Abstract

Purpose

To identify participation-focused measures used for young people with cerebral palsy (CP), evaluate their psychometric evidence, and map item content to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), and family of Participation-Related Constructs (fPRC) frameworks.

Methods

Four databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL) were searched for papers that involved young people with CP aged 15 to 25 years and reported original data from a participation measure. Each measure was examined for validity, reliability, responsiveness (using the COSMIN checklist), clinical utility, the inclusion of accessible design features, self- and/or proxy-report from people with communication support needs, and item content according to ICF and fPRC.

Results

Of 895 papers, 80 were included for review. From these, 26 measures were identified. Seven measures (27 papers/resources) were participation-focused, capable of producing a score for participation Attendance and/or Involvement. Of these, all measured Attendance (n = 7) but fewer than half measured Involvement (n = 3). Few included studies (37%) reported including some self-report of people with communication support needs.

Conclusions

Participation measures for young people with CP are evolving but require more: (i) emphasis on measurement of involvement; (ii) investigation of psychometric properties; and (iii) adaptation to enable self-report by young people with communication support needs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Identifies seven participation-focused measures which are available for young people with cerebral palsy, all seven measure Attendance and three measure Involvement.

Provides a decision-making tool to assist clinicians and researchers with the selection of participation-focused measures for young people with cerebral palsy.

Recommends that more accessible self-report measures are needed which capture age-appropriate participation of young people with cerebral palsy.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) refers to a group of disorders of movement and posture caused by impairment in the developing brain [Citation1]. Many young people with CP face challenges to participation, during the transition from adolescence to adulthood, when needing to adapt to new life roles [Citation2]. Participation restrictions are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as problems in “involvement in life situations” [Citation3, p.10]. Since inclusion and engagement are key goals for young people with CP [Citation4], it is important for clinicians to utilise age-appropriate participation measures in order to identify required supports and services. To date, participation measure literature for people with CP has focused predominantly on school-aged children [Citation5–12], with limited research reflecting the transition to adulthood [Citation13]. Therefore, this review seeks to identify and evaluate measures for young people with CP that focus on participation during this important transition period by measuring their Attendance and Involvement.

The construct of participation is complex and multidimensional [Citation14]. These complexities result in participation being a difficult construct to conceptualise, measure, and define [Citation15,Citation16]. Several frameworks exist that attempt to conceptualise participation and how best to measure it. Two key frameworks are the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) [Citation3] and the family of Participation-Related Constructs (fPRC) [Citation17] which can be used to classify participation measures. Classification using the ICF reflects “what” participation domains or life situations are being measured, for example, Major Life Areas (d8) or Community, Social, and Civic Life (d9) [Citation3]. Whereas classification using the fPRC denotes “how” participation is being measured, with regard to Attendance or Involvement components. Attendance refers to the objective element of “being there”, measured as the frequency and diversity of experiences attended. Involvement refers to the subjective experience while participating, such as affect, motivation, engagement, persistence, and social connection [Citation14,Citation17,Citation18]. The fPRC also encourages clinicians to consider facilitators and barriers across participation-related constructs: Activity Competence, Sense-of-self, Preferences, and the Environment in which participation occurs [Citation14,Citation17]. The Environment includes five dimensions: Availability, Accessibility, Affordability, Accommodability, and Acceptability [Citation19].

The transition to adulthood can be considered to range from middle adolescence [Citation20] (15+ years) into young and emerging adulthood (up to 25 years) [Citation21]. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, individuals aged 15 to 25 years will be included as young people undergoing this transition. This age group is the focus of this research due to the rapid development of independent identity and the exploration of new participation roles in areas such as education, employment, independent living, and relationships [Citation21,Citation22]. These new life situations can be challenging to navigate, especially for young people with CP. Research shows that a high proportion of young people with CP live in their family home, are not employed or financially independent [Citation23], have less participation autonomy [Citation24], and may be disadvantaged functionally and socially compared with typical peers across multiple life areas such as education, employment, living situation, finances, and relationships [Citation2]. To address this, young people with CP may need multiple additional services or supports for participation. Therefore, age-appropriate measures are needed to capture participation experiences and needs across these areas. Existing measures appropriate for other age groups, such as children, may not capture the required contexts typical for adolescents and young adults.

There are currently no systematic reviews of participation measures for the transition to adulthood for young people with CP. Several reviews of participation measures exist for children less than 18 years. Some of these have mapped measure content to the ICF [Citation10–12], and some have mapped measure outcomes to the fPRC [Citation5,Citation9]. None have mapped measures to both frameworks and only one systematic review exists for adults older than 18 years with CP which mapped outcome measure content to the ICF [Citation13]. Additionally, studies focusing on participation measures used for adults with other diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [Citation25], intellectual disability [Citation26], spinal cord injury [Citation27], and aphasia [Citation28] have also been completed. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have reviewed participation measures available that can span across the transition age between adolescents and young adults and are appropriate for people with CP. Classifying available measures for young people with CP using both frameworks across this age group is needed to map “what” and “how” participation can be measured. This will produce a selection of more age-appropriate measures that clinicians can use to answer different clinical questions for this specific population.

Participation measures also need to be able to support self-report as participation is a subjective construct. Self-report is important as a poor correlation has been found between the reports from youth versus their parents [Citation29,Citation30], as proxies are not living the life of the individual [Citation31]. Furthermore, youth who utilise caregiver proxy to respond to measures have been found to have significantly less independence than those who can self-report [Citation32]. People with CP present with persisting motor difficulties and can have a range of abilities, associated impairments, and severities which can impact participation [Citation1]. This study focuses on CP as it is important to make sure that participation measures are appropriate for this specific group of individuals with posture and movement difficulties. Measures that may be appropriate for capturing the participation of other diagnosis (e.g., ASD, Down Syndrome), may not be appropriate or accessible for people with CP to self-report. Therefore, although these measures may be used with people who have a range of different disabilities, it is important to make sure they are also appropriate for people with CP. There is also a high prevalence of communication support needs for people with CP which is an important consideration when supporting self-report [Citation33–38]. According to the Australian Cerebral Palsy Register (ACPR) 2023 report, the proportion of youth with CP across Australia who were non-verbal ranged from 22% to 27% and those with some degree of speech or communication difficulty ranged from 59% to 68% for those born in 1996 to 2016 [Citation39]. For a participation measure to support the self-report of people with CP, it would need to have diverse and accessible considerations for people with difficulties with movement and possibly co-occurring difficulties with communication.

To date, the accessibility of participation measures for people with CP has not been described. To promote self-advocacy, it is critical for measures to provide accessibility options to enable optimal engagement by young people with communication support needs (e.g., difficulties in verbal understanding, expressive language, speech, understanding intended meaning or literacy) [Citation40]. Accessible design features in this study refer to (i) formatting of written information in a way which makes the content in the measure more inclusive for people with additional support needs, such as considerations for font, page layout, colours, and use of graphics/images [Citation41] and (ii) any technology options that enable alternative physical access to the measure. A description of the accessible design features available in participation measures is urgently needed to identify age-appropriate measures for young people with CP that can reduce the reliance on caregiver proxy-report seen in the literature [Citation12].

The aim of this systematic review was to identify and examine the participation measures reported for use with young people with CP. Objectives were to: (i) identify quantitative measures of participation that have been reported for young people aged 15 to 25 years with CP; (ii) use the ICF to map participation content (“what” is being measured e.g., education or employment) and use the fPRC to map participation constructs (“how” it is being rated e.g., Attendance or Involvement or a participation-related construct); and (iii) examine psychometric evidence available to support the use of these measures with this population. With relation to self-report, objectives were to: (iv) describe reported accessible design features; (v) identify if/how young people with CP with communication support needs were involved in the included studies; and (vi) identify any communication support strategies utilised when completing the measures in these studies.

Methods

Study design

This study was a systematic review performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42020198014).

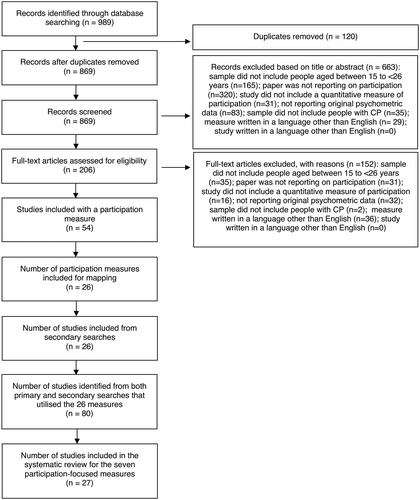

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart showing article yield of included measures during searches.

Search strategy

Database searches were completed from the date of inception to February 2023 using four electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and CINAHL. The search terms used were cerebral palsy AND participation AND (assessment OR measure OR test) AND (validity OR reliability OR responsiveness OR psychometric) and used corresponding Medical Subject Headings terms (Supplementary Appendix 1). Secondary searches were completed for the: (i) names and authors of included participation measures; (ii) reference lists of included studies; and (iii) reference lists of systematic reviews of participation measures identified in primary searches.

Selection criteria and screening

Studies were eligible if they included: (i) young people with a diagnosis of CP aged from 15 to 25 years; (ii) an English language version of a measure which produces quantitative data for participation (Attendance and/or Involvement) in specific life situations at home or in the community (e.g., at school or work), reported as a total score, subscale score, or from individual items; (iii) original data for validity, reliability, or responsiveness for that measure; and (iv) the study was published in English in full-text. Studies reporting on measures of engagement in the therapeutic intervention were excluded, there are other systematic reviews available on this topic (e.g., Tetley et al. [Citation42] and Walton et al. [Citation43]). Results from primary and secondary searches were collated and duplicates removed. Two researchers independently screened each title and abstract to distinguish which studies met the inclusion criteria. If disagreement occurred between the reviewers, a third researcher reviewed the title and abstract to provide the deciding vote. Articles included at the title and abstract level then underwent full-text review. Articles meeting all inclusion criteria were included in the review.

For this review, participation measures were organised into two groups: (i) participation-focused and (ii) participation-related. A participation-focused measure involved item content relating to participation in life situations and asked the respondent to rate their Attendance and/or Involvement, producing a score for at least one of these core participation constructs. A participation-related measure involved item content relating to participation in life situations and asked the respondent to rate participation-related constructs (e.g., Activity competence), however it did not produce a score that focused on the core participation constructs. Measures in the participation-focused category that met the inclusion criteria were further analysed for the methodological quality of studies available when used with young people with CP and for their inclusion and consideration of people with communication support needs.

fPRC and ICF construct mapping

The rating scales of the measures were mapped to the fPRC using the process described by Adair et al. [Citation5]. This process determined whether the measure was participation-focused or participation-related. If measures appeared in both this review and the study by Adair et al. [Citation5], mapping was compared to ensure consistency. The content of the measures were then mapped to the ICF using linking rules described by Cieza et al. [Citation44,Citation45] and Ballert et al. [Citation46]. The ICF domains Learning and Applying Knowledge (d1) and General Tasks and Demands (d2) were not needed as items in the included measures could be mapped to more specific domains across d3 to d9 to identify the participation experience being captured e.g., Education (d810–d839), Work and employment (d840–d859), and Recreation and leisure (d920). Mapping of measures and assessment of the studies was performed by the chief investigator using measure pages, instruction sheets, and studies related to that measure. Each allocation was discussed in detail and confirmed by the consensus of the research team.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The characteristics for each included measure were extracted using the CanChild Outcome Measures Rating Form. Psychometric data was collated for validity, reliability, and responsiveness of each participation-focused measure. The updated four-point scale of the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) checklist (i.e., very good, adequate, doubtful, or inadequate) was used to determine the methodological quality of the included studies [Citation47]. Criterion validity was excluded from the analysis based on the recommendation from COSMIN, as there is no gold standard available in the field of health-related questionnaires [Citation48]. The worst score counts method was utilised, providing a quality score for each measurement property by using the lowest rating of any item [Citation49]. Each study was given either a positive (+ positive result), negative (− negative result), or indeterminate (?) rating depending on the study results [Citation50,Citation51].

Data synthesis

The levels of evidence for the included measures on each psychometric property was determined using the guide reported by Schellingerhout et al. for psychometric reviews [Citation52], based on the recommendations for randomised controlled trials devised by van Tulder et al. [Citation53]. This method has since been used in multiple systematic reviews of measures (e.g., [Citation51,Citation54–57]). The guide was modified in this study to include the most recent COSMIN checklist rating labels for rating the methodological quality of single studies in systematic reviews of outcome measures [Citation47] ().

Table 1. Guide to synthesising levels of evidence in psychometric reviews as reported by Schellingerhout et al. [Citation52] and derived from van Tulder et al. [Citation53].

Accessibility for individuals with communication support needs

Manuals and scoring forms of each included participation-focused measure were examined to determine whether the measure: (i) was designed for self-report, proxy-report, or both, and (ii) included accessible design features (e.g., font, page layout, images) [Citation41,Citation58]. Then, each included study was examined to extract: (i) the number of participants with reported communication support needs; (ii) whether the young people responded by self-report, proxy-report, or both; and (iii) what type/s of accessible design features, or other communication supports were utilised during the study.

Results

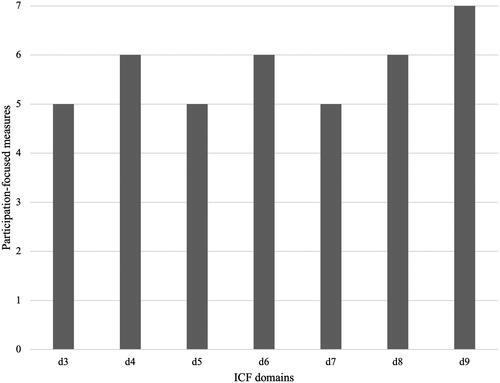

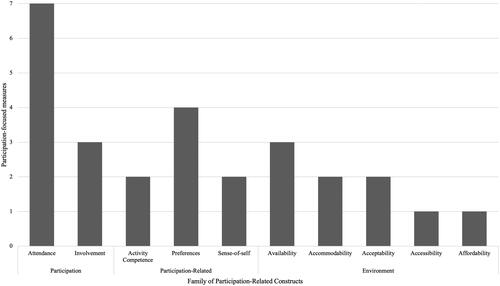

Initial searches yielded 869 articles after duplicates were removed. After title and abstract screening, 206 articles proceeded to full-text review. The full-text review resulted in 54 papers included for analysis. Secondary searches yielded an additional 26 resources, including manuals and/or other published articles about the measures, resulting in a total of 895 studies yielded from primary and secondary searches (). A total of 26 participation measures were identified, of which seven were participation-focused measures (). These seven measures were mapped to the ICF and fPRC frameworks () and their psychometric properties were examined (27 papers) ( and Supplementary Appendix 3). The mapping and characteristics of the remaining 19 participation-related measures are presented in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Table 2. Description of participation-focused measures used for young people with cerebral palsy.

Table 3. Participation-focused measures mapped to ICF and fPRC.

Table 4. Levels of evidence for included participation-focused measures reported for young people with CP.

Psychometric data and participation mapping

Results for the seven participation-focused measures are presented in alphabetical order below, including a summary of psychometric data (validity, reliability, responsiveness) with young people with CP, and mapping to ICF () and fPRC () frameworks. Following this, a summary is provided of the design features for people with communication support needs.

Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP)

The CASP was designed for young people aged 5 to 18 years. Self-report or caregiver proxy-report was used to rate the extent of the youth’s participation in home, school, and community activities. Content mapping covered seven ICF domains (d3–9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and the participation-related construct of Environment (Availability: assistive devices or equipment and Accommodability: changes to the environment). Two studies included psychometric data. Together, these studies demonstrated moderate (++) evidence of construct validity and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.87 [Citation59] and 0.96 [Citation60]). Moderate (++) evidence was also found for reliability when used with young people with disabilities including CP [Citation59].

Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE)/preference for Activities of Children (PAC)

The CAPE/PAC was designed for children and youth with and without disabilities aged 6 to 21 years of age and was the most studied measure included in this review. Self-report or caregiver proxy-report was used to rate participation in activities outside of school. Content mapping covered six ICF domains (d3–4, d6–9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and Involvement and the participation-related construct of Preferences (desire to complete activity). Psychometric data was obtained from 13 studies including the CAPE/PAC manual [Citation61]. Ten studies provided strong (+++) overall evidence for construct validity and two studies provided moderate (++) evidence of responsiveness over time. The manual also included one study that provided limited (+) evidence of unacceptable to acceptable internal consistency for the CAPE (Cronbach’s α = 0.42 to 0.76) and acceptable to good internal consistency for the PAC (Cronbach’s α = 0.76 to 0.84) [Citation61].

Frequency of Participation Questionnaire (FPQ)

The FPQ was designed for children aged 8 to 12 years. However, included papers reported using the FPQ with participants up to 25 years. Caregiver proxy-report was used to examine the frequency of activities attended at home, school, and in the community. Content mapping covered six ICF domains (d3–6, d8–9). Response mapping captured only fPRC participation Attendance. Two studies included psychometric data. One study provided unknown (?) level evidence for construct validity [Citation62] and another study provided limited (−) evidence for responsiveness following femoral osteotomy surgery [Citation63].

Participation and Environment Measures for Children and Youth (PEM-CY)

The PEM-CY is designed for young people aged 5 to 17 years. Caregiver proxy-report was used to examine participation in a range of activities and environments. Content mapping covered seven ICF domains (d3–9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and Involvement and the participation-related construct of Environment (Availability: Equipment, resources, and supports, Accessibility: Environmental access, Acceptability: Attitudes of others, and Affordability: Enough money and time to support community participation). Five studies provided strong (+++) evidence of construct validity. Of these, one study of very good quality demonstrated construct validity through hypothesis testing using the PEM-CY with subgroups of people with and without disability, finding that youth with disabilities engaged less frequently in different activities and had lower levels of involvement [Citation64]. Limited (−) evidence was found for responsiveness [Citation65] as well as limited (+) evidence of moderate to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.59 to 0.83), and moderate to good test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.58 to 0.84) [Citation64].

Participation Survey/Mobility (PARTS/M)

The PARTS/M has been utilised with young people and adults older than 17 years. Self-report was used to examine participation in major life activities. Content mapping covered six ICF domains (d4–9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and the participation-related constructs of Activity competence (level of dependence), Sense-of-self (satisfaction), Preferences (choice and importance), and the Environment (Availability: assistance and Accommodability: adaptations). One study included psychometric data for people with mobility impairments, including CP [Citation66]. This study provided limited (+) evidence for construct validity, limited (+) evidence for test-retest reliability with large association (r = 0.77 or higher), and strong (+++) evidence for acceptable to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.71 to 0.92) for participation domain scores.

Questionnaire of Young People’s Participation (QYPP)

The QYPP was designed for young people with CP aged 13 to 21 years. Self-report or caregiver proxy-report was used to rate the frequency of participation in everyday activities. Content mapping covered seven ICF domains (d3–9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and the participation-related construct of Preferences (autonomy). Two studies reported psychometric data for young people with CP [Citation67,Citation68]. These studies provided moderate (++) evidence of construct validity between subgroups, with one study reporting that young people with CP participated less than the general population [Citation67]. This study also demonstrated limited (+) evidence for unacceptable to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.49 to 0.86) and good to excellent test-retest reliability for the QYPP domains (ICC = 0.83 to 0.98).

Self-reported Experiences of Activity Settings (SEAS)

The SEAS was designed for youth with or without physical disabilities and has been utilised with youth aged 13 to 23 years. Self-report was used to rate their experience in a recent recreational or leisure activity. Content mapping covered one ICF domain: Community, social, and civic life (d9). Response mapping captured fPRC components of participation Attendance and Involvement and the participation-related constructs of Activity competence (challenging activity), Sense-of-self (personal growth), Preferences (choice and control), and Environment (Acceptability: valued and supported). Two studies reported psychometric data for young people with CP. These studies provided moderate (++) evidence for the construct validity of the SEAS [Citation69,Citation70]. The study by King et al. [Citation70] also provided moderate (++) evidence for moderate to excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.51 to 0.94), and limited (+) evidence for acceptable to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.71 to 0.88).

Accessibility for individuals with communication support needs

Of the seven participation-focused measures, only three were reported to contain accessible design features, the CAPE/PAC, PARTS/M, and SEAS (). The CAPE/PAC includes picture cards with illustrations of the participation activities, categories, and includes visual response pages [Citation61]. The PARTS/M has an online version that allows participants to select font size and background colour. Lastly, the SEAS has a Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) version [Citation71], which was developed for youth who require graphic symbol support [Citation72]. The PEM-CY also has a computer-based version available for download, but specific accessible design features were not reported for this measure. Of the 27 included studies for participation-focused measures, just over half (n = 15, 55.6%) included people with communication support needs, and less than half (n = 10, 37%) facilitated their self-report. Descriptions of communication supports were non-specific, such as providing communication assistance or proxy-report when required (8/27), further explanation to support understanding (3/27), assistance reading questions (2/27), assistance scribing or entering responses (2/27), and additional time to answer (1/27).

Table 5. Accessibility and inclusion of individuals with communication support needs.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to identify and examine the participation measures reported for use with young people with CP. This systematic review identified seven participation-focused measures which produced a score reflecting at least one core participation construct (Attendance and/or Involvement). Measures lacked strong psychometric data with young people with CP, with a particular scarcity of studies available for responsiveness. Comprehensive mapping of participation-focused measures to the ICF life domains and fPRC constructs identified that most measures focused on capturing objective Attendance (n = 7) rather than subjective Involvement (n = 3). Furthermore, only three measures were reported to contain some accessible design features (CAPE/PAC, PARTS/M, and SEAS) and most studies relied on proxy-reports of people with communication support needs. Studies also lacked specific descriptions of both the types of communication support needs of participants and the support provided for these individuals.

There is currently a lack of strong psychometric data available to support the use of participation measures with young people with CP. More studies were available for the more commonly known and used measures, such as the CAPE/PAC and the PEM-CY, compared to other measures, such as the SEAS. Five out of the seven measures had moderate or strong positive construct validity, however only three had at least moderate content validity for this population (). This highlights a need for more research in this area, particularly for self-report of participation. There was even less research available for reliability with only two measures having at least moderate internal consistency and two having moderate reliability. Responsiveness was the least investigated property, with only the CAPE/PAC having at least moderate positive evidence for responsiveness. There is a need for more responsiveness-focused studies in response to intervention, or to longitudinal changes in participation over time [Citation73]. At this stage, the FPQ has the weakest evidence across all properties with negative findings for validity and responsiveness and no studies for internal consistency or reliability. Further investigation is needed to support the use of the FPQ with this population. The development of COSMIN guidelines for devising psychometric studies and the development of the fPRC criteria to guide participation rating scales are both likely to improve future measure design and psychometric evaluation. In the meantime, clinicians and researchers need to be cognisant of available psychometric data when choosing measures for this population.

Mapping items in the participation-focused measures to ICF domains revealed a focus on the domains of Community, social, and civic life (d9, n = 7), Major life areas (d8, n = 6), Domestic life (d6, n = 6), and Mobility (d4, n = 6). Authors of most measures reported that item development was informed by strategies such as reviewing the literature, searching available measures, and interviewing people with disabilities, their caregivers, and health professionals. This suggests that these domains reflect key areas of concern for young people and their caregivers. The findings from this study are consistent with characteristics of measures reported in the recent systematic review for adults with CP, with the most frequently captured domains being Mobility, Self-care, and Major life areas [Citation13].

Most of the participation-focused measures were designed for school-aged children. There is a lack of measures and research adequately capturing the breadth of participation in young people throughout the post-school period and into adulthood. This review only found two participation-focused measures (PARTS/M and QYPP) which covered areas of economic life (d860–d879) which is an important element of adulthood. The PARTS/M also included items for managing money, maintaining a home, and intimate relationships as it was also the only included measure developed to be relevant across adolescence, young adulthood, and into older adulthood. More measures that reflect age-appropriate life situations are needed for young people with CP as they move into adult years. This finding reflects the current paediatric focus in the CP literature with a need to continue targeting participation during the transition to adulthood [Citation73].

A reliance on capturing Attendance rather than Involvement was found from mapping participation-focused measures to the fPRC framework. This is likely to reflect the comparative ease of measuring the objective frequency and diversity of Attendance, compared to the subjective experience of Involvement, which is multidimensional and complicated to measure [Citation18]. The systematic review for paediatric measures by Adair et al. [Citation5] found a similar trend. The authors emphasised that while Attendance is a requirement for Involvement, attending an activity does not necessarily mean that the individual will also be involved [Citation5]. The same is true for young people with CP. Therefore, the high number of measures that capture proxy-ratings of Attendance (n = 5 measures, 71.4%) leaves much unknown in terms of the personal experience and Involvement of young people with CP. It is important to be clear when developing new rating scale titles and criteria about which dimension of the fPRC or ICF frameworks the item and scale are addressing so that clinicians and researchers can make informed selections and utilise measures that also capture self-reported Involvement.

The focus on younger age groups may also be reflected in the reliance on proxy-report measures noted across most studies. This finding is similar to a previous paediatric systematic review by Schiariti et al. [Citation12], which reported an overwhelming use of proxy-report (94.8%) compared to combined self and proxy-report (12.1%). It is acknowledged that information obtained via proxy-report can be beneficial, particularly when working with individuals with CP who have more severe intellectual and communication impairments who may not have a reliable communication method. However, it is essential to strive for self-report where possible, as participation is a subjective construct, and poor correlation has been found between reports on wellbeing from youth when compared with their parents/caregivers [Citation30]. In addition, 55.6% of the included studies involved people with communication support needs, and only 37% attempted to include their self-report to some capacity with varying communication support strategies. Many studies tended to revert to caregiver proxy-report for these individuals. This finding is problematic as capturing an individual’s subjective participation via proxy reporting is limited, particularly when individuals with communication support needs may be able to self-report with appropriate support. Studies also lacked specific descriptions of the types of communication support needs of participants and the support provided for these individuals. Additional effort is needed to enable the self-report of young people with communication support needs and their inclusion in studies through the use of accessible formatting (e.g., the inclusion of images, white space, or larger text) [Citation58] and supportive communication strategies (e.g., repeating and rephrasing) [Citation74].

Some of the seven participation-focused measures also included items addressing other participation-related constructs. The most common participation-related construct (fPRC) items were in Preferences (n = 4 measures) and Environment-Availability (n = 3 measures). Participation occurs within a context, and the availability of a suitable Environment is strongly related to participation [Citation14,Citation18]. A previous systematic review by Maxwell et al. [Citation19] found similar results for children in the education setting, where Availability was the most commonly measured Environment dimension. Although it is promising that Availability is captured within three measures, Availability is only one of the five Environment dimensions. More measures that capture other important dimensions such as Accessibility and Acceptability are also needed [Citation17,Citation19]. This is particularly important due to recent studies that have highlighted how beneficial positive social factors can be towards establishing more favourable participation environments [Citation75]. Furthermore, four participation-focused measures captured Preferences. Preferences are a precursor to participation, reflecting the meaningfulness of the activity and choice of the individual [Citation17]. A study examining the relationship between Preferences and Involvement recommended the consideration of Preferences to promote leisure participation [Citation76]. It would be beneficial for a future systematic review to map measures focused on participation-related constructs such as Environment and Preferences to the ICF and fPRC and the psychometric evidence available for their use with people with CP. This review would highlight valuable measures such as the Measure of Environmental Qualities of Activities Settings (MEQAS), which asks respondents to rate the extent that Environment factors support Participation [Citation77]. Therefore, future research should address this need for more comprehensive measures that capture a range of both participation-focused and participation-related constructs.

Currently, there is no available self-report participation measure for use with young people with CP that captures Attendance and Involvement across a range of age-appropriate life domains that includes accessible design features. A new participation measure that has the potential to fill this gap, is the Picture my Participation (PMP) measure [Citation78]. The PMP (English version) did not meet the inclusion criteria for this systematic review as it has not yet been utilised with young people with CP in published studies. However, the PMP is proving to be a valid and reliable measure of Attendance and Involvement for young people with disabilities. The PMP is a self-reported participation measure for people aged 5–21 years, which utilises Picture Communication Symbols (PCS) [Citation71] to engage participants with a range of abilities to report on Attendance and Involvement across life situations [Citation78]. The Wheelchair Outcome Measure for Young People (WhOM-YP) is another example of a measure which uses accessible design features to capture the importance and satisfaction of participation outcomes via self-report [Citation79]. Further work is needed to co-develop appropriate measures with accessible design features for young people with CP.

Based on the results from this systematic review we have developed a decision-making tool to assist clinicians and researchers with the selection of participation-focused measures for use with young people with CP (Supplementary Appendix 4). This tool is designed with a stepwise decision-making structure covering: (i) measurement areas of either Attendance only, or Attendance and Involvement; (ii) response mode, including self-report only, or self-report and/or proxy-report; and (iii) ICF domain content and utility considerations such as intended age range, administration time, and if there are any accessible design features such as graphics or illustrations. Available psychometric data is graphed underneath each measure. Collectively, the tool illustrates the breadth of measures, the ratio of measures addressing Attendance versus Involvement, the current state of psychometric evidence, and measures in need of future research. Supplementary Appendix 4 also provides another useful resource which outlines examples of how rating scales used in the measures can be mapped according to the fPRC participation-focused or participation-related constructs.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include using the COSMIN checklist and level of evidence guide to provide the strength of validity, reliability, and responsiveness data when used with young people with CP. This review has also contributed valuable input into addressing the complexities of measuring the participation construct, by mapping the measures to both the ICF and fPRC to enable clinicians and researchers to identify not only which domains are being measured (ICF life domains) but also how they are being measured (fPRC constructs). The clinical decision-making tool and fPRC mapping example (Supplementary Appendix 4) summarises this information in a rapid and accessible format to support researchers and clinicians. Another strength of this review is the consideration and reporting of participation by young people with communication support needs in both measure design and psychometric research, as this is a population that is often excluded from both processes.

There were some limitations in this systematic review. To gather information on accessible design features we reviewed data from the included papers, manuals, and measure pages (where available). Other included measures may have accessible design features, but this was not explicitly stated in the available documents. Only papers published on English versions of measures were included. There may be additional measures in languages other than English that could be considered. Finally, this review only reflects what has been reported in the literature and does not capture the actual practices of clinicians with their clients. It would be beneficial for future research to explore which of these measures are being clinically utilised.

Conclusion

Research into the participation of young people with CP is still emerging and further work is needed to develop the level of evidence available to support the use of participation-focused measures with this population. Few included studies reported using self-report of people with communication support needs and further work is required to adapt participation measures to enable accessible self-report. This systematic review provides a useful clinical decision-making tool (Supplementary Appendix 4) to assist clinicians and researchers when choosing between the available participation-focused measures when working with young people with CP during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (3 MB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (198.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (148.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Participation measures accessed for the purpose of this review were retrieved by either accessing them online or by contacting the measure authors for access to the measure.

The SEAS measure was accessed under license from Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto. The access of the PEM-CY measure (authored by W. Coster, M. Law, and G. Bedell) and the APS measure (authored by H. Bourke-Taylor, M. Law, L. Howie, and J.F. Pallant) were under license from McMaster University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(s109):8–14.

- Reddihough DS, Jiang B, Lanigan A, et al. Social outcomes of young adults with cerebral palsy. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;38(3):215–222.

- World Health Organization. ICF: international classification of functioning, disability and health/World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Badawi N, Honan I, Finch-Edmondson M, et al. The Australian & New Zealand cerebral palsy strategy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(8):885.

- Adair B, Ullenhag A, Rosenbaum P, et al. Measures used to quantify participation in childhood disability and their alignment with the family of participation-related constructs: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(11):1101–1116.

- Field DA, Miller WC, Ryan SE, et al. Measuring participation for children and youth with power mobility needs: a systematic review of potential health measurement tools. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):462.e40–477.e40.

- Pashmdarfard M, Mirzakhani Araghi N. Participation assessment scales for 4 to 18-year-old individuals with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. IRJ. 2022;20(2):127–138.

- Rainey L, van Nispen R, van der Zee C, et al. Measurement properties of questionnaires assessing participation in children and adolescents with a disability: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(10):2793–2808.

- Resch C, Van Kruijsbergen M, Ketelaar M, et al. Assessing participation of children with acquired brain injury and cerebral palsy: a systematic review of measurement properties. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(4):434–444.

- Rozkalne Z, Bertule D. Measurement of activities and participation for children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. SHS Web Conf. 2014;10:00038.

- Sakzewski L, Boyd R, Ziviani J. Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5- to 13-year-old children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(3):232–240.

- Schiariti V, Klassen AF, Cieza A, et al. Comparing contents of outcome measures in cerebral palsy using the international classification of functioning (ICF-CY): a systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(1):1–12.

- Benner JL, Noten S, Limsakul C, et al. Outcomes in adults with cerebral palsy: systematic review using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(10):1153–1161.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(1):16–25.

- Eyssen IC, Steultjens MP, Dekker J, et al. A systematic review of instruments assessing participation: challenges in defining participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):983–997.

- Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP. Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concerning participation and environmental factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11 Suppl):S22–S35.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, et al. ‘Participation’: a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(1):29–38.

- Imms C, Green D. Participation: optimising outcomes in childhood-onset neurodisability. London: Mac Keith Press; 2020.

- Maxwell G, Alves I, Granlund M. Participation and environmental aspects in education and the ICF and the ICF-CY: findings from a systematic literature review. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15(1):63–78.

- Offer D, Schonert-Reichl K, Boxer A. Normal adolescent development: empirical research findings. Child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. New York: Wolters Kluwer; 1996. p. 280–290.

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480.

- Bagatell N, Chan D, Rauch KK, et al. “Thrust into adulthood”: transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(1):80–86.

- Jacobson D, Löwing K, Hjalmarsson E, et al. Exploring social participation in young adults with cerebral palsy. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(3):167–174.

- Schmidt AK, van Gorp M, van Wely L, et al. Autonomy in participation in cerebral palsy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(3):363–371.

- Lami F, Egberts K, Ure A, et al. Measurement properties of instruments that assess participation in young people with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(3):230–243.

- Taylor-Roberts L, Strohmaier S, Jones F, et al. A systematic review of community participation measures for people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(3):706–718.

- Noonan VK, Miller WC, Noreau L. A review of instruments assessing participation in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47(6):435–446.

- Dalemans R, de Witte LP, Lemmens J, et al. Measures for rating social participation in people with aphasia: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(6):542–555.

- Büğüşan S, Kahraman A, Elbasan B, et al. Do adolescents with cerebral palsy agree with their caregivers on their participation and quality of life? Disabil Health J. 2018;11(2):287–292.

- Waters E, Stewart-Brown S, Fitzpatrick R. Agreement between adolescent self-report and parent reports of health and well-being: results of an epidemiological study. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(6):501–509.

- Ison NL. Having their say: email interviews for research data collection with people who have verbal communication impairment. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2009;12(2):161–172.

- Jahnsen R, Ramstad K, Myklebust G, et al. Independence of young people with cerebral palsy during transition to adulthood: a population-based 3 year follow-up study. J Transit Med. 2020;2(1):1–12.

- Cockerill H, Elbourne D, Allen E, et al. Speech, communication and use of augmentative communication in young people with cerebral palsy: the SH&PE population study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(2):149–157.

- Mei C, Reilly S, Reddihough D, et al. Motor speech impairment, activity, and participation in children with cerebral palsy. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(4):427–435.

- Mei C, Reilly S, Reddihough D, et al. Language outcomes of children with cerebral palsy aged 5 years and 6 years: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(6):605–611.

- Nordberg A, Miniscalco C, Lohmander A, et al. Speech problems affect more than one in two children with cerebral palsy: Swedish population-based study. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(2):161–166.

- Scholderle T, Staiger A, Lampe R, et al. Dysarthria in adults with cerebral palsy: clinical presentation and impacts on communication. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2016;59(2):216–229.

- Vos RC, Dallmeijer AJ, Verhoef M, et al. Developmental trajectories of receptive and expressive communication in children and young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(10):951–959.

- ACPR Group. Report of the Australian Cerebral Palsy Register Birth Years 1995–2016. 2023.

- Law J, van der Gaag A, Hardcastle WJ, et al. Communication support needs: a review of the literature. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Social Research; 2007.

- Speech Pathology Australia. Communication access literature review report. Melbourne, Australia: Speech Pathology Australia; 2018.

- Tetley A, Jinks M, Huband N, et al. A systematic review of measures of therapeutic engagement in psychosocial and psychological treatment. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(9):927–941.

- Walton H, Spector A, Tombor I, et al. Measures of fidelity of delivery of, and engagement with, complex, face-to-face health behaviour change interventions: a systematic review of measure quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):872–903.

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):212–218.

- Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, et al. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):574–583.

- Ballert CS, Hopfe M, Kus S, et al. Using the refined ICF linking rules to compare the content of existing instruments and assessments: a systematic review and exemplary analysis of instruments measuring participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):584–600.

- Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1171–1179.

- Mokkink LB, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, et al. COSMIN study design checklist for patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2019:1–32.

- Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):651–657.

- Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42.

- Andreopoulou G, Mercer TH, van der Linden ML. Walking measures to evaluate assistive technology for foot drop in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of psychometric properties. Gait Posture. 2018;61:55–66.

- Schellingerhout J, Verhagen A, Heymans MW, et al. Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):659–670.

- van Tulder MW, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003;28(12):1290–1299.

- Goo M, Tucker K, Johnston LM. Muscle tone assessments for children aged 0 to 12 years: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(7):660–671.

- Goo M, Johnston LM, Hug F, et al. Systematic review of instrumented measures of skeletal muscle mechanical properties: evidence for the application of shear wave elastography with children. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(8):1831–1840.

- Hanratty J, Livingstone N, Robalino S, et al. Systematic review of the measurement properties of tools used to measure behaviour problems in young children with autism. PLOS One. 2015;10(12):e0144649.

- Saether R, Helbostad JL, Riphagen II, et al. Clinical tools to assess balance in children and adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(11):988–999.

- Communication Resource Centre. Scope’s accessible information service: what is easy English: scope; 2015 [cited 2022 May 20]. Available from: https://shop.scopeaust.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/what-is-easy-english.pdf

- McDougall J, Bedell G, Wright V. The youth report version of the child and adolescent scale of participation (CASP): assessment of psychometric properties and comparison with parent report. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(4):512–522.

- Bedell G. Further validation of the child and adolescent scale of participation (CASP). Dev Neurorehabil. 2009;12(5):342–351.

- King G, Law M, King S, et al. Children’s assessment of participation and enjoyment (CAPE) and preferences for activities of children (PAC). Manual San Anotnio (TX): Harcourt Assessment, Inc; 2004.

- Munger ME, Aldahondo N, Krach LE, et al. Long-term outcomes after selective dorsal rhizotomy: a retrospective matched cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(11):1196–1203.

- Boyer ER, Stout JL, Laine JC, et al. Long-term outcomes of distal femoral extension osteotomy and patellar tendon advancement in individuals with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(1):31–41.

- Coster W, Bedell G, Law M, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the participation and environment measure for children and youth. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(11):1030–1037.

- Armstrong EL, Boyd RN, Horan SA, et al. Functional electrical stimulation cycling, goal-directed training, and adapted cycling for children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(12):1406–1413.

- Gray DB, Hollingsworth HH, Stark SL, et al. Participation survey/mobility: psychometric properties of a measure of participation for people with mobility impairments and limitations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(2):189–197.

- Tuffrey C, Bateman BJ, Colver AC. The questionnaire of young people’s participation (QYPP): a new measure of participation frequency for disabled young people. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(4):500–511.

- Michelsen SI, Flachs EM, Damsgaard MT, et al. European study of frequency of participation of adolescents with and without cerebral palsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(3):282–294.

- King G, Batorowicz B, Rigby P, et al. The leisure activity settings and experiences of youth with severe disabilities. Dev Neurorehabil. 2014;17(4):259–269.

- King G, Batorowicz B, Rigby P, et al. Development of a measure to assess youth self-reported experiences of activity settings (SEAS). Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2014;61(1):44–66.

- Jonson R. Picture communication symbols. Solana Beach: Mayer-Johnson. 1985.

- Batorowicz B, King G, Vane F, et al. Exploring validation of a graphic symbol questionnaire to measure participation experiences of youth in activity settings. Augment Altern Commun. 2017;33(2):97–109.

- Chagas PSC, Magalhães EDD, Junior S, et al. Development of children, adolescents, and young adults with cerebral palsy according to the ICF: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022:1–9. DOI:10.1111/dmcn.15484

- Sellwood D, Raghavendra P, Walker R. Facilitators and barriers to developing romantic and sexual relationships: lived experiences of people with complex communication needs. Augment Altern Commun. 2022;38(1):1–14.

- Towns M, Lindsay S, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, et al. Balance confidence and physical activity participation of independently ambulatory youth with cerebral palsy: an exploration of youths’ and parents’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(11):2305–2316.

- Shikako-Thomas K, Shevell M, Lach L, et al. Are you doing what you want to do? Leisure preferences of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2015;18(4):234–240.

- King G, Rigby P, Batorowicz B, et al. Development of a direct observation measure of environmental qualities of activity settings. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(8):763–769.

- Arvidsson P, Dada S, Granlund M, et al. Content validity and usefulness of Picture My Participation for measuring participation in children with and without intellectual disability in South Africa and Sweden. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(5):336–348.

- Field DA, Miller WC. The wheelchair outcome measure for young people (WhOM-YP): modification and metrics for children and youth with mobility limitations. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2022;17(2):192–200.

- Bedell GM. Developing a follow-up survey focused on participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. NRE. 2004;19(3):191–205.

- Michelsen SI, Flachs EM, Uldall P, et al. Frequency of participation of 8–12-year-old children with cerebral palsy: a multi-centre cross-sectional European study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13(2):165–177.

- Coster W, Law M, Bedell G, et al. Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(3):238–246.

- Cleary SL, Taylor NF, Dodd KJ, et al. An aerobic exercise program for young people with cerebral palsy in specialist schools: a phase I randomized controlled trial. Dev Neurorehabil. 2017;20(6):331–338.

- Imms C, Adair B. Participation trajectories: impact of school transitions on children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(2):174–182.

- Kang LJ, Palisano RJ, Orlin MN, et al. Determinants of social participation-with friends and others who are not family members-for youths with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2010;90(12):1743–1757.

- Kang LJ, Palisano RJ, King GA, et al. Social participation of youths with cerebral palsy differed based on their self-perceived competence as a friend. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(1):117–127.

- King GA, Law M, King S, et al. Measuring children’s participation in recreation and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33(1):28–39.

- King G, Imms C, Palisano R, et al. Geographical patterns in the recreation and leisure participation of children and youth with cerebral palsy: a CAPE international collaborative network study. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16(3):196–206.

- Palisano RJ, Kang LJ, Chiarello LA, et al. Social and community participation of children and youth with cerebral palsy is associated with age and gross motor function classification. Phys Ther. 2009;89(12):1304–1314.

- Palisano RJ, Orlin M, Chiarello LA, et al. Determinants of intensity of participation in leisure and recreational activities by youth with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(9):1468–1476.

- Shikako-Thomas K, Shevell M, Schmitz N, et al. Determinants of participation in leisure activities among adolescents with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(9):2621–2634.

- Shikako-Thomas K, Shevell M, Lach L, et al. Picture me playing-a portrait of participation and enjoyment of leisure activities in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(3):1001–1010.

- Bedell G, Coster W, Law M, et al. Community participation, supports, and barriers of school-age children with and without disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(2):315–323.

- Khetani M, Marley J, Baker M, et al. Validity of the participation and environment measure for children and youth (PEM-CY) for health impact assessment (HIA) in sustainable development projects. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(2):226–235.

- Mitchell LE, Ziviani J, Boyd RN. Characteristics associated with physical activity among independently ambulant children and adolescents with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(2):167–174.

- Zeidan J, Joseph L, Camden C, et al. Look around me: environmental and socio-economic factors related to community participation for children with cerebral palsy in québec. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2020;41(4):1–18.