Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to investigate whether the treatment effects, in terms of goal attainment, transfer effects and impact on executive functions, of an intervention in children with cerebral palsy or spina bifida using the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) Approach are maintained over time, from immediately after the intervention to three months afterwards.

Method

A three-month follow-up study, from an intervention using CO-OP. Thirty-four children (7–16 years) each identified four goals (one untrained to examine transfer) and participated in an eleven-session intervention. Assessments were performed at baseline, immediately after the intervention and at a three-month follow-up using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure and the Performance Quality Rating Scale. Executive function and self-rated competence were assessed at the same timepoints.

Results

Statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements in goal achievement were demonstrated for both trained and untrained goals after the intervention and were maintained at follow-up. The clinically relevant improvement in untrained goals continued to increase until follow-up. Self-rated competence increased after the intervention and was maintained at follow-up.

Conclusion

The CO-OP intervention was effective in achieving and maintaining the children’s own goals over time. The transfer effect was confirmed by higher goal attainment for the untrained goals.

Implications for rehabilitation

The children’s self-defined goals were achieved after the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) intervention and remained so at the three-month follow-up.

The CO-OP Approach is useful for children with cerebral palsy or spina bifida.

A transfer effect was demonstrated for untrained goals by both subjective and objective assessments.

Using children’s self-defined goals is effective.

Introduction

One important aspect of rehabilitation interventions in children with disabilities is that the results of those interventions should be sustainable: the effects of the intervention should continue to benefit the child over time [Citation1]. Further, after an intervention, the child should be able to perform the targeted activity in daily life. Ideally, the child should also be able to perform new skills as a result of learning the targeted activity; this is referred to as a transfer of skills [Citation2].

There is strong evidence for the benefits of using task-oriented approaches with clear goals in the rehabilitation of children with disabilities [Citation3–7]. However, most such approaches do not explicitly target the transfer of skills, since each task tends to be trained separately [Citation1]. For this reason, those approaches may not prepare children to solve other activity problems that they may encounter. Given the importance of minimising the time spent by children in therapy and of limiting the costs of care associated with recurrent visits, this could be seen as a limitation of such approaches [Citation7]. When evaluating interventions, it is, therefore, crucial to investigate whether their effects are maintained over time and whether there are transfer effects.

For decades, it has been argued that people in general, and children in particular, tend to engage in learning by doing [Citation8–11]: they typically learn a new skill best by trying to perform it and by correcting themselves until it works. However, this presupposes the ability to analyse one’s behaviour and to self-correct. Not everyone has that ability; for example, people with executive dysfunctions have problems with correcting themselves and finding new strategies [Citation12,Citation13].

One task-oriented approach to skills acquisition that both includes a focus on the transfer and addresses the issue of difficulties with learning by doing is the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) ApproachTM [Citation14,Citation15]. In CO-OP, the transfer is defined as “occurring when learning one skill influences the learning of a new skill, allowing the learner to draw on previous experiences to perform new skills” [Citation14, p. 31]. CO-OP is a generic, multi-faceted, client-centred, goal- and performance-based approach that promotes the use of cognitive strategies in new situations [Citation15]. Designed to enable occupational performance in different life situations, CO-OP enhances a person’s meta-cognitive thinking by means of a guiding process involving interaction between the therapist and the individual. In other words: rather than letting individuals learn by doing as best they can on their own, CO-OP is based on the assumption that cognitive ability is important for the process of doing and that skills development happens when the individual becomes involved in, and gains an understanding of, the process [Citation16]. CO-OP uses a collaborative learning process where individuals are asked reflective questions to help them find the path that is best suited to helping them reach their goals. As part of this interactive process, the individuals identify cognitive strategies for problem-solving during the occupational performance to succeed in reaching the goal. The therapist does not give explicit feedback but asks questions. The purpose of these questions is to enable the individuals both to reflect on their own performance and to draw up, on their own, new plans for their performance.

Studies using CO-OP in relation to persons with executive dysfunction associated with traumatic brain injury or stroke have shown that cognitive strategies can be a tool enabling them to solve activity problems on their own [Citation17–19]. Recent research has shown that children with cerebral palsy (CP) or spina bifida (SB) often have difficulties in executive functioning [Citation20–27], and there is growing evidence suggesting that the CO-OP Approach may be an effective treatment method for people with CP or SB [Citation28–34]. However, few previous studies have investigated to what extent direct treatment effects and transfer effects are maintained over time [Citation28–Citation30,Citation35]. The first report from a recent RCT study showed that CO-OP was more effective than ordinary treatment in terms of children with these conditions reaching goals and solving problems in new situations, but no follow-up data were presented [Citation33]. This study aims to investigate whether the treatment effects, in terms of goal attainment, transfer effects and impact on executive functions, of an intervention in children with CP or SB using the CO-OP Approach are maintained over time, from immediately after the intervention to three months later.

Methods

Design

This is a follow-up of a multi-centre, randomised, controlled, cross-over clinical intervention trial of the effects of CO-OP in children with CP or SB. The first report presented results from baseline to post-treatment for a CO-OP group and a control group [Citation33]. This report presents follow-up data for a larger group of children having received a CO-OP intervention. No control group is reported here since the members of the control group were subsequently given the intervention. Ethical approval was obtained prior to the study (Ref. No.: 323-16). The trial was registered in the national research web (study record: 214861) prior to enrolment and in the international ISRCTN registry (study record: 12888658) during the study process before data collection was completed.

Participants

The present study included 34 children. The inclusion criteria were children (aged 8–16 years) with CP at Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level I–III [Citation36] and Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level I–IV [Citation37] or with SB, with or without hydrocephalus, and all levels of ambulation according to the Hoffer scale [Citation38]. The children had to follow the mainstream curriculum at compulsory school, and they had to be able to formulate their own goals and communicate orally in Swedish. Of the 34 children included, 25 had been diagnosed with CP and 9 with SB ().

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

In the previous RCT study, children with either diagnosis who met all inclusion criteria were identified in medical records from the paediatric rehabilitation centres in four different geographical regions of Sweden [Citation33]. All children with one of the two diagnoses in selected municipalities, both rural and urban, in the four regions, were identified and invited to participate in the study through a letter with information. Those who had given their consent were interviewed at the time of the initial assessment appointment to clarify whether they or their parents perceived them to have problems performing or organising activities as a consequence of perceived difficulties with initiative, planning, problem-solving and decision-making. Of the participants in the present study, 21 belonged to the CO-OP group in the RCT study while 13 were included in the control group there, received treatment as usual for three months [Citation33] and were then invited to receive CO-OP treatment. Among the members of the initial control group, four children chose to decline the offer of CO-OP treatment after their control period. The mean age of the participants at T1 was 12 y 5 m (SD 2 y 3 m) ().

The parents and those children who were 15 years old or older gave their written consent to participate while children aged below 15 years received a separate information letter and gave their consent through their parents.

Intervention and procedure

Data collection started in August 2017 and ended in June 2020. All children received a CO-OP intervention encompassing eleven sessions, on average once a week, in accordance with the established CO-OP format [Citation15,Citation39]. Of the total 374 sessions, the majority took place in the child’s natural environment, wherever the activity in question usually occurred – at home, at school or in the community. A minority of the sessions took place at the child’s rehabilitation centre. Only a few sessions (n = 7) were carried out as telerehabilitation owing to participants’ time constraints or temporary illness. Prior to the first session, each child identified four self-chosen performance goals (Appendix 1) and rated, as part of baseline assessment, his or her own ability to perform those goals using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation40] scale. One of the goals was randomly selected to stay untrained during the intervention, to enable the study of transfer effects. The untrained goal was selected as follows: (1) Each child freely chose one of the four goals; this was intended to make sure that the children would remain motivated for the intervention. (2) The assessor chose one of the remaining three goals. (3) Finally, the child selected the goal that was to remain untrained by picking one of two sealed envelopes. In previous studies of CO-OP, trained and untrained goals are a common way to distinguish between the trained goals, i.e., the goals that were focused on during the intervention, and the untrained goal that was not focused on during the intervention [Citation17,Citation18,Citation33,Citation41]. In this article, we use these formulations.

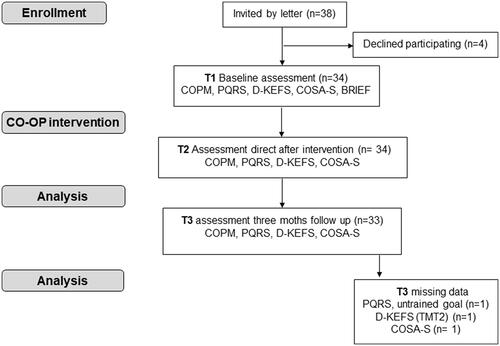

In the first session, the therapist (a) presented the CO-OP Approach and explained the global problem-solving strategy of ‘goal–plan–do–check’, to be used in the ten subsequent sessions, and (b) made video recordings to establish an objective observed baseline for the child’s performance of each activity chosen as a goal. The children’s performance of the activities was also video-recorded immediately after the end of their eleventh and final training session as well as three months after the end of treatment. The children were encouraged to use their plans between the CO-OP sessions to perform the targeted activities at home, with support from parents or significant others who had received information about the CO-OP approach, see the flow chart in .

Figure 1. Flow chart showing the children invited and the participants recruited, the number of participants assessed at baseline and immediately after the CO-OP intervention and at the 3-month follow-up.

Outcome measures

All outcome measures were administered at baseline (T1), immediately after the CO-OP intervention period (T2) and three months after that period (T3) (). The following outcome measures were used:

Goal attainment

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation40,Citation42] and the Performance Quality Rating Scale (PQRS) [Citation43] were used to assess the attainment of both trained and untrained goals. COPM is a self-rating instrument where the child rates his or her performance and satisfaction with performance on two ten-point scales (Visual Analogue Scales, VAS) [Citation44]. A higher score indicates the better self-rated performance of the identified goal and greater satisfaction with performance, respectively; a change of ≥ 2 points is considered clinically relevant [Citation40]. PQRS is a rating made by an observing therapist, based on both task completion and performance quality [Citation43]. PQRS uses a ten-point scale where higher scores reflect more efficient performance. As for COPM, a change of ≥ 2 points is considered clinically relevant [Citation29]. In the present study, ratings were based on observation of video recordings of performance by a therapist who was blinded to the chronological order of the recordings.

Transfer effects

COPM and PQRS were also used to study transfer effects in terms of changes in goal attainment for the untrained goal [Citation28–30,Citation35]. Further, the Competence scale of the Child Occupation Self-Assessment, Swedish version (COSA-S) [Citation45,Citation46] was used to study subjective transfer effects, measured as the change in self-perceived competence in the performance of generic daily-life activities. COSA-S consists of 25 items covering daily-life activities at school, at home and in the community. It has two scales, a Competence scale and a Value scale. In the present study, the Value scale was not used as an outcome measure, only utilised at baseline to facilitate goal setting by identifying areas of great value to the child.

Finally, to study possible transfer effects on executive functions, five sub-tests from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) [Citation47] were administered. Two of those sub-tests were intended to measure attention: Trail Making Test 2 (number sequencing) and Trail Making Test 4 (letter and number sequencing); two of them targeted verbal production: the Verbal Fluency Test and the Semantic Fluency Test; and the fifth one focused on planning and problem-solving: the Tower Test [Citation47]. A further tool, the Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) [Citation48], was also administered to study the potential enhancement of self- or parent-reported executive functions, which might reflect a transfer effect of CO-OP. Both the child and the parent were asked to fill in the BRIEF form at home and return it to the clinic in a stamped envelope. However, since the response rate for BRIEF was low both at baseline and at follow-up, making long-term analyses less reliable, no BRIEF results are presented in the present study. Both D-KEFS and BRIEF are widely used for children with CP or SB [Citation20,Citation25,Citation27,Citation49,Citation50).

Data analysis

SPSS version 26 was used for all data analysis. Given the ordinal nature of the COPM, PQRS and COSA-S data and the fact that a normal distribution could not be expected for all D-KEFS sub-tests, non-parametric statistical methods were used. The significance level was set to p ≤ 0.05.

In order to analyse the long-term effects of the intervention for each participant between T1, T2 and T3, the Friedman non-parametric repeated-measure test for paired samples was used for trained as well as untrained goals. For the trained goals, the means of the three COPM and three PQRS ratings for each individual were calculated separately for the three trained goals at T1, T2 and T3 and used in the analyses. Also, descriptive analyses were carried out to calculate, for each individual, the number of goals that had a clinically relevant change of ≥ 2 points, for both subjective and objective ratings of trained and untrained goals.

The median differences in ratings between T1 and T2, between T1 and T3 and between T2 and T3 were calculated for each goal, for both COPM and PQRS.

D-KEFS raw scores were transformed into age-related standardised scaled scores (m = 10, SD = 3) [Citation47]. The Friedman test was also used to study changes over time in scores on the D-KEFS sub-tests used to measure neuropsychological aspects.

The COSA-S competence ratings were analysed descriptively. First, the Percentage of Maximum Possible Score (POMP) was calculated [Citation45,Citation51]; a higher POMP indicates higher self-perceived competence. Then the relative numbers of participants who changed to a higher or lower POMP or remained at the same POMP level were calculated for T1–T2, T2–T3 and T1–T3. A change in POMP was deemed to have taken place when there was a change of at least ± 1% [Citation51].

Results

All 34 participating children completed the CO-OP intervention and the assessments at T1 and T2. However, for medical reasons, one of them did not attend the three-month follow-up at T3. Further, one of the 33 children who attended the follow-up was not assessed using PQRS for the untrained goal, since that child did not wish to have that goal video-recorded at T3. Further, the same child also did not participate in TMT2 (sub-test of D-KEFS) at T3. Another child did not complete the COSA-S interview at T3. All of the children with an incomplete assessment at T3 had been diagnosed with CP.

Goal attainment – the children’s performance for trained goals

Subjective ratings - COPM

Comparison using the repeated-measure test (Friedman test) showed a significant improvement in performance between T1 and T2 (p < 0.001) as well as between T1 and T3 (p < 0.001) (). Between T2 and T3, this improvement was maintained (non-significant changes, p = 1.00; see ).

Table 2. Goal achievement after CO-OP intervention; pairwise comparison of children’s three trained goals and the untrained goal between timepoints T1, T2 and T3, n = 33.

The median difference in COPM ratings of performance for trained goals was 5 points (on the 10-point scale) between T1 and T3, which is slightly more than the corresponding median difference between T1 and T2 (4.5 points).

Number of children reaching a clinically relevant improvement

Immediately after the intervention, 30 out of 34 children had achieved a clinically relevant improvement of ≥ 2 COPM points (T1–T2) for two or all three trained goals. At follow-up three months later, 31 out of 33 children had achieved such a clinically relevant improvement (T1–T3) ().

Table 3. Number of children with a clinically relevant increase in at least two or all three trained goals and in their untrained goal, immediately after the intervention and at follow-up after three months.

Objective ratings- PQRS

Similarly, the objective assessment using PQRS of the children’s performance on the three trained goals at the three assessment times showed a significant difference between T1 and T2 (p < 0.001) and between T1 and T3 (p < 0.001), and the improvement relative to T1 found at T2 was maintained at T3 (non-significant changes, p = 1.00; see ). A median difference of 5 points was found for trained goals between T1 and T2 as well as between T1 and T3.

Number of children reaching a clinically relevant improvement

According to the objective PQRS ratings, 30 out of 34 children achieved a clinically relevant improvement of ≥ 2 COPM points on two or more of their three trained goals immediately after the intervention (T1–T2), while 29 out of 33 children did so at follow-up (T1–T3) ().

Goal attainment – transfer to the untrained goal

Subjective ratings – COPM

A transfer effect was demonstrated such that there was a significant difference in the children’s subjective ratings of their performance of their untrained goal (one per child) from baseline (T1) to post-intervention (T2) (p = 0.003); this difference relative to T1 persisted at follow-up (T3), with a slight increase in significance (p < 0.001) ().

Ratings were stable between T2 and T3: there was no significant difference (p = 0.471) (). The median difference between T1 and T2 and between T1 and T3 was 2 and 3 points, respectively.

Number of children reaching a clinically relevant improvement

For the untrained goal, a clinically relevant improvement of ≥ 2 COPM points was achieved by 20 out of 34 children post-intervention (T1–T2) and by 28 out of 32 at follow-up (T1–T3) ().

Objective ratings – PQRS

A significant difference was also seen for the objective ratings made using PQRS of the children’s performance of their untrained goals, both between baseline (T1) and immediately after the intervention (T2) (p = 0.005) and between baseline (T1) and the three-month follow-up (T3) (p < 0.001). No significant difference was seen between T2 and T3 (p = 1.00) (). The median difference was 2 points both between T1 and T2 and between T1 and T3; hence the medians were stable between T2 and T3.

Number of children reaching a clinically relevant improvement

The objective ratings of untrained goals showed that 19 out of 34 children achieved clinically relevant improvements of ≥ 2 COPM points in their untrained goal immediately after the intervention and that 23 out of 33 children did so at follow-up ().

The children’s satisfaction with their goal attainment

The children’s ratings of their satisfaction (COPM) with their performance of the trained goals showed a significant difference between T1 and T2 which persisted at T3 ().

For the trained goals, the median difference was 5 points both between T1 and T2 and between T1 and T3. For the untrained goals, the median difference was 4 points both between T1 and T2 and between T1 and T3.

Measures of executive function

The children improved significantly in their ability to pay attention and focus (TMT2) between T1 and T3 (p = 0.003, ). Their planning ability, as measured by the Tower Test, also improved between T1 and T2 (p = 0.049) and between T1 and T3 (p = 0.049).

Table 4. Tests of executive function: results from the Friedman test, pairwise comparisons T1–T2, T1–T3 and T2–T3 for Trail making Test 2 (TMT 2) and the Tower Test.

By contrast, the children’s scores on the other executive tests – TMT4, Verbal Fluency and Semantic Fluency – showed no significant change between T1 and T2 or between T1 and T3.

The children’s perception of their competence in daily living

The descriptive analysis of the COSA-S scores showed that 22 out of 32 children rated their competence in daily life higher immediately after the CO-OP intervention period (T2) than at baseline (T1), with a higher POMP – indicating a higher self-rated competence. Further, at the three-month follow-up (T3), 23 out of 32 participants had a higher POMP than they had had at baseline (T1) and 8 children rated below baseline ().

Table 5. Children’s (n = 32) ratings on the COSA-S competence scale, compared between T1–T2 and T1–T3.

Discussion

The longitudinal analysis presented in this study suggests that the children were able to transfer a global cognitive strategy to new situations after the CO-OP intervention. The outcome in goal achievement from a period of intervention using the CO-OP Approach was maintained and even enhanced during the three months after that intervention. The results also show that there was a clear transfer effect – which was even stronger at the three-month follow-up – in the form of increased self-perceived as well as observed goal achievement for the children’s untrained goal. In addition, the children’s self-rated competence in general activities of daily living increased after the intervention and was maintained at follow-up. Among the aspects of executive function examined, only the ability to plan and solve problems and the ability to pay attention improved, but those improvements remained stable over time. These results suggest that the CO-OP Approach had a sustainable effect on children with CP and SB.

Previous studies have shown good results for CO-OP in terms of goal achievement for children with CP [Citation28–31], and this study – including the first report [Citation33] – shows that CO-OP is highly effective for children with SB as well.

The most interesting result from this study is that the number of children who showed a clinically relevant improvement in the untrained goal continued to increase during the three months after the intervention, according to both subjective and objective measurements. Hence there seemed to be a transfer effect that actually grew over time. This might be because the target groups in question need time to learn how to adopt the CO-OP approach in new situations, especially the meta-cognitive thinking, which is in focus throughout the intervention process with a view to transfer effects. However, this noteworthy increase in the achievement of the children’s goals was not accompanied by a further increase in their measurable planning and problem-solving ability as measured using the Tower Test in D-KEFS after they had completed their training. This can be interpreted as suggesting that the children increased their ability to handle their performance difficulties in real life although their measurable executive abilities did not continue to increase. Such a finding is consistent with a previous study of CO-OP in children with hyperkinetic movement disorders, whose results included improvements in goal attainment, self-efficacy and quality of life but no change in impairment-related measures [Citation30]. Another interesting finding is that scores on the executive tests regarding focus and attention increased during the intervention. The improved focus and attention may have influenced the children’s ability to reach their goals by making them able to engage longer in an activity and to be more focused on their plan to perform that activity.

CO-OP is based on a period of intensive training. The ten or eleven weeks involved may seem to consume extensive resources, but – although no health-economic measures have been presented in this study – we would argue that, if children increase their sense of competence and even achieve an increasing number of untrained goals, this potentially means that they can handle other things in life and so may not need to practise every situation individually. Indeed, since the results of this study suggest that this may be the case, the return on the resources initially invested may turn out to be quite considerable and the effects of that investment may persist well beyond the intensive-training period. Further study of this issue from a health-economic perspective could be useful.

To understand the positive results of this study, the nature of the CO-OP method should be reviewed. Learning to engage in meta-cognitive thinking is an essential part of CO-OP, enabling children to find their own solutions, and this probably gives the children a sense of competence, leading in turn to a sense of self-efficacy. This has also been shown in previous qualitative studies [Citation52–54]. The results of this study indeed demonstrate that this sense of competence, as measured using COSA-S, increased from T1 to T2 and was maintained at T3. Perceiving themselves as competent may make children more likely to continue training and try to attain their untrained goal even after the intervention period. In fact, this sense of competence may be what enables them to work on other goals. As regards those children who rated their competence as lower after the CO-OP intervention than before it, they may have changed their perspective on their own competence by starting to apply higher standards, meaning that they will have undergone what is referred to as a ‘response shift’ by Schwarz et al. [Citation55].

Further, while participants in other studies of CO-OP have tended to work on primarily motor-based goals [Citation31,Citation35,Citation56,Citation57], the children in this study chose more complex everyday activities [in terms of the steps involved], such as preparing meals, as well as many self-management and organisational goals such as being able to hand in school assignments on time. Complex goals require the use of several different strategies [Citation58], which in and of itself may be an additional factor that not only facilitated the transfer effect seen in this study relative to the untrained goal but also contributed to the enhanced perception of competence seen over time. It is also interesting that many goals are not primarily focused on actual performance but rather on getting things done and/or daring to do something that is scary or that has caused anxiety in the past. Goals of these types have previously been reported from CO-OP interventions in adults [Citation17,Citation19] and in children with Asperger syndrome [Citation59]. In the present study, the occurrence of such goals is probably due to the broad way in which COPM and COSA-S (both Competence and Value scales) were used together in the goal-setting process.

In the rehabilitation of children with neuro-developmental disabilities, family-centred care has been the norm in many countries, including Sweden, in the past two or even three decades [Citation60–62]. This has had a positive effect, entailing a shift from a medical model where rehabilitation was controlled from the professionals’ perspective to a model empowering family members. Only a few previous studies have investigated the effectiveness of interventions related to children’s own goals [Citation63]. The results from this study – both the first report [Citation33] and the present one – show that a step further, where more attention is also paid to the child’s own opinions, is both logical and necessary. It has been shown that children as young as five years can set their own goals and work towards them over time [Citation5,Citation64]. While it is of course not the case that all decisions about what a child should learn and develop in life can be handed over to the child without adult guidance [Citation65], it is interesting to note that many of the goals chosen by the children in this study actually did not focus only on leisure and fun, as one might perhaps expect, but also on school activities, home chores and self-management. What is more, this study shows that working on the child’s own goals may enhance the child’s feeling of competence, which can be assumed to give the child a stronger sense of self-efficacy. This, in turn, may enable children to dare to try new activities, even those that they may have avoided in the past but which they need to participate in and learn to perform independently.

Study limitations

A follow-up period of three months was chosen. This might be considered a short period. The rationale for this choice was the risk of losing participants in the follow-up owing to family relocation and unforeseen medical events – and, towards the end of the study, owing to the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, this follow-up study does not include a control group, which is a limitation. The choice to offer CO-OP intervention to the children in the control group of the previous study immediately after the intervention period was made for two reasons. First, we wished to counteract the risk of losing participants in the control group. Second, the CO-OP treatment had been experienced so positively by the children receiving it and their families that we considered it unethical to deprive the control group of immediate treatment.

Conclusion

This study shows that the positive results achieved in goal attainment and in the sense of competence after an intervention with CO-OP were maintained, and even stronger, three months after the completion of a CO-OP intervention period for children with cerebral palsy and children with spina bifida. Hence the effects of the CO-OP approach would appear to be sustainable over time for these target groups. Further, the fact that this continued improvement after the end of the intervention is particularly evident for the untrained goals also indicates a clear and sustained transfer effect of CO-OP. However, since this is the first study of a CO-OP intervention including a group of children with spina bifida, it is of the utmost importance to strive for a larger study including children with spina bifida in the future, preferably on an international multi-centre basis. Finally, since CO-OP is a generic approach, it would be desirable to investigate its effectiveness in groups with other disabilities, for example in children and adults with autism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the children who participated and their parents who took part in the study. We would also like to thank the occupational therapists who carried out the CO-OP interventions and the rehabilitation centres that participated. We thank psychologist Linus Lind for conducting some of the executive-functioning assessments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Geusgens CA, Winkens I, van Heugten CM, et al. Occurrence and measurement of transfer in cognitive rehabilitation: a critical review. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(6):425–439. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0092.

- Houldin A, McEwen SE, Howell MW, et al. The cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach and transfer: a scoping review. OTJR. 2018;38(3):157–172. doi: 10.1177/1539449217736059.

- Brogren Carlberg E, Lowing K. Does goal setting in activity-focused interventions for children with cerebral palsy influence treatment outcome? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55 Suppl 4:47–54. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12307.

- Lowing K, Bexelius A, Brogren Carlberg E. Activity focused and goal directed therapy for children with cerebral palsy–do goals make a difference? Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(22):1808–1816. doi: 10.1080/09638280902822278.

- Vroland-Nordstrand K, Eliasson AC, Jacobsson H, et al. Can children identify and achieve goals for intervention? A randomized trial comparing two goal-setting approaches. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(6):589–596. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12925.

- Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(2):3. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z.

- Novak I, Honan I. Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66(3):258–273. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12573.

- Cutchin MP, Dickie V, Humphry R. Transaction versus interpretation, or transaction and interpretation? A response to Michael Barber. J Occup Sci. 2006;13(1):97–99. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2006.9686575.

- Humphry R. Young children’s occupations: explicating the dynamics of developmental processes. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(2):171–179. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.2.171.

- Humphry R, Wakeford L. An occupation-centered discussion of development and implications for practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2006;60(3):258–267. doi: 10.5014/ajot.60.3.258.

- Rogoff B, Paradise R, Arauz RM, et al. Firsthand learning through intent participation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:175–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118.

- Finnanger TG, Andersson S, Chevignard M, et al. Assessment of executive function in everyday life-psychometric properties of the Norwegian adaptation of the children’s cooking task. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:761755. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.761755.

- Vogelaar B, Resing WCM, Stad FE, et al. Is planning related to dynamic testing outcomes? Investigating the potential for learning of gifted and average-ability children. Acta Psychol. 2019;196:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2019.04.004.

- Dawson DR, McEwen SE, Polatajko HJ. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance in occupational Therapy - Using the CO-OP ApproachTM to enable participation Across lifespan. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press; 2017.

- Polatajko HJ, Mandich A. Enabling occupation in children: the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE; 2004.

- Polatajko HJ. The CO-OP twist. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010;30(4):277–279. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2010.510381.

- Dawson DR, Gaya A, Hunt A, et al. Using the cognitive orientation to occupational performance (CO-OP) with adults with executive dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76(2):115–127. doi: 10.1177/000841740907600209.

- McEwen S, Polatajko H, Baum C, et al. Combined cognitive-strategy and task-specific training improve transfer to untrained activities in subacute stroke: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(6):526–536. doi: 10.1177/1545968314558602.

- Poulin V, Korner-Bitensky N, Bherer L, et al. Comparison of two cognitive interventions for adults experiencing executive dysfunction post-stroke: a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(1):1–13. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1123303.

- Bodimeade HL, Whittingham K, Lloyd O, et al. Executive function in children and adolescents with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(10):926–933. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12195.

- Bottcher L. Children with spastic cerebral palsy, their cognitive functioning, and social participation: a review. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16(3):209–228. doi: 10.1080/09297040903559630.

- Bottcher L, Flachs EM, Uldall P. Attentional and executive impairments in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(2):e42-7–e47. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03533.x.

- Jacobson LA, Tarazi RA, McCurdy MD, et al. The Kennedy Krieger independence Scales-Spina Bifida version: a measure of executive components of self-management. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58(1):98–105. doi: 10.1037/a0031555.

- Kelly NC, Ammerman RT, Rausch JR, et al. Executive functioning and psychological adjustment in children and youth with spina bifida. Child Neuropsychol. 2012;18(5):417–431. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2011.613814.

- Piovesana AM, Ross S, Whittingham K, et al. Stability of executive functioning measures in 8–17-year-old children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;29(1):133–149. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2014.999125.

- Whittingham K, Bodimeade HL, Lloyd O, et al. Everyday psychological functioning in children with unilateral cerebral palsy: does executive functioning play a role? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(6):572–579. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12374.

- Lindquist B, Jacobsson H, Strinnholm M, et al. A scoping review of cognition in spina bifida and its consequences for activity and participation throughout life. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111(9):1682–1694. doi: 10.1111/apa.16420.

- Cameron D, Craig T, Edwards B, et al. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP): a new approach for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37(2):183–198. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2016.1185500.

- Gimeno H, Brown RG, Lin JP, et al. Cognitive approach to rehabilitation in children with hyperkinetic movement disorders post-DBS. Neurology. 2019;92(11):e1212–e24. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007092.

- Gimeno H, Polatajko HJ, Cornelius V, et al. Rehabilitation in childhood-onset hyperkinetic movement disorders including dystonia: treatment change in outcomes across the ICF and feasibility of outcomes for full trial evaluation. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2021;33:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2021.04.0091090.

- Jackman M, Novak I, Lannin N, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance over and above functional hand splints for children with cerebral palsy or brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):248. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1213-9.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M, Bergqvist L, Hofgren C, et al. Potential benefits of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach in young adults with spina bifida or cerebral palsy: a feasibility study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(2):228–239. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1496152.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M, Hofgren C, Lindquist B, et al. The cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach is superior to ordinary treatment for the achievement of goals and transfer effects in children with cerebral palsy and spina bifida - a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(5):822–831. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2043459.

- Gimeno H, Jackman M, Novak I. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) intervention for people with cerebral palsy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Pediatr Perinatol Child Health. 2021;5(3):177–193.

- Sousa LK, Brandao MB, Curtin CM, et al. A collaborative and cognitive-based intervention for young people with cerebral palsy. Can J Occup Ther. 2020;87(4):319–330. doi: 10.1177/0008417420946608.

- Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rosblad B, et al. The manual ability classification system (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(7):549–554. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206001162.

- Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, et al. Content validity of the expanded and revised gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(10):744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03089.x.

- Hoffer MM, Feiwell E, Perry R, et al. Functional ambulation in patients with myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(1):137–148. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197355010-00014.

- Polatajko HJ, Mandich AD, Missiuna C, et al. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP): part III–the protocol in brief. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2001;20(2):107–123. doi: 10.1300/J006v20n02_07.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM). 5th ed. rev. 2019 ed. Nacka: Sveriges Arbetsterapeuter; 2020.

- McEwen SE, Polatajko HJ, Huijbregts MP, et al. Inter-task transfer of meaningful, functional skills following a cognitive-based treatment: results of three multiple baseline design experiments in adults with chronic stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20(4):541–561. doi: 10.1080/09602011003638194.

- Kang M, Smith E, Goldsmith CH, et al. Documenting change with the Canadian occupational performance measure for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(10):1154–1160. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14569.

- Martini R, Rios J, Polatajko H, et al. The performance quality rating scale (PQRS): reliability, convergent validity, and internal responsiveness for two scoring systems. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(3):231–238. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.913702.

- Redke F. Smärta. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1999.

- Kramer J, ten Velden M, Kafkes A, et al. Child occupational self assessment (COSA), version 2.2 in swedish: Barns mening om aktiviteter - självskattning av kompetens och betydelse (COSA-S),. Nacka: Sveriges Arbetsterapeuter.; 2016.

- Kramer JM, Kielhofner G, Smith EV.Jr. Validity evidence for the child occupational self assessment. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(4):621–632. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2010.08142.

- Delis DC, Kaplan D, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan executive function system (D-KEFS) technical manual. Swedish version; Pearson Assessment ed. San Antonio (TX): Psychological Corporation; 2001.

- Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, et al. BRIEF behaviour rating inventory of executive functions. Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000.

- Pereira A, Lopes S, Magalhaes P, et al. How executive functions are evaluated in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy? A systematic review. Front Psychol. 2018;9:21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00021.

- Zabel TA, Jacobson LA, Zachik C, et al. Parent- and self-ratings of executive functions in adolescents and young adults with spina bifida. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25(6):926–941. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2011.586002.

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, et al. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behav Res. 1999;34(3):315–346. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3403_2.

- Jackman M, Novak I, Lannin N, et al. Parents’ experience of undertaking an intensive cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) group for children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(10):1018–1024. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1179350.

- McEwen SE, Polatajko HJ, Davis JA, et al. There’s a real plan here, and I am responsible for that plan’: participant experiences with a novel cognitive-based treatment approach for adults living with chronic stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):540–550.

- Öhrvall AM, Bergqvist L, Hofgren C, et al. With CO-OP I’m the boss" - experiences of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach as reported by young adults with cerebral palsy or spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(25):3645–3652. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1607911.

- Schwartz CE, Andresen EM, Nosek MA, et al. Response shift theory: important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.032.

- Ghorbani N, Rassafiani M, Izadi-Najafabadi S, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive orientation to (daily) occupational performance (CO-OP) on children with cerebral palsy: a mixed design. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;71:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.09.007.

- Gimeno H, Polatajko HJ, Lin JP, et al. Cognitive strategy training in childhood-onset movement disorders: replication across therapists. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:600337. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.600337.

- Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57(9):705–717. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.9.705.

- Rodger S, Vishram A. Mastering social and organization goals: strategy use by two children with Asperger syndrome during cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010;30(4):264–276. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2010.500893.

- Jeglinsky I, Autti-Rämö I, Brogren Carlberg E. Two sides of the mirror: parents’ and service providers’ view on the family-centredness of care for children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(1):79–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01305.x.

- Lammi BM, Law M. The effects of family-centred functional therapy on the occupational performance of children with cerebral palsy. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70(5):285–297. doi: 10.1177/000841740307000505.

- Law M, Teplicky R, King S, et al. Family-centred service: moving ideas into practice. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31(6):633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00568.x.

- Pritchard-Wiart L, Phelan SK. Goal setting in paediatric rehabilitation for children with motor disabilities: a scoping review. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(7):954–966. doi: 10.1177/0269215518758484.

- Vroland-Nordstrand K, Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, et al. Parents’ experiences of conducting a goal-directed intervention based on children’s self-identified goals, a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(4):243–251. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1335778.

- UnitedNations. Convention on the Rights of the Child [Internet]. United Nation 1989 Available from: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention.

Appendix 1.

Activity areas for chosen goals and examples of types of goals for children included in intervention with COOP.