Abstract

Background

Men at risk of suicide often face difficulties with finances, employment, or housing, yet support services are usually psychologically based. This study evaluated the Hope service which provides integrated psychosocial support alongside practical, financial and specialist advice.

Aims

To examine how the Hope service supports men at risk of suicide and factors that influence its impact and usefulness.

Methods

Twenty-six qualitative interviews with 16 service users, six Hope staff, two specialist money advice workers funded to work for Hope and two NHS referral staff, thematically analysed.

Results

The Hope service provided an essential service for men at risk of suicide, with complex needs including addiction, job loss, homelessness, debt, relationship-breakdown and bereavement who often would otherwise have fallen through service provision gaps. Working in a person-centred, non-judgemental way elicited trust and specialist advice tackled problems such as housing needs, debt, benefit claims and employment, enabling men to regain a sense of control over their lives. Some men shared histories of abuse, for which specialist counselling was hard to access.

Conclusions

Hope provides an effective integrated support package for suicidal men. Funding for services like Hope are important to tackle structural issues such as homelessness and debt, alongside emotional support.

Introduction

Numerous studies have demonstrated relationships between debt and poor mental health (Richardson et al., Citation2013) and there is clear evidence that financial recessions are associated with increases in suicide rates, with other factors such as debt, housing and employment issues, relationships, and alcohol or drug misuse possibly contributing (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Gunnell & Chang, Citation2016; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). People with debt and financial problems are twice as likely to think about suicide than those not in financial difficulty (Meltzer et al., Citation2011). In a study of coroners' records of 286 people who died by suicide in 2010–2011, financial/employment-related issues contributed to 13% of suicide deaths (Coope et al., Citation2015). Men can be particularly affected, with recession-associated rises in suicide observed in male mental health patients and the male general population, with particular risk for those in mid-life (Ibrahim et al., Citation2019).

Men accounted for three-quarters of registered suicide deaths in England and Wales in 2020, a trend consistent since the mid-1990s (ONS, Citation2021), and a pattern repeated in other high-income countries where three times as many men die of suicide than women do (WHO, Citation2014). Men aged 45–64 years have the highest age-specific suicide rates (ONS, Citation2021) and in 2018 middle-aged men (40–50 years) accounted for a third of all suicides in England (ONS, Citation2019). Factors that might contribute to these high figures include beliefs and behaviours related to cultural perceptions of masculinity, reluctance to disclose distress, sense of loss of control, shame, isolation, loss, grief, separation from children and difficulties in seeking professional help (Chandler, Citation2019a, Citation2021; Cleary, Citation2017; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019; Wyllie et al., Citation2012).

Suicide support services are often focussed on psychology and fewer provide a broad range of support needs including financial advice (Chandler, Citation2019b, Citation2021), and specifically target men (Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). Support and targeted interventions for people with financial difficulties may reduce risk of suicide (Ibrahim et al., Citation2019), and it has been proposed that collaborations between mental health support and debt advice be developed, alongside associated research to understand the effectiveness of this (Gunasinghe et al., Citation2018). There are few qualitative studies that focus on the lived experiences and perspectives of suicidal men, or evaluative research that analyses the effectiveness of suicide prevention interventions for middle-aged men (Chandler, Citation2019a; Chopra et al., Citation2022; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). As this cohort experiences the highest rates of suicide within high-income countries, there is a recognised need to develop and evaluate interventions designed to reduce male suicide (Struszczyk et al., Citation2019; Wyllie et al., Citation2012). This article contributes to these research gaps to illustrate how structural factors such as housing, finance and employment issues can be tackled in suicide interventions to support men (Chandler, Citation2021), alongside the implementation of community-based interventions (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Wykes et al., Citation2021) that combine practical advice and psychological support delivered by voluntary organisations (Saini et al., Citation2020).

The HOPE intervention (original HOPE acronym: Help fOr People with money, Employment, benefit or housing problems) was developed to provide psychosocial and practical advice in relation to money, employment and housing problems (Barnes et al., Citation2017), and a pilot randomised trial found it to be feasible and acceptable (Barnes et al., Citation2018). The HOPE intervention was originally designed for men and women over 18 (Barnes et al., Citation2017), it was then implemented and further developed by Second Step, a mental health charity, commissioned in the Bristol, North Somerset and Gloucestershire area, who named the service Hope (without the acronym). Following the Five-Year Forward View for Mental Health (Mental Health Taskforce, Citation2016), local health systems with the highest suicide rates were given funding to develop suicide prevention services. The commissioning of Hope in 2018 through these funds, directed the intervention towards those most at risk of suicide, men aged 30–64 (ONS, Citation2019). A mixed methods article outlines the impact of the Hope service for men at risk of suicide (Jackson et al., Citation2022), indicating positive outcomes in terms of reducing suicidal ideation and improving financial self-efficacy. This qualitative research aimed to evaluate the acceptability and usefulness of Hope from service user, staff and referrer perspectives, to understand how the Hope service supports men at risk of suicide and the factors that influence its impact.

The Hope service

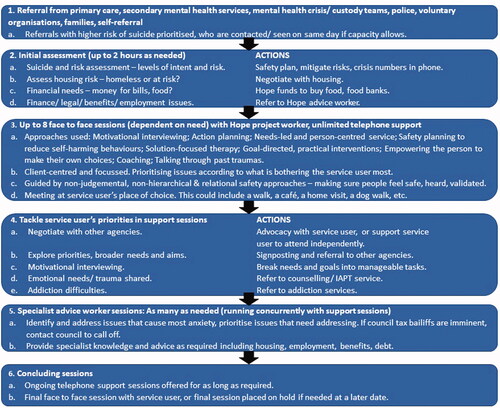

The Hope service provides psychosocial and practical support for men aged 30–64 who are at risk of suicide, advising them in relation to any money, employment, benefit, or housing problems they may identify, alongside referring to other specialist services. Many of the men referred to the Hope service have attempted suicide or had suicidal/self-harming thoughts and feelings. Referrals can be made from statutory and voluntary organisations, as well as self-referrals. The service accepts men with addiction problems, mental health diagnoses (excluding severe active psychosis) and those who are homeless. illustrates how Hope staff work with service users from referral through to the completion of sessions. overviews the role of Hope support workers and Hope advice workers.

Table 1. Staff roles and training.

Methods

Design

Semi-structured interview study with Hope service users, Hope project workers, advice workers and managers, and NHS staff who referred to the Hope service. The study was approved by the University of Bristol Faculty Research Ethics Committee reference 99982, and Health Research Authority IRAS 281906, reference 20/HRA/3306.

Recruitment

A Hope project worker facilitated recruitment of service users, making initial contact, supplying participant information sheets to those interested in taking part, and arranging times for interviews with researchers (MF and JB). Service user participants were purposefully sampled by age, ethnicity, mode of referral, level of debt, range of project workers they interacted with, and engagement with the service. For staff, a Hope manager sent an invite and information sheet to Hope project and advice workers via email, asking them to contact researchers directly if they were interested in being interviewed. The Hope manager also contacted appropriate NHS referral team leads and asked them to contact their staff with our invite and information sheet; referral staff were asked to contact researchers directly to take part. Sampling for service users was guided by information power, where data was analysed and assessed according to study aims as data collection progressed, completing data collection as fewer new themes arose through the data (Malterud et al., Citation2016). For staff and referrers, we adopted a pragmatic approach, inviting all relevant staff to be interviewed and when we had interviewed over 50% of staff group members, and no further staff responded to our invitations, we completed our sampling.

Interview and consent process

All interviews were conducted remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic by MF and JB, qualitative researchers with experience of interviewing about sensitive topics. Participants were offered a choice of using the phone or a secure online video conferencing system. A verbally recorded consent process preceded interviews. Interviews were based on a topic guide (see Appendix A), audio-recorded, transcribed, anonymised and checked for accuracy. A protocol for the emotional safety of service users was implemented, ensuring that service users had access to appropriate support from a Hope project worker as needed after an interview. Service users received £20 to compensate them for their time, staff took part in interviews in their working time and were not additionally compensated.

Analysis

A thematic analysis approach was used, coding and analysing patterns and themes across the dataset using the framework method (Gale et al., Citation2013). MF and JB jointly developed an initial coding framework, and double coded a sample of transcripts (12%). The framework was then agreed, revised and applied across the full dataset. Members of the study team met regularly to discuss analysis. outlines this analytic framework, specific codes and example quotes.

Table 2. Analytic framework, specific codes and example quotes.

Patient and public involvement

Two former Hope service users advised us throughout the study, providing guidance on recruitment, information sheets, interview topic guides, and support for service users. They joined project management meetings and discussed analysis and write up and were invited to be co-authors of this article. One person accepted and reviewed and commented on this article.

Results

Twenty-six qualitative interviews were conducted with 16 service users, six Hope staff, two advice workers funded to work for Hope and two NHS referral staff. outlines characteristics of interviewees. Generally, there was consensus between staff and service users perspectives across the data set and themes are reported in the results using both data sources.

Table 3. Interviewee characteristics.

The Hope service – engaging with unmet needs

People’s circumstances when first talking with Hope included suicidal attempts, suicidal feelings and thoughts, loss of employment, accident/injury at work, homelessness, problems with addiction (alcohol, drugs, gambling), bereavement, debt, problems with welfare benefits, legal issues, custody battles and access to their children, loss of relationship/relationship breakdown, isolation and criminal injunctions. Many people faced a combination of these issues, which escalated and compounded difficulties, sometimes contributing to feeling loss of control. Participants described problems in accessing the support they needed:

I ran away and I went into woods and tied a knot yeah with socks and stuff and clothes I had and tried to hang myself. It was really, really bad and it was nasty and I didn’t have anyone to support me and I went to a hospital on a few occasions and I was in A&E and things and I had a team come and see me and they basically say to you “you’re not bad enough to be admitted to the psychiatric unit or anything like that. We have to refer you back to your GP, thank you very much… you’re safe, your drugs have worn off that you took, see you later” and that was it. And I had a GP ringing me the next day “oh we’ll refer you to (CBT/counselling provider) they’ll speak to you within a week” and then they say to you “oh there is a seven to 10 month waiting list”. (Service user 19)

Whilst the interview questions did not specifically ask about Hope’s focus on supporting men, some service users and staff spoke of the service having qualities that created a space in which men felt comfortable with disclosure and discussion, where they were able to express themselves uninhibited by the norms and pressures associated with masculinity:

I mean it takes a lot for a bloke to stick his hand out and say I need help. (Service user 13)

Creating a supportive space

The Hope service starts with an initial assessment session (see ) to enable an understanding of the problems being experienced by the service user and the type of support that might be needed. Staff described the process of letting service users direct this, asking them what they felt needed addressing first. Key priorities included a suicide risk assessment (which Hope project workers were trained in) and urgent housing needs:

I was homeless in me car…. I’m full of anxiety and I’m hiding, so I’m in mask [COVID-19] and sunglasses and I walk straight across [to Hope services], sign the piece of paper … within half an hour I was in the Travelodge [hotel]. (Service user 13)

Where service users were experiencing intense suicidal feelings, repeated and planned phone calls by a project worker could provide an “anchor”. Having a chance to talk about suicidal feelings could make a difference: “They’ve got that out, they’ve expressed it, and it does really help” (Staff 01). Focussing on major practical issues (e.g. imminent homelessness, financial difficulties) could enable people to regain a sense of control, helping to reduce risk of harm:

“You find that when people have more control over what’s going on with them and they feel sort of more supported and less overwhelmed… their risk of suicide is going to be decreased and that’s the aim, really” (Staff 06).

Four service users specifically stated that Hope’s services had saved their life:

I think that the Hope project saved my life and it was absolutely amazing and I couldn't ask for a better service (Service user 19)

Several service users explained that they knew they could contact their project workers in times of need. Characteristics of Hope sessions that were instrumental in creating a supportive environment were described by service users: time and space to say and express what was needed without feeling timebound; being “non-judgemental”, “creating a bond”, “trusted”, “safe”, “fantastic listener” and providing “reassurance”. Service users described a sense of “you felt you were in control… not somebody controlling you”. This could enable men to share thoughts, feelings and experiences that they had not spoken about before. Some described a relationship, that was in some ways better and beyond friends and family, as they could say what was needed without concern, worry or judgement.

Specialist advice services

Hope project workers supported service users to identify which issues were of most importance to them, prioritising and breaking down complex problems into a series of achievable steps. Where Hope project workers identified that service users would benefit from specialist advice, they would refer them to Hope advice workers (), with project workers continuing to provide psychosocial support as needed. The combination of specialist advice and emotional support made the Hope service distinctive:

It’s quite unique as well in the fact that – unlike counselling – we can speak with them throughout the week and we have phone calls with them… also what the counsellor can’t do is support them with rent or support them with understanding child visitation or understanding what a divorce means or debt. (Staff 7)

Having immediate access to funded advice workers was particularly important as referral to external advice organisations would have meant lengthy waiting lists. Advice workers could provide expert knowledge which helped service users understand the financial, debt or employment issues they faced. Sometimes injustices had occurred, which could either be challenged, or discussed and come to terms with, in ways that the person could manage:

They stopped my [benefits] money and that’s when the depression starts hitting you, it starts coming in very fast…. [the Hope advice worker] done one interview with me, and he spotted how wrong they [the welfare benefit assessors] were on everything and he sorted everything out for me which was great. He got me what I was entitled to. (Service user 16)

Managing debts, benefit appeals and increasing income where people did not have money for rent, food and bills was part of the advice workers role. They were funded to work with Hope service users until their problems were resolved, they were not limited in the number of sessions that they could give people. Advice workers had flexibility to engage with service users long term and they described how this enabled them to resolve issues as needed. In addition, Hope project workers could provide emotional support and advocate on behalf of service users, supporting them in attending appointments, which could have a major impact on positive outcomes:

Without our advocacy, we know without a shadow of a doubt that these men would be evicted. So we will then become the negotiator on their behalf, with the housing officer or the rent management team to, essentially, prevent eviction. So we’ve done that for many, many, many of our men and that’s normally picked up immediately. (Staff 2)

As time progressed, some men felt empowered to go on and represent themselves.

Addiction

Referrals and signposting to other services is a key part of Hope’s support package. For example, the Hope service worked alongside specialist addiction services, receiving referrals from them, and referring people onto addiction services.

My life could be totally different now, without being referred to the Hope service, I wouldn’t have been referred to the [assisted living/drug and alcohol rehabilitation project]. I never knew places like this existed, so it was a fantastic stepping-stone. I’m not saying it’s perfect because as I said I’m a recovering alcoholic and cocaine addict living in a dry house, so life is far from idyllic but it’s on the right track. I’ll get my own place next year and also get back to what other people call normal. (Service user 15)

Another service user, referred from a drug support service, spoke of how Hope helped him manage emotions as he stopped using drugs:

Because of my drug use I’d never dealt with certain emotions, love, guilt and all of them and when I stopped using all of these emotions would come to the surface, so by sitting down and talking to ((Hope project worker)) she actually just showed me how to deal with them in a more appropriate way and to recognise it for what it is, and not go and use because I can't deal with the emotion. (Service user 22)

Trauma and abuse

Some staff highlighted how not all service users’ mental distress was alleviated by the resolution of practical problems. As trust grew, several men expressed how they were able to speak through things in the past they hadn’t previously spoken about, including childhood abuse and past traumatic events. These underlying issues such as past abuse or trauma could have significant ongoing effects for service users that Hope services are neither commissioned nor trained appropriately to support. Whilst Hope workers did their best to refer onto other appropriate support, this was dependent on those other services also being available in a timely and accessible way.

Differences with other services

Several service users compared Hope favourably with other services they had received, such as hospital mental health services or GP services. Some service users described traditional healthcare approaches as harder to talk with; a “brick wall” or “there’s no rapport”. Hope was seen as independent, available when needed and with no other agenda other than to help and support:

I think that was the biggest difference I felt from it, which made me more comfortable to work with [Hope] … they couldn’t section me and put me into somewhere…. I saw them as wanting to help, whereas I saw the other ones as almost a threat. (Service user 23)

Hope was commissioned to manage gaps in services, which interviewees had experienced when trying to access other services:

When you’re at your worst you get put on a waiting list for eight to 12 months. (Service user 23)

Diversity of impacts

To summarise, illustrates the range of impacts that service user interviewees spoke about in relation to their support from Hope. Hope was able to tackle and support men through a range of interrelated issues, through their own services and linking with others. The dual aspect of emotional and practical support provided by the Hope service is reflected in the outcomes for service users. shows how all study participants experienced an improvement to their mental health and/or sense of well-being alongside a beneficial change in more practical life issues such as housing, benefits or finance. It was this combination that provided service users with a new sense of self-respect and the ability to begin the process of rebuilding their lives.

Table 4. Impacts of Hope services on different aspects of people’s lives that they spoke of (each row relates to a separate service user interviewed).

Discussion

This study evaluated the acceptability and usefulness of Hope, to understand how the service supports men at risk of suicide. The integration of practical and emotional support provided a holistic service to men, whose suicidal acts or ideation were closely intertwined with life crises. Existing evidence identifies several key elements in suicide prevention that the Hope service has brought together. Hope’s project workers listened to and supported men in non-judgemental and compassionate ways, providing coping and emotional regulation techniques as well as a pragmatic, solutions-focus and motivational approach in an informal, community-based setting, key features identified as important in several studies (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Cole-King et al., Citation2013; Nicholas et al., Citation2020; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). The issue of men feeling a “loss of control” and the importance of regaining control was identified by Wyllie et al. (Citation2012). This was evident in Hope services in the way that men had “control” during their sessions as they set the priorities and preferred ways of meeting. Crucially men also gained control over life crises such as homelessness and debt, that from their perspective had become uncontrollable and unnavigable, working with specialists on issues such as finance or housing and referring to others. There was a perception of less power differentials between Hope project workers and service users in contrast to mainstream health services, where some men had felt threatened or “ostracised”, an important aspect identified in other suicide prevention literature (Chandler, Citation2021; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). These factors helped men feel safe to share difficult experiences, sometimes of previous trauma or abuse, that they had never spoken of before, although accessing specialist support services in these circumstances was challenging. Hope's referral pathways enabled communications and integration between mental health and substance misuse services; such an integrated approach has been highlighted as important in other literature where men may use alcohol and/or drugs as a way of self-medicating (Chandler, Citation2021; Saini et al., Citation2018).

This qualitative study illustrates the complex, intertwining problems that men faced when feeling suicidal and how an intervention can tackle the multiplicity of these issues within community settings, filling an important research gap (Saini et al., Citation2020; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). There appears to be fewer suicide prevention programmes that have combined these aspects of emotional support with specialist advice into one service in the way that Hope has. Whilst evidence of the impact of COVID-19 on suicide rates is still evolving, studies have noted the adverse economic effects and evidence of a rise in community distress (John et al., Citation2021), both of which suggest that Hope is an important ongoing service, especially in the context of rising living costs (Francis-Devine et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

Service users spoke of very few barriers to accessing Hope. However, the people we interviewed were, or had been, fully engaged with Hope. We were unable to recruit people who had disengaged from the service, which may have led to some bias in the sample. This bias could have caused overoptimism of the effects of Hope, but it nevertheless illustrates the full potential of the service. Staff highlighted that disengagement could be due to factors including being too distressed, and/or not being ready to deal with the issues they were facing. Referrers saw instances of disengagement due to repeat offending behaviour to finance continuing addictions. Disengagement may have also been indicative of dissatisfaction.

Interviews had to be done by phone rather than face-to-face due to the COVID-19 pandemic which may have impacted the depth that some service users felt comfortable going into. Our sample of service users from Black, Asian and other ethnic communities was limited.

Implications

The Hope service was commissioned with the support of a central government initiative to tackle suicide (Mental Health Taskforce, Citation2016), and this article, alongside other evidence (Jackson et al., Citation2022; Barnes et al., Citation2018) illustrate the positive results it has achieved. However traditional funding streams tend to focus either on mental health (i.e. NHS psychiatric services), or practical and legal advice (i.e. local authority/Legal Aid) which have been subject to severe cuts (McDermont et al., Citation2017; Newman & Gordon, Citation2019). Whilst there have been developments to integrate services, and Hope is an exemplar of an effective integrated service, there is a strong need to ensure such services are appropriately funded. This study supports existing evidence of the factors that contribute to high suicide rates amongst middle-aged men including difficulties in obtaining appropriate help, isolation, loss, grief, family difficulties, alongside practical problems associated with housing, finances and employment (Chandler, Citation2021; Cleary, Citation2017; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019; Wyllie et al., Citation2012). It highlights the necessity of suicide prevention services to support people through both psychological and broader socioeconomic difficulties, providing further evidence that ways of preventing suicide need to be focussed on people’s social and economic circumstances as well as their health (Chandler, Citation2021; Wyllie et al., Citation2012). Further service development and research is needed to understand whether Hope might have the same impacts for a female population and one which is more ethnically diverse.

Conclusion

The Hope service enables integrated support for men at risk of suicide, tackling structural issues such as homelessness and debt, alongside emotional support. Funding to support cohesive services are key to tackle financial and mental health difficulties, especially given financial and employment uncertainties since the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside rising costs of living.

Author contribution

MTR, JJ, MO and JSp were responsible for study development. JB, MF and MTR formulated the research questions and designed the study. RM supported recruitment of service users to the study. MF and JB collected data. MF, JB and LM analysed the qualitative data. MO, CC, JSm and JSp provided service specific expertise. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Hope project staff, the patient and public involvement members of the study team, and the service users who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

Marina O’Brien and Rebecca Morgan work for Second Step which runs the Hope service. NIHR ARC West received a small grant of £3,000 from Second Step to support evaluation costs.

Data availability statement

Data associated with this manuscript is accessible only to the research team and is not publicly available due to concerns about confidentiality in a study based in a specific locality and with a small sample size.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnes, M. C., Haase, A. M., Bard, A. M., Donovan, J. L., Davies, R., Dursley, S., Potokar, J., Kapur, N., Hawton, K., O’Connor, R. C., Hollingworth, W., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2017). HOPE: Help fOr People with money, employment, benefit or housing problems: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 3(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0179-y

- Barnes, M. C., Haase, A. M., Scott, L. J., Linton, M. J., Bard, A. M., Donovan, J. L., Davies, R., Dursley, S., Williams, S., Elliott, D., Potokar, J., Kapur, N., Hawton, K., O'Connor, R. C., Hollingworth, W., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2018). The help for people with money, employment or housing problems (HOPE) intervention: Pilot randomised trial with mixed methods feasibility research. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4, 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-018-0365-6

- Chandler, A. (2019a). Boys don’t cry? Critical phenomenology, self-harm and suicide. The Sociological Review, 67(6), 1350–1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119854863

- Chandler, A. (2019b). Socioeconomic inequalities of suicide: Sociological and psychological intersections. European Journal of Social Theory, 23(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431018804154

- Chandler, A. (2021). Masculinities and suicide: Unsettling ‘talk’ as a response to suicide in men. Critical Public Health, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.1908959

- Chopra, J., Hanlon, C. A., Boland, J., Harrison, R., Timpson, H., & Saini, P. (2022). A case series study of an innovative community-based brief psychological model for men in suicidal crisis. Journal of Mental Health, 1-10, 31(3), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1979489

- Cleary, A. (2017). Help-seeking patterns and attitudes to treatment amongst men who attempted suicide. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 26(3), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2016.1149800

- Cole-King, A., Green, G., Gask, L., Hines, K., & Platt, S. (2013). Suicide mitigation: A compassionate approach to suicide prevention. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 19(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.110.008763

- Coope, C., Donovan, J., Wilson, C., Barnes, M., Metcalfe, C., Hollingworth, W., Kapur, N., Hawton, K., & Gunnell, D. (2015). Characteristics of people dying by suicide after job loss, financial difficulties and other economic stressors during a period of recession (2010–2011): A review of coroners’ records. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.045

- Francis-Devine, B., Harari, D., Keep, M., & Bolton, P. (2022). Rising cost of living in the UK. UK Parliament.

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Gunasinghe, C., Gazard, B., Aschan, L., MacCrimmon, S., Hotopf, M., & Hatch, S. L. (2018). Debt, common mental disorders and mental health service use. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(6), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1487541

- Gunnell, D., & Chang, S. S. (2016). Economic recession, unemployment, and suicide. In R. C. O'Connor & J. Pirkis (Eds.), The international handbook of suicide prevention (2nd ed., pp. 284–300). John Wiley & Sons.

- Ibrahim, S., Hunt, I. M., Rahman, M. S., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2019). Recession, recovery and suicide in mental health patients in England: Time trend analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(4), 608–614. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.119

- Jackson, J., Farr, M., Birnie, K., Davies, P., Mamluk, L., O'Brien, M., Spencer, J., Morgan, R., Costello, C., Smith, J., Banks, J., & Redaniel, M. T. (2022). Preventing male suicide through a psychosocial intervention that provides psychological support and tackles financial difficulties: a mixed method evaluation. BMC Psychiatry, 22(333), 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03973-5.

- John, A., Eyles, E., Webb, R. T., Okolie, C., Schmidt, L., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., O'Connor, R. C., Kapur, N., Moran, P., O'Neill, S., McGuiness, L. A., Olorisade, B. K., Dekel, D., Macleod-Hall, C., Cheng, H.-Y., Higgins, J. P. T., & Gunnell, D. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: update of living systematic review [version 2; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Research, 9(1097), 1097. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.25522.2

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- McDermont, M., Crawford, B., & Evans, S. (2017). Advising in Austerity: The value of good advice. University of Bristol. Retrieved from https://www.bristol.ac.uk/policybristol/policy-briefings/value-of-advice/

- Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Dennis, M. S. (2011). Personal debt and suicidal ideation. Psychological Medicine, 41(4), 771–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001261

- Mental Health Taskforce (2016). The five year forward view for mental health. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Mental-Health-Taskforce-FYFV-final.pdf

- Newman, D., & Gordon, F. (2019). Legal aid at 70: How decades of cuts have diminished the right to legal equality. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/legal-aid-at-70-how-decades-of-cuts-have-diminished-the-right-to-legal-equality-120905

- Nicholas, A., Pirkis, J., & Reavley, N. (2020). What responses do people at risk of suicide find most helpful and unhelpful from professionals and non-professionals? Journal of Mental Health, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1818701

- ONS (2019). Suicides in the UK: 2018 registrations. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS (2021). Suicides in England and Wales: 2020 registrations. Office for National Statistics.

- Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2013). The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1148–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.009

- Saini, P., Chantler, K., & Kapur, N. (2018). GPs’ views and perspectives on patient non-adherence to treatment in primary care prior to suicide. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294736

- Saini, P., Kullu, C., Mullin, E., Boland, J., & Taylor, P. (2020). Rapid access to brief psychological treatments for self-harm and suicidal crisis. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 70(695), 274–275. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X709913

- Struszczyk, S., Galdas, P. M., & Tiffin, P. A. (2019). Men and suicide prevention: a scoping review. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 28(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370638

- WHO (2014). Preventing suicide: a global imperative. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/131056

- Wykes, T., Bell, A., Carr, S., Coldham, T., Gilbody, S., Hotopf, M., Johnson, S., Kabir, T., Pinfold, V., Sweeney, A., Jones, P. B., & Creswell, C. (2021). Shared goals for mental health research: what, why and when for the 2020s. Journal of Mental Health, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1898552

- Wyllie, C., Platt, S., Brownlie, J., Chandler, A., Connolly, S., Evans, R., Kennelly, B., Kirtley, O., Moore, G., O'Connor, R., & Scourfield, J. (2012). Men, suicide and society: Why disadvantaged men in mid-life die by suicide. Samaritans.

Appendix A

Interview topic guides

HOPE Service User Topic Guide Questions

We would like to get some background information on who we’re speaking with, if you’re happy to provide us with these details.

Could you share with us your age range e.g. forties, fifties.

How would you describe your ethnic background?

When did you last have a session with the Hope service?

Do you remember how many sessions you had with a Hope worker?

Did you always see the same person at HOPE sessions or did you see different people?

Did you have the sessions face to face or over the phone? What was that like? What was the difference like between them?

If you had face to face sessions where did you meet?

What was it like talking to the Hope worker?

Did you feel able to say everything that you wanted to?

Can you talk me through what happens in a Hope session?

Did you get what you needed out of the sessions?

Could you tell me how the relationship with the Hope worker has developed over time / sessions?

Did you have any other form of contact other than sessions? i.e. phone conversations or texts messages?

Were these helpful in between sessions? How?

Can you tell me briefly about your situation that led you to come to the Hope service?

How did you make the connection with HOPE?

Did you get enough sessions and long enough sessions with Hope?

How did Hope help you manage the issues that you were facing? How have these issues changed since accessing the Hope service?

(Extra prompt if needed?) How has the Hope service made a difference to you?

Did you get referred to other organisations by the Hope service? Did you go to those organisations and did they help?

How does the Hope service compare to other forms of support you have accessed?

What’s been the impact of the HOPE sessions for you/on your life?

How is your general financial stability/employment situation now?

COVID-19

(10) Have you had any Hope sessions since the coronavirus lockdown? (If yes, ask a and b)

Has the HOPE service been able to support you during the lockdown? How has this worked out for you?

Has the form of support been different during the pandemic (e.g. online or telephone rather than face to face)? What was that like?

(11)Is there anything else that the HOPE service could do to support you either during the coronavirus lockdown or more generally, if they were able to?

(12) Would you have any other suggestions on how the HOPE service could be improved?

(13)Is there anything else that you would like to add?

(14) Do you have any comments or feedback on the questions we have asked in this interview?

HOPE and Money Advice Staff Topic Guide Questions

Could you give me some details about your role (make sure they cover: job title, length of time working in service, background experience, location, contact with service users)

Can you tell me a bit about the HOPE service and what it offers people?

Where are all the places that you get referrals from?

Where do most referrals come from?

Do Second Step have any exclusion criteria for referral e.g. current drug addiction issues

What kind of situations do you find people are in when you first meet with them?

How do you prioritise the issues that need to be dealt with? PROMPTS:

Financial situation

Home situation

Employment

Benefits or tax credits

Emotional well-being and health

Addiction e.g. gambling, alcohol, drugs

What do you do in the HOPE sessions?

How many sessions do you give clients? How do you make that decision? When do you refer people to a HOPE money advice worker? (OR if speaking to a HOPE money advice worker: when do people get referred to you?)

Do you find that there is an optimum number of sessions?

How do you use call and text messages? How much contact do you find is needed outside sessions? Do you find this is important in crisis situations?

Do HOPE workers and Money Advice workers work together when supporting the same client? If so, how? (Prompt: explore relationship between the two aspects of the service

How do you deal with situations where the issues presented may take months to resolve e.g. appeals about benefit sanctions, errors on medical assessments for Employment Support Allowance (ESA) and Personal Independence Payments (PIPs)?

Why and when do you refer people to other services?

Have you had to work with clients when they are in an acute crisis (this could be emotional or financial)? What did you do, and what support did you have? What happened with the client?

What changes have you seen in clients through the sessions?

Where are the places where you have seen clients not be able to move forward? Why is that? What do you see would help in these situations?

Do you see any patterns or have any thoughts about why people might not use the full number of sessions that they are entitled to?

Can you tell us the impact of COVID-19/corona virus on the service you provide

Tell us about how it has changed the mode of advice (face to face vs telephone)

Have you seen an impact on the financial situation of the clients you support

Have you seen an impact on the mental health of the clients that you support

Has there been an impact on the range of services that you can refer clients to

Are there more services that you think could or should be providing during the COVID-19 pandemic

Is there anything else that you think the HOPE service should be providing, but is currently unable to?

How often do clients finish their sessions but the issues that they brought remain unresolved?

Do you get enough support and supervision for the work that you do?

What training did you receive?

Is there anything else that you need to provide the service?

Would you have any suggestions on how Second Step could improve its HOPE service?

Is there anything else that you would like to add?

HOPE Service Referral Staff Topic Guide Questions

Could you give me some details about your role (make sure they cover: job title, length of time working in service, location, contact with service users)

Could you tell me how you work with the HOPE service? Could you talk me through how the process of referral works? (prompts below as needed)

What are the factors that make you decide to refer someone to the HOPE service?

Are there specific referral criteria?

How do you assess people to make a referral?

How do you refer people to the Second Step HOPE service?

Do you have any problems making a referral to the HOPE service?

Are there any exclusion criteria that Second Step have in their referral process e.g. current drug problems?

Can you tell us the impact of COVID-19/corona virus on the referral service you provide and the needs that people have when you refer them?

Have you seen an impact on the financial situation of the clients you refer on?

Have you seen an impact on the mental health of the clients that you speak with?

Has there been an impact on the range of services that you can refer clients to?

Are there more services that you think could or should be providing during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Can you say what the HOPE service offers to you as a referral service?

Where would you refer people to if the HOPE service no longer existed?

Where did you refer the HOPE client group to before the HOPE services existed? Were there any issues/ problems with this?

Are there any similar services to the HOPE service? If so, how are they similar/ what are the differences?

Do you know of cases where you have referred people to the service, but then they have not actually accessed the services?

Is there any “safety net” to make sure that people are not in crisis if this happens?

Do you think there are any other barriers to accessing the Hope service?

Have you had any situations where people who have been referred previously to HOPE have come back into your referral service in need (e.g. “revolving door clients”)?

Do you get feedback from people who use the HOPE services after they have been referred?

Do you have any suggestions for how:

The referral process to the HOPE service could be improved?

The Hope service itself could be improved

Is there anything else that you would like to add before we finish?