Abstract

Purpose

Stroke survivors receive considerable rehabilitation efforts as inpatients, but one-on-one therapy decreases after discharge. The gap between the amount of required therapy and the lack of its availability in this phase of care may be partly overcome by self-practice. However, patient's adherence to prescribed programs is often low. While single studies have examined factors affecting adherence in this specific case, they have not been reviewed and synthesised previously.

Methods

A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies explored factors affecting stroke survivors’ adherence to prescribed, recovery-oriented self-practice. Five databases were systematically searched for references: Medline, Psycinfo, CINAHL, Embase, and ASSIA. Quality assessment was undertaken using the CASP tool.

Results

From 1308 references, 68 potential papers were read in full, and 12 were included in the review. An overarching theme was identified as: “Tailoring and personalization rather than standardization.” It was informed by the following three analytical themes: “The meaning of ‘self’ in self-practice,” “Identifying self-practice as a team effort,” and “Self-practice that is grounded in one’s reality.”

Conclusion

To have a positive effect on adherence to self-practice, clinicians are advised to spend time learning about each individual’s life circumstances, so they can tailor proposed exercise programs to patients’ personal situations, preferences, and needs.

The topic of patient’s adherence to self-practice of prescribed exercise is a common concern, often voiced by frustrated rehabilitation health professionals. Bridging the gap between the patient’s needs for post-discharge intensive therapy and the inability of healthcare systems to provide it could be filled partly by self-practice.

Adherence to self-practice has become even more essential since the COVID 19 pandemic and the decrease in face-to-face delivery of rehabilitation due to social distancing requirements.

Adherence to exercise is a broad topic. Reasons for poor adherence differ between patient populations and the exercises they are prescribed. This study focuses on post-discharge stroke survivors’ adherence to recovery targeted exercise that could be described as repetitive and less physically demanding movements and functions.

Reviewed studies were qualitative and usually included a relatively small number of participants within a specific context. Using thematic synthesis, we combined these small pieces of the puzzle into a larger picture, to produce recommendations that could be drawn on by clinicians to improve self-practice adherence.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability [Citation1]. The prevalence of stroke incidents in the United States between 2013 and 2016 was 2.5%, i.e., every 40 s, on average, one American has a stroke, and every three and a half minutes someone dies from a stroke [Citation2]. According to an older UK study, the incidence of stroke per 1000 people ranges from 1.33 to 1.58; direct and indirect annual costs of stroke were estimated at ∼9 billion pounds [Citation3].

Reductions in participation and activity levels due to stroke derive from a variety of impairments including a decrease in movement, sensation, cognitive abilities, verbal deficits, and its psychological impact. In work produced by Hall et al., it was found that only 15% of stroke survivors recover entirely, while the rest live with some level of impairment [Citation4].

Stroke rehabilitation efforts in developed countries are usually focused on the time spent at inpatient institutes [Citation5]. Studies conducted in European countries, such as the UK and Sweden, have reported a stay of between 30 and 85 days at inpatients rehabilitation units [Citation6]. Observational studies have shown that the average time of daily active therapy in some inpatient institutes is only 37 min [Citation7].

Further services include post-discharge outpatient therapy sessions, which are reported to decrease in frequency over time [Citation8]. No studies have been found on the precise length of community-based rehabilitation programs. However, indications are that most relevant trials stop one year after the stroke [Citation6].

The transition between the well-constructed inpatient stay to the community is often accompanied by diverse patient experiences [Citation9,Citation10]. Some patients feel they “walked away without any sort of feeling of continuity of resources available” [Citation9], and that healthcare professionals “should have been around also following discharge” [Citation11].

While therapy efforts decrease in their intensiveness up until complete cessation throughout the first year, patients in this phase still express their desire to maintain practice opportunities to “keep the door open for recovery” [Citation12]. A review conducted in 2014 provides evidence that more practice of the desired movement or function will lead to better recovery results [Citation13]. The number of repetitions required to impact brain plasticity, and by that to improve function, varies across trials but ranges between 300 and 800 repetitions per practice [Citation14]. Unfortunately, field studies report only 40 repetitions per session for either lower or upper extremities in both inpatient and outpatient settings [Citation15].

This gap between the vast amount of required therapy and the lack of its availability in more chronic, post-discharge phases of care can be partly filled by self-practice (or privately paid for care). During the current COVID pandemic, self-practice among stroke survivors has been even more essential as face-to-face delivery of rehabilitation is limited due to social distancing requirements. The term “self-practice” is related to practice that is done by patients themselves or with the help of their caregiver/non-professional therapist.

Self-practice is a well-established intervention that allows patients with different diagnoses to take an active part in their healing and to accept responsibility for their own progress; in addition, it saves costs for the healthcare system while providing significant results [Citation16,Citation17]. The major challenge to the success of self-practice lies in patient adherence.

Poor adherence to prescribed self-exercise has been reported by healthcare professionals about people with different diagnoses including stroke, from different cultures, and of different ages [Citation18,Citation19]. However, the reason for poor adherence may vary significantly between diagnoses. For example, parents and guardians of children with cerebral palsy, patients with Parkinson’s disease, and patients with Alzheimer's disease all reported different reasons for non-adherence to self-practice [Citation20–22]. It is therefore understood that clinicians cannot assume the existence of a fixed set of influencing factors for adherence to self-practice when prescribing self-practice to different patient populations. Even within the population of stroke survivors, factors that affect adherence to self-practice targeting secondary prevention (mostly aerobic and cardiovascular exercises that target general health and the prevention of a possible second stroke) may differ from factors that affect adherence to recovery-oriented exercise (mostly exercises of motor control to promote functional participation) [Citation23,Citation24]. As the exercises are different in nature, patients may be adherent to them for different reasons.

While levels of adherence may be measured quantitatively, the reasons behind the numerical values require an evaluation that is more qualitative [Citation25]. Qualitative research “is an ideal approach to elucidate how a multitude of factors, such as individual experience, peer influence, culture, or belief interact to form people’s perspectives and guide their behaviour” [Citation25].

Previous qualitative reviews have discussed adherence of stroke survivors to inpatient physical rehabilitation [Citation26], and well-being targeted interventions [Citation27]. To understand the adherence of these patients to recovery-oriented self-practice outside of clinical settings, to help support clinicians when recommending this type of activity to patients, qualitative research on this topic was collected and synthesised systematically.

Materials and methods

This review aimed to systematically collect, appraise and synthesise existing qualitative literature about the factors affecting stroke survivors adherence to recovery-targeted prescribed self-practice.

A thematic synthesis of qualitative papers was undertaken following a systematic literature search. Guidelines and criteria of the ENTREQ statement (Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research) were followed [Citation28]. The protocol for this thematic synthesis was registered through the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). It was published on 28 April 2020 (ID CRD42020163752).

Inclusion criteria

Papers that used a qualitative approach both for data collection and analysis. Mixed methods papers were included if containing a separate and defined qualitative part.

Papers that targeted the post-stroke adult population, over 18 years of age.

Papers exploring patients’ adherence to exercise programs as the main or secondary research topic.

Practice at the patient’s home or in another informal practice setting.

Exercise programs are prescribed but not delivered by healthcare professionals.

Only papers exploring exercise programs aiming for recovery of primary impairments or functional activities were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that were not published in peer-reviewed journals.

Studies examining brain damage/stroke populations afflicted at birth or as a result of developmental conditions.

Studies reflecting the direct views/perspectives of individuals other than patients (i.e., healthcare professionals, caregivers, and informal therapists). Papers that combined input from patients and other individuals were included if patients’ input was presented separately in the results/discussion section.

Studies involving exercise programs that were not oriented towards recovery from the diagnosed stroke.

Search strategy

A scoping search was undertaken to develop and conduct a more formal and systematic search on the following databases: Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase, and ASSIA. These databases were chosen as together they cover a range of disciplines and journals (medical, paramedical, nursing, social, psychological). An initial search was conducted in March 2020. It sought to find relevant references listed on these databases from their inception until March 2020. An updated search was undertaken in May 2021 to identify additional potential papers published after March 2020. The terms and combinations that we used were “exercise” or “physiotherapy” or “occupational therapy” or “speech” and “stroke” or “CVA” or “cerebrovascular accident” or “hemiplegia” and “qualitative” or “focus-group” or “interview.” Searches were limited to papers published or translated to English. We did not intentionally search for unpublished data (grey literature). However, when conference abstracts or other forms of unpublished data were found on a database, an effort was made through contacting their authors to find a published paper.

After removing duplications using RefWorks (a reference management software), the first reviewer (D.V.) screened all of the search results (hits) for inclusion based on their title/abstract according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A second reviewer (K.P.) screened 25% of the same hits to compare these results to those of the first reviewer. Discrepancies among reviewers were discussed to reach a decision. In addition, reference lists of the included studies were screened for more potential studies by both reviewers. Furthermore, three clinician peers involved in research relating to rehabilitation were asked to forward any suggestions, from their own knowledge of the topic, of papers that might be relevant. No additional included papers were located this way. When a full text could not be located online, its corresponding author was contacted through e-mail in an attempt to secure a copy of the full text.

Quality appraisal

Two independent reviewers (D.V. and K.P.) evaluated the quality of included papers, using the CASP checklist tool for qualitative studies (Critical Appraisal Skills Program 2017). It is often used to ensure that methodological rigor and ethical standards have been met in papers included in a thematic synthesis. The CASP tool appraises the study’s results and their applicability to other populations, contexts, and a specific research question.

The first reviewer (D.V.) reviewed and assessed all studies while the second reviewer (K.P.) only assessed two studies as it seemed that there was a good level of agreement between the reviewers regarding the quality of the components in the assessed studies. Hence, it was felt that the first reviewer was appropriately using the tool to be able to continue appraising papers alone.

Balancing the need for quality assurance of the included literature with the constant debate about whether or not to appraise qualitative studies [Citation29], we decided not to exclude any paper based on the quality appraisal but rather used the appraisal for the purpose of transparency and rigour.

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis was used, following the approach outlined by Thomas and Harden [Citation30]. The rationale for choosing this approach was: (a) clear phases are associated with it, and (b) to allow the findings to evolve beyond simple data summation. Using this approach, the authors were able to develop a clinically useful conceptual framework that applies to practice; it is based on the drawing together of data from across several papers to produce something, that is, more than the sum of its individual parts.

Each phase was undertaken by the first reviewer (D.V.) and then discussed with two other researchers (S.T. and A.T). The synthesis process involved an initial line-by-line coding of each segment of the data in all included papers. These segments often included information about the context, a patient’s quote, and the authors’ interpretation of data. Each segment was inductively coded according to its content and meaning. New codes were developed to represent new concepts until all of the segments from all of the studies had been coded. Codes that were either identical or close in meaning were clustered together into more general groups until they were narrowed down to form descriptive themes. Data from the results and the discussion sections of included papers were used in the synthesis. To stay true to the raw data, the data segments under each code were collected in a table, which was constantly checked and referred to whilst clustering and converting codes into descriptive themes. A final step in the analysis involved the interpretation of the descriptive themes to develop analytical themes. This allowed us to produce a conceptual framework that related to the review’s aim. Analytical themes move away from simply describing the data; they bring together data from different studies to create new conceptualisations and explanations. The analytical themes helped us to produce recommendations for clinicians on increasing patients’ adherence to their home prescribed exercises. The entire synthesis process was conducted manually, without the use of any computer software; this was possible because only a small number of papers were included. The coding table () provides an overview of how the analysis moved from the codes to descriptive themes and then to the final analytical themes.

Table 1. An illustration of the qualitative synthesis: analytical themes, descriptive themes, codes, and illustrative quotations.

Results

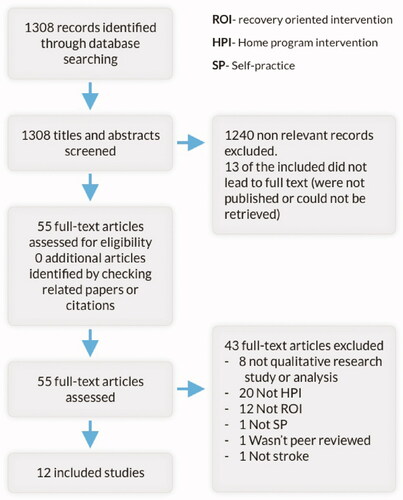

Following the removal of duplications, the initial search yielded 1308 hits. After screening all titles/abstracts for inclusion, 68 papers were identified to retrieve in full for reading. However, 13 of them could not be located. Efforts to locate them as full texts included an extensive search through the web, help from peers and librarians, and contacting the authors. Of the 55 full papers that were retrieved, read, and considered, 43 were excluded: most of these did not describe a qualitative approach, and the rest described cases of patients exercising together with healthcare professionals or with professional trainers in a formal setting. Twelve papers from the initial search were finally included in this review (see ). The updated search conducted in May 2021 located two additional relevant papers [Citation31,Citation32], which supported what had been identified already as themes (from papers from the initial search) but did not change these; therefore, they were not added to the overall review.

Characteristics of included studies

The twelve included papers used for the synthesis were all published after 2002. They were based on data from a total of 108 post-stroke patients. All of them used semi-structured interviews as the source of data collection, while three studies included additional focus groups. Most of the studies analyzed the data thematically (n = 7). The rest used content analysis (n = 2), grounded theory (n = 1), phenomenological analysis (n = 1); one study did not provide information regarding data analysis. The studies were conducted in nine different countries: USA (n = 4); Europe (n = 5 – Germany, UK, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden); Singapore (n = 1); India (n = 1); Australia (n = 1). Data from the Swedish study were collected in Uganda. For more information, please see the characteristics of included studies table ().

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Quality appraisal

Results from using the CASP tool are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1. The key reason for papers losing marks was a failure to mention the nature of the relationship between researcher and participants (n = 6 when the relationship was not discussed). In addition, the appropriateness of the data collection approach used was unclear in five of the studies. One study failed to reflect many of the components of the CASP tool [Citation33]. Despite the flaws, its findings were taken into consideration as they still provided valuable insights. Collecting qualitative data for synthesis is in essence a search for a variety of thoughts and experiences. It is better to use each found quote or segment than not to use it, as it may add to this variety. That is also the reason for the related protocol decision to not exclude studies based on their quality appraisal.

Data synthesis

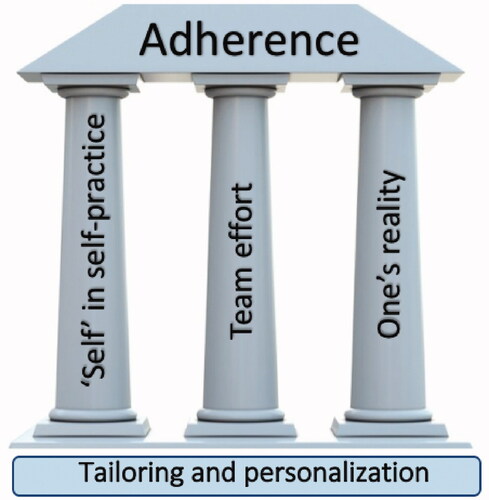

The phrase “self-practice” may initially be understood as a practice carried out independently by a patient. However, the extraction and analysis of data from the twelve included studies revealed a much wider perspective. This perspective is presented here through three analytical themes: “the meaning of ‘self’ in self-practice;” “identifying self-practice as a team effort;” and “self-practice grounded in one’s reality.” The development of these analytical themes resulted in discussions, as a team, about their meaning for clinical practice. This led to the production of an overarching theme that we labelled as “tailoring and personalization rather than standardization.” It demonstrates how each theme acts and interacts with patients’ individual needs and personal circumstances. It serves as the basis for the recommendations that are drawn from this review. This overarching theme is described in more detail below; we present the analytical themes first of all because they form the foundations for the overarching theme, as illustrated in a model displayed in that brings together these various elements of our findings. summarizes the main themes from the review.

Table 3. Table of themes.

Analytical theme 1: the meaning of “self” in self-practice

This analytical theme integrates elements that are a reflection of individual character traits, personal experiences and motivation, and worldviews. It expresses how adherence is driven by patients’ past experience and associated with their trust in healthcare professionals, their belief in the power of exercise in their recovery, their self-efficacy and ability to make amendments and respond to setbacks, and their perceived degree of interest in the training program.

Previous negative encounters within the healthcare system may affect an individual’s trust in activities suggested by other professionals, which may, in turn, lead to poor adherence or a search for alternative support:

“I haven’t seen one-on-one attention [in therapy] since I had my stroke… I can’t help but feel it is about money instead of people” [Citation34].

Some patients only carried out activities prescribed by professionals who they trusted and with whom they had a good rapport. They described some therapists as “useless,” while still believing that “access to suitably skilled therapy services could help them get going with exercise” [Citation12]. When patients lose their trust in healthcare, they may turn away from the system as a whole and seek different solutions, such as “alternative medicine” or “herbal oils,” based on a relative’s recommendations [Citation24].

High self-efficacy appeared to be an important factor in determining the conduct of self-practice but did not necessarily mean high adherence to prescribed exercises. Next to patients who were fully adherent to what was prescribed, others took responsibility to the next level by adapting and even reinventing their exercise program [Citation11,Citation35]. Conversely, patients with low self-efficacy (in terms of taking responsibility for their rehabilitation process) were very passive and voiced their expectations to be “rehabilitated” [Citation11].

Recognizing and acknowledging improvements helped patients with adhering to their prescribed exercises. Patients who could detect improvements in the activities they practiced described their motivation to carry out self-practice:

“The first time… I managed it once, toward the end of the study I managed it 15 times in 30 seconds. It was the highlight of the study” [Citation36].

Interest in the practiced activity is another element voiced by participants that could make them either fully engage in self-practice or, on the contrary, disappointed and bored to the point of giving up. Patients had a clear preference for practicing activities over doing repetitive movements.

“Once I got home all the exercises they had been showing me were so damn boring I tried incorporating the exercises into the daily things I did…” [Citation12]

This interest seems to interact with acknowledging improvement as a result of the activity; while the practice of repetitive movements is essential to promoting motor ability, the functional recovery of the affected side is perceived by patients as a more obvious landmark in their rehabilitation process:

“It’s exciting, when I can, actually, make something happen with my brain with my affected side” [Citation37].

Patients’ emotional ability to overcome hurdles, such as the initial shock after the stroke [Citation11] or the frustration after failing different tasks [Citation37] was found to influence adherence to self-practice. Those more severely affected by the stroke seemed to have a harder time confronting failure:

“The constant reminder of the losses and the frustration of repeated failure overwhelmed those with severe paresis. Not knowing what to do or how to get help eroded the will to continue” [Citation12].

A further hurdle expressed by patients in reviewed papers was the ability to overcome exercise-related pain and the fear of harming when practicing without professional help [Citation12].

Analytical theme 2: identifying self-practice as a team effort

At first glance, it does not make sense to identify self-practice with other entities except for the involved individual (the patient). However, after analysing the existing data in the context of stroke diagnosis, this interpretation of “self-practice” should be carefully reconsidered. It does not only involve the patient, but also the patient’s surroundings; both professionals and non-professionals fulfilled a certain role in this practice and were perceived by most patients as indispensable to their training process.

Health professionals have a role in self-practice beyond its prescribing. Patients reported that their adherence to self-practice was affected by professionals’ recommendations [Citation24]. Patients also referred to the input from healthcare professionals as what gave them hope “without hope, means without expectations, I have to do exercises” [Citation24]. However, patients reported that their hopes were sometimes dashed by specific input from healthcare professionals. A poor prognosis could break the patient’s spirit and diminish adherence to the point that they would “give up” [Citation12]. Other patients reacted differently, and were more engaged as a result of a poor prognosis, using it as a goal to prove the professionals wrong:

“Because that doctor knocked me so far down with what she said I fought her, not me” [Citation12].

Stroke survivors might team up with their caregivers to be helped with self-practice for different reasons. In some cases, they joined forces to pursue their common goal of recovery for the patient. The caregiver is then someone that cares a lot for the patient’s well-being: “for her (my daughter) I was her only lifebuoy… So, she did everything she could” [Citation35]. However, sometimes teaming up in this way produced stress, when the spouse/caregiver was overly bossy or pushing the patient:

“Especially as the spouse believes that one is capable of doing more […], being a bit more precise or faster, or adding another quarter or half hour…as a stroke patient says: Man, I’ve been at this for an hour now, that’s enough” [Citation36].

Social and family support could have a significant influence on patient's adherence to a prescribed program. Support went beyond verbal feedback, and patients were actually helped by their caregivers in doing the prescribed exercises. However, when the caregiver had to take part in the activity, the patient could become dependent on this person. It is possible, at that point, that the patient may feel a burden to their caregiver. This dependency may lead to disengagement when the caregiver is not present [Citation24] and decreased motivation because of “the inconvenience associated with frequent adjustment of heavy parts, making it impossible to set up without his caregiver’s help” [Citation38].

Analytical theme 3: self-practice that is grounded in one’s reality

Beyond the individual personality traits and a team approach to the process, adherence to self-practice can also be influenced by practical factors that make up the circumstances of a patient’s life. Less complex and more practical than previously mentioned ones, these factors range from the cost of therapy and the patient’s place of residence about the therapist’s clinic to lack of time due to a heavy schedule and available energy resources. In the papers reviewed, these factors were reported to affect a patient’s level of adherence to self-practice.

Some patients appreciated the comfort of practicing at home and the scheduling flexibility of such programs (e.g., if they were employed), and felt that this approach was more cost-effective:

“It’s actually a bonus for those not so well off, where you don’t need to worry about money. You can just continue your exercises” [Citation38].

Others described the energy trade-off between their life chores and activities on one hand and the prescribed practice program on the other. It is the dilemma between doing your best to survive at a given moment against practicing so you will have better survival options in the future. The best expression of this trade-off was found in the following quotation:

“…I noticed the longer I needed to use my hand at work to do something the harder it got to do anything with my hand at all” [Citation36].

After the stroke, patients were fighting to regain their life in the first phases of recovery. When they got back to their daily life, things were more difficult than they used to be. Therefore, finding time to practice was even harder in this new reality.

Post-stroke fatigue was mentioned by patients in the reviewed studies. Fatigue was mostly used by patients to highlight other issues and was not cited as a direct result of the practice. For example, to highlight scheduling issues, one person stated “my battery only lasted until noon” [Citation36]. However, patients did not report experiencing post-stroke fatigue as a factor that directly limited their adherence.

Many of the home programs that were studied were technology-based, including telerehabilitation [Citation38,Citation39], text messaging-based programs [Citation33], Ipad usage [Citation37], and computerized aphasia practice [Citation40]. Though technology allows instant and accurate feedback that is independent of another person and also increases interest, there were problems related to the operation of this technology. Setting up the equipment and handling minor technical and connection issues both seemed to have a dramatic impact on how patients felt [Citation36]:

“A lot of it is setting up the equipment that we don’t want to do. I hate doing it…” [Citation38]

The severity of impairments was placed within this theme because it determines the feasibility of participation in self-practice. While incorporating the practice into daily tasks was recognized as not possible by patients with severe paresis [Citation12], they did mention that they lacked movement to work with, and therefore had no exercises they could practice:

“I can’t improve what I’ve got if I haven’t got anything” [Citation12].

Overarching theme: tailoring and personalization rather than standardization

In this review, data were drawn from patients sharing the diagnosis of “stroke.” However, they differed in terms of their age, previous lifestyle, habits, social support, financial abilities, etc. Furthermore, stroke presentation varies significantly in terms of what skills and functions are affected (i.e., movement, speech, cognition, etc.) and how much they are affected. Therefore, each theme that is mentioned above cannot be inclusively considered as a facilitator or a barrier to self-practice. Each factor that may affect a patient’s adherence to self-practice should be judged as a facilitator or barrier for a specific patient in a specific context. For example, for some patients, having a determined caregiver may act as a facilitator, as they encourage the person through practice [Citation35]. In another situation, the patient would avoid the practice as they try to decrease their burden on that caregiver [Citation36].

Recognising all aspects of prescribed self-practice programs as unique to each individual is key to understanding these themes and how they interlink. For example, self-efficacy may change someone’s response to a specific structural barrier: a patient with high self-efficacy and a strong belief in her ability to improve through self-practice may not let structural limitations, such as space in her house, deter her. In contrast, for a patient with low self-efficacy that may decrease participation [Citation34]. For patients with specific character traits, being helped by a caregiver will lead to the pursuit of mutual goals and enjoyment of the process together, while others may feel they are a burden and will therefore prefer practicing independently, or not at all [Citation36].

The synthesis of papers included in this review may be presented using the model outlined in . The three analytical themes serve as a triad of pillars that uphold adherence to self-practice. Each of these pillars may support adherence or, on the contrary, endanger its structure. The presence of all pillars is crucial for adherence to continue. All factors are dependent on each other and, therefore, interact. Hence, when choosing a prescribed exercise/program for an individual, these three pillars (i.e., “self,” “team,” and “reality”) should be taken into consideration by healthcare professionals. These pillars may only provide support if a personalized approach is adopted, with each pillar considered individually by the healthcare professional, for each patient.

Discussion

This thematic synthesis has drawn upon a corpus of qualitative literature about stroke survivors’ thoughts and explanations about adherence to prescribed self-practice outside of clinical settings. It used a systematic search to retrieve relevant literature and a thematic synthesis to combine the results for a more nuanced understanding of the discussed topic.

This synthesis makes a unique contribution to the literature by presenting a summarizing model that emphasizes the importance of tailoring rather than standardizing self-practice programs. It is underpinned by the three analytical themes produced from the synthesis, which highlight the importance of considering the needs or role of the “self,” the team (including caregivers and professionals), and the patient’s daily reality (into which they are expected to schedule self-practice sessions).

The current review considers “tailoring and personalization rather than standardization” to be the overarching theme. Luker’s review, also covering stroke survivors’ experiences with physiotherapy, identified “patient-centered therapy” as one of nine themes. Luker’s review focused on the inpatient setting, while the current review focuses on a later phase of rehabilitation outside the clinical setting, where formal therapists are not present. Patients that are in inpatient settings are encouraged by the presence of their healthcare professionals. Outside the formal clinical setting, without a therapist present, patients need to push themselves. Hence, adherence in the latter context is influenced by the personalization of the patient’s practice. Without this personalization, the practice may be easily neglected.

At the time of writing we are facing, on a global scale, the COVID 19 pandemic. It highlights the importance of our overarching theme; personalising self-practice seems necessary given the contextual factors associated with COVID. These might include having less direct social support (e.g., because of an inability to see family members), feeling anxious about the pandemic and, thereby, lacking mental and physical energy to undertake prescribed activities, or having children at home more often or family members working from home putting pressure on space and time to engage in self-practice.

Compared to existing literature, patients’ “self” characteristics that were uniquely emphasized in the current synthesis are “patients experience with healthcare” and “interest in the practiced activity.” Patients who have had a stroke often face an exceptionally long and challenging rehabilitation process, which is full of contradictory and confusing messages conveyed by healthcare professionals [Citation10]. This is probably why even motivated patients quoted in the current review did not always adhere to a specific self-practice program.

Post-stroke fatigue is a much-discussed topic in the literature [Citation41]. In one study it was described as the most frequent symptom during the three months after a stroke [Citation42]. In another, it was recognized as the key reason for the non-adherence of stroke survivors to cardiac maintenance home exercises [Citation43]. However, even though fatigue was coded twice in the current review [Citation36,Citation40], it was not presented as a significant concept in any of the reviewed studies. A possible reason may be the difference like recovery-targeted exercises. While recovery-aimed activities require repetitions, graded accuracy, and coordination, they are usually less physically demanding by nature [Citation44].

Implications for practice

In light of our results, a typical healthcare professional is advised to consider the many individual factors (listed as “descriptive themes” in ) when prescribing self-practice exercises to stroke survivors. The required input to support a patient’s adherence will therefore be different for every patient. To maximise this process of facilitating adherence, the prescriber may be required to have a deeper, more personal connection with a patient. The relationship – the “therapeutic alliance” – between therapist and stroke patient is a topic that has been thoroughly explored in the literature [Citation45]. The nature of this relationship, including empathy and even the mutual sharing of personal information between the patient and therapist, is found to affect rehabilitation outcomes [Citation45]. Considering the lack of therapy time and the shortage of existing recourses, clinicians must decide how to develop this relationship, to facilitate adherence to self-practice prescribed as a follow-up to outpatient sessions.

Limitations

Limitations of our review include that it only applies to discharged stroke survivors and covers the adherence they have only to recovery-targeted interventions. Another weakness may be the use of the “qualitative” filter in our search strategy. The use of this filter in systematic reviews has been questioned because of the mal-indexing of qualitative papers in some databases [Citation46]. Furthermore, our search strategy did not include grey literature. However, it should be noted that as we conducted a configurative rather than an aggregative review [Citation47], we were able to locate a range of data that enabled us to produce a new understanding of the topic as would be expected from this type of review. The decision not to exclude papers based on their poor quality (as identified in the appraisal) may also be considered a limitation to our review, although this is not uncommon when working with qualitative data.

Conclusion

The practice of prescribed activities and exercises is required to promote the recovery of stroke survivors. In less acute phases of rehabilitation, self-practice is emphasized. However, adherence to prescribed self-practice is often poor. Therefore, it is essential to identify and understand factors that patients experience as influencing their adherence to self-practice. Our review emphasizes the importance of tailoring self-practice programs to patients’ situations and preferences, and highlights how adherence can be shaped by self, others (the team of prescribing therapists and caregivers), and an individual’s everyday reality.

appendix1-Casp_table.docx

Download MS Word (91.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests nor conflict of interests.

References

- Murray CJL. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210.

- Virani S, Alonso A, Benjamin E, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e151.

- Saka O, McGuire A, Wolfe C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):27–32.

- Hall R, Khan F, O'Callaghan C, et al. Ontario stroke evaluation report 2014: on target for stroke prevention and care; 2014.

- Allen C. Stroke: a practical guide to management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(6):678–679.

- Legg LA. Therapy‐based rehabilitation services for stroke patients at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2010(1):CD002925.

- Foley N, McClure JA, Meyer M, et al. Inpatient rehabilitation following stroke: amount of therapy received and associations with functional recovery. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(25):2132–2138.

- Legg P, Langdhorn P, Outpatient Service Trialists. Rehabilitation therapy services for stroke patients living at home: systematic review of randomised trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9406):352–356.

- Shipley J, Luker J, Thijs V, et al. How can stroke care be improved for younger service users? A qualitative study on the unmet needs of younger adults in inpatient and outpatient stroke care in Australia. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;42(12):1–8.

- Wiles R, Ashburn A, Payne S, et al. Discharge from physiotherapy following stroke: the management of disappointment. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(6):1263–1273.

- Kåringen I, Dysvik E, Furnes B. The elderly stroke patient's long-term adherence to physiotherapy home exercises. Adv Physiother. 2011;13(4):145–152.

- Barker RN, Brauer SG. Upper limb recovery after stroke: the stroke survivors' perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(20):1213–1223.

- Lohse KR, Lang CE, Boyd LA. Is more better? using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2053–2058.

- Birkenmeier RL, Prager EM, Lang CE. Translating animal doses of task-specific training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: a proof-of-concept study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(7):620–635.

- Lang CE, MacDonald JR, Reisman DS, et al. Observation of amounts of movement practice provided during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1692–1698.

- Lun V, Pullan N, Labelle N, et al. Comparison of the effects of a self-supervised home exercise program with a physiotherapist-supervised exercise program on the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):971–975.

- Oesch P, Kool J, Hagen K, et al. Effectiveness of exercise on work disability in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain: systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(3):193–205.

- Simek EM, McPhate L, Haines TP. Adherence to and efficacy of home exercise programs to prevent falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of exercise program characteristics. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):262–275.

- Keytsman C, Pieter VN, Jan S, et al. Periodized home-based training: a new strategy to improve high intensity exercise therapy adherence in mildly affected patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;(28):91–97.

- Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, et al. Factors influencing commencement and adherence to a home-based balance exercise program for reducing risk of falls: perceptions of people with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(7):1172–1182.

- Basaran A, Karadavut KI, Uneri SO, et al. Adherence to home exercise program among caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Turk J Phys Med Rehab. 2014;60(2):85–91.

- Crizzle AM, Newhouse IJ. Themes associated with exercise adherence in persons with Parkinson's disease: a qualitative study. Occup Ther Health Care. 2012;26(2–3):174–186.

- Ramas J, Courbon A, Roche F, et al. Effect of training programs and exercise in adult stroke patients: literature review. Ann Réadapt Méd Phys. 2007;50(6):430–444.

- Mahmood A, Nayak P, Kok G, et al. Factors influencing adherence to home-based exercises among community-dwelling stroke survivors in India: a qualitative study. Eur J Physiother. 2019;23:48–54.

- Rich M, Ginsburg KR. The reason and rhyme of qualitative research: why, when, and how to use qualitative methods in the study of adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(6):371–378.

- Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, et al. Stroke survivors' experiences of physical rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1698–1708.e10.

- Lawrence M, Pringle J, Kerr S, et al. Stroke survivors' and family members' perspectives of multimodal lifestyle interventions for secondary prevention of stroke and transient ischemic attack: a qualitative review and meta-aggregation. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(1):11–21.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

- Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(2):149–154.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- Olafsdottir SA, Jonsdottir H, Bjartmarz I, et al. Feasibility of ActivABLES to promote home-based exercise and physical activity of community-dwelling stroke survivors with support from caregivers: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):562.

- Harrison M, Palmer R, Cooper C. Factors associated with adherence to self-managed aphasia therapy practice on a computer–a mixed methods study alongside a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. 2020;11:582328.

- Fors U, Kamwesiga JT, Eriksson GM, et al. User evaluation of a novel SMS-based reminder system for supporting post-stroke rehabilitation. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2019;19(1):122.

- Gillot AJ, Holder-Walls A, Kurtz JR, et al. Perceptions and experiences of two survivors of stroke who participated in constraint-induced movement therapy home programs. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(2):168–176.

- Vloothuis J, Depla M, Hertogh C, et al. Experiences of patients with stroke and their caregivers with caregiver-mediated exercises during the CARE4STROKE trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;42:698–704.

- Stark A, Farber C, Tetzlaff B, et al. Stroke patients' and non-professional coaches' experiences with home-based constraint-induced movement therapy: a qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33(9):1527–1539.

- Donoso Brown EV, Dudgeon BJ, Gutman K, et al. Understanding upper extremity home programs and the use of gaming technology for persons after stroke. Disabil Health J. 2015;8(4):507–513.

- Tyagi S, Lim DSY, Ho WHH, et al. Acceptance of tele-rehabilitation by stroke patients: perceived barriers and facilitators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(12):2472–2477.e2.

- Chen Y, Chen Y, Zheng K, et al. A qualitative study on user acceptance of a home-based stroke telerehabilitation system. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;27:81–92.

- Palmer R, Enderby P, Paterson G. Using computers to enable self-management of aphasia therapy exercises for word finding: the patient and carer perspective. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2013;48(5):508–521.

- Lerdal A, Bakken LN, Kouwenhoven SE, et al. Poststroke fatigue–a review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):928–949.

- Mona B. The first year of rehabilitation after a stroke – from two perspectives. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17(3):215–222.

- Jurkiewicz MT, Marzolini S, Oh P. Adherence to a home-based exercise program for individuals after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(3):277–284.

- Schreiber J, Sober L, Banta L, et al. Application of motor learning principles with stroke survivors. Occup Ther Health Care. 2001;13(1):23–44.

- Bishop M, Kayes N, McPherson K. Understanding the therapeutic alliance in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;43:1074–1083.

- Flemming K, Briggs M. Electronic searching to locate qualitative research: evaluation of three strategies. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(1):95–100.

- Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):28.

- Wallace SE, Donoso Brown EV, Saylor A, et al. Participants' perceptions of an aphasiafriendly occupational therapy home program. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2018;25(8):599–609. DOI:10.1080/10749357.2018.1517492.