Abstract

This article analyzes the riskiness attached to illicit drug use by means of a social representations framework. The implications of these social representations are further studied through their associations with views on drug policy: restrictive control and harm reduction measures. The data for the study is from a Finnish Drug Survey (N = 3229). Latent class analysis (LCA) and multinomial logistic regression analysis were used to analyze the data. Four representational profiles of perceived risk were identified: high-risk (70% of respondents), cannabis OK (15%), experimenting OK (10%), and low-risk (2%). All illicit drug use was considered as a moderate or high risk in the high-risk profile. Cannabis was considered less risky than other substances in the cannabis OK profile and experimenting was a less risky way of use in the experimenting OK profile. Most people in the low-risk profile considered the risks related to illicit drug use as nonexistent or minor. These representational profiles were also connected to opinions on drug policy: those who saw the most risks with use tended to support restrictive control measures, while those who considered illicit drug use to be less risky were more accepting toward harm reduction measures.

The social representations theory (Moscovici, Citation1973, Citation1988) offers a useful way to focus on lay people’s understandings of a socially contested issue, such as illicit drug use. Social representations originate from the shared knowledge within groups rather than from the private knowledge of individuals (Herzlich & Pierret, Citation1989; Joffé, Citation2003), and different groups may hold different social representations on the same issue (Moscovici, Citation1973, Citation1988; Liu & Sibley, Citation2013). Because social representations are inherently political and people approve of or challenge existing social relations and policies through them (Staerklé, Citation2009), in this article we analyze the connections between social representations of illicit drug use and views on drug policy.

Risk is readily associated with the social representations of illicit drug use, which is traditionally viewed as deviant and harmful behavior, subject to stigmatization and moral judgment. These views are being challenged as substances and the ways of using them become more varied (World Drug Report, Citation2019). One example of the contemporary attitudinal atmosphere could be described through differentiated normalization. According to this approach, some substances and ways of illicit drug use have become commonplace and accepted by the mainstream while others remain stigmatized and rejected (e.g. MacDonald & Marsh, Citation2002; Shildrick, Citation2002; Williams, Citation2016). Normification, on the other hand, refers to the idea that although illicit drug use is still largely stigmatized, the issue has become a salient and permanent part of modern societies (Goffman, Citation1963; Hathaway et al., Citation2011). In line with these ideas, we argue that current views on the riskiness of illicit drug use are diverse rather than homogeneous and further, that they have implications in terms of people’s views on drug policy.

To study this, we use a population-based Drug Survey conducted in Finland in 2018 as research data. The survey aims to collect information on and monitor the changes in Finnish people’s drug use and their opinions and attitudes towards the use of illicit drugs. While often the aim of qualitative analyses, the benefit of a quantitative approach in the study of social representations has been highlighted by Liu and Sibley (Citation2013), for example, who state that social representations are complex social phenomena that need to be studied in various ways to be properly assessed. Following their argument, the statistical analyses used in this study offer a way of operationalizing the extent of the social representations of illicit drug use shared across society (Liu & Sibley, Citation2013).

A focus on drug policy is very current, as a zero-tolerance approach to illicit drug use is unrealistic in industrialized societies, forcing policies to be actively re-evaluated and modified—in Finland as well as globally. This leads to balancing two main drug policy approaches: restrictive control and harm reduction. In Finland, the application of restrictive control and harm reduction measures has led to a dual-track policy: on the one hand, control is very tight in that all drug-related activity (including drug use) is criminalized. On the other hand, there is a strong focus on harm reduction, and services have been successfully developed and employed since the initiation of the first needle and syringe exchange in 1997. (Tammi, Citation2005; Hakkarainen et al., Citation2007) These two tracks create the general landscape followed by the population’s views on drug policy. As an indication of increased drug political activism, a citizens’ initiative calling for the decriminalization of cannabis use, possession of a small amount, and growing of four cannabis plants for personal use received 59,609 certified signatures and then qualified for the Parliament proceedings in 2020 (KAA 5/2020 vp). Another current drug policy discussion in Finland is the establishment of a consumption room in Helsinki, which has thus far been supported mainly by individual politicians, experts, and practitioners rather than by institutions and organizations (Unlu et al., Citation2021).

In a time of drug policy reforms, it is important to understand the reasons behind the public support of specific policies. The effect of public opinion on policy is not straightforward, but the former certainly set important parameters for the latter (Manza & Cook, Citation2002). In regards to drug policy, lay views and opinions on it have been studied for example related to drug testing at work (e.g. Fendrich & Kim, Citation2002), in sports (e.g. Dunn et al., Citation2010) or at school (e.g. Garland et al., Citation2012) or initiating new harm reduction measures such as consumption rooms (e.g. Small et al., Citation2006; Hayle, Citation2015; Jauffret-Roustide & Cailbault, Citation2018). Studies on consumption rooms suggested, for example, that how the public felt about this issue, the ‘public mood’, affected policy change when it was aligned with the detection of the drug problem and an open policy window (Hayle, Citation2015). The initiation of consumption rooms has also been attributed to indicating the relevance of multiple actors – including residents of an area and people who use illicit drugs (Jauffret-Roustide & Cailbault, Citation2018) – and a wider cultural change among the people of society (Small et al., Citation2006). Support for political change also requires a change in the social representations that maintain these practices.

As far as we know, the social representations theory (SRT) has not been largely applied to the field of illicit drug use, although some research exists focusing on the images of addiction (Blomqvist, Citation2009; Hirschovits-Gerz, Citation2013), categories of drug users (Echabe et al., Citation1992) or the construction of social representations of drugs on a more theoretical level (Negura & Plante, Citation2021). For the study at hand, we use the SRT to conceptualize lay knowledge of illicit drug use as more than individual attitudes or opinions. Firstly, the analysis contributes to efforts to make sense of the riskiness related to illicit drug use in terms of varying social representational profiles shared within different groups of people. Secondly, we analyze how the social representations of the riskiness of illicit drug use are related to opinions on drug policy.

Social representations of risk and their political implications

Social representations are collections of values, ideas, images, and practices shared within a culture or group. Their main purpose is to help people orient and communicate in their social and material worlds (Moscovici, Citation1973, Citation1988) and to take a stand regarding the existing social order (Staerklé, Citation2009). There is a long tradition of research on the social representations of risk about health and safety hazards, such as AIDS (Marková & Wilkie, Citation1987; Herzlich & Pierret, Citation1989; Joffé, Citation2003), mental illness (Jodelet, Citation1991), and genetically modified foods (Bäckström et al., Citation2003). For the requirements of this study, the definition of risk as the probability of a negative outcome is sufficient (Joffé, Citation1999, p. 4). Understood in this broad sense, the risks connected to illicit drug use can include diverse health or social consequences, either to the users or to their immediate or wider environment.

According to SRT, risks are constructed through the experiences and knowledge of in-groups and by drawing on the cultural environment and its historical analogies and symbols (Joffé, Citation2003; Joffé & Lee, Citation2004). The emphasis is not on whether perceptions of risk are ‘correct’, but on the commonsense knowledge that these perceptions generate (Bauer & Gaskell, Citation1999; Joffé, Citation2003). Perception of risk is a key factor in the initiation of drug use (Bejarano et al., Citation2011) and in how one sees other people who use illicit drugs (Musher-Eizenman et al., Citation2003). In a previous study examining namely the risk attributed to the use of illicit drugs, people were found to associate the biggest risk to becoming addicted to hard drugs (heroin, cocaine, amphetamines), which were also regarded as the biggest risks for the society (Blomqvist, Citation2009).

Politically, social representations are closely linked to power; they create social reality and meaning (Sakki et al., Citation2017) and organize social and political practices (Staerklé, Citation2009, Citation2011; Elcheroth et al., Citation2011). For this reason, we analyze how the social representations of riskiness related to illicit drug use are connected to opinions on drug policy. The political thinking of lay people is embedded in specific contexts and originates from shared experiences and values. It is often based on stereotypical images of groups and works as a means of regulating the relationship between different groups in society (Staerklé, Citation2009). As specific experiences and values that build social representations are shared to different extents by individuals (Doise et al., Citation1999), we can expect the riskiness of illicit drug use to be viewed differently among Finnish people. We explore this diversity of views specifically as representational profiles found in general population data. After discovering an emerging group structure, we analyze the association of these representational profiles with views on drug control and harm reduction policy measures.

Data and methods

In this article, we apply a quantitative approach to the study of social representations (see, e.g. Liu & Sibley, Citation2013; Sibley & Liu, Citation2013). Our data is from a Finnish population-based Drug Survey administered by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. The survey gathers information on illicit drug use and the views and attitudes of Finnish people about drug use more generally. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare.

Data were collected by Statistics Finland via a self-administered anonymous online/postal questionnaire. The survey sample was a representative random sample (N = 7000) of Finnish people aged 15 to 69 drawn from the Finnish Population Information System. Institutionalized members of the population, people without a permanent address, and people living on the Åland Islands were excluded. Younger age groups (15–39) were oversampled to increase analytical power in the age group that uses drugs most actively. To restore the population representation in terms of age, gender, education, and the level of urbanization, weighting coefficients were calculated by Statistics Finland. The Drug Survey data has been collected every four years since 1992 and the study protocol is described more thoroughly elsewhere (Finnish Social Sciences Data Archive, Citation2014; Karjalainen et al., Citation2020). The data for this study is from the latest survey in 2018, with 3,229 respondents and a response rate of 46 percent.

Measurements

To analyze the perceived risk related to illicit drugs, we used the questions ‘How high is the (health or other) risk of doing the following?’: (a) trying cannabis once or twice, (b) using cannabis regularly, (c) trying ecstasy once or twice, (d) using ecstasy regularly, (e) trying amphetamine once or twice, (f) using amphetamine regularly, (g) trying heroin once or twice, and (h) using heroin regularly (1 = no risk, 2 = low risk, 3 = moderate risk, 4 = high risk). These questions have been adopted and applied for the Drug Survey from the European Model Questionnaire (EMCDDA – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs & Drug Addiction, Citation2002a). We chose to include the questions on cannabis, ecstasy, amphetamine, and heroin as they are the most widely used and/or recognized illicit drugs in Finland (Karjalainen et al., Citation2020). The variables were recoded as dichotomous (1 = no or low risk, 2 = moderate or high risk).

Views on drug policy were analyzed by questions on control and harm reduction measures. For control, we used a question on punishment: ‘Should a person be punished for illicit drug use?’ (1 = should not be punished, 2 = yes, with a fine, 3 = yes, with a prison sentence, 4 = yes, in another way). Another question also served as a measure of control: ‘What is your opinion on drug testing at work?’ (1 = I find it completely acceptable, 2 = I find it somewhat acceptable, 3 = I do not accept it, 4 = I object to it, 5 = I cannot say).

To analyze opinions on harm reduction measures, we used the questions ‘What is your opinion on the following measures or services: (a) a needle and syringe exchange, (b) consumption rooms?’ (1 = I find it completely acceptable, 2 = I find it somewhat acceptable, 3 = I do not accept it, 4 = I object to it, 5 = I cannot say). These specific questions were chosen to represent an established harm reduction service (needle and syringe exchange) and a new harm reduction service currently under discussion (consumption rooms). The responses for drug testing at work and harm reduction measures were recoded into three categories: 1 = accept, 2 = do not accept or object, 3 = cannot say.

The background variables used in the analyses were gender (male, female), age (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–69), level of education (primary, secondary, tertiary), residential area (urban, semi-urban, rural) and personal history of illicit drug use (whether the respondent had tried or used an illicit drug during their lifetime, yes/no).

Analyses

First, we classified the data into representational profiles based on perceptions of risk related to illicit drug use. This was done through latent class analysis (LCA) using Latent Gold 5.0 software (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2013). LCA is a non-parametric finite mixture model that allowed us to identify different categories of people with distinct representational profiles underlying the variation in item responses. It is similar to cluster analysis but does not assume different groups a priori, and it measures both class-membership probabilities and item-response probabilities. The appropriate number of classes is chosen based on the parsimony and interpretability of the results (Porcu & Giambona, Citation2017). The analysis yields several fit indices to help determine the model with the most appropriate amount of classes. The most commonly used indices are information criteria, such as the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC), consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC) (Nylund et al., Citation2007; Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018), and Approximate Weight of Evidence (AWE) (Masyn, Citation2013; Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018), in which lower values indicate better model fit. Out of these information criteria, the BIC has been found to outperform the others in data sets of different sizes (Nylund et al., Citation2007). We analyzed models ranging from one to five latent classes and focused on the BIC in model selection.

Second, we used multivariable multinomial logistic regression to analyze the associations between the representational profiles and views on drug policy. We chose multinomial logistic regression as the method of analysis because the dependent variables were nominal on more than two levels. Views on control measures were first considered by comparing those who supported punishment by fines, prison, or other with those who did not support punishment (). Next, another measure of control measure, drug testing at work, was analyzed by comparing those who did not accept testing and those who could not say with those who did accept testing (). The same was done for harm reduction measures, namely, needle exchange and consumption rooms (). These multivariable multinomial logistic regression models were adjusted for the background variables of gender, age, level of education, residential area, and personal history of illicit drug use. SPSS 25 was used to analyze the data, and weighting coefficients were used in all the analyses. The results for these analyses are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and their 95 percent confidence intervals (CI).

Table 1. Views on punishment for illicit drug use among the Finnish general population, N = 3229, multivariable multinomial logistic regression.

Table 2. Opinions on drug testing at work among the Finnish general population, N = 3229, multivariable multinomial logistic regression.

Table 3. Opinions on needle exchange and consumption rooms among the Finnish general population, N = 3229, multivariable multinomial logistic regression.

Results

Representational profiles of perceived risk

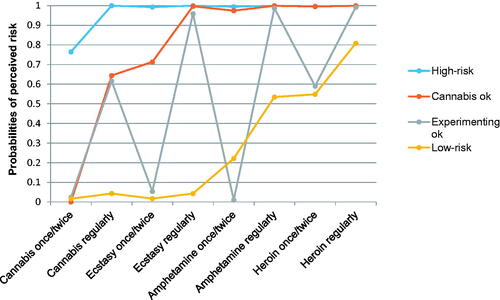

shows the different models with between one and five classes that were estimated through latent class analysis. The BIC, CAIC, and AWE were lowest in the four-class model, while the SABIC favored the five-class solution. Due to the strongest evidence for the BIC as the most appropriate model (e.g. Nylund et al., Citation2007) and the reasonable interpretability of the classes, the four-class model was chosen. below shows the item-response probabilities for the four-class model. We named and interpreted the four representational profiles as follows:

Table 4. Model fit indices for models with one to five classes.

Profile 1: High-risk

The first profile consists of approximately 70 percent of respondents, who have a high probability of viewing all illicit drug use as a moderate or high risk. High probabilities apply to all substances, as well as to both trying the substance once or twice and using it regularly.

Profile 2: Cannabis OK

Although the respondents in the second profile are also likely to view illicit drug use as risky, they see cannabis as an exception. The probability of seeing experimenting with cannabis once or twice as a moderate or high risk is near zero. The regular use of cannabis is also less likely to be viewed as a moderate or high risk than in the first profile. Fifteen percent of the respondents belong to this profile.

Profile 3: Experimenting OK

The third profile includes 10 percent of the respondents and follows a response pattern according to which trying any illicit drug once or twice is unlikely to be viewed as risky, but regular use of the drug is likely to be viewed as a moderate or high risk.

Profile 4: Low-risk

About two percent of the respondents are categorized as having a low probability of viewing any illicit drug use as a moderate or high risk. This applies especially to the use of cannabis and ecstasy, as the probabilities of perceiving risk are higher with harder substances.

shows the distributions of the demographic variables (gender, age, level of education, residential area), the respondents’ personal history of illicit drug use and their views on drug policy measures in each of the four representational profiles identified through LCA.

Table 5. The distribution of relevant variables within the representational profiles.

Views on drug policies

The four representational profiles were used as an independent variable in multivariable multinomial logistic regression models to study views on drug policy. First, drug policy control measures are shown in and . shows whether and, if so, how people in the profiles think illicit drug use should be punished. Those in the high-risk and cannabis OK profiles were more likely than those in the low-risk profile to support all kinds of punishments for illicit drug use. For example, the odds for supporting prison as the means of punishment were notably higher among those in the high-risk profile (aOR 21.8) and those in the cannabis OK profile (aOR 3.6), compared to those in the low-risk profile. There were no statistically significant differences in the views of those in the experimenting OK and low-risk profiles. People living in an urban area were more likely to be against punishment for illicit drug use than people living in rural areas. Drug testing at work () was more likely to be accepted by those in the high-risk and cannabis OK profiles, while those in the low-risk profile were more likely to not accept them and to answer ‘cannot say’.

Second, the acceptance of harm reduction measures is shown in . There were no statistically significant differences in the acceptance of needle and syringe exchange between those in the high-risk, cannabis OK, and experimenting OK profiles compared to those in the low-risk profile (5a). About consumption rooms, however, those in the high-risk profile were less likely to accept them (5b). Education was significantly associated with opinions on harm reduction: those with a primary or secondary level of education were less likely to accept these services than those with a tertiary level of education. As with views on control measures, one’s personal history of illicit drug use was significant: those who had tried or used illicit drugs during their lifetime were more likely to accept harm reduction measures.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the riskiness related to illicit drug use as collectively shared knowledge. This social representations approach allowed us to analyze the phenomenon as more than individual attitudes: as positions taken toward illicit drug use that are also related to opinions on drug policy measures. By using the method of latent class analysis to study social representations, we were able to discover the emerging group structure and statistically significant differences in riskiness associated with illicit drug use as four categorically distinct representational profiles: high-risk, cannabis OK, experimenting OK, and low-risk. The risk was attributed to substances and amounts of use differently in the four profiles, showing that the social representations of risk associated with illicit drug use are not homogenous. A vast majority of people considered all illicit drug use to be risky, although some distinguished between substances, mainly judging cannabis to be less risky than others. Distinctions were also made between different modes of use: using illicit drugs regularly was considered risky more widely than trying them once or twice. The study adds to the scant literature of social representations in the field of illicit drug use and to showing the relevance of these social representations in understanding views on policy.

That is to say, risk perceptions were related to views on drug policy: Those in the high-risk and cannabis OK profiles were more likely to support punishments for illicit drug use than those in the low-risk profile. Drug testing at work as a control measure was also more likely to be accepted by those in the high-risk and cannabis OK profiles. Opinions on harm reduction measures varied. Regarding the acceptability of needle and syringe exchange, there were no differences between those in the high-risk, cannabis OK and experimenting OK profiles, compared to those in the low-risk profile. This result implies that the service is well established in society and widely accepted by people. Consumption rooms, however, are currently only under public debate in Finland, and they were less likely to be accepted by those in the high-risk profile. The results on harm reduction resemble findings from previous research, which found consumption rooms, for example, to be more likely supported by people who did not think that illicit drug users should be treated as criminals but rather using social and health assistance (e.g. Cruz et al., Citation2007). In regards to background variables, education was associated with more support for harm reduction measures (also Cruz et al., Citation2007), and respondents’ drug use was significantly related to views on drug policy. Personal drug use has also previously been connected with less support for punitive policy measures (Garland et al., Citation2012) and more sympathetic attitudes towards therapeutic interventions (Cruz et al., Citation2007)

We briefly mentioned the differentiated normalization of illicit drug use at the beginning of this article, and we now turn back to it in interpreting our results. Our findings show that different groups of people have varying social representations related to the riskiness of illicit drug use: not all forms of drug use are perceived as equally detrimental or delinquent. Based on the analyses, we can say that using cannabis or trying other drugs once or twice are forms of illicit drug use that are more accepted and perhaps more normalized. This has also been shown by other studies: cannabis is more accepted than other drugs (e.g. Parker et al., Citation2002) and recreational use is more accepted than other kinds of use (e.g. Duff, Citation2005). Although our results support the perception of cannabis as an illicit drug that is different from others, the vast majority of Finnish people still consider trying or using any illicit drug, cannabis included, as risky behavior that should be punishable by law. Differentiated normalization based on several co-occurring social representations, nevertheless, leads to a shift in the general attitudinal atmosphere about drug use issues and, possibly together with an open policy window, can lead to challenging and changing drug policy measures and practices (see also Small et al., Citation2006; Hayle, Citation2015; Jauffret-Roustide & Cailbault, Citation2018). In Finland, this is currently exemplified through discussions on establishing consumption rooms and the citizen’s initiative to decriminalize the use of cannabis. The latter might also in part be attributable to changes in cannabis policies in several other countries (e.g. EMCDDA – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs & Drug Addiction, Citation2020b).

Even more accurately than through differentiated normalization, we explain our results through the concept of normification, introduced by Goffman (Citation1963) and applied to the substance use field also by Hathaway et al. (Citation2011). Whereas by definition, normalization means that something has become so normal that it is no longer stigmatized, normification does not imply that illicit drug use is labeled non-deviant but that it has become a salient and permanent part of modern societies. Similar drugs and similar drug-using behaviors among different social groups (class, race, and gender) are differently accommodated and accepted by the mainstream (O’Gorman, Citation2016), which leaves room for the stigmatization of people who deviate from whatever one regards as acceptable. Our study suggests that even though respondents might (or might not) think of illicit drug use as a permanent part of their society, it is not normalized to the point of being insignificant or not stigmatized. Rather, the strong support for punishment, for example, indicates a moralistic evaluation of drug use as an issue that should be dealt with through the criminal control system.

Harsh punishments and restrictive control were supported by people who considered illicit drug use to be highly risky; Staerklé (Citation2009, Citation2013) refers to the concepts of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ citizen in his studies on lay people’s policy attitudes, and he notes that people with traditional and authoritarian values tend to make such a categorization. These people also support punishing ‘bad’ citizens through repressive policies. Only fifteen percent of people in the high-risk profile in the current study had tried or used an illicit drug during their lifetime. Therefore, we suggest that they may be making a clearer distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ — that is, between the ‘good’ citizens who have not used illicit drugs and the ‘bad’ citizens who have. Support for a restrictive policy still stems from the perception of illicit drug use as something deviant, being the behavior of people who are different from oneself. Those who have tried illicit drugs, be it only once or twice, may see more diversity in using without coming to significant harm. The policy offers one way of regulating the relationships between threatening and conforming groups at the institutional level (Staerklé, Citation2013).

Limitations

The survey data used for the study presents some limitations. Due to the sampling protocol, members of the institutionalized population and those without a permanent address were excluded; therefore, for example, people who use drugs problematically may remain underrepresented. The survey questions also set limits on the research and results. The question on risk is coarse, and we cannot know what sorts of risks respondents are thinking of when answering the question. Whatever risks the respondents consider, however, contribute to their understandings of illicit drug use as something perhaps undesirable in their environment. These understandings, then, have further relevance in regards to their views on drug policy. The questions on drug policy in the questionnaire are also limited and only provide some examples of different measures. We chose the questions on punishment, drug testing at work, needle exchange and consumption rooms to try to capture a sample of different measures of both restrictive control and harm reduction. The conclusions made based on these concrete questions are limited to providing a look into views concerning current drug policy measures rather than larger sets of values behind the support of specific kinds of drug policy. In regards to the respondent’s drug use, it should be noted that we used a coarse measure of drug use in a lifetime, which can include different patterns of use as substances or frequency of use was not specified. The response rate of the Drug Survey in 2018 was somewhat lower than during previous data collections, but 46 percent matched the anticipated share, as response rates have been declining in surveys overall.

Conclusion

This study shows that the social representations of risk related to illicit drug use are diverse, although the majority of people view illicit drug use as risky behavior. These representations are associated with opinions on drug policy: restrictive criminal control is supported by those who consider the risks of illicit drug use to be high, while those who consider risks to be lower tend to be in favor of harm reduction measures. If one acknowledges this diversity, one is better equipped to understand illicit drug use as a normified contemporary phenomenon, as well as some of the reasons behind political lay thinking and political change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bäckström, A., Pirttilä-Backman, A. M., & Tuorila, H. (2003). Dimensions of novelty: A social representation approach to new foods. Appetite, 40(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00005-9

- Bauer, M. W., & Gaskell, G. (1999). Towards a paradigm for research on social representations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 29(2), 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00096

- Bejarano, B., Ahumada, G., Sánchez, G., Cadenas, N., de Marco, M., Hynes, M., & Cumsille, F. (2011). Perception of risk and drug use: An exploratory analysis of explanatory factors in six Latin American countries. The Journal of International Drug, Alcohol and Tobacco Research, 1(1), 9–17.

- Blomqvist, J. (2009). What is the worst thing you could get hooked on?: Popular images of addiction problems in contemporary Sweden. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 26(4), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600404

- Cruz, M. F., Patra, J., Fischer, B., Rehm, J., & Kalousek, K. (2007). Public opinion towards supervised injection facilities and heroin-assisted treatment in Ontario. International Journal of Drug Policy, 18(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.001

- Doise, W., Spini, D., & Clémence, A. (1999). Human rights studied as social representations in a cross-national context. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199902)29:1<1::AID-EJSP909>3.0.CO;2-#

- Duff, C. (2005). Party drugs and party people: Examining the ‘normalization’ of recreational drug use in Melbourne, Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16(3), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.02.001

- Dunn, M., Thomas, J. O., Swift, W., Burns, L., & Mattick, R. P. (2010). Drug testing in sport: The attitudes and experiences of elite athletes. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 21(4), 330–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.12.005

- Echabe, A. E., Guede, E. F., Guillen, C. S., & Garate, J. F. V. (1992). Social representations of drugs, causal judgment and social perception. European Journal of Social Psychology, 22(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420220108

- Elcheroth, G., Doise, W., & Reicher, S. (2011). On the knowledge of politics and the politics of knowledge: How a social representations approach helps us rethink the subject of political psychology. Political Psychology, 32(5), 729–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00834.x

- EMCDDA – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2002a). Handbook for surveys on drug use among the general population. EMCDDA project CT.99.EP.08 B, EMCDDA.

- EMCDDA – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2020b). Monitoring and evaluating changes in cannabis policies: insights from the Americas. Technical report, EMCDDA.

- Fendrich, M., & Kim, J. Y. S. (2002). The experience and acceptability of drug testing: Poll trends. Journal of Drug Issues, 32(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260203200104

- Finnish Social Sciences Data Archive. (2014). FSD3181 Alcohol and Drug Survey 2014. https://services.fsd.tuni.fi/catalogue/FSD3181?tab=summary&study_language=en&lang=en

- Garland, T. S., Bumphus, V. W., & Knox, S. A. (2012). Exploring general and specific attitudes toward drug policies among college students. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 23(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403410389807

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Pretice-Hall.

- Hakkarainen, P., Tigerstedt, C., & Tammi, T. (2007). Dual-track drug policy: Normalization of the drug problem in Finland. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 14(6), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630701392008

- Hathaway, A. D., Comeau, N. C., & Erickson, P. G. (2011). Cannabis normalization and stigma: Contemporary practices of moral regulation. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 11(5), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895811415345

- Hayle, S. (2015). Comparing drug policy windows internationally: Drug consumption room policy making in Canada and England and Wales. Contemporary Drug Problems, 42(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450915569724

- Herzlich, C., & Pierret, J. (1989). The construction of a social phenomenon: AIDS in the French press. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 29(11), 1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90062-2

- Hirschovits-Gerz, T. (2013). How Finns perceive obstacles to recovery from various addictions. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 30(1–2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.2478/nsad-2013-0007

- Jauffret-Roustide, M., & Cailbault, I. (2018). Drug consumption rooms: comparing times, spaces and actors in issues of social acceptability in French public debate. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 56, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.014

- Jodelet, D. (1991). Madness and social representations: Living with the mad in one French community. University of California Press.

- Joffé, H. (1999). Risk and 'the other. Cambridge University Press.

- Joffé, H. (2003). Risk: From perception to social representation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276126

- Joffé, H., & Lee, N. L. (2004). Social representation of a food risk: The Hong Kong avian bird flu epidemic. Journal of Health Psychology, 9(4), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105304044036

- KAA 5/2020 vp. Kansalaisaloite Kannabiksen käytön rangaistavuuden poistamiseksi [Citizens’ initiative for decriminalising cannabis use]. https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/KasittelytiedotValtiopaivaasia/Sivut/KAA_5+2020.aspx

- Karjalainen, K., Pekkanen, N., & Hakkarainen, P. (2020). Suomalaisten huumeiden käyttö ja huumeasenteet – Huumeaiheiset väestökyselyt Suomessa 1992–2018. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (THL). Raportti 2/2020. PunaMusta Oy.

- Liu, J. H., & Sibley, C. G. (2013). From ordinal representations to representational profiles: A primer for describing and modelling social representations of history. Papers on Social Representations, 22(1), 5.1–5.30.

- MacDonald, R., & Marsh, J. (2002). Crossing the Rubicon: Youth transitions, poverty, drugs and social exclusion. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00004-X

- Manza, J., & Cook, F. L. (2002). A democratic polity? Three views of policy responsiveness to public opinion in the United States. American Politics Research, 30(6), 630–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/153267302237231

- Marková, I., & Wilkie, P. (1987). Representations, concepts and social change: The phenomenon of AIDS. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 17(4), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1987.tb00105.x

- Masyn, K. E. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods. Vol. 2. Statistical analysis (pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

- Moscovici, S. (1973). Introduction. In C. Herzlich (Ed.), Health and illness: A social psychological analysis (pp. ix–xiv). Academic Press.

- Moscovici, S. (1988). Notes towards a description of social representations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(3), 211–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180303

- Musher-Eizenman, D. R., Holub, S. C., & Arnett, M. (2003). Attitude and peer influences on adolescent substance use: The moderating effect of age, sex, and substance. Journal of Drug Education, 33(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2190/YED0-BQA8-5RVX-95JB

- Negura, L., & Plante, N. (2021). The construction of social reality as a process of representational naturalization. The case of the social representation of drugs. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 51(1), 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12264

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176

- O’Gorman, A. (2016). Chillin, buzzin, getting mangled, and coming down: Doing differentiated normalisation in risk environments. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 23(3), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1176991

- Parker, H., Williams, L., & Aldridge, J. (2002). The normalization of ‘sensible’ recreational drug use: Further evidence from the North West England longitudinal study. Sociology, 36(4), 941–964. https://doi.org/10.1177/003803850203600408

- Porcu, M., & Giambona, F. (2017). Introduction to latent class analysis with applications. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(1), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616648452

- Sakki, I., Menard, R., & Pirttilä-Backman, A. (2017). Sosiaaliset representaatiot: Yhteisön ja mielen välinen silta [Social representations: a bridge between community and mind]. In Ihmismielen sosiaalisuus [The social human mind]. (pp. 104–129). Gaudeamus.

- Shildrick, T. (2002). Young people, illicit drug use and the question of normalization. Journal of Youth Studies, 5(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260120111751

- Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2013). Relocating attitudes as components of representational profiles: Mapping the epidemiology of bicultural policy attitudes using latent class analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1931

- Small, D., Palepu, A., & Tyndall, M. W. (2006). The establishment of North America's first state sanctioned supervised injection facility: A case study in culture change. International Journal of Drug Policy, 17(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.08.004

- Staerklé, C. (2009). Policy attitudes, ideological values and social representations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(6), 1096–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00237.x

- Staerklé, C. (2011). Back to new roots: Societal psychology and social representations. In J. Valentim (Ed.), Societal Approaches in Social Psychology. (pp. 81–106). Peter Lang CH.

- Staerklé, C. (2013). The true citizen: Social order and intergroup antagonisms in political lay thinking. Papers on Social Representations, 22(1), 1.1–1.21.

- Tammi, T. (2005). Discipline or contain?: The struggle over the concept of harm reduction in the 1997 drug policy committee in Finland. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16(6), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.06.006

- Unlu, A., Demiroz, F., Tammi, T., & Hakkarainen, P. (2021). The complexity of drug consumption room policy and progress in Finland. Contemporary Drug Problems, 48(2),151–167.

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2013). Technical guide for Latent GOLD 5.0: Basic, advanced, and syntax. Statistical Innovations Inc.

- Williams, L. (2016). Muddy waters? Reassessing the dimensions of the normalisation thesis in twenty-first century Britain. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 23(3), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2016.1148118

- World Drug Report. (2019). United Nations publication, Sales No. E.19.XI.8.