Abstract

Background

Debates exist regarding the validity and utility of functional psychiatric diagnoses. How mental health diagnoses are understood has real impacts for service users and service delivery.

Aims

To investigate different attitudes about the utility of psychiatric diagnoses.

Methods

Forty-one stakeholders sorted 57 statements related to the usefulness of psychiatric diagnoses. Using q-methodology, four viewpoints were identified and interpreted.

Results

Viewpoint 1 (Pathologising human experience) regarded diagnoses as pseudo-scientific constructs that lacked validity and obscured the relationships between lived experience and distress. Viewpoint 2 (Illnesses like any other) held that labels reflected real disorders and diagnosis offered important benefits for service users and services. Viewpoint 3 (Stigmatised conditions) similarly regarded diagnoses as reflecting real disorders, but diagnostic criteria were viewed as biased and the impacts of applying labels seen as causing problems for service users. Conversely, Viewpoint 4 (Useful short-hands) viewed diagnostic processes as imperfect but necessary for supporting communication and structuring service delivery.

Conclusions

While not all viewpoints are in keeping with empirical evidence, we hope results will enable professionals and service users to take meta-positions in relation to their own and others’ attitudes, and to reflect on the impacts of privileging certain viewpoints over others.

Introduction

The medical model of mental health regards manifestations of distress as ‘symptoms’ of ‘mental disorders’ (Johnstone et al., Citation2018), however, there continues to be an absence of biomarkers for any of the functional psychiatric diagnoses (Moncrieff et al., Citation2022). Instead, revisions of checklists such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (World Health Organization, Citation2019) have been made based on consensus seeking and value judgements regarding what should be considered as ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving (e.g. Davies, Citation2013; Kutchins & Kirk, Citation2001). Revisions of these manuals have resulted in expanding diagnostic criteria, narrowing ways of being that are regarded as ‘normal’ (Johnstone, Citation2022; Timimi, Citation2020). The lack of evidence for the medical model has been the subject of decades of critique by service users (Campbell et al., Citation2013; Griffiths, Citation2019), psychologists (Cooke & Kinderman, Citation2018; Johnstone, Citation2022), psychiatrists (Moncrieff, Citation2014; Timimi, Citation2014), and professionals from other backgrounds (Barker, Citation2011; Watson, Citation2019).

Alongside criticisms regarding the validity of diagnoses, debates have centered on the utility and effects of the labels. Proponents of the medical model have argued the labels offer a shared language which supports communication, guide interventions, remove blame, and validate the severity of a person’s distress (Pitt et al., Citation2009; Reed et al., Citation2011). Others maintain that diagnoses offer little benefit for guiding interventions or shaping services because professionals are poor at agreeing who meets specific diagnostic criteria (Read, Citation2013), and because there remains an absence of evidence indicating that diagnoses enhance outcomes or understandings about a person’s distress (Timimi, Citation2014, Citation2020). Diagnostic labels have been criticised for offering little meaningful detail about an individual’s difficulties (Kinderman et al., Citation2013), for minimising the impact of adversity, oppression, and discrimination (Boyle, Citation2002; Fernando, Citation2017; Kinderman, Citation2019), and for imposing medicalised framings of distress that leave little room for individual or alternative cultural understandings (‘epistemic injustice’, e.g. Ball et al., Citation2023; Kinouani, Citation2019). Certain diagnoses have been linked to stigma and exclusion from services (Lester et al., Citation2020), and some have argued that the perceived benefits of diagnoses may reflect an individual experiencing validation of their suffering, rather than as a direct effect of diagnosis (Kinderman et al., Citation2013).

Critiques of the medical model have gained traction in the last twenty years, with bodies such as the British Psychological Society’s Division of Clinical Psychology (DCP, Citation2013), the United Nations (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2017) and the World Health Organization (Citation2021) releasing statements advocating for the conceptualisation of human suffering within the context of lived experience, oppression, and power imbalances. Despite this, the medical model continues to occupy a dominant position within the Global North, with implications for the organisation of health services, the criminal justice system, and access to welfare support (Szmukler, Citation2014). The perseverance of the medical model has been linked to the vested interests of drug companies and professionals invested in diagnostic systems (Harper, Citation2013; Pilgrim, Citation2015). Those who challenge the medical model risk being dismissed for trivialising people’s suffering, blaming the person for their distress, or being complicit with professional ‘power grabs’ (Johnstone, Citation2022).

Within this context, online debates about the utility of diagnoses and alternative approaches can become heated, with interactions between those who hold differing perspectives sometimes descending into personal attacks (Johnstone et al., Citation2019). While such practice from professionals is clearly unacceptable, the intensity of the debates may reflect a tendency to conflate arguments about the utility of psychiatric diagnoses with arguments about validity (Kendell & Jablensky, Citation2003). This can result in the illusion of ‘for’ or ‘against’ diagnosis positions, which fail to account for nuance and appear unconducive to change. Clinicians who recognise the problems with functional psychiatric diagnoses experience challenges exploring different understandings of distress with colleagues and service users because of the dominance of the medical model and the dismissal of critiques (Cooke et al., Citation2019). Research has also observed that professionals conceptualise certain diagnoses in different ways in general discussions compared to in conversations about specific clinical situations (de Waal et al., Citation2022).

In the absence of a systematic study into differing attitudes towards the utility of mental health diagnoses, this research was undertaken with the aim of delineating nuanced viewpoints that encompass views about the validity and utility of mental health diagnoses. It was hoped that presenting differing viewpoints may aid service users and professionals to reflect on their own and others’ viewpoints and the implications of these positions.

Materials and Methods

Design

Q-methodology supports investigation into the subjectivity of people’s views (McKeown & Thomas, Citation2013) and prompts individuals to consider their viewpoint about different facets of a topic in relation to one another (Webler et al., Citation2007). This differs to methodological techniques such as Likert scales, where items are considered in isolation and differences in interpretation of items between participants is regarded as error (Ho, Citation2017; Webler et al., Citation2007). Q-methodology aligns with a qualitative research paradigm which also uses statistical analysis to support the delineation of different viewpoints on a particular topic (Brown, Citation1993).

Participants

Sample sizes of 30 to 50 are typically regarded as acceptable in q-methodology (McKeown & Thomas, Citation2013) and recommendations suggest recruiting fewer participants than statements in the q-set (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). Individuals could participate if they were aged over 18 years and had either worked within or accessed mental health services. Academics with an interest in mental health could also participate. Participants were also recruited through advertisements within non-statutory services, online mental health forums/groups, and university courses. Q-methodology privileges purposive sampling to maximise the diversity of viewpoints represented (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). Thus, early opportunistic recruitment gave way to a purposive strategy that was guided by: (a) ongoing data analysis to identify underrepresented or absent viewpoints; and (b) monitoring diversity of participants in terms of people who had used or worked in mental health services, including diversity in mental-health professional background and other demographic data. People expressing an interest in taking part responded to a Likert-scale question concerned with their beliefs about the use of mental health diagnoses. After several people who were critical of diagnosis had been recruited, this question was used to ensure that people with different perspectives were invited to take part.

Materials

The q-set is a collection of statements that depict the various outlooks related to a subject (Brown, Citation1993). The q-set was generated by gathering naturalistic statements about the perceived utility of mental health diagnoses from focus groups with 17 people (mental health professionals and service users) and a review of existing written material on public-facing social media, academic articles, blogs, and newspaper articles. A set of statements was generated and refined through discarding statements with similar semantic meanings and seeking balance between the quantity of statements relating to differing themes (Coogan & Herrington, Citation2011). Theme labels were developed inductively by coding statements at the semantic level (e.g. stigma; identity) (McKeown & Thomas, Citation2013).

Pilot participants who met the inclusion criteria (n = 9) took part in individual interviews where they considered how readily they could sort the statements into ‘disagree’, ‘neutral’ and ‘agree’ piles. Relative balance between the agree and disagree piles was considered during piloting. Pilot participants also provided feedback on the accessibility of individual items, and whether there were any statements they believed should be added. Piloting resulted in a net reduction from 64 to 57 statements and continued until trivial changes to the q-set were being suggested.

Procedure

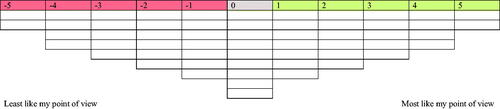

Ethical approval was granted by The University of Leicester School of Psychology Research Ethics Committee (28016-efh6-ls:neuroscience,psychology&behaviour). Informed consent was sought ahead of q-sort interviews, which were undertaken remotely using teleconferencing platforms and Easy HtmlQ (Banasick, Citation2021a); software that enables participants to complete the q-sort task online. In most cases (n = 33), participants shared their screen with the researcher during the q-sorting task. When participants were not able or willing to share their screen, the interviewer remained present on the call for all but two participants who completed the task independently and were interviewed afterwards. When present on the call, qualitative data provided by participants during the task was recorded or noted with participants consent. The q-sort task involved participants organising the 57 statements onto a grid with a quasi-normal distribution () to indicate which statements were least (-5) to most (+5) like their point of view with regards to the utility of mental health diagnoses. Once participants were satisfied with their sorts, they completed a semi-structured interview to gather more in-depth information about their viewpoint. The interview schedule included questions about the statements participants most strongly dis/agreed with, the statements participants found hardest to sort, whether they had approached the sorting-task in a particular way, whether they had any views they wanted to expand upon or that were not captured by the statements, and questions about specific statements (e.g. which labels they thought were more stigmatized and why, if they had agreed with statement 21).

Analysis

The q-sort data was analysed using Ken-Q Analysis Desktop Edition (Banasick, Citation2021b). Correlations between participants’ q-sort compositions were calculated and an inverted factor analysis using the centroid method was performed. Four factors were first subjected to varimax rotation and then judgmental rotation to ensure at least two participants loaded onto the weaker factors (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012; see supplementary material for more information on factor extraction). A composite factor array was generated for each factor, showing how participants would have sorted the statements if they had loaded perfectly onto a particular factor. Exemplar participants, those whose sorts significantly (p < .01) and exclusively loaded onto one factor, were used to constitute the factor arrays. Interpretation of the arrays was supported first through reference back to exemplar participants’ qualitative data, and then to interview data provided by other participants significantly loading onto that factor (Watts & Stenner, Citation2005). Analysis was aided by the creation of crib sheets that indicated which statements were most strongly dis/agreed with and statements that were rated higher or lower on a given factor compared to the others. This included distinguishing statements, which are statements that were rated significantly (p < .05) higher or lower on a given factor compared to the other factors (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012).

Results

Forty-one participants took part in the study. shows each participant’s factor loadings and how they met study inclusion criteria. Factors will henceforth be referred to as ‘viewpoints’. Nine participants loaded exclusively onto Viewpoint 1 (used services: n = 4, worked in services: n = 7), eight onto Viewpoint 2 (used services: n = 5, worked in services: n = 5), two onto Viewpoint 3 (used services: n = 2, worked in services: n = 1), and four onto Viewpoint 4 (used services: n = 2, worked in services: n = 3).

Table 1. Participant Factor Loadings (2.dp) and Relationship to Mental Health.

Narrative summaries of the viewpoints are presented below, with statement numbers and their rankings presented in brackets (rankings in bold indicate distinguishing statements). Statement rankings and distinguishing statements for each viewpoint are also represented in . Expanded descriptions of the viewpoints that include participant quotes are presented in the supplementary material.

Table 2. Statement Rankings for the Idealised Q-sorts across Viewpoints. Distinguishing Statements for a Viewpoint are Shown in Bold.

Viewpoint 1: Pathologising Human Experience

Mental health diagnoses do not reflect valid or reliable constructs (2:-3; 9:-4; 20:+3; 31:-5; 46:-5; 52:+4; 54:+2). The relevance of adversity and oppression is obscured through medical model framings of distress (3:-4; 44:-4; 53:+4). Therefore, understandable human responses become pathologised and regarded as ‘symptoms’ of pseudo-scientific ‘mental disorders’ (13:-4; 32:+5). Because mental health diagnoses lack evidence of reliability and validity and obscure explorations of the causes and meaning of suffering, the labels fail to offer information that will be useful in improving understandings of distress (38:0; 40:-2; 43:+4; 48:+2; 56:-1), or guiding interventions (19:-3; 35:-1; 36:-2; 49:-1). Although psychiatric diagnoses offer more benefits to services than service users (18:+3), they offer little utility for research, service delivery, or supporting professionals to deliver effective interventions (37:-2; 45:-2; 47:-1). Instead, the dominance of medicalised understandings can be understood as supporting the interests of the pharmaceutical industry (41:+5).

Diagnoses are powerful and harmful when imposed (7:-3; 42:+2). When feelings thoughts and behaviours are framed as ‘symptoms’ of a presumed illness, a person’s experiences come to be made sense of through the lens of a disordered identity (5:+3; 15:+1; 26:+2), in turn negatively impacting upon hope for change (28:-2) and people’s ability to manage their distress (27:-1). This imposed narrative can have negative and stigmatising consequences for an individual in relation to the way they may be responded to or treated by others (8:+4; 39:+3). Although the labels do provide some access to support within work and education settings (4:+2), this is because services and legal systems tend to be built around an unquestioning acceptance of the medical model, and such support could be better provided without reliance on a pathologising and unscientific classification system.

Viewpoint 2: Illnesses Like Any Other

Mental health diagnoses reflect real disorders, with biopsychosocial causation (31:+1; 53:-3), which are just as valid as diagnoses in physical heath (2:0; 3:+4; 46:+2; 52:-4). Because diagnoses rely on detection of real symptoms, their use does not pathologise normal human experience (8:-2; 32:-2) nor do factors such as upbringing, culture, race, and gender impact on whether a person has symptoms or not (1:-5; 10:-1; 20:-1; 44:-2).

Access to mental health services (55:-4) and other forms of support (4:+4; 14:-4) is enabled by diagnosis. Identification of specific mental disorders supports collaboration between professional and service user (45:+2) and enables access to the most effective treatments for a given condition (19:+3; 36:+3; 47:+4). The categories are also important for research and service development (16:+2; 37:+3; 47:+4). Diagnoses provide other benefits for service users (18:-3; 42:-5). These include normalisation and validation of distress (11:-4; 12:+3) and greater understanding of distress by loved ones (38:-3) and the person themselves (6:+5; 26:+2; 29:+5). These benefits, coupled with access to appropriate interventions, positively impacts a person’s hope for change and ability to manage their condition (27:+2; 28:+3). Although there are few negative effects relating to diagnosis, the identification of mental illness can bring problems of stigma due to misunderstandings and prejudice within the general population (21:+4).

Viewpoint 3: Stigmatised Conditions

Psychiatric diagnoses are as valid as diagnosis in the rest of medicine (46:+4; 52:-4) and there is evidence of biological causality (31:+2; 32:-2). However, diagnostic criteria need refinement as current diagnostic practices fail to account for the ways that adversity and oppression relate to distress (2:-3; 9:-4; 24:+4; 44:-4; 53:+3), and criteria contain cultural and gender biases (10:+2; 20:+4; 54:+3). The labels thus have low utility in supporting understandings of why a person is presenting as they are (12:-2; 29:-3; 48:+3). Although they can provide hope for recovery (28:+2), diagnoses offer little useful information about prognosis (35:-4), when someone should be discharged (49:-5), or what a person can do to manage their distress (27:-5).

Once someone has been diagnosed, there is a risk that other aspects of a person’s behaviour become misinterpreted as symptoms of mental illness (5:+1; 15:+3; 26:+2; 39:+2). The imposition of labels acts as a barrier to exploring a person’s own meaning-making of their distress (48:+3). When someone is labelled as having a mental illness, they are likely to encounter stigma, discrimination, and exclusion from society and peers (7:-2; 12:-2; 42:+2; 51:+5), although diagnosis is less likely to impact on support from loved ones (38:-3). Stigma has an impact on how people are treated within services too, with diagnoses enabling harmful practices and presenting barriers to professionals empathising and collaborating with their patients (25:-2; 40:-2; 45:-3). Stigma is heightened for some diagnoses (21:+5) and among some communities (33:+4), indicating more problems with the use of diagnoses for people from non-western cultures (10:+2).

Viewpoint 4: Useful Short-Hands

Diagnostic criteria contain cultural biases (10:+3; 20:+4; 24:+2; 52:+1; 54:+5) and have a problematic evidence base, offering little in the way of explaining why someone is presenting as they are (43:+3; 44:-2; 50:-4; 57:-3). However, issues relating to the validity of psychiatric diagnosis are of low importance (9:-1; 31:-1; 35:-1; 46:0; 50:-4; 52:+1), as diagnoses serve as useful short-hands for communicating information and understanding about a person’s presentation (6:+2; 12:+3; 29:+1; 34:+5; 38:-3; 43:+3). Even though professionals often disagree about who meets diagnostic criteria for a given label (2:-3), diagnoses provide a needed categorisation system for structuring, delivering, and developing mental health services (16:+3; 19:+3; 34:+5; 36:+1; 37:+4; 43:+3; 47:+2; 55:-4). This means that diagnoses can act as gatekeepers to services for individuals attempting to access support (55:-4). Diagnoses do not enhance the working relationship between clinicians and service users (40:-4; 45:-2), and the working relationship remains more important than getting the ‘correct’ diagnosis (30:-5).

Although labels support connection between people with similar presentations (23:+4), other impacts of diagnosis for service users are equivocal (4:+1; 5:-2; 7:-1; 8:0; 15:0; 17:+1; 18:-1; 27:+1; 39:0; 51:0), and likely to vary dependent on an individual, their circumstances, and the relative stigma of a particular diagnosis (21:+4). Although the labels serve to remove blame from relatives (1:-4) and can sometimes remove blame from the diagnosed person, the diagnosis still implies the problem is within the diagnosed person (22:-2). However, use of diagnoses should not be regarded as harmful for those in receipt of them (42:-5).

Discussion

This study was undertaken to address a gap in the systematic exploration of attitudes towards the utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Although impossible to represent all viewpoints, four factors were extracted from the analysis that we hope will support stakeholders to reflect on their own, and others’, positions. Similarities and differences between viewpoints will be considered in relation to extant literature, then study limitations, author positionality, and clinical implications are presented.

Attitudes Towards the Utility of Psychiatric Diagnoses

As post-structural theorists have argued (e.g. Warner, Citation2009) it is problematic to take a relativist position and treat all viewpoints as equal because different positions have real impacts, with dominant positions tending to serve existing societal power-imbalances (Wigginton & Lafrance, Citation2019). Furthermore, while most perspectives are understandable in relation to dominant discourses about ‘mental health’ (Cooke et al., Citation2019), the viewpoints described in this study differ in the extent to which they are supported by empirical evidence. For example, it is understandable that two of the viewpoints (2 and 3) regarded mental health diagnoses as reflecting real biological disorders given the dominance of medical discourses within neoliberal societies (Timimi, Citation2020). However, this is not supported by research (Cromby et al., Citation2013; Moncrieff et al., Citation2022).

Viewpoints 2 and 3 could be described as aligning with the biopsychosocial or stress-diathesis approaches to ‘mental illness’, whereby adversity is seen as triggering biological vulnerability for a given disorder (Pilgrim, Citation2015). These theories have been critiqued for bolstering unsubstantiated medical model understandings whilst minimising or neglecting the role of social context (Boyle, Citation2013; Harper et al., Citation2021). However, the two viewpoints differ as to whether this obscuring of context is problematised or indeed recognised. Viewpoint 3 regards the diagnostic criteria as subjective and culture bound, with use of the labels resulting in harmful stigmatisation that negatively impacts upon how others respond. Conversely, Viewpoint 2 seems most closely aligned with the medical model, regarding diagnoses as scientific classifications essential for determining what ‘disorder’ a person is experiencing. These disorders were seen as existing independently to a person’s experiences and cultural background. This belief also contradicts a large body of evidence linking experiences of adversity and discrimination with greater numbers of psychiatric diagnoses (Johnstone et al., Citation2018). Both viewpoints link with the notion of epistemic injustice, whereby individual and cultural meaning making of suffering is dismissed through imposition of medicalised understandings of distress (Ball et al., Citation2023; Dillon, Citation2019). Clinicians adopting Viewpoint 2 may be less likely to explore the dis/advantages of a diagnosis if they understand their role as detecting the presence of specific ‘mental illnesses’. Nor would they be likely to discuss the limited evidence base for drugs (Moncrieff, Citation2020) or diagnosis-specific talking therapies (Timimi, Citation2020) if they presume that problems are caused by ‘chemical imbalances’ or ‘faulty thinking styles’.

Like Viewpoint 3, the Viewpoint 1 position regarded diagnoses as having potentially harmful impacts with regards to the ways a person and their distress come to be understood. However, this viewpoint was more aligned with the problems of reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses. This viewpoint perceived the dominance of the medical model as linked to the vested interests of institutions and professions who benefit from reframing social issues as individual ‘illnesses’ (Boyle, Citation2013; Harper, Citation2013).

It seemed that the key differences between Viewpoints 1 and 2 related to whether diagnoses reflect valid constructs, however, Viewpoints 3 and 4 placed less emphasis on empirical evidence. Indeed, from the Viewpoint 4 position, diagnostic labels were seen as necessary for supporting communication and structuring services, despite acknowledgement that professionals are poor at agreeing who fits a given label, and that diagnoses are shaped by cultural and gendered assumptions. The view that diagnoses can support the most effective interventions (a position also endorsed within Viewpoint 2) is not well supported by evidence as the use of labels have been implicated with poorer outcomes (Honos-Webb & Leitner, Citation2001; Sayal et al., Citation2010; Timimi, Citation2020); particularly when a biological explanation is given for a person’s distress (Kemp et al., Citation2014; Schroder et al., Citation2020).

Viewpoint 4 also advances the pre-existing narrative that diagnoses, while imperfect, provide the best available means for classifying distress (Johnstone, Citation2022). This directly contrasts with Viewpoint 1 which suggests that the labels have little-to-no utility in shaping services or guiding interventions and calls for alternative approaches that attend to personal and social contexts (e.g. the Power Threat Meaning Framework, Johnstone et al., Citation2018).

All viewpoints except Viewpoint 2 recognised that diagnostic criteria contained racial and cultural biases, although Viewpoint 4 did not regard this as a significant problem in the context of the perceived benefits afforded by use of diagnoses. All viewpoints concurred that mental health diagnoses result in stigma, with some being more stigmatising than others. However, implications for how to tackle stigma may vary with the viewpoints. For example, when stigma is seen as reflecting societal prejudices and misunderstandings about mental illness (Viewpoint 2), then anti-stigma campaigns that aim to educate others about mental disorders (e.g. Stuart, Citation2016) may be employed. In contrast, Viewpoint 1 considered stigma to arise from the assignation of a ‘disordered’ identity. This fits with evidence that suggests that anti-stigma campaigns geared to supporting understanding of ‘mental illness’ might result in increased stigma (Read et al., Citation2006).

Limitations

The views captured within the four factors will not represent all viewpoints relating to psychiatric diagnoses. Notably, we were not able to recruit anyone who believed that psychiatric diagnoses are exclusively linked to biological factors. Although it seems unlikely that people will endorse a solely biological understanding of distress (Read & Sanders, Citation2010), we anticipate that some stakeholders will view mental health in this way. The antagonistic landscape of the dialogue between individuals who hold different views about mental health diagnoses (e.g. Johnstone et al., Citation2019) may have prevented people with certain views from wishing to participate or have impacted on participants expressing their views openly.

Reflexivity

We recognise our own positioning in relation to the research topic and as individuals who met the inclusion criteria, we both participated in the study. Not only is this acceptable in q-methodology, which makes no claims about representativeness of different viewpoints, but researcher participation supports with transparency and reflexivity (e.g. Warner, Citation2009). Both of our sorts loaded onto Viewpoint 1. Our viewpoints will inevitably have shaped our interpretation and framing of results; we engaged in reflective discussions to support our awareness of this. Although we recognise the importance of taking a position in relation to findings (Warner, Citation2009), we have aimed to do so through drawing on links with existing research and have endeavored to remain respectful and understanding to viewpoints that differ from our own.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Four viewpoints regarding the utility of mental health diagnoses were delineated. These viewpoints differed in the degree to which they fitted with empirical evidence, and the degree to which evidence was valued. The viewpoint that diagnoses should be used despite an absence of evidence (Viewpoint 4) supports suggestions that the persistence of the medical model relates to operations of power and ideology rather than a commitment to scientific rigor (Johnstone, Citation2022; Pilgrim, Citation2015). Nevertheless, evidence was important for Viewpoints 1 and 2, indicating that many people who adhere to the biopsychosocial model of ‘mental illness’ understandably do so because of the ways evidence is manipulated and misrepresented (Boyle, Citation2002; Joseph, Citation2004). This highlights the necessity of challenging the medical model within mental health training and teaching (Cromby et al., Citation2008), and the importance of providing information about the lack of evidence for biological causation for people accessing services (Honos-Webb & Leitner, Citation2001). This should not mean that people accessing services have their illness beliefs directly challenged or be coerced into thinking about their distress in ways that do not fit for them, but that different ways of thinking about distress are offered (Johnstone et al., Citation2018). Psychological formulations, provided they are collaborative, can be useful in empowering people to develop non-blaming understandings of their distress that privilege individuals’ own meaning making; ideally also offering ways in which wellbeing may be improved (Johnstone, Citation2018).

Agreement and ‘middle grounds’ should not be seen as desirable in debates about how we make sense of suffering given the real-life impacts of how distress is conceptualized (Dillon, Citation2019). However, we hope that the results of this study can be used to support professionals and service users to recognise that there are different ways of making sense of distress; the importance of which has also been highlighted by de Waal et al. (Citation2022) in relation to ‘schizophrenia’ diagnoses. The four viewpoints identified are abstracted and are not mutually exclusive. People will likely align with some aspects of multiple viewpoints and disagree with other aspects. We hope the results will aid people to take meta-positions (Andersen, Citation1987) with regards to their own and others’ perspectives in ways that can support collaborative dialogue (Campbell & Groenbeck, Citation2006) and a paradigm shift towards non-pathologising understandings of distress. It is important to note that participants loading onto all four viewpoints spoke about people diagnosed with mental health labels with great respect, and all wanted effective, humane, and non-blaming mental health services.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (185.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

A dataset of individual ranking of statements can be shared with researchers for reanalysis provided the researchers have obtained appropriate ethical approval and any reanalysis is deemed to fit with the aims of the original study that participants consented to take part in.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). APA.

- Andersen, T. (1987). The reflecting team: dialogue and meta-dialogue in clinical work. Family Process, 26(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00415.x

- Ball, M., Morgan, G., & Haarmans, M. (2023). The Power Threat Meaning Framework and ‘psychosis'. In J. A. Diaz-Garrido, R. Zuniga, H. Laffite, & E. Morris (Eds.), Psychological interventions for psychosis: Towards a paradigm shift. Springer.

- Banasick, S. (2021a). Easy HtmlQ (Version 2.0.3) [Computer Software]. https://github.com/shawnbanasick/easy-htmlq.

- Banasick, S. (2021b). KenQ Analysis Desktop Edition [Computer Software]. https://github.com/shawnbanasick/kade.

- Barker, P. (2011). Psychiatric diagnosis. In P. Barker (Ed.), Mental health ethics: The human context. Routledge.

- Boyle, M. (2002). Schizophrenia: A Scientific Delusion? (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Boyle, M. (2013). The persistence of medicalisation: Is the presentation of alternatives part of the problem?. In S. Coles, S. Keenan & B. Diamond (Eds.), Madness contested: Power and Practice. PCCS books.

- Brown, S. R. (1993). A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16(3/4), 91–138. https://doi.org/10.22488/okstate.93.100504

- Campbell, D., & Groenbeck, M. (2006). Chapter 3: Putting the model into practice. In D. Campbell, & M. Groenbeck (Eds.), Taking positions in the organization (pp 33–42). Routledge.

- Campbell, P., Longden, E., & Dillon, J. (2013). Service users and survivors. In J. Cromby, D. Harper, & P. Reavey (Eds.), Psychology, mental health and distress. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Coogan, J., & Herrington, N. (2011). Q methodology: An overview. Research in Teacher Education, 1(2), 24–28.

- Cooke, A., & Kinderman, P. (2018). But what about real mental illnesses?” Alternatives to the disease model approach to “schizophrenia. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 58(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817745621

- Cooke, A., Smythe, W., & Anscombe, A. (2019). Conflict, compromise and collusion: dilemmas for psychosocially-oriented practitioners in the mental health system. Psychosis, 11(3), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2019.1582687

- Cromby, J., Harper, D., & Reavey, P. (2008). Mental health teaching to UK psychology undergraduates: report of a survey. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 18(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.913

- Cromby, J., Harper, D., & Reavey, P. (2013). Psychology, mental health & distress. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, J. (2013). Cracked: Why psychiatry is doing more harm than good. Icon Books Ltd.

- de Waal, H., Boyle, M., & Cooke, A. (2022). Trapped in contradictions: professionals’ accounts of the concept of schizophrenia and its use in clinical practice. Psychosis, https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2022.2086607

- Dillon, J. (2019). Names matter, language matters, truth matters. In J. Watson (Ed.), Drop the disorder. Challenging the culture of psychiatric diagnosis. PCSS.

- Division of Clinical Psychology. (2013). Classification of behaviour and experience in relation to functional psychiatric diagnoses: Time for a paradigm shift. British Psychological Society.

- Fernando, S. (2017). Institutional racism in psychiatry and clinical psychology: Race matters in mental health. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Griffiths, A. (2019). Reflections on using the Power Threat Meaning Framework in peer led systems. Clinical Psychology Forum, 1(313), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpf.2019.1.313.9

- Harper, D. J. (2013). On the persistence of psychiatric diagnosis: Moving beyond a zombie classification system. Feminism & Psychology, 23(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353512467970

- Harper, D. J., O’Donnell, E., & Platts, S. (2021). A “trigger”, a cause or obscured? How trauma and adversity are constructed in psychiatric stress-vulnerability accounts of “psychosis. Feminism & Psychology, 31(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520954313

- Ho, G. W. (2017). Examining perceptions and attitudes: A review of Likert-type scales versus Q-methodology. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 39(5), 674–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916661302

- Honos-Webb, L., & Leitner, L. M. (2001). How using the DSM causes damage: A client’s report. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41(4), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167801414003

- Johnstone, L. (2018). Psychological Formulation as an Alternative to Psychiatric Diagnosis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 58(1), 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817722230

- Johnstone, L. (2022). A straight talking introduction to psychiatric diagnosis. (2nd ed.) PCCS Books.

- Johnstone, L., Boyle, M., Cromby, J., Dillon, J., Harper, D., Kinderman, P., Longden, E., Pilgrim., & D., Read. (2018). The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis. British Psychological Society.

- Johnstone, L., Boyle, M., Cromby, J., Dillon, J., Harper, D., Kinderman, P., Longden, E., Pilgrim, D., & Read, J. (2019). Reflections on responses to the Power Threat Meaning Framework one year on. Clinical Psychology Forum, 1(313), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpf.2019.1.313.47

- Joseph, J. (2004). The gene illusion: Genetic research in psychiatry and psychology under the microscope. PCCS Books.

- Kemp, J., Lickel, J., & Deacon, B. (2014). Effects of a chemical imbalance causal explanation on individuals’ perceptions of their depressive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.009

- Kendell, R., & Jablensky, A. (2003). Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4

- Kinderman, P. (2019). A manifesto for mental health: Why we need a revolution in mental health care. Springer Nature.

- Kinderman, P., Read, J., Moncrieff, J., & Bentall, R. P. (2013). Drop the language of disorder. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 16(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2012-100987

- Kinouani, G. (2019). Violence under the guise of care: Whiteness, colonialism and psychiatric diagnosis. In J. Watson (Ed.), Drop the disorder: Challenging the culture of psychiatric disorder. PCCS Books.

- Kutchins, H., & Kirk, S. (2001). Making us crazy. DSM: The psychiatric bible and the creation of mental disorders. Free Press.

- Lester, R., Prescott, L., McCormack, M., & Sampson, M, North West Boroughs Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. (2020). Service users’ experiences of receiving a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Personality and Mental Health, 14(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1478

- McKeown, B., & Thomas, D. B. (2013). Q methodology. (Vol. 66). Sage publications.

- Moncrieff, J. (2014). The nature of mental disorder: Disease, distress, or personal tendency? Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 21(3), 257–260. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2014.0028

- Moncrieff, J. (2020). A straight talking introduction to psychiatric drugs. The truth about how they work and how to come off them. PCCS Books.

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R. E., Stockmann, T., Amendola, S., Hengartner, M. P., & Horowitz, M. A. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2017). Special Rapporteur on the right to physical and mental health. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-health?v=1392752313000/

- Pilgrim, D. (2015). The biopsychosocial model in health research: Its strengths and limitations for critical realists. Journal of Critical Realism, 14(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1179/1572513814Y.0000000007

- Pitt, L., Kilbride, M., Welford, M., Nothard, S., & Morrison, A. P. (2009). Impact of a diagnosis of psychosis: user-led qualitative study. Psychiatric Bulletin, 33(11), 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.108.022863

- Read, J. (2013). Does ‘schizophrenia’ exist? Reliability and validity. In J. Read, R. Bentall, L. Mosher & J. Dillon (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to psychosis (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

- Read, J., & Sanders, P. (2010). A straight talking introduction to the causes of mental health problems. PCCS Books.

- Read, J., Haslam, N., Sayce, L., & Davies, E. (2006). Prejudice and schizophrenia: a review of the ‘mental illness is an illness like any other’ approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(5), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00824.x

- Reed, G. M., Correia, J. M., Esparza, P., Saxena, S., & Maj, M. (2011). The WPA-WHO global survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes towards mental disorders classification. World Psychiatry, 10(2), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00034.x

- Sayal, K., Owen, V., White, K., Merrell, C., Tymms, P., & Taylor, E. (2010). Impact of early school-based screening and intervention programs for ADHD on children’s outcomes and access to services: Follow-up of a school-based trial at age 10 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.40

- Schroder, H. S., Duda, J. M., Christensen, C., Beard, C., & Björgvinsson, T. (2020). Stressors and chemical imbalances: Beliefs about the causes of depression in an acute psychiatric treatment sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.061

- Stuart, H. (2016). Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Global Mental Health, 3, e17. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.11

- Szmukler, G. (2014). When psychiatric diagnosis becomes an overworked tool. Journal of Medical Ethics, 40(8), 517–520. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2013-101761

- Timimi, S. (2014). No more psychiatric labels: Why formal psychiatric diagnostic systems should be abolished. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 14(3), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2014.03.004

- Timimi, S. (2020). Insane medicine: How the mental health industry creates damaging treatment traps and how you can escape them. Amazon.

- Warner, S. (2009). Understanding the effects of child sexual abuse: Feminist revolutions in theory, research and practice. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Watson, J. (2019). There’s an intruder in our house! Counselling, psychotherapy and the biomedical model of emotional distress. In J. Watson (Ed.), Drop the disorder: Challenging the culture of psychiatric disorder. PCCS Books.

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp022oa

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method and Interpretation. Sage.

- Webler, T., Danielson, S., & Tuler, S. (2007). Guidance on the use of Q method for evaluation of public involvement programs at contaminated sites. Social and Environmental Research Institute.

- Wigginton, B., & Lafrance, M. N. (2019). Learning critical feminist research: A brief introduction to feminist epistemologies and methodologies. Feminism & Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353519866058

- World Health Organization. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. (11th ed.) WHO. https://icd.who.int/

- World Health Organization. (2021). Guidance on community mental health services: Promoting person-centred and rights based approaches. WHO. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707