Abstract

Purpose

Cognitive rehabilitation research has progressed slowly, in part due to incomplete reporting of intervention content and delivery and the difficulties this produces for discerning program effectiveness. This knowledge gap can be reduced by providing detailed intervention descriptions. We document the content/ingredients and therapeutic targets of a cognitive rehabilitation program for adults with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment.

Methods

The documentation process used a method of participatory/collaborative research. Discussions with the clinical team identified session content/ingredients and therapeutic targets, which were then described using Body Functions, and Activities & Participation domains from the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF). Domains most frequently targeted by each clinician were identified as Primary Targets.

Results

Each clinician produced a detailed description of session content, implementation, and ICF-coded therapeutic targets. This revealed that the whole program targets 29 ICF domains, seven of which were identified as Primary Targets: Higher-level Cognitive; Attention; Memory; Emotional; Global Psychosocial, Temperament and Personality, and Conversation.

Conclusions

Documentation of treatment targets enabled identification of appropriate outcome measures which are now being used to investigate program efficacy. This step-by-step explanation of the documentation process could serve as a guide for other teams wanting to document their rehabilitation interventions and/or establish similar programs.

Incomplete reporting of intervention content and delivery contributes to difficulties in discerning the effectiveness of complex rehabilitation programs.

Current recommendations for rehabilitation intervention reporting suggest that these difficulties can be partially overcome by providing detailed descriptions of intervention content/ingredients and treatment targets.

Human and physical resources differ widely from one clinical setting to another and the existence of clear program descriptions can guide clinicians who wish to create similar programs.

Detailed descriptions of rehabilitation interventions are necessary to accurately measure patient outcomes and generate testable hypotheses about proposed mechanisms of action.

Program descriptions are needed for the development of treatment theories and the advancement of evidence-based practice in rehabilitation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Improvements in acute reperfusion therapies for stroke as well the development of specialised intensive care units for stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI) have led to improved survival and reduced disability in these populations [Citation1,Citation2]. Patients who in the past might have had severe sensorimotor disabilities and/or cognitive impairments can today have very few symptoms, and be allowed to return home after only a few days in hospital. Some of these patients, however, have mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment and experience difficulties in their everyday functioning which can stop them from returning to work or severely impair their ability to do their previous job (e.g., [Citation3–6]).

Holistic cognitive rehabilitation programs have existed in rehabilitation centres and hospitals for nearly 30 years, and clinicians in many countries have extensive experience with the delivery and evaluation of these programs (see for example [Citation7–12]). Unlike modular programs (that focus on a single function), holistic programs include a wide range of treatment targets and typically have a global focus that includes activity and participation as well as organic function. They use both restorative and compensatory approaches and include an integrated therapeutic environment that provides group- and individual- based content. They often use group dynamics as a therapeutic tool, and their focus is on raising awareness of emotional functioning and psychological coping, encouraging acceptance of limitations, and developing metacognitive strategies aimed at reducing the impact of cognitive difficulties [Citation11–15]. Most of these programs were initially developed for patients with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury, and only a small number exist for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment. One reason for this might be that these patients often have normal or near-normal neuropsychological test results [Citation13] which fail to reflect their everyday difficulties (e.g., [Citation16,Citation17]). Other reasons are that clinical practice guidelines from several countries do not cover cognition, while in other countries patients either do not fall into a clearly-identified care pathway and/or fail to have their cognitive impairments identified [Citation18,Citation19]. The reasons for this are unclear, but likely include a combination of lack of organisation and interdisciplinary coordination in the post-acute care pathway as well as lack of resources for early discharge support and cognitive rehabilitation. This results in many patients being followed by clinicians who do not systematically associate their difficulties with cognitive impairment, or in patients receiving no follow-up care beyond secondary prevention. Furthermore, the notion of invisible disability is still relatively new, and patients themselves are often unable to identify the source of their difficulties and to seek help from appropriate professionals.

Despite these challenges, programs for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive and behavioural difficulties do exist (e.g., Sweden: [Citation20], Finland: [Citation21], USA: [Citation22,Citation23]). In France, until recently, treatment options for these patients were mostly limited to referrals to private practice speech therapists or neuropsychologists. In the 1980s, a 7-week (5 days/week) holistic multidisciplinary program for patients with executive dysfunction was developed at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris [Citation10]. In 2018, inspired by the success of the holistic program developed in Paris for patients with severe cognitive difficulties, a team at the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation University Hospital in Lyon, France created their own 6-week (2 days/week), outpatient program for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment after acquired brain injury. The goal of the program is to reduce functional limitations and improve participation in daily activities. The program’s initial content was based upon the clinical experience of the professionals involved in its development and delivery, as well as best practice and evidenced-based recommendations. Scientific literature and clinical resources for patients with moderate-to-severe brain injuries were consulted (e.g., [Citation9,Citation11,Citation24–26]), and content was adapted to patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment. The program’s ongoing development incorporates best clinical practice via the continued education of clinicians and the participation of clinical staff in the preparation of national-level expert consensus statements. Best research practice is ensured by the presence of PhD-trained medical staff and clinical researchers who supervise research projects piloted by medical or allied-health students or qualified clinicians. The result is a rich, but highly complex, and constantly evolving, rehabilitation program.

Treating cognitive impairment is by nature a complex undertaking, and as a consequence the field of cognitive rehabilitation research has progressed slowly. Indeed, even if two patients have similar impairment profiles, individual differences in real-life contexts mean that the impact of their deficits on everyday function will be highly variable. Another explanation for slow progress is incomplete reporting of intervention content and delivery and the difficulties this produces for discerning the effectiveness of complex programs. One way to reduce this knowledge gap is to provide a detailed description of an intervention’s content/ingredients as well as its treatment targets. This type of description is necessary in order to use appropriate tools to measure patient outcomes and to generate testable hypotheses about proposed mechanisms of action [Citation27–31]. One example of this approach is a recently-published paper by Merriman and colleagues [Citation32] that describes both the process of developing a cognition-focused psychological intervention for cognitive impairment after stroke and the intervention itself. The aim of the work described here was similar: to produce a detailed description of an outpatient cognitive rehabilitation program for chronic brain injury patients of varied aetiology (mostly stroke and TBI) and to explain the process of developing this description.

Context

The 6-week (2 days/week) program takes place in the day-hospital of a university Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation service. Eligible patients are identified as part of regular outpatient follow-up consultations conducted by a PMR doctor and are included in the program at least 1 year post injury. Most patients have mild-to-moderate deficits on some neuropsychological tests, and self-report questionnaires often reveal the presence of a subjective cognitive complaint and/or other factors like anxiety, depression, and fatigue. Patients with aphasia (revealed during the cognitive function assessment performed during the medical consultation) are not eligible for the program. Patients with mild hemiplegia or hemiparesis can participate in the program, and the occupational therapy and adapted physical activity sessions are adapted accordingly. The text Box 1 provides a general overview of the program and illustrates the cognitive and mood-state profile of those patients who had completed the program at the time of writing.

Box 1 Overview of the program offered to patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment.

Length

2 non-consecutive days per week for six weeks

6 rehabilitation programs offered by the hospital per year (September to July)

Patients

Group of 4 patients with acquired brain injury (stroke or head injury) and mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment

Physical Environment

Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Henry Gabrielle Hospital, Lyon

Day hospital: reception room, medical office, dining room and break room

Occupational Therapy Department

Adapted Physical Activity Department (one large activity room and access to an outside grassed area

Organisation

The 4 clinicians are members of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department and all of the material used in the session belongs to the Department

Patients are welcomed by the day hospital medical team who assist them with their timetable, transport, meals and any other issue or question they might have including organising appointments with other clinicians (psychologist, physical therapist, etc.)

Session structure and duration

Occupational Therapy (1 clinician)

12 group sessions (3 with neuropsychologist) – 1.5 to 2 hours

Neuropsychology (1 or 2 clinicians)

7 group sessions (3 with OT) – 1.5 hours

5 one-on-one sessions – 45 minutes

Adapted Physical Activity (1 clinician)

12 group sessions – 50 minutes

One session per week includes patients from outside the group

PMR Doctor (1 clinician)

Between 6 and 9 one-on-one sessions – 30 minutes

Figure 1. Frequency of treatment targets addressed by each clinician. Black columns represent primary treatment targets for that clinician. The program’s primary targets are: Global Psychosocial [Citation1], Temperament and Personality [Citation2], Attention [Citation5], Memory (6), Emotional [Citation8] Higher-level Cognitive [Citation10], Conversation [Citation21].

![Figure 1. Frequency of treatment targets addressed by each clinician. Black columns represent primary treatment targets for that clinician. The program’s primary targets are: Global Psychosocial [Citation1], Temperament and Personality [Citation2], Attention [Citation5], Memory (6), Emotional [Citation8] Higher-level Cognitive [Citation10], Conversation [Citation21].](/cms/asset/2dfe8b83-6a1a-4787-a3b2-d32357d881bf/idre_a_2157058_f0001_b.jpg)

Table 1. Cognitive and mood profile of patients included in the program.

Methods and results

All of the clinicians responsible for program delivery were experienced in the evaluation and treatment of patients with cognitive impairment, particularly invisible disability. They included a PMR doctor, an occupational therapist, an adapted physical activity educator, and two neuropsychologists. All of the clinicians involved in the documentation process were involved in the program’s initial design. When the program was first offered to patients (in 2018) each clinician (with the exception of one neuropsychologist) already had more than 15 years experience working with neurological patients. Program content was based on both clinical experience and evidence-based practice. All of the clinicians involved in the program’s implementation actively participated in the documentation process, which was coordinated by a neuroscience researcher.

The procedure used in this research was inspired by Poncet and colleagues [Citation10] who documented an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program for patients with executive dysfunction. Similar to Poncet et al. [Citation10], we used a method of participatory/collaborative research in which the role of the researcher evolved across time. First, she participated as an observer in the clinical team meetings and therapeutic sessions. In parallel with this observation phase she conducted a non-systematic review of the literature related to recommendations for the description and evaluation of complex rehabilitation interventions, as well as the state-of-the-art for cognitive rehabilitation programs. During this time, she engaged in regular discussions with the clinical team. After observing four 6-week programs, she organised a series of brainstorming workshops with the clinical team. The aim of these workshops was to create a detailed description of each session’s content/ingredients and therapeutic targets.

The first step in creating this description involved each clinician constructing a calendar that included a brief description of the content of each of their sessions. They then gave an informal oral presentation of their session content to the rest of the team. This helped each team member gain an overview of the program’s ingredients.

In a next step, the whole team met again to brainstorm possible ways to describe each session’s targets using vocabulary that could be shared by clinicians from different professions. Inspired by the approach used by Poncet and colleagues, who used the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF) to describe certain components of a complex rehabilitation program [Citation10, Citation15, Citation36], it was decided to use the vocabulary of the ICF [Citation37].

In the clinic, the ICF is used to facilitate thinking about an individual’s level of functioning in their everyday life, while in research it is commonly used to code study outcomes in order to facilitate comparisons across studies. Poncet and colleagues adopted the novel approach of using the ICF to describe the targets of their rehabilitation program. This approach will likely become more common as it is in line with the WHO’s efforts to create an International Classification of Health Interventions for the description of health interventions using Targets (using the ICF), Actions, and Means (https://mitel.dimi.uniud.it/ichi/).

The researcher and medical doctor first generated a list of Body Functions, Activities & Participation domains they thought were targeted by at least one clinician in at least one session. Included were any ICF domains explicitly targeted in a session (e.g., Attention: b140 & Memory: b144; OT session: Alphabetical Shopping List) or implicitly worked-on due to the nature of the session content (e.g., Attention: b140 & Memory: b144; Neuropsychologist session 1: Didactic presentation about cognitive functions and questions to patients about cognitive problems).

All team members then met four times over several months with the goal of reaching consensus concerning the team’s understanding of the various ICF domains. Since the majority of the team had little or no experience with the ICF, these meetings involved re-reading the domain descriptions as well as lengthy discussions aimed at clarifying the scope of each ICF domain. Once consensus had been reached, each professional then examined their own therapeutic sessions and, together with the researcher, identified their sessions’ treatment targets using ICF domains. shows all the second-level ICF domains targeted by at least one of the four clinicians in at least one of their sessions. A session-by-session description of the program’s content and ICF targets is included in the Annexes.

Table 2. ICF domains targeted in the program.

This program’s holistic approach is reflected by the fact that 19 of the 29 ICF domains are addressed by 3 or more professionals and these are approximately evenly distributed between Body Functions (8/15) and Activities and Participation (11/14). reveals that just over half of the treatment targets (16/29) were Global or Specific Mental Functions or Activities and Participation domains related to Learning and Applying Knowledge. This reflects the cognitive foundation of the program, which is based on the hypothesis that reducing the impact of cognitive impairment on activities and participation requires both remediation of impaired cognitive functions and compensation for these impairments. As would be expected for a holistic, multidisciplinary cognitive rehabilitation program, the program contains very diverse sessions, both in terms of content and format: presentations; evaluations; group-based cooking and sport sessions, cognitive stimulation sessions; patient-tailored one-on-one sessions (see Annexes A1 to A4). The tables in the Annexes also reveal the predominance of group-based activities in our program - more than half of the sessions include all four patients.

provides an overview of the intervention’s treatment targets but it contains no information about the "weight" of each target within a given clinician’s sessions or within the program as a whole. For example, shows that Emotional is addressed by all four clinicians, but cross-referencing this with Annexes A1 to A4 reveals that it is addressed much more often in the PMR sessions than in the OT sessions. To quantify this, we counted the number of times a target appeared in a content description and then labelled those at or above the 80th percentile as primary targets.

shows the frequency of each treatment target separately for each clinician (black bars = primary targets). The program has seven primary treatment targets (defined as primary targets for at least 2 professionals): Higher-level Cognitive [Citation10] [primary target for all four clinicians], Attention [Citation5], Memory [Citation6], and Emotional [Citation8] [primary targets for at least 3 clinicians], and Global Psychosocial [Citation1], Temperament and Personality [Citation2], and Conversation [Citation21] [primary targets for at least 2 professionals].

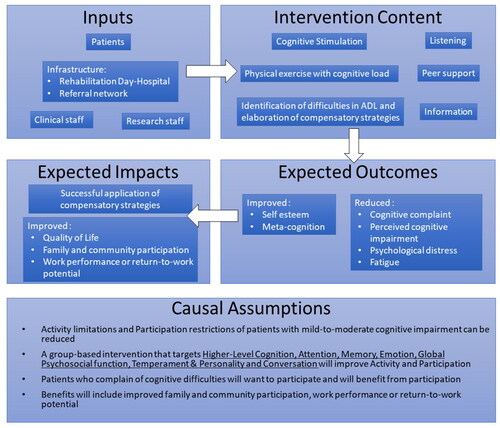

Figure 2. Logic Model of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment showing relationships between the program’s various components and outlining its causal assumptions.

Program implementation

Several clinicians reported that making the relationship between session content and therapeutic targets explicit helped them better understand their clinical assumptions and increased their confidence in their clinical skills. Despite the utility of this process for their own practice, the team agreed that it overlooked important aspects of the clinical approach deemed essential for the program’s success. For example, how/when feedback about failure and/or success is delivered. Thus, in a next step, each clinician wrote an implementation guide intended to accompany their content/treatment target tables. This level of documentation is in line with the call for rehabilitation manuals and scientific papers to include a description of each clinician’s role in the program, as this is considered to be an essential aspect of program implementation that is likely to affect program efficacy.

Similar to the ICF coding phase, the researcher met several times individually with each of the clinicians to assist them in creating the guide. The remit was to create a document that could be used to hand-over to a colleague or as a guide for a colleague in another institution thinking about creating a similar program. The emphasis was on making explicit how the professional implemented their content, what they paid attention to when conducting their session, how/when they intervened, and the content of these interventions. A template including the subheadings Roles, Objectives, Format, Observations, and Interventions was proposed to each professional but they were told that these were broad guidelines and that they could modify them and add others if necessary in order to best create their guide.

Annexes A5–A8 contain the implementation guides written by each clinician that accompany the content/treatment targets described in Annexes A1–A4. These guides describe how the clinicians use the content of their sessions to assist patients in developing or discovering compensatory strategies to reduce the negative impact of their cognitive difficulties on their everyday lives. For example, how clinicians use the situations in which they place the patients (e.g., a group cooking exercise) to help the patients to observe/understand the functional repercussions of their cognitive difficulties.

These guides reveal that while certain treatment targets are explicit and can be derived from session content, the program also has implicit therapeutic goals that emerge from analysis of program implementation rather than content. For example, all four clinicians reinforce and encourage the use of appropriate compensatory strategies and actively congratulate patients on their attempts, successes, and positive progression - acts that can be translated into a therapeutic goal of increasing self-confidence and self-esteem. Similarly, providing patients with the opportunity to become aware of their capacities as well as their difficulties and to discover the compensatory strategies that work best for them are all part of metacognitive strategy training which translates into the aim of improving metacognition or increasing metacognitive awareness.

Patients are often unaware or ignore the impact of fatigue on their cognitive performance. An important part of the program that is not immediately evident from reading the content tables and implementation guides is that the structure of the program, as well as that of certain sessions, is intended to induce fatigue (8 hour days; long cooking sessions; physically demanding APA sessions). This is done intentionally to give patients opportunities to become aware of the effects of fatigue on their cognition, mood, and performance, and for clinicians to give them supportive feedback to help increase their awareness and understanding of the consequences of fatigue. This awareness-raising is accompanied by brainstorming about strategies that could be used to reduce fatigue.

Another aspect of the program that is also not immediately obvious from reading the content tables or intervention guides is the importance of the group itself. The peer support provided by bringing together four people with similar cognitive complaints and giving them the opportunity to try out new strategies and to share their difficulties reduces the psychological distress that is so often expressed by these patients. When analysed as a whole, these implicit therapeutic goals can be considered as subcomponents of a more global therapeutic goal, which is to reduce the impact of cognitive difficulties on everyday functioning, something that can be operationalised by a reduction in subjective cognitive complaint.

We finalised the documentation process by creating a simple logic model. To do this, we used the material generated throughout the process to make explicit the program’s expected outcome and impacts as well as its underlying causal assumptions ().

Discussion

Human and physical resources as well as the clinical experience and soft skills of each team differ widely from one clinical setting to another. Thus, it is impossible for rehabilitation teams to produce exact replicates of holistic rehabilitation programs. This slows down research into program efficacy and hampers development of the discipline of rehabilitation science. One way of overcoming this is to provide detailed program descriptions that include treatment targets which can be used to guide clinicians who want to create similar programs. Indeed, we engaged in this documentation process because we hypothesise that programs that differ in terms of content/ingredients/clinical personnel can provide similar benefits for patients if they share similar treatment targets.

This study is one of the first to approach intervention description from the perspective of the ICF and, to our knowledge, the first to provide an ICF-based description of the therapeutic targets of an entire holistic, cognitive remediation program for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment. Our method was based on that used by Poncet and colleagues [Citation10] who used it to describe a holistic program for patients with executive dysfunction but only published data on the ICF targets of their cooking activity sessions. Despite targeting different patient populations, a comparison of the two cooking session descriptions revealed considerable overlap in ICF domains identified as targeted by the cooking activities in each program.

Interestingly, however, while we identified a total of 27 treatment targets for our entire program, Poncet and colleagues identified more than 50 for their cooking activity alone. The main explanation for this appears to be that they included numerous domains that were present in our intervention, but which we considered to be too frequently (or too rarely) engaged for their inclusion to add any useful information regarding treatment targets. Some examples include: Perceptual functions: Specific mental functions of recognizing and interpreting sensory stimuli (b156) and Reading: Performing activities involved in the comprehension and interpretation of written language (d166).

This difference highlights the difficulty of using the ICF approach to document complex cognitive rehabilitation interventions, where treatment targets are far more difficult to identify than, for example, a surgical intervention that targets muscles in the forearm (Structure of Upper Extremity- s730). It also raises the question of how consensus can be reached regarding what is targeted by a treatment, and the level of detail that should be included in an intervention description. For example, it would appear that Poncet and colleagues adopted an exhaustive approach, including ICF domain codes for all of the domains engaged during a therapeutic session. In contrast, we chose to document only those domains considered essential targets for program success. While the former approach is without a doubt more complete, it provides the reader with no information about key/active ingredients or essential targets. Our “condensed” approach, however, could have biased the documentation process and resulted in a Table of ICF domains that reflects our team’s clinical hypotheses regarding essential (active) ingredients rather than all of the program’s treatment targets.

Some of our program’s content aims to remediate individual cognitive functions using learning-based remediation approaches. For example, each APA session builds upon tasks learnt in the previous sessions, with the idea that gradually learning a number of distinct tasks and automating their performance will enable patients to efficiently perform highly complex tasks. The APA sessions are also based upon spaced practice and cognitive trial-and-error methods, whereby patients are confronted with slightly different situations once a week and are encouraged to try a range of different strategies until they eventually find one that works. This approach is based upon the hypothesis that successful strategies discovered under trial-and-error conditions will lead to reinforcement-based learning. In the Occupational Therapy sessions, patients also learn deep encoding techniques, which are helpful for retaining and understanding new information. For example, by using semantic- or personalised meaning- based processing, patients are shown how to create links between new material and their own ideas, emotions, or existing knowledge-base, with the idea that this will make them more efficient at retaining and recalling the new material.

The majority of our program’s content is designed to compensate for impaired cognitive function by improving metacognitive awareness and providing metacognitive strategy training. These approaches are particularly well adapted to difficulties with planning, organisation, and focusing attention (executive functions), as patients can learn to recognize their own cognitive capacities and impairments, identify where and when these impairments have the greatest impact on their activities and participation, and put in place strategies to limit this impact. Interestingly, some authors class metacognitive strategy learning as a remediation rather than a compensatory technique (see for example [Citation38]). Even though it targets the modification of certain cognitive functions, we do not consider that this approach restores these cognitive functions. Rather, our program is based on the hypothesis that by teaching patients to identify their cognitive problems, applying compensatory strategies, and modifying their environment, it is possible to remediate cognitive impairments without restoring impaired cognitive functions [Citation12].

Compliance with practice standards

Current best-practice, evidence-based guidelines for the content of rehabilitation interventions for patients with cognitive deficits lack precision, and most of the evidence comes from studies with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury patients. Despite this, our rehabilitation program contains many aspects that comply with recommendations outlined by the Cognitive Rehabilitation Task Force (see Cicerone et al. [Citation25]).

Cicerone and colleagues [Citation25] provide four recommendations for comprehensive-holistic neuropsychological rehabilitation programs. As a practice standard, they recommend provision of post-acute, comprehensive-holistic neuropsychological rehabilitation for both traumatic and non-traumatic brain injuries irrespective of severity or time post injury. Our 6-week, holistic cognitive rehabilitation program offered to patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment at least 1 year post-injury is in line with this recommendation. A practice guideline recommends that these programs include “computer-assisted cognitive retraining with the involvement and direction of a rehabilitation therapist” ([Citation25], p. 13). The one-on-one sessions with the PMR physician include computer-based exercises. While training time is insufficient for us to claim that these exercises contribute to the remediation of impaired cognitive functions, they are essential for increasing metacognitive awareness and teaching metacognition-based compensation strategies (i.e., reduce task speed or difficulty with the aim of achieving a high level of accuracy).

Further recommendations (practice options) are that holistic programs should promote occupational functioning and include both group and individualised interventions, with the latter being based on personalised goal-setting. Our current program contains almost all of these elements, and we are working towards implementing the goal-setting aspect of this practice option by identifying personalised goals at the beginning of the program using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Our long-term goal is to establish expected levels of achievement for two or three personalised goals, and to use Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) scores at 3 and 6 months post-program as an outcome measure of the program’s effect on Activities and Participation.

Our program is not completely aligned with practice recommendations for treatment of attention deficits, which include the provision of both intensive direct attention training and metacognitive strategy training (practice standard), as well as modular direct attention training for specific working memory impairments (practice guideline). We do not currently have the resources to add intensive direct attention training to our program, but we are aware that its inclusion could be beneficial for some patients.

Our program is aligned with recommended practice for the treatment of memory deficits, which includes memory strategy training aimed at improving recall and prospective memory (practice standard) and the inclusion of group-based interventions (practice option). Indeed, our occupational therapy sessions include numerous group-based activities that focus on memory training (e.g., Kim’s game, shopping list, and remember a name for a face exercises). These are complemented by the group-based APA sessions, in which patients are encouraged to analyse their failures (e.g., forgetting a person’s name or throwing the ball to the wrong person) and to use this analysis to develop more efficient strategies.

The speech therapists in our hospital have recently developed new program content that is designed to address communication deficits after TBI. This content is aligned with recommended practice for the improvement of social-communication skills in this population, as it provides a group-based intervention that focusses on pragmatic conversational skills and emotion regulation. To date, these sessions have only been proposed to one group of TBI patients.

Patients are included in our program > 1 year post brain lesion, when the potential benefits of training-based remediation of impaired cognitive functions are small. This is one reason that metacognitive strategy training is at the core of our program. Another reason is that many patients have normal (or near-normal) results on standardardised neuropsychological tests of specific cognitive functions, but they report considerable cognitive impairment during complex, everyday situations, particularly when these involve time- or performance-constraints.

The recommended practice standard for the treatment of executive function deficits is metacognitive strategy training (self-monitoring and self-regulation) implemented in the context of personalised practical goals and functional skills (practice guideline). While our program broadly adheres to these recommendations, it does not include protocolised self-awareness training (see Shum et al. [Citation39] for an example). Instead, as can be seen in the clinical intervention descriptions provided in the implementation guides, self-awareness training provides the background for the whole program. It is possible, however, that some patients might benefit from more formal, protocol-based self-awareness training.

While the content tables and intervention guides provide a thorough overview of delivery of a typical program, it is important to emphasise that one of the guiding principles of our program is adjustment to each patient’s needs. This is put into practice by conducting clinical interviews with each patient at the beginning of the program (independent interviews are conducted by the PMR doctor and neuropsychologist), the aim of which is to gain a better understanding of difficulties, preferences, and goals, in order to adjust the content of one-on-one sessions. Another, less tangible, way in which the program is tailored to each individual is the way in which each professional adjusts their interventions and what they pay attention to during each session. For example, if a patient has expressed anger and/or frustration about being constantly reminded of their attentional lapses, the Occupational Therapist might choose to ignore their attentional errors and instead focus on providing positive feedback related to effective communication with other group members under conditions of time pressure. In contrast, if another patient asked to be alerted when they wander off task, she might focus on their attentional errors, and provide detailed feedback about the conditions under which the patient seems most prone to make attentional errors (noisy room, multiple task demands, time constraints, etc).

Compliance with complex intervention reporting

One of our goals was to provide a description coherent with current recommendations for rehabilitation intervention reporting, and our documentation is in line with the conceptual framework of the Rehabilitation Treatment Taxonomy, now known as the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System (RTSS Citation30,Citation31,Citation40,Citation41), which recommends descriptions in terms of Ingredients and Treatment Targets. We also provide sufficient information to complete the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) [Citation28]. Furthermore, our use of the ICF taxonomy to identify treatment targets is in line with the International Classification of Health Interventions (https://mitel.dimi.uniud.it/ichi/) currently being developed by the WHO, which provides a taxonomy for describing health interventions in terms of Targets (ICF domains), Actions, and Means.

Identifying essential ingredients

Identifying whether an ingredient is active or inactive, and whether certain active ingredients effect a change in treatment targets is another issue of importance for complex rehabilitation programs [Citation40]. We did not set out to identify which ingredients in our program can be classified as essential, but we can make several hypotheses. First, we hypothesise that the content of our program that aligns with the practice standards identified by Cicerone and colleagues [Citation25] represents essential ingredients. We also hypothesise that the group is an essential ingredient; feedback from patients suggests that sharing with others who have similar difficulties or challenges is an important part of the therapeutic effect of the program. The social context provided by the group increases enjoyment and motivation, and spending time with people who have similar problems can decrease isolation and psychological distress and might also be important for learning new compensatory strategies [Citation42]. The group format also gives patients the opportunity to listen to others with similar issues, which could be important for increasing self-awareness and metacognition. By increasing awareness of cognitive strengths and weakness, including gaining a better understanding of which situations might be difficult and which environments enhance or decrease cognitive performance, patients can learn new strategies and adapt their behaviour and their environment in order to minimise functional limitations and improve participation in daily activities.

We further hypothesise that the interdisciplinary clinical team is an essential ingredient. The different contexts in which the various clinicians see the patient provide a variety of viewpoints, which allow the team to have a more realistic picture of each patient’s strengths and challenges and how these are modified by the environment. Furthermore, since it is essential to provide patients with a structured, secure environment in which they can observe, analyse and receive feedback about the effects of their cognitive impairments we suggest that the semi-ecological situations are essential to help patients to better understand the effects of their impairments on their everyday lives and to develop strategies that they can put in place outside the program’s setting, with the intention that this transfer to everyday situations will lead to long-term improvement in their quality of life.

Conclusion and perspectives

This paper describes an interdisciplinary, holistic, cognitive rehabilitation program for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment and the process involved in creating this description. The documentation process would not have been possible without the presence of an external observer (in this case a researcher) who had the time to observe and participate in the program over more than one year. This was essential for building a solid, trusting relationship between her and the clinicians, a relationship that was crucial for the success of the documentation process which necessitated clinicians verbalising their decision-making methods and clinical reasoning.

The role of coordinating the description process was held by a neuroscience researcher, and while her researcher status was not essential for the task, it did require a skill-set drawn from a background in research. Our team found the researcher-clinician collaboration to be particularly rich, and several clinicians reported that this process helped them to better understand and thereby improve their own practice. It is important to note, however, that this type of documentation process requires a large time investment (each member of our clinical team contributed approximately 30 h to discussions and documentation) as well as a willingness to become familiar with the ICF.

The explicit treatment targets identified using the ICF domain codes and the implicit therapeutic goals identified from the implementation guides are aligned with the objective of our holistic rehabilitation program, which is to reduce the impact of cognitive difficulties on everyday functioning. We currently measure this outcome using a questionnaire of subjective cognitive complaint. Now that we have clearly identified the program's treatment targets our next goal is to refine the tools currently used to evaluate these targets in order to investigate whether the program induces long-term changes that reduce functional limitations and improve participation in activities of daily life as well as overall quality of life. We are working towards implementing personalised goal setting at the start of the program and assessment of goal achievement at 3 and 6 months post-program. In addition to providing an objective outcome measure of the program’s efficacy, we hypothesise that the inclusion of individually-tailored goals will increase motivation and engagement in the program. Similar to the psychological intervention described by Merriman and colleagues [Citation32], in the future we plan to include caregivers in the program, introduce more home-based activities to optimise the application of new strategies to real life situations, and develop a personalisable booklet containing information and links to useful resources.

Our ambition in writing this program description is that it will be useful for other clinicians wanting to establish a similar program but also that our description of the process will be useful to those teams ready to take on the challenge of describing and evaluating complex rehabilitation programs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (67.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jacques Luauté for his helpful comments on the manuscript as well as Damien Nivesse and Anne-Laure Charlois for their dedication to advancing rehabilitation research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723–1731.

- Langhorne P, Ramachandra S, Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD000197.

- Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(9):1288–1294.

- King NS, Kirwilliam S. Permanent post-concussion symptoms after mild head injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25(5):462–470.

- Moran GM, Fletcher B, Feltham MG, et al. Fatigue, psychological and cognitive impairment following transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(10):1258–1267.

- Muus I, Petzold M, Ringsberg KC. Health-related quality of life among danish patients 3 and 12 months after TIA or mild stroke. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(2):211–218.

- Ben-Yishay Y, Diller L. Cognitive remediation in traumatic brain injury: update and issues. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74(2):204–213.

- Christensen AL, Teasdale T. A clinically and neurophysiologically led postacute rehabilitation programme. In: Chamberlain MA, Neumann V, Tennant A, editors. Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: services, treatments and outcomes [internet]. Boston (MA): springer US; 1995. p. 88–98. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2871-9_8

- Cicerone KD, Dahlberg C, Kalmar K, et al. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: recommendations for clinical practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(12):1596–1615.

- Poncet F, Swaine B, Pradat-Diehl P. Documenter un programme de réadaptation en référence au modèle logique théorique : un atout dans la démarche évaluative. Sante Publique. 2017;29(1):7–19.

- Prigatano GP. Principles of neuropsychological rehabilitation. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 356.

- Wilson BA, editor. Neuropsychological rehabilitation: theory and practice. Exton (PA): Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers; 2005. p. 309.

- Fleeman JA, Stavisky C, Carson S, et al. Integrating cognitive rehabilitation: a preliminary program description and theoretical review of an interdisciplinary cognitive rehabilitation program. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;37(3):471–486.

- Institute of Medicine. Cognitive rehabilitation therapy for traumatic brain injury: evaluating the evidence [internet]. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2011. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13220/cognitive-rehabilitation-therapy-for-traumatic-brain-injury-evaluating-the-evidence

- Poncet F. Exploration des effets d’un programme de réadaptation visant l’amélioration des activités et la participation des personnes cérébrolésées: application à l’activité cuisine [PhD Thesis]. Paris, 2014.

- Eslinger PJ, Damasio AR. Severe disturbance of higher cognition after bilateral frontal lobe ablation: patient EVR. Neurology. 1985;35(12):1731–1741.

- Shallice T, Burgess PW. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114(2):727–741.

- McMahon D, Micallef C, Quinn TJ. Review of clinical practice guidelines relating to cognitive assessment in stroke. Disab Rehabil. 2022;44;(24):7632–7640.

- Adamit T, Maeir A, Ben Assayag E, et al. Impact of first-ever mild stroke on participation at 3 and 6 month post-event: the Tabasco study. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(8):667–673.

- Lundqvist A, Linnros H, Orlenius H, et al. Improved self-awareness and coping strategies for patients with acquired brain injury—a group therapy programme. Brain Inj. 2010;24(6):823–832.

- Sarajuuri JM, Kaipio ML, Koskinen SK, et al. Outcome of a comprehensive neurorehabilitation program for patients with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12):2296–2302.

- Tiersky LA, Anselmi V, Johnston MV, et al. A trial of neuropsychologic rehabilitation in Mild-Spectrum traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1565–1574.

- Twamley EW, Thomas KR, Gregory AM, et al. CogSMART compensatory cognitive training for traumatic brain injury: effects over 1 year. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(6):391–401.

- Cicerone KD, Langenbahn DM, Braden C, et al. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(4):519–530.

- Cicerone KD, Goldin Y, Ganci K, et al. Evidence-Based cognitive rehabilitation: systematic review of the literature from 2009 through 2014. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(8):1515–1533.

- Wilson BA. Neuropsychological rehabilitation: theory, models, therapy and outcome [internet]. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10333233

- Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT NPT Group, et al. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40–47.

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

- Van Stan JH, Dijkers MP, Whyte J, et al. The rehabilitation treatment specification system: implications for improvements in research design, reporting, replication, and synthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(1):146–155.

- Van Stan JH, Whyte J, Duffy JR, et al. Rehabilitation treatment specification system: methodology to identify and describe unique targets and ingredients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(3):521–531.

- Whyte J, Hart T, Dijkers M, et al. Creating a manual to better define rehabilitation treatments [internet]. Washington (DC): Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.25302/02.2020.ME.140314083

- Merriman N, Gillan D, Pender N, et al. The StrokeCog study: development and description of a cognition-focused psychological intervention to address cognitive impairment following stroke. Psychol Health. 2021;36(7):792–809.

- Van Dyk KV, Crespi CM, Petersen L, et al. Identifying Cancer-Related cognitive impairment using the FACT-Cog perceived cognitive impairment. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(1):pkz099.

- Lange M, Heutte N, Morel N, et al. Cognitive complaints in cancer: the french version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy–cognitive function (FACT-Cog), normative data from a healthy population. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2016;26(3):392–409.

- Wagner LI, Sweet J, Butt Z, et al. Measuring patient Self-Reported cognitive function: development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy–cognitive function instrument. J Support Oncol. 2009;7(6):8.

- Poncet F, Swaine B, Migeot H, et al. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for persons with acquired brain injury and executive dysfunction. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(13):1569–1583.

- World Health Organization. ICF: international classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. p. 299.

- Stephens JA, Williamson KNC, Berryhill ME. Evidence – based practice for traumatic brain injury a cognitive rehabilitation reference for occupational therapists. OTJR. 2015;35(1):5–22.

- Shum D, Fleming J, Gill H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prospective memory rehabilitation in adults with traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(3):216–223.

- Hart T, Tsaousides T, Zanca JM, et al. Toward a Theory-Driven classification of rehabilitation treatments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(1 Suppl):S33–S44.e2.

- Whyte J, Dijkers MP, Hart T, et al. Development of a Theory-Driven rehabilitation treatment taxonomy: Conceptual issues. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(1 Suppl):S24–S32.e2.

- Hammond FM, Barrett R, Dijkers MP, et al. Group therapy use and its impact on the outcomes of inpatient rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: data from TBI-PBE project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(8 Suppl):S282–S292.e5.