ABSTRACT

During the early recovery period after traumatic brain injury (TBI), referred to as post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), approximately 44% of individuals may exhibit agitated behaviours. Agitation can impede recovery and poses a significant management challenge for healthcare services. As families provide significant support for their injured relatives during this time, this study aimed to explore the family’s experience during PTA to better understand their role in agitation management. There were 20 qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted with 24 family members of patients exhibiting agitation during early TBI recovery (75% female, aged 30–71 years), predominantly parents (n = 12), spouses (n = 7) and children (n = 3). The interviews explored the family’s experience of supporting their relative exhibiting agitation during PTA. The interviews were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis, which revealed three key themes: family contributions to patient care, expectations of the health care service and supporting families to support patients. This study emphasized the significant role of families in managing agitation during early TBI recovery and highlighted that families who are well-informed and well-supported have the potential to minimize their relative’s agitation during PTA, which may reduce the burden on healthcare staff and promote patient recovery.

Introduction

Individuals who sustain a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) will typically experience an acute period of disorientation and amnesia, known as post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) (Russell & Smith, Citation1961; Schwartz et al., Citation1998; Tate et al., Citation2000). Approximately 44% of patients in PTA will exhibit agitated behaviours (Phyland et al., Citation2021), including restlessness, perseveration, frustration intolerance, impulsivity, resistance to care and aggression (Amato et al., Citation2012; Bogner et al., Citation2001; Lequerica et al., Citation2007; McNett et al., Citation2012; Nott et al., Citation2006; Sandel & Mysiw, Citation1996; Weir et al., Citation2006). These behaviours can pose a significant challenge to recovery. Patients who exhibit agitated behaviours may refuse care and disengage with therapy, leading to poorer rehabilitation outcomes, such as reduced independence and longer hospital stay (Bogner et al., Citation2001; Kadyan et al., Citation2004; Lequerica et al., Citation2007; McNett et al., Citation2012; Nott et al., Citation2006; Singh et al., Citation2014; Spiteri et al., Citation2021). Agitated behaviours also pose a risk of harm to family members, healthcare staff and other patients, and such behaviours often demand considerable resources which increases the burden on families, clinicians and the healthcare system (Becker, Citation2012; Brooke et al., Citation1992; Montgomery et al., Citation1997; Sandel & Mysiw, Citation1996). The effective management of agitation following TBI represents an ongoing challenge for healthcare services worldwide, and our understanding of best practice for agitation management is limited (Carrier et al., Citation2022; Fugate et al., Citation1997; McNett et al., Citation2012).

Families are often highly involved in TBI care and can be a source of substantial support for patients who are agitated, both during the early recovery phase (Lefebvre et al., Citation2005; Oyesanya, Citation2017; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2005) and following transition to community living (Degeneffe, Citation2001; Jumisko et al., Citation2007; Lefebvre et al., Citation2008; Testa et al., Citation2006). Behavioural changes after TBI can have a significant long-term impact on families (Degeneffe, Citation2001; Jumisko et al., Citation2007; Lefebvre et al., Citation2008), contributing to relationship strain, mental health issues, reduced family functioning and increased stress (Anderson et al., Citation2002; Braine, Citation2011; Brooks et al., Citation1987; Ergh et al., Citation2003; Lefebvre et al., Citation2008; Riley, Citation2007; Schönberger et al., Citation2010; Tam et al., Citation2015). Families are often the main source of support for individuals with TBI during their hospital stay, spending time by the bedside and offering physical, emotional, practical and financial support (Lefebvre et al., Citation2005; Oyesanya, Citation2017; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2005). A growing body of research highlights the experiences of families providing care for relatives with a TBI during their hospital stay (Choustikova et al., Citation2020; Fleming et al., Citation2012; Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010; Lefebvre et al., Citation2005; Leith et al., Citation2004; Othman et al., Citation2021; Oyesanya et al., Citation2021; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017b; Rotondi et al., Citation2007; Stenberg et al., Citation2020; Turner et al., Citation2007). Key themes identified include the family’s need for information, education and support from staff, the benefits of family involvement for emotional and physical support, decision-making and managing visitors; the importance of seeing progress to help maintain hope; and the need for a family-centered, multidisciplinary approach to TBI care (Choustikova et al., Citation2020; Ergh et al., Citation2002; Fleming et al., Citation2012; Gagnon et al., Citation2016; Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010; Lefebvre et al., Citation2005; Leith et al., Citation2004; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017b; Rotondi et al., Citation2007; Stenberg et al., Citation2020).

Recent qualitative research with clinicians highlighted the importance of involving families in patient care and educating families about recovery during PTA for the effective management of agitation (Carrier & McKay, Citation2022). However, there has been limited research on the experience of families specifically during this PTA period, and in particular, the impact of agitated behaviours on families, and how families cope with these behaviours during early recovery. Given families represent a significant support system during the hospitalized period, it is important to understand their experience and the challenges associated with managing agitation, to maximize support for families during this time and optimize care for their loved ones.

The present study aimed to explore the experiences of family members who were providing support for patients who were hospitalized, agitated and in PTA following moderate-severe TBI.

Methods

Participants

Participants were family members and the key contact of patients who were admitted to a level 1 TBI rehabilitation unit that provides specialized subacute inpatient rehabilitation services. Patients were either current inpatients or discharged within the last twelve months and exhibited agitation during early TBI recovery. Inclusion criteria for family members included: aged 18 years or older, proficient in English (to understand the interview questions and consent process), self-identified as the key family caregiver who visited the patient in-person at the acute and/or rehabilitation hospitals and had witnessed agitated behaviours during the patient’s hospital stay. There were no criteria regarding the frequency or duration of visitation as visitor regulations varied as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inclusion criteria for the patient included: aged 16 years or older, sustained a moderate or severe TBI (defined as a PTA duration > 24 h), a current inpatient during study administration or discharged within the last twelve months and demonstrated clinically significant agitation (defined as scores > 22 on the Agitated Behaviour Scale [Corrigan, Citation1989] or clinical notes describing agitation).

Eligible participants were identified by a member of the clinical care team, who provided the family member with information about the study, including a study flyer, explanatory statement, and contact details of the lead researcher, who was not involved in the provision of healthcare services to these patients. Participants who expressed an interest in the research were asked to contact the research team via the contact details provided on the study flyer (via phone, email or QR code). The lead researcher then contacted the participant to guide them through the formal consent process, which included providing time for the participants to ask questions. Participants were emailed the participant information and consent form to review and once completed, the researcher contacted participants to arrange a time to complete the interview. This stepped process offered participants multiple opportunities to consider their involvement in the study.

There were 28 eligible families of patients on the inpatient rehabilitation unit during the study administration period (2021–2022). Of the 28 family members contacted (via phone or in-person), two declined, five could not be reached after several contact attempts, and one was known to the lead researcher, resulting in 20 completed interviews. Several participants expressed a desire for an additional family member to accompany them and contribute to the interview. There were four participants who completed an interview as a pair. In determining sample size, there were several factors to consider in relation to information power, including study aim, sample specificity, use of established theory, quality of dialogue and analysis strategy (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a; Malterud et al., Citation2016). Whilst the nature of the aim was broad and there was somewhat limited theoretical background (relating specifically to agitated behaviours), there were numerous characteristics of this study that lent to a smaller sample, such as the denser specificity of the experiences and knowledge of the participants, the stronger dialogue as a result of clear communication between researcher and participant and the researcher’s prior experience working with a similar population, and the use of a cross-case analysis to explore the study aim. On balance, the authors considered the current sample size to be sufficient for meeting the demands of information power.

Study design and procedure

This study used a qualitative descriptive design involving semi-structured interviews to explore the experiences of family members of patients exhibiting agitation during PTA. This study was approved by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided informed consent. This research was reported according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; see Supplementary Material for checklist) (Tong et al., Citation2007). Whilst acknowledged as a suitable checklist for qualitative research, it should be noted that several criteria of the COREQ are not consistent with the method of reflexive thematic analysis, such as the use of a codebook and the notion of data saturation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a).

The interviews were conducted between July 2021 and June 2022 with the interview questions targeting the research aims which were derived from the key literature in this field (see Supplementary Material for detailed interview schedule). In particular, the interviews focused on understanding the key challenges for families during this period, the information families received, their perception of effective agitation management strategies and how clinicians can better support families and patients during this early stage of TBI recovery. Interview questions were open-ended, and prompts were used to elicit detailed responses. The interview schedule was piloted initially with one of the co-authors and then the first participant involved in this study to confirm the questions were clear and appropriate (Newman & Ridenour, Citation1998). Interviews were conducted via teleconferencing platform (n = 16) or phone (n = 4) with only participants and interviewer present and had a mean duration of 63 min. The interviews were conducted by author SC (female), who is a clinical neuropsychology PhD candidate with training in qualitative research methods and clinical experience working with people with TBI and their families. The interviewer was not known to any of the participants. Participants were aware that the interviewer was completing this research as part of their PhD. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Brief field notes were made following each interview. The deidentified transcripts were analyzed via an ongoing comparative method of data collection and analysis.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to interpret the data and facilitate the identification and analysis of themes and patterns (Braun et al., Citation2012), with an emphasis on the researcher’s role in the interpretation of meaningful patterns across a dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Byrne, Citation2022). A constructionist epistemology was adopted, whereby the meaningfulness of the data was a central consideration, whilst acknowledging the importance of recurrence in the data (Burr, Citation1995; Byrne, Citation2022; Schwandt, Citation1994). An inductive (i.e., data-driven) approach was used as data were open-coded to better capture the meaning communicated by participants, rather than coding the data to a pre-existing framework (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). Some deductive analysis was applied to ensure the themes were relevant to the research questions.

The interviews were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s six phase process: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) generating themes, (4) reviewing potential themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report (Braun et al., Citation2012; Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b). This process was iterative and recursive, and the research team moved through these phases in a non-linear fashion (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a). The interview recordings were first reviewed alongside the transcripts to become familiar with the data, as well as other relevant factors that cannot be captured in the transcript texts alone (such as tone). The transcripts were then carefully read and re-read and the data were assigned initial codes using qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12, QSR International). Both semantic and latent meaning was coded (i.e., what was expressed by the participant and the researcher’s interpretation of the data respectively). Themes were generated based on the relationship between the codes. A preliminary thematic map was developed to collate the codes and themes (Braun et al., Citation2012). The themes were then collaboratively reviewed by the research team to sense-check ideas, develop richer interpretations of the data and improve overall study rigour (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). The themes were named and defined based on analysis of the data rather than in relation to the interview questions.

Author SC conducted the thematic analysis in consultation with JP and AM. An important component of research involving reflexive analysis is to acknowledge the researcher’s position and background and consider the potential influence this could have on the study’s findings (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b). The lead researcher SC, who conducted all the interviews, was a PhD candidate who had several years of research and clinical experience working closely with patients with TBI and their families at the time the study was conducted. SC had recently completed qualitative interviews with clinicians working with patients with TBI, and so had developed a sound understanding of the field of interest and interviewing skills. The consultation with senior researchers AM and JP was an important safeguard to ensure no relevant areas were being overlooked. Participants were aware that the author was a PhD candidate and that the author was not associated with the delivery of their healthcare service. The field notes captured after each interview also provided an opportunity for reflexive practice.

Results

Participant demographics

There were 20 interviews conducted with 24 family members (16 individual interviews and four paired interviews). Participants included 18 females and 6 males with a mean age of 52.38 years (SD = 12.90, range = 30–71). Over half of participants (58.33%) lived regionally and participants had an average of 13 years’ education. Relationships with the patient included parent (n = 12), spouse (n = 7), child (n = 3), parent-in-law (n = 1) and cousin (n = 1). Twenty-one family members had known the patient more than 15 years, and 15 participants lived with the patient at the time of injury. Frequency of family visitation varied considerably, ranging from once a month to everyday in both acute and inpatient settings, with a mean visitation frequency of 4.80 times per week in the acute setting and 4.04 times per week in the inpatient setting. The situation in Victoria Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic was such that hospital visitor restrictions frequently changed throughout the pandemic and consequently throughout this study period. Participants were subject to a range of different restrictions that fluctuated across time and across hospitals. Their relatives with TBI included 16 males and 4 females, with an average age at injury of 42.50 years (SD = 20.29, range = 16–86). Average PTA duration was 64.10 days (SD = 53.25, range = 13–189 days) and average time since injury was 296.50 days (SD = 177.80, range = 54–775 days); see for participant demographics and for patient demographics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of interviewed participants.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients.

Key themes

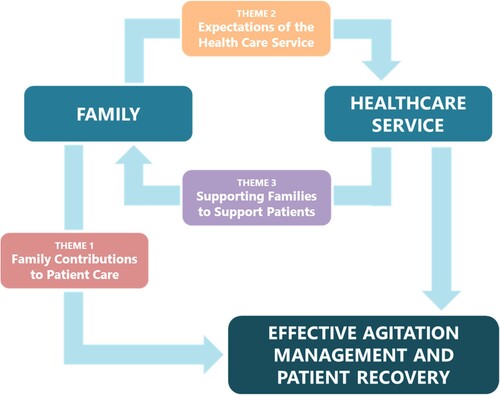

The themes identified from the interviews reflected factors considered important for improving patient recovery including: (1) family contributions to patient care; (2) expectations of the health care service; (3) supporting families to support patients. These themes are described in and presented in , which highlights the relationship between the healthcare service and the family in managing agitation and patient recovery during PTA.

Figure 1. A visual representation of the thematic analysis.

Table 3. Results of thematic analysis.

Theme 1: family contributions to patient care

Comforter and companion

Families commonly reflected on their role of comforting and providing company for the patient during early TBI recovery and the positive impact this had on agitation levels. This often involved spending time with the patient, listening to their concerns, providing reassurance that they were safe and cared for, and soothing physical contact to calm the patient. Families were frequently able to “settle” (P14) the patient during their visit, often leaving them “sound asleep” (P14). They also brought in familiar belongings and photographs and reminisced on past memories, which were considered comforting for the patient. Physical touch was important for managing patients with agitation, and for most families this helped them feel connected to the patient and helped reduce restlessness, with one participant making the comparison: “That physical touch of a family member is probably 100 times better than a Panadol” (P13). Families also felt that regular visitation was important for keeping the patient occupied by providing “extra stimulation of people from his life prior” (P3), as well as offering a distraction from the patient’s injury. Consequently, many families were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 hospital visitor restrictions on their loved one’s recovery and worried about social isolation and time apart from their family:

I think definitely 12 weeks of having no family, no visitors, nothing, would have put him back. I think if he had more stimulation, if he had more of a reminder of his normal family and friends coming in to see him, I think … he could have gotten out of PTA a bit quicker. (P23)

Custodian and communicator

Families described one of their greatest strengths as being their knowledge of the patient they could share with others. Knowing what the patient was like before the injury provided important context for clinicians and could help inform how staff and families managed agitation. For example, one parent stated:

I think as a parent, you know what your kid’s like, what you can and can’t do, but staff only know him as a patient. So I think we had a better understanding of what we can say to him and what we probably shouldn’t say at that time. (P10)

Theme 2: expectations of the health care service

Compassionate and consistent care

It was important to families that clinicians were able to deliver compassionate and consistent care to the patient. Families described the most helpful clinicians as those who were kind, respectful and demonstrated genuine care for the patient:

There were some really good nurses there and obviously that makes a huge difference when you feel like they connected with James*, because you just go, “Okay, great. Someone is looking after him.” (P20)

Consistency in care delivery was a key factor that families considered effective for managing agitation and which increased their confidence in the patient’s quality of care. Consistency across hospitals, disciplines and clinicians was important for improving families’ experience and developing trust in the healthcare system. One participant expressed frustration about inconsistencies in staff advice: “They got us to read a whole list of rules that they had, which makes complete sense to us but then they seemed to not follow those rules” (P16).

Creating a therapeutic environment

Many families described challenges to agitation management in the acute wards which were “way too busy” (P20), including loud noises, bright lights, mixed patient populations and limited staffing. Family members reflected positively on the transition to the rehabilitation unit, which better addressed the specialized needs of a patient with TBI. However, family members also expressed concern when they felt their family member was under-stimulated or lacking social interaction. Some families found the dark room and use of the Craig bed (i.e., enclosed bed with padded walls) “really difficult” (P20). Frequently, families found the use of a Craig bed to be more confronting than the use of physical restraints, as they had an easier time understanding the need for restraints. One participant recalled:

The hard part for me was seeing him … in a dark space with very little stimulation. He was in a small hospital room with like blue padded walls around him, the window was blocked off, the light was never on. He was just lying in the dark when I did go in to see him and telling me how he wanted to get out of that room. It was hard for me knowing he was in that room. (P21)

Theme 3: supporting families to support patients

“Keep Us in the loop”: including families in care

Many families stressed the importance of regular and comprehensive updates on the patient’s condition and being involved in treatment discussions. Typically, family members were looking for functional updates, such as “how he’s responding to things, basically if he’s improving, what they need to work on” (P24). Most family members preferred honest updates that reflected both the positive and challenging aspects of the patient’s recovery. Positive feedback helped families “see little improvements each day” (P14) and such feedback promoted feelings of hope and gratefulness, which were some positive ways families coped with the injury. Family members were also interested in updates about the patient’s agitation, particularly if they were planning on visiting, and families appreciated clear direction from staff about whether it was appropriate to visit. One family member said:

I would always speak to somebody prior [to visiting]. On a number of occasions when Michele* was really, really agitated and aggressive then I would make a phone call before I left just to check in, or the nursing staff on a number of occasions said to me, “we don’t think it’s a great day for you to visit.” (P8)

“Is this forever?” normalizing the recovery process

Families also emphasized the need for information about expectations for short-term and long-term patient recovery. One of the most challenging aspects of the early TBI recovery for families was witnessing the patient experiencing disorientation, amnesia and reduced cognitive capacity typical of the PTA period. Families found it deeply upsetting to see their loved one in such an incapacitated and vulnerable state and such behaviours often left families wondering whether the patient was going to “be like this forever” (P1, P9). This was evident across most interviews, even when family members had a medical background or previous medical experience. It was clear that families were looking for validation and reassurance that the patient’s experience was a “normal” part of the recovery process:

As you’re getting to the two-week mark and there’s no improvement … It was like, well, is this ever gonna end? … Is he ever gonna get better … And not having anyone there to … say to you, “No, this can be quite normal depending on the severity of his accident.” Yeah, to be told it’s quite normal, “cause it is quite confronting that, all of a sudden, there’s this person that is really unrecognisable”. (P7)

“I’m exhausted”: caring for the families

Families described feeling “overwhelmed” (P4) and “exhaust[ed]” (P11, P13) during early TBI recovery. Families were not only managing the grief and trauma associated with a traumatic injury, but they were also battling exhaustion, fear and guilt: “It was exhausting. I was very tired, emotionally” (P24). This sentiment highlighted the challenges associated with prolonged PTA duration and complex medical recoveries. The patient’s lack of cognitive capacity meant that family members were often juggling logistical issues, such as decision-making, whilst also managing their grief. One participant recalled: “I was maybe getting an hour sleep ‘cause I’d go to bed, I’d lie there for three hours, just running through my head what I’ve got to do the next day” (P19).

Many families described the need to “look after ourselves” (P16) during early TBI recovery. Families highlighted the value of debriefing after a challenging visit to reduce the likelihood of “crying in the car all the way home” (P19). One family member recommended “a set little area where you can go and bawl your eyes … and decompress … or you can meet with either a social worker or a neuropsych [sic] or one of the nursing staff there, just have a bit of a debrief” (P8). Other recommended resources included an information pack about who families could contact for support, as quite often they had information for the patient, but lacked resources for themselves. Several family members wished they had “take[n] a break” (P11) from visiting the patient to care for themselves, and for some, the hospital restrictions offered forced respite:

Restricted visitation in a way helped me, that we weren’t allowed to just hang around the whole day … I don’t think hanging around the hospital all the time and being a martyr to them is going to help. You really have to be in a good form yourself to pass on that positive vibe because … they did react to negative vibes. (P23)

In terms of challenging behaviours, families described repetitive behaviours and perseveration around leaving hospital to be particularly exhausting and upsetting to manage. When asked about the most challenging behaviours, one family member explained:

I can tell you, that’s easy, repetitive questions – “When are you taking me home?” Totally. That could have a sharp edge in it. I wouldn’t have called it anger but he’d say, “Why won’t you take me home? I wanna go home. There’s nothing wrong with me.” I would get that every time … that was probably the thing I hated the most. (P18)

Family members also acknowledged their reliance on external supports, such as family and friends, to help them through difficult times. Several family members wanted to talk to other families with similar experiences, such as via a peer support group. The family member’s relationship with the patient also influenced their coping capacity, with spouses typically finding this recovery period more challenging. It was clear that families who were able to care for themselves felt they had greater capacity to care for the patient.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the experiences of family members managing a patient exhibiting agitation during early TBI recovery, with the overarching aim of better understanding how to support family members and patients during this challenging time. The results revealed that families tackled a range of complex emotional experiences and changes throughout the early TBI recovery period, such as distress and trauma relating to the injury and medical interventions, fear and concern about both acute and long-term patient outcomes, exhaustion and a sense of being overwhelmed in relation to ongoing care and management of the patient, and guilt and frustration for circumstances where family members could not alleviate their loved one’s distress. Previous research suggests this can also be complicated by loss of an anticipated future, changes in self-identity and a sense of distance from the person with the TBI, who may not recall the early trauma experienced by the family members (Whiffin et al., Citation2019). These experiences highlight the importance of attending to the narrative changes experienced by families that can leave them feeling “disoriented and disconnected from themselves” [61,p.128]. Despite these challenges, it was evident across all of the interviews conducted that families felt their involvement was paramount for patient recovery. Families described a number of ways in which healthcare services could better support families and patients during early TBI recovery, including involving families in patient care, normalizing the post-TBI recovery process and offering support services specifically for families.

How families support patients

Families felt that their involvement during early TBI recovery was beneficial for patient recovery and managing agitation (Fleming et al., Citation2012). Consistent with past research (Pegg et al., Citation2005; Lefebvre et al., Citation2005; Rotondi et al., Citation2007), it was clear that families felt they could provide significant physical, emotional and practical support for patients, particularly in their ability to provide comfort and care for their loved one in a time of distress. The regular presence of family members may provide a sense of familiarity and stability in an overwhelming hospital environment and family visitation can offer a welcome distraction for patients, which may reduce agitation levels. Distraction is a strategy used for managing agitation (Carrier et al., Citation2022; Fluharty & Glassman, Citation2001; Fluharty & Wallat, Citation1997), and it was felt that the presence of the family member alone (i.e., in the absence of any deliberate strategies) may distract from agitating stimuli. Families in the current study also considered that their presence represented a link between the patient and the events of the outside world, which is consistent with previous research (Fleming et al., Citation2012), and which may assist disoriented patients in contextualizing their surroundings.

Families typically have an intuitive sense of the strategies that can be used to manage agitation due to their intimate knowledge of the patient. Many families felt this was an important contribution in the context of PTA, as it could help staff better understand the patient and their needs (Nalder et al., Citation2012), enabling them to tailor behaviour management strategies to patients’ personalities and premorbid interests. The family’s prior knowledge of the patient also helped identify subtle improvements throughout the recovery process and their understanding and description of the patient's mannerisms and character traits, such as their use of humour, helped families retain a sense of connection with the injured person and conjured a sense of hope for the future (Whiffin et al., Citation2019; Whiffin & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022). This benefit has been noted in other ABI research (Gebhardt et al., Citation2011) and highlights the importance of consulting with families during early recovery.

The comfort and safety provided by family members allows them to draw upon physical strategies to reduce agitation, such as stroking the patient’s head or holding their hand. This is reflected in research in acute health conditions where families described supporting their loved one with physical touch and comfort (Chapman et al., Citation2016). In a study of patients with moderate to severe TBI, families described the value of physical and verbal reassurance for managing the patient’s emotions (Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a). This sense of comfort, love and care that families can offer may help patients feel safe and secure and thus reduce agitation. Families also reflected on the usefulness of familiarizing information for reducing agitation, such as personal belongings or photographs, which is consistent with recommendations and previous research (Carrier et al., Citation2021; Oyesanya & Bowers, Citation2017a; Ponsford et al., Citation2014).

How healthcare services can support families

It is immensely important for families to feel that they can trust the healthcare service to provide appropriate care and that the patients are “in good hands” (Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010). This reduces the care burden on families, as they can focus their visit on spending time with the patient rather than tending to care needs or seeking staff to do so. This is consistent with recent research highlighting the importance of a humanizing framework to create a sense of safety, trust and human connection between clinicians and families (Holloway & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022). The types of clinicians families considered more effective for agitation management were those who were flexible, compassionate and consistent in their interactions, which was in line with previous research on effective agitation management (Carrier & McKay, Citation2022) and research highlighting the importance of adapting the environment to respond to the families’ and patient’s needs (Holloway & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022). This suggests that agitation management involves more than just effective interventions; it is also essential to have experienced and educated clinicians implementing these interventions. Compassionate clinicians also set a valuable example for other staff members, as well as families and visitors in terms of how to interact with patients who are agitated. This research supported the notion that positive interactions with staff can help families develop a sense of trust in the healthcare services (Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010).

Families felt more at ease once their loved one was transferred to the TBI rehabilitation unit, as the care was specialized for TBI patients and families were able to see the positive impact of the environment on the patient’s agitation. The rehabilitation ward was more pleasant for visiting families, who could spend time alone with the patient in their single-bed room or in outdoor communal areas. However, there were some aspects of the rehabilitation environment that families found challenging, particularly the use of more restrictive practices such as the Craig bed, as families found it difficult emotionally to witness their loved one being confined, even when compared to medication or restraint use. This is consistent with findings by Fleming et al. (Citation2012), whereby families felt uncomfortable with their loved one being “confined” (p. 187). This suggests it is important that families understand the purpose of the interventions and what the alternatives are, that families are well-informed before they encounter the use of such strategies and that use of outdoor and communal areas are maximized where possible.

In line with previous findings (Bond et al., Citation2003; Brereton & Nolan, Citation2002; Fleming et al., Citation2012; Garrett & Cowdell, Citation2005; Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010; Mirr, Citation1991), families wanted to be included in discussions around patient care, including receiving regular updates on the patient’s condition and detailed information about the injury and prognosis. They preferred more information rather than less, as being informed helped families gain a sense of control. The “perceived need for information” is a frequent theme that arises in ABI family research (Bond et al., Citation2003; Brereton & Nolan, Citation2002; Fleming et al., Citation2012; Garrett & Cowdell, Citation2005; Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010; Mirr, Citation1991). Families typically seek honest information and tangible examples of progress (Leibach et al., Citation2014; Norup et al., Citation2015), as this reinforces families’ sense of hope and helps them remain positive (Gebhardt et al., Citation2011). The impairments associated with PTA, including disorientation and amnesia, and the transitory nature of PTA were difficult for families to witness and understand, which in part may be due to the “invisible” nature of the injury, compounded by the patient’s own lack of insight. These findings highlight the importance of collaboration between clinicians and families (Carlsson et al., Citation2016; Frampton et al., Citation2017), including staff normalizing the behaviours that are typical for this period of recovery and validating the family’s experience in dealing with these behaviours (Whiffin & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022).

In the current study, many families felt they were not receiving sufficient information from clinicians. This may reflect the impact of COVID-19 visitor restrictions which meant family members relied on updates from staff. However, previous research suggests this is a common sentiment among families (Choustikova et al., Citation2020) and there continues to be a discrepancy between what clinicians and families perceive to be sufficient information (Coco et al., Citation2012). It is important that healthcare services review the information provided to families, considering the format (i.e., verbal and written) and the delivery (i.e., timing and consistency). Findings from the current study and previous research (Marcus, Citation2014) suggest that providing written information alongside verbal information may help families better understand the content. Families also prefer to receive the information from one source (Bond et al., Citation2003) and having clinicians available at the time of visitation may ensure families have access to appropriate support during challenging times. Services should consider creating a safe space for families to receive important information and debrief after their visit, as research suggests that communicating information in a calm environment and allowing sufficient time for processing can help families feel better supported (Fleming et al., Citation2009; Leibach et al., Citation2014).

The impact of a traumatic injury on families was reported to be immense and involved ongoing and evolving challenges that left families feeling overwhelmed, fearful, exhausted and guilty, consistent with previous research (Bond et al., Citation2003; Fraser, Citation1999; Lutz et al., Citation2011; Mirr, Citation1991; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2005). Families clearly required additional support, as they were focused on the care of the patient (Silva-Smith, Citation2007), and often compromized on meeting their own needs. This research has highlighted the additional challenges posed by the presence of agitated behaviours during early TBI recovery. For example, families were often met with frequent, repetitive and persistent demands to be taken home, which could easily escalate to verbal aggression, leading to guilt and frustration for families attempting to care for these patients. Based on these interviews, families were more significantly impacted by behaviours that triggered feelings of guilt or helplessness, and which challenged their capacity to care for the patient. These families appeared less concerned with behaviours that interfered with care or therapy, although they could appreciate how these behaviours impacted overall recovery.

Families also need to be consulted early in the recovery process regarding their own support needs, as this can inform healthcare services as to how to best support the family (Kneafsey & Gawthorpe, Citation2004). Clinicians may support families by offering information about family support services available and encouraging families to take a break and care for themselves, which may help reduce their sense of guilt and ease exhaustion. Families who received greater social and emotional support from family and friends found it easier to cope and thus family members with limited social support may require increased input from the healthcare team (Keenan & Joseph, Citation2010). Establishing a peer support group may be an important area for future development (Choustikova et al., Citation2020), as several families expressed a desire to communicate with families with lived experience, which may help develop a sense of togetherness and agency (Holloway & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022). It is also important to consider the family member’s relationship with the patient and their level of dependence on the patient, as this may dictate their support needs (e.g., a spouse caring for a child may need more practical support than the parent of an adult patient). This research emphasized the importance of creating a space for family members needs to be adequately addressed, which can help families members make sense of their experience and reconstruct their identities in a meaningful way (Whiffin et al., Citation2019; Whiffin & Ellis-Hill, Citation2022).

Limitations

The study sample likely reflected the experience of engaged family members and may not reflect the experiences of families who were less involved in patient care. Furthermore, the sample only reflects the experiences of families at one specialized TBI unit and two acute care hospitals. The rehabilitation ward provides a highly specialized service that is designed to manage patients in early TBI recovery. The ward also predominantly admits patients funded through a no-fault compensation scheme, and thus these patients may not be representative of the TBI population more broadly. Future research should consider multiple healthcare sites, including those with mixed patient rehabilitation populations, to get a better sense of the breadth of challenges faced by family members. Some interviews were conducted several months post-injury, which may have affected participants’ recall of events, although due to the severity of their injury, many patients had only recently emerged from PTA. Some interviews with family members were conducted in pairs (typically the parents of the patient). This provides the opportunity to observe interactions between pairs of participants which can add depth to the information collected and may help participants feel comfortable and supported throughout the interview process. However, there is also potential for power dynamics within the pair to impact the nature of the information collected and the overall study findings (Wilson et al., Citation2016). This is an important consideration for future work in this area. The COVID-19 pandemic also had an impact on the families involved in this study, which has been noted in similar research (Othman et al., Citation2021) and the meaningfulness of some themes (such as the benefits of the family and the need for information) may be overstated due to the impact of visitor restrictions.

Concluding remarks

Families are often highly involved in patient care during early TBI recovery yet there is limited research on their experience managing a loved one who is agitated during this period. These qualitative family interviews highlighted the benefits of family involvement in the effective management of agitation. The interviews also highlighted the importance of addressing the support needs of families as a core aspect of patient care. It was clear that a well-informed and well-supported family member was key to effective agitation management. There are many initiatives that services can implement to better support families during early TBI recovery which may reduce family burden as well as helping to manage patient agitation and promote recovery.

Supplementary_Material_2_Interview_Schedule.docx

Download MS Word (16.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the families for their time and willingness to share their deeply personal and challenging experiences with us. This research would not be possible without you. We would also like to acknowledge Anna Salcman for her assistance with participant recruitment. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amato, S., Resan, M., & Mion, L. (2012). The feasibility, reliability, and clinical utility of the Agitated Behavior Scale in brain-injured rehabilitation patients. Rehabilitation Nursing, 37(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/RNJ.00001

- Anderson, M. I., Parmenter, T. R., & Mok, M. (2002). The relationship between neurobehavioural problems of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), family functioning and the psychological well-being of the spouse/caregiver: Path model analysis. Brain Injury, 16(9), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050210128906

- Becker, C. (2012). Nursing care of the brain injury patient on a locked neurobehavioral unit. Rehabilitation Nursing, 37(4), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.50

- Bogner, J., Corrigan, J. D., Fugate, L., Mysiw, W. J., & Clinchot, D. (2001). Role of agitation in prediction of outcomes after traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(9), 636–644. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200109000-00002

- Bond, A. E., Draeger, C. R. L., Mandleco, B., & Donnelly, M. (2003). Needs of family members of patients With severe traumatic brain injury. Critical Care Nurse, 23(4), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2003.23.4.63

- Braine, M. E. (2011). The experience of living with a family member with challenging behavior post acquired brain injury. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 43(3), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182135bb2

- Braun, V, & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic & D. L. Long (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021a). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021b). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13, 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Brereton, L., & Nolan, M. (2002). “Seeking”: A key activity for new family carers of stroke survivors. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 11(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00564.x

- Brooke, M. M., Questad, K. A., Patterson, D. R., & Bashak, K. J. (1992). Agitation and restlessness after closed head injury: A prospective study of 100 consecutive admissions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73(4), 320–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(92)90003-F

- Brooks, N., Campsie, L., Symington, C., Beattie, A., & McKinlay, W. (1987). The effects of severe head injury on patient and relative within seven years of injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 2(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-198709000-00003

- Burr, V. (1995). An introduction to social constructionism. Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of braun and clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Carlsson, E., Carlsson, A. A., Prenkert, M., & Svantesson, M. (2016). Ways of understanding being a healthcare professional in the role of family member of a patient admitted to hospital. A phenomenographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 53, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.004

- Carrier, S. L., Hicks, A. J., Ponsford, J., & McKay, A. (2021). Managing agitation during early recovery in adults with traumatic brain injury: An international survey. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64(5), 101532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101532

- Carrier, S. L., & McKay, P. J. (2022). A. Managing agitation during early recovery following traumatic brain injury: Qualitative interviews with clinicians. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2135771.

- Carrier, S. L., Ponsford, J., Phyland, R. K., Hicks, A. J., & McKay, A. (2022). Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for agitation during post-traumatic amnesia following traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Neuropsychology Review, 33, 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-022-09544-5

- Chapman, D. K., Collingridge, D. S., Mitchell, L. A., Wright, E. S., Hopkins, R. O., Butler, J. M., & Brown, S. M. (2016). Satisfaction With elimination of all visitation restrictions in a mixed-profile intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 25(1), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2016789

- Choustikova, J., Turunen, H., Tuominen-Salo, H., Tuominen-Salo, H., & Coco, K. (2020). Traumatic brain injury patients’ family members’ evaluations of the social support provided by healthcare professionals in acute care hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(17-18), 3325–3335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15359

- Coco, K., Tossavainen, K., Jääskeläinen, J. E., & Hannele, T. (2012). Finnish nurses’ views of support provided to families about traumatic brain injury patients’ daily activities and care. Journal of Nursing Education, 3, 112–123. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v3n3p112

- Corrigan, J. D. (1989). Development of a scale for assessment of agitation following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 11(2), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/01688638908400888

- Degeneffe, C. E. (2001). Family caregiving and traumatic brain injury. Health & Social Work, 26(4), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/26.4.257

- Ergh, T. C., Hanks, R. A., Rapport, L. J., & Coleman, R. D. (2003). Social support moderates caregiver life satisfaction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25(8), 1090–1101. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.25.8.1090.16735

- Ergh, T. C., Rapport, L. J., Coleman, R. D., & Hanks, R. A. (2002). Predictors of caregiver and family functioning following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17(2), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200204000-00006

- Fleming, J., Kuipers, P., Foster, M., Smith, S., & Doig, E. (2009). Evaluation of an outpatient, peer group intervention for people with acquired brain injury based on the ICF “environment” dimension. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(20), 1666–1675. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280902738425

- Fleming, J., Sampson, J., Cornwell, P., Turner, B., & Griffin, J. (2012). Brain injury rehabilitation: The lived experience of inpatients and their family caregivers. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.611531

- Fluharty, G., & Glassman, N. (2001). Use of antecedent control to improve the outcome of rehabilitation for a client with frontal lobe injury and intolerance for auditory and tactile stimuli. Brain Injury, 15(11), 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050010025795

- Fluharty, G., & Wallat, C. (1997). Modifying the environment to optimize outcome for people with behavior disorders associated with anosognosia. NeuroRehabilitation, 9(3), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-1997-9307

- Frampton, S. B., Planetree, Guastello, S., Hoy, L., Naylor, M., Sheridan, S., & Johnston-Fleece, M. (2017). Harnessing evidence and experience to change culture: A guiding framework for patient and family engaged care. NAM perspect [cited 2022 Aug 8]; 7. Available from: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Harnessing-Evidence-and-Experience-to-Change-Culture-A-Guiding-Framework-for-Patient-and-Family-Engaged-Care.pdf

- Fraser, C. (1999). The experience of transition for a daughter caregiver of a stroke survivor. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 31(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-199902000-00002

- Fugate, L. P., Spacek, L. A., Kresty, L. A., Levy, C. E., Johnson, J. C., & Mysiw, W. J. (1997). Measurement and treatment of agitation following traumatic brain injury: II. A survey of the brain injury special interest group of the American academy of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78(9), 924–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90051-4

- Gagnon, A., Lin, J., & Stergiou-Kita, M. (2016). Family members facilitating community re-integration and return to productivity following traumatic brain injury - motivations, roles and challenges. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(5), 433–441. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1044035

- Garrett, D., & Cowdell, F. (2005). Information needs of patients and carers following stroke. Nursing Older People, 17(6), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2005.09.17.6.14.c2386

- Gebhardt, M. C., McGehee, L. A., Grindel, C. G., & Testani-Dufour, L. (2011). Caregiver and nurse hopes for recovery of patients with acquired brain injury. Rehabilitation Nursing, 36(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2011.tb00059.x

- Holloway, M., & Ellis-Hill, C. (2022). Humanising health and social care: What do family members of people with a severe acquired brain injury value most in service provision. Brain Impairment, 23(1), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2021.36

- Jumisko, E., Lexell, J., & Söderberg, S. (2007). Living with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury: The meaning of family members’ experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(3), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840707303842

- Kadyan, V., Mysiw, W. J., Bogner, J., Corrigan, J. D., Fugate, L. P., Clinchot, D. M., Corrigan, J. D., Fugate, L. P., & Clinchot, D. M. (2004). Gender differences in agitation after traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 83(10), 747–752. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHM.0000140790.30468.F4

- Keenan, A., & Joseph, L. (2010). The needs of family members of severe traumatic brain injured patients during critical and acute care: A qualitative study. Canadian Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 32, 25–35.

- Kneafsey, R., & Gawthorpe, D. (2004). Head injury: Long-term consequences for patients and families and implications for nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(5), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00903.x

- Lefebvre, H., Cloutier, G., & Josée Levert, M. (2008). Perspectives of survivors of traumatic brain injury and their caregivers on long-term social integration. Brain Injury, 22(7-8), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050802158243

- Lefebvre, H., Pelchat, D., Swaine, B., Gélinas, I., & Levert, M. J. (2005). The experiences of individuals with a traumatic brain injury, families, physicians and health professionals regarding care provided throughout the continuum. Brain Injury, 19(8), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050400025026

- Leibach, G. G., Trapp, S. K., Perrin, P. B., Everhart, R. S., Cabrera, T. V., Jimenez-Maldonado, M., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2014). Family needs and TBI caregiver mental health in Guadalajara, Mexico. NeuroRehabilitation, 34(1), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-131013

- Leith, K. H., Phillips, L., & Sample, P. L. (2004). Exploring the service needs and experiences of persons with TBI and their families: The South Carolina experience. Brain Injury, 18(12), 1191–1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050410001719943

- Lequerica, A. H., Rapport, L. J., Loeher, K., Axelrod, B. N., Vangel, S. J., & Hanks, R. A. (2007). Agitation in acquired brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(3), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000271118.96780.bc

- Lutz, B. J., Young, M. E., Cox, K. J., Ellen Young, M., Martz, C., & Rae Creasy, K. (2011). The crisis of stroke: Experiences of patients and their family caregivers. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 18(6), 786–797. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1806-786

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Marcus, C. (2014). Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: A review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.900450

- McNett, M., Sarver, W., & Wilczewski, P. (2012). The prevalence, treatment and outcomes of agitation among patients with brain injury admitted to acute care units. Brain Injury, 26(9), 1155–1162. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2012.667587

- Mirr, M. P. (1991). Factors affecting decisions made by family members of patients with severe head injury. Heart & Lung, 20, 228–235.

- Montgomery, P., Kitten, M., & Niemiec, C. (1997). The agitated patient with brain injury and the rehabilitation staff: Bridging the gap of misunderstanding. Rehabilation Nursing, 22(20–23), 39.

- Nalder, E., Fleming, J., Cornwell, P., & Foster, M. (2012). Linked lives: The experiences of family caregivers during the transition from hospital to home following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 13(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2012.4

- Newman, I., & Ridenour, C. (1998). Qualitative-quantitative research methodology: Exploring the interactive continuum. Carbondale. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Norup, A., Perrin, P. B., Cuberos-Urbano, G., Anke, A., Andelic, N., Doyle, S. T., Cristina Quijano, M., Caracuel, A., Mar, D., Guadalupe Espinosa Jove, I., & Carlos Arango-Lasprilla, J. (2015). Family needs after brain injury: A cross cultural study. NeuroRehabilitation, 36(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-151208

- Nott, M. T., Chapparo, C., & Baguley, I. J. (2006). Agitation following traumatic brain injury: An Australian sample. Brain Injury, 20(11), 1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050601049114

- Othman, H., Ludin, S. M., Saidi, S., & Awang, M. S. (2021). The needs of traumatic brain injury survivors’ caregivers and the implication required during the COVID-19 pandemic: Public health issues. Journal of Public Health Research, 10(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2205

- Oyesanya, T. O. (2017). The experience of patients with ABI and their families during the hospital stay: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Brain Injury, 31(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2016.1225987

- Oyesanya, T. O., & Bowers, B. (2017a). “I’m trying to be the safety net”: family protection of patients with moderate-to-severe TBI during the hospital stay. Qualitative Health Research, 27(12), 1804–1815. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317697098

- Oyesanya, T. O., & Bowers, B. (2017b). Managing visitors during the hospital stay: The experience of family caregivers of patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Family Nursing, 23(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840717697673

- Oyesanya, T. O., Loflin, C., Harris, G., & Bettger, J. P. (2021). “Just tell me in a simple way”: A qualitative study on opportunities to improve the transition from acute hospital care to home from the perspectives of patients with traumatic brain injury, families, and providers. Clinical Rehabilitation, 35(7), 1056–1072. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215520988679

- Pegg, P. O., Auerbach, S. M., Seel, R. T., Buenaver, L. F., Kiesler, D. J., & Plybon, L. E. (2005). The impact of patient-centered information on patients’ treatment satisfaction and outcomes in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(4), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.50.4.366

- Phyland, R. K., Ponsford, J., Carrier, S. L., Hicks, A. J., & McKay, A. (2021). Agitated behaviours following traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence by post-traumatic amnesia status, hospital setting and agitated behaviour type. Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(22), 3047–3067. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0257

- Ponsford, J., Janzen, S., McIntyre, A., Bayley, M., Velikonja, D., & Tate, R. (2014). INCOG recommendations for management of cognition following traumatic brain injury, part I: Posttraumatic amnesia/delirium. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 29(4), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000074

- Riley, G. A. (2007). Stress and depression in family carers following traumatic brain injury: The influence of beliefs about difficult behaviours. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215506071279

- Rotondi, A. J., Sinkule, J., Balzer, K., Harris, J., & Moldovan, R. (2007). A qualitative needs assessment of persons who have experienced traumatic brain injury and their primary family caregivers. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200701000-00002

- Russell, W. R., & Smith, A. (1961). Post-traumatic amnesia in closed head injury. Archives of Neurology, 5(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1961.00450130006002

- Sandel, M. E., & Mysiw, W. J. (1996). The agitated brain injured patient. Part 1: Definitions, differential diagnosis, and assessment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 77(6), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90306-8

- Schönberger, M., Ponsford, J., Olver, J., & Ponsford, M. (2010). A longitudinal study of family functioning after TBI and relatives’ emotional status. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(6), 813–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011003620077

- Schwandt, T. A. (1994). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publishing, 118–137.

- Schwartz, M. L., Carruth, F., Binns, M. A., Brandys, C., Moulton, R., Snow, W. G., & Stuss, D. T. (1998). The course of post-traumatic amnesia: Three little words. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences/Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques, 25(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100033709

- Silva-Smith, A. L. (2007). Restructuring life: Preparing for and beginning a new caregiving role. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840706297425

- Singh, R., Venkateshwara, G., Nair, K. P. S., Khan, M., & Saad, R. (2014). Agitation after traumatic brain injury and predictors of outcome. Brain Injury, 28(3), 336–340. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2013.873142

- Spiteri, C., Ponsford, J., Williams, G., Kahn, M., & McKay, A. (2021). Factors affecting participation in physical therapy during posttraumatic amnesia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 102(3), 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.024

- Stenberg, M., Stålnacke, B.-M., & Saveman, B.-I. (2020). Family experiences up to seven years after a severe traumatic brain injury-family interviews. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1774668

- Tam, S., McKay, A., Sloan, S., & Ponsford, J. (2015). The experience of challenging behaviours following severe TBI: A family perspective. Brain Injury, 29(7-8), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1005134

- Tate, R. L., Pfaff, A., & Jurjevic, L. (2000). Resolution of disorientation and amnesia during post-traumatic amnesia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 68(2), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.68.2.178

- Testa, J. A., Malec, J. F., Moessner, A. M., & Brown, A. W. (2006). Predicting family functioning after TBI: Impact of neurobehavioral factors. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 21(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200605000-00004

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Turner, B., Fleming, J., Cornwell, P., Worrall, L., Ownsworth, T., Haines, T., Kendall, M., & Chenoweth, L. (2007). A qualitative study of the transition from hospital to home for individuals with acquired brain injury and their family caregivers. Brain Injury, 21(11), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050701651678

- Verhaeghe, S., Defloor, T., & Grypdonck, M. (2005). Stress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14(8), 1004–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01126.x

- Weir, N., Doig, E. J., Fleming, J. M., Wiemers, A., & Zemljic, C. (2006). Objective and behavioural assessment of the emergence from post-traumatic amnesia (PTA). Brain Injury, 20(9), 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050600832684

- Whiffin, C. J., & Ellis-Hill, C. (2022). How does a narrative understanding of change in families post brain injury help us to humanise our professional practice? Brain Impairment, 23(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2021.14

- Whiffin, C. J., Ellis-Hill, C., Bailey, C., Jarrett, N., & Hutchinson, P. J. (2019). We are not the same people we used to be: An exploration of family biographical narratives and identity change following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(8), 1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1387577

- Wilson, A. D., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Manning, L. P. (2016). Using paired depth interviews to collect qualitative data. Qualitative Report, 21, 1549–1573. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2166