Abstract

Background: Physical activity interventions are an important adjunct therapy for people with severe to moderate and/or enduring mental health problems. Football is particularly popular for men in this group. Several interventions have emerged over the past decade and there is a need to clearly articulate how they are intended to work, for whom and in what circumstances.

Aims: To develop a theory-driven framework for a football intervention for men with severe, moderate and/or enduring mental health problems using a participatory realist approach.

Methods: A participatory literature review on playing football as a means of promoting mental health recovery with a realist synthesis. It included the accounts and input of 12 mental health service users and the contributions of other stakeholders including football coaches and occupational therapists.

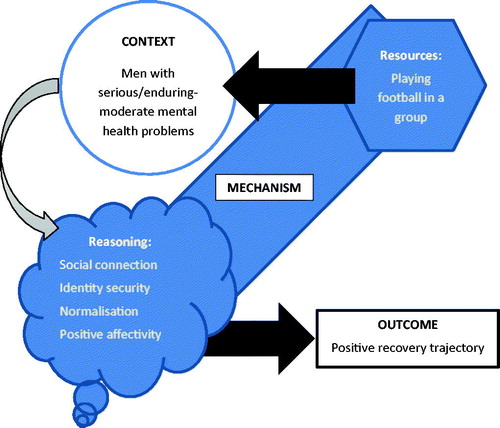

Results: Fourteen papers were included in the review. Analysis revealed that interventional mechanisms were social connectedness, identity security, normalising experiences and positive affectivity. These supported mental health recovery. Outcomes were moderated by social stigma and several interventional factors such as over-competitiveness.

Conclusions: The context mechanism outcome configuration framework for these interventions map well onto social models of mental health recovery and provide insight into how they work. This now requires testing.

Background

Physical activity-, sport- and recreation-based interventions are an increasingly important adjunct therapy for people with severe-to-moderate and enduring mental health problems (Fenton et al., Citation2017; Soundy, Roskell, Stubbs, Probst, & Vancampfort, Citation2015). Football interventions are particularly popular in the UK, especially among men, owing in part to their “gender congruence” (Curran et al., Citation2016; Friedrich & Mason, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Mcardle, Mcgale, & Gaffney, Citation2012; Spandler, Roy, & Mckeown, Citation2014). Several interventions have been developed and existing evidence suggests that football-based mental health interventions are broadly acceptable and can derive benefits such as: reducing stigma associated with clinical environments; reducing social isolation; improvements in physical health and provide opportunities for normalising social activity (Mason & Holt, Citation2012). These promising initial findings have been further reinforced in a recent literature review that suggests that that football can support mental health recovery for men with serious and/or enduring or moderate mental health problems because it is physically active, gender-congruent and socially inclusive (Friedrich & Mason, Citation2017a).

While empirical evidence is building for the potential value of football in supporting people with a mental health problem, there is a relative paucity of quantitative studies measuring effectiveness (Friedrich & Mason, Citation2017a). There are several reasons for this. Firstly, football for mental health interventions are still in their infancy with a host of approaches being adopted with a range of participant groups. Robust interventional and evaluative strategies are yet to be developed. Secondly, “football for mental health” interventions – like other physical activity initiatives – are complex with multiple components, potential confounders, mediators and moderators. Knowing what these are, explaining them and/or controlling for them is challenging. Finally, while interventions tend to focus on improving mental health, the intended outcomes of interventions are generally multi-dimensional and, as a consequence, interconnected in a complex causal chain. These challenges point to a need to better theorise what football for mental health interventions are seeking to achieve, how they try to do it, what are the intended and unintended outcomes for whom and in what circumstances. More explicit and coherent programme theories of football for mental health interventions are required to better inform intervention development in this growing, complex and sensitive area.

Aims

The aim of the project was to help develop a theory-driven locally relevant football intervention for men with moderate to severe mental health problems. This would be achieved through a focussed systematic literature review and consultation with players and stakeholders. Its purpose was to establish what types of interventions, models of delivery and interventional components “work” for the subject group and what factors moderate optimisation. This was achieved through a collaboration between researchers, mental health and physical activity professionals and service users/players and was informed by the UK’s Medical Research Council’s complex intervention development guidance (Craig et al., Citation2006). In particular, the guidance was used to help establish what mechanisms underscore football-based interventions and to build a theory-driven intervention that would be suitable for piloting. As such, the project sought to develop a detailed research-informed, co-created programme theory using a realist framework (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, Citation2004).

Methods

A mixed methods approach was used in the study. Firstly, a focussed realist review of the evidence on the use of football as a mental health intervention was conducted. Secondly, a consultative exercise with a range of stakeholders including mental health providers and professionals, and local football community trusts was undertaken. Finally, public and patient involvement (PPI) with a range of mental health service users was used to establish what was feasible, acceptable and desirable for a mental health intervention based on football. Taking each one in turn:

Focussed systematic realist review

The review adopted a realist approach to unearth and refine theories of how football for mental health interventions are expected to work for men with serious mental health problems in particular contexts and circumstances. As such, the review is reported according to RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) guidelines (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, Citation2013).

Initial scoping identified a core base of interventions that had been subject to some form of evaluation or explicit programme design process. With a small base we pursued all possible intervention development and evaluative studies regardless of scientific quality. Scientific databases Medline, CINAHL via EBSCO, Web of Science and PsychInfo were searched using a standard PICO format (Appendix A). The eligibility criteria were:

Participants were adult men (aged 18+) with moderate-to-severe and/or enduring mental health conditions.

Participating in/playing football or soccer as the intervention.

Outcomes focused on subjects’ mental health/wellbeing with or without other outcomes.

All study types including reviews, effectiveness studies, intervention development studies, evaluative case studies and qualitative work.

Published in English from 1990 to 2016.

Excluded studies were those where:

Participants <18 years or elite athletes, those with dementia or mild/low-level mental health problems.

Interventions involving watching football only, using football metaphors in talking therapies or the use of football clubs as a setting for a more general physical activity intervention.

Outcomes focused exclusively on physical health.

Screening at title and abstract was conducted by a single researcher in the first instance; at full text by two researchers independently.

Limited relevant initial search results were supplemented by Google searches for relevant interventions and grey publications. Citations from included studies were followed-up for additional references. Authors of evaluations of the Coping Through Football intervention were contacted directly and consulted about emerging programme theories.

A standardised data extraction template was produced and tested by the lead author and applied to the selected studies by three members of the research team. Ten per cent of selected papers were checked for extraction accuracy and consistency. Analysis was guided by thematic trends emerging through reported study findings and consultations and clustered according to their place within a context mechanism outcome configuration (CMOc) (Dalkin, Greenhalgh, Jones, Cunningham, & Lhussier, Citation2015). This framework was used to help elucidate theories implicit and explicit in the design of football for mental health interventions. Analysis integrates the findings of the literature and the consultative work.

Consultation with professionals

Mental health professionals involved in supporting mental health service users were consulted along with football coaches/physical activity practitioners who ran and/or organised sessions (). This was done to explore what they did to promote positive outcomes for players and to establish what worked well or not so well in their experience. Prior to the project and in scoping the literature, it was evident that football programmes for people with mental health problems had been in operation regionally and nationally for around a decade. The project sought to capture the tacit knowledge and expertise gained among people working in such services in order to inform “best practice” in the delivery, organisation and evaluation of such projects. The programmes in place included football sessions that had started as “kick abouts” in hospital grounds and had grown to formal affiliated teams in mental health leagues and play/training sessions that had been driven by community arms of professional football clubs. Consistent across all programmes were regular training sessions, team structures and occasional external competition. Consultation focused on the overall value of football for mental health recovery; referral and access processes; retention and engagement; the valued components of interventions; the football environment and ethos; stigma; and the acceptability of different wellbeing/recovery scales.

Table 1. Three “clusters” of participants in the consultative exercise, including PPI participants.

Public and patient involvement

Mental health service users/players from three local NHS Trust areas were consulted to share their experiences and help identify “what works” for them in the management, delivery and broader context of their play. This phase of the work purposively sought “experts by experience” (Noorani, Citation2013) and adopting the participatory principles and practices of national PPI guidance (INVOLVE, Citation2012).

Data synthesis and analysis: The different components of the project were carried out simultaneously so that emerging themes from the review could be cross-referenced and developed into a single narrative. Analysis and synthesis was informed by the realist, participatory methods in systematic reviews developed by Harris et al. (Harris, Croot, Thompson, & Springett, Citation2016).

Results and discussion

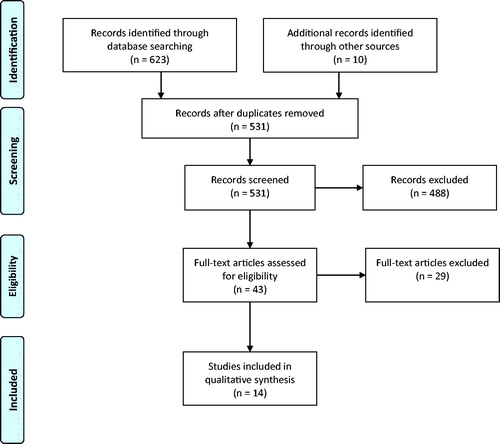

Fourteen papers were included in the review from 11 interventions (). A summary of the components and main findings of the included studies are summarised in .

Figure 1. PRIMSA flow diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman,Citation2009).

Table 2. Included studies’ characteristics and main findings.

An outline of common interventional components highlighted in the review is reported in using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework (Hoffmann et al., Citation2014). These represent commonly cited components derived from programmatic strategies across multiple sites.

Table 3. TIDIieR checklist of interventional components (Hoffmann et al.,Citation2014).

Included studies made use of pre- and post-test (Battaglia et al., Citation2013), longitudinal (Henderson, O’Hara, Thornicroft, & Webber, Citation2014; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2013; Time to Change, Citation2013 and cross sectional designs (London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2015; McElroy, Evans, & Pringle, Citation2008). Qualitative research dominated with four studies exclusively using such methods (Brawn, Combes, & Ellis, Citation2015; Derby County in the Community, Citation2010; Magee, Spaaij, & Jeanes, Citation2015; Mason & Holt, Citation2012). There was one small RCT reported (Battaglia et al., Citation2013) one intervention development description (Edwards, Citation2006) and six studies adopting mixed methods. One evaluation report made extensive use of a range of methods including documentary analysis, routine data analysis, interviews with stakeholders and players and analysis of service user feedback forms (Douglas & Carless, Citation2012). This profile of studies reinforces Friedrich and Mason’s observation that quantitative effectiveness reviews are not currently possible in this field (Friedrich & Mason, Citation2017a). As such, careful extraction of programme theories is a first step towards testable interventional design (Craig et al., Citation2006).

Theoretical framework for intervention design

Programme theories about interventions were largely implicit. Several different contexts were explored, for example, football for men with a diagnosis of schizophrenia was explicitly examined in one study (Battaglia et al., Citation2013); others included participants with a range of mental health conditions from mild to severe (Brawn et al., Citation2015; Derby County in the Community, Citation2010); most explored interventions working with men with generally described serious mental illness (Darongkamas, Scott, & Taylor, Citation2011; Douglas & Carless, Citation2012; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2015; Mason & Holt, Citation2012). Overall, specific conditions were considered marginal to other factors that connected participants; namely, high incidence of social isolation/detachment, felt stigma, enduring loneliness, low social contact, low self-esteem and confidence and low motivation. Players were “in the same boat” in multiple ways.

Outcomes of interventions were rarely objectively measured using recognised, validated scales. Player self-report of physical health, wellbeing, mood, stigma and discrimination, isolation and engagement with services are some examples of outcome measures. This reflects the different goals, local contexts, maturity, complexity and capacity of interventions. In consultation, stakeholders referred to a desire to find and use a validated and acceptable tool that could measure mental health recovery in their interventions. Both players and coaches identified problems with both the content and the administration of tools such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) in the context of a mental health interventions; they were keen to avoid replicating elements of the clinical environment and reinforcing any associated stigma.

The multi-faceted ambitions of interventions also led to a lack of clarity in the articulation of the intended outcomes of interventions. This meant many programmes were not in a position to outline how interventions were expected to deliver outcomes. Examples of outcomes included in interventions were: reducing self and social stigma, improving confidence and self-esteem, developing feelings of belonging and community, developing teamwork and encouraging mastery.

Taken together, the literature review and the consultation revealed ambiguity about preferred primary outcome measures. Social models of recovery were commonly adopted (Brawn et al., Citation2015; Douglas & Carless, Citation2012; Henderson et al., Citation2014; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2015; Time to Change, Citation2013) and football was seen as part of a recovery journey for individuals with complex psychiatric and social needs.

The mechanisms of football intervention worked in four interrelated ways: 1 Bringing about social connection; 2. Promoting identity security; 3. Enhancing normalisation; and 4. Encouraging positive affectivity. These are represented in the CMOc model in and explained in more detail below. The mechanism’s resource was playing football in a group but this was often conflated with the programmatic strategy of the intervention () (Dalkin et al., Citation2015). As demonstrates, programmes were multi-faceted with several preferred characteristics of delivery. This is not to say, however, that these facets are mechanisms in themselves. Following Weiss’ argument, mechanisms are not the programme service but the response it triggers from service users (Weiss, Citation1997). These require reasoning on the behalf of the user.

Social connection

Changes to participant reasoning were related to how activity positively connected players to others in the group (Brawn et al., Citation2015; Darongkamas et al., Citation2011; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2015; Magee et al., Citation2015; McElroy et al., Citation2008; Time to Change, Citation2013). This connection triggered positive feelings and practices of genuine friendship, camaraderie, confidence, reciprocity, mutual support, belonging and community (Brawn et al., Citation2015; Darongkamas et al., Citation2011; Derby County in the Community, Citation2010; Douglas & Carless, Citation2012; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013). The mechanism of sharing “connection stories” between players encouraged progress in recovery (Brawn et al., Citation2015). The cumulative benefits of social connection encouraged on-going participation which in turn delivered physical health benefits (actual or perceived) that could elevate confidence, a sense of mastery and self-esteem. Connections also provided social support during periods when mental health deteriorated.

Identity security

Mechanisms of change were rooted in players’ opportunity to connect to their younger, mentally well self through football; a masculine and “accepted” culturally powerful practice. Players often reported a history of an interest in football and connected those positive experiences in their reasoning for engagement. It could be a “hook” to spark initial interest and an ongoing motivating factor in a reconceptualization of the self as competent, skilled and active (London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013; Magee et al., Citation2015; Mason & Holt, Citation2012). Developing a positive sense of self and a secure identity through football promoted recovery and countered self- and socially-stigmatising narratives.

Normalisation

Football added “normal” routine, structure and a sense of purpose to players’ lives (Derby County in the Community, Citation2010; Henderson et al., Citation2014; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013). These factors were noticeably absent prior to participation. Bringing back routine and purpose to daily life and getting players away from clinical settings promoted recovery. For some, football was a stepping stone to other mainstream, normalised practices such as employment and training, although this was recognised as an upstream and sometimes distant recovery goal for many (Darongkamas et al., Citation2011; London Playing Fields Foundation, Citation2010, Citation2013; Mason & Holt, Citation2012).

Positive affectivity

Football was fun (Darongkamas et al., Citation2011; Magee et al., Citation2015; Mason & Holt, Citation2012). Players cited positive feelings and emotions during play, tournaments, kick-abouts, celebrations and when mingling before and after sessions. Affective display in the form of, for example, celebrating goals, shouting support to fellow players, clapping and cheering was also positively experienced and promoted mental wellness. Showing emotion such as “letting off steam” was also valued, within certain parameters (Magee et al., Citation2015; Mason & Holt, Citation2012).

It is important to note that these mechanisms were mutually reinforcing and interdependent but importantly shaped by a series of intervening factors. Many of these related to the programmatic strategy of the intervention but some were broader, social systematic moderators over which players and programmes had no control such as the social stigma of serious mental illness (Magee et al., Citation2015). This systemic factor was problematic in the development of “mental health” teams or leagues because labelling could reinforce self-stigma and moderate identity security and social connectedness. Other moderators related to the resource itself: playing football is competitive; team play and tournaments produce winners and losers. There is also the potential for aggression and violence. Football as a mechanism of change was moderated when it violated the ethos of respectful play, mutual encouragement, player unity and responsibility (Magee et al., Citation2015). To mitigate these effects, many programmes reported the importance of the skills and training of coaches; for example, the need for empathy, understanding, approachability and respectfulness as well as technical ability (Douglas & Carless, Citation2012; Edwards, Citation2006; Magee & Jeanes, Citation2013; Mason & Holt, Citation2012). Including health professionals in football games and training may help “level the playing field” and break down the hierarchical relationship between service deliverers and users. In addition, entering competitions/tournaments required consideration of the teams’/players’ needs and stage in recovery and had to reflect the practical limitations of many ().

Discussion

This review sought to develop a framework for the development of a local football intervention for men with serious/enduring to moderate mental health problems. It did so in the context of the growing popularity of physical activity interventions for promoting good mental health and the involvement of many football clubs, sport governing bodies, mental health charities and mental health service providers developing their own programmes.

This review was limited by an overall small evidence base. These limitations have been noted in previous work (Friedrich & Mason, Citation2017b). The quality of the evidence base was generally low (indicated by several grey publications) but with some robust in-depth qualitative studies that begin to identify programme theory. Notable omissions from the evidence base were studies with control or comparison groups, research with people who have attended and dropped out and people for whom the interventions were intended but did not attend, notably, women. The consultation also reflected these omissions.

Importantly, the review helps fill a critical gap in understanding of what works for whom, how and in what circumstances. Such syntheses of evidence and theory have not been attempted in this field and are rare in the physical activity field in general, despite a broad movement towards mental health programme development in the UK. Engagement by service users and deliverers is particularly absent, despite delivering several advantages in terms of theory, intervention development and refinement and ethical research practice (Crawford et al., Citation2011; Harris et al., Citation2016).

This analysis pays particular attention to mechanisms of football interventions. In so doing it clarifies the resources and reasoning at play that combine to promote recovery. These findings now need to be tested. The question of outcome measures continues to represent a serious challenge to this field (Connell, O’Cathain, & Brazier, Citation2014). Recent developments in bespoke objective measure development and tools hold great promise (Keetharuth et al., Citation2018) and we must continue to invest in answering questions about how tools should be administered, by whom and in combination with what other measures and tools (Crawford et al., Citation2011).

The CMOc framework devised fits clearly within well-established models of mental health recovery such as the CHIME framework which emphasises connectedness, hope, identity, meaning in life and empowerment (Leamy, Bird, Boutillier, Williams, & Slade, Citation2011). Crucially, the present paper clearly articulates how football as a mental health intervention for men “turns the dimmer switch” (Dalkin et al., Citation2015) towards recovery and how identified moderators can dim that light. Attention to programmatic strategy and content is essential in this regard. As noted, however, some moderators relate to social, structural and systemic factors over which players and organisers have little, if any, control, particularly the stigma of mental illness. In the development of this model, it is important not to ignore these wider determinants and continue to develop realist methods and understanding that connect interventional experience with structural parameters (Dalkin, Williams, Burton, & Rycroft-malone, Citation2018).

In summary, whilst the current review cannot claim to represent a universal theoretical framework for football for mental health interventions in general, it provides a timely and clear articulation of what such interventions are intending to achieve, how, for whom and in what circumstances.

Ethics

This project was a participatory review for intervention development. Consultees were not research subjects. Rather, consultees offered their experiential expertise to help construct a locally-relevant and theoretically robust physical activity intervention. Please see the methods section for more detail. The ethical principles and practices adhered to were those identified by the UK Public and Patient Involvement advisory body: NIHR INVOLVE http://www.invo.org.uk/ and the consultation was funded and monitored by NIHR Research Development Service Yorkshire and Humber.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to all the contributors to this work, particularly the players. In addition, Jack Matthews, Jason White and Sam Firth of Sheffield and Hallamshire County Football Association; Michele Hayden and Emma Davidson of the Yorkshire Sport Foundation and Trudi Race of the Rotherham United Community Trust have assisted greatly in the project. Thanks go to Rotherham United, Barnsley Recovery College and Sheffield Hallam University for providing facilities to conduct consultation events. We are also grateful to the advice and guidance of Bettina Friedrich and Oliver Mason of UCL who provided helpful reflections on this emerging area of practice.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Battaglia, G., Alesi, M., Inguglia, M., Roccella, M., Caramazza, G., Bellafiore, M., ⋯ Palma, A. (2013). Soccer practice as an add-on treatment in the management of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 595–603. doi:10.2147/NDT.S44066

- Brawn, P., Combes, H., & Ellis, N. (2015). Football narratives : Recovery and mental health. Journal of New Writing in Health and Social Care, 2(1), 30–46.

- Connell, J., O’Cathain, A., & Brazier, J. (2014). Measuring quality of life in mental health: Are we asking the right questions? Social Science & Medicine, 120, 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.026

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Health, P., Unit, S., Michie, S., … Petticrew, M. (2006). Developing and evaluating complex interventions : New guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Crawford, M. J., Robotham, D., Thana, L., Patterson, S., Weaver, T., Barber, R., … Rose, D. (2011). Selecting outcome measures in mental health: The views of service users. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 20(4), 336–346. doi:10.3109/09638237.2011.577114

- Curran, K., Rosenbaum, S., Parnell, D., Stubbs, B., Pringle, A., & Hargreaves, J. (2016). Tackling mental health: The role of professional football clubs. Sport in Society, 437, 1–11. doi:10.1080/17430437.2016.1173910

- Dalkin, S. M., Greenhalgh, J., Jones, D., Cunningham, B., & Lhussier, M. (2015). What’s in a mechanism ? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implementation Science, 10(49), 1–7. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x

- Dalkin, S., Williams, L., Burton, C. R., & Rycroft-Malone, J. (2018). Exploring the use of Soft Systems Methodology with realist approaches : A novel way to map programme complexity and develop and refine programme theory. Evaluation, 24, 84–97. doi:10.1177/1356389017749036

- Darongkamas, J., Scott, H., & Taylor, E. (2011). Kick-starting men’s mental health: An evaluation of the effect of playing football on mental health service users’ well-being. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 13(3), 14–21. doi:10.1080/14623730.2011.9715658

- Derby County in the Community. (2010). Derby County in the Community Winning Mentality – Football sessions for people with mental health issues Project Evaluation, November 2010.

- Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2012). Bristol active lives project final evaluation report 2009–2012.

- Edwards, A. (2006). Derwent Valley Rovers football club. Mental Health Review, 11(2), 38–40. doi:10.1108/13619322200600020

- Fenton, L., White, C., Gallant, K. A., Gilbert, R., Hamilton-Hinch, B., Lauckner, H., … Hutchinson, S. (2017). The benefits of recreation for the recovery and social inclusion of individuals with mental illness: An integrative review. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/01490400.2015.1120168

- Friedrich, B., & Mason, O. J. (2017a). “What is the score ?”. A Review of Football-Based Public Mental Health Interventions. Journal of Public Mental Health, 16, 144–158. doi:10.1108/JPMH-03-2017-0011

- Friedrich, B., & Mason, O. J. (2017b). Evaluation of the Coping through football project : Physical activity and psychosocial outcomes evaluation. Open Public Health Journal, 10(1), 276–282. doi:10.2174/1874944501710010276

- Harris, J., Croot, L., Thompson, J., & Springett, J. (2016). How stakeholder participation can contribute to systematic reviews of complex interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(2), 207–214. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205701

- Henderson, C., O’Hara, S., Thornicroft, G., & Webber, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and mental health: The Premier League football Imagine Your Goals programme. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 26(4), 460–466. doi:10.3109/09540261.2014.924486

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., … Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348(Mar07 3), g1687–g1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687

- INVOLVE (2012). Briefing notes for researchers: Public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Retrieved from www.involve.nihr.ac.uk

- Keetharuth, A. D., Brazier, J., Connell, J., Bjorner, J. B., Carlton, J., Taylor Buck, E., … Barkham, M. (2018). Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL) : A new generic self-reported outcome measure for use with people experiencing mental health difficulties†. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 42–49. doi:10.1192/bjp.2017.10

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health : systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 445–452. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- London Playing Fields Foundation (2010). Coping through football. Evaluation report. Retrieved from www.copingthroughfootball.org

- London Playing Fields Foundation (2013). Coping through football. Evaluation report. Retrieved from www.copingthroughfootball.org

- London Playing Fields Foundation (2015). Coping through football. Evaluation Report. Retrieved from www.copingthroughfootball.org

- Magee, J., & Jeanes, R. (2013). Football’s coming home: A critical evaluation of the Homeless World Cup as an intervention to combat social exclusion. International Review of the Sociology of Sport, 48(1), 3–19. doi:10.1177/1012690211428391

- Magee, J., Spaaij, R., & Jeanes, R. (2015). “It’s Recovery United for Me”: Promises and Pitfalls of Football as Part of Mental Health Recovery. Sociology of Sport Journal, 32(4), 357–376. doi:10.1123/ssj.2014-0149

- Mason, O. J., & Holt, R. (2012). A role for football in mental health: The Coping Through Football project. Psychiatrist, 36(08), 290–293. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.111.036269

- Mcardle, S., Mcgale, N., & Gaffney, P. (2012). A qualitative exploration of men’s experiences of an integrated exercise/CBT mental health promotion programme. International Journal of Men’s Health, 11(3), 240–257. doi:10.3149/jmh.1103.240

- McElroy, P., Evans, P.A., & Pringle, A. (2008). Sick as a parrot or over the moon: An evaluation of the impact of playing regular matches in a football league on mental health service users. Practice Development in Health Care, 7(1), 40–48. doi:10.1002/pdh

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Noorani, T. (2013). Service user involvement, authority and the “expert-by-experience” in mental health. Journal of Political Power, 6(1), 49–68. doi:10.1080/2158379X.2013.774979

- Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2004, January). Realist synthesis – an introduction. ESRC Research Methods Programme (pp. 1–46). Retrieved from http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/180102/

- Soundy, A., Roskell, C., Stubbs, B., Probst, M., & Vancampfort, D. (2015). Investigating the benefits of sport participation for individuals with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Psychiatria Danubina, 27(1), 2–13. doi:10.1155/2015/261642

- Spandler, H., Roy, A., & Mckeown, M. (2014). Using football metaphor to engage men in therapeutic support. Journal of Social Work Practice, 28, 229–245. doi:10.1080/02650533.2013.853286

- Time to Change (2013). Imagine Your Goals. Improving mental health through football. Retrieved February 25, 2019, from https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/sites/default/files/imagine-your-goals-improving-mental-health-through-football.pdf

- Weiss, C. (1997). Theory-based evaluation: past, present, and future. New directions for evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., Buckingham, J., & Pawson, R. (2013). RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Medicine, 11, 21. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-21

Appendix A

All databases had the following limits applied to the searches:

English language only

Published during or after 1996