Abstract

Purpose

User participation is important in the delivery of health- and social services. Yet, our knowledge regarding how user participation is experienced from the perspective of those who use these services is limited. This study aims to develop knowledge regarding how young persons living with disabilities experience becoming independent in user participation.

Materials and methods

This qualitative study is inspired by Constructivist Grounded Theory. Nine young persons between 16 and 25 years of age and living with a disability, participated in the interviews.

Results

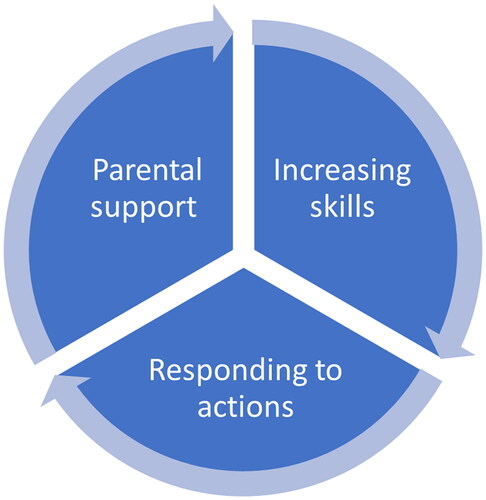

The results revealed that user participation for young persons is a socially situated, relational, and skills-dependent process. User participation is characterized as a process, consisting of increasing skills, gradually reducing parental support, and responding to interactions with professionals. The three categories are strongly reciprocal and interrelated, forming the unifying core category of Striving towards independence in user participation.

Conclusion

We theorize about the Interrelated process of becoming independent in user participation for young persons with disabilities. This theory highlights the need to understand the interrelatedness of user participation, allowing for a recognition of the complexity of user participation, showing it as a process involving developing skills, and gradually becoming independent and skilled in user participation.

Young persons with disability rely on support from parents as well as professionals to become independent in user participation

Professionals should acknowledge that user participation is a learning process and allow for time and resources to aid this process

Focusing on increasing health literacy alone is not sufficient to ensure user participation for young persons with disability

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Participation in service delivery is an important aspect of health- and social care services and the collaborative practice between services and its users [Citation1]. Including service users in the process of their care opens for treatment better suited for the individual [Citation1]. Yet, we have limited knowledge of how service users experience user participation, especially from the perspective of young persons living with a disability or chronic disease. There is also limited knowledge highlighting the complexities of the skills and competencies that are required to be able to participate [Citation2–4]. In this paper, we focus on developing knowledge regarding the process of becoming able to independently take part in user participation as experienced by young persons living with a disability during their transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Transition process and user participation

Stewart et al.’s [Citation5] study of the transition from adolescence to adulthood for young persons with disabilities revealed that a combination of complexities occurred in the interaction between person and environment throughout the process of transitions. They identified that transitioning required a complex collaboration between the professionals, parents, and the young persons’ themselves. To add to the complexity of the transition process, changing from services for children to services for adults requires a need for re-establishing collaboration with services [Citation6]. We know little of how the complexities of this transition process affect young persons’ user participation and engagement with services.

Different perspectives on user participation

Eide et al. [Citation7] point out that user participation can be seen both as a tool for producing more effective services and through a more idealistic lens: peoples’ rights to influence on matters relevant to themselves. Participation is also perceived as an end goal for health care [Citation7]. Hemmingsson and Söderström [Citation8] state that participation is “dynamic, flexible and relational” (p. 180). According to Imms et al. [Citation4] participation as a construct can be understood as both a process and an outcome, seeing participation as a complex and multidimensional construct. It is therefore necessary to clarify how participation is delimited in this paper. Eide et al. [Citation7] point out that there is a “blurred distinction” between participation as in engaging with services and participation in daily life (p. 6). Therefore, this paper follows Eide et al.’s suggestion of separating the two. Hence, participation is here understood as a process of engaging with professionals working in services in order to take an active part in decision-making regarding ones’ own health- and social care.

Participation in relation to services, in this paper termed user participation, is complex and multifaceted [Citation9,Citation10], and a vaguely defined concept [Citation11]. It is necessary to acknowledge participation as contextually related [Citation4]. Kvam et al. [Citation12] point out that participation in relation to services is intertwined with several other aspects, such as environmental, health, and personal factors (p. 100). Additionally, it is a concept that tends to be understood in different ways by different persons and professions [Citation7]. McCormack et al. [Citation13] suggested that participation is not limited to what individuals must do to receive care, but also two-way interactions between patients, their next of kin, and the professionals in the health care system. This makes user participation a process of engaging with systems and the persons working in the systems regarding individual needs. However, this definition does not give any directions as to how user participation unfolds. Hence, definitions and conceptualisations of user participation and engagement vary [Citation13].

Participation in health- and social care services is typically divided in two levels: system and individual participation. User participation on a system level involves systematic and political work related to service delivery, through the representation of selected patient groups or patient organisations [Citation14]. At the individual level, participation is ensured through engaging individuals in the services they receive, ensuring they have the opportunity to vocalize their needs and take part in decision-making [Citation15,Citation16]. Consequently, user participation at the individual level depends on peoples’ abilities to make their needs explicit [Citation9], necessitating a level of independence. Independence in this situation refers to a dynamic process where there is congruence between personal performance and abilities, and the contextual expectations of the situation [Citation17]. As previous research has found, young persons living with disabilities are expected to manage user participation independently as they enter services for adult people [Citation6].

In Norway, user participation is characterised by co-production. Persons receiving services are viewed as competent citizens and thus have a right to, and are expected to, contribute to services concerning them. The aim is to empower service recipients to take part in co-producing services. However, it entails placing control and responsibility with the service recipients [Citation15]. This makes participation more than only a right. Askheim points to an [Citation15] explicit aspect of duty. To receive help and support, service users have a duty to fulfil demands set on them by the health- and social care services. Naturally, this requires skills and competencies. Further studies into the process of participation are necessary to increase our knowledge about the reciprocal nature of user participation, skills, relations, and social aspects. For this study, we focus on user participation on an individual level, as a co-production between the young persons living with a disability and the services they are involved with.

Previous research on user participation

Previous research regarding user participation in health- and social care has focused on identifying environmental factors that hinder participation, identifying perceived attitudes among staff and communication as important factors, alongside accessible equipment [Citation18]. Johannesen et al. [Citation19] study showed that although professionals perceived user participation as important, there was a gap between the importance of user participation on a policy level and the professionals’ opportunities to comply with the expected level of user participation. Participation in its ideal form is not achievable unless adequate time is set aside to build relationships and shared knowledge [Citation6,Citation9].

Research shows that young persons want to have a say regarding services aimed at them [Citation6,Citation20]. Previous research regarding user participation in health care for young people indicate that user participation required respectful relations with professionals and competent professionals [Citation20, Citation21], shared decision-making [Citation22] and age-adequate settings [Citation23]. A study by Skagestad et al. [Citation24] identified the importance of equal and complimentary status between youth and professionals, showing that a lack of this could affect the ability and effort to participate. Bjønnes et al.’s [Citation25] study from the staff’s perspectives of user participation for adolescents highlights the importance of individualised therapy and access to decision-making, as well as relational factors such as time and safety. Jager et al. [Citation26] found that flexibility in communication style to meet individual needs was important.

User participation’s relation to other concepts

Participation is related to several other concepts, such as empowerment and client-centredness [Citation27], health literacy [Citation10], and relations with professionals [Citation9]. Thus, it can be challenging to separate user participation as a concept from its related concepts. Angel and Fredriksen [Citation9] point out how user participation is known under several other names such as engagement and involvement. Previous research by Imms et al. [Citation3] have highlighted the need to develop conceptual clarity regarding participation, increasing the concepts’ operationalisation. This is especially relevant for furthering the understanding of the concept, which is necessary to delimit user participation and to understand its relatedness to other concepts. Especially interesting is health literacy (HL) and its relation to user participation. With its focus is on increasing a persons’ capacity to participate in decision-making [Citation28], this is an area that needs further attention with regard to its connection to user participation. Castro [Citation27] recognised patient participation as interrelated with other concepts, such as patient-centeredness and empowerment. Castro et al. [Citation27], Imms et al. [Citation3,Citation4] and Angel and Fredriksen [Citation9] research shows why it is challenging to make overall definitions of user participation and descriptions of how user participation unfolds. Acknowledging this complexity, this paper perceives user participation as a concept that encompass the above-mentioned concepts in a complex, interrelated process.

Aim

The aim of this study is to develop knowledge regarding the complexity of user participation and its related concepts as experienced by young persons with disabilities. Our study explores user participation from the view of young persons, aiming to produce knowledge that can go towards distinguishing different parts of the process that leads to independence in participation with services. We focus on understanding user participation as a process that is developed over time, through the acquisition of skills and support from parents and professionals. Focusing on developing knowledge regarding the complexity of user participation, we aim to clarify how relational aspects, such as the development of health literacy skills, the process of becoming independent from parental support, and responses from professionals affect user participation for young persons with disabilities.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study follows a qualitative design. The data generation and analysis are inspired by Charmaz’ [Citation29] Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT). This method was chosen due to its usefulness in exploring processes as well as its focus on developing theory grounded in data. The study is approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), with reference number 865327.

Participants

This study is based on interviews with young persons between the ages of 16 and 25, living with a disability or a chronic disease, who were regularly in contact with health- and social care services (). The participants were recruited via healthcare services and interest organisations, through the selection of healthcare professionals or self-recruitment via social media, respectively. The health care professionals provided information to possible participants, leaving it up to the person themselves to initiate contact with the first author. The interest organisations operated with a wider approach, spreading information regarding the study on their social media sites. The participants lived with a range of disabilities or illnesses, ranging from chronic fatigue, congenital conditions, sensory impairment to neurological conditions affecting mobility. As a result of the recruiting method, the sample consists of participants who identified themselves as living with a disability or a chronic disease that affected them in their lives. By using this approach, we believe to have ensured the participation of young persons based on their wish to partake in studies. Due to young persons living with disabilities being a small population, we have taken extra care in not providing more details regarding the participants to protect their identity.

Table 1. Participants.

A total of nine young persons, eight females, and one male, were interviewed once and four were selected for further participation, involving a second interview between six and twelve months after the first. The study was designed to follow up participants who were in the phase of transitioning (approx. 16–19 years), meaning that criteria for further participation were based on the age of the person at the time of the interview and their willingness and consent for further participation.

Data construction

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews. The participants were encouraged to select a place to meet where they felt safe to talk. They were also offered the opportunity to bring a parent to sit with them during the interview. Most of the interviews took place in the participants homes. For those who decided to meet elsewhere, the first author booked meeting rooms in public buildings (e.g., local hospitals). The first author performed the interviews and made sure the interviews were conducted in safe surroundings allowing for privacy and anonymity, in line with research ethics. None of the participants chose to have parents present during the interviews, however, some had their parents nearby in case they needed them.

The participants were asked open-ended questions regarding experiences of participation in relation to health- and social care professionals and encouraged to share stories about how participation occurred. Follow-up questions ensured detailed descriptions of the experiences and necessary clarifications. Typical follow-up questions were “who were involved”, “can you tell me more about what happened next” and “how did you feel about that”. Additionally, the participants were asked questions regarding the use of professional jargon, their understanding of how to navigate the system, and their response to how they were being met by professionals.

In line with CGT, the data collection is designed to follow up codes that crystallise during the initial data analysis [Citation29]. From the fourth interview, the questions became increasingly focused, in line with theoretical sampling. The follow-up interviews were based on theoretical sampling entirely, to explicate categories developed from analysing the initial interviews [Citation29]. Categories regarding user participation and skills required to participate emerged early in the data generation and analysis. Using CGT throughout the process allowed for an increased understanding and refinement of categories and concepts that emerged from the data.

Analysis

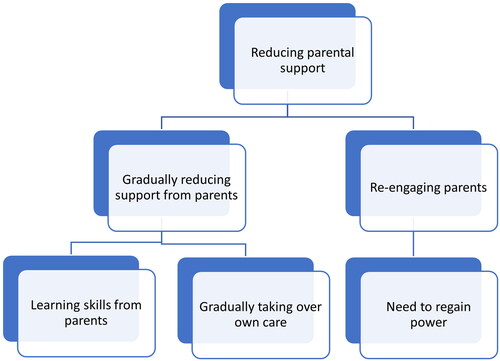

The data was analysed drawing on Charmaz’ CGT [Citation29]. The process of analysis occurred simultaneously with the data collection. Following the interview, data was transcribed and initially analysed. Both authors participated in the process, discussing codes and categories. Codes were grouped in tentative categories, eventually building up to the categories presented in this paper. An example of the process can be seen in , where tentative categories building up to the category of reducing parental support is illustrated. During the process, memos regarding emerging codes were written. This aided the process of focused coding, making the codes more explicit and turning them into categories. The process of simultaneously collecting and analysing data allowed for theoretical sampling, and by constant comparison of codes, we developed emerging categories.

Figure 1. Tentative categories building up to the category reducing parental support.

Before theorizing how we can understand the process of becoming independent in user participation, we analysed the categories, based on the technique of axial coding as described in Charmaz [Citation29], to learn more about the dynamics within and between the categories. This phase required abductive reasoning. Charmaz [Citation29] describes abductive reasoning as the process of examining inductive data and observing that the data cannot be explained using existing theory alone. Thus, we searched existing theoretical explanations, not finding a sufficient existing theoretical explanation, we theorised other plausible explanations, creating a new theory combining existing theories to form a novel understanding. Through this analytical process, it became clear that the data could add novel understanding to existing theories of user participation, allowing us to theorize on how becoming independent in user participation is an interrelational process.

Reflexivity

Researchers’ preconceptions have influence throughout the research process [Citation29]. The authors of this paper have backgrounds from academia, and as occupational therapist and physiotherapist, respectively. Both authors have worked with young persons with disabilities. The need to deepen the understanding regarding young person’s experiences of user participation as a process requires a reflective approach examining own preconceptions. Reflexivity was ensured using reflective memos, and discussions between the authors.

Results

The findings suggest that user participation is a socially situated, relational, and skills-dependent process. The different aspects of the process are dependent of each other, forming reciprocal relationships. Further, the young persons’ experiences of user participation were characterized by being in a process of skills progression, striving towards independence. Thus, the unifying core category of Striving towards independence in user participation was developed.

The core category consists of three categories. The first, Increasing skills, depict how user participation consists of individual focus on learning to effectively communicate, navigate health- and social services, and increasingly take on more and more responsibilities for one’s own health and care. The second category, Gradually reducing parental support, shows how young persons’ go through a life-phase-relevant process of becoming independent from parental support. Yet they linger on a verge of dependency, at times requiring support to attain power and regain agency, even after the age of eighteen due to the complexities of their life situations. The third category, Responding to interaction with professionals, highlights the importance supportive relations with health care professionals and social workers has for young persons’ agency and for the development of necessary individual skills to participate in their own health- and social care. The three categories are strongly reciprocal, suggesting a high level of interrelatedness.

Increasing skills

The analysis showed that the young persons described user participation as a phenomenon that required going through a learning process increasing one’s skills and abilities to communicate, understand information, navigate complex systems, and express needs. Participation was difficult to achieve without increasing these skills.

Una spoke of how she had learned to express herself in a factual manner, stating “writing factual emails, having factual conversations on the phone, that has gone well”. During the first interview, she described how she had had to learn to express her needs clearly, founding her explanations of her needs with examples from her life. By doing so, she found that her experience of participation increased.

Malena shared similar experiences. However, she experienced having to be on guard regarding how she expressed her needs to professionals. She had several similar experiences from different parts of the health- and social care system, but particularly one episode stood out when she spoke about this topic. This was related to the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV).

At NAV perhaps. It is a bit of a different setting there, you sort of have to be a bit, you can’t say ‘no I am a bit tired at times’, you can’t say that. [laughs]. Right, you have to tell it like it is ‘I am tired all the time, I have to sleep so and so much, I have to rest this and this much’. That’s how you got to say it to them. If not then they don’t understand it.

These two quotes exemplify the need for young persons to learn to express themselves independently, using more formal language, being specific and to the point, reducing the risk of misunderstandings.

Another aspect of increasing skills entailed learning to understand professional jargon and the complexities of the health- and social care system. This was necessary to comprehend some of the information they were given. Emily explained how she, during a consultation with a doctor, were told she required a form of special glasses to prevent further damage to her eyes. She explained:

He kept talking about me needing to go and see an optometrist, and I really did not understand what he was talking about. Is he not an optometrist then? Then I realised he was talking about an optician and I understood that he was telling me to get a normal appointment for new computer glasses.

Gradually reducing parental support

Becoming a fully participating patient or service user was a skill that the young persons learned from their parents. The data shows that this was a process of gradually reducing support from parents and that the level of satisfaction with how well one could participate was affected by the support they got from their parents. Additionally, the results show that the young persons used their parents consciously to regain power in situations where they felt dissatisfied with the level of user participation.

The participants’ stories shared many similarities. They all spoke of user participation as a process they learned from their parents. Emily explained that her mother had gradually given her more and more autonomy in participating in her own care. “She [mother] has been like this from when I was sixteen-seventeen years that I had to do it, starting practicing, starting to call the doctor”. She explained how the process had consisted of steps, where her mother had attended appointments with her, but reduced her input and let Emily take charge and describe her situation. Then she had progressed into letting Emily attend the appointments herself while her mother sat in the waiting area. That way she was available if needed. The next step was being available at home after the appointment for Emily to discuss things, and finally, where she was currently at as eighteen years old, she managed on her own.

Lilly, who was 24 at the age of her interview, did not receive support from her mother when engaging with services after turning eighteen. For her, other significant adults she trusted became important for this process. Finding participating with services challenging, she stated:

Everything has been extremely complicated. Especially after I had to do things myself. […] the resource persons I have around me, who despite me being a legal

Due to the complexity of the life of young persons, caused not only by their ongoing need for support from public services but also caused by several changes in their lives, such as going through the educational system, moving from home, and getting employed, they needed the support to increase and decrease depending on the situation. Moving from home often meant changing health care professionals. This did for some of the participants mean they needed the assistance of their parents again despite being previously independent in participation. This shows that the process of gradually reducing parental support was not a linear process.

Responding to interactions with professionals

According to the results, interactions with professionals impacted the degree of participation. Experiences of successful participation were related to professionals who were described as approachable. Contrary, unsuccessful participation was affected by a perceived lack of interest and interaction from the professionals.

The young persons described experiences where professionals were perceived as approachable as situations where they were more likely to participate. Natalie described how she had struggled getting her message across to professionals when they did not show clear signs of interest and approachability. She described how small things like eye contact made it easier to participate. “If they are a bit like, not very nice, or a bit, if they are difficult to talk with or stuff like that, then I say less”. When asked to elaborate she stated:

No, I don’t know, it’s a bit more like… How you appear, right. And if you, sort of, greet [people] with a smile and say hi and stuff. Or if you’re just like ‘oh, another patient’.

Lilly had several experiences of not being heard or acknowledged in meetings with professionals, both in health- and social care. Although these meetings affected her possibilities for participating, it did not make her stop fighting for her rights to participate in her own treatment and care. She described being angry, feeling discriminated against, but she continued to fight for her right to participate.

Opposing the experiences of not feeling invited to participate or having ones opinions validated by professionals, Malena described an interaction with a psychologist where she had felt acknowledged, leading to an increased feeling of user participation.

He was incredibly good. And he was very calm and let me finish what I was saying and stuff and he was very good and sort of sensed… [I] left with a properly good feeling; wow, this time I was heard properly for the first time almost!

Justine also shared a positive experience. Explaining that participation was very important to her as she wore orthotics and needed them refitted regularly, she said that

Yes, I feel that I am heard. Always really, of the health services and, yes. So, so, I have a positive experience with that, as I said, I get help when I need help and feel that it works pretty good.

Her experience was based on having a constructive dialogue with the health professionals she met, and this assured the quality of care she needed.

Discussion

The aim of this paper is to contribute to new knowledge regarding how user participation unfolds for young persons as they transition from health- and social services for children to services for adults. Our results led us to theorize about the interrelatedness of user participation, developing a theory of the Interrelated process of becoming independent in user participation for young persons living with disabilities.

The results of our study points to two things: Becoming independent in user participation is a learning process that occurs over time, and it is interrelated with three aspects: parental support, increase in skills, and interactions with professionals in the health- and social care system. Our results reveal how the process of becoming independent in user participation contain different, yet equally important aspects, that either reinforce of impair each other. Thus, they reveal significant nuances regarding how the process of becoming independent in user participation is highly interrelational. The interrelational aspects needs to be acknowledged to increase young person’s possibilities of becoming independent in user participation when transitioning to services for adults ().

Figure 2. The interrelated process of becoming independent in user participation.

In the following section, we discuss how acknowledging the interrelated aspects is necessary to recognize the complexity of the process of becoming independent in user participation, and that this knowledge can increase our understanding of how young persons’ work to become independent and efficient in user participation.

Increasing skills

In Norway, one of the strategies for increasing the populations’ ability to engage with and make decisions regarding their own health, i.e. user participation, is to increase the overall populations’ health literacy (HL) [Citation30]. Barello et al. [Citation31] argued that the quality of care is affected by HL. The result of our study shows a clear link between user participation and an acquisition of required skills. Developing verbal and written language skills to understand and convey health information, an ability to express oneself clearly and concisely, as well as self-esteem to dare to express ones needs, are all necessary to achieve a satisfactory level of user participation. These skills are clearly linked to HL. Nutbeam’s [Citation32] classification of three levels of HL; functional, interactive, and critical, are all present in our findings. We found that the participants in this study had a high level of functional HL due to having extensive experience in living with a disability as well as interacting with different health professionals over longer periods of time. It is, therefore, mostly of interest to discuss interactive and critical HL in this paper.

Interactive HL is described as the ability to actively participate, derive and apply information in changing circumstances, and critical HL as the ability to critically analyse information to gain greater control over ones’ life [Citation32]. Participants experienced interactive HL as important, focusing on the importance of conveying their messages across to professionals and being acknowledged. They also experienced a need for re-establishing connections with services when transferring to adult services. This possibly disrupted the process of learning user participation. Our findings are in line with those of Bekken et al. [Citation6] showing that the transition between services appeared to have a negative effect on the rapport between the young persons and professionals.

The result of our study also shows why it is not enough to focus on increasing HL to ensure user participation for young persons with disabilities. User participation and HL were dependent on parental support and interactions with health- and social care professionals. Although being an important strategy to ensure effective and useful engagement with services, our results highlight that a one-sided focus on increasing HL for this group of young persons will not be sufficient. More importantly, the result of our study clearly shows that the participants learned their HL skills from health-literate parents. This is in line with previous research [Citation5,Citation33].

Reducing parental support

Parental support was an ongoing process of engaging, disengaging, then re-engaging the parents’ help and support. Most of the participants described parents as being heavily involved to start with, then gradually reducing the support. This was a mutually agreed two-way process, where the parents gradually withdrew, and the participants took over an increasing number of tasks and responsibilities. The process of reducing support was highly linked to the young persons’ increase in skills and abilities necessary to effectively participate. This is in line with research by Nyguen et al. [Citation33], showing that parents encouraged their adolescents to become independent and take on more responsibility.

However, the parents lingered in the background, ready to increase the level of support whenever the participants needed to re-engage their parents. Our study showed that the need to re-engage parents would often occur in relation to engaging with services they had not previously engaged with. This is in line with previous knowledge about young persons need for support during the transition [Citation34]. Another reason for re-engaging parents or requiring parental support was experiencing problems of power relations in health- and social care settings. Using parents to restore power in relations with professionals was the result of experiencing unmet needs in interactions with professionals, resulting in less independence in user participation and an increased reliance on parental support.

Bekken et al. [Citation6] identified that professionals working in children’s services stressed that when becoming an adult, young persons had to engage with services independently. The need to re-engage parents contrasted with this contextual expectation of independence. Contrary, our results show a need for continual support after the age of eighteen, highlighted by some of the young persons’ experiences of needing to bring along a parent in order to make their voice heard. This is concerning, as user participation should not be a result of power, but the default setting by which services operate, providing service users with influence and co-determination [Citation16].

Our findings about this matter provide knowledge about why professionals should be open towards cooperating with the parents of young persons, providing young persons’ consent to such cooperation.

Responding to actions

There is already a body of research regarding the importance of relations between patients and professionals for user participation [Citation6,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25]. Despite the knowledge gained from previous research highlighting the importance of professionals responding adequately to young persons’ levels of knowledge and skills, our study showed that the participants experienced that their needs were unmet, which hindered their ability to independently participate in their own health- and social care. Bekken et al. [Citation6] findings illustrate the problem with resources from the perspective of professionals. Lack of time and resources affected the professionals’ possibilities to connect with the young persons about issues that were important to them. From the results of our study, we find it plausible to assume that a lack of connection and approachability affected the young persons’ user participation. This finding accentuates the interrelatedness between the three aspects; Not being met with sufficient time and approachability led to alienation, affecting participants ability to utilize their skills independently, affecting their participation, thus requiring an increase in parental support.

Although the participants in our study were active and strived for autonomy, there is a need for professionals to focus on relational aspects. Psychosocial readiness plays an active role in user participation [Citation31]. However, this readiness does not arise without support. The result of our study shows that the participants responded better to professionals they found approachable, which increased their experience of being able to engage in user participation. Being able to express personal needs required such a readiness, but it also clearly required being met with a supportive attitude. The participants valued approachable professionals who took the time to hear them out. Stressful environments had the opposite effect. This is in line with previous research regarding professionals’ use of time [Citation25], flexibility in communication [Citation26], and equal and complimentary status [Citation24].

Understanding how the process of user participation unfolds from the perspective of young persons requires recognition of young people’s perspectives and the contrast to how their priorities might differ from the perceptions of relevance for an adult working in health care [Citation5,Citation35]. Our study shows that young people have competencies and skills but to fully apply these they need to be met in a more supportive way by professionals.

Acknowledging the complexity of becoming independent in user participation

Our results show that there is a need to recognize the complexity of becoming independent in user participation. From the perspective of young persons living with disabilities and chronic disease, the process of becoming independent in user participation is highly intertwined with health literacy skills such as navigating services, expressing ones needs, and bureaucratic competence. These are all skills they are supported in learning mostly by their parents. This requires a continual but decreasing involvement of parents, showing that parents play a vital role in preparing independence and teaching their children the necessary skills to participate.

Stewart et al.’s [Citation5] findings of transitions to adulthood as a complex and non-linear process acknowledge the need to see different aspects of transitions in a complex combination, and not as separate components. The result of our study confirms the need to recognize that young persons with disabilities process of becoming independent in user participation occurs over a prolonged period. Moreover, in our study, we identified three vital interrelated aspects in this process: increasing skills, decreasing parental support, and relational aspects.

A change from paediatric services to services for adults is a challenging process [Citation6]. Young persons’ experience many changes at this stage of life, such as moving out from home, transitioning through the educational system and attaining employment [Citation5]. Bekken [Citation34] points out that there is a structural void between what services offers of support and what the young persons’ expectations are in relation to participation and citizenship. This creates many new situations where their previous knowledge is challenged, and they may not feel equipped to meet anticipations of active participation.

The participants in our study experienced the process of becoming independent as a process of taking two steps forward one step back. They gradually gained independence, but for quite some time still invited their parents back into the process. It is necessary to acknowledge that the young persons invited their parents to support them. This shows that young persons have a conscious attitude towards how they can “use” the competencies and experience of their parents, and how it can benefit them.

Recognizing the complexity of how user participation is learned can help services and professionals develop strategies for enabling user participation from an early stage of the transition period. What complicates matters, is that the interplay between these aspects is not a constant or necessarily mutual process. Any one of the factors may be at play, either mutually or to a various degrees, depending on the context of the situation. This is especially evident in relation to the interaction with health- and social care professionals. Less satisfactory interaction requires having to work harder at utilizing the abilities just acquired, as well as a need to re-engage parental support. However, if these aspects are not acknowledged by health- and social care professionals, young persons’ ability to participate with health and welfare services are at risk.

Strengths and limitations

Despite being a small-scale study, the similarities and richness in the descriptions of experiences of user participation between the participants is a strength of this study. Further, similarities were strong even though the participants had a variety of disabilities and diseases and were in touch with a variety of services. As this is a grounded theory study, it is a strength that theoretical sampling was conducted, ensuring a theoretical saturation of the phenomena in question.

Qualitative studies do not aim to generalize results to wider populations. However, the results from our study overlap with previous studies. This shows two things: our study has relevance in that it confirms previous research, and importantly, looking at the aspects in combination, our study reveals conceptual interrelatedness. Grounded theory as a method focuses on exploring processes (descriptions) and generate grounded theory regarding the phenomena (theorizing). Although our study does not develop a substantial theory per se, we do theorize regarding the interrelatedness of the process of becoming independent in user participation, thus advancing knowledge regarding the complexity of user participation. Further studies regarding conceptual interrelatedness should be conducted, preferably in a larger scale.

It is important to acknowledge that vulnerability is inherently human [Citation36]. Involving young persons with disabilities in research entails discovering possible vulnerable parts of peoples’ lives, thus perhaps increasing their overall vulnerability in the research context. Taking part in this study was identified as low risk with regard to causing distress or harm. However, to minimize risk the interviews were design to create a balance between exploring negative experiences as well as positive experiences. The participants were also invited to contact the first author if they needed a chat following the interviews. The participants who took part in the follow-up interviews expressed being glad they participated, as sharing their experiences and contributing to research provided feelings of empowerment.

Conclusion

Our findings unveil implicit structures that come to play and reveal significant nuances containing important knowledge to further development of best practice. Acknowledging that user participation is a process containing the reciprocal and interrelated aspects of increasing skills, parental support and interactions with professionals is an important step towards understanding the complexities of how young persons with disabilities become independent in user participation. Our results strengthen the relation between the concept of user participation, health literacy, and relations with professionals, but more importantly, reveal how parental support plays a part in learning to become independent in user participation. Understanding the complexity of the process of becoming independent in user participation is necessary to enable user participation among young persons with disabilities and chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the young persons who participated in the study for sharing their experiences.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The research project obtained ethical approval by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) no. 865327.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beresford P. A participatory approach to services and support. In: Eide AH, Josephsson S, Vik K, editors. Participation in health and welfare services. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017. P. 66–78.

- Birnbaum F, Lewis D, Rosen R, et al. Patient engagement and the design of digital health. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):754–756.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, et al. ‘Participation’: a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(1):29–38.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability developmental medicine and child neurology. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(1):16–25.

- Stewart D, Law M, Young NL, et al. Complexities during transitions to adulthood for youth with disabilities: person-environment interactions. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(23).

- Bekken W, Ytterhus B, Söderström S. In the next moment I answer, it is not possible. ‘professionals’ experiences from transition planning for young people. Scand J Disabil Res. 2021;23(1):338–347.

- Eide AH, Josephsson S, Vik K, et al. Introduction and rationale. In: Eide AH, Josephsson S, editors. Participation in health and welfare services. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017. p. 1–19.

- Söderström S, Hemmingsson H. Digitalised communication and social identity. In: Eide AH, Josephsson S, Vik K, editors. Participation in health and welfare services professional concepts and lived experience. London: Routledge; 2017.

- Angel S, Frederiksen KN. Challenges in achieving patient participation: a review of how patient participation is addressed in empirical studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(9):1525–1538.

- Bröder J, Okan O, Bauer U, et al. Advancing perspectives on health literacy in childhood and youth. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(3):575–585.

- Seim S, Slettebø T. Collective participation in child protection services: partnership or tokenism? Eur J Soc Work. 2011;14(4):497–512.

- Kvam L, Pedersen H, Witsø AE. Participation at the interface with health and welfare services. In: Eide AH, Josephsson S, Vik K, editors. Participation in health and welfare services. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017. p. 90–101.

- McCormack L, Thomas V, Lewis MA, et al. Improving low health literacy and patient engagement: a social ecological approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):8–13.

- Askheim OP. User involvement discourses in norwegian welfare policy. Tidsskr Velferdsforsk. 2017;20:134–149.

- Askheim OP, Christensen K, Fluge S, et al. User participation in the Norwegian welfare context: an analysis of policy discourses. J Soc Policy. 2017;46(3):583–601.

- Guldvik I, Askheim OP. Constructing user participation for disabled people -the Norwegian context. Disabil Soc. 2021;37(9):1397–1416.

- Boniwsky S, Musto A, Suteu KA, et al. Independence: an analysis of a complex and core construct in occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75(4):188–195.

- Dasher J, Hollingsworth H, Gross J, et al. editors. Environmental determinants of quality of participation in healthcare settings among people with impairments and limitations. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2017.

- Johannessen A-K, Tveiten S, Werner A. User participation in a municipal acute ward in Norway: dilemmas in the interface between policy ideals and work conditions. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(2):815–823.

- van Staa A, Jedeloo S, van der Stege H. “What we want”: chronically ill adolescents’ preferences and priorities for improving health care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:291–305.

- Rutz S, van de Bovenkamp H, Buitendijk S, et al. Inspectors’ responses to adolescents’ assessment of quality of care: a case study on involving adolescents in inspections. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):226.

- Bjønnes S, Grønnestad T, Storm M. I’m not a diagnosis: adolescents’ perspectives on user participation and shared decision-making in mental healthcare. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2020;8:139–148.

- Persson S, Hagquist C, Michelson D. Young voices in mental health care: exploring children’s and adolescents’ service experiences and preferences. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;22(1):140–151.

- Skagestad L, Østensjø S, Ulvik OS. Collaborations between young people living with bodily impairments and their multiprofessional teams: the relational dynamics of participation and power. Child Soc. 2020;35(5):633–647.

- Bjønness S, Viksveen P, Johannessen JO, et al. User participation and shared decision-making in adolescent mental healthcare: a qualitative study of healthcare professionals’ perspectives. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:2.

- Jager M, Reijneveld SA, Metselaar J, et al. Discrepancies between adolescents’ attributed relevance and experiences regarding communication are associated with poorer client participation and learning processes in psychosocial care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(3):332–338.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923–1939.

- Schulz PJ, Nakamoto K. Health literacy and patient empowerment in health communication: the importance of separating conjoined twins. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):4–11.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2014.

- Le C, Finbråten HS, Pettersen KS, et al. Health Literacy in the Norwegian Population. English Summary. In Befolkningens helsekompetanse, del 1. The International Health Literacy Population Survey 2019-2021(HLS19) – et samarbeidsprosjekt med nettverket M-POHL tilknyttet WHO-EHII. The Norwegian Directorate of Health; 2021.

- Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. The Mediating role of the patient health engagement model on the relationship between patient percieved autonomy supportive healthcare climate and health literacy skills. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1741.

- Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259–267.

- Nguyen T, Henderson D, Stewart D, et al. You never transition alone! exploring the experiences of youth with chronic health conditions, parents and health care provides on self-management. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(4):464–472.

- Bekken W. Negotiating embodied knowledge in the transition to adulthood: a social model of human rights. Disabil Soc. 2020;37(2):163–182.

- Fairbrother H, Curtis P, Goyder E. Making health information meaningful: children’s health literacy practices. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:476–484.

- Lid IM. Vulnerability and disability: a citizenship perspective. Disabil Soc. 2015;30(10):1554–1567.