Abstract

Problematic substance use (PSU) has documented consequences for the person using substances and people close to that person. This meta-ethnography aims to provide insight into how families experience family life when adult family members PSU is present. The titles and abstracts of 24,423 retrieved studies were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Fifteen qualitative primary articles, including 393 different family members experiences, were included. The included articles described families from different countries with various socioeconomic status. An unknown invisible intrusion was established as the overarching metaphor. This metaphor was accompanied by three main themes: Taking over the family life, Family survival, and An invisible family. The theme Taking over the family life reflects how PSU affected the family structures and how overwhelming the families experienced these problems. The theme Family survival reflects how family members tried to adapt to life with PSU, while An invisible family reflects how families experienced loneliness and lack of help. We suggest that professionals should move from a one-sided focus on PSU to understanding the consequences as a long-lasting intrusion into family life. This includes both disciplinary development and interventions that enhance family relational practices.

Introduction

Problematic substance use (PSU) is a complex problem associated with significant health risks and a serious threat of premature death (WHO, Citation2018). PSU is acknowledged as a serious problem for the individual family member who is using substances. Still, as Selbekk (Citation2019) points out, it is a thought-provoking paradox that disclosure of substance use problems does not directly imply disclosure of its harmful effects on close others. However, an individual's drug challenges have significant and harmful effects on close others, such as family members, who report severe and far-reaching consequences, including uncertainty, worries, stress, and difficult family life (Orford et al., Citation2010; Orr et al., Citation2014; Ray et al., Citation2007; Rodriguez et al., Citation2014). Family members of people with PSU may be especially vulnerable to repeated periods of relapses and breaks in treatment, and therefore experience increasing harm (Andersson et al., Citation2018; Edwards et al., Citation2018).

PSU is usually understood as harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances (WHO, Citation2018). In this article, we do not distinguish between the use of legal substances, such as alcohol, and the use of illegal drugs, insofar as our focus is on how families are living with consequences that may result from all types of substance-use problems. It is commonly understood that PSU has many of the characteristics of a chronic condition; PSU is, for instance, marked by cycles of recovery, ongoing use, and repeated treatments (Fleury et al., Citation2016; McKay, Citation2017; McLellan et al., Citation2000; Selseng & Ulvik, Citation2019; Sheedy & Whitter, Citation2013). There is a high and long-lasting risk for repetitive episodes of substance use. International studies show that 50–70% of patients return to using during the first year following treatment (White & Kelly, Citation2011).

PSU has overwhelming consequences for persons using substances and for close others, such as family members and friends. It is estimated that 35 million people were suffering from drug use disorders in 2017 (World Drug Report, Citation2019). In 2018, there were 67,367 deaths from drug overdoses in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2019). Most of the deaths were premature and affected people in their thirties and forties. The legal drug alcohol is responsible for more than 95,000 deaths in the United States each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2019). Like illicit drugs, alcohol takes young lives: every fifth death in the 15–19 age group was attributable to alcohol (WHO, Citation2018). Behind these figures, there are many families whose lives are profoundly affected.

The most important of our relationships is often described as being the family (Lorås & Ness, Citation2019). However, the form and organization of the family is constantly changing. While the family's function in the pre-industrial society was to a greater extent characterized by functions to ensure survival, many of the duties today are taken over by various societal institutions. Nevertheless, the family is still of great importance and takes care of people's basic needs for love, security, belonging, care, and social development (Lorås & Ness, Citation2019). Thus, there is no reason to idealize family life. The importance of the family will not imply that family life always is a good thing. Family is a powerful factor, but this power can work in many directions (Vedeler, Citation2011). The closeness and necessity of our family relationships may involve resources, protection, and a safe base for individual development. The closeness and importance make family also an arena for particular vulnerability to violations and negative experiences (Vedeler, Citation2011). The intergenerational solidarity model is a conceptual tool for understanding solidarity among parents and children during the adult family life course (Bengtson & Roberts, Citation1991). The solidarity in families is often thought of as being played out along several dimensions – socially (contact), consensually (agreement in opinions, values, and lifestyles), emotionally (emotional closeness or conflict), and functionally (mutual help). 'Normative solidarity' refers to the strength of duties and obligations felt towards other family members (Bengtson & Roberts, Citation1991; Herlofson & Daatland, Citation2016). The intergenerational solidarity model is used to model relationships between generations. The roles of grandparents, parents, and children tend to be stable over time; for example, parents usually help their children most of their lives, and the direction of help tends to remain stable until the parents reach the age of 70–75 (Herlofson & Daatland, Citation2016). The different types of relatives occupy different positions in the family, so it is important to focus on all the relationships within families, like relations to partners and siblings. It is also important to keep in mind that the modern family takes many forms. In this article, the term 'family' includes all kinds of family relations, including cohabitation and step relationships. As 'parent', we define any adult in the household who has a parental role relative to the child, she/she is biologically related or legally expected to take on the role of a parent (see WHO, Citation1996, pp. 233–234).

A family member's role and position in the family may change with age, leading to new expectations and functions. Family life-cycle theory describes common changes in family life across different stages (Carter & McGoldrick, Citation1989). At one of these stages, an adult person leaves the family home as a single adult and establishes an adult existence, often with a partner and children of their own (Carter & McGoldrick, Citation1989). In this study, family life is understood as a social process unfolding over time. Accordingly, family life is understood broadly, encompassing the everyday life of the family and everyday experiences of relations in the family, including roles, obligations, practices, emotional bonds, and communication. We decided to focus on family experiences with adult substance-using family members. We assumed that adult and young family members have different roles and expectations in families and societies.

We have aimed to look at the topic of PSU from a family perspective. The study contributes to knowledge of how substance use influences several parts of family life. Such knowledge is important to understand better what help and support families living with ongoing substance use need, especially to support their participation in long-term recovery processes. The aim of this study is to integrate and synthesize knowledge of family members' experiences of family life when an adult family member's substance use is perceived as problematic. Thus, the research question is as follows: 'What is the impact of an adult family member's problematic substance use for family life?'

Materials and methods

A meta-ethnography approach was chosen to discover new perspectives, which 'forces us to reconceptualize synthesis by providing an alternative view for the collective use of case studies’ (Doyle, Citation2003). Several meta-synthesis approaches to synthesizing qualitative studies have been developed (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009; Bondas & Hall, Citation2007a; Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007). Meta-ethnography, as developed by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988), was chosen for its potential to interpret and integrate qualitative findings in a systematic and reflective way. This review was guided by the eMERGe reporting guidance developed by France et al. (Citation2019a). The recent development of guidelines for meta-ethnography (France et al., Citation2019a; France et al., Citation2019b) was used as a complement.

Meta‐ethnography is an inductive and interpretive form of knowledge-synthesis that can lead to important new conceptual understandings of a phenomenon (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). Meta-ethnography connects and integrates the findings from different original studies through the extraction of findings, in-depth systematic comparison of similarities and differences, and translation of research studies into one another, determining relationships between translations towards a synthesis (France et al., Citation2019a; Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The approach creates the opportunity for developing new theoretical perspectives to support evidence-based practice in our contested research area. We have aimed to look at the topic of PSU and families from a new perspective. Problematic substance use (PSU) has documented consequences for the person using substances and people close to that person, but consequences for family life and family relations in the long term are not equally examined. We have, therefore, been interested in primary studies with rich descriptions of family life and family relationships. We have also been interested in studies with perspectives from both substance-using family members and family members affected by other family member's PSU.

Meta-ethnography

This study follows the seven non-linear phases of synthesis described by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988): (1) getting started, (2) deciding what is relevant to the initial interest, (3) reading the studies, (4) determining how the studies are related, (5) taking findings from one study and recognizing the same meaning in findings in another included study (what Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) refer to as 'translating the studies into one another'), (6) synthesizing translations, and (7) expressing the synthesis (Appendix I). We use three parts to structure the presentation of the method: Searches and critical appraisal (phases 1 and 2), analysis (phases 3, 4, and 5), and finally, synthesis (phases 6 and 7).

Searches and critical appraisal

Getting started

A research team was assembled to facilitate a critical and reflective research process (see Bondas & Hall, Citation2007b) . The team members had a variety of professional, methodological, and scientific backgrounds (social education, social work, nursing, caring, and health sciences), as well as diverse personal experiences.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on decisions described in the Introduction. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were according to the research question: family, next of kin, parent, child, sibling, and spouse (population); substance use (the phenomena of interest); family life (the purpose of the study or evaluation); and, qualitative research (type of research). Studies with rich descriptions of family life and family relationships were included, while studies primarily focusing on the impact of PSU on individual family members' lives and coping, without descriptions of family life, were excluded, elaborated in .

Table 1. The inclusion/exclusion criteria.

A thorough and systematic literature-search strategy based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed by the first (S. K. L.) and second author (K. B. T.) and an academic librarian (M. N. T.). An academic librarian (G. A.) peer-reviewed the electronic search strategy, and an academic librarian (M. N. T.) performed the search in April 2019 (Appendix II). An update search in the databases was performed in June 2020 (M. N. T.). Four major electronic databases – CINAHL (EBSCO) (1981-), PsycINFO (Ovid) (1806-), SocINDEX (EBSCO) (1908-), Web of Science (1950-), and the Scandinavian database SveMed + were searched. Citation, reference, and journal searches ('Journal of Substance Use', 'Substance Use & Misuse', 'Journal of Family Therapy', 'Addiction', 'Nordic Studies On Alcohol And Drugs' and Idunn (a Scandinavian digital publishing platform for academic journals and books), and searches for grey literature were completed by the first author (S. K. L.). Citation searches were completed twice, in January 2020 (S. K. L. and K. B. T.) and May 2020 (S. K. L.). Titles, abstracts, and full texts of original qualitative articles were examined, and those considered suitable according to the research objective were included.

Deciding what is relevant to the initial interest

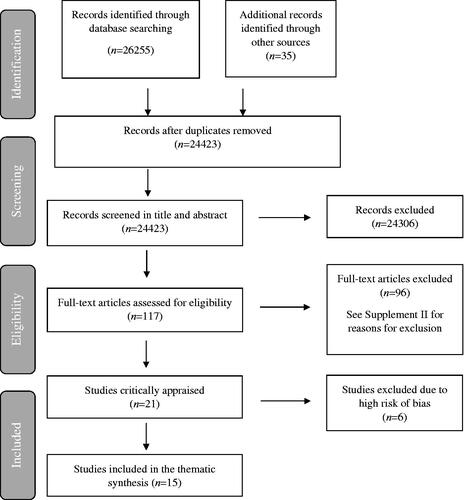

The systematic search yielded 26,255 records. Citation, reference, and journal searches gave 35 records. The selection process of the studies began with the elimination of 1867 duplicate studies. We used the PRISMA flowchart to record the inclusion and exclusion of studies in the review (). The titles and abstracts of 24,423 retrieved studies were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 117 studies were subsequently read in full text and examined in relation to the criteria. At this stage, 96 studies were excluded. At both stages, the entire selection process was executed by S. K. L. and K. B. T. All full-text articles excluded at this stage of the selection process are presented in an 'Excluded Studies' table together with the reason for exclusion (Appendix III). The CASP Checklist for qualitative research (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018) was used for critically appraising qualitative research (S. K. L. and L. L.), and six studies were excluded (Appendix IV). The other team members were consulted with respect to minor disagreements regarding a few studies, and these were easily solved by re-reading and discussion.

The final sample comprised 15 articles (). The first, third, and last author (S. K. L., L. L., and T. B.) read the full text of the 15 included studies, noting essential findings in this early phase. The articles included were from countries and families with socioeconomic differences. The included studies in this meta-ethnography presented the experiences of 393 participants: 85 parents, 137 partners and ex-partners, 26 siblings, 97 children, 5 other family members, and 49 family members using substances (23 adult sons, 17 adult daughters, 5 mothers, and 4 fathers). The studies also included six persons with double or triple roles (e.g. daughter–wife–sister). An overview of each included study and its characteristics is presented in .

Table 2. Characteristics of Included studies.

Analysis

Reading the studies

Phase 3 involved repeated reading of the included studies, taking note of interpretative metaphors, and data extraction. This phase that ends with determining the relationship between the studies is characteristic for this methodology and separates meta-ethnography from other types of qualitative synthesizing (France et al., Citation2019a).

Determining how the studies are related

After several readings and discussions within the team, we determined how the studies were related by juxtaposing the major findings (see Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The findings of the studies were found to be reciprocal or analogous, and the systematic translation process of data extraction could then begin.

Translating the studies into one another

The translation process is typical for meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988), referring to the process of translating findings from one study and recognizing them in another included study, although not expressed using identical words but searching for meaning. One seminal study that included rich findings was used at a team meeting to discuss preliminary assumptions and gain a shared understanding of the translational analysis. Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) describe the translational analysis as idiomatic rather than literal. We decided that detailed coding (France et al., Citation2019b), inspired by the 'line-by-line coding' from grounded theory (Charmaz, Citation2014), could be the most useful tool, insofar as the level of analysis varied in the studies included and we strived for theoretical development. We used matrices for overview and systematic analysis. Similarities and differences were identified and discussed when coding the findings, then sorted towards a synthesis. The team members did the data extraction and analysis independently in pairs to strengthen credibility, and the lead author cross-checked the whole process. Examples of the analysis process are presented in Appendices V and VI.

Synthesis

Synthesizing translations

When the translation process was finished, we discussed the themes and metaphors emerging from the findings. The primarily included studies, the data, the translations, and our notes from the individual and team discussions constituted the basis for the synthesis. Meta-ethnography is interpretative with its potential to create metaphors for deeper understanding. The interpretative process included awareness and discussions of our pre-understanding. Throughout the process, the team’s constructive and critical dialogues contributed to improving the readings of the data and hence to broaden the understanding. The translations of the findings of each primary study into each other, constantly comparing the translations to generate a new interpretation that subsequently would encompass all the translations into an overarching metaphor. The visual data displays in the translation matrices were helpful, asking questions and going back and forth in the data. A line of argument synthesis (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988) was developed, pulling the translations together, thus, moving beyond the original primary studies. This type of interpretive synthesis, including the use of metaphors, distinguishes meta-ethnography from other review methods. The synthesis should accurately portray both the shared and unique findings of the included studies.

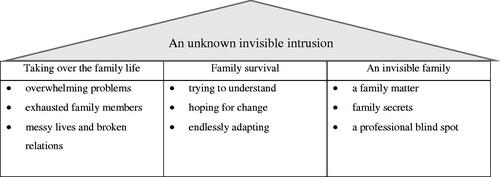

We proceeded from the reciprocal translation, i.e. the findings are directly comparable or analogous, to lines of argument synthesis, where the findings were tied to one another (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). Guided by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988), as well as the new guidelines by France et al. (Citation2019a), we checked the reciprocal translation for possible refutations if the accounts could be set against each other. No such pattern was discerned. The first author presented the metaphors and thematic clustering to all the team members for discussion, and all authors agreed on the final result ().

Expressing the synthesis

The synthesis may be expressed not only by writing a scientific article and presenting a new line of argument synthesis, as we did. It is important to communicate the meta-ethnography to both professional and lay caregivers, as well as to families that encounter PSU. Zhao (Citation1991) describes this as a movement from descriptions of 'what is' to 'what should be'. We recognized this need, and from our theoretical perspective, 'what should be' includes both disciplinary development and new interventions for enhancing family-relational practices.

Results

An unknown invisible intrusion was adopted as an overarching metaphor based on the findings in the 15 studies (). All the included studies described that PSU had an overwhelmingly high cost to families. Both the persons using substances and their family members were pulled into a demanding life situation, with challenges that permeated all aspects of their lives over a long period. By choosing the strong and rough overarching metaphor, we wanted to express the colossal range and severity of the consequences PSU had for all family members and the extent to which these consequences impacted their family dynamics and relations, their everyday life and holidays, and their dreams for the future and stories from the past. The impact was mainly invisible to those on the outside, thus becoming something resembling a family secret. The metaphor An unknown invisible intrusion is accompanied by three main themes: Taking over the family life, Family survival, and An invisible family. To retain the readability of this article, we have chosen to present the occurrence of the themes in the included articles in Appendix VI. The appendix shows that most themes are presented in all included articles.

Taking over the family life

The theme Taking over the family life reflects how overwhelming the problems facing the families were experienced and how exhausted they left them. PSU affected the family structures, and the families experienced messy lives and broken relationships. Three subthemes reflect the families' experiences: Overwhelming problems, Exhausted family members, and Messy lives and broken relations.

Overwhelming problems

The included studies described how ongoing PSU took over family life. The families described how the PSU ruined ordinary family situations. The family member who used drugs or alcohol was described as 'Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde': sometimes they would be the person the families knew, and other times someone who was strongly influenced, hence acting accordingly. The 'Jekyll and Hyde' behavior was experienced as unpredictable by the other family members. They experienced a constant change from stability to crisis and instability.

All included studies described terrifying situations, with numerous episodes of violence and experienced horror. The families tried to manage emerging conflicts and frightening situations by controlling their actions. Some studies described an atmosphere of mistrust and tension, as earlier betrayals made family members constantly suspicious. Fear of relapses or conflicts made it necessary to be in constant preparedness.

Nearly everything in the lives of the families, at emotional, practical, and economic levels, revolved around the family member who was using substances. All the studies described how PSU influenced every important element of everyday family life (e.g. emotional support, trust, feeling safe). It meant that family members lost much of what they experienced as valuable to their families. Their earlier dreams and wishes for life were no longer achievable.

Exhausted family members

As time went by, family members reported that life with PSU had an overwhelmingly high cost. The exhausted family members experienced extreme stress and upsetting situations, and many family members also exhibited various psychosocial and physical symptoms.

The family members' positions in the family (e.g. wife/husband, youngest/oldest child) affected their experiences. Parents, for example, expressed guilt caused by a sense of never-ending responsibility for the adult child. Though, the most vulnerable family members were children as they were the least protected from the consequences of unstable living situations and could not escape from the situations on their own.

Messy lives and broken relations

That PSU affected family structure was described in all the included studies. One individual's problems became the main focus for the whole family, and family functions were organized around and ruled by that focus. Roles in the family changed and became reversed as a result, such as a child becoming the parent's caregiver. Changing roles could lead to suffering for siblings and their families, as the drug-using family member received all their focus.

PSU also led to broken bonds in the families. On the other hand, it could create closer and enmeshed ties between family members. The familial nurturing roles were extended – parents prolonged their involvement in their adult child's life, and adult children took much responsibility for the care of their drug-using or alcohol-using parent. The substance-using family member gave up his or her responsibilities in the family. The option of expelling the drug-using family member from home was a topic that hardly ever came up in these families (Arcidiacono et al., Citation2009; Church et al., Citation2018; Hodges & Copello, Citation2015; McCann et al., Citation2019). This is also conveyed by family members with PSU (Fotopoulou & Parkes, Citation2017). Studies report how family members felt that the drug-using individual also belonged to the family and did not want to leave them homeless (Arcidiacono et al., Citation2009; Church et al., Citation2018; Hodges & Copello, Citation2015). It was also a way of preventing harm to the drug-using family member and controlling the situation.

Family survival

Families who were experiencing An unknown invisible intrusion strived to understand what had happened and how to combat PSU. When they failed, they were endlessly adapting and trying to survive and live as a family. The theme Family survival, concerning how family members tried to adapt to life, has three subthemes: Trying to understand, Hoping for change, and Endlessly adapting.

Trying to understand

PSU had often been a longstanding problem that family members failed to understand. Studies described how family members were aware that something was wrong without recognizing the intrusion's extent and seriousness. When family members discovered the PSU, the initial thought was that the problem could be solved without outside help.

The substance use would often escalate with time, and families would be forced to find a way to relate to it. This could be the start of a long-lasting 'rollercoaster' between hope and mistrust. With time, the families' understanding of the problem would change. The process of change involved re-evaluations of their resources for helping the family member using drugs and often led to a painful process of resignation for the entire family.

Hoping for change

Families wished for the substance-using family member to be different, and they longed for recovery. Studies described many types of inefficient strategies that individual family members or the family collectively, including extremes like ignoring, distancing and using force.

An often-used strategy was trying to control the PSU by limiting access to drugs and alcohol. These attempts were characterized by a lack of consistency since family members struggled to stay firm. The family member who used substances was not the only family member acting unpredictably – the family would also switch between being the helping, supporting, caring Dr. Jekyll and the punishing, angry, controlling Mr. Hyde. 'I tried nicely. I also beat him, just to make him stop drinking, but nothing helped' (Tamutiene & Laslett, Citation2017, p. 429).

Eventually, many families experienced painful resignation upon realizing that nothing could stop the family member from choosing alcohol or drugs over family relations. The family members with PSU who felt that their families tolerated their drug use had often used substances for many years (Fotopoulou & Parkes, Citation2017). The other family members were helplessly watching the self-destruction resulting from PSU. As it was described in one study: 'It is really, really difficult, because you don't… Because it's not your problem' (Moriarty et al., Citation2011, p. 214).

Endlessly adapting

PSU took an overwhelmingly large space in the families' lives. Though they tried to maintain a family life that was as normal as possible, the family member's PSU pushed them into a continuous process of adaptation to an ever-changing intruder. The family members applied what appeared to them to be the best strategy available at any particular moment. Emotionally, PSU was experienced as a family affair. Family members were therefore trying to find family resources as a 'we'. A paradoxical effect of this longstanding family solidarity was to lock family members firmly in demanding situations, like living together despite conflicts, neglecting the needs of siblings or children, or continuing to use time and money to help.

An invisible family

A family experiencing An unknown invisible intrusion were invisible to their social environment and felt loneliness. Cultural, discursive, and strong family values (such as being independent and successful) made PSU a family secret. There was often limited access to help, partially because PSU was difficult for professionals to discover. The theme An invisible family includes three subthemes: A family matter, Family secrets, and A professional blind spot.

A family matter

Across countries and cultures, PSU was to a certain extent perceived as a family matter. However, the experiences were influenced by the cultural context. Cultural notions of the family differ between countries. Attachment to the nuclear and extended family, the so-called 'familism', was especially significant in Mediterranean or Latin families (Arcidiacono et al., Citation2009; Fotopoulou & Parkes, Citation2017). Familism is an ideology that put the family's need prior to the needs of the individuals (Campos et al., Citation2016).

Across the cultures represented in the articles, family members seemed to be concerned about what people outside the family were thinking. Many family members felt shame and blame for being closely related to a person with such difficulties and distanced themselves from social relationships outside the family. Some family members also experienced that the received support from outside 'come at a price' and felt humiliated (Church et al., Citation2018; Fotopoulou & Parkes, Citation2017).

Family secrets

Families described severe loneliness and conflicting needs for privacy and sharing. They described isolation, also inside the family, as a result of it being difficult to speak about their problems. 'It is difficult because it is your family. You fear that it will all go to pieces – although it has already been broken. The situation is hopeless because it is difficult to see any solution to it' (Werner & Malterud, Citation2016, p. 7).

Keeping secrets was also a survival strategy. The families had chosen to silence the problem to retain a positive image of the family. As one of the informants said: 'They did not want to wash the dirty linen in public' (Arcidiacono et al., Citation2009, p. 270). Even children understood that PSU was something they were not supposed to discuss openly.

A professional blind spot

The included studies reported that families faced problems getting help. Family members sought help late in the process and not until they were completely exhausted and/or not managing to cope with the consequences of escalating PSU. Moreover, family members sought help primarily for those who had substance-use difficulties and not for themselves. The substance-using family member could remain a priority even when the family members had to seek help for their own health issues.

When they did seek help, the families often experienced that the help was insufficient or lacking. Family members tried to control the substance-use services their substance-using relative was receiving (e.g. questioned treatment choices, financed private services). Some family members felt responsible for the substance-using family member even in periods of treatment or hospitalization and felt that professionals expected them to do more to help. The included studies also described how the helpers could have unrealistic expectations of the substance-using individual.

Family members experienced a lack of understanding when living with an unknown invisible intrusion. Their situation in complex landscapes of needs for closeness and for distance was not seen or answered by services. The included studies described how families perceived it to be impossible to seek and receive support. The mainstream substance-use services did not have the capacity or resources to offer help to family members. In addition, professionals were not attentive enough to address the problems.

Discussion

The metaphor An unknown invisible intrusion reflects the overwhelming and long-lasting consequences adult family members' PSU had on family life, the struggles families experienced in their attempts to manage the demanding life situation, and the loneliness they were experiencing. The metaphor An unknown invisible intrusion is the overarching theme for this discussion.

The results in this meta-ethnography describe how all-embracing the consequences of adult members' substance use was to themselves and their families. The overwhelming nature of the problems in several areas of family life and the serious short- and long-term consequences for individual family members and the whole family make it problematic to use terms like 'problem' or 'difficulty'. Rather, it seems more apt to view the situation as an intrusion that overshadowed all aspects of life. The studies described families' endless adaptation to an intruder that was constantly changing. Every new strategy brought hope to the families initially, but hope soon turned to despair when it became clear that the strategies for adapting were insufficient. Our findings are in line with Orford et al. (Citation2010), who reviewed the experiences of family members from two decades of qualitative research and found that family members were in a disempowered position as a consequence of the undermining of the control they felt they had over their own lives and the lives of their families (Orford et al., Citation2010).

Our meta-ethnography illuminates several traits associated with PSU that make PSU especially demanding for families. The recovery from substance-use problems is a social process unfolding over time (Dekkers et al., Citation2020; Kougiali et al., Citation2017), and the risk of new episodes of use remains high for a long time. Recovery is also a process with an unknown course because PSU can also be a life-threatening and long-lasting illness. Uncertainty about the outcome is documented to be part of the lives of families dealing with substance-use-related difficulties. In addition, the individual often conceptualizes dependence as an illness or disease (Graham et al., Citation2008). People's close relationships are important for their motivation for treatment, their day-to-day lives, and ongoing recovery (Veseth et al., Citation2019). It is the individual responsible for a decision to stop using substances. Still, the process of recovery has little chance of success if the outside world declines to engage in re-association (Adams, Citation2008). Our results showed how the whole family was influenced when the individual did not decide to change. On the one hand, family members tried to motivate and influence the individual to make the decision. On the other hand, they adapted to the consequences of the decision not being made.

These particular traits of dependence drew all attention to the problem; substance use. Both the persons using substances and the other family members were concerned, and the attention from services was directed at the problem. It seems that this one-sided focus on PSU increased the loneliness and invisibility of these families. A professional blind spot may arise when the focus of the family is to get help to the family member who has the problem rather than to the whole family. Our results showed that the services had the same focus; they also offered services primarily to the individual who had the problem and not the entire family. Several earlier studies (Adams, Citation2008; Copello et al., Citation2010; Selseng & Ulvik, Citation2019) support this finding and have reported how the dominant trends in substance-use policy favor an individual-oriented perspective that provides limited opportunities for integrated work with families.

When the consequences of PSU take the attention, societal conditions can be forgotten. For some substance-using adults, the family's story has been a history of difficult childhood or childhood maltreatment. The Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire (ACE-Q) has provided substantial evidence concerning the link between adverse childhood experiences and adult mental and physical illnesses (Felitti et al., Citation1998; Zarse et al., Citation2019). Familial, social, and individual risk factors increase the possibility of an individual developing a substance use problem (Whitesell et al., Citation2013). Vulnerability for substance use problems seems to be especially heightened among individuals with a family history of substance use disorder (Cservenka, Citation2016). Social problems like poverty, socioeconomic deprivation and unemployment, and familial problems are often present simultaneously.

This study's results clearly showed how involved family members were and how affected family life was. Family life is a complex phenomenon, and what people associate with family life varies. The cultural context has a significant influence on family life, and research carried out in one cultural context cannot be easily transferred to other cultural contexts. Despite the impact of cultural context, families in all the studies seemed to play an important role in supporting and giving practical help to adult members with substance-use problems. Families did not give up easily but remained involved even when their involvement seemed to ruin life as they knew it or wanted it to be. Several dimensions of intergenerational solidarity (see Bengtson & Roberts, Citation1991; Herlofson & Daatland, Citation2016) could be found in the included studies. Studies reported both emotional solidarity, such as closeness and love and functional solidarity, such as practical and financial help. The studies also showed the impact of normative solidarity when duties and obligations were the main arguments for continuing to support the person with PSU.

The studies included in this meta-ethnography presented the experiences of parents, partners and ex-partners, siblings, children, and family members using substances. It is important to keep in mind the different types of relatives occupy different positions in the family when trying to understand the impact of an adult family member's problematic substance use on family life. In most countries, the responsibility for children is mainly attributed to the family (Daatland et al., Citation2009), and parents support their children in transitioning to adulthood long after they reach the age of majority. The results seem to indicate that this transition is complicated, delayed, or missing in families with adult children with substance-use dependence. The familiar tasks and responsibilities usually expected from adult family members were difficult to combine with ongoing substance use. The greater expectations for responsibility associated with the familial role, the harder it was to combine with PSU. The substance-using family member often failed as a grandparent, parent, or partner. As a result, the changed and reversed roles that characterize families with members with PSU have different impacts when the family member is in different stages of family life.

This study illuminates family life with PSU as a process characterized by changing understanding and endless adaptation. This result is in line with other studies suggesting that family members may cope differently with other family members' substance use in different periods of time (Maltman et al., Citation2020). Based on these findings, it is important to shed light on these processes in families. To do so, we need more research on different periods of life with PSU. It is relevant to examine the experiences and understandings of all family members, as well as the family members with PSU, and do so in light of the long-term recovery process. As research indicates that increased family involvement in treatment and long-term recovery can lead to improvements both in PSU patterns and in family functioning (Akram & Copello, Citation2013), interventions that enhance family relational practices need to be investigated.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this meta-ethnography include the rigorous methodology of systematic literature review. It also has the strength and possibilities that qualitative syntheses create for examining participants' meanings, experiences, and perspectives, both deeply and broadly. This meta-ethnography has followed the eMERGe reporting guidance. The use of this guidance improves the transparency and wholeness of the research process, and it is a quality indicator for meta-ethnography. The meta-ethnography team includes both experts in the field that was explored and experts on the methodology.

The systematic search for this meta-ethnography identified over 24,000 studies. With this amount of studies, it is always a possibility that something has been missed or misunderstood. The flexible methodology of meta-ethnography allows us to see this as a strength. With a systematic, peer-reviewed, and extensive search strategy and a large number of articles, we had the opportunity to see different perspectives and ways to describe family life affected by substance use. Regarding the limitations, readers should be mindful of the aim and the search strategy in this meta-ethnography, which were adopted to get a broad understanding of the phenomena. The included studies varied in sample size, represented different countries and described different roles in the families in various stages of life. This ensured rich descriptions of family life and family relationships.

Based on the findings of the current meta-ethnography, further research is essential to address several important knowledge gaps. Despite the well-documented fact that adult family members' PSU affects family life, more nuanced knowledge is needed. In this meta-ethnography, only two studies represented experiences from both substance-using family members and non-using family members (Fotopoulou & Parkes, Citation2017; Näsman & Alexanderson, Citation2017). Based on these two studies, all family members seemed to describe the same influences, but more knowledge is needed to understand nuances and differences. More knowledge is also required from different cultures. This is important to understand the different roles and relations in families and offer these families the help they need. In this study, all different substances were included. We acknowledge that different substances – ranging for instance from opioids with a high risk of overdoses to cannabis, which enjoys acceptance in different subcultures, to alcohol and medicines prescribed by a doctor – may have different implications for family life. It is also important to understand how young persons’ PSU affects family life and relations to parents and siblings, and how this impact may differ from impact of adult family members PSU described in this meta-ethnography. Future research should investigate those distinctive characteristics and nuances in this complex area of knowledge.

Conclusions

The overarching metaphor, an unknown invisible intrusion, reflects the overwhelming consequences adult family members' PSU has on family life, the struggles families experienced in managing a demanding life situation, and their loneliness. We suggest that professionals move from a one-sided focus on PSU to understanding the consequences of long-lasting intrusion into family life. The family members were involved and often wished to stay involved in their substance-using adult family members' lives. They applied what appeared to them to be the best strategies available at any particular moment. The lack of support may suggest that family members were not understood in their complex landscape of needs. Substance use services in many countries still struggle to incorporate family involvement into routine treatment practices. A focus on individual health tends to dominate practices in the field (Selbekk et al., Citation2018). However, the findings suggest that the substance use services need to use strategies that can include individual, household, family, and wider systems. Such interventions already exist, and several systemic family therapeutic approaches are well suited (see Lorås & Ness, Citation2019). ‘The 5-Step Method’ for affected family members is also documented as suited to reduce addiction family-related harm (Copello et al., Citation2010).

We hope that our results contribute to an increased awareness of how involved families often are in the lives of substance-using adults. This awareness may be important to family members experiencing substance use and their social networks, as well as professionals in health and welfare services. These families do not need to be invisible and alone when dealing with an unknown intrusion.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

A special thanks to academic librarians Marianne Nesbjørg Tvedt and Gunhild Austrheim for generously sharing their time and expertise.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1 This study has included family members with PSU.

2 This study has participants with double or triple role. This affects the total number of family members in this meta-ethnography.

3 This study has included participants with PSU.

References

- Adams, P. J. (2008). Fragmented intimacy: Addiction in a social world. Springer Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-72661-8

- Akram, Y., & Copello, A. (2013). Family-based interventions for substance misuse: A systematic review of reviews. Lancet, 382(24), S24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62449-6

- Andersson, C., Best, D., Irving, J., Edwards, M., Banks, J., Mama-Rudd, A., Hamer, R. (2018). Understanding recovery from a family perspective: A survey of life in recovery for families. Project Report. Sheffield Hallam University for Alcohol Research UK. Retrieved from http://shura.shu.ac.uk/id/eprint/18890

- Arcidiacono, C., Velleman, R., Procentese, F., Albanesi, C., & Sommantico, M. (2009). Impact and coping in Italian families of drug and alcohol users. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 6(4), 260–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802182263

- Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 11–59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

- Bengtson, V. L., & Roberts, R. E. (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.2307/352993

- Bondas, T., & Hall, E. (2007a). A decade of metasynthesis research: A meta-method study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 2(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620701251684

- Bondas, T., & Hall, E. (2007b). Challenges in the approaches to metasynthesis research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306295879

- Campos, B., Perez, O. F. R., & Guardino, C. (2016). Familism: A cultural value with implications for romantic relationships in U.S. Latinos. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514562564

- Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (1989). The expanded family life cycle: A framework for family therapy. Allyn & Bacon.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Alcohol Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ARDI

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Church, S., Bhatia, U., Velleman, R., Velleman, G., Orford, J., Rane, A., & Nadkarni, A. (2018). Coping strategies and support structures of addiction affected families: A qualitative study from Goa, India. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 36(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000339

- Copello, A., Templeton, L., & Powell, J. (2010). The impact of addiction on the family: Estimates of prevalence and costs. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 17 (Suppl 1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2010.514798

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Cservenka, A. (2016). Neurobiological phenotypes associated with a family history of alcoholism. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 158, 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.021

- Daatland, S. O., Veenstra, M., & Lima, I. A. (2009). Helse, familie og omsorg over livsløpet. NOVA Rapport, 4/09. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7577/nova/rapporter/2009/4

- Dekkers, A., De Ruysscher, C., & Vanderplasschen, W. (2020). Perspectives on addiction recovery: Focus groups with individuals in recovery and family members. Addiction Research & Theory, 28, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2020.1714037

- dos Reis, L. M., Aparecida Sales, C., & de Oliveira, M. L. F. (2017). Narrative of a drug user's daughter: Impact on family daily routine. Anna Nery School Journal of Nursing/Escola Anna Nery Revista de Enfermagem, 21(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2017-0080

- Doyle, L. H. (2003). Synthesis through meta-ethnography: Paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033003

- Edwards, M., Best, D., Irving, J., & Andersson, C. (2018). Life in recovery: A families' perspective. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 36(4), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2018.1488553

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Fereidouni, Z., Joolaee, S., Fatemi, N. S., Mirlashari, J., Meshkibaf, M. H., & Orford, J. (2015). What is it like to be the wife of an addicted man in Iran? A qualitative study. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2014.943199

- Fleury, M. J., Djouini, A., Huýnh, C., Tremblay, J., Ferland, F., Ménard, J. M., & Belleville, G. (2016). Remission from substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 168, 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.625

- Fotopoulou, M., & Parkes, T. (2017). Family solidarity in the face of stress: Responses to drug use problems in Greece. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(4), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1279152

- France, E. F., Cunningham, M., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Maxwell, M., Roberts, R. J., Turley, R. L., Booth, A., Britten, N., Flemming, K., Gallagher, I., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Lewin, S., Noblit, G. W., Pope, C., Thomas, J., … Noyes, J. (2019a). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

- France, E. F., Uny, I., Ring, N., Turley, R. L., Maxwell, M., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Roberts, R. J., & Noyes, J. (2019b). A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7

- Graham, M. D., Young, R. A., Valach, L., & Alan Wood, R. (2008). Addiction as a complex social process: An action theoretical perspective. Addiction Research & Theory, 16(2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350701794543

- Herlofson, K., & Daatland, S. O. (2016). Forskning om familiegenerasjoner. En kunnskapsstatus. Norsk institutt for forskning og oppvekst, velferd og aldring. NOVA Rapport. 2016. Consumption, Harm and Policy Responses in 30 European Countries 2019, 2. https://doi.org/10.7577/nova/rapporter/2016/2

- Hodges, M., & Copello, A. (2015). How do I tell my children about what my mum's like?' Conflict and dilemma in experiences of adult family members caring for a problem-drinking parent. Families, Relationships and Societies, 4(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674314X13951456077308

- Kougiali, Z., Fasulo, A., Needs, A., & Van Laar, D. (2017). Planting the seeds of change: Directionality in the narrative construction of recovery from addiction. Psychology & Health, 32(6), 639–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1293053

- Lorås, L., & Ness, O. (2019). Håndbok i familieterapi [Handbook of family therapy]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Maltman, K., Savic, M., Manning, V., Dilkes-Frayne, E., Carter, A., & Lubman, D. (2020). Holding on' and 'letting go': A thematic analysis of Australian parent's styles of coping with their adult child's methamphetamine use. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2019.1655547

- McCann, T. V., Polacsek, M., & Lubman, D. I. (2019). Experiences of family members supporting a relative with substance use problems: A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(4), 902–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12688

- McKay, J. (2017). Making the hard work of recovery more attractive for those with substance use disorders. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 112(5), 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13502

- McLellan, A. T., Lewis, D. C., O'brien, C. P., & Kleber, H. D. (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA, 284(13), 1689–1695. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.13.1689

- Moriarty, H., Stubbe, M., Bradford, S., Tapper, S., & Lim, B. T. (2011). Exploring resilience in families living with addiction. Journal of Primary Health Care, 3(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1071/hc11210

- Näsman, E., & Alexanderson, K. (2017). Parents with substance abuse problems – Meetings between children and the parents’ perspective. [Föräldrar med missbruksproblem: möten mellan barns och föräldrars perspektiv. ]. Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift, 94(4), 447–456.

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). SAGE.

- Ólafsdóttir, J., Orjasniemi, T., & Hrafnsdóttir, S. (2020). Psychosocial distress, physical illness, and social behaviour of close relatives to people with substance use disorders. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 20(2), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2020.1749363

- Orford, J., Velleman, R., Copello, A., Templeton, L., & Ibanga, A. (2010). The experiences of affected family members: A summary of two decades of qualitative research. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 17(Suppl 1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2010.514192

- Orr, L. C., Barbour, R. S., & Elliott, L. (2014). Involving families and carers in drug services: Are families' part of the problem? Families, Relationships and Societies, 3(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674313X669900

- Ray, G., Mertens, J., & Weisner, C. (2007). The excess medical cost and health problems of family members of persons diagnosed with alcohol or drug problems. Medical Care, 45(2), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000241109.55054.04

- Rodriguez, L. M., Neighbors, C., & Knee, C. R. (2014). Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(4), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2013.841890

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer.

- Selbekk, A. S. (2019). A window of opportunity for children growing up with parental substance-use problems. Nordisk Alkohol & Narkotikatidskrift, 36(3), 205–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072519847013

- Selbekk, A. S., Adams, P. J., & Sagvaag, H. (2018). “A Problem Like This Is Not Owned by an Individual": Affected family members negotiating positions in alcohol and other drug treatment. Contemporary Drug Problems, 45(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918773097

- Selseng, L. B., & Ulvik, O. S. (2019). Rusproblem og endring i eit diskursperspektiv: Ein analyse av praksisforteljingar. Norsk Sosiologisk Tidsskrift, 3(06), 442–456. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-2512-2019-06-05

- Sheedy, C. K., & Whitter, M. (2013). Guiding principles and elements of recovery-oriented systems of care: What do we know from the research? Journal of Drug Addiction, Education, and Eradication, 9(4), 225.

- Tamutienė, I., & Jogaitė, B. (2019). Disclosure of alcohol-related harm: Children's experiences. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 36(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072518807789

- Tamutiene, I., & Laslett, A. M. (2017). Associative stigma and other harms in a sample of families of heavy drinkers in Lithuania. Journal of Substance Use, 22(4), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2016.1232760

- Tinnfalt, A., Froding, K., Larsson, M., & Dalal, K. (2018). ‘I feel it in my heart when my parents fight': Experiences of 7-9-year-old children of alcoholics. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(5), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0544-6

- Vedeler, G. H. (2011). Familien som ressurs i psykososialt arbeid, del I. Fokus på Familien, 39(04), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN0807-7487-2011-04-03

- Veseth, M., Moltu, C., Svendsen, T. S., Nesvåg, S., Slyngstad, T. E., Skaalevik, A. W., & Bjornestad, J. (2019). A stabilizing and destabilizing social world: Close relationships and recovery processes in SUD. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 6(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-019-00137-9

- Weimand, B. M., Birkeland, B., Ruud, T., & Høie, M. M. (2020). ‘It’s like being stuck on an unsafe and unpredictable rollercoaster’: Experiencing substance use problems in a partner. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 37(3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520904652

- Werner, A., & Malterud, K. (2016). Children of parents with alcohol problems performing normality: A qualitative interview study about unmet needs for professional support. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30673. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30673

- White, W. L., & Kelly, J. F. (2011). Alcohol/drug/substance ‘abuse’: The history and (hopeful) demise of a pernicious label. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(3), 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2011.587731

- Whitesell, M., Bachand, A., Peel, J., & Brown, M. (2013). Familial, social, and individual factors contributing to risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Addiction, 2013, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/579310

- WHO. (1996). Multiaxial classification of child and adolescent psychiatric disorderes. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders in children and adolescents. Cambridge University Press.

- WHO. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/alcohol#tab=tab_1

- World Drug Report. (2019). (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.19.XI.8). https://wdr.unodc.org/wdr2019/

- Zarse, E. M., Neff, M. R., Yoder, R., Hulvershorn, L., Chambers, J. E., & Chambers, R. A. (2019). The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine, 6(1), 1581447. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2019.1581447

- Zhao, S. (1991). Metatheory, metamethod, meta-data-analysis: What, why, and how? Sociological Perspectives, 34(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389517