Abstract

Purpose

The current study was undertaken to understand and describe the meaning of work as well as the barriers and facilitators perceived by young people with mental health conditions for gaining and maintaining employment.

Materials and Methods

Employing a purposive and maximum variation sampling, 30 young people were recruited and interviewed. The respondents were Singapore residents with a mean age of 26.8 years (SD = 4.5, range 20–34 years); the majority were males (56.7%), of Chinese ethnicity (63.3%), and employed (73.3%), at the time of the interview. Verbatim transcripts were analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Three global themes emerged from the analyses of the narratives, which included (i) the meaning of employment, (ii) barriers to employment comprising individual, interpersonal and systemic difficulties and challenges participants faced while seeking and sustaining employment and (iii) facilitators of employment that consisted of individual and interpersonal factors that had helped the young persons to gain and maintain employment.

Conclusions

Stigma and discrimination emerged as one of the most frequently mentioned employment barriers. These barriers are not insurmountable and can be overcome both through legislation as well as through the training and support of young people with mental health conditions.

Employment offers several benefits to people with mental health conditions, including improvement in economic status, self-efficacy, and empowerment.

Stigma is a significant barrier to employment for young people with mental health conditions; remaining optimistic about career prospects and getting support from peers is vital to employment success.

Disclosure of the mental health condition at the place of work is beneficial to the person’s own recovery and helpful to others; however, young people must be empowered to choose when and what they want to disclose and under what circumstances.

Families help young people with mental health conditions in achieving their employment goals by offering emotional and instrumental support, as well as motivating them to accomplish more.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Employment has been defined as “work you get paid for” [Citation1]. Employment addresses the practical need for income, provides access to resources, helps in achieving social contact and support, and, gives an individual a sense of purpose and identity [Citation2–4]. Employment offers similar benefits to people with mental health conditions, wherein work is associated with improvement in the economic position [Citation5], self-efficacy [Citation6], and empowerment [Citation7]. Studies have also found that employment is associated with better clinical outcomes among people with mental health conditions. [Citation8–10]. In an interventional study on patients with severe mental illness, Burns et al. [Citation8] found that those currently working were associated with having better global functioning in terms of symptoms and disability on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale, as well as better subjective quality of life, as compared to those not working. Given these advantages, work is routinely promoted in both clinical and health policy settings for people with mental health conditions [Citation11].

However, rates of unemployment remain high among persons with mental health conditions, with these rates often reflecting the severity of the illness. Burnett-Zeigler et al. [Citation12] used a longitudinal design to examine the effects of psychiatric and substance use disorders on employment outcomes across two waves of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol-Related Conditions conducted three years apart. The study found that among those employed at baseline, 12-month depression, bipolar disorder, and drug dependence were associated with decreased odds of being employed at follow-up. Lerner et al. [Citation13], using baseline and 6-month follow-up, found that at follow-up, persons with depression had more new unemployment. New unemployment was 14% for persons in the dysthymia group, and 12% for persons in the major depression group. In comparison, new unemployment was 2% for persons in the control group.

Among those with mental health conditions, the rates of employment are even bleaker for those with schizophrenia, which are universally less than 20% [Citation14,Citation15]. The “health selection” perspective suggests that differences in health lead to differences in socioeconomic status. For those with mental health conditions, the public stigma and employment inequalities pose a significant barrier in their pursuit of employment [Citation16,Citation17]. People with mental health conditions frequently report being turned down for a job when they disclose their condition [Citation18,Citation19] or do not look for work because they anticipate discrimination [Citation20]. Owing to the stereotypical belief that those with mental health conditions are competent only for specific jobs, they are often underpaid or given temporary jobs that are not commensurate with their skills and education. These situations can lead to self-stigmatization and erosion of self-confidence, discouraging further job-seeking [Citation21]. Disclosure of a mental health condition in the work-place can also lead to prejudice and discriminatory behaviors from supervisors and co-workers, such as lack of trust and career advancement opportunities, harassment, and social exclusion [Citation22]. Mental health conditions often impair cognitive functioning and thus limit the ability of people with severe illnesses to learn and perform effectively at work [Citation23]. Medication side-effects like drowsiness and restlessness can further compound the problem [Citation24]. Due to all these reasons and more, people with mental health conditions often find themselves unemployed for prolonged periods.

Barriers and opportunities for seeking employment vary across age. A recent report by the United Nations indicated that participation in the global labour force has been decreasing since the 1990s, mainly as a result of increased life expectancy, rising retirement age, and expansion of workers in informal employment (resulting in increased official unemployment) [Citation25]. Employment among young people (15–24 years) has declined sharply, falling by 15 percentage points from 1993 to 2018 [Citation26]. Factors for this decline include extended education that delays workforce entry, skills mismatch, lack of work experience, and an increasing reliance on technology by organisations resulting in worker dislocation [Citation25]. Research further suggests that the effects of unemployment in a person’s early working career is likely to have a long-term “scar” in terms of a penalty on their later-life employment prospects and wages [Citation27]. The current COVID-19 pandemic has further compounded unemployment, especially among youth. A global survey by the ILO found that over one in six young people surveyed had stopped working since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. The report estimated that compared to the last quarter in 2019, working hours had declined around 10.7%, in the second quarter of 2020, which is equivalent to 305 million full-time jobs [Citation28].

Transitioning from education into employment and establishing a career is thus challenging and an important milestone for a young person. For those with mental health conditions, these challenges are even more imposing. The age of onset of mental health conditions is usually early which results in significant disruption of education and social development [Citation29,Citation30]. Students with mental health conditions have extremely high school drop-out and failure rates [Citation31]. Many young people with mental health conditions live with their families, and family members may often be overcautious due to concerns about work-place stress and vulnerability to potential relapse, thus deterring the young person from seeking employment [Citation32]. Childhood and adolescent-onset mental health conditions are often associated with a longer delay in treatment as compared to early adult-onset conditions. This treatment delay results in a more severe course of illness with marked impairments in occupational and social functioning [Citation33,Citation34], which further hinders the completion of education and attaining employment.

Singapore has enjoyed a strong labour force participation rate since 2015. The employment rate for residents aged 15 years and above increased from 65.1% in 2018 to 65.3% in 2019. Data from 2019 revealed that among youth (15–24 years), employment rates declined from 34.5% to 33.9% amidst greater caution in hiring [Citation35]. Data on unemployment among people with mental health conditions in Singapore are similar to existing literature. The Singapore Mental Health Study (SMHS) conducted in 2010 among adult Singapore residents revealed that the rate of unemployment among those with mental health conditions was 11.1%, which was significantly higher than the 6.7% rate of unemployment among those without them [Citation36]. A study among patients with first-episode psychosis in Singapore found that among those aged 16 to 40 years, 44.5% were unemployed when they first sought treatment with the programme [Citation37]. However, there has been little research in Singapore, exploring employment needs and the challenges faced by young people diagnosed with mental health conditions. The current study was undertaken to understand and describe the meaning of work as well as the barriers and facilitators perceived by young people with mental health conditions for gaining and maintaining employment.

Materials and methods

Study design

This research was part of a larger mixed-methods study that examined the employment needs of young people with mental health conditions from a multi-stakeholder perspective. The study comprised semi-structured interviews with young people with mental health conditions, their caregivers who provided informal support, as well as employment specialists, and other professionals who provided formal support to help these young people gain employment. Interviews were also conducted with employers and co-workers of young people who may or may not have had experience of working with someone with a mental health condition. In all, 130 interviews were completed and analysed. The quantitative study consisted of a survey conducted online with 150 employers in Singapore to understand their attitudes towards hiring young people with mental health conditions.

Sampling and participants

The study employed a purposive and maximum variation sampling [Citation38] to select study participants who varied by age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, and duration of illness. All participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (i) aged between 18 and 35 years [Citation39], (ii) Singapore residents, (ii) diagnosed with a mental disorder (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) citeria) [Citation40] except substance abuse, (iii) being a mental health service user, (iv) either employed or unemployed, and (v) able to provide informed consent. The study was conducted at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore, which is a tertiary hospital providing care to people with mental health conditions. Clinicians and case managers involved in the study informed their patients of the research study and procedures. If patients were interested in participating, their relevant personal details were shared with the research team for establishing contact.

In all, 30 participants were recruited. The mean age of the participants was 26.8 years (SD = 4.5). The majority of the participants were male (56.7%), of Chinese ethnicity (63.3%), had a Polytechnic diploma or a university degree (56.7%), were single/never married (90%), employed (73.3%), with a mean duration of employment of 1.6 (SD = 1.8) years (employment duration ranged from 3 weeks to 6 years). The majority were holding an entry-level job (60%) and less than half of them were earning an average income of above SGD 1000 per month (40%). provides details on the participants’ background.

Table 1. Socio-demographics of young persons with mental health conditions.

Interview procedures

Face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted with the participants at a mutually agreed upon venue and time. The participants preferred to be interviewed at the Institute of Mental Health during their visit to the hospital for their scheduled medical appointment. The interviews were conducted by trained qualitative interviewers who provided an overview of the study’s purpose and obtained written consent from each participant. Participants also completed brief demographic data forms. Each interview lasted between 1 and 1.5 h. Interviews were conducted using an interview guide (see ); non-assumptive probes and follow-up questions were used to encourage participants to elaborate and provide examples from their own experiences. Interviews were conducted in English and transcribed verbatim. English is one of the four official languages in Singapore, and it is the main language of instruction in local schools. The majority of young Singaporeans are thus well-versed in English. Interviews for data-gathering continued until data saturation was reached at the 26th interview. Four more interviews that had been scheduled were completed to ensure that data saturation had been achieved, and no new themes emerged. Participants received an inconvenience fee of SGD 60 after completing the interview.

Table 2. Interview guide for young persons with mental health conditions.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board. Written informed consent was taken from all participants prior to the interview, which included consent to audio-record the interviews.

Coding and data analysis

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed and imported into NVivo 11 software for purposes of coding and analysis. The study used thematic analysis [Citation41]. The authors involved in the coding (MS, SS, ZY, and PS) read and re-read the initial five transcripts in order to identify potential themes. This process of “repeated reading” [Citation41], resulted in data immersion and ensured the researcher’s closeness with the data. The themes were then forwarded to the lead author. The second level of analysis involved these authors reviewing the basic themes and finalizing them based on the frequency and similarity of responses. These themes were then used to develop a codebook that had been mutually agreed on by all the coders. The codes were written as suggested by Boyatzis [Citation42], and each code was described by the following: label, definition, inclusions and exclusions, and examples of typical and atypical codes from the raw data. Coding of the same transcript among all the coders commenced immediately after the first draft of the codebook had been finalized for the purpose of achieving optimum inter-rater reliability. This process was reviewed and repeated (with another transcript) until Kappa scores were above 0.70.

Once optimum inter-rater reliability was achieved, coding of all transcripts was done by the specified coders. Further coding also took place at this stage to ensure no themes had been missed in the earlier stages. If new themes emerged, they were highlighted and included by all the coders. After coding all the transcripts, the coders met again to discuss and decide how to retain the diversity of the basic themes, while producing overarching themes. Basic themes were combined based on their interrelation and co-occurrence in the interviews to produce organizational and global themes of relevance to the employment of people with lived experiences of mental health conditions. This was achieved by eliminating redundancies, discarding minor/irrelevant themes, and merging closely related major themes.

Results

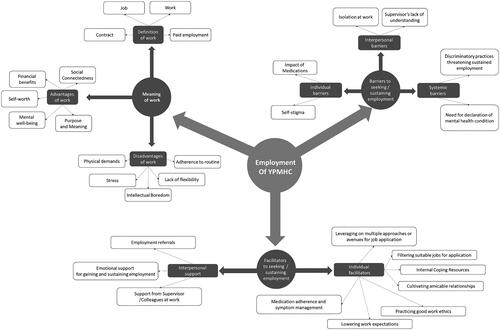

Three global themes were identified from the data. The basic, intermediate and global themes are illustrated in the thematic map as shown in . The verbatims have been minimally edited for readability. The details of the participants have been provided in brackets as Subject ID/Age (in years)/Gender (Male or Female)/Employment status (Employed/Unemployed/Student).

Figure 1. Thematic representation of meaning, barriers and facilitators of employment for young people with mental health conditions.

Meaning of employment

This global theme refers to how participants defined employment and include the advantages and disadvantages of employment perceived by them based on either their own or others’ experience. Participants described employment as a “job,” “work,” “contract,” and “paid position.”

Advantages of employment

Almost all participants (28 of the 30) described the importance and benefits of work, which ranged from financial benefits enabling them to meet their day-to-day expenses, to “work” providing them with a purpose in life. One of the main advantages mentioned by participants was the association of employment with wages or the ability to earn money. They talked about the need for money to meet their basic requirements such as food and shelter and also as a means of achieving economic stability, which gave them the ability to support themselves and their family. Participants also pointed out several benefits of work to their mental well-being. This included references to the positive impact of interactions with colleagues and the distraction provided by work that made them focus on getting the job done and allowed them to forget their symptoms or problems. They also saw work as a way of stimulating their intellect, thus keeping them mentally alert and healthy. Some of the participants felt that employment contributed to one’s sense of self-worth and gave them a sense of purpose and meaning in life. They felt that being employed gave them a sense of identity and normalcy in that they were no longer ill and capable of doing what “others” of their age or background were doing. Participants also talked about how their jobs meant something more than just drawing a salary. They talked about having a sense of accomplishment and achievement through their work. Other participants, on the other hand, saw employment as a way of getting to know people. Participants talked about how they had met and made friends with people at their place of work and felt that being employed widened their social circle. Interestingly, some saw employment as a way of contributing to society. They felt that they were productive members of the community rather than being dependent on others for their welfare. Two participants said that paying income tax gave them a sense of achievement, that is, that they were now contributing to various social initiatives and projects.

It means having a stable income, then, you’re self-reliant, able to support yourself, then you may also be able to support your family financially. (YP12/21/F/Unemp)

Sometimes you tend to think negatively at home, but if you go out and work, you will not think negatively, and you meet nice people, you will feel happy. (YP16/27/M/Unemp)

A new sense of identity as in like you feel normalized. (YP09/26/F/Emp)

You have a sense of purpose, so you kind of know that you are doing something with your life. Erm … sense of fulfilment because you know, you, go to work, and you have achieved something, you know delivered some kind of service or product to someone and there is some satisfaction that comes from that I guess. That is important because you need to feel your life has some purpose. (YP18/33/F/Emp)

I think if it’s a fun job and very friendly I mean as in you can meet a lot of new people, talk to them ya. (YP07/21/F/Unemp)

……and be more involved in the social development of the country, economic development of the country. (YP10/31/M/Emp)

Disadvantages of employment

Most of the participants (25 of the 30) mentioned disadvantages of employment that included the physical and emotional demands of the job. Participants mentioned feeling tired or drained because of their job. The long work hours led to a lack of time for themselves and was seen as a hindrance to the pursuit of their own interests and hobbies. Some of the participants also talked about work-related stress, which was contributed to by the nature of their work, work culture and colleagues. A few participants felt overqualified for the job, as they had taken on a lower level position due to their mental health problems that subsequently led to intellectual boredom. A few participants also identified the lack of flexibility and freedom to do what they wanted and having to adhere to the job requirements and routine. However, disadvantages, while perceived as annoying and frustrating, were not stated as outweighing the advantages by any of the participants.

In Singapore it’s difficult to balance between work commitments and various other commitments. So time-wise, it’s pretty stretched and uh it’s sometimes difficult to juggle between all these different kinds of commitments that we have and employment is such a big thing so it can deter us from uh looking at other things that are more important but we have less time for those things. (YP26/25/F/Emp)

Because it’s like you know once you start working you will literally have no life yes… You go (laughter) it’s true I mean Monday to Friday you will be working if you’re lucky you’re working on Monday to Friday 8 to 5 that kind of shift but you understand if you work from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m … you technically can’t do anything else. (YP04/25/M/Student)

Barriers to employment

This global theme refers to some of the difficulties and challenges participants faced while seeking and sustaining employment. It was classified broadly into the organising themes of individual, interpersonal and systemic factors. Details of the basic themes categorized under each organising theme that posed a challenge to participants in their effort to find or continue work are included in . The key intermediate themes are elaborated below.

Individual barriers

Individual barriers were endorsed by most of the participants (27 of the 30). They primarily included references to the impact of the participant’s mental health condition on their working potential and self-stigmatising beliefs held by them. Participants talked about their symptoms, and the side-effects of psychiatric medications that made them sleepy, edgy, or restless on the job, impeding their ability to work for long hours. Some of them felt that their mental health condition or medication impaired their ability to focus and pay attention at times. Almost all participants held self-stigmatising views about their prospects of gaining or maintaining employment. The belief that employers would prefer not to employ people with mental health conditions was almost universal among the participants. Many participants attributed this to the tough job market and demand for high productivity in Singapore. They felt that employers would hesitate to employ someone who they saw as “at-risk” of falling ill and not contributing to the job, as this would impact the profitability of the company.

…because the medicine makes people sleepy or restless, So I… For the past few years I’ve been fighting to not sleep in my work-place, cause it was every time you need to eat the medicine in the night so I have…uh… My body still can’t take it. the restlessness or the sleepiness. (YP05/22/M/Emp)

……and it’s like, even before you start the job you’re already …you know, killing yourself by you telling the employers you already have a negative side of you. I mean why would an employer want to hire you when you already have… I rather hire someone with neutral rather than minus 1 score. (YP25/31/M/Emp)

Interpersonal barriers

Interpersonal barriers relate to interpersonal interactions at the work-place either with co-workers or with supervisors (described by 10 out of 30 participants). Participants reported feeling left out or isolated at their places of work. They felt that co-workers tended to have limited interactions with them or, at times, avoided them altogether. While for some, these experiences followed the disclosure of their mental health condition, other participants felt they were not included in pre-existing cliques or groups from the very onset, that is, when they joined the work-place. A frequent issue brought up by participants was that their supervisors misunderstood them as they did not have a good understanding of mental health conditions, which added further stress to participants’ working life. Many participants described their supervisors as having unrealistic expectations of them, being unforgiving of their errors, and blaming these errors on their mental health condition rather than attributing it to inexperience.

……I guess word went around that I have this thing and yeah I think ever since then I went back right, I did notice that uh, some people just didn’t talk to me anymore. (YP22/30/F/Emp)

……Even then they seem a bit apprehensive they were like are you sure you are ok? Did you take your medication? Are you seeing a doctor? (YP17/21/M/Unemp)

Systemic barriers

These comprised societal or structural barriers that restricted or limited access to resources or opportunities in employment. These barriers included policies, organizational practices, and societal attitudes towards persons with mental health conditions that hinder young persons with mental health conditions from gaining and sustaining employment. The need for disclosure of mental health conditions in job applications was a point of much frustration for almost all participants (29 of 30). The majority of participants (20 of the 30) reported that by disclosing their mental health condition, any chance they had of gaining entry into the workforce was immediately eliminated. While there were instances when young persons with mental health conditions were shortlisted for job interviews despite disclosing their mental illness, employer biases placed further hurdles to their employability. One participant described a potential employer who was so fixated on his disclosure that the whole interview was dominated by questions about his 'mental illness' with no discussion of his abilities and capacity to do the job. Subsequently, he stated, he was not offered the job.

……I say I got depression they say ok I will contact you again…… (YP02/32/M/Unemp)

……firstly when I came into the room they will ask me that question, the illness part. They will ask me like what is this illness? So I’ll answer them fully, everything. So they will ask me like how did you get this illness? Then I explain to them then after that the rest of the interview is only about the illness only… (YP05/22/M/Emp)

Some participants (10 out of 30) stated that even after gaining employment, discriminatory work-place practices made it challenging for them to continue working. The respondents felt that the employers who hired them perceived the hiring as an act of charity and subsequently discriminated against them based solely on their mental health conditions. Examples of such practices included a lower pay scale being offered to people with mental health conditions (versus what was the norm for that job grade), differential treatment and opportunities, and lack of job security. Respondents complained that employers often assumed what they were capable of or what they needed without discussing or exploring their preferences. A few participants described employers who underestimated their ability to contribute or were cautious in giving them responsibility or jobs that were perceived as stressful. They felt employers often limited their jobs to simple tasks. Thus, they were not given opportunities that other colleagues without mental health conditions were given. The participants felt that doing such low-key jobs would lead to a complete lack of or slow career advancement. For young persons with higher qualifications and greater career aspirations, such practices left them feeling dissatisfied, unappreciated, bored, frustrated, and disempowered. Many participants also lamented the profit-oriented culture of some organisations. They described such organisations as having strict productivity margins and that they struggled to keep up with the high pressure. They worried about their job security as they recognised that the quality and quantity of their work were affected when they were unwell. They also described environments that were rigid, unempathetic, and unaccommodating of their condition and employers who seemed unwilling to work out a viable solution with them.

……I was only allowed for the lower pay rate instead of the market normal rate. (YP03/23/F/Emp)

I feel like it was like an empty hope like that. Because like maybe they think oh because we are accepting those with mental illness then the job cannot be too difficult. I don’t know I found it like while they are trying to make things easier for us, I feel it’s like in a negative kind of way. (YP12/21/F/Unemp)

……some organisations are like, you’re always late, you’re affecting my productivity, no, I don’t want you. (YP26/25/F/Emp)

Facilitators of employment

This global theme comprised individual and interpersonal factors that helped young persons with mental health conditions to seek and sustain employment.

Individual facilitators

These represent the plans and actions undertaken by young persons in order to navigate the maze of challenges both in gaining and maintaining employment. Different themes relating to individual facilitators emerged, which were based on the stage of the young person’s employment journey, from seeking employment to sustaining employment. The majority of the participants (20 of the 30 participants) were looking for jobs at the time of the interview. This included both participants who were unemployed as well as those working part-time or in contractual positions at the time of the interview. All participants (30) mentioned employing multiple strategies while looking for a job. These included leveraging on multiple approaches or avenues for job application. Participants mentioned getting good results from their job search through online job portals or university job portals (those who were fresh university graduates). They also stated that simultaneous multiple online job applications were an effective way to increase the chances of getting a job. Other participants searched for employment opportunities through newspaper advertisements and walk-in interviews. Some participants tried to find work by looking through job fair advertisements on various community platforms or by registering at the government-run job centres. Furthermore, being involved with various organizations such as voluntary welfare organisations (VWOs) provided some participants with voluntary work, which they felt was a positive experience that would prepare them for future competitive employment.

On the other hand, some participants adopted a very organized approach for job hunting that involved attending workshops that strengthened their skills in writing a professional resume, creating portfolios, improving software skills, and preparing for interviews to enhance their job prospects. Some of the participants stated that they searched for and shortlisted specific jobs that enabled them to work part-time or for flexible hours. They preferred jobs with hourly pay and those that involved easy and less demanding tasks, as these would help them to hold on to their jobs as they continued to experience symptoms of their mental health condition and medication side effects. These arrangements eased their worry about having to cope with starting full-time work directly from a state of complete unemployment and their concerns about not being able to commit to a job on a long-term basis due to their mental health challenges.

I saw a function where they upgraded it (the employment related website) so that you know you can just tick on certain positions and then just multi-send at once that kind so what I did I did so hey I didn’t know how I hit, who I shoot to. I hit all those … so just try … then see how… (YP04/25/M/Student)

I referred to the newspaper or the web… XX website. I found all these jobs from the XX website or newspaper. And then I contacted the person immediately using my handphone and I enquired about the job and ask them whether I can … start the job. (YP10/31/M/Student)

……same time because I feel that in my case I need to polish up my resume … I actually started compiling my resume since after… after my army……. (YP04/25/M/Student)

I also enjoy driving. And really the flexibility is VERY important for me. The ability to just switch off and go home is very important. Because some days I get bad days, I just try to end earlier and I don’t have to answer to somebody which helps. I don’t- I’m not responsible in that sense. (YP28/30/M/Emp)

Study participants who were employed specified four main strategies they applied to sustain their current job (18 of the 22 employed). They mentioned drawing upon internal coping resources for successful job maintenance such as positive thinking, anger management, and acceptance of one’s condition as a part of one’s own identity. These participants described adopting a “survivor” attitude wherein they refused to allow their struggles with their mental health condition to overwhelm them. They were determined to manage the symptoms of the illness as much as possible by seeking professional help whenever needed, adhering to the prescribed medications, and self-managing the symptoms by modifying their behaviors and believed that they were like any other young person seeking employment. Most of the employed participants endorsed good work-place relationships with co-workers, a supportive work environment, and positive work experiences as playing a significant role in having longer job tenures. Participants stated that they made a determined effort to cultivate amicable relationships at their work-place. Some of the participants believed that practicing good work ethics such as prioritizing work and demonstrating goal-oriented actions were of utmost importance in sustaining employment. They believed this would leave a good impression on both colleagues and supervisors, who would reciprocate by working well with them.

Some of the young persons with mental health conditions were aware of the limitations imposed by their condition on their work capabilities. This awareness had led them to lower their job-related expectations and to make career compromises (12 of the 30 participants). Participants reported seeking jobs or opting for less skillful, entry-level positions with salaries not matching their qualifications. A few even refused promotions and career advancements as they were worried that it would lead to an increase in job-related stress and a lack of job flexibility. They thus chose to remain in a job for which they were over-qualified rather than taking on a job which was commensurate with their qualifications or their ability in an attempt to sustain employment.

I think everybody has their drawbacks, mine is I have a mental condition but I feel that you shouldn’t uh, shouldn’t let it be an excuse not to … lead a normal life just, just try to be independent. (YP29/31/M/Emp)

……focus on what you do, focus on your responsibilities. Er… Never give up, in whatever you do. Always follow the rules and regulations of the company … Have a strong bond with your colleagues. That’s important. (YP05/22/M/Emp)

……attendance. I also come for work to show the boss that I always come like say work impression… work hard… prioritize like … first thing first … your work comes first then other thing can be like err… prioritize work. (YP14/24/F/Emp)

I understand that I have to take my medicine every night … So just to keep it in track. I just take my medicine I’ll be fine. So far I keep to myself that I can’t have that feeling of anger. Once I have the feeling of anger it will trigger. Whenever I have anger I just relax one corner, don’t talk about it, go smoke or what, just relax, don’t think about it, that’s how I control myself. (YP21/34/M/Emp)

…… in fact they want to groom me to become a senior, which I really didn’t want I rather be a trainee. (YP13/23/F/Emp)

Interpersonal support

Young persons with mental health conditions acknowledged that they received support from people in their social network for both gaining and sustaining employment (16 of 30 participants). While participants commonly utilized formal methods to search for employment, referrals from family, friends, and case managers were also frequently mentioned. Usually, friends and family (informal support) were the first people to provide participants with referrals. The majority of participants were attending rehabilitation programmes in a tertiary psychiatric institution, and they sometimes received their employment referrals from their peers. Participants also mentioned receiving emotional support and motivation from family members in their journey to gain employment. The support was usually expressed in the form of concern when participants failed to get a job or lost a job. Family members also motivated them by highlighting the financial benefits of employment to encourage them to continue looking for jobs or to apply for better jobs.

Some of the employed participants (8 of 22 participants) described getting support from their co-workers and supervisors, which proved helpful in improving their work experience and performance. For example, one participant mentioned how she was encouraged and guided at the work-place by her reporting officer. At the same time, another had a supervisor who showed empathy and provided support after learning about her mental health condition. Those who were working in a mental health setting talked about feeling safe and supported by fellow staff and colleagues. Another participant said that he felt at ease when his supervisor focused mainly on the work rather than the possible impact of his mental health condition on his work, creating a sense of job security for the participant.

Aside from my family, I know one of my cousins introduced me to a couple of people who might have job openings. (YP18/33/F/Emp)

I emailed them because I have a Peer Support Specialist who actually gave me the contact to email. (YP13/23F/Emp)

For myself, now I got some motivation from my parents and my brother ah. Actually, not from my brother, my parents … They keep on pushing me… not push, but keep advising me to keep searching for a job even though I have some mishaps going for interviews everything. But with the help of my parents, they motivate me to search for more positions and jobs all that. (YP05/22/M/Emp)

I guess they’re quite the quiet type but they’ll ask whether I’ve gotten the job so I guess that’s their concern-that’s their way of showing their concern. Like constantly checking up how’s like my progress at work, whether I’ve gotten the position or not. (YP08/22/M/Emp)

The boss is very encouraging. And then there are three persons that actually I know that actually really take care of me and show me how to do coding, the barcode, and which is the ticketing, and how to do shelving and facing, and how to arrange things neatly in the manner. (YP13/23/F/Emp)

Until yeah my manager kind of talked to me a couple of times, he knew what I was going through, he doesn’t know about the problems but he knows I had depression everything this year. He was kind of, he said he’s been through what I’ve been, he says he knows what it’s like. So, he’s kind of supportive. (YP25/31/M/Emp)

Discussion

The interviews with young persons with mental health conditions not only helped to identify barriers and facilitators of employment but also emphasised the importance of employment as perceived by the participants, and elucidated the strategies they used to gain and maintain employment. Young persons with mental health conditions echoed the importance of work for the mental health and well-being of individuals. The benefits of work were clearly articulated by the participants, who stated that it is a significant component of their life and provided them with economic security, personal and social identity, connectedness, and an opportunity to make a meaningful contribution to the community. Similar findings have been identified in several studies as evinced by a systematic review of qualitative research exploring the experience of returning to work for people with mental illness [Citation43]. Thus, our study contributes to the evidence base that young people with mental health conditions in Singapore perceive multiple benefits of work. Many of the advantages articulated by young people, such as gaining self-worth and a sense of purpose through employment, are closely associated with the concept of recovery for young people [Citation44], which further strengthens the need to focus on the employment needs of this population.

Nevertheless, and similar to other studies, participants also mentioned several disadvantages of work such as stress, tiredness, and lack of time to pursue other interests [Citation45,Citation46]. Many of these disadvantages mentioned by participants were general disadvantages of full-time employment and not specific to someone with a mental health condition. However, the fact that most of the participants were actively job-seeking gives credibility to their expressed interest in employment and perceiving it as beneficial, despite the stated disadvantages.

Similar to findings from research elsewhere, significant barriers to gaining and sustaining employment were highlighted by these young persons with mental health conditions [Citation43]. The most frequently referenced and salient barrier to employment in this study was the stigma towards mental health conditions. Decades after Goffman’s work on stigma and mental illness [Citation47], it is apparent that stigma still has a powerful impact in the area of employment of people living with mental health conditions. Structural stigma was defined by Hatzenbuehler and Link [Citation48] as “societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies that constrain the opportunities, resources, and well-being of the stigmatized.” Hatzenbuehler [Citation49] further argues that structural stigma generates and perpetuates individual-level stigma processes, such as concealment and self-stigma.

Participants in our study similarly expressed their apprehension, dislike, and reluctance for the need to declare their mental health condition to potential employers. Many felt that it would result in them not even being given an opportunity for an interview. This often acted as a deterrent for them to declare their mental health condition, which in itself can lead to anticipatory stressors and fears that they often face should they disclose their condition [Citation50]. This study also found that participants tended to self-stigmatise themselves, resulting from social stereotypes where salience was given to their psychiatric diagnosis over all other personal qualities and characteristics. In turn, this resulted in some of them believing that employers would prefer not to employ people with mental health conditions, as well as in them lowering their work-expectations.

Participants also described the effects of the illness and the side-effects of medications as barriers to employment. Other studies have similarly described the impact of the illness, like difficulties with social interaction, mood disturbance, cognitive decline, and side-effects of medications as a barrier to employment [Citation24,Citation51,Citation52].

While young people with mental health conditions acknowledged the existence of barriers related to stigma and medication side-effects, they were mostly self-sufficient in looking for and identifying suitable jobs. They used strategies similar to those used by young people in general, in looking for jobs, such as using job portals, newspaper advertisements, going for walk-in interviews, and using personal contacts [Citation53]. They also attended workshops to learn and improve their employability skills. Van Niekerk similarly reported that the personal decision to work and the determination to overcome social barriers both enhance employment opportunities in people with mental health conditions [Citation51,Citation54].

Young people with mental health conditions in our study also described employing various strategies to ensure that they stayed gainfully employed. These included taking their medications regularly, coping actively with setbacks, and maintaining exemplary work ethics. They also talked about the role played by their families, which facilitated their job-seeking. A study from Kenya similarly identified supportive family and friends as the highest facilitator of employment among people with mental health conditions [Citation24]. Wolfe and Hall [Citation55] identified role modelling, career planning, help in job searches, and supporting job decisions as some important ways in which families can support people with intellectual disabilities with employment. Our results emphasise the need for both psychoeducation and family therapy that can help caregivers provide employment support in a non-judgmental and non-authoritative manner.

While participants employed strategies drawing upon their strengths and resources to gain and sustain employment, their narratives suggest that employment remains a challenging area. Poor employment outcomes have been reported across multiple countries for people with mental health conditions [Citation56,Citation57]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [Citation57] has proposed certain key policy principles to tackle unemployment among people with mental health conditions, some of which are applicable to overcome the barriers articulated in our study. These include a focus on early diagnosis and treatment to improve outcomes, that is, reduce symptoms, improve functioning and prevent long term sequelae of mental health conditions which in turn improves employability. Incorporation of techniques like motivational interviewing [Citation58] and augmenting rehabilitation with cognitive remediation therapy [Citation59] could further help improve vocational outcomes for young people with mental health conditions. Evidence-based practices like the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) scheme should be adapted locally and evaluated for effectiveness [Citation60]. IPS comprising rapid commencement of career planning, job research, job searching, and job placement with time-unlimited on-going post-placement support may be particularly relevant for young people with mental health conditions.

Tackling stigma is another critical effort that has been emphasized by the OECD guidelines. Based on their own experiences, participants in our study were aware that employers lacked awareness and understanding and were not comfortable managing people with mental health conditions in the work-place. The education of employers and co-workers is a much-needed intervention that can overcome the fear of the unknown and improve their attitudes towards young persons with mental health conditions [Citation61]. Work-place seminars would be useful in improving knowledge and understanding of mental health conditions. Collaborating with healthcare providers to deal with possible crises that an employee may experience could ensure that co-workers and employers feel comfortable and supported when working with people with mental health conditions. Anti-stigma campaigns, which create awareness and acceptance of people with mental health conditions in the work-place, could be yet another way to improve work-place inclusivity [Citation62].

Protective legislation is another way to ensure that people with mental health conditions get fair access to employment. In Singapore, the need for job applicants to declare their mental health condition was declared to be discriminatory only in 2020 and has since been removed from institutional practices [Citation63]. This is a significant step towards facilitating the employment of people with mental health conditions across all sectors. However, reports of work-place discrimination are common despite protective legislations being in place. Participants of a cross-national study (across 30 countries) who had an episode of depression were asked about their anticipated and experienced discrimination; about 14% of them reported being mistreated when finding a job, and 23% reported unfair treatment at their work-place [Citation64]. Similar findings were reported by 5924 mental health service users in England, where 25.6% of them said that they had experienced discrimination in at least one work-related domain [Citation65]. Thus, legislation alone is not sufficient to address stigma. To ensure lasting change, a coordinated and sustained effort to improve access to mental health services, and work-place campaigns to address the negative attitudes of employers and co-workers towards people with mental health conditions is needed [Citation66].

Limitations

Limitations of the current study include the fact that all the participants were recruited from a tertiary psychiatric institution. Therefore the findings may not apply to young people with mental health conditions in general. While the participants did not know any members of the research team, referrals from the clinical team may have resulted in socially desirable replies and under-reporting of treatment-related barriers. While every effort was made to recruit participants across a range of conditions and backgrounds, very few of the participants were in managerial or equivalent positions. Thus the views of this group are under-represented. Lastly, we did not sample participants based on symptom severity; the clinical team referred only participants who were considered clinically stable and able to participate in an hour-long discussion to the researchers. The researchers also ensured that only participants who were cognitively capable of understanding and consenting were recruited in the study. These steps resulted in a fairly homogenous sample in terms of symptoms and functioning; however, we might have missed those with more severe symptoms, who may perceive more barriers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found that employment barriers for young people with mental health conditions are diverse and include individual, interpersonal and systemic factors. The most frequently mentioned employment barriers in this study were interpersonal and systemic in the form of stigma and discrimination towards people with mental health conditions. However, it is important to recognize that these barriers are not insurmountable and can be reduced or overcome. Supporting young people through vocational rehabilitation programmes, campaigns to reduce work-place stigma, and judicious use of legislation can help reduce the barriers to employment and result in significant improvement in the social inclusion of young people with mental health conditions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the participants of this study for sharing their experiences and thoughts during the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Boardman J. Work, employment and psychiatric disability. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2003;9(5):327–334.

- Boyce M, Secker J, Johnson R, et al. Mental health service users’ experiences of returning to paid employment. Disabil Soc. 2008;23(1):77–88.

- Kennedy-Jones M, Cooper J, Fossey E. Developing a worker role: stories of four people with mental illness. Aust Occ Ther J. 2005;52(2):116–126.

- Olesen SC, Butterworth P, Leach LS, et al. Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health: findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:144.

- Cook JA, Blyler CR, Leff HS, et al. The employment intervention demonstration program: major findings and policy implications. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(4):291–295.

- Liljeholm U, Bejerholm U. Work identity development in young adults with mental health problems. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;27(6):431–440.

- Bejerholm U, Björkman T. Empowerment in supported employment research and practice: is it relevant? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(6):588–595.

- Burns J, Catty J, White S, et al. The impact of supported employment and working on clinical and social functioning: results of an international study of individual placement and support. Schizophr Bull. 2008;5:949–958.

- Perkins DV, Born DL, Raines JA, et al. Program evaluation from an ecological perspective: supported employment services for persons with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005;28(3):217–224.

- Schneider J, Boyce M, Johnson R, et al. Impact of supported employment on service costs and income of people with mental health needs. J Ment Health. 2009;18(6):533–542.

- Department of Health, Australia. Fourth national mental health plan: an agenda for collaborative government action in mental health 2009–2014 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available online at https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/9A5A0E8BDFC55D3BCA257BF0001C1B1C/$File/plan09v2.pdf

- Burnett-Zegler I, Ilgen MA, Bohnert K, et al. The impact of psychiatric disorders on employment: results from a National Survey (NESARC). Community Ment Health J. 2012;27:1–8.

- Lerner D, Adler DA, Chang H, et al. unemployment, job retention, and productivity loss among employees with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1371–1378.

- Evensen S, Wisløff T, Lystad JU, et al. Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: a population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(2):476–483.

- Marwaha S, Johnson S, Bebbington P, et al. Rates and correlates of employment in people with schizophrenia in the UK, France and Germany. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:30–37.

- Silva-Junior JS, Fischer FM. Long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders is associated with individual features and psychosocial work conditions. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115885.

- Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:522–526.

- Mental Health Foundation. Out at work: a survey of the experiences of people with mental health problems within the work-place. London (UK): Mental Health Foundation; 2002.

- Reavley NJ, Jorm AF, Morgan AJ. Discrimination and positive treatment toward people with mental health problems in work-place and education settings: findings from an Australian National Survey. Stigma Health. 2017;2(4):254–265.

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, et al. The INDIGO Study Group. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):408–415.

- Link B. Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. Am Soc Rev. 1982;47(2):202–215.

- Corrigan P, Lundin R. Don’t call me nuts. Tinley Park (IL): Recovery Press; 2001.

- Tan BL. Profile of cognitive problems in schizophrenia and implications for vocational functioning. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(4):220–228.

- Ebuenyi ID, Guxens M, Ombati E, et al. Employability of persons with mental disability: understanding lived experiences in Kenya. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:539.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Economic Analysis. World economic situation and prospects. New York (NY): UN DESA; 2019. (Briefing, No. 125).

- International Labour Office. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2019. Geneva (Switzerland): ILO; 2019.

- Gregg P, Tominey E. The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Economics. 2005;12(4):487–509.

- International Labour Organisation. ILO Monitor: Covid-19 and the world of work. Fourth edition. Update estimates and analysis, May 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available online at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_749399.pdf

- Lijster JM, Dierckx B, Utens EM, et al. The age of onset of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(4):237–246.

- Dagani J, Signorini G, Nielssen O, et al. Meta-analysis of the interval between the onset and management of bipolar disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(4):247–258.

- Clark HB, Unruh D. Understanding and addressing the needs of transition-age youth and young adults and their families. In: Clark HB, Unruh DK, editors. Transition of youth and young adults with emotional or behavioral difficulties: an evidence-supported handbook. Baltimore (MD): Brookes Publishing; 2009. p. 3–22.

- Martin N, McKee K. Career services guide: supporting people affected by mental health problems. The Canadian Education and Research Institute for Counselling. Toronto, Ontario. 2015 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available online at https://cica.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Career_Services_Guide_WEB_May20_2015.pdf

- Korczak DJ, Goldstein BI. Childhood onset major depressive disorder: course of illness and psychiatric comorbidity in a community sample. J Pediatr. 2009;155(1):118–123.

- Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Hickie IB, et al. Early identification and intervention in depressive disorders: towards a clinical staging model. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(5):263–270.

- Ministry of Manpower, Singapore. Report: labour force in Singapore. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: https://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Labour-Force-In-Singapore-2019.aspx

- Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, et al. Mental disorders: employment and work productivity in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(1):117–123.

- Chua YC, Abdin E, Tang C, et al. First-episode psychosis and vocational outcomes: a predictive model. Schizophr Res. 2019;211:63–68.

- Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002.

- National Youth Council, Singapore. Youth Statistics in Brief 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available online at https://www.nyc.gov.sg/en/initiatives/resources/youth-statistics-in-brief/

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington (DC): Author; 2000.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 1998.

- Blank A, Harries P, Reynolds F. Mental health service users’ perspectives of work: a review of the literature. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74(4):191–199.

- Vaingankar JA, Cetty L, Subramaniam M, et al. Recovery in psychosis: perspectives of clients with first episode psychosis. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49(4):186–198.

- Koletsi M, Niersman A, van Busschbach JT, et al. Working with mental health problems: clients’ experiences of IPS, vocational rehabilitation and employment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(11):961–970.

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. Views and experiences of employment among people with psychosis: a qualitative descriptive study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005;51(4):302–316.

- Goffman E. Stigma: notes on a spoiled identity. New York (USA): Jenkins, JH & Carpenter; 1963.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Link BG. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:1–6.

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71(8):742–751.

- Toth KE, Dewa CS. Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):732–746.

- van Niekerk L. Identity construction and participation in work: learning from the experiences of persons with psychiatric disability. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23(2):107–114.

- Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Ribar D. The bilateral relationship between depressive symptoms and employment status. Bonn (Germany): IZA; 2017. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 10653).

- Harrington B, Van Deusen F, Fraone JS, et al. How millennials navigate their career: young adult views on work, life and success. Chestnut Hill (MA): Boston College Center for Work & Family; 2015.

- van Niekerk L. Participation in work: a source of wellness for people with psychiatric disability. Work. 2009;32(4):455–465.

- Wolfe A, Hall AC. The influence of families on the employment process. Tools for inclusion brief, Issue No. 24. Boston (MA): Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston; 2011.

- Rinaldi M, Killackey E, Smith J, et al. First episode psychosis and employment: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(2):148–162.

- OECD. Fit mind, fit job: from evidence to practice in mental health and work, mental health and work [Internet]. Paris (France): OECD Publishing; 2015 [cited 2020 July 30]. Available online at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264228283-en

- Britt E, Sawatzky R, Swibaker K. Motivational interviewing to promote employment. J Employ Couns. 2018;55(4):176–189.

- van Duin D, de Winter L, Oud M, et al. The effect of rehabilitation combined with cognitive remediation on functioning in persons with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(9):1414–1425.

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al. An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Serv. 1997;48:335–346.

- Malachowski C, Kirsh B. Workplace antistigma initiatives: a scoping study. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):694–702.

- Bratbo J, Vedelsby AK. One of us: the national campaign for anti-stigma in Denmark. In: Gaebel W, Rössler W, Sartorius N, editors. The stigma of mental illness – end of the story? Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 317–338.

- Tee Z. Mental health declaration for job applicants discriminatory. Strait Times [Internet]. 2020 Jan 20 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/mental-health-declaration-for-job-applicants-discriminatory

- Brouwers EP, Mathijssen J, Van Bortel T, et al. Discrimination in the workplace, reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study in 35 countries. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009961.

- Yoshimura Y, Bakolis I, Henderson C. Psychiatric diagnosis and other predictors of experienced and anticipated workplace discrimination and concealment of mental illness among mental health service users in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(10):1099–1109.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: the evidence for stigma change. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2016.