Abstract

Purpose: Supportive interventions to enhance return to work (RTW) in cancer survivors hardly showed positive effects so far. Behavioral determinants might have to be considered in the development of interventions to achieve sustained employability. This study aimed to explore cancer survivors’ perspectives and experiences regarding behavioral determinants of RTW and continuation of work.

Materials and methods: In this qualitative study, semi-structured telephone interviews were held with 28 cancer survivors. All participants were at working age, 1–2 years after diagnosis and employed at time of diagnosis. Thematic content analysis was performed.

Results: Work turned out to be a meaningful aspect of cancer survivors’ life, and most participants reported a positive attitude towards their job. Social support to RTW or to continue working was mainly received from family and friends, but pressure to RTW from the occupational physician was also experienced. Changes in expectations regarding work ability from negative to positive during the treatment process were observed. Those who applied active coping mechanisms felt equipped to deal with difficulties regarding work.

Conclusions: Behavioral determinants should be taken into account in the development of future interventions to support cancer survivors’ RTW. However, the causal relationship still has to be determined.

Factors influencing occupational motivation among cancer survivors need to be understood in more detail.

Previous studies in non-cancer populations have demonstrated that behavioral determinants, such as a positive attitude towards work, high social support and self-efficacy may increase return to work rates or shorten the time to return to work.

Addressing behavioral determinants in future development of work-related interventions for cancer survivors is essential in achieving sustained employability.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

In Europe, about 3.5 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, of whom 50% is part of the working population.[Citation1–3] Survivor rates of people diagnosed with cancer are increasing [Citation4–6] as well as their ability to return to work (RTW), or even continue working while being treated for cancer.[Citation1,Citation7]. One year after diagnosis, about 62% of the cancer survivors have returned to work.[Citation8] Still, they are 1.4 times more likely to be unemployed than healthy persons.[Citation9] RTW can be hindered or even become impossible as a consequence of disease- and treatment-related factors,[Citation8] such as fatigue or pain.[Citation10–13] Also, re-entering the workplace can be negatively affected by sociodemographic (e.g., higher age, being female, lower educational level) and work-related factors (e.g., no adjustments at work).[Citation8]

Over the past decades, different types of interventions focusing on RTW, or corresponding concepts such as sickness absence, have been developed for cancer survivors, primarily aimed at disease-, treatment-, and/or work-related factors.[Citation14,Citation15] For example, in a study by Rogers et al.,[Citation16] the effect of a physical training intervention on the number of days of sickness absence in cancer survivors was compared with care as usual. However, no significant effect of the training intervention on the days missed from work was found. In addition, Tamminga et al. (2013) assessed the effect of a hospital-based work support intervention for cancer patients, focusing on the communication between the treating physician and the patients’ occupational physician, in order to enhance RTW. Again, no statistically significant difference was found between the intervention and the care as usual the control group.[Citation17] Based on these, and several other non-significant intervention studies,[Citation14,Citation15] it can be concluded that additional factors have to be considered in the development of interventions to support RTW and continuation of work in cancer survivors [Citation18].

Previous studies in non-cancer populations have demonstrated that behavioral determinants, such as a positive attitude towards work, high social support and self-efficacy, and optimistic beliefs may increase RTW rates or shorten the time to RTW.[Citation19,Citation20] In order to understand the influences of behavioral determinants on RTW, behavioral theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) or Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), can be considered.[Citation21,Citation22] According to the TPB, health-related behavior can be predicted by the intention to perform this behavior. Moreover, the intention itself can be affected by determinants, e.g., attitude towards the behavior, which can be positive or negative, subjective norm or social support, and perceived behavioral control, also known as self-efficacy.[Citation21] Mehnert et al. (2013) showed that RTW intention appeared to be a strong predictor for RTW (OR 6.22; 95% CI 1.98–19.51). However, they concluded that factors influencing occupational motivation among cancer survivors need to be understood in more detail.[Citation22] According to SCT, based on the learning theory of Bandura,[Citation23] behavior is best predicted by the expectation a person has about a certain behavior. For example, Cornelius et al. [Citation24] indicated that individuals with a mental health disorder, expressing a positive expectation about the ability to RTW, turned out to be more likely to re-enter the workplace compared to those expressing negative expectations. However, when exploring studies on RTW and continuation of work in cancer survivors, there is a lack of information regarding such behavioral determinants.[Citation18,Citation25,Citation26]

To gain more insight in this subject, the aim of this study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of cancer survivors regarding behavioral determinants of RTW and continuation of work. Addressing these determinants in future development of work-related interventions for cancer survivors might be essential in achieving sustained employability.

Materials and methods

Design and procedures

In this qualitative study, semi-structured one-to-one telephone interviews were conducted by a senior researcher (SD). A face-to-face interview was only scheduled if this was more convenient for the participant. Survivors from breast cancer, colorectal cancer, or head and neck cancer were selected through the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek hospital tumor registry. They were invited, by their treating medical specialist, to complete a questionnaire and written informed consent, which were sent to them by postal mail. In November 2014, a first wave of cancer survivors (N = 67), diagnosed between 1 April 2013 and 31 October 2013, was invited. A second wave of potential participants was invited in January 2015 (N = 63). These participants were diagnosed between 1 October 2012 and 31 March 2013. Herewith, all participants were between 1 and 2 years after their diagnosis. Information from the questionnaires was used for the selection of participants for the interviews: they had to be between 18 and 60 years of age, and had to have an employment contract or had to be self-employed at time of diagnosis. In addition, they should have completed active treatment, i.e., chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and they could either be on sick leave or have returned to work at time of questionnaire completion. The Medical Ethical Committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, approved the study. The COREQ criteria were used as a guideline for reporting this qualitative study.[Citation27]

Questionnaire and interview

The questionnaire contained sociodemographic items, i.e., age (in years), gender (male/female), marital status (not married/married/LAT/divorced/widowed/other), and educational level (none/primary school/lower vocational education/secondary or vocational school/upper secondary school/upper vocational education/university), disease- and treatment-related items, i.e., cancer site (breast/colorectal/head and neck), and type of treatment (surgery/radiotherapy/chemotherapy/hormone therapy/immunotherapy/hyperthermia/other). In addition, the questionnaire included work-related items, i.e., employment status (working/not working), type of job at the time of diagnosis (white collar/civil servant/blue collar/health care worker), and work demands (mainly psychological/mainly physical/both psychological and physical).

The interviews were semi-structured by using a topic list that contained nine focus areas. This topic list was largely based on the findings of a recent review exploring a behavioral approach, e.g., the use of models and theories such as the TPB and SCT, in the development of work-related interventions.[Citation18,Citation21,Citation22] The first and the last question of the interview were introductory and closing topics, respectively. Specifically, the participant was asked (1) what factors (s)he considered to affect RTW or, when at work, continuation of work, and what factor (s)he considered most influential; (2) about the meaning of work in his/her life, and a potential change of this meaning after being diagnosed with and treated for cancer; (3) about his/her attitude towards work in general and, when at work, towards the current job; (4) whether (s)he had experienced social support and/or pressure (not) to RTW or, when at work, to continue working; (5) about his/her thoughts on the meaning of work to people in general, to explore ideas about the social norm regarding work; (6) about his/her expectations regarding RTW immediately after diagnosis; (7) whether and how (s)he estimated to be in control of factors affecting RTW; (8) about the coping mechanisms (s)he applied in general and, when at work, about his/her coping style regarding problems at work; (9) whether (s)he (had) participated in any program that supports RTW or continuation of work. Before the start of each interview, some questions were adapted, based on the employment status of the participant at time of the interview (i.e., being on sick leave or at work). The interviews were in Dutch, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics from the participants were derived from the questionnaires. Descriptive statistics were applied to present these characteristics. Thematic content analysis consisting of several phases, as described by Wilkinson,[Citation28] was performed by a first researcher (MG) to analyze the data from the interviews. In order to become familiar with the data and to verify the accuracy of the transcriptions, the audio recorded interviews were listened to and the transcribed interviews were read closely. Elements of the earlier described behavioral theories were used to predetermine the themes to code the first three interviews. This resulted in an initial codebook, which was used to analyze the remaining data. When new codes within themes emerged, these were incorporated in the initial codebook and used for further analysis. All themes and codes were discussed with a second researcher (MvE), who subsequently analyzed all data, also by applying the initial codebook. The interrelationship between the generated themes was discussed by both researchers. After consensus on the interpretation of the themes, codes were merged, renamed, and redefined within and between the themes, if necessary. The ATLAS.ti 5.2 software was used for the data analysis.[Citation29,Citation30]

Results

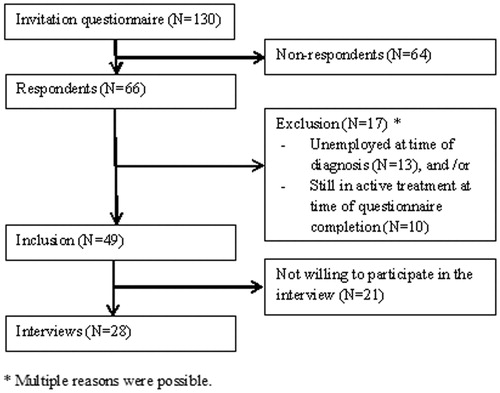

Of the 130 invited cancer survivors, 66 responded to the questionnaire (51%), of whom 49 met the inclusion criteria. Of them, 28 indicated to be willing to participate in an interview. Since after 22 interviews hardly any new information was retrieved, only the six interviews that were already scheduled were completed and no new waves were organized. The average duration of the interview was 32 min (range: 15–45 min). In total, 25 of the interviews were held by telephone; the remaining three interviews were held face-to-face. The reasons for the face-to-face interviews were that one participant had speech problems because of his tracheostoma, and two participants had an appointment in the hospital and preferred the interview being held directly afterwards ().

Participant characteristics

In , an overview of the sociodemographics, disease-, treatment-, and work-related characteristics of the 28 participants is presented. The mean age of the participants was 52 years (range 28–62), 14 participants were male (50%) and fifteen participants had an upper vocational or university level of education (54%). Cancer sites reported by the participants were breast (N = 12), colorectal (N = 5), and head or neck cancer (N = 11). At time of questionnaire completion, 19 participants had returned to work (68%), whereas nine participants were not working (32%).

Table 1. Characteristics of the cancer survivors included in the study.

Interview themes

Meaning of work

Overall, work was a vital aspect of the survivors’ life. They considered working important and many of them pronounced to enjoy their job. For most participants, work had both an intrinsic meaning, e.g., personal development, and an extrinsic meaning, e.g., a contribution to society. For some participants, work predominantly had a financial meaning; for others, work was a distraction of their disease. A few participants thought that the meaning work had in their life influenced their RTW. For example, a 44-year-old man who returned to work stated that working structured his daily life, which he considered an important aspect of working in general. He believed that being able to work and adhering to this structure helped him during his rehabilitation. Another participant, a 50-year-old woman who was occupationally active again, explained: “I think it is better to continue working to have some distraction, to contribute to society and for overall well-being” (P5). A 56-year-old man who had been working for 28 years for the same employer said: “I enjoy my job and I like my colleagues. Work is very important to me” (P20). A woman aged 54 years stressed she did not miss her job while being on sick leave. Recovering from cancer and her treatment was her main priority. However, due to financial reasons she did RTW eventually. For the majority of the participants, work became a less important aspect of their life after being diagnosed with cancer. Some participants explained that, after surviving cancer, they wanted to focus on other aspects of life, e.g., family and friends or their health, instead of their work. A woman who returned to work illustrated: “Yes, the meaning of work has changed. I do not worry as much as before and I am not working as hard as I did. That time is gone. My health is my main priority now” (P9). Several cancer survivors indicated that the meaning of work did not change at all. Yet, a few participants declared work had become more important after diagnosis and treatment. For example, a 60-year-old woman explained: “Work is more important for me now. It is satisfying to work with a certain goal, to enjoy my job and to have a salary” (P17).

Attitude towards work

Most participants expressed to have a positive attitude towards both work in general and towards their current job. However, a minority was ambiguous and reported to have both positive and negative thoughts, due to different reasons. For example, a 59-year-old man illustrated that his attitude towards his job was positive at the time he was in charge at work, in a managerial function, but that it negatively changed when he lost control of different tasks at work. This participant was not at work anymore at time of questionnaire completion. Another man with the age of 61 years who was not able to continue work as well said: “When I started to work, I was only eighteen years old. I think I have worked long enough” (P4).

Social support or pressure (not) to RTW or (not) continue to work

Participants mainly received social support to RTW or to continue working not only from their family and friends but also from their employer and colleagues. For example, some participants reported that their employer contacted them during their sick leave to support them. Participants who experienced social support often indicated that this stimulated them to RTW. A minority stressed that they received no social support to RTW. This lack of social support was caused by, e.g., family who lived too far away or an employer who did not express any interest. Sometimes, social pressure to RTW or to continue working was exerted on cancer survivors, e.g., by their occupational physician. That is, some occupational physicians enforced survivors to RTW for a certain number of hours within a certain period of time, which made them feel uncomfortable and distressed. For one or two, this type of pressure accelerated their RTW, but overall, participants had the impression it did not necessarily improve their work ability. A 50-year-old woman illustrated the support and pressure she experienced, saying: “I received support from my family and my husband to RTW. However, the occupational physician put pressure on me, while I felt too tired to work. I did not want to get into a fight with him though, so I just started working again” (P15). Considering the experience of social “pressure” not to return to work, to take it easy for a while, a major part indicated to recognize this sort of “pressure”, especially from family and friends. For example, a man aged 52 years said his wife wanted him to quit working, because his health is more important: “My wife always says: ‘if you’re not feeling well, just stop working!’” (P2).

Social norm

Many participants believed that most individuals generally enjoy their job and that working, and to be part of the society, is important to people at large. Other participants believed that a large number of people essentially works for financial reasons, but that they dislike the job they are working in. Some also indicated that they experience being occupationally active as standard and that others expect them to comply to this. A 62-year-old woman expressed finding it hard to say something about “social norm”, saying: “It is difficult to assess how other people think about work in general” (P3).

Expectations after diagnosis regarding RTW or continuation of work

Immediately after diagnosis, most participants expected to be able to RTW again or to continue working. Some of them emphasized not wanting to stay on sick leave for a long time. A good prognosis of the disease and a positive attitude towards RTW played a role as well in their positive expectation regarding their work ability. These participants assumed that “staying positive” would improve their RTW process in the end. Most participants with an unsure prognosis indicated that it was unsure when they would RTW. This uncertainty influenced their expectations about the entire RTW process. Still, a lot of them remained positive, saying for example: “I know I will RTW eventually, but I just do not know when that moment will be” (P14). Although the majority of the participants with a positive expectation did RTW, a few participants who expected to RTW, did not RTW eventually, e.g., because their prognosis had deteriorated during their treatment. Most of the participants with negative expectations about RTW or continuation of work anticipated to be on sick leave for quite some time and not to RTW on short notice. Others expected not to RTW due to their age; they considered themselves too old to RTW. For example, a 59-years-old man indicated that he was already considering to stop working due to his age. When he was diagnosed with cancer he decided to rearrange his life, reporting: “When we were driving home after receiving the diagnosis, I said to my wife: ‘now, I am never going back to work again’” (P27). Some of the participants who initially had a negative expectation regarding RTW reported a change in their expectations from negative to positive during the treatment process, most of all because they started to feel better. Nine participants stated they had no expectations at all, regarding RTW or continuation of work, immediately after diagnosis. These participants expressed a major shift in priorities, i.e., their main priority became to enjoy life and to be with friends and family.

Perceived control regarding influencing factors on RTW orcontinuation of work

Some participants believed that they were capable to control influencing factors related to RTW, such as physical complaints. For example, they indicated to have learned that physical activity could positively affect rehabilitation and, therefore, decided to start or intensify their exercise. One woman aged 50 years who returned to work responded: “I think it is hardly possible to influence RTW, except for staying physically fit” (P7). The majority of the participants believed to be in control of their psychosocial difficulties, which they considered important to handle in order to enable RTW. By setting rehabilitation goals and having a positive attitude regarding their recovery, they perceived to be able to influence their psychosocial complaints and consequently their work ability. A minority of the participants thought to be unable to control any factors in their life that could influence RTW. For example, a 61-year-old man who did not RTW illustrated: “In the past, I could do everything I wanted, but that has changed enormously. However, it does not bother me; I have accepted it” (P13).

Coping mechanism in general and at work

The majority of the participants emphasized to apply active coping mechanisms in general. According to some of these participants, they were able to cope with problems because of their active nature. Many of them used goal setting, which helped them cope. A woman aged 54 years said: “I am someone who actively tackles problems by nature” (P10). However, immediately after diagnosis, several participants indicated to be quite passive. Actively coping with the consequences of their disease or treatment appeared to be difficult for them. For example, a 52-year-old man who returned to work reported he felt “knocked-out” immediately after his diagnosis; he did not know how to cope with his situation. During his rehabilitation, he regained his active nature: “I aimed towards a certain goal (i.e., walking a famous trail); and I said to myself ‘if I achieve this goal, then I can start thinking about RTW again’” (P2). Some of the participants said to recognize themselves more in a passive coping style, i.e., not actively dealing with events in life, but just letting them be. With regard to those who were occupationally active again, the majority explained to cope with difficulties at work promptly, e.g., implementing breaks during the day to prevent work overload: “If there is a chance to take a break during work, I will immediately take advantage of that opportunity” (P13). Most of these participants clearly disclosed their physical and/or psychosocial problems to their colleagues and employer. For example, one participant said: “I explained to my colleagues and employer why I was on sick leave, arrived late or left earlier sometimes” (P3). Others described lacking possibilities or skills to cope with difficulties at work, e.g., not being able to communicate directly about problems with their supervisor.

Additional themes

Influencing factors on RTW or continuation of work

When asking participants specifically about factors they considered to have influenced their RTW or continuation of work, a wide variation of responses was given. Participants reported physical factors, e.g., fatigue, but also sociodemographic factors, e.g., age, and numerous work-related factors, e.g., type of contract, flexibility, and attitude of employer and colleagues, and whether or not receiving counseling from the occupational physician, to influence RTW. The majority of participants reported psychosocial factors to influence RTW, e.g., concerns about prognosis and influences from their social network. A number of participants indicated financial factors to be impacting their RTW as well. Being accommodated by the employer, experiencing fatigue and having a positive attitude in life were the factors participating cancer survivors considered to be most influential.

Participation in supporting programs to RTW or continuation of work

The majority of the cancer survivors participated in supporting intervention programs that were not specifically aimed at RTW, but on recovery in general. These types of programs included for example physiotherapy, occupational therapy, rehabilitation programs, or consulting a psychologist. A minority of the participants received support that focused specifically on RTW or continuation of work. Frequently, these programs were reintegration programs provided by the participants’ employer. In addition, many participants indicated that they were aware of the existence of supporting programs focusing specifically on RTW, but they did not participate in these. A minority of the participants indicated they were not aware of the existence of such programs at all.

Discussion

General findings

The aim of the present study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of cancer survivors regarding behavioral determinants of RTW and continuation of work. Some participants indicated work to be meaningful, while others mainly worked because of financial necessity. Also, whereas the attitude of most participants towards work seemed to be quite positive, some expressed ambiguity. Social support to RTW or to continue working was mainly received from family and friends, but pressure to RTW from the occupational physician was also experienced. Most cancer survivors considered working as standard, the “social norm”, but many of them were unsure about their own possibilities to RTW after diagnosis. Finally, those who attributed an active coping mechanism expressed being able to deal with work-related difficulties.

Interpretation of findings

In this study, work was found to have both an important intrinsic (e.g., personal goals; financial reasons) and extrinsic meaning (e.g., contribute to society; social interaction) for cancer survivors. These findings have been supported by previous studies, e.g., Handberg et al. [Citation31] indicated that particularly men had a strong desire to get back to work, because of financial issues and the enhanced feeling of normalcy. RTW was something that simply needed to be done to support the family or to prevent losing the job,[Citation32,Citation33] but also because of the social aspect of interaction with colleagues.[Citation33–35] However, Wells et al. (2013) indicated that negative experiences during the RTW or continuation of work process frequently led to a revision of the meaning of work. For some, RTW was not as fulfilling as hoped, because of changed life priorities or an inaccessible former level of functioning. Consequently, being diagnosed with cancer often resulted in frustration of spending valuable time at work.[Citation36] In a broader context, literature showed that cancer survivors who experience their life as meaningful report less psychological complaints and higher quality of life.[Citation37] Correspondingly, having a meaningful working life could be considered as supportive for cancer survivors as well.

Considering the attitude towards work in general and the current job, most participants indicated to be positive, which might have been a socially desirable answer. However, in the study of Noordik et al.,[Citation38] all participants, i.e., patients with mental disorders, reported to have a positive attitude towards RTW. Since being able to work, during or after treatment, is regularly a source of distraction and an opportunity to feel normal instead of a patient, the articulated positive attitudes are highly understandable.[Citation36] Therefore, a positive attitude might be a motivational factor for cancer survivors to RTW.

Previous studies showed that social support from colleagues and the employer is important to enhance work-related health and reduce sick leave in cancer survivors.[Citation39,Citation40] Correspondingly, Nilsson et al. [Citation41] indicated that a lack of social support was significantly associated with being on sick leave in breast cancer survivors. In the current study, the importance of social support, not only from persons at work but also from close relatives, was recognized by the participants. Some participants indicated to experience social pressure from their occupational physician. However, in a study by Yarker et al.,[Citation42] most survivors found occupational health services or human resources to be supportive during sick leave and upon their RTW. In the Netherlands, occupational physicians play an important role in the guidance of sick-listed employees, which is separated from medical specialists who treat patients in terms of disease. As stated in the Dutch legislation, they have a responsibility to increase participation of employees with (chronic) diseases, together with the employer, and the employee. With regard to the reported “pressure” not to RTW, cancer survivors expressed that close relatives were concerned about their RTW, which was in line with the findings of a study by Dorland et al. (2015). They suggested that this “pressure” not to RTW negatively affected work functioning.[Citation43] Therefore, social support might be regarded as an important aspect for cancer survivors to RTW.

Previous studies reported different findings on what is thought to be the social norm regarding work. In a study by Isaksson et al.,[Citation44] unemployed persons reported high levels of agreement with the norm that work should be an entitlement, which might increase the motivation to re-enter the Labor market. Saunders et al. (2014) showed that among patients with different types of disabilities, work is perceived as, for example, a part of daily life, a source of identity, and a way to provide financial support. It was suggested that these perceptions of work can encourage people to RTW.[Citation45] Consequently, positive societal perceptions regarding work can be supportive for cancer survivors to RTW or continue to work.

Positive expectations about RTW immediately after diagnosis were reported by a considerable part of the participants. In a study by Heijbel et al.,[Citation46] it was shown that the perception of employees on long-term sick leave regarding their RTW was the best predictor for their actual RTW. Mondloch et al. [Citation47] found that a positive expectation was associated with an increased chance of RTW in patients with low back pain and myocardial infarction. According to Iles et al.,[Citation19] a low expectation increases the risk of poor work outcomes in patients with non-specific low back pain. When developing future interventions to support RTW for cancer survivors, it is important to consider the expectations they have regarding their RTW.

Considering the control cancer survivors reported to have on factors influencing RTW, this is somewhat related to the concept of self-efficacy. A study by Volker et al. [Citation48] showed that self-efficacy is a predictor of RTW in long-term sick-listed employees with all-cause sickness absence. However, a study of Labriola et al. [Citation49] stated that self-efficacy cannot predict RTW among employees on sick leave in general. In our study, the majority of the participants believed to be in control of their psychosocial difficulties, which they considered important to handle in order to enable RTW. Therefore, concepts such as self-efficacy or perceived behavioral control should not be disregarded when developing work-related interventions. Specifically, survivors should be supported to take an active role in managing their vocational rehabilitation, as this may increase their self-efficacy, which in turn is associated with improved quality of life.[Citation50]

Regarding coping mechanisms of the participants, most participants reported to apply active coping mechanisms when dealing with difficulties in daily life and at work. In a study by Marhold et al.,[Citation51] an intervention to improve coping skills regarding RTW was developed for women diagnosed with musculoskeletal pain, which decreased their time to RTW. Nevertheless, Knott et al. [Citation52] showed that cancer survivors who were on sick leave for quite some time, lost confidence to cope with problems at work. Additionally, according to Rath et al. (2015), cancer survivors are more likely to have coping issues at work due to the side-effects of their disease. They suggested that counseling to develop successful coping strategies at work might be beneficial for cancer survivors.[Citation53]

When it comes to factors influencing RTW or continuation of work in cancer survivors, accommodation of the employer, cancer-related fatigue, and a positive attitude in life were regarded as highly influential. These findings are in line with those from previous studies. Spelten et al. [Citation54] found, for example, that a supportive work environment improved RTW in cancer survivors. In addition, the study of Islam et al. (2014) found that work-related factors, such as type of contract, flexibility, and attitude of employer and colleagues, could motivate breast cancer survivors to RTW and that a positive attitude in life stimulated survivors to RTW. Also, they showed that fatigue might inhibit RTW,[Citation55] which was confirmed by another study as well.[Citation43]

Finally, the majority of the interviewees participated in programs aiming at recovery in general, such as physical and psychosocial rehabilitation. In the review of Egan et al. (2013), it was suggested that within such rehabilitation programs, an increased focus on work and a liaison with an existing RTW program and resources should be aimed for. Herewith, potential work-related problems cancer survivors are confronted with during their rehabilitation trajectory may be more effectively addressed.[Citation56]

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present qualitative study is that it is the first showing different perspectives and a variety of experiences regarding behavioral determinants of RTW and continuation of work in cancer survivors. Conducting interviews is a useful method to explore findings regarding behavioral determinants from previous literature more in-depth, since these findings mostly emerged as a sub-goal or additional theme. This approach enabled the researchers to investigate behavioral determinants in a more extensive way, whereas participants were given the opportunity to comprehensively express their thoughts. Another strength is that two researchers independently performed the thematic content analysis and meticulously compared these analyses to increase accuracy.

A limitation of the present study might be that survivors have been recruited from only one specific hospital, i.e., the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital. Consequently, it is questionable whether the results of this study are generalizable to cancer survivors from other hospitals. That is, patients in this specialized cancer hospital are generally higher educated,[Citation57] which was also found in our study sample. Also, with regard to generalizability, one should bear in mind that the Dutch occupational health care system, e.g., the presence of an occupational physician, may differ from occupational health support in other countries. In addition, regarding the inclusion of participants, a possibility might be that cancer survivors with a negative attitude towards work were not willing to participate in this study and, therefore, did not respond to the questionnaire, or were not motivated to sign up for the interview. This might lead to somewhat unilateral ideas about behavioral determinants regarding RTW or continuation of work in cancer survivors. Lastly, almost all interviews were conducted via telephone, with the exception of three face-to-face interviews, which might have led to divergent results. In the telephone interviews, the internal validity may be affected as the researcher was less able to ask in-depth questions, based on non-verbal communication.[Citation58]

Implications for research and practice

Based on the findings of the current study, behavioral determinants should be taken into account in future research. That is, a cancer survivor might for example be physically able to RTW, and accommodated by employer and colleagues at work, but if after being diagnosed with cancer the meaning of work for this person has changed, a regular supportive intervention ignoring this changed meaning will continue to show insignificant results. Accordingly, negative attitudes, perceiving “not working” as the norm, a lack of social support from family, friends, but also from persons at work, should be imperative topics of interest in upcoming studies. However, the causal relationship between behavioral determinants and RTW or continuation of work in cancer survivors still has to be confirmed. Such causal relationship would also provide stronger evidence whether and which behavioral determinants should be included in the development of RTW interventions for cancer survivors.

In practice, for cancer survivors, it might be useful to start thinking about RTW early in their treatment process. Health care professionals can play a role in this, as they stimulate cancer survivors to consider RTW or, if possible, to continue working. Also, survivors’ expectations regarding RTW, but also coping strategies to apply when confronted with problems concerning RTW or difficulties at work are important to discuss at an early stage. Since only a minority of the cancer survivors participated in programs aimed specifically at RTW, it might be a task for professionals to early highlight the existence and importance of these programs.

Conclusion

Until now, the perspectives and experiences of cancer survivors regarding behavioral determinants during their RTW and continuation of work have not been explored in a comprehensive, qualitative way. The current study provides an overview of important determinants to consider in future studies. Thinking about work as meaningful, having a positive attitude and a supportive social environment, and applying active coping skills are suggested to have a significant influence. Additionally, cancer survivors’ expectation to RTW and their perceived control on factors influencing RTW are assumed to positively influence the RTW in cancer survivors. Addressing these behavioral determinants in the development of work-related interventions might result in more effective interventions and in sustained employability of cancer survivors.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Dutch Cancer Society for funding the fellowship of Dr. Saskia Duijts (VU2013–5866), which made it possible to conduct this study. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Alfons Balm, Dr. Monique van Leerdam, and Dr. Hester Oldenburg of the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital for their help regarding recruitment of patients. Finally, we like to thank Anouk Rosenhart for transcribing all interviews.

References

- Duijts SFA, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, et al. Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:481–492.

- de Boer AG. The European Cancer and Work Network: CANWON. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:393–398.

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403.

- van Muijen P, Weevers NL, Snels IA, et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22:144–160.

- McGrath PD, Hartigan B, Holewa H, et al. Returning to work after treatment for haematological cancer: findings from Australia. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1957–1964.

- Smedby KE. Cancer survivorship and work loss – what are the risks and determinants? Acta Oncol. 2014;53:721–723.

- Hoffman B. Cancer survivors at work: a generation of progress. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:271–280.

- Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:109–130.

- de Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajarvi A, et al. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301:753–762.

- van Muijen P, Duijts SFA, Bonefaas-Groenewoud K, et al. Factors associated with work disability in employed cancer survivors at 24-month sick leave. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:236.

- Taskila T, de Boer AG, van Dijk FJ, et al. Fatigue and its correlates in cancer patients who had returned to work – a cohort study. Psychooncology. 2011;20:1236–1241.

- Wagner LI, Cella D. Fatigue and cancer: causes, prevalence and treatment approaches. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:822–828.

- Steiner JF, Cavender TA, Nowels CT, et al. The impact of physical and psychosocial factors on work characteristics after cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17:138–147.

- de Boer AG, Taskila T, Tamminga SJ, et al. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD007569.

- Tamminga SJ, de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, et al. Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:639–648.

- Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, et al. A randomized trial to increase physical activity in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:935–946.

- Tamminga SJ, Verbeek JH, Bos MM, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-based work support intervention for female cancer patients – a multi-center randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63271.

- Duijts SFA, Bleiker EM, Paalman CH, et al. A behavioral approach in the development of work-related interventions for cancer survivors: an exploratory review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;24:2445–2453.

- Iles RA, Davidson M, Taylor NF. Psychosocial predictors of failure to return to work in non-chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:507–517.

- Brouwer S, Reneman MF, Bultmann U, et al. A prospective study of return to work across health conditions: perceived work attitude, self-efficacy and perceived social support. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:104–112.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Predictors of employment among cancer survivors after medical rehabilitation – a prospective study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39:76–87.

- Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, et al. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:259–274.

- Duijts SFA, Spelten E, Verbeek JH. Behavioral determinants of employment status in cancer patients. In: Mostofsky, editor. The handbook of behavioral medicine. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2014.

- Verbeek JH, Spelten E. Work. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York: Springer Science; 2007. p. 381–396.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.

- Wilkinson S. Feminist research traditions in health psychology: breast cancer research. J Health Psychol. 2000;5:359–372.

- Qualitative analysis with Atlas.ti. Version 5.2 2008.

- Friese S. Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. London: Sage; 2012.

- Handberg C, Nielsen CV, Lomborg K. Men's reflections on participating in cancer rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies 2000–2013. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:159–172.

- Midtgaard J, Hansen MJ, Grandjean B. Modesty and recognition – a qualitative study of the lived experience of recovery from anal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1213–1222.

- Cecil R, Mc CE, Parahoo K. 'It's hard to take because I am a man's man': an ethnographic exploration of cancer and masculinity. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:501–509.

- Gray RE, Fitch M, Phillips C, et al. To tell or not to tell: patterns of disclosure among men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2000;9:273–282.

- Jonsson A, Aus G, Bertero C. Men's experience of their life situation when diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:268–273.

- Wells M, Williams B, Firnigl D, et al. Supporting 'work-related goals' rather than 'return to work' after cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of 25 qualitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1208–1219.

- van der Spek N, van Uden-Kraan CF, Vos J, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy in cancer survivors: a feasibility study. Psychooncology. 2014;23:827–831.

- Noordik E, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Varekamp I, et al. Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1625–1635.

- Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work. In: Basic books, editor. Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books; 1990.

- van der Doef M, Maes S. The Job Demand-Control-(Support) Modal and psychosocial well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress 1999;13:87–114.

- Nilsson MI, Petersson LM, Wennman-Larsen A, et al. Adjustment and social support at work early after breast cancer surgery and its associations with sickness absence. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2755–2762.

- Yarker J, Munir F, Bains M, et al. The role of communication and support in return to work following cancer-related absence. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1078–1085.

- Dorland HF, Abma FI, Roelen CA, et al. Factors influencing work functioning after cancer diagnosis: a focus group study with cancer survivors and occupational health professionals. Support Care Cancer 2015 May 29.

- Isaksson K, Johansson G, Bellaagh K, et al. Work values among the unemployed: changes over time and some gender differences. Scand J Psychol. 2004;45:207–214.

- Saunders SL, Nedelec B. What work means to people with work disability: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:100–110.

- Heijbel B, Josephson M, Jensen I, et al. Return to work expectation predicts work in chronic musculoskeletal and behavioral health disorders: prospective study with clinical implications. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:173–184.

- Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW. Does how you do depend on how you think you'll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients' recovery expectations and health outcomes. CMAJ. 2001;165:174–179.

- Volker D, Zijlstra-Vlasveld MC, Brouwers EP, et al. Return-to-work self-efficacy and actual return to work among long-term sick-listed employees. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:423–431.

- Labriola M, Lund T, Christensen KB, et al. Does self-efficacy predict return-to-work after sickness absence? A prospective study among 930 employees with sickness absence for three weeks or more. Work. 2007;29:233–238.

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39:1217–1223.

- Marhold C, Linton SJ, Melin L. A cognitive-behavioral return-to-work program: effects on pain patients with a history of long-term versus short-term sick leave. Pain 2001;91:155–163.

- Knott V, Zrim S, Shanahan EM, et al. Returning to work following curative chemotherapy: a qualitative study of return to work barriers and preferences for intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:3263–3273.

- Rath HM, Steimann M, Ullrich A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Occupational Stress and Coping Inventory (AVEM) in a cancer population. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:232–242.

- Spelten ER, Sprangers MA, Verbeek JH. Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2002;11:124–131.

- Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:S8.

- Egan MY, McEwen S, Sikora L, et al. Rehabilitation following cancer treatment. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:2245–2258.

- Schagen SB, Das E, van Dam FS. The influence of priming and preexisting knowledge of chemotherapy-associated cognitive complaints on the reporting of such complaints in breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2009;18:674–678.

- Holbrook AL, Green MC, Krosnick JA. Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing of national probability samples with long questionnaires. Public Opin Quarterly. 2003;67:79–125.