Abstract

Purpose

Although most clients on work disability benefits face multiple problems, most traditional interventions for (re)integration focus on a single problem. The aim of this study was to evaluate the “Comprehensive Approach to Reintegrate clients with multiple problems” (CARm), which provides a strategy for labour experts to build a relationship with each client in order to support clients in their needs and mobilize their social networks.

Methods

This study is a stratified, two-armed, non-blinded randomized controlled trial (RCT), with a 12-month follow-up period. Outcome measures were: having paid work, level of functioning, general health, quality of life, and social support.

Results

We included a total of 207 clients in our study; 97 in the intervention group and 110 in the care as usual (CAU) group. The clients’ mean age was 35.4 years (SD 12.8), 53.1% were female, and 179 (86.5%) reported multiple problems. We found the CARm intervention to have no significant effects superior to those of the CAU group on all outcomes.

Conclusion

As we found no superior effect of the CARm intervention compared to CAU, we cannot recommend widespread adoption of CARm. A process evaluation will give more insight into possible implementation failure of the intervention.

Most traditional interventions for (re)integration into the labour market are problem-centred, i.e., focusing on a single problem, and have limited effectiveness in persons with multiple problems.

A strength-based intervention may be suitable for vocational rehabilitation and disability settings, since it contains many elements (e.g., being strength-based, focused on clients’ wishes and goals, and involving activation of the social environment) also likely to improve chances of re-employment of persons with multiple problems.

In this study a strength-based intervention did not show a superior effect on paid employment and functioning within one year follow-up compared to care as usual in people with multiple problems on a work disability benefit.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Work disability is among the greatest social and labour market challenges for policy makers in many Western welfare states [Citation1]. It is not only a burden involving individual suffering and the public expenses of disability benefit, but it is also a (human) right of people with disabilities to participate in society and work, as secured in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability [Citation2]. To improve labour market prospects and reduce inequalities, several countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) introduced active labour market policies, aimed at integrating the unemployed in general [Citation3], and people with disabilities in particular [Citation1,Citation3]. Where these active labour market policies proved to be effective for unemployed benefit recipients in general, they appeared to be less successful for persons on disability benefits, especially those facing multiple problems [Citation4,Citation5].

Previous studies have defined and described multiple problems in different ways, referring to them as multiple barriers, multiple disadvantages, numerous problems, or just problems [Citation4,Citation6–11]. To comply with national studies, our study has defined having multiple problems as follows: Persons have multiple problems when they have to deal with two or more related and possibly reinforcing problems for a longer period of time, and they are unable to develop and conduct adequate management to control or solve the problems; this results in problematic participation in society and the labour market [Citation6]. Because multiple problems are interconnected and interact with each other, they cannot be addressed in isolation from one another [Citation4,Citation12,Citation13]. Due to multiple problems, people seem to get into a vicious circle of solving one problem only to be confronted with the next [Citation12]. Previous research has shown that the prevalence of multiple problems among people on work disability benefits is high, and can increase up to 10 problems per individual [Citation13,Citation14]. In our previous studies we found that, besides health issues, most clients on work disability benefit perceived additional problems such as relational problems, financial problems, domestic problems, addiction, and educational problems [Citation13,Citation15]. For people with disabilities the chances to find or keep work were negatively affected by these multiple problems [Citation6,Citation7]. Furthermore, the combined effect of these problems meant that persons with more problems ran a greater risk of unemployment; for example, persons with six problems had a 90% risk of unemployment [Citation7].

Most traditional interventions for (re)integration into the labour market are problem-centred, i.e., focusing on a single problem, and seeking expert and compensatory support for each problem separately. These interventions have limited effectiveness in persons with multiple problems [Citation5,Citation6]. Previous studies within multi-problem families and in psychiatry indicated that activating people’s own strengths is an important tool for intervention, as they themselves may have personal and social resources, as well as strengths, to solve their problems [Citation16,Citation17]. A recent systematic review of research regarding the use of strength-based approaches in mental health service settings found emerging evidence that the utilization of such an approach improves outcomes, including hospitalization rates, employment/educational attainment, and intrapersonal outcomes such as self-efficacy and sense of hope [Citation14]. Two studies measuring outcomes related to employment [Citation15,Citation16] found that the practical and cognitive skills needed for social and occupational/vocational functioning significantly improved in the strengths group as compared to case management services routinely delivered by the mental health centre [Citation15]. Moreover, Stanard [Citation16] found vocational/educational outcomes to be better in the experimental strengths group than in the control group.

Based on these findings, a strength-based intervention may also be suitable for vocational rehabilitation and disability settings, since it contains many elements (e.g., being strength-based, focused on clients’ wishes and goals, and involving activation of the social environment) also likely to improve chances of re-employment of persons with multiple problems. We therefore developed the Comprehensive Approach to Reintegrate persons with Multiple Problems (CARm) for use by labour experts at the Dutch Social Security Institute: the Institute for Employee Benefit Schemes (UWV). In the Dutch social security system, labour experts play a key role in supporting the re-integration process of persons with a work disability and remaining workability. The CARm intervention is adapted from the Comprehensive Approach to Rehabilitation (CARe), a well-known intervention in mental health care in the Netherlands, aimed at improving the quality of life of persons with psychological or social vulnerabilities by focusing on their strengths, helping to realize their wishes and goals, and obtaining access to their living environment and social networks [Citation18]. CARe is based on the Strength Model of Rapp, a theoretical model from the 1980s focusing on the personal qualities, talents, and strengths of persons with psychiatric disabilities, and on their environment [Citation10]. The model includes the following principles: (1) focus on the person’s strengths rather than on pathology and limitations; (2) recognition of the relation between professional and client as primary and essential; (3) client-based interventions; (4) view of the community as a source of support and possibilities rather than an obstacle; (5) interventions offered in and by the community; and (6) people helped to recover, learn, grow and change.

To acquire more scientific knowledge on the applicability and effectiveness of CARm in disability settings, we conducted a feasibility study as an important first step to determine whether the intervention was appropriate for further testing [Citation15]. We concluded that the CARm intervention was feasible and promising, and therefore its effectiveness should be studied [Citation15].

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the CARm intervention on (re)integration into paid employment, and level of functioning, in a sample of disability benefit recipients facing multiple problems compared to those receiving care as usual. Since the Strengths model focuses on quality of life and is a recovery-oriented approach, outcomes on work status and functioning alone could be too one dimensional. Therefore, we also studied the effectiveness of the CARm intervention on perceived general health, quality of life, and social support.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was carried out as a stratified (rural and urban), two-armed (intervention and control), non-blinded randomized controlled trial (RCT), with a fixed follow-up period of 12 months. The Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), the Netherlands, approved recruitment, consent and field procedures. The trial was registered at the Dutch Trial Register (Nederlands Trial Register) (NTR5733). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Design and reporting in this study is in line with the “CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomized control trials” [Citation19].

We conducted this trial in collaboration with ten districts of the Public Employment Service, a division of the UWV. The CARm approach was offered by a trained labour expert of the UWV. In the Dutch social security system, according to the Work and Income Act (WIA) workers can apply for disability benefits after two years of sick leave [Citation20]. After a medical disability assessment by an insurance physician of the UWV, clients can receive either full and permanent benefits, full but non-permanent benefits, partial benefits, or no benefits for work disability. Insurance physicians assess clients as having no remaining workability if they: (1) lose their total workability within three months, (2) have a terminal disease with a life expectancy indicating that they will lose their total workability within foreseeable time, (3) have fluctuating workability, (4) are hospitalized, or (5) are not self-reliant due to a severe mental or physical disorder [Citation21]. Clients assessed with remaining workability are referred to a labour expert who evaluates whether they are incentivized to continue in paid employment with their current employers, or whether they should enrol in a new, more appropriate job, according to their remaining workability. These labour experts play a key role in supporting the re-integration process. Moreover, the labour expert is usually responsible for clients with more complex multiple problems. In current practice, in their role as work reintegration professionals labour experts focus mainly on the client and his or her limitations due to work disability.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome measure level of functioning, measured using the World Health Organization Disability Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) using G*Power software version 3.1.9.2 [Citation22,Citation23]. Based on an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.50, a power of 0.80, an alpha of 0.05, an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.20, and a loss to follow-up of 25%, the desired sample size would be 440 clients in total, 220 clients per group [Citation24–26]. There was a budget to provide two full training sessions for the labour experts. We intended to include a maximum of eight to ten labour experts per training session to have a good interaction between the participants. Based on these conditions, we decided to include 20 labour experts in the intervention group, and 20 labour experts in the care as usual group. To include the calculated sample size, each labour expert would have to provide 11 clients for the study. During an information meeting prior to the start of the study, labour experts were informed about the number of clients to be recruited. They believed it was feasible to include 11 clients, who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study population and recruitment

To select participants for this study we used a two-step procedure. First, we invited eligible labour experts to participate. Every labour expert working at the Public Employment Service of the UWV was eligible for recruitment. In total this group consisted of 353 labour experts, divided over 11 different districts of the UWV in the Netherlands. The managers of the UWV selected one contact person per district. We then asked these contact persons to forward to all labour experts in their district our invitation to participate in the study. As the management of one district decided not to participate, 10 districts were involved in the study. We sent one reminder. Those who were first to agree to participate were included in the study. We held a meeting to inform all included labour experts about their role in the study. Recruitment of the labour experts took place from February until March 2016.

In the second step, we asked clients to participate in the study. They were recruited by the participating labour experts. Clients who met the following criteria were found eligible: clients who had been granted work disability benefits and had been assessed with residual work capacity but were unemployed or not working the complete number of hours according to their residual work capacity, having an age of 18–65, and being able to understand and write Dutch. When clients agreed to participate, their name, address and e-mail address were collected by the labour expert and sent to the research assistant. The research assistant then mailed a letter to inform the client in more detail about the study, with a consent form and the first questionnaire. After receiving the informed consent form, the researcher included the client in the study. Clients were asked to complete questionnaires at baseline, and after three- and 12-months follow-up. If they did not respond, a reminder was sent after one and two months by phone call, e-mail and/or letter. Furthermore, labour experts were urged to include as many clients as possible by regularly sending emails, telephone calls and personal contact. Newsletters were send to keep the labour experts updated on the current inclusion numbers and the aim of the sample size. Clients were recruited by labour experts from April 2016 through December 2016. After the follow-up, one year of data collection continued, until January 2018 for questionnaire data, and until April 2019 for register data on work status.

Randomization

Randomization took place at labour expert level. In order of registration, labour experts were randomized to the intervention or care as usual groups (CAU). A computer-generated randomization scheme used random permuted blocks of four labour experts, stratified to rural and urban districts to ensure a balanced assignment of location-specific employment rates. The districts were divided into rural and urban based on the number of inhabitants, the presence or absence of major cities, and the employment rate in the specific district. This resulted in five urban and six rural districts.

Randomization was performed by an independent methodological advisor who was blinded to the identity of the labour experts. After randomization, the advisor informed the researchers about the labour expert allocation.

The intervention – CARm

The CARm intervention comprises four elements: (1) The labour expert becomes acquainted with the concept of the strength-based method; (2) the labour expert drafts a Personal Profile of the client, containing information on client’s current situation, needs, experiences, strengths, successes, abilities and skills; (3) the labour expert and client make an inventory of external resources in the client’s social network: who are important for you, how is the relationship with the people in the social network, what was the support in the past, who can help you to achieve your goals; and (4) based on this profile, the client and the labour expert jointly develop a Participation Plan to prioritize the client’s goals, activate the network, and tackle the client’s problems. The labour experts are responsible to build an individual relationship with the client, based on mutual respect, to support the client in his/her needs – focusing on strengths rather than limitations – and to mobilize the client’s social network. In addition, they arrange for a prioritization of the client’s goals and problems, with an emphasis on abilities. For this purpose, the labour experts received a five-day training in the CARm method. The training module focused on practical implementation of knowledge and skills during a five-day workshop – two whole days to transfer theoretical knowledge about the CARm method, and three half days to implement practical skills. The training was based on the book “Supporting Recovery and Inclusion: Working with the CARe model” by den Hollander and Wilken [Citation27] and a training folder on the CARm method written by the research team. The training folder contained tools to help the labour expert and the client to draft a profile, make an inventory of the social network, and develop a participation plan. To avoid contamination, the labour experts in the CARm intervention were asked not to discuss the content of the method and training with their colleagues.

Care as usual

In the care as usual (CAU) group, the majority of reintegration tasks were executed by a reintegration company, thereby minimizing the contact between labour expert and client. The CAU group did not receive additional training as part of this study. Therefore, the CAU group was not acquainted with a strength-based method for reintegration, as our training and study were the first available sources on this method. Furthermore, we tried to minimize the information which the labour experts in the CAU group received about the CARm intervention so that they would not be familiar with the details of the CARm method.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcomes of this study were paid employment and level of functioning.

Paid employment was measured using data on gross wages and social benefit pensions from the Dutch tax register, which were available through data linkage with Polis register data from UWV. Data on these income characteristics were available on a monthly basis, with a follow-up period of one year from the time of enrolment in the CARm trial. Paid employment was dichotomized into (yes/no) regarding receiving income from employment, according to the register data of UWV for the period of 12 months from inclusion.

Level of functioning was assessed using the World Health Organization Disability Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) [Citation22], and measured at baseline and 12 months. The WHODAS 2.0 is a practical, generic assessment instrument that captures the level of functioning in six domains of life: Understanding and Communicating (6 items), Getting around (5 items), Self-care (4 items), Getting along with people (5 items), Household activities (4 items), and Participation (8 items). All items of the WHODAS 2.0 have a five-point rating scale with answer options ranging from 1 = “no difficulty” to 5 = “extreme difficulty or inability to perform the activity.” In this study we used the total score as well as the domain score on participation to gain insight into clients’ ability to participate in society and work [Citation22]. Standardized total scores and subscale scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing increased difficulties in functioning. Cronbach’s alpha on the total score was 0.93, and for the participation domain 0.85, indicating good internal consistency.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcomes of this study were perceived general health, quality of life, and social support.

General health was measured by the first question of the SF-36: RAND-36: “In general, would you say your health is…?” at baseline, and at three and 12 months [Citation28,Citation29]. The item has a 5-point Likert scale (1 = excellent to 5 = poor) [Citation30].

Quality of life was assessed with the World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQoL-Bref) [Citation31,Citation32] at baseline and 12 months, including questions on four domains: physical health (7 items), psychological functioning (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and environmental opportunities (8 items). All items were scored on a four-point scale. Standardized domain scores ranged from 0 to 100, higher scores indicating a better quality of life. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.70 to 0.86 on the four domains, respectively.

Social support was assessed with the Social Support List-Interactions (SSL-I), and the Social Support List-Discrepancies (SSL-D) [Citation33]. These were assessed at baseline, and at three- and 12-months follow-up. The SSL-I is a 12-item questionnaire which measures three types of support: everyday support, support in case of problems, and esteem support. All questions are scored on a four-point scale from 1 = seldom or never, to 4 = very often. The overall sum score (possible range from 12 to 48) from the SSL-I was used, including all items. Higher scores indicate more social support. Cronbach’s alpha on the total score was 0.92, indicating high internal consistency. The SSL-D questionnaire consists of 34 items which measure the degree to which the obtained support corresponds to the respondent’s needs. The questions were scored on a four-point scale from 1 = I miss it, I would like to have more of it, 2 = I do not really miss it, but it would be nice if it happened more often, 3 = just enough as it is, I do not want it to be more or less often, 4 = it happens too often, it would be nice if it happened less often. Scores were recoded according to the manual [Citation33]; the overall score had a possible range from 34 to 102, with higher scores indicating a greater lack of support. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.97, indicating high internal consistency.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, a questionnaire was used to assess data on clients’ sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender (male/female), education (low = primary school, lower vocational education, lower secondary school; medium = intermediate vocational education, upper secondary school; and high = upper vocational education, university), urbanization (urban/rural, measured at labour expert level), living situation (living alone: yes/no), being breadwinner (yes/no). Perceived problems were assessed by a self-constructed questionnaire [Citation13], asking participants whether they experienced problems in the following areas: (1) physical health, (2) mental health, (3) financial problems, (4) care for family or children, (5) educational mismatch (too low or not appropriate), (6) problems with the Dutch language, (7) problems with police or justice, (8) housing, (9) addiction, and (10) domestic violence. These areas were derived from the categories of multiple problems, selecting the problems most suitable for the target population out of the four domains (psychological problems, cultural problems, economic problems, and normative problems) as reported by Statistics Netherlands (CBS) [Citation34]. Multiple problems (yes/no) was defined as experiencing two or more problems. From the UWV register data we collected data on receiving disability benefits (yes/no), type of diagnoses (dichotomized into mental [e.g., depressive episodes, mild mental retardation] and physical diseases [e.g., cardiovascular disorders, lumbar disc disorder]) and how long (in years) the client had received disability benefits at baseline.

Regarding labour experts, socio-demographic data were collected at baseline by a questionnaire. Data included questions on age, gender, and working years as a labour expert. The working location of the labour expert (urban or rural) determined the client's allocation to an urban or rural area in the Netherlands.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed at client level and according to the intention-to-treat principle. The chi-square test (ordinal and nominal variables) or t-test (mean scores) were used to compare differences on baseline characteristics between the intervention and CAU groups. For the primary outcome on having paid employment, we performed logistic multilevel analyses. For the primary outcome, level of functioning, and all secondary outcomes we performed linear multilevel analyses. For skewed distributions regarding questionnaire data (SSL-D), we used gamma distributions in the linear multilevel models [Citation35–37].

We had planned to incorporate three levels (labour expert, client, observation) in all models. However, the variance component of the labour expert level was zero in the empty model and remained zero in the unconditional growth model. Therefore, we decided to incorporate two levels (client and observation) in the models. We tested for interactions between the intervention and time to follow-up by incorporating interaction terms in all multilevel analyses. All analyses included all available observations of the specific questionnaires (baseline and 12 months data for functioning and quality of life; baseline, three-months and 12 months data for general health and social support) and were adjusted for age, gender, education, urbanization, living situation, being breadwinner, diagnoses, and duration of disability benefits at baseline. With regard to the continuous confounders, age at baseline was centered on 36.12 years, and the duration of disability benefits at baseline was centered on 4.46 years in the multilevel analyses. Multilevel analyses were performed with Statistical Packages SAS version 9.4 (Proc Glimmix and Proc Mixed) and SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc. Chicago). For all analyses a two-tailed p-level of <0.05 was considered an indication of statistical significance.

Results

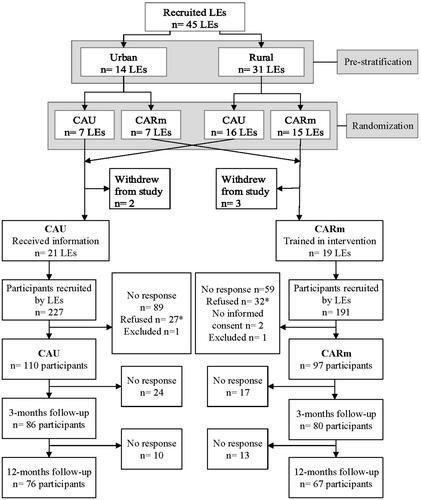

In total, 45 labour experts were recruited, 22 of whom were allocated to the CARm intervention and 23 to the CAU group. After randomization, five labour experts − 3 from the intervention and 2 from the CAU group – withdrew from the study for the following reasons: busy work schedule, change of workplace or division, or end of contract. Therefore, the final sample included 40 labour experts − 19 in the CARm intervention and 21 in the CAU intervention. An overview of the recruitment flow is presented in . Baseline characteristics of the labour experts are presented in . No differences between labour experts in the CARm intervention and the CAU group were found.

Figure 1. Flowchart of participant recruitment, allocation and outcome assessment.

Table 1. Characteristics of labour experts per study group.

Non-participation and loss to follow-up

During the recruitment phase, 418 clients were approached by the 40 labour experts; of these 59 (14.1%) were not willing to participate. Main reasons for refusing were: too burdensome, not interested, and health problems. The 359 (85.9%) clients who were willing to participate were sent the baseline questionnaire and an informed consent form. Of these, 148 clients did not respond, and 4 were excluded due to missing informed consent, or missing information needed for data retrieval from the UWV registers. In total, 207 clients were included in the study − 97 in the CARm intervention and 110 in the CAU group (). The number of clients included per labour expert ranged from 1 to 12. For the self-reported outcomes, 41 clients (n = 17 CARm, n = 24 CAU) were lost to follow up at three months, and another 23 (n = 13 CARm, n = 10 CAU) at 12 months ().

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the clients in the CARm intervention and CAU group are presented in . The mean age of the included clients was 35.4 years (SD 12.8), 53.1% were female, 30.4% had a low educational level, 34.3% were living alone, and 179 (86.5%) reported multiple (two or more) problems. The CARm intervention and the CAU group showed no differences in baseline characteristics of the clients, except for urbanization: 55.7% of the clients in the CARm intervention had been recruited by a labour expert from a rural district, whereas for the CAU group this was 71.8% (p=.016).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of clients per study group.

Primary and secondary outcomes

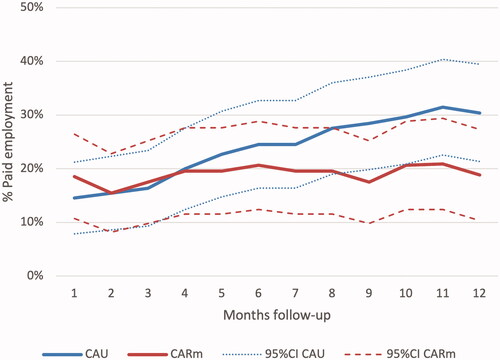

The results regarding the effectiveness of the intervention with respect to primary and secondary outcome measures are presented in and . Between the CARm and CAU groups, during follow-up we found no effect for paid employment (log Odds 1.62; 95%CI −0.42, 3.66), but a significant effect for time (Log Odds 0.35; 95%CI 0.26, 0.44), and for Time*CARm (log Odds −0.30; 95%CI −0.43, −0.18); this indicates no significant difference in paid employment at baseline, but a significant positive effect of Time, and a significant positive effect on paid employment over time in the control group compared to the CARm group ( and ).

Figure 2. Unadjusted paid employment rates per month of clients in CARm intervention and CAU groups.

Table 3. Logistic multilevel analyses of paid employment of clients in CARm intervention and CAU groups during 12 months follow-up.

Table 4. Linear multilevel regression analyses of questionnaire data of CARm intervention and CAU group clients using baseline to 12 months follow-up data.

During the 12 months follow-up, the clients in the CAU group improved significantly in their perceived functioning (estimated mean change score −4.451 [95%CI −6.541, −2.362]), whereas clients in the CARm intervention did not improve significantly (estimated mean change score 0.885 [95%CI −1.482, 3.251]). Further, we found no significant differences between the two groups over time ().

Regarding participation, the clients in the CAU group improved significantly during the 12 months follow-up (estimated mean change score −5.360 [95%CI −8.542, −2.719]), whereas the clients in the CARm intervention showed no significant change (estimated mean change score 0.321 [95%CI −2.998, 3.640]). We found no significant differences over time between the two groups ().

Regarding general health over time, we found no significant differences within nor between the two groups ().

For quality of life, the clients in the CAU group improved significantly on psychological functioning during the 12 months follow-up (estimated mean change 0.431 [95%CI 0.106, 0.757]). However, the clients in the CARm intervention showed no significant change over time (estimated mean change −0.069 [95%CI −0.444, 0.306]); regarding psychological functioning over time, no significant difference was found between the groups. The other domains of the quality of life questionnaire (physical health, social relations, and environmental opportunities) showed no significant differences within or between the two groups over time over time ().

The social support scores for both the CARm intervention and the CAU group on the SSL-I and the SSL-D showed no significant differences within nor between both groups over time ().

Discussion

Main findings

The present study showed no significant superior effect of allocation to the CARm trained labour expert over the CAU labour expert on the primary and secondary outcomes. In fact, the clients supported by a CAU labour expert scored significantly better on employment status over time, as well as on improvement on levels of functioning over time. We found no significant differences over time on functioning and participation in the CARm group, nor between both groups. Among secondary outcomes, regarding the domain psychological function in the quality of life questionnaire, the CAU group showed a significant improvement over time. Further, we found no significant differences in favour of the intervention group on any secondary outcome.

Interpretation of the findings

The absence of a superior intervention effect may have had several causes: (1) the follow-up time may have been too short in order to have an effect of the CARm intervention on employment status, due to a “lock-in-effect” [Citation38,Citation39]; (2) the CARm intervention may have sustained implementation or theory failure; (3) the participating labour experts may have consisted of a subgroup already specifically interested in using the offered methods, and by then applying them (partly) in their daily practice.

Regarding the first potential cause, the adverse effect of employment status may have been caused by a lock-in-effect, as initially described by Van Ours [Citation38], and further elaborated by Lechner et al. [Citation39]: participants entering a program or intervention to improve employment outcomes can be too busy following that program instead of spending time looking for a job. This leads initially to a negative effect on employment outcomes. Those who have completed programs have a greater probability of finding sustainable work than those who have not participated in a program, but these positive effects can take as long as three years to become evident [Citation38,Citation39]. In our study, the clients in the CARm intervention were supported by a comprehensive strength-based method to work on their perceived problems – problems that hinder (re)integration but are not necessarily work related. A possible lock-in effect may explain why we should not have expected to see a strong increase in employment status within one year of follow-up. Furthermore, our intervention aimed to reach sustainable employment rather than short-term employment.

Regarding the second possible cause, the absence of a positive intervention effect could also have been a result of implementation and/or theory failure. The aim of the CARm intervention was to have labour experts build individual relationships with clients, to develop tailor-made programs for reintegration, aimed at work resumption, as well as to support clients in their needs and mobilize their social networks. A participation plan was drafted jointly by labour expert and client in order to prioritize and tackle the client’s problems.

Implementation failure can occur at different levels, resulting in low fidelity of the intervention. At the organizational level, followed by the labour market policies, the budgets available for reintegration are limited, leaving labour experts only limited time to offer the intended support to their clients. Without building a relationship using a strength-based approach, drafting a profile, making an analysis of the network, and working with the client to draft a reintegration plan, the intervention cannot be effective. A major concern in the feasibility study was that because of the workload several labour experts sensed on the part of management not only a lack of support, but even disapproval, of (multiple) personal contact(s) with clients; such an attitude would conflict with the CARm methodology [Citation15], and would have made it impossible to provide the key elements of the intervention as planned. In order to know whether the labour experts in our sample experienced the same lack of management support, we conducted a process evaluation along with this effect study.

Additionally, the CARm intervention may have sustained theory failure, meaning that in spite of being implemented correctly, the intervention is not effective for our study population. The CARm intervention was based on the Strengths model as described by Rapp [Citation17]. Bitter et al. also performed an intervention study based on the same model: Comprehensive Approach to Rehabilitation [Citation18]. They studied the effect of their CARe intervention on rehabilitation of people with severe mental illnesses. Although all clients improved in quality of life over time, Bitter et al. also found no significant differences between the intervention and care as usual groups. They suggested that a possible reason for their lack of result might be theory failure: failure of the characteristics of the CARe methodology itself. They elaborated that earlier research on rehabilitation approaches indicated that effective elements of psychiatric rehabilitation are: focussing on the specific skills that are needed in a certain environment and actual access to that desired environment as soon as possible; integrating rehabilitation and psychiatric treatment; and combining skills training and offering support. In the CARe methodology these aspects were not elaborated explicitly [Citation11]. However, with the CARm intervention we targeted a rather different population of both professionals and clients than the CARe methodology and made severe adjustments to the CARe methodology accordingly. We have no indication that these adjustments were insufficient to make the methodology suitable for our target population. Nevertheless theory failure still might have occurred. The results of our process evaluation may provide more insight into this matter.

Regarding the third possible cause, because participation of labour experts in the study was voluntary, we may have especially reached labour experts already interested in using the methods provided in the CARm intervention, and therefore a selection bias might have occurred. If they had already applied its approach (partly) in their daily practice without our awareness, independent of being randomized to the CARm intervention or CAU group, this may have affected our study outcomes. The process evaluation conducted along with our effect study may give us more insight into this possible cause.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this study is the first effect study of a strength- based reintegration method for people on work disability benefits, and one of the few studies to use an intervention based on the strength method, compared to care as usual [Citation18,Citation40,Citation41]. Although Bitter et al. published their study on the effect of the CARe method, we adjusted the method and targeted a rather different population of both professionals and clients [Citation11,Citation18].

Because clients were recruited by labour experts working in all regions of the Netherlands, we were able to include a geographically representative sample of clients, from regions both rural and urban, and economically strong and less strong. Furthermore, for employment status and diagnosed disease we used register data, which are from an external source and minimise the chance of bias due to self-report.

A possible limitation of our study is a potential selection bias in both the labour experts and the clients. Participation of the labour experts was voluntary, and therefore we may have especially reached labour experts who were motivated in using the methods provided in the CARm intervention. Subsequently, as the recruitment of eligible clients was conducted by labour experts, so we had no insight into which clients were or were not selected for the study. However, our study sample of the participating clients shows a distribution of the clients over categories of the sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., gender, educational level), and no significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics (except for urbanization) between the CARm intervention and CAU group, suggesting that the selection by the labour experts was random and the randomization went as intended.

Furthermore, we were not able to include the previously calculated sample size. This may have affected our statistical outcomes. Although the results did not show a trend toward significance in favour of the CARm intervention, we can assume that the intervention would have had no significant superior effect over the CAU if the sample size had provided sufficient power.

Implications for research and practice

The majority (87%) of the participating clients perceived the presence of multiple problems [Citation13]. These clients experience a great distance from the labour market, and the time to find sustainable employment may take more than 12 months, especially when the intervention is focused not only on reintegration into work but also on other perceived problems, as well as on mobilising the social network and addressing strengths. Although our study did not show the CARm intervention to have a superior effect on paid employment compared to CAU, we are convinced that many elements of the CARm module fit well within modern labour market policies. Further in depth research is needed on the effect of the CARm module on other outcomes: whether the tailor-made program supports the needs of clients, mobilizes clients’ social networks, and leads to a decrease in the client’s perceived problems, which might be a first, but very important, step in the process of reintegration. Additionally, to confirm whether CARm participants indeed achieve better than CAU participants in return to paid employment and sustainable employment in the long run, a longer follow-up time than 12 months would be needed in order to overcome a possible locked-in-effect.

Conclusion

This is the first effect study on a strength-based reintegration method, CARm, for people with multiple problems on work disability benefits; we found the CARm intervention to have no superior effect when compared to CAU. We suspect multiple possible causes for the absence of a superior effect: a “lock-in-effect,” selection bias, theory failure; and/or failure of the implementation. Based on these results we cannot recommend a widespread adoption of CARm. Further, in depth evaluation of the process is needed, as well as additional research to study the effect of the CARm method on outcomes, such as decreased numbers of perceived problems of clients far separated from the labour market. Moreover, a longer follow-up period than one year should be used to evaluate its effect on sustainable paid employment.

Ethics approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), the Netherlands, approved recruitment, consent and field procedures. The trial was registered at the Dutch Trial Register (Nederlands Trial Register) (NTR5733). Design and reporting in this study is in line with the “CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomized control trials.”

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Acknowledgements

We thank our former research assistant Jeanique Ham for her contribution in logistics, organization and administration for this study. We also thank the participating labour experts from the Dutch Social Security Institute and their participating clients. Finally, we especially acknowledge our beloved colleague Bert Cornelius. Bert was till his death a major contributor to the design of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- OECD. Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264088856-en.

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- OECD. Activating the unemployed: what countries do. OECD Employ Outlook 2007 [Internet]. 2007. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/40777063.pdf.

- Dean H, MacNeill V, Melrose M. Ready to work? Understanding the experiences of people with multiple problems and needs. Benefits. 2003;11:19–25.

- Martin JP. Activation and active labour market policies in OECD countries: stylised facts and evidence on their effectiveness. IZA J Labor Policy. 2015;4:4.

- Bosselaar J, Prins R, Maurits E, et al. Multiproblematiek bij cliënten, verslag van een verkenning in relatie tot (arbeids) participatie [Clients with multiple problems. An orientation and report in relation to (labour)participation]. Meccano kennis voor beleid en AStri Beleidsonderzoek en-advies; Utrecht/Leiden: Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment; 2010. [In Dutch]

- Berthoud RM. Disadvantage in employment: a quantitative analysis. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2003.

- Blumenberg E. On the way to work: welfare participants and barriers to employment. Econ Dev Q. 2002;16(4):314–325.

- Perkins D, Nelms L. Assisting the most disadvantaged job seekers. In: Carlson E, editor. A future that works: economics, employment and the environment. Newcastle: Centre of Full Employment and Equity, University of Newcastle; 2004. p. 371.

- Lindsay S. Discrimination and other barriers to employment for teens and young adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1340–1350.

- Brongers KA, Cornelius B, Van Der Klink JJL, et al. Development and evaluation of a strength-based method to promote employment of work-disability benefit recipients with multiple problems: a feasibility study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):71.

- Audhoe SS, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Hoving JL, et al. Perspectives of unemployed workers with mental health problems: barriers to and solutions for return to work. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(1):28–34.

- Brongers KA, Hoekstra T, Roelofs PDDM, et al. Prevalence, types, and combinations of multiple problems among recipients of work disability benefits. Disabil Rehabil. 2021. DOI:10.1080/09638288.2021.1900931

- Singley S. Barriers to employment among long-term beneficiaries: a review of recent international evidence. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development; 2003.

- Brongers KA, Cornelius B, Roelofs PDDM, et al. Feasibility of family group conference to promote return-to-work of persons receiving work disability benefit. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(22):3227–3236.

- Sousa L, Ribeiro C, Rodrigues S. Are practitioners incorporating a strengths-focused approach when working with multi-problem poor families? J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;17(1):53–66.

- Rapp CA, Goscha RJ. The strengths model: a recovery-oriented approach to mental health services. 3rd ed. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Bitter N, Roeg D, van Assen M, et al. How effective is the comprehensive approach to rehabilitation (CARe) methodology? A cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):396.

- Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345(1):e5661–16.

- Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid. Wet werk en inkomen naar arbeidsvermogen [Work and Income Act] [Internet]. Netherlands; 2005. Available from: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0019057/2020-03-19.

- Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid. Schattingsbesluit Arbeidsongeschiktheidswetten [Disability Assessment Rule] [Internet]. Netherlands; 2000. Available from: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0011478/2021-01-01.

- Üstün TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, R J. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO disability assessment schedule WHODAS 2.0. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191.

- Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJL, de Boer MR, et al. Predictors of functional improvement and future work status after the disability benefit claim: a prospective cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):680–691.

- Pösl M, Cieza A, Stucki G. Psychometric properties of the WHODASII in rehabilitation patients. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(9):1521–1531.

- Campbell M, Grimshaw J, Steen N. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised trials. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;5(1):12–16.

- den Hollander D, Wilken JP. Supporting recovery and inclusion. Working with the CARe model. Uitgeverij SWP; 2015.

- Diehr P, Patrick DL, Spertus J, et al. Transforming self-rated health and the SF-36 scales to include death and improve interpretability. Med Care. 2001;39(7):670–680.

- Sloan JA, Aaronson N, Cappelleri JC, et al. Assessing the clinical significance of single items relative to summated scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(5):479–487.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233.

- The WHOQOL GROUP. Development of the world health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558.

- Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA. The world health organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial a report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):299–310.

- Van Sonderen E. The measurement of social support with the social support list-interactions (SSL-I) and the social support list-discrepancies (SSL–D). Dutch manual. Groningen: Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken; 1993.

- Bosselaar H, Maurits E, Molenaar-Cox P. Clients with multiple problems. An orientation and report in relation to (labour)participation. (In Dutch): Multiproblematiek bij cliënten. Verslag van een verkenning in relatie tot (arbeids)participatie). Meccano kennis voor beleid en AStri Beleidsonderzoek en-advies; 2010.

- Azuero A, Pisu M, McNees P, et al. An application of longitudinal analysis with skewed outcomes. Nurs Res. 2010;59(4):301–307.

- Malehi AS, Pourmotahari F, Angali KA. Statistical models for the analysis of skewed healthcare cost data: a simulation study. Health Econ Rev. 2015;5:11.

- Hammouri HM, Sabo RT, Alsaadawi R, et al. Handling skewed data: a comparison of two popular methods. Appl Sci. 2020;10(18):6247.

- van Ours JC. The locking-in effect of subsidized jobs. J Comp Econ. 2004;32:37–55.

- Lechner M, Miquel R, Wunsch C. Long-run effects of public sector sponsored training in West Germany. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2011;9(4):742–784.

- Medalia A, Choi J. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(3):353–364.

- Heer-Wunderink C d. Successful community living: a “UTOPIA”? A survey of people with severe mental illness in Dutch regional institutes for residential care. 2012. Available from: https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/successful-community-living-a-utopia-a-survey-of-people-with-seve