Abstract

Objective: To investigate and summarize the literature on the validation of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core sets from 2001 to 2019 and explore what research methods have been used when validating ICF core sets.

Methods: The current study is a scoping review using a structured literature search.

Results: In total, 66 scientific articles were included, of which 23 ICF core sets were validated. Most validation studies were conducted in Europe using a quantitative methodology and were validated from the perspective of patients. Analysis methods differed considerably between the studies, and most ICF core sets were validated only once for a single target population or from a single perspective. The comprehensive core sets were validated more often than the brief core sets, and core sets for stroke and low back pain were validated most often.

Conclusion: The results of the current study show that only 66% of the existing ICF core sets are validated. Many of the validation studies are conducted in a European context and from a single perspective. More validation studies of ICF core sets from the perspective of both patients and professionals are needed.

ICF core sets aim to facilitate assessments in clinical settings and research.

Validation studies indicate in general that the ICF core sets are valid and relevant for patients and professionals in the specific areas explored and thus can be used in rehabilitation settings.

To improve the quality of ICF core sets, more validation studies are needed for ICF core sets not yet tested and for ICF core sets that have been validated only in one study or for one specific population or target group.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001, and it is a classification and framework to describe health [Citation1]. The ICF model presents a multidimensional and biopsychosocial view of health () and can be used for all individuals regardless of their health condition or degree or cause. The classification is based on the individual in a specific context, where the interaction between all ICF parts is important. One of the aims of the ICF is to use numerical codes to serve as a common language for health professionals to describe the functioning of individuals with a health condition and thereby make the results of studies (using the ICF) comparable at national and international levels. The ICF may also be used in research studies, political decisions and within the field of education [Citation1], as it serves as a common language in these areas as well. The ICF consists of 1495 numerical codes arranged in a hierarchy consisting of three parts: body functions and body structures, activity and participation and contextual factors. Each part is divided into chapters (1st level), and then categories are arranged at different levels (2nd–4th levels). For each level, the category, which includes a definition of the content, becomes more specific [Citation1].

Figure 1. The ICF bio-psycho-social model of health [Citation1].

![Figure 1. The ICF bio-psycho-social model of health [Citation1].](/cms/asset/83a85b54-42f4-4d18-9b78-0536956c955e/idre_a_1878562_f0001_b.jpg)

Because of the great extent of ICF, so-called “core sets” have been developed. A core set is a shortlist of selected categories from the whole ICF, specified for a specific health condition (e.g., hearing loss), circumstance (e.g., pregnancy) or situation (e.g., vocational rehabilitation). There are two kinds of core sets: comprehensive core sets, consisting of all ICF categories relevant to the specific area, and brief core sets, which are more compressed versions of the comprehensive core sets [Citation2]. Until 2017, 35 core sets for different health conditions, circumstances, and situations, as well as generic core sets, have been developed [Citation3].

When developing ICF core sets, there are guidelines to follow () [Citation2]. The guidelines include a process of three steps, starting with four preparatory studies: (a) an empirical multicenter study to investigate which functional problems are most frequently experienced in a population with respect to a specific health condition, (b) a systematic literature review, (c) a qualitative study focusing on the people experiencing the specific health condition and (d) an experts’ survey [Citation2]. The results of preparatory studies are linked to ICF categories [Citation2], and in the next phase, the results are presented at a consensus conference. At the conference, the first version of a brief, comprehensive core set for the specific health condition is created. The final step, Phase II, is the validation of the first version of the core sets [Citation2]. For the validation phase, there are further guidelines, as described by Grill [Citation4].

Figure 2. The development process of the ICF core sets for hearing loss [Citation85].

![Figure 2. The development process of the ICF core sets for hearing loss [Citation85].](/cms/asset/737b123f-5f37-4b2f-af80-683153ba477c/idre_a_1878562_f0002_b.jpg)

Quality, in the form of validity, is important for all types of instruments that are intended to be used in both clinical settings and for research purposes. Therefore, when developing and evaluating an instrument, validation is one of the most fundamental issues [Citation5]. There are several kinds of validity, including content, construct and criterion validity. The domain validity can be defined as “the degree to which an outcome measure measures the construct it purports to measure” [Citation6]. Validation can also be described as “the process in which we gather and evaluate the evidence to support the appropriateness, meaningfulness, and usefulness of the decisions and inferences” [Citation7, p.9]. An ICF core set is not an instrument, but it can serve as the foundation for developing instruments for clinical settings and research. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the core set measures and captures what it is supposed to, in other words, that the core set has satisfying validity. To ensure the different aspects of the validity, it is possible to evaluate one or several kinds of validity (e.g., content-construct and criterion validity) and other psychometric aspects, such as reliability and responsiveness [Citation6].

When reading the literature about the validation of ICF core sets, it must be noted that the validation studies were conducted differently and with different methods and analyses and from different perspectives.

To date, four literature reviews have been conducted on ICF [Citation8–10] and ICF core sets [Citation11]. The literature reviews show that most ICF studies have been conducted in Europe or the United States, and almost no studies have been conducted in African countries [Citation9,Citation10]. The same trend can be identified for studies focusing on developing ICF core sets [Citation11]. In 2012, 166 studies described the development of ICF core sets for a total of 18 different health conditions, circumstances, or situations. According to Yen et al. [Citation11], the first ICF core set development study was published in 2001, but most studies were published in 2004–2005 and 2010–2012. The most common journals for publications were Disability and Rehabilitation, followed by the Journal of Rehabilitation and Medicine [Citation11].

The literature studies that have been conducted since 2001 have focused on ICF in general [Citation8–10] or the development of ICF core sets [Citation11], but thus far, no literature reviews are focusing on the validation of ICF core sets. An initial search of validation literature indicates that the recommended guidelines, described by Grill [Citation4], have been followed differently and that many different methods have been used in validation processes. Since validation is the final phase when developing ICF core sets [Citation2] and is an important part of developing new instruments [Citation5], a review study focusing on the validation of ICF core sets is needed. It will serve as a useful and important introduction to the topic when further studying and validating ICF core sets. Hence, this study aims to investigate and summarize the literature on validating ICF core sets from 2001 to 2019. The aim is further to explore what research methods have been used when validating ICF core sets.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The present study is a scoping review following the methodology described by Kahlil et al. [Citation12]. Relevant articles were identified by searches in 10 different scientific online databases: AMED, CINAHL, ERIC, PubMed, Scopus, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, SveMed+, PsycINFO and Web of Science. The search was conducted using both thesaurus and Boolean search methods, and the keywords used were ICF, International classification of functioning disability and health, Core set, Core sets, validation, validity, psychometric and psychometrics. Because ICF terms were endorsed in 2001, the search was limited to articles published between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2019. No other limits were used. A full search of the PubMed database is shown in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Since 2001, when the ICF core set project started, core sets within 35 different areas/health conditions have been developed (including conditions and settings such as neurological conditions and post-acute care) [Citation3]. When developing ICF core sets, there is a certain development process to follow [Citation2], and only core sets that had been developed according to these guidelines were included in the present review to narrow the data and increase the reliability. Furthermore, to narrow the extent of the literature review, only core sets for adults were included, and core sets for children and youth (ICF-CY) were excluded. Articles were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: they were published between January 2001 and December 2019, “ICF core set” was mentioned in the title or abstract, the language of the article was English and the article focus was psychometric testing, mainly a validation of an ICF core set. Articles focusing on reliability or other psychometric aspects were also included in the first stage.

Articles were excluded from the present study if they were (1) not original articles, for example, editorials, letters, commentary notes or conference papers, (2) published in languages other than English, (3) validation studies of ICF-CY or focusing on people aged ≤ 18 years and (4) not a validation of core sets as defined, for example, by validation of ICF in general or were instruments based on ICF core sets. The last exclusion criterion was set to limit the search and because it was hard to assess to what degree each instrument was based on ICF core sets (in total or in some parts) and thus should be included.

Data extraction and analysis

Two reviewers independently reviewed all abstracts. In the next step, both reviewers read the full text of all selected articles, and data were extracted based on a data entry sheet created for this study. The content of the data sheet was based on what is recommended for scoping reviews [Citation12–14], and the variables first author, publication year, place of origin, journal, kind of core set (e.g., comprehensive or brief), core set, study population, sample size, study method (e.g., quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods), analysis method (e.g., statistics, content analysis), and kind of validity examined were examined. The data extraction was performed with a focus on which core sets had been validated and which methods had been used. For analysis, descriptive statistics were used, and the frequency of the variables was calculated. The software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for analysis.

Results

Included studies

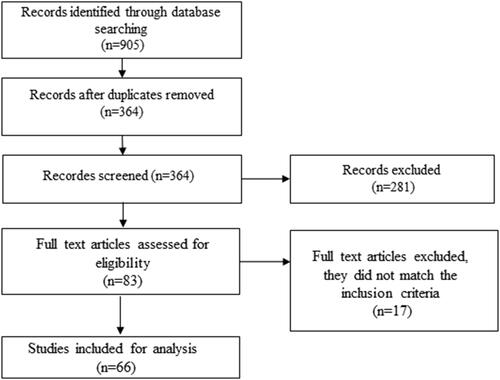

In total, 905 articles were identified in the initial database search. After removing duplicates and articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, 83 studies were included. The full text of these was read, and from these, 66 were included [Citation15–80]. The data collection process is described in .

Core sets

Twenty-three different core sets were validated, and those most examined included the ICF core sets for stroke and low back pain followed by osteoarthritis, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis (). The 23 core sets were validated in 66 studies, and three studies included validations of more than one core set. In a minority of the studies (n = 3), brief core sets were validated. The comprehensive ICF core set, or both comprehensive and brief core sets together, was validated in 63 studies.

Table 1. Number of validation studies.

Publications

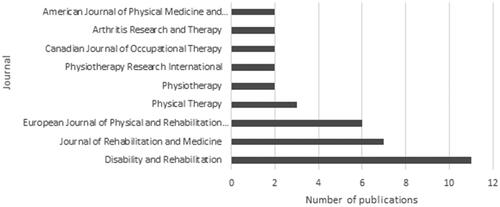

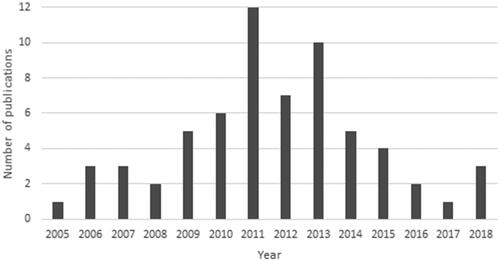

The ICF core set validation studies were published in 38 scientific journals; the nine journals with more than one publication are presented in . The scientific journal with the most frequent publication of ICF validation studies was Disability and Rehabilitation (29%). The second-most frequent journal was the Journal of Rehabilitation and Medicine (18%), followed by the European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (16%). The first validation study was published in 2005, and the last study included in the present study was published in 2019. Most studies were published between 2009 and 2015, with a peak in 2011, when 12 validation studies were published ().

Place of origin

There were 53 different people named as first authors in the studies, and the studies originated from 64 different countries (); the majority were from European countries (80%), where most originated in Germany and Switzerland. Only 11% of the studies were based in Asia, 5% in South America and Australia and 3% in North America. There were no ICF core set validation studies from Africa.

Table 2. Place of origin for the included studies, presented by continent and country.

Methods used in the validation studies

Most of the studies used a quantitative methodology (n = 50, 76%), while 13 used a qualitative methodology (20%) and three studies used a mixed methodology (5%). Most investigated the content validity (n = 59, 89%), and in six of these studies, both content and criterion validity were examined. A few studies investigated only criterion validity (n = 4, 6%) or construct validity (n = 3, 5%).

The analysis methods varied depending on methodology and the kind of validity examined. The most commonly used method of data collection was the Delphi method, followed by interviews and, finally, comparisons with questionnaires used in clinical settings and research using ICF linking as the analysis method. ICF linking means that meaningful units in health-related information are identified and linked to ICF according to the linking rules [Citation81]. For analysis, the most common methods were statistical methods such as descriptive statistics and modern test theory (n = 49, 74%), followed by qualitative analysis such as content analysis or thematic analysis (n = 13, 20%) and linking to other questionnaires (n = 4, 6%).

Validation study populations

Most of the validation studies identified in this study examined the validation of core sets from the perspective of patients and professionals (n = 64, 97%). Of these 64 studies, approximately one-third (n = 22, 34%) investigated validity from a professional/clinical perspective. In the group of professionals, seven different occupations were identified, most commonly physiotherapists (36%), followed by occupational therapists (18%) and physicians (18%). All study populations are shown in . Two studies (3%) compared the core sets with other instruments, so there were no study populations.

Table 3. Study populations of patients and professionals.

Discussion

Results

This scoping review explored the validation of ICF core sets. A total of 66 studies were included in the review, reporting validation processes for 23 different core sets. Most of the validation studies used quantitative methodology and investigated content validity. The perspective most validated was the patient perspective, followed by the professional perspective. The vast majority of the studies originated in Europe, and the studies were foremost published in rehabilitation journals.

Validation process and methods

When developing new instruments, it is important to examine psychometric properties such as validity and reliability [Citation5], and this also applies to ICF core sets. Therefore, the final step described in the development process of ICF core sets is validation and implementation [Citation2]. Considering this, it is noteworthy that only 66% of the core sets have been validated, even though it has been several years since the first versions of the core sets were developed. The validation phase is important in ensuring the validity of the core sets for the target group and in different cultural settings. Valid ICF core sets promote the robustness of instruments developed based on the ICF corset, and the questionable validity of core sets is a less than ideal foundation for an instrument. However, the use of validated instruments, in general, may be uncommon in clinical settings; for example, studies in the audiological field showed that many of the instruments used in audiological rehabilitation have not been validated, and there is a need for evidence-based instruments [Citation81,Citation82]. These examples from the audiological field can be assumed to be similar to and representative of other fields.

The results show that it is common to investigate the validity of the comprehensive core set alone or both the comprehensive and brief core sets together during the validation process. In only a few studies, the brief core set alone was validated. There is strength in validating both core sets simultaneously, since the items in the brief core set are included in the comprehensive core set. This means that all the included ICF categories are validated at the same time. On the other hand, the brevity of the brief core set makes it more useful in clinical settings and research, and because of this usefulness, it may be more relevant to validate only the brief ICF core sets to avoid using invalid versions of instruments.

In most validation studies, a quantitative methodology was used (76%), which is a common method in validation studies and is also recommended for the validation of ICF core sets [Citation4]. Other possible methods include different qualitative methods and mixed methods, which have also been used in ICF core set validation studies. The most common kind of validity examined in ICF core set validation studies is content validity, which is an elemental kind of validity [Citation5,Citation6], and only a few studies have investigated construct validity or criterion validity, which are also important aspects of validity [Citation5,Citation6]. Construct validity shows whether an instrument is unidimensional or if there are items that do not fit the model, while criterion validity compares the items with other instruments used in the same field to confirm whether they are relevant [Citation5]. These aspects were not captured in most ICF core set validation studies, which can be considered a shortcoming.

The choice of analysis methods in the validation studies varied considerably based on the methodological approach and the aim of the study. The most common analysis method in the studies was to follow the analysis methods described in Grill’s validation recommendations [Citation4] or to use the so-called Delphi survey method using statistical analysis. The Delphi methodology was commonly used for studies conducted in Germany and Switzerland.

For whom is the core set valid?

A question to be asked when exploring validation of the ICF core sets is for whom the core set is valid? The core sets that had been validated most often included the core sets for stroke, low back pain, osteoarthritis, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. These core sets were validated from the perspectives of different stakeholders, such as patients and rehabilitation professionals. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the functioning and health of individuals living with a specific health condition, validation of the corresponding core set from different perspectives is warranted. There were no validation studies identified for the core sets for vertigo, sleep, inflammatory bowel diseases, ankylosing spondylitis, osteoporosis, traumatic brain injury, bipolar disorders and depression. However, most of these health conditions are highly relevant with respect to rehabilitation interventions and call for validation if they are to be used in clinical rehabilitation practice.

The study populations consisted mostly of patients with specific health conditions (based on the core set investigated) or professionals working in the specific field. Within the group of professionals, validation was common with occupations working within rehabilitation settings, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists and speech therapists as well as physicians and nurses. These findings support the fact that ICF is applied within the rehabilitation field and is used for target groups and organizations where it is to be practiced [Citation1]. However, depending on which profession was involved in the validation, the perspectives may differ. For example, the profession most frequently involved in the validation process is physiotherapy, which focuses on certain aspects of rehabilitation, which is within the scope of the profession. Other professions focus on other aspects of the same health condition. To make a multidimensional instrument as valid as possible, different perspectives are needed for the same core set. Thus, even if a core set is validated from one professional perspective, adding other perspectives will further increase the validity. A similar argument can be made for the patient perspective in the validation process, and combined validation from both the patient and professional perspectives may be preferable to obtain theoretical, clinical and individual perspectives.

From a diversity perspective, most validation studies included both sexes, even though there was a slight tendency for women to be overrepresented. This could be because some health conditions, such as breast cancer, were investigated specifically in women [Citation37,Citation83]. Age is another variable to consider in validation studies; these studies focused mainly on adults in general, with a mean approximate age of 60 years. Only a few studies have focused on a specific age group, “older adults” [Citation72]. The ICF categories in each core set may be of different importance for different age groups, which could be identified in the validation process. The level of education was rarely described in validation studies, and in the few studies where it was examined, the terminology used differed. Hence, validity for a diverse population is less explored, meaning that diversity is an important factor to include in future validation studies.

One fact of note in this scoping review (), as in previous ICF review studies, is that most of the studies were conducted in Europe or the United States. This applies to ICF studies in general [Citation8–10] and studies focusing on the ICF development process [Citation11]. Of the validation studies, 80% were conducted in Europe, and only a few were conducted in the United States. Most ICF development studies were conducted in Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, where the ICF research branch is located [Citation84]. The current study also noted that no core sets have been validated in African countries. This finding is expected, as few other ICF core set studies have taken place in this region [Citation11]. Additionally, this lack of cultural diversity is a disappointing finding, as ICF core sets need to be valid in all cultural contexts, including high- and low-income countries; this is also recommended when validating new instruments in general [Citation5]. Previous ICF review studies have highlighted the “information paradox” identified by the WHO, meaning that there are information gaps for countries with a high health burden [Citation9]. This seems to be confirmed with respect to ICF validation studies as well.

Table 4. Protocol for the current scoping review.

The quality and the results of validation studies were not analyzed in the current study, but when reading through, the results indicated in general that core sets are valid and thus relevant for patients and professionals in the specific area explored.

Publications

In total, 66 published validation studies were included in this review. Most of these studies were published in scientific journals, focusing on rehabilitation and medicine, which is in line with the fields where ICF is practiced [Citation1] and with previous review studies of ICF [Citation9–11]. The first ICF validation study was published in 2005, four years after the classification was introduced and the first core sets were initiated [Citation9–11]. Validation studies have been published at a similar pace, with a few years of delay after the specific ICF core sets were developed. This time frame is reasonable, considering that the development of core sets is an extensive process including several research studies and a consensus conference [Citation2].

Strengths and limitations

It is important to acknowledge that the scoping review methodology contains both strengths and limitations. For the search strategy, guidelines from the Örebro University library were used to identify relevant databases and the keywords most appropriate for the study area. This is considered a strength, as the quality of a study is dependent on identifying relevant articles. However, it is possible that some relevant publications were not included due to the choice of search strategies and keywords, even though the choices were made in line with established guidelines for literature reviews.

In the literature search, concepts related to validity (e.g., psychometrics and reliability) were included. This resulted in a more extensive number of articles to read and assess, but it decreased the risk of excluding relevant articles. The inclusion criteria required that ICF core sets be developed according to the recommendations, so studies involving the development of core sets using another methodology were excluded. For this reason, it is possible that some relevant publications were not included.

A limitation of this scoping review is that it does not include studies examining the validation of instruments that have been developed from ICF core sets. These studies were excluded because it was difficult to assess the extent to which the instruments were developed on the basis of ICF core sets, whether it was based on the core set in full or only on certain parts.

In line with the scoping review methodology, the quality of the articles included was not assessed [Citation12]. This could make it hard to identify research gaps due to poor quality. However, by not addressing quality appraisal issues, this study potentially includes a great range of study designs and empirical methods, which is a strength. However, it was noted during the selection process that the quality differed among the included studies, which makes it relevant to include this aspect in future review studies.

Conclusion

The results show that additional validation studies are needed, especially from the perspectives of different stakeholders with different characteristics, such as patients of different ages and professionals from diverse disciplines. This fact indicates that the validation of ICF core sets in general has just begun, and more validation studies are needed, both for the core sets not yet tested and for the core sets only validated in one study or for one population or target group.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declaration of interest.

References

- World health organization, International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). 2001. Geneva: WHO.

- Selb M, Escorpizo R, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, et al. A guide on how to develop an international classification of functioning, disability and health core set. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(1):105–117.

- Stucki G, Prodinger B, Bickenbach J. Four steps to follow when documenting functioning with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(1):144–149.

- Grill E, Stucki G. Criteria for validating comprehensive ICF Core Sets and developing brief ICF Core Set versions. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(2):87–91.

- Machin D, Fayers PM. Quality of life: the assessment, analysis, and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. 2. rev. ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2007.

- COSMIN. COSMIN taxonomy of measurement properties. 2020. Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/cosmin-taxonomy-measurement-properties/

- Chan K. Standards and guidelines for validation practices: development and evaluation of measurement instruments. In: Zumbo B, Chan E, editors. Validity and validation in social, behavioral, and health sciences.New York: Springer Publishing; 2014. p. 9–24.

- Madden RH, Bundy A. The ICF has made a difference to functioning and disability measurement and statistics. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(12):1450–1462.

- Jelsma J. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a literature survey. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(1):1–12.

- Cerniauskaite M, Quintas R, Boldt C, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2009: its use, implementation and operationalisation. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(4):281–309.

- Yen T-H, Liou T-H, Chang K-H, et al. Systematic review of ICF core set from 2001 to 2012. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(3):177–184.

- Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, et al. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(2):118–123.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146.

- Abdullah MF, Nor NM, Mohd Ali SZ, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core sets for diabetes mellitus: a Malaysian perspective. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2011;40(4):168–178.

- Aiachini B, Cremascoli S, Escorpizo R, et al. Validation of the ICF Core Set for Vocational Rehabilitation from the perspective of patients with spinal cord injury using focus groups. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(4):337–345.

- Alfakir R, Holmes AE, Noreen F. Functional performance in older adults with hearing loss: Application of the International Classification of Functioning brief core set for hearing loss: A pilot study. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(9):579–586.

- Algurén B, Bostan C, Christensson L, et al. A multidisciplinary cross-cultural measurement of functioning after stroke: Rasch analysis of the brief ICF Core Set for stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(Suppl 1):573–586.

- Alguren B, Lundgren-Nilsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Functioning of stroke survivors–A validation of the ICF core set for stroke in Sweden. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):551–559.

- Awad H, Alghadir A. Validation of the comprehensive international classification of functioning, disability and health core set for diabetes mellitus: physical therapists' perspectives. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(11):968–979.

- Bagraith KS, Hayes J, Strong J. Mapping patient goals to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): examining the content validity of the low back pain core sets. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(5):481–487.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) can be used to describe multidisciplinary clinical assessments of people with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(3):383–389.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. Self-reported disability according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Low Back Pain Core Set: Test-retest agreement and reliability. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(4):621–626.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. What do clinicians consider when assessing chronic low back pain? A content analysis of multidisciplinary pain centre team assessments of functioning, disability, and health. Pain. 2018;159(10):2128–2136.

- Bautz-Holter E, Sveen U, Cieza A, et al. Does the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for low back pain cover the patients' problems? A cross-sectional content-validity study with a Norwegian population. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(4):387–397.

- Becker S, Kirchberger I, Cieza A, et al. Content validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Head and Neck Cancer (HNC): the perspective of psychologists. Psychooncology. 2010;19(6):594–605.

- Berno S, Coenen M, Leib A, et al. Validation of the Comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Core Set for multiple sclerosis from the perspective of physicians. J Neurol. 2012;259(8):1713–1726.

- Bos I, Stallinga HA, Middel B, et al. Validation of the ICF core set for neuromuscular diseases. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49(2):179–187.

- Bossmann T, Kirchberger I, Glaessel A, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for osteoarthritis: the perspective of physical therapists. Physiotherapy. 2011;97(1):3–16.

- Coenen M, Cieza A, Stamm TA, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for rheumatoid arthritis from the patient perspective using focus groups. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R84.

- Conrad A, Coenen M, Schmalz H, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for multiple sclerosis from the perspective of occupational therapists. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(6):468–487.

- Conrad A, Coenen M, Schmalz H, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for multiple sclerosis from the perspective of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2012;92(6):799–820.

- Cooney M, Galvin R, Connolly E, et al. The International Classification of Functioning (ICF) core set for breast cancer from the perspective of women with the condition. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(9):740–748.

- Ewert T, Allen DD, Wilson M, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health framework using multidimensional item response modeling. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(17):1397–1405.

- Gebhardt C, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF Core Set for rheumatoid arthritis: the perspective of physicians. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(8):780–788.

- Glaessel A, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, et al. Does the Comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for Breast Cancer capture the problems in functioning treated by physiotherapists in women with breast cancer? Physiotherapy. 2011;97(1):33–46.

- Glassel A, Coenen M, Kollerits B, et al. Content validation of the international classification of functioning, disability and health core set for stroke from gender perspective using a qualitative approach. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;50(3):285–299.

- Glässel A, Coenen M, Kollerits B, et al. Validation of the extended ICF core set for stroke from the patient perspective using focus groups. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(2):157–166.

- Glässel A, Kirchberger I, Kollerits B, et al. Content validity of the extended ICF core set for stroke: An International Delphi Survey of Physical Therapists. Phys Ther. 2011;91(8):1211–1222.

- Grill E, Grimby G, Stucki G. The testing and validation of the ICF core sets for the acute hospital and post-acute rehabilitation facilities - towards brief versions. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(2):81–180.

- Grill E, Stucki G, Scheuringer M, et al. Validation of International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Core Sets for early postacute rehabilitation facilities: comparisons with three other functional measures. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(8):640–649.

- Guo T, Chen X. Reliability and validity of the brief ICF Core Sets for Chinese stroke patients. Chinese J Rehabilit Med. 2008;23(8):700–703.

- Herrmann KH, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, et al. The comprehensive ICF core sets for spinal cord injury from the perspective of occupational therapists: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(5):600–613.

- Hieblinger R, Coenen M, Stucki G, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for chronic widespread pain from the perspective of fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R67

- Hilfiker R, Obrist S, Christen G, et al. The use of the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for low back pain in clinical practice: a reliability study. Physiother Res Int. 2009;14(3):147–166.

- Jobst A, Kirchberger I, Cieza A, et al. Content validity of the comprehensive ICF core set for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases: An International Delphi Survey. Open Respir Med J. 2013;7:33–45.

- Karhula ME, Kanelisto KJ, Ruutiainen J, et al. The activities and participation categories of the ICF Core Sets for multiple sclerosis from the patient perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(6):492–497.

- Kinoshita S, Abo M, Miyamura K, et al. Validation of the “Activity and participation” component of ICF Core Sets for stroke patients in Japanese rehabilitation wards. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(9):764–768.

- Kirchberger I, Coenen M, Hierl FX, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for diabetes mellitus from the patient perspective using focus groups. Diabet Med. 2009;26(7):700–707.

- Kirchberger I, Stamm T, Cieza A, et al. Does the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for rheumatoid arthritis capture occupational therapy practice? A content-validity study. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74:267–280.

- Kirschneck M, Kirchberger I, Amann E, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for low back pain: the perspective of physical therapists. Man Ther. 2011;16(4):364–372.

- Kurtaiş Y, Őztuna D, Genç A, et al. Reliability, construct validity and measurement potential of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Comprehensive Core Set for Chronic Widespread Pain. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 2013;21(3):231–243.

- Kus S, Dereskewitz C, Wickert M, et al. Validation of the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for hand conditions. Hand Therapy. 2011;16(3):58–66.

- Köseoǧlu BF, Murphy MA, Lundgren-Nilsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for stroke in Turkish stroke patients. Turk Geriatri Dergisi. 2013;16(1):8–19.

- Lage SM, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for obstructive pulmonary diseases in the perspective of adults with asthma. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;42(1):86–92.

- Leib A, Cieza A, Tschiesner U. Perspective of physicians within a multidisciplinary team: content validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34(7):956–966.

- Lemberg I, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, et al. The ICF Core Set for stroke from the perspective of physicians: a worldwide validation study using the Delphi technique. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46(3):377–388.

- Lygren H, Strand LI, Anderson B, et al. Do ICF core sets for low back pain include patients' self-reported activity limitations because of back problems? Physiother Res Int. 2014;19(2):99–107.

- Marques A, Jácome C, Gabriel R, et al. Comprehensive ICF core set for obstructive pulmonary diseases: validation of the activities and participation component through the patient's perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(20):1686–1691.

- Marques A, Jacome C, Goncalves A, et al. Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for obstructive pulmonary diseases from the patient's perspective. Int J Rehabil Res. 2014;37(2):152–158.

- Moll VMK, Escorpizo R, Bergamaschi RP, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF Core Set for vocational rehabilitation from the perspective of physical therapists: International Delphi Survey. Physical Therapy. 2016;96(8):1262–1275.

- Müller M, Grill E, Stier-Jarmer M, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF Core Sets for patients receiving rehabilitation interventions in the acute care setting. J Rehabilit Med. 2011;43(2):92–101.

- Nuno L, Barrios M, Rojo E, et al. Validation of the ICF Core Sets for schizophrenia from the perspective of psychiatrists: an international Delphi study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:134–141.

- Oberhauser C, Escorpizo R, Boonen A, et al. Statistical validation of the brief International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for osteoarthritis based on a large international sample of patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(2):177–186.

- Paanalahti M, Alt Murphy M, Lundgren-Nilsson Å, et al. Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Stroke by exploring the patient's perspective on functioning in everyday life: a qualitative study. Int J Rehabil Res. 2014;37(4):302–310.

- Ptyushkin P, Selb M, Cieza A. ICF core sets: Manual for clinical practice. In: J. Bickenbach, A. Cieza, A. Rauch, & G. Stucki, editors. Hogrefe publishing: Göttingen; 2012. p. 14–21.

- Rauch A, Kirchberger I, Boldt C, et al. Does the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for rheumatoid arthritis capture nursing practice? A Delphi survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1320–1334.

- Rauch A, Kirchberger I, Stucki G, et al. Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for obstructive pulmonary diseases from the perspective of physiotherapists. Physiother Res Int. 2009;14(4):242–259.

- Renom M, Conrad A, Bascuñana H, et al. Content validity of the comprehensive ICF Core Set for multiple sclerosis from the perspective of speech and language therapists. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(6):672–686.

- Riberto M, Lopes KAT, Chiappetta LM, et al. The use of the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core set for stroke for chronic outpatients in three Brazilian rehabilitation facilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(5):367–374.

- Røe C, Sveen U, Cieza A, et al. Validation of the Brief ICF core set for low back pain from the Norwegian perspective. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(3):403–414.

- Spoorenberg SLW, Reijneveld SA, Middel B, et al. The Geriatric ICF Core Set reflecting health-related problems in community-living older adults aged 75 years and older without dementia: development and validation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(25):2337–2343.

- Stamm TA, Cieza A, Coenen M, et al. Validating the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Comprehensive Core Set for Rheumatoid Arthritis from the patient perspective: a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(3):431–439.

- Stier-Jarmer M, Grill E, Müller M, et al. Validation of the comprehensive ICF Core Set for patients in geriatric post-acute rehabilitation facilities. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(2):102–112.

- Tschiesner U, et al. Content validation of the international classification of functioning, disability and health core sets for head and neck cancer: a multicentre study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(6):674–687.

- Wang P, Li H, Guo Y, et al. The feasibility and validity of the comprehensive ICF core set for stroke in Chinese clinical settings. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(2):159–171.

- Weigl M, Wild H. European validation of The Comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set for Osteoarthritis from the perspective of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(26):3104–3112.

- Xie F, Lo NN, Lee HP, et al. Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Osteoarthritis (OA) in patients with knee OA: a Singaporean perspective. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(11):2301–2307.

- Xie F, Lo NN, Lee HP, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Brief Core Set for osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(6):450–461.

- Xie F, Thumboo J, Fong K-Y, et al. Are they relevant? A critical evaluation of the international classification of functioning, disability, and health core sets for osteoarthritis from the perspective of patients with knee osteoarthritis in Singapore. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(8):1067–1073.

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):212–218.

- Manchaiah V, Granberg S, Grover V, et al. Content validity and readability of patient-reported questionnaire instruments of hearing disability. Int J Audiol. 2019;58(9):565–575.

- Khan F, Amatya B, Ng L, et al. Relevance and completeness of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) comprehensive breast cancer core set: the patient perspective in an Australian community cohort. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(7):570–580.

- ICF Research Branch. History. 2017. Available from: https://www.ic.f-research-branch.org/about-us/history

- Danermark B, Granberg S, Kramer SE, et al. The creation of a comprehensive and a brief core set for hearing loss using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Am J Audiol. 2013;22(2):323–328.

Appendix 1

Full electronic search strategy for the database pubmed 12 february 2019

Search information

The search was made 12 February 2019. In total, this search resulted in 176 articles. A final complementary search were mare 2 December 2019 to include articles from 2019.

Limitations

Articles published between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2018.

Search strategy for ICF core sets

#1 ICF

#2 International classification of functioning disability and health

#3 Core set

#4 Core sets

Search strategy for validation

#5 validation

#6 validity

#7 psychometric

#8 psychometrics

Search strategy for all

#9. ((#1) OR (#2) OR (#3) OR (#4))

#10 ((#5) OR (#6) OR (#7) OR (#8))

#11 ((#9) AND (#10))