences of the changes in social participation and self-identity in the TBI population. Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop an explanatory model that illustrates the changes in social participation and self-identity after a TBI and how these changes impact an individual's life.

Methods

Study design

This study used constructivist grounded theory and aimed to follow an inductive process to create a theory grounded in the data obtained through interviews (Charmaz, Citation2006). It supports the idea that the researcher is inseparable from the data and follows an ongoing iterative process (Charmaz & Belgrave, Citation2019). Ethics approval was obtained by the Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia. Data are reported using the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Participant recruitment

Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants from British Columbia, Canada. Advertisements were circulated within GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre, BC Brain Injury Association, and other community networks. To be included in this study, participants had to: (1) be between the ages of 18–65 years, (2) experience a moderate to severe TBI, (3) sustain the injury at least a year ago, and (4) be able to communicate in English. Individuals who sustained a mild TBI were excluded from the study. Written and oral consent were obtained from all individuals prior to data collection.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed and piloted with an individual with lived experience of a brain injury (e.g., patient-partner). By piloting the interview guide with the patient-partner, the researchers modified the questions to be more suitable for the TBI population (e.g., shorter questions) and gained insight about potential interviewing techniques. Each participant took part in an approximately 40-minute interview, conducted either online through a secured virtual platform, or in-person at the participants’ place of residence, depending on the participants’ preference. Eight participants were interviewed via an online platform, while eight participants were interviewed in-person. No participants withdrew from the study and there were no prior relationships between participants and researchers. Participants were aware of the interviewer's backgrounds, as well as the goals of this research project. Participants were encouraged to talk about their life experiences after sustaining their TBI and were asked questions specific to their social participation and self-identity. Two participants requested their support workers to be present during the interviews.

The interviews were conducted by first and fourth authors RM (master's student) and JS (assistant professor), along with two research assistants (master's and undergraduate students). Four interviewers were needed in this study to conduct interviews due to time constraints faced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using four interviewers in this study could have impacted data collection, and ultimately the findings generated, as each interviewer's unique perspectives and backgrounds could have influenced the data that they co-constructed with their participants. All student interviewers received training from the lead researcher (JS) on how to conduct interviews with participants with TBI. All four interviewers were female and had previous experience interacting with people with brain injury. One interviewer was a researcher; the three other interviewers attended health or rehabilitation sciences educational programmes at the University of British Columbia, Canada. The three student interviewers were enrolled in a research graduate programme, a clinical graduate programme, and a bachelor's programme respectively. Data collection was finalized when theoretical sufficiency, a sufficient depth of understanding, was reached by the researcher to develop an explanatory model (Dey, Citation1999).

Data analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim with personal information replaced with pseudonyms. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, in line with constructivist grounded theory. Data analysis followed three main stages: (1) initial coding, (2) focused coding, and (3) theoretical coding. These stages included line-by-line coding and constantly comparing the data to generate themes. Each participant transcript was coded using the software NVivo 12. As analysis progressed, three main themes were formed, and an overarching theme was generated.

The research team employed three main trustworthiness strategies: researcher reflexivity, involvement of multiple investigators in the data analysis process, and participant verification (Morrow, Citation2005). First, each interviewer maintained a reflexive journal. After each interview, the interviewers gave their perspective on the overall content of the interview and how the participant responded to the questions. This journal was maintained to examine the influence of the interviewers’ positionality during the research process and identify any preconceived notions that may contribute to their style of questioning and anticipated responses. Some initial journal entries reflected interviewers’ assumptions that the experience of TBI consistently creates a negative life for individuals. Through journaling, interviewers were aware of these assumptions and aimed to ensure data collection and analysis remained open to all experiences after TBI, both positive and negative. Second, multiple researchers were included throughout the data analysis stages, hence acknowledging the different perspectives on the participants’ data. Following the first round of coding and generation of themes by the first author researcher RM, the other authors on this paper (WBM, JF, and JS) were invited to provide input and review the codes and themes. The themes were developed over various sessions, supporting an iterative process. Last, participant verification was conducted to include complementary perspectives from the participants about the findings. A few participants responded when contacted and after the reviewal of the findings, they indicated that it supported their perspectives about their life after TBI.

Results

Sixteen people with moderate to severe TBI participated in the study with an average time of 16.4 years post-injury (). The overarching theme of “living in a reshaped reality” depicted how an individual experienced and grappled with a different world after their TBI. Three themes were integrated in this post-injury experience: (1) “there's nothing that's the same”, identified the new challenges that individuals faced, (2) “rebuilding and restarting”, outlined how individuals navigated their new reality and acquired the necessary resources that were available to them, and (3) “embrace it and run with it”, described the responses to post-injury life. An explanatory model illustrating the findings and the relationships between social participation and self-identity was developed. Descriptions of themes with exemplar quotes are noted below after the explanatory model.

Table 1. Participant demographic (N = 16).

Explanatory model

The explanatory model () illustrates the continual nature of the process of negotiating life in a reshaped reality. William talked about his ongoing healing process, “it's like going up a hill with sand, three steps up and you slide one back”. Joshua echoed a similar notion, “I don't think there's ever an end to rehabilitation, I think it’ll be a lifelong journey”. As shown in the model, the participants’ social participation and self-identity are impacted as they live in their reshaped reality. For example, Lisa described difficulties participating in work activities, as employers could not make accommodations for her abilities and limitations. This impacted her self-identity as she was not able to occupy the role of a driver. Michael discussed the support he received from the medical staff and his family, which facilitated acceptance of his new life. He described how his newfound self-acceptance enabled him to engage in pursuits that gave back to the TBI community, such as advocacy and the creation of activities to facilitate participation for other individuals with TBI. Additionally, Andrew spoke about how he felt his TBI had a positive impact on his life and self-identity, expressing his injury as a “clean slate”. He described that after his injury he became closer to his family, started to enjoy working, and developed new milestones he wanted to achieve. Overall, as depicted in this model, participants’ experience of living in a reshaped reality is both influenced and characterized by the impacts of their TBI on social participation and self-identity. This reshaped reality is defined by a sense of change or that nothing is the same, their efforts to rebuild and restart, and embracing and running with their new reality.

Figure 1. Explanatory model of participants’ experiences of living in a reshaped reality since sustaining their TBI.

There’s nothing that’s the same

The first main theme reported the new challenges participants experienced after sustaining a TBI, with many participants indicating that adjusting to their new post-injury life was a difficult transition. Integrated in this theme are three sub-themes including (1) experiencing participatory gaps, (2) making comparisons, and (3) living with an invisible injury.

Experiencing participatory gaps

The first sub-theme described the “gaps” or obstacles encountered by participants after their injury. Participants highlighted new limitations they faced in their post-injury world, such as reduced participation in leisure and work-related activities. Jessica talked about her desire to engage in sporting activities but perceived a constant sense of uncertainty as she explored the extent of her abilities:

My battle is, every single time I play a sport that I used to be able to play and I don't know when I pick something up, am I going to be like the way I was before or am I going to be completely ‘I don't know how to play'.

Work, yeah that's where I felt, more important that I actually was. I was a somebody because of what I would actually do. I felt good when I worked. I did love my job, all my jobs. I was just so happy all the time … [Now that I’m not working] it just knocks me down … I feel inadequate, frustrated because I know what has to be done, how to work, how to set up a filing system. But I can't do it.

Making comparisons

The second sub-theme depicted two types of comparisons made by participants, the first in which they compared their pre-and post-injury identities, and the second in which they compared their abilities to those of people without a TBI. In terms of comparing pre- and post-injury selves, David expressed his thoughts on his pre-injury independence and how he struggled with not being self-reliant anymore – a characteristic that he associated with his masculine identity:

It's mainly because when you’re independent, and self-employed, and self-reliant, and energetic. And everything. And then after? … I suffered really, really, really bad. Because I lost a lot of pride. And that's really hard on a man. Pride is everything.

Participants compared their capabilities to those without a TBI. For example, Michael said:

I read all the time, I’ll try to better myself, and that's where I feel a little bit insignificant at times, because my wife is a very, very intelligent woman … we don't deal with work … I mean, we’re a great team but a little bit I feel behind, I’m not as smart as she is.

Living with an invisible injury

The third sub-theme outlined participants’ experiences when other individuals portrayed a lack of understanding about their TBI. Lisa talked about the criticism she received due to her behavioural changes, “Don't be so rough. When I just think well, if they only knew, like they’re just judging. They mean well, but there are some times when they’re doing more harm, because they forget I’m not like them”. Jessica expressed her discomfort when she encountered individuals who expected her to be the same person she was pre-injury:

Lots of people who knew me from before, they have expectations of who I’m supposed to be, right? Who they think I am … so when those people reach out, my first thing is to brace myself, there is always a, not expectation, but there is always a preconceived notion of who I am, and all of those things are fighting with you.

Rebuilding and restarting

The second main theme highlighted the resources and measures taken by the participants to help them navigate life after TBI. Two sub-themes are incorporated in this theme. These consist of (1) implementing supports and strategies and (2) turning points.

Implementing supports and strategies

The need for support, from both healthcare and social groups, was highlighted in this first sub-theme, with participants emphasising support as an essential resource to navigate daily life. Andrew stated that even though he did not want to participate in his rehabilitation, his clinician's constant encouragement was essential in improving his capabilities:

I remember thinking, it's selfish for all of you to want me to keep going because this sucks. But it truly is awesome now … When you don't get results it's hard to want to keep trying new things. I had this lovely lady, the one that kept pushing me to do stuff and challenging me, and then I know that now, when I’m climbing on something, I think, oh good thing she pushed me actually.

At one point, I finally said, I think I need to see someone. I think I need some help, like a counsellor or something like that. And my dad's response was, oh, no, you’re fine. So just the denial that there's anything wrong. And I mean, they don't deny that it happened, but it's like they just want to kind of move on … Well, it just pushed me further into depression … . because it's like, well, now I want help, but I can't get it.

In addition to the healthcare and social support needed, participants described the practices or strategies they cultivated that allowed them to engage in their post-injury life the way they desired. For example, Jessica reported:

And for me the strategy right now in the morning is to mentally prepare myself, not to have sudden things, surprises are not fun for me. Cause I want to mentally prepare, cognitively prepare. It's also one of my strategies, especially if I’m in a group surrounding.

Turning points

The second sub-theme described participants’ accounts of experiencing a turning point where participants found a purpose in life, which led them to embrace and improve their situation. Robert reported how he shifted his priorities and found meaning in raising his children, after realising that he will not be able to resume his vocational role:

I had to keep telling myself that it's okay that you’re not working, you still are, you’re raising children here. That's a big job in itself. So that was the biggest push. If I couldn't have that, then I was going to raise my kids the best that I can. Without this strong motivation, I wouldn't be sitting here talking to you and we wouldn't be having all this right now.

Embrace it and run with it

The third main theme outlined the different ways in which participants responded to their new reality of living with a TBI. Sub-themes included (1) finding some degree of self-acceptance, (2) developing determination, and (3) becoming empathetic towards others.

Finding some degree of self-acceptance

The first sub-theme reported the varying degrees of acceptance that participants showed towards their TBI. Many participants acknowledged the change in their abilities and expressed compassion towards their post-injury selves. John said, “Just take everything as it comes. Take it slowly. Let yourself get used to it. Don't try and be like your old person. No, you just know you’re never going back. Just accept it, it’ll be okay”. Michael conveyed time as an important factor when living with a TBI:

Time is the most important thing in the world because you got to be patient, because it's not going to happen tomorrow … For me too, it's been 23 years, I’ll never ever be the same that I was. Acceptance and time are the two most important things in the world.

I cried the first time I couldn't read. I couldn't pick a book up again. The first time I picked the book up was four years after … That is probably my biggest thing, the first time we tried was so devastating. And it took me months before we tried to read again. But it's like to pick up a book and to do it by myself. It's so scary.

Developing determination

The second sub-theme illustrated participants’ accounts of the determination and resilience they developed to overcome the daily issues that materialized post-injury. These participants conveyed positive personal traits and attitudes they adopted in the face of challenges, such as Michael, “I remember looking out of the balcony and saying, what's gonna happen, I’ve lost everything. So, I said to myself, you know what to do, it's time to go, it's time to put my socks and get back into things.” Joshua gave another example, emphasising his self-efficacy to face the challenges ahead:

The doctors, the nurses, the therapist, they were saying, this isn't gonna happen, this is going to be this way. And I know the stubbornness or whatever, I just smiled and said, ‘sure thank you I appreciate that', and then just not going to let that happen to me. Having that mindset is a big part of how I am today, the recovery I’ve been through.

Becoming empathetic towards others

The third sub-theme depicted participants’ reflections on their empathy for others who had gone through similar experiences. Joshua expressed how he wanted to help others the way he was supported:

I think that I was in a bad place, but I had people around me, I had people to help me. For me knowing that those people were there, changed my life, and changed the trajectory of my life … So, I think I’m in a position where I want to be able to help and I can say I was in your shoes, I was where you were a couple years ago, three years ago. I’m doing much better because of the people who were there.

Discussion

This study identified an overarching theme of “living in a reshaped reality” and three underpinning themes that depicted life after TBI: “there's nothing that's the same”, “rebuilding and restarting”, and “embrace it and run with it”. This study builds on previous research to develop an explanatory model and explore participant perspectives on the changes experienced in their social participation and self-identity after a TBI. Participants in our study had a mean age of 49.8 years and were on average 16.4 years post-injury. While our study did not specifically investigate the impact of the participants’ age or the duration since their injury on social participation and identity, previous research has shown that these factors can influence an individual's social participation and self-identity (Ownsworth, Citation2014; Vos et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it may be possible that given the older age and longer post-injury duration of most of the participants in our study, they were able to reflect, develop a new course, or achieve their turning point. The following discussion considers these themes with a focus on social participation and self-identity.

Social participation

The first theme, “there's nothing that's the same”, described the difficulties encountered by participants when engaging in meaningful activities (e.g., resuming employment or leisure activities) due to changes in their abilities as well as social and environmental constraints. Individuals who experience greater injury severity and more cognitive impairments after TBI are less likely to be employed (Chien et al., Citation2017; Ponsford & Spitz, Citation2015). This could be a result of the lack of vocational rehabilitation, limited support from employers and colleagues, and decreased abilities and function (Matérne et al., Citation2017). Participants in our study have also identified the problems faced when they tried to engage in sports or exercise. Previous research has indicated that individuals with TBI may experience a change to more sedentary leisure activities post-injury, citing reasons such as fatigue, lack of transportation, and financial constraints (Wise et al., Citation2010). This shift can negatively impact an individual, as research findings have reported that individuals involved in physical activities after a TBI have portrayed an increase in mood and quality of life (Hoffman et al., Citation2010; Wise et al., Citation2012). As such, individuals may be largely impacted when they find themselves unable to engage in their desired activities.

Participants whose experiences were illustrated in the second theme, “rebuilding and restarting”, described personal strategies and social support as essential resources to help them participate in activities and navigate their post-injury life. This aligns with earlier work indicating that clinicians aid individuals with TBI to create patient-led solutions for facilitating engagement in meaningful activities (Knox et al., Citation2013). Receiving services during early rehabilitation is important as it influences long-term level of functioning and participation (Lefkovits et al., Citation2021). Participants in our study described the benefits of long-term supports such as brain injury communities and peer support. Participating in activities after TBI can be an ongoing process, and as such, long-term support services are essential in helping individuals through the new and unexpected problems that can arise (Fadyl et al., Citation2019). However, individuals in this study and others have acknowledged that it can be harder to access long-term medical support (Strandberg, Citation2009). This may reflect unawareness of resources available as well as the continuous struggle to obtain help from services (Fadyl et al., Citation2019; Stiekema et al., Citation2020). Notably, previous qualitative investigations identified that most individuals indicate that social support also deteriorates after sustaining a brain injury (Fraas & Calvert, Citation2009; Lefkovits et al., Citation2021). There is a clear need for better healthcare and social support to facilitate participation in activities after TBI, particularly regarding the education and support for the caregivers of those with TBI (Lieshout et al., Citation2020; Powell et al., Citation2017).

Findings from the third theme, “embrace it and run with it” highlighted participants’ feelings of empathy and desire to help others with disabilities. Many participants acted on this outlook by engaging in roles that developed their new interest in helping others. This contrasts with some other studies indicating that people with TBI experience decreased empathy, due to damage in brain structures associated with cognitive and emotional empathy (de Sousa et al., Citation2010; Wearne et al., Citation2020). However, these quantitative studies did not explore participant experiences with TBI. Participants in our study described how they reflected on their own challenges in life and were able to recognize the needs and vulnerability in others with disabilities, aligning to other studies on empathy after injury (Powell et al., Citation2007). Additionally, this reflected the volunteer nature of the participants in this study as these individuals wanted to share their experiences and help further research on TBI.

Self-identity

Findings from the first theme “there's nothing that's the same”, described the impacts to self-identity after TBI, which includes changes in the different roles they occupy (e.g., professional, leisure, familial). A systematic review indicated that individuals are more commonly reported to experience negative changes to their self-identity after TBI (Beadle et al., Citation2016). While there were both positive and negative self-identity changes stated by the participants in this study, one of the main negative self-identity changes highlighted by the men in our study were the perceived losses in masculine identity. This is consistent with other research studies in which after a TBI, men described the changes they experienced as conflicting with their pre-injury masculine ideals (e.g., switching roles from being the breadwinner to domestic roles) (MacQueen et al., Citation2020). This can be due to the influence of cultural and societal ideals where men are framed as the primary earners of a family. These influences can also impact women, as women with TBI may find it difficult to adjust to their change in roles from caregiver to receiving care and continue to engage in caregiving despite the possibility of health risks (Fabricius et al., Citation2020). However, individuals with TBI may accept these changes by reformulating their ideals of the characteristics that form their masculine identity and finding positive meanings in new roles (e.g., perceiving domestic roles as a way to support the family) (Jones & Curtin, Citation2011).

The first theme depicted participants’ accounts of TBI as an “invisible injury” as identified by individuals in other studies (Lefkovits et al., Citation2021; Lorenz, Citation2010). This description of their TBI as “invisible” describes an injury that is not obviously observable (e.g., memory impairment) compared to physical impairments (e.g., balance difficulty requiring the use of a cane). In other studies, individuals with TBI expressed that they preferred the invisible nature of their injury as it aligned with their desire to be perceived as “normal” and able-bodied (Freeman et al., Citation2015). However, participants in our study expressed feelings of being misunderstood by others in their community and social circle because of incorrect assumptions about their physical well-being and behaviour. If an individual does not display external indicators of an injury, others may not understand that an individual has a disability and hence minimize the challenges the individual experiences (Lowe et al., Citation2021; McClure, Citation2011).

Participants highlighted how they navigated through the challenges of life after TBI by striving to create a positive self-identity. Participants talked about experiencing a “turning point” in their life after TBI that caused a questioning and redefining of their values and goals. This aligns with a qualitative study, which reported a considerable shift in self as they recognized there were new opportunities that lay ahead post-injury, enabling them to take a positive next step (Muenchberger et al., Citation2008). In the second theme, participants described experiences that provided a direction or purpose in life by engaging in meaningful activities, as well as achieving milestones or successes. This is consistent with the findings of a scoping review that stated the experience of having a positive perspective on life and achieving accomplishments can have further impetus of positive life experiences and promote resiliency after TBI (Nalder et al., Citation2022).

Resiliency was indicated by individuals whose accounts were reflected in the third theme, “embrace it and run with it”, which depicted how they responded to life after their injury. Participants described characteristics such as hope and self-efficacy (the belief in their own capabilities) that helped protect them from the prolonged negativity after TBI. Perceived self-efficacy is associated with life satisfaction as it enables the individual to try and attain their desired outcomes (Cicerone & Azulay, Citation2007). Characteristics of hope and self-efficacy are theorized to facilitate resiliency after TBI, which in turn can promote acceptance of self and abilities (Nalder et al., Citation2019). Given that resiliency includes positive adaptations, the personal attributes of hope and self-efficacy may have helped participants to foster resiliency, which in turn led them to accept their new self after TBI. The TBI resiliency model (Nalder et al., Citation2019) also places importance on external resources, social support, and family resiliency to promote an individual's resiliency.

The third theme reported the varying degrees of acceptance participants experienced towards their TBI. A few participants reported feelings of grief and denial. Grieving can be an important process of acceptance after TBI (Hooson et al., Citation2013). After a TBI, an individual may grieve for the loss of an anticipated future that an individual expected to experience, as well as the realization that some aspects of life might never be the same as pre-injury, and represent a loss of future self (Ownsworth, Citation2014; Ruff, Citation2013). A few participants described instances where they previously avoided aspects of their injury or did not want to acknowledge the limitations and difficulties resulting from their TBI. This can be perceived as a self-protective mechanism and be indicative of impaired self-awareness. The biopsychosocial model of self-awareness explores this approach, where at the psychological level, individuals may use strategies such as avoidant coping or denial (Ownsworth et al., Citation2006). An exploratory study suggested that when individuals with TBI realized that their abilities had changed, denial helped them to cope better in the short term (O’callaghan et al., Citation2006). Hence, denial can be viewed as a protective mechanism for the individual, acting as a “buffer” to the emotional distress felt when confronted with their post-injury change (Gainotti, Citation1993). However, the continuous use of these strategies overtime can impact an individual negatively as they may fail to implement other essential coping strategies (Ownsworth, Citation2005).

Acceptance of self after TBI can be influenced by many factors, such as time since injury. The length of time living with a TBI can be important as described in the sub-theme of “finding some degree of self-acceptance”, as individuals may need opportunities over the course of time to obtain feedback from participating in different activities and thus readjust their expectations to life (Ellingsen & Aas, Citation2009). Additionally, a longitudinal study indicated that as time progressed, individuals adopted a more positive perspective on life and accepted their injury as they encountered more positive experiences (Lefkovits et al., Citation2021). However, in this case, individuals may be recalibrating their representation of a negative encounter, for example perceiving it as more positive due to the comparisons with newly encountered adverse events (Schwartz et al., Citation2007). Individuals may experience a re-prioritization whereby they change what they consider positive, or re-conceptualization where they re-define the meaning of a positive experience (Schwartz et al., Citation2007). Most participants in this current study sustained the TBI many years previous and as such may have had more opportunities to accept their re-shaped reality of life. Acceptance of TBI may also be influenced by the awareness of their impairments and understanding the extent of their capabilities (Fadyl et al., Citation2019). In acknowledging their limitations, it helps facilitate engagement in therapy, as well as contribute to positive growth (Allen et al., Citation2022; O’Callaghan et al., Citation2012). Notably, acceptance of injury is a key factor in reconstructing positive self-identity (Levack et al., Citation2014).

Clinical implications

There were three main clinical implications from our study. First, through the theme “there's nothing that's the same”, clinicians can gain insight on individuals’ altered social participation after TBI and the consequent positive impact of discovering new activities to engage in post-injury. Therefore, people with TBI may benefit from the identification of meaningful activities they wish to pursue post-injury. Second, findings from the first theme highlighted the potential benefit of educating family members about life roles and activity changes after TBI, as the impact of a TBI may be misunderstood or minimized due to its invisible nature. By delivering client-centred psychoeducation, family and friends may create a more supportive environment for the clients’ rehabilitation. Third, findings from the theme “rebuilding and restarting” emphasize the importance of support to navigate life after TBI. In this way, health services may consider ways to ensure both short- and long-term healthcare support are available for people with TBI.

Limitations

This study has three main limitations. First, data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, hence when asked about their social participation after TBI, participants added COVID-19 related problems as well. However, the interviewers clarified the question by asking the participants to answer according to their pre-COVID-19 participation. Second, some participants who had more severe impairments may not have been able to engage fully in the interview due to fatigue and cognitive processing difficulties. These participants were purposively recruited to provide a wide level of abilities and experiences in life after TBI and were supported in the interview with support workers. Third, theoretical sampling, a process central to constructivist grounded theory, was not implemented due to recruitment difficulties and time constraints. Therefore, deeper insights into categories may not have been generated in this study.

Conclusion

This study describes the experience of living with a TBI, illustrating the new reality an individual experiences after a TBI. Findings indicate that individuals with TBI encounter new challenges, respond to these challenges with supports and strategies, and react in various ways to their post-injury life. Future research and clinical practice may benefit from exploring how individuals can develop and strengthen their responses to the adverse encounters after TBI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants who took part in this study as well as the BC Brain Injury Association for assistance in recruitment. The authors would also like to thank research assistants Anika Cheng and Rebecca Tsow for their help in the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, N., Hevey, D., Carton, S., & O’Keeffe, F. (2022). Life is about “constant evolution”: The experience of living with an acquired brain injury in individuals who report higher or lower posttraumatic growth. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(14), 3479–3492. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1867654

- Beadle, E. J., Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., & Shum, D. (2016). The impact of traumatic brain injury on self-identity: A systematic review of the evidence for self-concept changes. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 31(2), E12–E25. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000158

- Beadle, E. J., Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., & Shum, D. (2020). The nature of occupational gaps and relationship with mood, psychosocial functioning and self-discrepancy after severe traumatic brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(10), 1414–1422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1527954

- Beaulieu-Bonneau, S., Fortier-Brochu, É, Ivers, H., & Morin, C. M. (2017). Attention following traumatic brain injury: Neuropsychological and driving simulator data, and association with sleep, sleepiness, and fatigue. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(2), 216–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1077145

- Bryson-Campbell, M., Shaw, L., O’Brien, J., Holmes, J., & Magalhaes, L. (2013). A scoping review on occupational and self identity after a brain injury. Work, 44(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-01561

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Charmaz, K., & Belgrave, L. L. (2019). Thinking about data with grounded theory. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(8), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418809455

- Chien, D. K., Hwang, H. F., & Lin, M. R. (2017). Injury severity measures for predicting return-to-work after a traumatic brain injury. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 98, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.09.025

- Cicerone, K. D., & Azulay, J. (2007). Perceived self-efficacy and life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(5), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000290970.56130.81

- Conneeley, A. L. (2012). Transitions and brain injury: A qualitative study exploring the journey of people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 13(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2012.3

- de Sousa, A., McDonald, S., Rushby, J., Li, S., Dimoska, A., & James, C. (2010). Why don’t you feel how I feel? Insight into the absence of empathy after severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychologia, 48(12), 3585–3595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.08.008

- Dewan, M. C., Rattani, A., Gupta, S., Baticulon, R. E., Hung, Y. C., Punchak, M., Agrawal, A., Adeleye, A. O., Shrime, M. G., Rubiano, A. M., Rosenfeld, J. V., & Park, K. B. (2018). Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1080–1097. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352

- Dey, I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for grounded theory inquiry. Academic Press.

- Downing, M., Hicks, A., Braaf, S., Myles, D., Gabbe, B., Cameron, P., Ameratunga, S., & Ponsford, J. (2021). Factors facilitating recovery following severe traumatic brain injury: A qualitative study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(6), 889–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1744453

- Dunning, D. L., Westgate, B., & Adlam, A. R. (2016). A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in survivors of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology, 30(7), 811–819. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000285

- Ellingsen, K. L., & Aas, R. W. (2009). Work participation after acquired brain injury: Experiences of inhibiting and facilitating factors. International Journal of Disability Management, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1375/jdmr.4.1.1

- Fabricius, A. M., D’Souza, A., Amodio, V., Colantonio, A., & Mollayeva, T. (2020). Women’s gendered experiences of traumatic brain injury. Qualitative Health Research, 30(7), 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319900163

- Fadyl, J. K., Theadom, A., Channon, A., & McPherson, K. M. (2019). Recovery and adaptation after traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: Longitudinal qualitative findings over the first two years. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(7), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1364653

- Fleming, J., Nalder, E., Alves-Stein, S., & Cornwell, P. (2014). The effect of environmental barriers on community integration for individuals with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 29(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e318286545d

- Fraas, M. R., & Calvert, M. (2009). The use of narratives to identify characteristics leading to a productive life following acquired brain injury. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(4), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2009/08-0008)

- Freeman, A., Adams, M., & Ashworth, F. (2015). An exploration of the experience of self in the social world for men following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 25(2), 189–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.917686

- Gainotti, G. (1993). Emotional and psychosocial problems after brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 3(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602019308401440

- Goverover, Y., Genova, H., Smith, A., Chiaravalloti, N., & Lengenfelder, J. (2017). Changes in activity participation following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(4), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1168746

- Heinemann, A. W., Magasi, S., Hammel, J., Carlozzi, N. E., Garcia, S. F., Hahn, E. A., Lai, J. S., Tulsky, D., Gray, D. B., Hollingsworth, H., & Jerousek, S. (2015). Environmental factors item development for persons with stroke, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(4), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.024

- Hoffman, J. M., Bell, K. R., Powell, J. M., Behr, J., Dunn, E. C., Dikmen, S., & Bombardier, C. H. (2010). A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve mood after traumatic brain injury. PM & R, 2(10), 911–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.06.008

- Hooson, J. M., Coetzer, R., Stew, G., & Moore, A. (2013). Patients’ experience of return to work rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: A phenomenological study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 23(1), 19–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2012.713314

- Jones, J. A., & Curtin, M. (2011). Reformulating masculinity: Traumatic brain injury and the gendered nature of care and domestic roles. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(17-18), 1568–1578. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.537803

- Jourdan, C., Bayen, E., Pradat-Diehl, P., Ghout, I., Darnoux, E., Azerad, S., Vallat-Azouvi, C., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Ruet, A., & Azouvi, P. (2016). A comprehensive picture of 4-year outcome of severe brain injuries. Results from the Paris-TBI study. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 59(2), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2015.10.009

- Kersey, J., Terhorst, L., Wu, C., & Skidmore, E. (2019). A scoping review of predictors of community integration following traumatic brain injury: A search for meaningful associations. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 34(4), E32–E41. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000442

- Klepo, I., Sangster Jokić, C., & Tršinski, D. (2022). The role of occupational participation for people with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of the literature. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(13), 2988–3001. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1858351

- Knox, L., Douglas, J. M., & Bigby, C. (2013). Whose decision is it anyway? How clinicians support decision-making participation after acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(22), 1926–1932. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.766270

- Lefkovits, A. M., Hicks, A. J., Downing, M., & Ponsford, J. (2021). Surviving the “silent epidemic”: A qualitative exploration of the long-term journey after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(10), 1582–1606. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1787849

- Levack, W. M., Boland, P., Taylor, W. J., Siegert, R. J., Kayes, N. M., Fadyl, J. K., & McPherson, K. M. (2014). Establishing a person-centred framework of self-identity after traumatic brain injury: A grounded theory study to inform measure development. BMJ Open, 4(5), e004630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004630

- Lieshout, K., Oates, J., Baker, A., Unsworth, C. A., Cameron, I. D., Schmidt, J., & Lannin, N. A. (2020). Burden and preparedness amongst informal caregivers of adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6386. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176386

- Lorenz, L. S. (2010). Visual metaphors of living with brain injury: Exploring and communicating lived experience with an invisible injury. Visual Studies, 25(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.523273

- Lowe, N., Crawley, L., Wilson, C., & Waldron, B. (2021). ‘Lonely in my head’: The experiences of loneliness in individuals with brain injury. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12481

- MacQueen, R., Fisher, P., & Williams, D. (2020). A qualitative investigation of masculine identity after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(2), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1466714

- Matérne, M., Lundqvist, L. O., & Strandberg, T. (2017). Opportunities and barriers for successful return to work after acquired brain injury: A patient perspective. Work, 56(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162468

- McClure, J. (2011). The role of causal attributions in public misconceptions about brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 56(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023354

- Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

- Muenchberger, H., Kendall, E., & Neal, R. (2008). Identity transition following traumatic brain injury: A dynamic process of contraction, expansion and tentative balance. Brain Injury, 22(12), 979–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050802530532

- Nalder, E., Hartman, L., Hunt, A., & King, G. (2019). Traumatic brain injury resiliency model: A conceptual model to guide rehabilitation research and practice. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(22), 2708–2717. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1474495

- Nalder, E., King, G., Hunt, A. W., Hartman, L. R., Szigeti, Z., Drake, E., Shah, R., Sharzad, M., Resnick, M., Pereira, G., & Lenton, E. (2022). Indicators of life success from the perspective of individuals with traumatic brain injury: A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–14. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.2025274

- O’Callaghan, A., McAllister, L., & Wilson, L. (2012). Insight vs readiness: Factors affecting engagement in therapy from the perspectives of adults with TBI and their significant others. Brain Injury, 26(13-14), 1599–1610. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2012.698788

- O’callaghan, C., Powell, T., & Oyebode, J. (2006). An exploration of the experience of gaining awareness of deficit in people who have suffered a traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 16(5), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500368834

- Ownsworth, T. (2005). The impact of defensive denial upon adjustment following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychoanalysis, 7(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2005.10773476

- Ownsworth, T. (2014). Self-Identity after brain injury. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315819549

- Ownsworth, T., Clare, L., & Morris, R. (2006). An integrated biopsychosocial approach to understanding awareness deficits in Alzheimer’s disease and brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 16(4), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500505641

- Perry, S. B., Woollard, J., Little, S., & Shroyer, K. (2014). Relationships among measures of balance, gait, and community integration in people with brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 29(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182864f2f

- Ponsford, J. L., Downing, M. G., Olver, J., Ponsford, M., Acher, R., Carty, M., & Spitz, G. (2014). Longitudinal follow-up of patients with traumatic brain injury: Outcome at two, five, and ten years post-injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 31(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2013.2997

- Ponsford, J. L., & Spitz, G. (2015). Stability of employment over the first 3 years following traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30(3), E1–E11. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000033

- Poritz, J. M. P., Harik, L. M., Vos, L., Ngan, E., Leon-Novelo, L., & Sherer, M. (2019). Perceived stigma and its association with participation following traumatic brain injury. Stigma and Health, 4(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000122

- Powell, J. M., Wise, E. K., Brockway, J. A., Fraser, R., Temkin, N., & Bell, K. R. (2017). Characteristics and concerns of caregivers of adults with traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 32(1), E33–E41. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000219

- Powell, T., Ekin-Wood, A., & Collin, C. (2007). Post-traumatic growth after head injury: A long-term follow-up. Brain Injury, 21(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050601106245

- Ruet, A., Bayen, E., Jourdan, C., Ghout, I., Meaude, L., Lalanne, A., Pradat-Diehl, P., Nelson, G., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Vallat-Azouvi, C., & Azouvi, P. (2019). A detailed overview of long-term outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury eight years post-injury. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00120

- Ruff, R. (2013). Selecting the appropriate psychotherapies for individuals with traumatic brain injury: What works and what does not? NeuroRehabilitation, 32(4), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-130901

- Schwartz, C. E., Andresen, E. M., Nosek, M. A., Krahn, G. L. & RRTC Expert Panel on Health Status Measurement. (2007). Response shift theory: Important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(4), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.032

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

- Stiekema, A., Winkens, I., Ponds, R., De Vugt, M. E., & Van Heugten, C. M. (2020). Finding a new balance in life: A qualitative study on perceived long-term needs of people with acquired brain injury and partners. Brain Injury, 34(3), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1725125

- Strandberg, T. (2009). Adults with acquired traumatic brain injury: Experiences of a changeover process and consequences in everyday life. Social Work in Health Care, 48(3), 276–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380802599240

- Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695840

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Vakil, E., Greenstein, Y., Weiss, I., & Shtein, S. (2019). The effects of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury on episodic memory: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 29(3), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-019-09413-8

- Villa, D., Causer, H., & Riley, G. A. (2021). Experiences that challenge self-identity following traumatic brain injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(23), 3298–3314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1743773

- Vos, L., Poritz, J., Ngan, E., Leon-Novelo, L., & Sherer, M. (2019). The relationship between resilience, emotional distress, and community participation outcomes following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 33(13-14), 1615–1623. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1658132

- Wearne, T. A., Osborne-Crowley, K., Logan, J. A., Wilson, E., Rushby, J., & McDonald, S. (2020). Understanding how others feel: Evaluating the relationship between empathy and various aspects of emotion recognition following severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology, 34(3), 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000609

- Wise, E. K., Hoffman, J. M., Powell, J. M., Bombardier, C. H., & Bell, K. R. (2012). Benefits of exercise maintenance after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(8), 1319–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.05.009

- Wise, E. K., Mathews-Dalton, C., Dikmen, S., Temkin, N., Machamer, J., Bell, K., & Powell, J. M. (2010). Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(9), 1357–1362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.009

- Wong, A., Ng, S., Dashner, J., Baum, M. C., Hammel, J., Magasi, S., Lai, J. S., Carlozzi, N. E., Tulsky, D. S., Miskovic, A., Goldsmith, A., & Heinemann, A. W. (2017). Relationships between environmental factors and participation in adults with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury: A cross-sectional multi-center study. Quality of Life Research, 26(10), 2633–2645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1586-5

- Yeates, G. N., Gracey, F., & McGrath, J. C. (2008). A biopsychosocial deconstruction of “personality change” following acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(5-6), 566–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010802151532

Appendix. Interview Guide

General questions

1. Tell me about your brain injury.

2. What has your journey of rehabilitation been like?

Prompt: Are you currently receiving rehabilitation?

Social participation questions

1. What does a typical day for you look like?

Prompt: Can you talk through what you do?

2. How if at all has your daily activities changed since your injury?

Prompt: What do you do now, what did you do before the injury? How has your injury changed your daily activities?

Self-Identity questions

1. How would you describe yourself?

Prompt: Who are you, what are you like, what makes you “you”? Any examples of how you think about yourself, your personality. What roles are important to you?

2. How if at all has your brain injury changed the way you think about yourself?

Prompt: What have you learnt about yourself? What have you discovered about yourself since your injury?

3. What do you think is important for students, clinicians, and the community to know about the experience of having a brain injury?