Abstract

Purpose: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability continue to experience barriers to service engagement such as mistrust of government services, lack of culturally appropriate support, marginalisation and disempowerment. This meta-synthesis reviews current literature regarding these experiences to explain why services are underutilised.

Methods: The meta-synthesis was conducted using a meta-ethnographic approach to synthesise existing studies into new interpretive knowledge. The approach was supported by a search using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Results: Ten original research papers utilising a qualitative methodology were extracted. Synthesis of the articles revealed four concepts that were developed into a conceptual model. These include:1) History Matters; 2) Cultural Understanding of Disability Care; 3) Limitations to Current Service Provision; and 4) Delivery of Effective Services.

Conclusions: Disability services do not adequately consider the cultural needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People or communicate in a culturally appropriate manner. There are expectations that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People acknowledge their disability in alignment with western definitions of disability in order to access services. More work is needed to align disability services with culturally appropriate support to provide better health outcomes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a disability continue to experience barriers to service engagement which must be addressed.

An essential gap that must be filled in providing disability services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is the acknowledgment of culture as a resolute influence on all client interactions with providers.

A cultural model of disability may better align with the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than current medical and social models used in healthcare.

Disability services need to align better with culturally appropriate support to provide better health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

We respectfully acknowledge the distinct culture and history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and congruently affirm them as Australia’s First Peoples. Historically, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People have experienced social and economic alienation following colonisation, directly resulting in higher rates of disability, chronic illness, and disadvantage Gilroy, Dew [Citation1]. This has resulted in a perpetual distancing from health and community support services and a pervasive mistrust of government policies, with many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People apprehensive about seeking support from disability services [Citation1]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People represent approximately 3% of the Australian population, and it is estimated that they experience significant disadvantages and approximately twice the rate of disability of non-Indigenous Australians [Citation2,Citation3].

There are numerous theoretical models used in the disability sector to define disability. Two of the most widely referenced models include the medical model, which positions disability as a limitation to be corrected or adapted to fit the normative societal understanding of ability [Citation4], and the social model, which attributes deficit of ability with societal structures and inequitable opportunity [Citation5]. The medical model of disability has been widely criticised for not acknowledging the effect of psychosocial factors on the experience of disability, and for perpetuating negative bias towards people with a disability [Citation4]. Green, Abbott [Citation6] also identify that the medical model does not consider culture or recognise the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People that disability is part of a continuum of health and does not equate to inability. The social model, conversely, enables providers to acknowledge the social structures underpinning racism and colonisation experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People with a disability [Citation7]. However, attributing lack of engagement with services to the ongoing effects of colonisation places the responsibility of engagement on clients and disregards the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People with a disability do not engage with support services because support services are not meeting their needs [Citation8].

In a major reform to the Australian disability services sector, the Australian Government created the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in 2013 to address the need for quality services for people with disabilities [Citation9]. The NDIS provides funding for people with disabilities to access individualised support services that meet a person’s unique needs [Citation10]. In addition, the Australian Government released an initiative called “Closing the Gap,” which is a strategy to work in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People to improve health, education, housing, and employment. It also aims to provide NDIS support to a targeted 90% of eligible Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability [Citation1].

Both the medical and the social model of disability are reflected in the NDIS service provider model of care, with a discourse away from the former toward the latter in light of criticism for the medical model’s limitations [Citation11]. However, both academic and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations have expressed concern that the administrative approach of the NDIS model is unable to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability, because it attempts to categorise severity based on a western understanding of disability [Citation12–14]. Further barriers to service engagement include lack of culturally appropriate support, mistrust of government services, poverty, homelessness, marginalisation and lack of empowerment, and differing cultural perspectives of disability [Citation10, –Citation15]. Many parents are also apprehensive to seek support on behalf of their children who have a disability for fear of stigma, shame, and fear of them being removed into custodial care [Citation16–, Citation17]. A systematic review by Trounson, Gibbs [Citation18] identified that some of the many barriers faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People when engaging with disability services include accessibility, engagement, and lack of support. However, intersectional disadvantage is exclusively experienced by those who both have a disability and identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

Disability service providers are often the first point of contact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People who engage with support services, which offers the opportunity to build trust and foster prolonged engagement. To achieve the targeted 90% engagement of eligible Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability, the NDIS needs to understand the barriers that inhibit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People from accessing disability support services. However, there is a lack of research pertaining specifically to the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People who engage with disability support services [Citation18].

This meta-synthesis will bridge this gap in knowledge by expanding on the research conducted by Trounson, Gibbs [Citation18]. Trounson, Gibbs [Citation18] identified factors that may facilitate or impede engagement with disability support services through a review of academic and industry literature, while this review will consider engagement from the specific perspective of clients, carers and service providers who are most immediately impacted by the quality of service provision.

Thus, the aim of this meta-synthesis is to review the current literature regarding the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People who engage with disability support services to explain why services are being underutilised. It is intended that this review may identify and inform future workforce and training strategies for service providers to improve the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People seeking assistance and increase engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with the NDIS support scheme.

Method

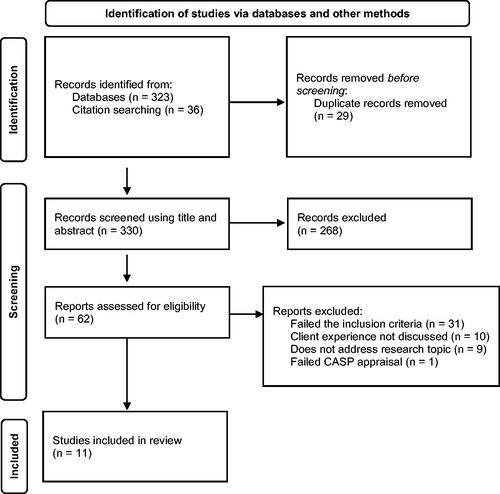

The methodology of the meta-synthesis aimed to identify and summarise research pertaining to the use of disability support services by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. The meta-synthesis was conducted using Noblit and Hare’s [Citation19] meta-ethnographic approach which is widely used to synthesise existing studies into new interpretive knowledge. The meta-ethnographic approach was supported by a search of the literature conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method to ensure the process was transparent and accurately reported ().

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of search strategy.

The seven phases of Noblit and Hare’s [Citation19] meta-ethnographic approach were utilised to conduct the meta-synthesis. This included: 1) getting started – choose a topic for the study; 2) decide what is relevant to the initial interest; 3) read the studies repeatedly; 4) determine how the studies are related, listing key metaphors, phrases, ideas and/or concepts; 5) translate the studies into one another; 6) synthesise the translations into a second level of synthesis by comparing the translations to one another; and 7) express the synthesis in written form.

Eligibility criteria

To conduct the literature search the following eligibility criteria were applied: 1) the study must discuss the client experience or utilisation of disability support services by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, 2) the support services must be located in Australia, 3) the study was published as an original research article in a peer-reviewed journal, written in English, 4) the study was published between 2012 and 2022, and 5) the study used a qualitative data analysis method.

Client experiences from the perspective of the client, parent, carer, or service provider were accepted to provide a broad perception of client interaction with disability support services. Studies were excluded if they did not comply with the aforementioned inclusion criteria or did not aptly relate to the research topic.

Search strategy

The search was conducted in August 2022 using Informit, EBSCO, and Wiley databases. Search terms are displayed in , which includes their variations and truncated terms. The search was directed by a Boolean search strategy whereby search terms were separated by “and”/“or.”

Table 1. Search terms used in the literature search.

Study selection

Study selection was performed using the PRISMA flow chart (see ). Search results were sequentially assessed by title and abstract and articles not relevant to the review were excluded. This assessment process was conducted by six authors. The remaining papers were then screened full-text and cross-checked by three reviewers to ensure consensus. Duplicates and papers which failed the eligibility criteria were removed. This included articles that were not specific to Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Peoples, not specific to people with a disability, did not discuss the client experience, focused specifically on dementia or physiotherapy services, were not original research, not published in a peer-reviewed journal, quantitative studies, or did not satisfactorily assess the research topic. The reference list of remaining articles was then examined to ensure all relevant papers had been identified.

Quality Appraisal

Selected articles were critically examined to ensure scientific rigor, credibility, and relevance using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research [Citation20]. Articles were rated as a percentage of compliance and scores less than 70% were excluded from the analysis. All final articles were assessed by all authors.

Analysis

The study selection identified 11 papers for review. The Matrix method was then used to assist in the extraction, critique, and summarisation of selected studies (Goldman & Schmalz, 2004). The author(s), year, country, aim, data collection method, support service, participants, key findings, and CASP score are presented in . Subsequently, the seven stages of meta-ethnography were utilised to conduct the meta-synthesis [Citation19].

Table 2. Summary of the included literature.

The first phase of Noblit and Hare’s [Citation19] meta-ethnographic approach – getting started – was initiated when a gap in the literature regarding the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People engaging with disability support services was identified. It was identified that only qualitative studies are relevant to this topic of interest as the gap in the literature relates to understanding clients’ experiences. Following study selection, the authors met to discuss the papers at length and read the material repeatedly to determine how the studies were related. Key metaphors, phrases, ideas, and/or concepts of each article were listed, before translating the studies into concepts and third-order constructs to create a new whole of multiple parts. Following the terminology of meta-ethnography [Citation19], first-order constructs are defined as participants’ quotes, second-order constructs are the researcher’s interpretations, third-order constructs are themes that emerge, and fourth-order constructs describe the development of new concepts. All authors collaborated to generate the third- and fourth-order constructs and prepare the final article.

Results

The final data set consisted of ten original research papers utilising a qualitative methodology. The studies encompassed a wide range of disability support services, including Government and non-government-funded disability, health, and social services, Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, an Indigenous Respite Centre, a paediatric clinic, and a child development clinic. The studies explored the lived experience of people who engage with disability support services including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability as well as parents, carers and service providers. Clients included both children and adults who engage with disability support services. A summary of included literature is presented in .

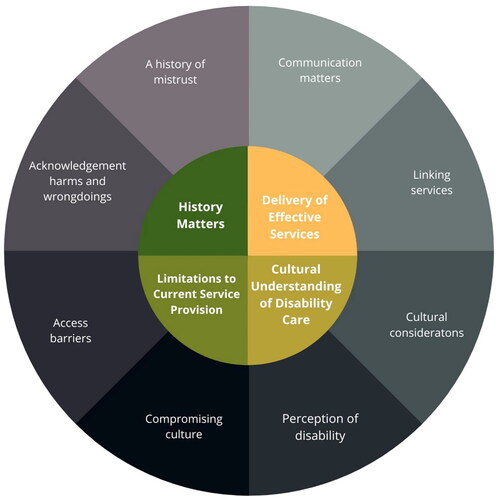

Synthesis of the selected articles revealed four concepts: 1) History Matters; 2) Cultural Understanding of Disability Care; 3) Limitations to Current Service Provision; and 4) Delivery of Effective Services. Several elements formed each concept, as displayed in . The meta-ethnographic approach revealed an interconnected relationship between the experiences of service providers and service clients, and an overarching theme of culture that permeated all concepts ensuing from the analysis ().

Figure 2. Conceptual framework for the provision of disability support services for indigenous Australians.

Table 3. Summary of emerging concepts.

Theme 1: History matters

History of colonisation and the social implications of acculturation are deeply embedded in the Australian Indigenous history. Multiple strategies have been implemented to improve relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and governments, however, a pervasive sense of suspicion and uncertainty remains that was embedded throughout the reviewed articles.

A history of mistrust

The history and generational experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People are remembered acutely and influence interactions with service providers. The reviewed literature reflects a common element of mistrust present in client/practitioner interactions, the NDIS and of support organisations in general.

“It’s easy to think of it as a historical event that happened and we’ve moved on but it really wasn’t that long ago, and it is something that’s still alive in the minds of people who are alive today … I can understand where they’re maybe reluctant to trust in a system that’s been imposed on them.” [Citation8]

Disability and NDIS service providers have a critical role to play in developing trust with their clients where a history of mistrust is present. It is essential that the time be taken to build trust between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and disability service providers, and that all interactions encompass respect and open communication.

“It’s hard as to a new situation when it comes to Aboriginals … but [the health care provider] might have had a bad day, and something [the health care provider] said and they [Aboriginal carer] just walk out and they’ll never come back, and that child goes without because of that happening.” [Citation15]

Within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities, there is a strong fear of government intervention and regulation. Mandatory reporting laws requiring specified organisations to report suspected child abuse and neglect to government child protection services of child abuse and neglect is designed to provide a point of intervention and protect vulnerable clients. However, some providers identified that mandatory reporting erodes trust with clients and prevents open communication for fear of initiating the involvement of child protection services.

“I’d say that a lot of the difficulties we’ve had with Aboriginal children too is around perhaps child protection … that child protection may get involved and then there’s a whole new aspect of the service provision.” [Citation8]

Finally, some support services have been transitory with no continuous or long-term staff to build respectful and trusting relationships within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People were suspicious about the intention of support staff indicated by this support worker’s reflection:

“I think initially I was just seen as, ‘This will be another blow-in [short term worker]. When you gone?’ So, there isn’t a trust factor that [workers] are committed. The damage that we can potentially do to Indigenous communities thinking we’re here to do the right thing but in turn it’s very disempowering…” [Citation21].

Acknowledgement of harms and wrongdoings

Acknowledging the maltreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People is crucial to bridge the gap of trust between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and non-Indigenous Australians and the history which defines interactions and relationships. The fear and distrust that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People have for government and service providers is not easily waylaid by providers with good intentions:

“trans-generational trauma has left a blot on the psyche of every Aboriginal Australian person.” [Citation7]

“… Auntie Lily thought this was because of what had happened when white men came. They brought alcohol and changed diets so they moved away from the traditional bush food and had more sugar and flour. She thinks this is why so many Indigenous People are overweight and why there is so much diabetes. She also wondered if this was why cancer was becoming more common in the Indigenous community.” [Citation22]

Theme 2: Cultural understanding of disability care

Connection to family and country is central to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples identity and sense of self. Cultural connection, connection to land, and kinship are essential for good health and living. These factors often influence their experience and perception of disability.

Cultural needs

To engage families in service provision, it’s important to understand the cultural complexities that influence their experience and adjust service provision accordingly. Some clients prefer to have access to an Indigenous service provider. This is often important because of lack of trust and because of concerns that non-Indigenous providers won’t know how to respond to individual needs.

“She can’t get minded by a lot of people because they don’t know what to do with her.” [Citation23]

Conversely, some clients prefer to see a non-Aboriginal worker due to the structure and closeness of Aboriginal communities and complex kinship which can cause the client concern for confidentiality. For these reasons, it is essential to consult with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People to develop culturally appropriate services tailored to each individual. For example, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents share the responsibility of caring for children within their extended family, making it difficult to access services when the child is being cared for by somebody other than a parent and the arrangement is casual or informal. For carers of family members or children with a disability, it is often difficult to navigate the complexities of the NDIS.

“Carers have to do the hard yards to get support…” [Citation17]

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People are disinclined to seek help from mainstream disability services because there is a preference for seeking help from within their own community or fear that assistance will be accompanied by judgement. A carer of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child with a disability explained that:

“Black fellas are very sceptical of getting outside help. They’d rather go to their own people and feel like they’re not judged…” [Citation15]

Perception of disability

With colonisation came a definition of disability which had previously been absent from Aboriginal culture. To have a disability is to experience the absence of ability, yet this cannot be assumed for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Within Aboriginal communities, disability does not equate to a loss of ability because it does not equal loss of kin or community. Being Aboriginal is central to identity, rather than any loss or lack of ability being dominant. In the author’s own words, King, Brough [Citation22] explain that “Losing a leg through diabetes is a physical hindrance, but if interaction with family, kin and community continues there is no ‘disability’”. Being Aboriginal often becomes an advantage when considering disability because kin and culture share the responsibility of caring.

“…there was an older guy…he would have been 25, 30 with an acquired brain injury and it was just accepted in the community that he did certain things. You know, that he cruised around, stayed at different places and had little systems set up around the town for getting what he needed through the day…” [Citation21]

King, Brough [Citation22] describe their interactions with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with a disability, explaining that many statements were reflective of “Indigenous first, disabled second”. One participant described how the experience of losing their mobility was accompanied by a feeling of relief when they realised they “could still go to Elders meetings because they [Elders] would pick her up” [Citation22]

The perception of disability as being different to that of western cultures is exemplified by reports that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People do not identify themselves as having a disability:

“we started travelling to remote and isolated Indigenous communities… and they would say, ‘Oh look, we don’t have anyone here with a disability.’ We would travel to that community anyway… over the course of a couple of days, from a community that said it had no people with disabilities, we saw about nine to ten people with various forms of disability in their homes.” [Citation22]

“If people don’t have access [to the Lands], and if that’s an access lost because of physical disability, if it’s a loss because you’re tied to that dialysis machine three times a week, if it’s because you’ve got this big heart problem and the clinic says you’re too unstable to be back out on country, then it’s the loss of all that is significant for being Anangu.” [Citation21]

This perception of disability creates a discourse between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and service providers because to receive help requires the acknowledgement of a diagnosis and label that may not align to the clients’ cultural views. Without a clinical diagnosis, providers may find it difficult to deliver services within the biomedical model of care that is the norm in Australia. This may be seen as another form of disempowerment that has impacted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People since colonisation and contributes to a reluctance to engage with service providers.

Theme 3: Limitations to current service provision

Culture and perceptions of disability often create a barrier that prevents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People from seeking help or accepting help offered by service providers. Or, where help is accepted, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People may be required to compromise culture to conform to a medical model of treatment that does not align with their values.

Access barriers

The complexities of modern care models can act as a barrier to service access. Often, multiple organisations serve a similar purpose with the overlapping scope of clients. This makes it difficult for clients to know who to go to and when, and how to traverse multiple service providers concurrently, particularly within the NDIS model where clients are responsible for choosing the services to suit their needs. Similarly, there is inadequate communication between services that prevent a streamlined approach to the client accessing appropriate services in a timely manner. If providers don’t have a detailed understanding of other services available in the area, it is unrealistic to expect clients to know this information.

“…if you’re [a carer] in a very stressful situation and trying to find a service and you’ve rung five and they’ve all said, ‘‘well, not us, do you want to try them?’’ I mean you’re going to give up.” [Citation8]

It is commendable that within the reviewed studies, many services available through the NDIS for clients with a disability do not incur any costs for service access. However, it is the secondary costs associated with accessing services that can act as a barrier. For example, transport costs, childcare, and respite can become so expensive that accessing care becomes unattainable.

“So yep, it doesn’t help a lot of the families that have the younger kids and that’s why - and I’ve always said that that’s why they don’t get seen to the right people because of the financial cost of that.” [Citation6]

Despite ongoing efforts to educate providers and deliver clear, culturally appropriate policies, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients experience stigma and stereotyped prejudice.

“Because I’m Aboriginal, like, it’s harder to get things done because half the time … doctors, hospitals, like, they look down on me, like because of my color, yeah, the color of my skin and, like, they talk to me like I don’t know nothing …” [Citation15]

Stigma also extended to generalised negative attitudes including reports of pity and superiority from providers, making clients even more apprehensive about seeking ongoing support: “They make you feel like they are doing you a favour by giving you respite” [Citation17]

The influence of negative past experience can erode trust and make it difficult for providers to engage clients in future. DiGiacomo, Delaney [Citation17] report that some mothers express fear of being held accountable for their child’s disability if they seek help, preventing engagement with services and delaying treatment. This is in the absence of high-risk behaviour such as drinking alcohol, smoking, or illicit drug use:

“They [organisation staff] make you feel like you caused it [the disability]…. You could be an angel and they would still criticise you.” [Citation17]

Compromising culture

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People have a strong culture of belonging to Community and connecting to Country. This is exemplified by the perception of disability only having negative connotations if it prevents engaging with Community. The hierarchy of traditional Aboriginal communities gives great respect to Elders who are looked to for guidance in many aspects of life. However, this guidance does not always align with medical advice nor does it always encourage engagement with disability services. When a dissonance occurs between the advice of medical practitioners and that coming from Elders, many parents or carers can find themselves in a difficult position of choosing between culture and care which can delay seeking diagnosis and treatment:

“Yeah, you let things slide. You just – it’s not that you don’t want to put the effort into it and go and sit around and take them out of school or anything like that, it’s just you’ve got your elder saying to you, “No, they’re right. They’re right. Don’t worry about it. They’ll pick up in their own time,” and sometimes they don’t.” [Citation6]

“We’ve got an environment that we’re trying to deliver a service [within] these parameters of “first world” doctrine. So, funding requirements, policy requirements, legislative requirements etcetera but we’re working in an environment where this community isn’t mainstream… there’s a whole set of other traditional and cultural parameters and structure to this community.” [Citation21]

“My culture is more time sensitive whereas [for] Indigenous [people], communities and families [are] more important. The event is more important than what time. I know I’ve offended Indigenous People because I only had an hour that I delegated to be with them.” [Citation21]

Theme 4: Delivery of effective services

A major factor affecting ongoing engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with disabilities with services is the complexity of service structures and services received. If it is difficult to identify and access the correct service, or if the experience is not constructive, then clients are less likely to continue engaging with providers.

Linking services

The transitory nature of some provider positions causes a disjointed experience for clients where they are continuously being seen by new staff and where complex conditions are not being managed effectively:

“One man [worker] has already written down my entire history… and because of that I had the understanding that there would be some help and things would improve, and I felt optimistic for a while. But nothing happened…. I am always recounting my story to piranpa (whitefellas) who come and ask me questions, asking if I need any help. But it never comes.” [Citation21]

“When you go for meetings and there’s constantly new people, there is those gaps, because information has not been passed on and you feel you’re just repeating yourself…” [Citation24]

The ability of service providers to offer continuity of care is essential to delivering an effective service, particularly for complex cases. In some circumstances, this is an appropriate role for a caseworker who can liaise with the client and assist them to navigate the support service system.

“If they had someone that was there, a consistent go-to person that knew their health journey, knew as they moved through the system, they wouldn’t be starting each time they presented somewhere to reestablish trust”. [Citation8]

Consultation with Aboriginal communities and access to service providers who are members of the Aboriginal community can also help to overcome reluctance to engage with services. This also provides non-Aboriginal providers with a cultural mentor to improve their understanding of cultural considerations and client needs.

Communication matters

Communication was identified multiple times as key to establishing a relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients that would support engagement with services. Similarly, it was a recurring factor for why clients became disengaged or were dissatisfied with a service. In some cases, this was simply due to providers having a limited or inadequate understanding of culture and client needs. Other times, it was unsuitable for the client due to cultural factors that had not been considered or were incompatible with the suggested treatment model or the services offered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients were often seen as tokenistic and unhelpful, described as “treat them and street them kind of attitude where it’s like get them in, tick the boxes, get them out” [Citation7].

“Bureaucracy, and the confidentiality, and the lack of understanding of the cultures here is a massive hurdle. [We need] more culturally appropriate services, more understanding about what the demands are. [Workers] don’t know anything. [Workers] are like, “Why did you miss your dialysis?” [Anangu] need to be [in their community] for that sorry [business] (funeral). So, they’re going to miss two dialysis [sessions], but then they go to the hospital, and they’re just berated by nurses, “You’re cheeky. You’re naughty. You missed.” [Citation21]

Clients with a disability reported feeling like their concerns were dismissed or no time was taken to explain the situation to them. One client explained:

“… it feels like everyone just keeps kicking, kicking, kicking, kicking! It’s like, ‘Just let me try [to] get back up and try to get back on my feet’, and it’s hard … I feel like no one listens to me when I go there to see them.” [Citation25].

“I was confused that time. They just popped out of nowhere. I didn’t know they were coming. I was surprised and a little bit frightened … When they come I want a straight story from them that I can understand … The missed me with their words they were using. I rang up J…… and asked her who they were. We didn’t know.” [Citation26]

“It was months after she was diagnosed that I found out how serious this was.” [Citation17].

Conversely, an ongoing and consistent relationship with service providers enables clients to build trust and confidence in the services they receive. One carer talked about her mother needing someone:

“… who is really kind to her and will take her out…that’s when … she starts trusting that person. That’s when it builds up and she will say, ‘Hey, you are a good person! I like you! I want to go out with you’.” [Citation21]

“We want kind people to come…. Friendly. Not just coming here and giving a talk and then go. Useless. That’s useless. No good.” [Citation21]

Kind, respectful and informed communication was identified as key to building trust and improving engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients.

Discussion

A consistent finding within each of the articles reviewed was that disability services do not adequately consider the cultural needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People or communicate in a culturally appropriate and considerate manner. This is contributed to, in part, by an expectation that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People acknowledge their disability in alignment with the western definition of disability in order to access services [Citation18].

Both the medical and the social model of disability are reflected in Australian service provider models of care [Citation11]. However, neither theoretical model recognises specifically the unique experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with a disability. As an alternative to the traditional medical and social models of disability, the cultural model affords an opportunity for definitions of disability to acknowledge the importance of culture in influencing client interactions with providers. While a precise description of the cultural model of disability has not yet been widely adopted [Citation27], it is broadly understood as the lived experience of disability that both effects and is effected by the culture in which it occurs [Citation28].

An essential gap that must be filled in providing disability services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People is the acknowledgment of culture as a resolute influence on all client interactions with providers. In relation specifically to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Avery [Citation14] describes the cultural model of disability as focusing on individual wellbeing via connection with kin and community, rather than emphasising impairment or debility.

The cultural model provides a template for acknowledging the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People who engage with disability service providers as identified in this review, including the history of colonisation [Citation7,Citation8,Citation15,Citation22], the importance of connection to Land, kin and Community [Citation17,Citation21,Citation23], having to conform to a western definition of disability [Citation22,Citation25], and the role of culturally appropriate communication in building trust and rapport [Citation24–26].

Research on the use of culturally guided models of care is extremely limited, however early studies have found that carers report more positive experiences with providers, more holistic inclusion of family, and better quality of care for children with a disability [Citation15]. The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) has been established in Australia to promote and provide a holistic model of care within in the primary healthcare system. However, caution is required in that categorisation by culture can lead to the unintentional consequence of stereotyping and bias, where providers focus exclusively on the clients identification as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and overlook the experience of having a disability [Citation15]. Further, conflict exists between the consideration of culture and the staff-client model of support as it now stands. King, Brough [Citation22] acknowledge that to make accommodations for cultural ways of interacting may compromise the structure of service provision in a way that is difficult to reconcile with the Australian Government’s principles of governance. A compromise must be found that allows service providers to adopt a cultural model of care while maintaining Australian standards and policy.

Applying this concept to the NDIS, the system is designed to be customised to each individual’s needs which allows them to seek appropriate care and assistance for their own requirements. However, it can be difficult to have support initially approved due to the complexity of the system and the labour-intensive process of individual assessment. Research has categorically demonstrated the disconnect in the engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with disability services, and a cultural model of understanding disability could help to increase utilisation of services. However, the theoretical framework for the cultural model of care is significantly underdeveloped and merits further research.

Review limitations

This review reported on giving and receiving the provision of services for people with disability from the perspective of multiple shareholders, including clients, carers, parents and service providers. However, only a limited number of articles provided insight directly from clients with a disability, compared to those who interviewed parents, carers, and service providers. This may result in a biased perspective that is not reflective of the direct client experience. Furthermore, this review did not consider the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People who experience disability but are not acknowledged as such, such as those who experience communication barriers, complex mental health, or brain injury excluded from NDIS eligibility.

Similarly, the articles reviewed were more heavily weighted towards services provided for children compared to adults with a disability. Further critique of literature regarding the provision of services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People who have a disability should be conducted to distinguish between services for children and services for adults. Expanding the search terms of the review could include acquired disabilities, communication disabilities, and brain injuries all of which access disability support services. Similarly expanding the search to include grey literature may uncover a wider variety of articles. This would provide valuable insight into how the needs and provisions required for children differ from those required by adults and assist service providers to consider the added complexity of coordinating with parents and/or carers.

Conclusion

To sum up these reflections, the theoretical framework presented here demands attention to the nature of building respectful relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients living with a disability to access support service providers. This attention involves cultural understanding and lived experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living with a disability and their carers’ cultural backgrounds and conscientiousness of service providers that is arduous and intricate to engage and navigate accessing such services. Much remains to be done in constructing a comprehensive theoretical framework and identifying the inherent complexities in engaging and navigating service provision of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People living with a disability. Once we have established the extent to which questions generated by interviewees have already been addressed this theoretical framework could potentially be used to provide more engaging service provision. We are hopeful that the current findings and ongoing related work will have a real impact on people living with a disability who is in need of improved and effective service provisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gilroy J, Dew A, Lincoln M, et al. Need for an Australian indigenous disability workforce strategy: review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(16):1664–1673.

- ABS. Survey of disability, ageing and carers: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. Canberra: ABS, 2021.

- ABS. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Australians released 31/8/2018. Canberra: ABS, 2016.

- Haegele JA, Hodge S. Disability discourse: overview and critiques of the medical and social models. Quest. 2016;68(2):193–206.

- Pickard B. A framework for mediating medical and social models of disability in instrumental teaching for children with down syndrome. Res Stud Music Educ. 2021;43(2):110–128.

- Green A, Abbott P, Delaney P, et al. Navigating the journey of Aboriginal childhood disability: a qualitative study of carers’ interface with services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):680.

- Gilroy J, Donelly M, Colmar S. Twelve factors that can influence the participation of Aboriginal people in disability services. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin. 2016;16(1):1–10.

- Green A, Abbott P, Luckett T, et al. It’s quite a complex trail for families now’ – Provider understanding of access to services for Aboriginal children with a disability. J Child Health Care. 2021;25(2):194–211.

- Wiesel I, Habibis D. NDIS, housing assistance and choice and control for people with disability. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2015.

- Townsend C, White P, Cullen J, et al. Making every Australian count: challenges for the national disability insurance scheme (NDIS) and the equal inclusion of homeless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples with neurocognitive disability. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):227–229.

- Humpage L. Models of disability, work and welfare in Australia. Soc Policy Admin. 2007;41(3):215–231.

- Gordon T, Dew A, Dowse L. Listen, learn, build, deliver? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy in the national disability insurance scheme. Aust J Soc Issues. 2019;54(3):224–244.

- Gilroy J, Donelly M, Colmar S, et al. Conceptual framework for policy and research development with indigenous people with disabilities. Australian Aboriginal Studies. 2013;2:42–58.

- Avery S. Culture is inclusion: a narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. Sydney, N.S.W.: First Peoples Disability Network Australia; 2018.

- Green A, Abbott P, Davidson PM, et al. Interacting with providers: an intersectional exploration of the experiences of carers of Aboriginal children with a disability. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(12):1923–1932.

- DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Abbott P, et al. Childhood disability in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: a literature review. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(7):7.

- DiGiacomo M, Delaney P, Abbott P, et al. Doing the hard yards’: carer and provider focus group perspectives of accessing Aboriginal childhood disability services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:326.

- Trounson JS, Gibbs J, Kostrz K, et al. A systematic literature review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement with disability services. Disability & Society. 2022;37(6):891–915.

- Noblit G, Hare R. Qualitative research methods: meta-ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1988.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist Oxford, UK2018 [cited 2020 July]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Dew A, Barton R, Gilroy J, et al. Importance of land, family and culture for a good life: remote Aboriginal people with disability and carers. Aust. J. Soc. Issues. 2020;55(4):418–438.

- King JA, Brough M, Knox M. Negotiating disability and colonisation: the lived experience of indigenous Australians with a disability. Disability & Society. 2014;29(5):738–750.

- DiGiacomo M, Green A, Delaney P, et al. Experiences and needs of carers of Aboriginal children with a disability: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):96.

- Green A, Abbott P, Luckett T, et al. Collaborating across sectors to provide early intervention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with disability and their families: a qualitative study of provider perspectives. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(3):388–399.

- Soldatic K, Somers K, Spurway K, et al. Emplacing indigeneity and rurality in neoliberal disability welfare reform: the lived experience of aboriginal people with disabilities in the West Kimberley, Australia. Environ Plan A. 2017;49(10):2342–2361.

- Ferdinand A, Massey L, Cullen J, et al. Culturally competent communication in indigenous disability assessment: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):1–12.

- Devlieger P, Miranda-Galarza B, Brown SE, et al. Rethinking disability: world perspectives in culture and society: Maklu. Chicago (IL): Garant Publishers; 2016.

- Waldschmidt A. Disability–culture–society: strengths and weaknesses of a cultural model of dis/ability. Alter. 2018;12(2):65–78.