Abstract

Background

Lately, there has been massive media coverage of gang-related criminality in ‘exposed areas’ in Sweden. Politicians have blamed the illegal drugs trade without questioning the country’s prohibitionist drug policy. This study analyzes how cannabis is constructed in Swedish newspaper articles that mention both organized crime and cannabis. We ask how the drug and its buyers and sellers are described, what discourses are drawn upon, and discuss the relationship between media coverage and drug policy.

Methods

We analyzed recent (2021) articles from four newspapers (n = 71) through Critical Discourse Analysis.

Results

Cannabis was constructed as a commodity linked to violence and deviance. Agency was attributed to people with power and status (e.g. gang leaders), and recreational cannabis users were described as guilty of feeding organized crime. A combination of economic and moral discourses was used to make the reported events meaningful, and to motivate both prohibition and decriminalization/legalization.

Conclusion

The study shows that assumedly neutral journalistic voices emphasized the link between cannabis and violence and problematized cannabis buyers and sellers. This homogenous media coverage will probably contribute to keep the question of cannabis law reform discursively lifeless in Sweden.

Introduction

Media shape people’s attitudes toward issues such as drugs (Lancaster et al., Citation2011; Lenton, Citation2004; Orsini, Citation2017; Taylor, Citation2008; Tieberghien, Citation2014), gang-related criminality (Weng & Mansouri, Citation2021; Yazgan & Utku, Citation2017), and immigration (Ekman & Krzyżanowski, Citation2021), and it affects the related political discourse (e.g. Altheide & Schneider, Citation2013; Orsini, Citation2017). It is therefore important to critically scrutinize media messages about social phenomena. In this study we analyze media where all the above issues combine in complex ways: Swedish newspaper articles on cannabis-related organized crime, which is often depicted as stemming from so called ‘exposed areas’ with large shares of immigrant populations. Previous research suggests that cannabis is constructed differently across contexts (Duff, Citation2017); it is a polysemic sign that can have various meanings (e.g. an effective medicine, a recreational drug or a market commodity). In line with this, we ask: 1) how the media at issue construct cannabis as a drug, 2) what characteristics sellers and buyers are attributed with, and 3) what discourses are drawn upon to provide reported events with meaning. Our ambition is also to discuss the relationship between this media coverage and Swedish restrictive drug policy.

During the past decade cannabis policies have become more lenient in many Western countries. These changes have been driven by concerns related to public health, criminal justice and economical aspects (EMCDDA, Citation2018; Hall & Lynskey, Citation2020), and different measures have been implemented, including decriminalization of personal possession and use, and legalization of medical and adult recreational cannabis use (Hall, Citation2020; Lévesque, Citation2023). While being illegal under international law, the production, trafficking, possession and use of cannabis is no longer only associated with organized crime and deviance in settings that have experienced cannabis law reform. Discourses centered on fair labor, consumer health and the environment have manifested in the cannabis sectors in these places as well, particularly in the US (Bennett, Citation2018).

In Sweden, cannabis has for a long time been at the heart of the drug policy, directing its development toward issues such as morality, legality and social problems and warranting a rejection of less strict regulations (Tham, Citation2021). Since the dawn of the national drug policy in the mid 1960s, there has been political consensus that all illicit drugs are inherently harmful and should be fought. Swedish drug policy is guided by the slogan ‘a drug-free society’ where experimental and street-level cannabis use is a key target (Tham, Citation2021). While cannabis is the most common illegal drug in Sweden, both regarding seizures (BRÅ, Citation2021a) and use (CAN, Citation2022), the prevalence of use is low compared to elsewhere in Europe (EMCDDA, Citation2022). A very minor increase has however been noted during the past 10 years (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Citation2020).

Due to the political goal of removing drugs from Sweden, as suggested by the notion of ‘a drug-free society’, cannabis has never been seen as a ‘soft’ drug. In contrast to for example Malta and (potentially) Germany (Fischer & Hall, Citation2022), Sweden is not moving towards cannabis law reform. In fact, the government announced in 2020 that it will not reconsider its prohibitionist line, including criminalized personal possession and use (see Andréasson et al., Citation2020).

Despite the change of government in 2022, the persistent strictness of Swedish drug policy is striking, as illustrated by a current political initiative to introduce harsher penalties for small scale drug sales as a way to tackle organized crime (Prop. 2022/23:53, Citation2023). The question of cannabis law reform is thus discursively lifeless in Sweden; it is met with elite ideological decisions rather than public debate about prevalence rates, harms and drug control costs (Lancaster, Citation2014; Wicklén, Citation2022).

However, there are pockets of resistance to this negative view on cannabis, particularly among users (e.g. Ekendahl et al., Citation2020; Sznitman, Citation2008). Månsson (e.g. 2014; 2016) has shown that the Swedish cannabis discourse during the mid-2010s did not portray cannabis as one specific drug with fixed characteristics, but rather several ‘versions’ of cannabis attached to conflicting political interests. While a juridical discourse dominated media coverage of cannabis for a long period of time (see e.g. Pollack, Citation2001), repeating the classic theme that all drug use is inherently bad (Orsini, Citation2017), some research suggests that Swedish media in the 2010s and onwards have ‘opened up’ somewhat, to include cannabis as a market commodity (Månsson, Citation2016), a potential medicine (Abalo, Citation2021) and advocacy for legalization (Abalo, Citation2019).

Still, research is scarce on what Swedish media make today of the recent political, professional and public focus on organized crime in so-called ‘exposed areas’, characterized by ‘low socioeconomic status where the criminals have an impact on the local community’ (Polisen, Citation2022, no pagination). In times of negative politicization of ‘exposed areas’, not seldom populated by immigrants (cf., Ekman & Krzyżanowski, Citation2021), it is essential to track whether the cannabis-organized crime link works to create a ‘moralistic “us and them” tone’ (Haines-Saah et al., Citation2014, p. 59) and ‘contemporary stereotypes about the racialized Other’ (Boyd & Carter, Citation2012, p. 253).

As in many other Western countries, Swedes find law and order a top important issue (Martinsson & Andersson, Citation2022), and political rhetoric equate being tough on crime with being tough on drugs (Taylor, Citation2008). While having previously been conceived of as a youth problem in Swedish cannabis discourse (Månsson & Ekendahl, Citation2015), lately, the drug appears to have increasingly been linked to problems with organized crime. Seminars for drug policy and prevention stakeholders have been launched on the relationship between drug abuse and organized crime (e.g. RFMA, Citation2021; U-FOLD, Citation2021). Moreover, during 2022, a scientific report from a reputable institute was released on cannabis and deadly violence (CES, Citation2022). It received a lot of media attention, in which a causal relationship between cannabis and violence was assumed (e.g. Erlandssson, Citation2022; Widestrand, Citation2022).

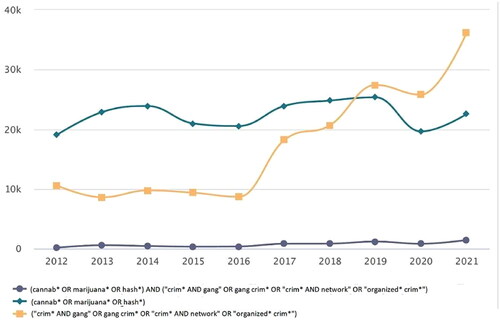

To concretize this discursive shift towards crime issues, we did a basic search in Retriever Mediearkivet (https://www.retriever.se/tag/mediearkivet/) which shows that articles on organized crime, and those that link it in some way to cannabis, have skyrocketed in the past decade. displays that the number of published Swedish media texts on organized crime has more than tripled between 2012 and 2021, with a major upward trend observed since 2016. During the same time period, the coverage of cannabis remained largely constant, while more rare texts where both organized crime and cannabis were mentioned increased dramatically (a tenfold increase from 141 to 1427).

Figure 1. Number of swedish news articles mentioning cannabis-related issues (rhombus), organized crime related issues (square) and both issues within the same article (circle). X-axis: time; Y-axis: number of hits in thousands.

It is thus obvious that Swedish media link cannabis to organized crime, but the essential elements of this coverage are unknown. In this study we use Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA, Fairclough, Citation1995) to study how contemporary media in Sweden associate cannabis with organized crime. We draw on and contribute to research on how media contribute to Othering and stereotypification of drug users (e.g. Boyd & Carter, Citation2012; Haines-Saah et al., Citation2014), to moral panics related to drugs (Fredrickson et al., Citation2019; Windle & Murphy, Citation2022), and to turning public attention to law and order (Orsini, Citation2017; Taylor, Citation2008).

Approach

Swedish discourse on organized crime and cannabis is located in the nexus of several sociocultural factors, such as media navigating between public service and market concerns (Fairclough, Citation1995, p. 66), restrictive drug policy (Tham, Citation2021), cannabis regulation trends (Lévesque, Citation2023), increases in deadly violence in Sweden (BRÅ, Citation2021b), ‘exposed areas’ as acute social concerns, as well as political agendas to win public opinion. Hence, it is relevant to use a discourse analytical tool that emphasizes the interplay between text and context. To achieve both breadth and detail, we approached print media by use of CDA (Fairclough, Citation1995). Fairclough assumes that spoken or written language is historically situated and has a dialectical relationship with the social. He (Fairclough, Citation1995, p. 55) writes:

Language use is, moreover, constitutive both in conventional ways which help to reproduce and maintain existing social identities, relations and systems of knowledge and belief, and in creative ways which help to transform them.

…the translation of official sources and official positions into colloquial discourse is to help legitimize these official sources and positions with the audience.

To scrutinize ‘communicative events’ such as newspaper articles, Fairclough (Citation1995) urges us to both describe how a text is constructed and interpret how it produces and reproduces discourse, power relations and social order. He also maintains that communicative events should be analyzed at three levels: the text level (e.g. vocabulary and semantics), the discourse practice level (e.g. what discourses and genres communicative events draw on and how they are produced and consumed), and finally the sociocultural practice level (e.g. issues of power, ideology and values).

The first level is covered here by using two well-known and useful tools for textual analysis, modality (see Fairclough, Citation1995) and transitivity (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2014). A focus on modality means analyzing the extent to which the journalistic voice makes truth claims and appears to agree with the views and propositions that are covered. We analyze transitivity by highlighting how people and actions are represented with particular focus on agentic power. Our main interest is in ‘who does what to whom’ (Li, Citation2010, p. 3447), which elucidates how articles allocate blame and responsibility in relation to organized crime and cannabis.

On the second level of analysis, we target what discourses are articulated in the articles. Discourse is here viewed as a system of knowledge and belief that constructs the world in a specific way, or as Fairclough (Citation1995, p. 56) states, ‘the language used in representing a given social practice from a particular point of view’. This conceptualization makes it possible to differentiate between for example medical (containing concepts and reasoning from the medical domain) and juridical (containing concepts and reasoning from the legal domain) discourses. The different article types are approached as examples of the generic genre of print media. While for example debate articles and news columns could be perceived as belonging to different genres, we treat them as analytically similar because both contribute to the total stock of media coverage. Lacking relevant data, we do not address the editorial processes that precede publication. Though this could provide valuable information about why articles are written and formatted in certain ways, it is beyond the scope of our analysis.

The third level of analysis is focused in the discussion, where we contextualize the media coverage by critically interpreting its interconnections with the sociocultural practice level, including an increased focus in Sweden on organized crime as the root cause of social problems, problematizations of immigrants and ‘exposed areas’, and a political landscape that by tradition safeguards restrictive drug policy. While CDA-analyses run the risk of overemphasizing the significance of words and formulations that might be coincidental, the methodology facilitates multifaceted and dense analyses of small but qualitatively rich data sets.

Data and method

To achieve geographical spread without making the data too extensive for qualitative analysis, we chose two newspapers based in the capital city of Stockholm (Dagens Nyheter, DN, and Svenska Dagbladet, SvD) with national reach, one that covers the western Gothenburg region (Göteborgs-Posten, GP) and one that covers southern Sweden (Sydsvenskan, SS). Three are independently liberal (DN, GP and SS) and one is unbound conservative (SvD).

In order to strategically sample articles that include both cannabis and gang-related issues, a Boolean search in Swedish Retriever Mediearkivet (www.retrievergroup.com) was conducted. We limited the search to the four newspapers and to Swedish edited and printed sources during 2021. To get a contemporary and quantitatively manageable sample we did not include a previous year for comparison. The following search string was used, but with Swedish terms: ‘(cannab* OR marijuana* OR hash*) AND (‘crim* AND gang’ OR gang crim* OR ‘crim* AND network’ OR ‘organiz* crim*’)’, yielding 75 hits, out of which four were about foreign issues and were excluded. The sample includes lengthy feature articles, news articles, news alerts, editorials and debate articles (number of articles: DN = 15; SvD = 23; GP = 24; and SS = 9). We do not analyze photographs, visuals or layout, but it should be noted that cannabis was shown in pictures or mentioned in headlines, bylines or locations in almost 40 per cent of the articles.

Tabloids and digital sources (such as online-only articles, web-TV and radio) are not covered, and not explicitly left-wing or small-scale regional newspapers (due to our focus on widely circulated urban press). These limitations aside, the sample contains four widely circulated newspapers and should give an adequate snapshot of how cannabis is depicted in contemporary media coverage of organized crime in Sweden.

Empirically, we first made an inductive content-based coding of the data, with codes such as ‘cannabis and violence’, ‘descriptions of buyers and sellers’, and ‘economic interests’. Thereafter, research question 1 (on how cannabis is constructed) was answered by scrutinizing the codes with focus on claims of objectivity and facts (modality). Research question 2 (on the characteristics of sellers and buyers) was answered through analyzing the allocation of agency and responsibility to actors in the data (transitivity). Finally, research question 3 (on what discourses are drawn upon) was elucidated through identifying concepts and reasoning that represent ‘a given social practice from a particular point of view’ (Fairclough, Citation1995, p. 56). This analytical process yielded three themes (one for each research question) that together represent our CDA-interpretation of the full material. We translated data extracts from Swedish to English.

Results

In the first theme we show that the journalistic voices constructed two main ‘versions’ of cannabis: as an illicit commodity linked to violence, and as a drug symbolizing deviance. The second theme illustrates that agency was assigned to those with power and status, which emphasized their responsibility. The third theme shows the combined economic and moral discourses that were used to attribute events with meaning and justify certain cannabis regulations.

Cannabis represents violence and deviance

The first ‘version’ of cannabis surfaces through accounts of police crackdowns and drug seizures by customs. The media coverage is dense with short records of events during which specified amounts of cannabis have been seized together with other drugs, luxury products, currency, explosives and firearms. This depicts cannabis as similar to other illegal drugs, and underscores its link to criminal gangs. A typical format is the listing of drug seizures and juridical indictments, as in DN (2021-03-22):

Three men in their 30s-40s linked to a stash of automatic firearms, detonators and 100 kg of explosives are currently on trial. Two of them have been linked to 42 kg of cocaine. A gang leader aged 38 and seven others are in custody for involvement in the planning of two killings. Two men, aged 28 and 31, have been prosecuted for running a gang that has smuggled large quantities of cannabis by lorry from Spain and motorboat from Denmark.

The same feature article (DN, 2021-03-22) iterates that cannabis is linked to violence by depicting how encrypted cell phone communication (Encrochat) facilitates crime. Of note is that the journalistic voice does not report on a factual but a fictional scenario:

The fact that customers are given anonymous aliases, and therefore are not forced to reveal their real identities, creates a sense of safety among customers. The discussions are getting more open. Who wants to join in on a cannabis shipment from Morocco? Anyone got explosives for sale? Who can supply a trustworthy guy for a contract killing? A user approached by DN during this time period is scared of the speed blindness Encrochat has allegedly created: - People sit at home on the couch and order killings. It’s sick.

We now turn to the other main ‘version’ of cannabis found in the material, as a consumable drug that signals deviance. Criminals with violent histories are recurrently depicted as both sellers and users of cannabis, which strengthens the cannabis-violence link in the data. One of the newspapers (GP, 2021-03-23) lists men accused of killing a gang leader. In some of these cases, cannabis use is presented as personal background, as in ‘male born 2001, charged with murder’ who has been ‘under the influence of drugs when stopped by police’:

During an interrogation in the summer of 2019 he said he smoked a joint every day. After being accused of handling an automatic weapon, he was prosecuted for aggravated weapons offense early 2019. He was acquitted.

The construction of cannabis as a consumable drug is moreover usually presented as belonging to ‘exposed areas’. In a feature article about two brothers (with names that do not signal traditional Swedish ethnicity) who got caught up in gang criminality, the drug is found at home by a worried mother. The mentioning of cannabis symbolizes a turning point, announcing when a dangerous criminal world entered an innocent family (SvD, 2021-12-11).

One night, after he had finally been allowed to go to a downtown concert, his mother discerned a weird smell when cleaning his room. - It smelled like the metro, I didn’t realize where it came from, but behind the radiator I found a small chunk of cannabis. I made an online search to understand what it was.

Occasionally the police officers turn silent to listen to the police radio. They open gates, illuminate elevator shafts–sometimes weapons are hidden above the elevator. A man hastily exits an entrance and [police officer] follows, a quick step to the side in order to–as he says–ascertain if the smell of hashish ‘lingers’. Many residents are bothered by smoke from hashish in stairwells.

Cunning criminals sell cannabis

Corresponding with previous research on media representations of drugs (e.g. Lancaster et al., Citation2011; Taylor, Citation2008), our analysis suggests that the individuals who populate media coverage of cannabis and organized crime are divided into heroes and villains. The first are law enforcement officers and policy stakeholders who try to stop brutal criminality. The second are those who traffic, sell and buy cannabis.

As evidenced by our analysis of transitivity, higher tier criminals are depicted as more agentic than lower tier criminals. Even though both groups are presented through their criminal deeds, higher tier and adult criminals are more explicitly cast as intentional and culpable (see also, Alexandrescu & Spicer, Citation2023 for a similar conclusion). They lure people into criminality, such as ‘young men’, ‘minors’, ‘boys’, ‘children’, and, as in the following extract from a short news article (SvD, 2021-07-10), ‘young people without prior records’:

The boys were tricked into selling drugs, primarily cannabis and tramadol, something they later on could not quit.

The new criminals, mainly with Middle Eastern roots, did not have the same solid violence capital–but so much more guns. When a 32-year-old leader was arrested with eight kg of hashish, five pistols hidden in a car were found as well. It was during this time children were being recruited as sellers and assistants. A drug dealer called them his ‘brats’, when prosecuted in [place] court. Some of the children rose through the ranks and recruited new minors.

- You get a message about hashish delivery from Morocco and if it is interesting you meet, get a sample and check that everything looks fine. If ok, it’s all about acting, because this stuff is peddled quickly.

Still, his major concern is probably the risk of upsetting the new generation of drug dealers. - I try to avoid them as much as I can, because as we know, it can go ballistic at any time.

Smuggling and revenues make it possible for the gangs to get to the core of societal functions. As with silencing and threatening nearby areas to protect sales, their trade routes also mean compromising freight companies, recruiting chemists, dock workers, IT-technicians, auto mechanics, lawyers, company agents and bankers. They monitor custom officers and emergency services. (…) An experienced perpetrator testifies: - There’s no hierarchy anymore. These suburban gangs are too unstructured. Previously, you met during conflicts and sorted things out. It’s impossible with these unstructured groups. It’s a whole new ball game.

Cannabis use feeds organized crime

The media coverage contains several references to terms such as value, supply, demand and income, illustrating that it draws on an economic discourse. Aligned with this discourse, cannabis is constructed as a commodity, which attributes the reported events of trafficking, sales and consumption with meaning. For example, short news articles/columns/alerts about drug seizures and smuggling regularly describe the market values of drugs. Similarly, more extensive feature articles use economic terms such as supply and demand to describe some criminals as rational entrepreneurs (also illustrated above):

Some of the buyers are quite frank and ask if cocaine is sold, then they meet at specific locations. The sellers have always been polite to customers. It is proper business.

This is the main income for gangs. When people buy cocaine or hashish they also de facto feed those who place bombs in stairwells. We know that many disputes in criminal milieus concern drugs. I hope and believe that it will make more people think twice.

Young cannabis users are described as hypocrites, since they are concerned with consumer power and environmental issues but disregard this when buying drugs:

Generation Z might be healthy idealists in many ways, but when they want to get high their conscientiousness is all gone. (…) Unfortunately, young people are not alone in disregarding their consumer power. (…) While the climate issue has an inflated focus on individual responsibility in the form of meat and flight shame, it is wholly non-existent in the drug business, in which shame would really be in order.

The economic discourse drawn upon to allocate responsibility is also articulated in debate articles arguing for cannabis law reform. In the quote below, a left-wing youth party league suggests that Sweden should consider decriminalization of personal use of illegal drugs (SvD, 2021-07-27):

If one is sincere and truly wants to crush organized crime and reduce drug-related mortality, then politics must take responsibility and evaluate the current situation and our legislation, says [person].

If we would take the route of liberalizing and legalizing, suggested by some, then cannabis use would increase in Sweden. That would be a huge gift to the criminal gangs dealing with these drugs. That is not the route to take. (…) All drugs sold on the streets will feed the gangs one way or the other, [person] says.

Discussion

This study provides insights into recent years’ public and political focus on organized crime, and how this is discursively linked to cannabis in Sweden. The quantitative illustration of the past decade’s increase in articles that mention both organized crime and cannabis () suggests that Swedish media promote the idea that cannabis is an important source of revenue for criminal networks, as advanced by for example Europol (Europol, Citation2021). This is obviously not problematic per se. However, other types of reporting are possible, such as focusing less on the particular role of cannabis in the illegal drugs trade, less on the drug as a cause of violence and less on its users as deviant criminals. According to our interpretation, journalists’ tendency to highlight cannabis in crime-related events sits well in a prohibitionist drug policy because it ‘legitimize(s) these official sources and positions’ (Fairclough, Citation1995, p. 73). It provides a discursive counterweight to the less problem-oriented coverage of cannabis that has surfaced lately in Swedish media (Abalo, Citation2019, Citation2021; Månsson, Citation2016).

We have shown that the analyzed newspapers constructed two ‘versions’ of cannabis: as an illicit commodity interlocked with violence, and as a drug symbolizing deviance. The articles assigned agency to those already in power (e.g. gang leaders) and those with assumed social status (e.g. middle-class recreational users), which emphasized their responsibility and lack of morals. While the articles were selected based on their mentions of the drug and organized crime, they appear to illustrate a shift in how cannabis is framed in contemporary Swedish newspapers. Rather than leaning towards global cannabis law reform trends (Hall, Citation2020; Lévesque, Citation2023), the analyzed media coverage advances a ‘new’ cannabis discourse. This discourse encompasses a mix of economic and moral vocabulary much less concentrated on traditional social problems than before (Månsson, Citation2016).

To further the understanding of this development we need to relate the results to what Fairclough (Citation1995) calls the sociocultural practice level. Organized crime has become pivotal in Sweden, and political parties currently compete on who is toughest. This reflects the drug policy debate of the 1980s when political parties in Sweden jointly took steps toward zero-tolerance. In this ‘tango politics’ (Lenke & Olsson, Citation2002, p. 70), all positioned themselves as close as possible to each other, reaching a point when voters could no longer determine who was ‘leading the dance’. A similar ‘tango’ has been identified regarding immigration, where a negative politicization of immigrants was introduced by the national-conservative party Sweden-Democrats, soon to be followed by other political parties (see e.g. Krzyżanowski, Citation2018). Previous research has shown that the media increasingly normalize radical perceptions of immigration, stating for example that it is ‘one of the plausible reasons for an increase in various forms of crime, such as gang violence in Sweden’ (Ekman & Krzyżanowski, Citation2021, p. 79).

It is therefore not surprising that this study demonstrates a field characterized by moral panic (Fredrickson et al., Citation2019), articulated via the discursive link between immigrant populations and organized crime, with cannabis being a ‘mediator’. This crime-immigrant nexus (Schclarek Mulinari, Citation2017) is now interwoven with a crime-drug nexus, showcasing a seamless association between organized crime, drugs and immigration. This is embodied by the ‘fearful other’, that is, people engaged in the cannabis sector who are ‘constructed as apart’ from the conscientious, white, ordinary citizen (Ahmed, Citation2004, p. 126).

Historically, Sweden has experienced similar discursive processes that have contributed to the strong repudiation of illegal drugs. It is often stated that the link between the ‘fearful other’ (e.g. criminals, young people) and drugs (e.g. amphetamine, cannabis) steered the formulation of the modern drug problem in the 1960s (Olsson, Citation2011). The crime-drug-immigrant nexus delineated in this study reinforces this old problematization. The moral rejection of new variants of the ‘fearful other’ spills over to associated drugs, legitimizing the construction of cannabis as deviance, violence and danger.

The notion of cannabis as a cog in the illegal drugs trade, and the ruthlessness of the criminals who run it, similarly legitimizes organized crime as a pressing social concern in Swedish society. This also warrants the allocation of responsibility to all involved in the ‘Ongoing Fight’ (Orsini, Citation2017, p. 204) and the construction of recreational users as blameful hypocrites (see also, Friis Søgaard & Søgaard Nielsen, Citation2021). In contrast to users who are described as marginalized or vulnerable (Alexandrescu & Spicer, Citation2023), this group is made to represent people with high standards and abilities, who are expected to act better. Research shows that illicit substance use can be understood as a rational pursuit of pleasure (e.g. Duff, Citation2014; Moore, Citation2008), and the framing of users as consumers who should not be left to illegal markets is an important argument in the international cannabis legalization movement (see e.g. Cormack & Cosgrave, Citation2022). The current Swedish media coverage, however, does not construct drug users as sufferers of problems with organized crime, but rather as their root cause.

Our analysis shows that the link assumed in the media between cannabis and violence motivates two different cannabis policy responses: both continued prohibition and law reform. However, (the rare) discussions about more lenient policies hardly ever centered on increasing the wellbeing of cannabis users, through for example reducing stigma and contacts with illegal markets. The minimal attention paid towards issues of public health and human rights illustrates the leverage of the combination of economic and moral discourses in attributing cannabis with meaning in contemporary Sweden.

To conclude, it appears as if the intimate relationship between cannabis and organized crime advanced by Swedish print media strengthens rather than challenges the traditional negative politicization of cannabis. Even though political youth party leagues recommend cannabis law reform, there is still consensus on continued prohibition among the elite; the drug has not been ‘hegemonised by a specific party or ideology’ (Månsson, Citation2014, p. 679). Media’s influence on agenda setting, public opinion and politics is obvious (Lancaster et al., Citation2011; Orsini, Citation2017), from which follows that its recent spotlight on cannabis-related gang violence disturbs those who want Sweden to abandon the idea of ‘a drug-free society’. With cannabis conceived of as a high-profile problem (Månsson & Ekendahl, Citation2015), a prohibitionist hegemony, and a public debate on law and order (Martinsson & Andersson, Citation2022), understandings of cannabis that do not draw on juridical, social problem or economic-moral discourses are easily marginalized as they fit poorly with the ideological foundations of Swedish drug policy (see Lancaster, Citation2014). This may be one of several explanations as to why the question of cannabis law reform continues to be politically dead in Sweden. Research should continue to track how the cannabis discourse evolves over time, with a focus on how and where resistance to prohibition is developed and disseminated. The naturalized and often stereotypical problematization of cannabis among key stakeholders in political, professional and also media domains (Global Commission on Drug Policies, Citation2017), augmented by its discursive link to organized crime, will probably contribute to status quo rather than reform in Swedish drug policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abalo, E. (2019). Rifts in the hegemony: Swedish news journalism on cannabis legalization. Journalism Studies, 20(11), 1617–1634. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1533416

- Abalo, E. (2021). Between facts and ambiguity: Discourses on medical cannabis in Swedish newspapers. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift: NAT, 38(4), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072521996997

- Ahmed, S. (2004). Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117

- Alexandrescu, L., & Spicer, J. (2023). The stigma-vulnerability nexus and the framing of drug problems. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 30(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2022.2049214

- Altheide, D. L., & Schneider, C. J. (2013). Qualitative media analysis. (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Andréasson, S., Fries, B., Guterstam, J., Gynnå Oguz, C., Hammarberg, A., Heilig, M., (…) Wallhed Finn, S. (2020). Varför denna rädsla för att utvärdera? [Why this fear of evaluating?]. Svenska Dagbladet. https://www.svd.se/a/zGv7wO/varfor-denna-radsla-for-att-utvardera

- Bennett, E. A. (2018). Prohibition, legalization, and political consumerism: Insights from the US and Canadian Cannabis markets. In M. Boström, M. Micheletti & P. Oosterveer (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism. Oxford University Press.

- Boyd, S., & Carter, C. (2012). Using children: marijuana grow-ops, media, and policy. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 29(3), 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2011.603133

- BRÅ. (2021a). Narkotikamarknader [Drug markets]. Rapport 2021:10. Brottsförebyggande rådet.

- BRÅ. (2021b). Dödligt skjutvapenvåld i Sverige och andra europeiska länder [Deadly gun violence in Sweden and other European countries]. Rapport 2021:8. Brottsförebyggande rådet.

- CAN. (2022). Användning och beroendeproblem av alkohol, narkotika och tobak [Use and addiction of alcohol, drugs and tobacco]. En studie med fokus på år 2021 i Sverige. CAN Rapport 209. Centralförbundet för alkohol- och narkotikaupplysning.

- CES. (2022). Inslag av cannabis vid dödligt våld i Stockholm och i Sverige [Elements of cannabis in deadly violence in Stockholm and Sweden]. Rapport 2022:1. Centrum för epidemiologi och samhällsmedicin. www.folkhalsoguiden.se

- Cormack, P., & Cosgrave, J. (2022). ‘ Enjoy your experience’: Symbolic violence and becoming a tasteful state cannabis consumer in Canada. Journal of Consumer Culture, 22(3), 635–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540521990876

- Duff, C. (2014). The place and time of drugs. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(3), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.014

- Duff, C. (2017). Natures, cultures and bodies of cannabis. The Sage Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Studies, 1, 679–693. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921986

- Edman, J. (2013). The ideological drug problem. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 13(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/17459261311310808

- Ekendahl, M., Månsson, J., & Karlsson, P. (2020). Cannabis use under prohibitionism–the interplay between motives, contexts and subjects. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 27(5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2019.1697208

- Ekman, M., & Krzyżanowski, M. (2021). A populist turn?: News editorials and the recent discursive shift on immigration in Sweden. Nordicom Review, 42(s1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2021-0007

- EMCDDA. (2018). Cannabis legislation in Europe: an overview. Publications Office of the European Union.

- EMCDDA. (2022). European drug report 2022: Trends and developments. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/14644/TDAT22001ENN.pdf

- Erlandssson, Å. (2022). Rapport. Cannabis driver på dödligt våld [Report. Cannabis drives deadly violence], Dagens Nyheter. https://www.dn.se/sverige/rapport-cannabis-driver-pa-dodliga-gangvaldet/

- Europol. (2021). Crime areas: cannabis. https://www.europol.europa.eu/crime-areas-and-statistics/crime-areas/drug-trafficking/cannabis

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Media Discourse. Edward Arnold.

- Fischer, B., & Hall, W. (2022). Germany’s evolving framework for cannabis legalization and regulation: Select comments based on science and policy experiences for public health. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, 23, 100546.

- Fredrickson, A., Gibson, A. F., Lancaster, K., & Nathan, S. (2019). “Devil’s Lure Took All I Had”: Moral Panic and the Discursive Construction of Crystal Methamphetamine in Australian News Media. Contemporary Drug Problems, 46(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918823340

- Friis Søgaard, T., & Søgaard Nielsen, F. (2021). Gang talk and strategic moralisations in Danish drug policy discourses on young and recreational drug users. In H. Tham (Ed.), Retreat or Entrenchment? Drug Policies in the Nordic Countries at a Crossroads (pp. 161–181). Stockholm University Press.

- Global Commission on Drug Policies. (2017). The world drug (perception) problem, countering prejudices about people who use drugs. 2017 Report. www.GCDP-Report-2017_Perceptions-ENGLISH.pdf (globalcommissionondrugs.org)

- Haines-Saah, R. J., Johnson, J. L., Repta, R., Ostry, A., Young, M. L., Shoveller, J., Sawatzky, R., Greaves, L., & Ratner, P. A. (2014). The privileged normalization of marijuana use–an analysis of Canadian newspaper reporting, 1997–2007. Critical Public Health, 24(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.771812

- Hall, W. (2020). The costs and benefits of cannabis control policies. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 22(3), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/whall

- Hall, W., & Lynskey, M. (2020). Assessing the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use: the US experience. World Psychiatry : official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 19(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20735

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. (2014). An introduction to functional grammar. Routledge.

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2018). ‘ We are a small country that has done enormously lot’: the ‘refugee crisis’ and the hybrid discourse of politicizing immigration in Sweden. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16(1-2), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1317895

- Lancaster, K. (2014). Social construction and the evidence-based drug policy endeavour. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(5), 948–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.002

- Lancaster, K., Hughes, C. E., Spicer, B., Matthew-Simmons, F., & Dillon, P. (2011). Illicit drugs and the media: Models of media effects for use in drug policy research. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(4), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00239.x

- Lenke, L., & Olsson, B. (2002). Swedish drug policy in the twenty-first century: A policy model going astray. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 582(1), 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620258200105

- Lenton, S. (2004). Pot, politics and the press—reflections on cannabis law reform in Western Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230410001704226

- Lévesque, G. (2023). Making sense of pot: conceptual tools for analyzing legal cannabis policy discourse. Critical Policy Studies, 17(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2022.2044874

- Li, J. (2010). Transitivity and lexical cohesion: Press representations of a political disaster and its actors. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(12), 3444–3458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.04.028

- Månsson, J. (2014). A dawning demand for a new cannabis policy: A study of Swedish online drug discussions. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(4), 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.04.001

- Månsson, J. (2016). The same old story? Continuity and change in Swedish print media constructions of cannabis. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0021

- Månsson, J., & Ekendahl, M. (2015). Protecting prohibition: The role of Swedish information symposia in keeping cannabis a high-profile. Problem. Contemporary Drug Problems, 42(3), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450915599348

- Martinsson, J., & Andersson, U. (2022). Svenska Trender 1986–2017 [Swedish Trends 1986–2017], SOM Institutet, Göteborgs universitet. https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2022-04/1.%20Svenska%20trender%201986%20-%202021.pdf

- McAra, L., & McVie, S. (2016). Understanding youth violence: The mediating effects of gender, poverty and vulnerability. Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.02.011

- McCall, P. L., Parker, K. F., & MacDonald, J. M. (2008). The dynamic relationship between homicide rates and social, economic, and political factors from 1970 to 2000. Social Science Research, 37(3), 721–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.09.007

- Moore, D. (2008). Erasing pleasure from public discourse on illicit drugs: On the creation and reproduction of an absence. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 19(5), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.07.004

- Oppenheim, M. (2018). Middle class people taking cocaine at dinner parties should feel ‘guilty and responsible’ over street stabbings, says justice secretary. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/middle-class-cocaine-street-stabbings-responsible-david-gauke-knife-crime-a8371521.html

- Olsson, B. (2011). Narkotikaproblemet i Sverige: framväxt och utveckling [The Swedish drug problem: growth and development]. In B. Olsson (Ed.), Narkotika: Om problem och politik (pp. 23–42). Norstedts Juridik AB.

- Orsini, M. M. (2017). Frame analysis of drug narratives in network news coverage. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44(3), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450917722817

- Polisen. (2022). https://polisen.se/om-polisen/polisens-arbete/utsatta-omraden/

- Pollack, E. (2001). En studie i medier och brott [A study of media and crime]. [Doctoral thesis in Journalism]. Stockholm University, Department for Journalism, Media, and Communication.

- Prop. 2022/23:53 (2023). Skärpta straff för brott i kriminella nätverk [Harsher penalties for crimes in criminal networks]. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/proposition/2023/01/prop.-20222353/

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2020). Kunskapsläget om cannabis och folkhälsa i korthet [Summary of the state of knowledge on cannabis and public health], Number 19072. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publikationer-och-material/publikationsarkiv/k/kunskapslaget-om-cannabis-och-folkhalsa-i-korthet-/?pub=67820

- RFMA. (2021). Narkotikapolitik och förebyggande insatser [Drug policy and prevention]. Riksförbundet mot alkohol- och narkotikamissbruk. Conference held 21-10-13, https://rfma.se/uncategorized/rfmas-digitala-konferens-narkotikapolitik-och-forebyggande-insatser/

- Schclarek Mulinari, L. (2017). Contesting Sweden’s Chicago: why journalists dispute the crime image of Malmö. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(3), 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1309056

- Spicer, J. (2021). Between gang talk and prohibition: The transfer of blame for County Lines. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 87, 102667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102667

- Sznitman, S. R. (2008). Drug normalization and the case of Sweden. Contemporary Drug Problems, 35(2-3), 447–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090803500212

- Taylor, S. (2008). Outside the outsiders: Media representations of drug use. Probation Journal, 55(4), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550508096493

- Tham, H. (2021). On the possible deconstruction of the swedish drug policy. In H. Tham (Ed.), Retreat or Entrenchment? Drug Policies in the Nordic countries at a crossroads (pp. 129–158). Stockholm University Press.

- Tieberghien, J. (2014). The role of the media in the science-policy nexus. Some critical reflections based on an analysis of the Belgian drug policy debate (1996–2003). The International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(2), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.05.014

- U-FOLD. (2021). Gängkriminalitet, missbruk och framtidstro [Gang criminality, drug abuse and future hope]. Uppsala universitet, Forum för forskning om läkemedels- och drogberoende. Conference held 21-11-23. https://www.ufold.uu.se/evenemang/seminarier/hostseminarium21/

- Weng, E., & Mansouri, F. (2021). ‘Swamped by Muslims’ and facing an ‘African gang’problem: racialized and religious media representations in Australia. Continuum, 35(3), 468–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2021.1888881

- Wicklén, J. (2022). Vi ger oss aldrig. Så gick det till när Sverige förlorade kriget mot knarket. [We never give up. This is how Sweden lost the war on drugs]. Volante.

- Widestrand, K. (2022). Oftare cannabispåverkan vid dödligt våld [Cannabis influence more common during deadly violence], Svenska Dagbladet. https://www.svd.se/a/k6Lg6A/oftare-cannabispaverkan-vid-dodligt-vald

- Windle, J., & Murphy, P. (2022). How a moral panic influenced the world’s first blanket ban on new psychoactive substances. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 29(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1902480

- Yazgan, P., & Utku, D. E. (2017). News discourse and ideology: critical analysis of Copenhagen gang wars’ online news. Migration Letters, 14(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v14i1.322

Referenced print media

- DN (2021-02-02). Offensiv mot svenska gäng i Spanien: 40-tal gripna. [Crackdown against Swedish gangs in Spain: approximately 40 people arrested].

- DN (2021-02-23). Samhället gjorde allt för att rädda 16-åringen - ändå slutade det i mord [Society did everything it could to save the 16-year-old–it ended up in murder anyway].

- DN (2021-03-22). Akuta dödshot förde Sverige in i topphemlig polisoperation. [Acute death threats brought Sweden into a highly classified police operation].

- GP (2021-03-23). Här är alla de misstänkta i Gamlestadsärendet. [Here are all the suspects in the Gamlestad case].

- GP (2021-05-13). Regeringen: All droghandel göder gängen. [The government: All drug trade feeds the gangs].

- GP (2021-06-15). Hembesök av polis väntar för kokainköpare. [Police house calls await cocaine buyers].

- GP (2021-10-18). Hovrätten friar gängledare trots chat om knarkaffärer. [Court of appeal acquits gang member despite chat about drug deals].

- SS (2021-06-16). När idealisterna vill bli höga är moralen glömd. [When idealists are looking to get high moral standards are forgotten].

- SvD (2021-06-22). Köper man kokain har man blod på händerna.[If you buy cocaine you have blood on your hands].

- SvD (2021-07-10). Tvingade barn att sälja knark. [Forced children to sell drugs].

- SvD (2021-07-27). Intern strid i S när SSU avviker i narkotikafrågan. [Internal fights within the Social Democratic Party when youth league deviates in the drug question].

- SvD (2021-08-14). Här är våldets drivkrafter - från kokaodlingar till svenska gator. [Here are the drivers of violence–from coca cultivation to Swedish streets].

- SvD (2021-09-04). Drogberoende parallellsamhälle. [A drug addicted parallel society].

- SvD (2021-12-05). Tunga blå linjen. [Hardcore blue commuter line].

- SvD (2021-12-11). ‘Saker skulle hända om vita killar börjat skjuta’. [Things would happen if white boys started shooting].

- SvD (2021-12-16). ‘Därför är det rätt att legalisera cannabis’ [Why it is right to legalize cannabis].