ABSTRACT

The use of Instagram is becoming increasingly popular among students. Excessive Instagram use (EIU) has become a growing problem that can impact students’ lives psychosocially. This study applied uses and gratifications theory (UGT) to explore the impact of social gratification, content gratification, and entertainment along with social presence, and escapism in relation to EIU. Data were collected from 285 university students and analyzed in two steps. In the first step, structural equation modeling was employed to identify the important variables that impact excessive Instagram use. In the second step, an artificial neural network (ANN) technique was used for validating the findings in Step 1 and determined the relative importance of each variable in relation to excessive Instagram use. The results showed that social gratification, entertainment, escapism, and social presence were positively related to EIU. ANN analysis showed that escapism was the most important construct in predicting excessive Instagram use followed by entertainment, social presence, and social gratification. Furthermore, EIU was related to academic impairment. The findings of the study contribute to the domain of the dark side of online activities by theoretically investigating the effect of EIU on students’ academic study.

1. Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) have become a crucial part of young adults’ day-to-day activities. This is due to the variety of SNS activities that give them a great opportunity to interact with other users, making new friendships, and engage with brands. There are many positives gained from social networking such as study support (Tower et al., Citation2014), communication, collaboration, and information gathering (Kitsantas et al., Citation2016; Mazman & Usluel, Citation2010; Mirabolghasemi et al., Citation2016). However, for a small minority, there have been reported negative outcomes from SNSs including that concerning educational information system research (Cao et al., Citation2018). SNSs play a central role in the lifestyle of today’s online users, especially among students. Several studies have emphasized the significant role of SNS platforms, such as Facebook, in the educational process (Ainin et al., Citation2015; Hamade, Citation2013; Mirabolghasemi et al., Citation2016). Students can leverage the features of SNS platforms for group discussion, managing group projects, discussing assignments, and improving interaction with lectures (Helou, Citation2014). Tower et al. (Citation2014) found that Facebook group was an effective method for students to support their study, advance their peer learning, and encourage them to interact with academics. Similarly, Junco et al. (Citation2011) conducted a semester-long experimental study to examine the efficacy of using Twitter for academic purpose such as co-curricular discussions. The participants were split into two samples; the experimental sample, where students used Twitter as part of the class discussion, and the group sample, where students did not use Twitter. The results showed that students involved in the experiment group sample had a significant increase in their engagement with class discussion and semester grades compared to the control group sample.

Although the use of SNS platforms is not problematic for most people, recently, the number of users who engage in SNSs excessively or compulsively has become of increasing concern to researchers (e.g. Andreassen et al., Citation2017; Ershad & Aghajani, Citation2017). Moreover, with most SNS platforms being easy to access, many students spend more time engaging with them than with their academic study (Giunchiglia et al., Citation2018; Idris & Hasan, Citation2019). However, studies have shown that this excessive use can negatively affect students’ well-being (Cao et al., Citation2018; Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019), academic performance (Junco, Citation2012b; Kirschner & Karpinski, Citation2010), and lead to addictive behavior (Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019). For example, a study conducted in the Malaysian university context found that 88% of students use SNSs to socialize and interact with one another on a daily basis (Yusop & Sumari, Citation2013). Moreover, research by Alwagait et al. (Citation2017) found that students’ lack of time management when using SNSs was the main reason for weak academic performance.

The negative consequences of excessive SNS use on mobile devices are arguably underexplored (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, Citation2017; Zheng & Lee, Citation2016) but has grown greatly over the past few years. Among the studies that have been carried out, the overwhelming majority focus on Facebook users, and only a few studies have examined excessive Instagram use (EIU) (e.g. Kircaburun & Griffiths, Citation2018; Ponnusamy et al., Citation2020). The few previous studies empirically investigating the negative outcomes of EIU have examined such areas as romantic relationship outcomes (Ridgway & Clayton, Citation2016), addiction potential (Kircaburun & Griffiths, Citation2018), technology-family conflict (Zheng & Lee, Citation2016), and online compulsive buying (Pahlevan Sharif & Yeoh, Citation2018). In addition, studies have shown that EIU is associated with psychological and mental health issues such as depression (Donnelly, Citation2017), trait anxiety, and neuroticism (Balta et al., Citation2020). However, few studies examined the association between EIU and academic impairment of students (Cao et al., Citation2018; Ponnusamy et al., Citation2020).

Recent studies have reported that Instagram is one of the fastest growing SNSs and is very popular among students compared to other SNSs such as Facebook and Twitter (Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017; Shane-Simpson et al., Citation2018). Studies have shown that young adults between 18 and 29 years represent approximately 59% of Instagram’s active users (Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017; Ponnusamy et al., Citation2020). This is likely because features such as the built-in filter allow users to filter their photos and the “live stream” feature which enables users to broadcast live videos. Because college students are extremely driven by their smartphones, using such features can sometimes lead to frequently share photos and videos, excessively checking the number of likes and comments on their posts, and constantly examining other friends’ online profiles (Kircaburun & Griffiths, Citation2018).

Although SNS platforms have many similar features, each platform has unique features, a different structure, and different stimuli and gratification factors (Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017). For example, Facebook has variety of functions that allow users to share text, video, photos, live locations, and emotion status (Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017). Twitter is a more text-based information-sharing platform, while Instagram (as previously mentioned) is more photo-based. Therefore, user behavior may differ from one platform to another (Ponnusamy et al., Citation2020). The excessive use of these features can result in psychological problems such as addiction among a minority of users (Gao et al., Citation2017; Kircaburun & Griffiths, Citation2018). However, there is little research on excessive Instagram use. Previous studies have examined addictive use rather than excessive use (Ershad & Aghajani, Citation2017; Foroughi et al., Citation2021; Kircaburun & Griffiths, Citation2018; Ponnusamy et al., Citation2020). A recent study by Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) noted that there was a need for more empirical investigation to other SNS platforms (e.g. Instagram) to understand the factors related to excessive and addictive use. Moreover, Ponnusamy et al. (Citation2020) highlighted that Instagram use reached to addiction level among adolescent, and assert that there is a need for more research to investigate which factors could lead to this among university students. Related to this, there is also a need for investigating the potential factors associated with EIU, examining the effect of EIU on students’ academic impairment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides details about the concept of excessive use of Instagram. Section 3 describes the theoretical foundation of the study by highlighting the importance of the uses and gratifications theory (UGT) in the use of social networking sites. Section 4 describes the research model and development of the hypotheses. Section 5 illustrates the details of the research method used to conduct the study. Section 6 provides details of the results of the data analysis. Section 7 reports the key findings, discussion, and theoretical and practical implications. Finally, Section 8 provides the study conclusions.

2. Excessive Instagram use

As aforementioned, the use of Instagram is rapidly expanding, and has become very popular among students (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). Instagram features allow users to frequently share photos and videos which leads some individuals to continuously check notifications on their shared photos and videos. Recently, Instagram has introduced new shopping tools that provide users with entertainment and utility, which results in greater intensity to follow new accounts and spend longer hours on the site (Casaló et al., Citation2017; Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019). Excessive use of SNSs is often defined as the extent to which SNS use (e.g. Instagram use) is much longer than the time the individual planned (Caplan & High, Citation2006; Zheng & Lee, Citation2016). However, the term “excessive” can mean different things to different people and is ultimately subjective.

The main difference between excessive use and addiction is that excessive use may not result in any negative consequences (Griffiths, Citation2005) whereas addiction is associated with an uncontrolled amount of time spent on the activity leading to major negative psychosocial impacts (Cao et al., Citation2018; Griffiths, Citation2005; Zheng & Lee, Citation2016). However, numerous studies have confirmed that excessive use for some individuals can also lead to negative consequences in real-life areas (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019; Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019). Romero-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2020), highlighted that the irresponsible use of SNSs can result in problematic use. On the other hand, Shaw and Black (Citation2008) defined addiction as “poorly controlled preoccupations, urges or behaviours regarding computer use and internet access that lead to impairment or distress”. Previous studies have characterized addictive behavior, including SNS addiction, as any behavior that features the six core components of addiction (i.e. mood modification, salience, tolerance, conflict, withdrawal, and relapse) (Griffiths et al., Citation2014; Hawi & Samaha, Citation2017; Ryan et al., Citation2014).

One of the most significant negative consequences is that excessive use can be a source of addiction for a minority of individuals (Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, SNS addiction (including Instagram addiction) is defined as “a user’s psychological state of dependence on the use of a social networking website which is manifested through an obsessive pattern of seeking and using this website; and these behaviors take place at the expense of other important activities” (Turel et al., Citation2011, p. 1). Therefore, the main difference between excessive use and addiction is that Instagram addiction occurs when the users have a problematic dependency on Instagram use (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019; Sanz-Blas et al., Citation2019). In this context, Sanz-Blas et al. (Citation2019) found that Instagram overuse and addiction are different constructs and the study found that higher Instagram overuse can lead to addiction.

Previous studies have attempted to identify the main reasons for EIU and its consequences. Sanz-Blas et al. (Citation2019) found that excessive Instagram use had a direct effect on addiction due to the lack of over users’ control of time spent on Instagram, which eventually impacted users’ emotional fatigue and stress. Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) found that problematic Instagram use was associated with the frequency of live steam watching, commenting on other posts, and liking. Another reason that may underlie excessive Instagram use is the fear of missing out (FoMO) (BBC, Citation2018; Glazzard & Stones, Citation2019). FoMO is a relatively new concept which refers to “a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent” (Przybylski et al., Citation2013, p. 1841). A recent study by Rozgonjuk et al. (Citation2020) examined the effect of FoMO on SNS use disorder and impact on daily life, and affirmed the central role of FoMO in SNS use disorder (which could include Instagram use). Overall, the research confirms that as Instagram has become a common daily activity, excessive daily use may trigger negative consequences, which may affect user’s self-control of Instagram usage and lead to addictive behavior for a small minority. However, these studies focus mainly on the consequence of excessive use and examine the effect of user’s personality factors such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, and daily internet use. However, there is little literature examining the gratification that may be generated from EIU.

3. Theoretical foundations

3.1. Uses and gratification theory

UGT was first introduced by Katz et al. (Citation1974) to explain how and why individual’s needs are gratified by specific media. UGT is defined as “ the social and psychological origins of needs which generate expectations of the mass media and other sources which lead to differential patterns of media exposure (or engagement in other activities) resulting in needs gratifications and other consequences, perhaps mostly unintended ones” (Katz et al., Citation1974, p. 510). UGT explains the user-level view of mass media such as the internet use. According to UGT, users are goal-oriented in their media selection, and they expose and integrate media messages within their everyday life to achieve maximum gratification (Phua et al., Citation2017). Every medium offers different combinations of characteristic content, typical attributes, and typical exposure situations (Katz et al., Citation1974). UGT research suggests that individuals use media for content carried by a medium such as information or entertainment, or they use media for the experience of media use (Stafford et al., Citation2004). In addition, social motivation is considered as the main usage factor motivating internet use (Stafford & Gillenson, Citation2004). According to Katz et al. (Citation1974), individuals’ gratification is derived from at least three sources: media content, exposure to media, and the social context that influences the exposure to different media.

In earlier research of UGT, when the focus was on traditional media such as television and newspapers, UGT was conceptualized as having two main categories: content gratification and process gratification. Content gratification refers to how users employ specific media due to its attractive content in the medium (e.g. information, entertainment material) (Islam et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2018). Process gratification refers to how users gain gratification from the experience of using particular media (Li et al., Citation2018). Recently, with the growth of internet use among individuals, social gratification has been introduced as a new dimension of UGT to represent user satisfaction with the media’s social environment that is not described in content and process gratifications (Li et al., Citation2018; Stafford et al., Citation2004). In this context, previous studies have considered UGT as one of the most effective frameworks in understanding the motivations that bring individuals to use specific media (Chang, Citation2018; Stafford et al., Citation2004), including SNS platforms (Al-Jabri et al., Citation2015; Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017).

4. Research model and hypotheses development

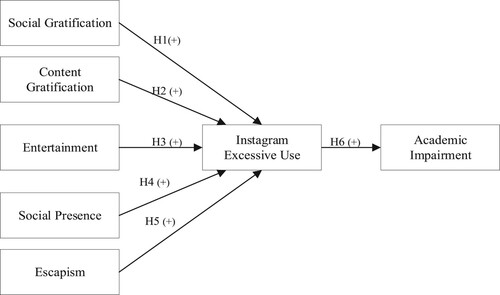

Drawing on UGT and the empirical literature, the present paper proposes a research model contending that social gratification, content gratification, entertainment, escapism, and social presence positively influence EIU. The model () also examines the positive effect of EIU on students’ academic performance.

4.1. Social gratification

Social gratification has been defined as the extent to which users are satisfied with the social environment (Stafford et al., Citation2004). Researchers have asserted that social interaction among users is the key motive to their social needs (Boyd & Ellison, Citation2008). Since Instagram is mainly used for social interaction and self-expression, it enables users to share their life story through the uploading of photos. Previous studies have suggested that social interaction is the main motivational factor for Instagram use in establishing and maintaining relationships (Kim et al., Citation2017; Lee, Lee, et al., Citation2015). Instagram has recently offered new features that enable the users to create and share live stories with their followers (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). Therefore, these social gratification activity may develop a sense of belonging to Instagram which may lead to excessive use (Gao et al., Citation2017; Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). In the present study it is hypothesized that:

H1: Social gratification in Instagram is positively associated with excessive Instagram use.

4.2. Content gratification

Content gratification is concerned with the message conveyed by the medium (Stafford et al., Citation2004). For example, information is the main content that most users are looking for online, which is the most important among the different forms of content gratification (Stafford et al., Citation2004). With the advance of Web 2.0 applications, SNSs provide abundant content for users, such as text, photos, and videos. This content enhancement allows SNSs users to interact with each other to derive value that attract their interests, and stimulates content-based gratification (Li et al., Citation2018). Recently, due to digitization, the use of photos has been changed from preserving memories to fast become more in sharing moments of users’ daily life (Lee et al., Citation2015). In Instagram, sharing photos and videos with others can be gratifying as users are allowed to scroll through other users’ profiles and view all of the photos that a particular individual has uploaded (Lee & Sin, Citation2016). This behavior of viewing photos and videos on Instagram may become a daily habit and lead to excessive use of the platform (Lee & Sin, Citation2016). Therefore, in the present study, it is hypothesized that:

H2: Content gratification in Instagram is positively associated with excessive Instagram use.

4.3. Entertainment

Studies that use UGT have broadly identified entertainment as an important factor affecting the use of a particular medium (Li et al., Citation2018). Entertainment is defined as “the pleasurable and relaxing use without a meaningful purpose, such as leisure, passing time” (Li, Guo, et al., Citation2018, p. 1233). Entertainment has been found to have a positive effect of excessive use of the internet (Islam et al., Citation2018). In particular, studies investigating SNSs have highlighted that entertainment is one of the main motivational factors in using these platforms (Alhabash et al., Citation2014; Balakrishnan & Griffiths, Citation2017). For example, Alhabash and Ma (Citation2017) found that the intensity of using Instagram and Snapchat was higher than Facebook and Twitter among university students. The study also reported that entertainment was the strongest factor in the intensity of use among the four SNS platforms. In many cases, due to the rich entertainment features on Instagram (e.g. watching videos, photos, and live streams), students only use it for passing time and leisure purposes which can be conceptualized as entertainment motivation. Kircaburun et al. (Citation2020) empirically found that entertainment and passing time were positively associated with problematic Instagram use among university students. Consequently, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Entertainment gratification is positively associated with excessive Instagram use.

4.4. Social presence

Short et al. (Citation1976) defined social presence as “the degree of salience of the other person in the interaction and the consequent salience of interpersonal relationships” (p. 65). It is operationalized in terms of how social, personal, warm, and sensitive people perceive the medium communication tools to be (Animesh et al., Citation2011). When individuals perceive a high level of social presence via their personal interactions on SNSs, they tend to be deeply involved and engaged in SNS use (Gao et al., Citation2017). Using different features on SNSs will lead to a higher feeling of social presence (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). However, the sense of social presence differs according to which platform is used. For example, Pittman and Reich (Citation2016) highlighted that image-based social media platforms (i.e. Instagram, Snapchat) offer a higher level of simulated social presence than text-based platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. Previous studies have found that social presence has a positive effect on problematic Instagram use in high school and university students (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). Based on this literature, it is hypothesized that:

H4: Social presence in Instagram is positively associated with excessive Instagram use.

4.5. Escapism

Escapism was defined by Young et al. (Citation2017) as “a behavior employed to distract oneself from real life problems” (p. 25). It is related to engaging in activities that are absorbing to the level of offering an escape from reality, pressure, and other life problems (Wu & Holsapple, Citation2014). Previous studies have affirmed that individuals engage in activities such as online gaming and social media use to escape from reality which results in problematic use and can lead to addiction in a minority of cases (Gao et al., Citation2017; Masur et al., Citation2014). For example, Alhabash et al. (Citation2014) found that escapism is a significant predictor of the Facebook use intensity. Furthermore, based on empirical evidence, Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) highlighted that escapism has a positive effect on EIU. Using different features in Instagram such as watching live streams, other people’s videos, and posting and commenting on others’ photos create the feeling of escapism (Kırcaburun & Griffiths, Citation2019). Therefore, based on the extant literature, it is hypothesized that:

H5: Escapism is positively associated with excessive Instagram use among students.

4.6. Excessive Instagram use and academic impairment

Academic achievement is considered as an important aspect of life for university students, and it is typically a crucial indicator for university students’ subsequent quality of life (Li et al., Citation2018). The use of the internet in general as a resource for education has a universal support from students, parents, educators, and institutions (Kubey et al., Citation2001). However, in general, excessive internet use is highly correlated with academic impairment among students (Islam et al., Citation2018; Kubey et al., Citation2001). As SNSs are one of the most used platforms on the internet, students’ time on these platforms has increased over the decades. This excessive use of SNSs might interfere with academic achievement and negatively affect students’ academic performance. Prior studies have provided evidence that a minority of SNS users, especially students, can become highly preoccupied or “addicted” to SNSs which directly affects their health, personal relationships, and/or academic performance (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2011). Excessive use of SNSs (e.g. Facebook, Instagram) distracts students’ concentration and causes disruptive multitasking during their academic study, which leads to students being less focused (e.g. during class or studying for exams) and which may lead to academic impairment among students. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H6: Excessive Instagram use is positively associated with students’ academic impairment

5. Methods

5.1. Participants and settings

The participants in the present study comprised students at two Malaysian universities. The students were invited via emails, universities’ Facebook pages, and students’ WhatsApp groups to participate in the study by filling out the survey. The students were asked if they used Instagram at the beginning of the survey, to make sure that all the respondents have experience with Instagram use. In addition, to increase the response rate, a printed version of the survey was also distributed to students. The total collected surveys from both online and offline were 302 respondents. A total of 17 participants were excluded from the dataset due to incomplete answers and suspicious response patterns (Hair et al., Citation2022). All participants were Malaysian university students who were daily users of Instagram (n = 285). The sample comprised 143 male students (50%), and 142 female students (50%). More than half of the respondents were aged 20–29 years (58%), followed by those who are aged 30–39 years (35%), and the remainder were aged above 40 years (7%). The majority of the respondents were undergraduate students (n = 155; 54%), followed by a master’s degree students (n = 110; 39%), while the remainder were PhD students (n = 7; 20%).

5.2. Measures

All items were adapted from established previous studies. All the items were refined according to the context of the present study in order to capture the accurate assessment of each construct. Social gratification was assessed using four items adopted from Balakrishnan and Griffiths (Citation2017) and Jahn and Kunz (Citation2012) (e.g. “I can interact with other people on Instagram”). The composite reliability (CR) of social gratification was more than 0.80, with items loadings between 0.77 and 0.90, and AVE = 0.588. Content gratification was assessed by five items adopted from Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) (e.g. “When I use Instagram, I can watch live streams”). The CR of content gratification was 0.90 and internal validity was 0.89. Entertainment was assessed by three items adopted from Li et al. (Citation2018) (e.g. “I use Instagram when I have nothing better to do”). The Cronbach’s α of entertainment was 0.88–0.90 and the AVE was 0.74–0.90. Social presence was assessed using five items adopted from Gao et al. (Citation2017) and Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) (e.g. “There is a sense of sociability in Instagram”). The CR of social presence was 0.87, items loadings were between 0.74 and 0.80, and AVE was 0.580. Escapism was assessed using five items adopted from Gao et al. (Citation2017) (e.g. “Using Instagram helps me escape from the pressures of the study”). The CR value of escapism was 0.84, items loadings were between 0.75 and 0.79, and AVE was 0.58. EIU was assessed using five items adopted from Caplan and High (Citation2006), and Zheng and Lee (Citation2016) (e.g. “I stay on Instagram longer than I initially intended”). The CR and AVE values of EIU were 0.87 and 0.69, respectively. Finally, academic impairment was assessed using five items adopted from Kubey et al. (Citation2001) and Nayak (Citation2018) (e.g. “How often has your schoolwork been hurt because of the time you spend on Instagram?”), using five-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The items loadings of academic impairment were between 0.71 and 0.73. The rest of the items were assessed using a five-point Likert Scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

5.3. Data analysis

The study applied two approaches – partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and ANN to understand the relationship between the constructs in a more comprehensive way. In order to employ the first approach of the analysis, PLS-SEM was used to assess the reliability and validity of the instrument items, as well as testing the proposed hypotheses. The reasons behind using PLS-SEM over the covariance-based SEM is that the nature of this study was exploratory rather than confirmatory, and PLSE-SEM is more appropriate compared to CB-SEM due to the higher statistical power of PLS-SEM (Hair et al., Citation2019). SEM is the dominant method for analyzing hypotheses and examining the important determinants when ANN is unable to do so (Asadi et al., Citation2019). SEM can only be used to test linear models (Tan et al., Citation2014). Therefore, artificial intelligence techniques such as ANN were used because of their capacity to test complex non-linear relations (Priyadarshinee et al., Citation2017). Because of its “black-box” nature, ANN techniques are not appropriate to examine hypotheses and test causal relationships (Liébana-Cabanillas et al., Citation2018). Consequently, the present study integrated two-stage SEM and ANN approaches to test the hypotheses as well as to identify the important predictors for EIU. SmartPLS v3.0 software was used to perform the PLS-SEM analysis.

6. Results

6.1. Measurement model assessment

The measurement model assessment was carried out by testing the reliability, and the convergent and discriminate validity of the constructs (Hair et al., Citation2022). The reliability of the measurement model was established by examining the Cronbach alphas and composite reliability (CR). shows that the values of the Cronbach alphas and CR all exceeded the recommended thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5 which confirm that the measurement model is highly reliable.

Table 1. Reliability and validity results.

Convergent validity was assessed by examining the outer loading of items, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). shows that the values of outer loadings and AVE clearly exceeded the recommended thresholds of 0.7, and 0.5, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2019), which demonstrate that the convergent validity was established.

Discriminant validity was obtained by comparing the square root of AVE of the construct with other construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2022; Leong et al., Citation2015). shows the square root of AVEs were greater than their respective coefficients of correlation. This demonstrates that discriminate validity was achieved. Furthermore, heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) was also applied as a new criterion for assessing discriminant validity. If the HTMT value between two variables close to 1, it indicates a lack of discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2016; Henseler et al., Citation2015). Henseler et al. (Citation2015) suggest a value of 0.90 for the structural models that include conceptually similar constructs. indicates that HTMT values of each construct were below 0.90.

Table 2. Discriminant validity based on Fornell–Larker criterion.

Table 3. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) results.

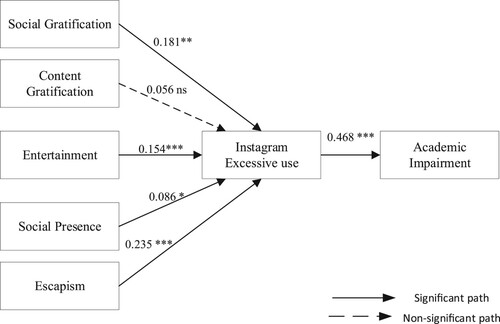

6.2. Structural model assessment

The bootstrapping technique with 5000 sub-sample (one-tailed test) was applied to estimate the path significance. The model’s explanatory power (R2) was 0.22 (indicating that the variables explained 22% of the variance in academic impairment). Furthermore, the results of the structural model assessment as shown in shows that social gratification (p = 0.033), entertainment (p = 0.008), social presence (p = 0.076), and escapism (p < 0.001) were found to have a positive significant effect on EIU, while content gratification (p = 0.192) did not have any significant effect on EIU. The results also show that EIU had a significant positive impact on students’ academic performance (p < 0.001). This indicates that students who spent more time on Instagram experienced greater academic impairment. In addition, the effect sizes (f2) were estimated. The f2 results, as shown in , show that social gratification, entertainment, social presence, and escapism all had a small effect on EIU (f2 = 0.029, 0.023, 0.020, 0.052, respectively), whereas EIU had a large effect on academic impairment (f2 = 0.30) (Hair et al., Citation2022). summarizes the results of SEM structural model analysis.

Table 4. Structural model results.

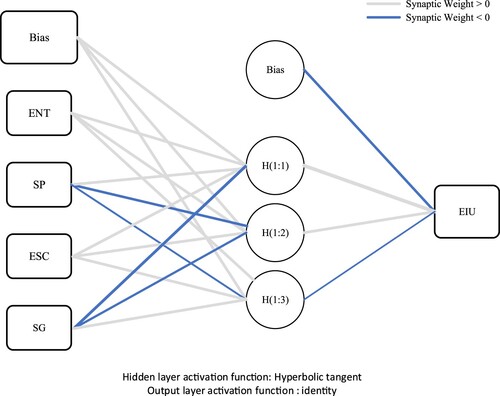

6.3. ANN analysis

Based on the results of the SEM analysis, the four important variables (social gratification, entertainment, social presence, and escapism) were utilized for ANN analysis. SPSS v.24 was used to build and analyze the ANN model. Based on the proposed model in and the results obtained from the SEM analysis, the ANN model comprised four inputs (entertainment, social presence, escapism, and social gratification) and one output (excessive Instagram use). shows the ANN model.

The ANN was confirmed by calculating the root mean square error (RMSE) in both the testing and training datasets. To avoid over-fitting, the ten-fold cross validation procedure was applied by Tan et al. (Citation2014), whereby 70% of data were used for training the neural network and the remaining 30% were used for testing the trained network (Liébana-Cabanillas et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), To test the accuracy of the proposed model, RMSE from 10 networks was employed. The average cross-validation RMSE value for testing model was 0.291082 and for training was 0.256188 (see ). Therefore, the obtained low RMSE values showed that the proposed model was very reliable and the ANN model was accurate and consistent in explaining the relationships between the predictors and EIU (i.e. the output variable) (Zabukovšek et al., Citation2019).

Table 5. RMSE for neural network model.

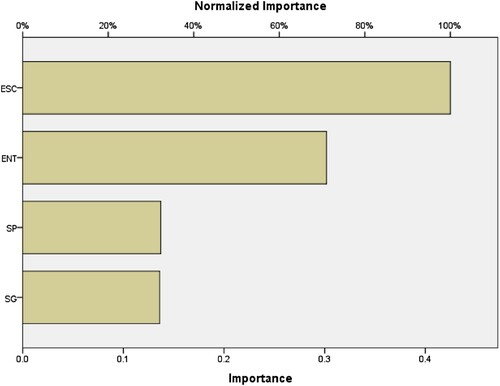

presents the summary of the sensitivity analysis (SA) for each independent variable. The importance of each predictor (input variables) was obtained through the analysis of ANN and used for the final ranking. As stated by Chong and Bai (Citation2014) “the importance of predictor measures how much the networks’ model predicted value changes for different values of predictors”. Therefore, on the basis of the normalized variable importance results ( and ), escapism was the most important construct in predicting EIU followed by entertainment, social presence, and social gratification. Compared to SEM results, the results of the SA showed similar findings in terms of the importance of independent variables (see ). Both results confirmed that escapism was the most important variable that influenced students’ excessive use of Instagram (t = 3.625, SA = 100%), followed by entrainment (t = 2.399, SA = 71.1%), then social presence (t = 1.4, SA = 32.3), and social gratification (t = 1.8, SA = 32%)

Table 6. Sensitivity analysis.

7. Discussion

7.1. Key findings

First, the results showed that social gratification was significantly associated with EIU. As expected, this result is not surprising because of the social nature of SNS platforms. Similar to other SNSs, students use Instagram to meet other people, receive social support, and share photos and videos with others. Lee, Lee, et al. (Citation2015) emphasized that Instagram users utilize photos as a way of presenting their lifestyle, personalities, and tastes with others. Therefore, actively participating in sharing daily photos and watching others’ videos gratify students leading to them spending more time on Instagram. This is consistent with that of Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) who found that problematic Instagram use was associated with excessive use of social activities such as watching live streams, commenting on others’ posts, and liking others’ photos and videos. However, the results of the present study also indicated that content gratification of Instagram was non-insignificant in relation to EIU. A possible explanation for these results is that, in the context of the Instagram environment, the main gratification for students using Instagram excessively is the social experience, rather than the message or the content of particular posts (e.g. photos or videos). Consistent with this argument, Kırcaburun and Griffiths (Citation2019) found that users on Instagram watch live streams and like and comment on other content in order to have higher feeling of social presence.

Additionally, the results showed that entertainment was significantly associated with EIU. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that entertainment is among the strongest motivational factors in why individuals use SNSs (Alhabash et al., Citation2014; Alhabash & Ma, Citation2017). This finding is also in line with that of Kircaburun et al. (Citation2020) who reported that passing time and entertainment gratifications were positively associated with the intensity of Instagram use among undergraduate students. Although this and previous research demonstrates SNS users are mainly motivated to use SNS platforms to maintain social connections and establish new relationships with others, in the present study the association between entertainment and EIU was statistically higher than that of social gratification. The same finding was reported by Alhabash et al. (Citation2014) in relation to Facebook.

Second, the results showed that the highest gratification associated with EIU in the present study was escapism. This finding is consistent with Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) who found that escapism was positively associated with students’ problematic Instagram use. This shows that students who spend more time on Instagram feel a higher sense of escapism, which leads to higher-intensity use of Instagram. The same findings have appeared in other SNS contexts. For example, Gao et al. (Citation2017) found that escapism was a significant predictor of problematic SNS use and led to addictive behavior in some cases. Because most students possess smartphones, and smartphones are devices on which a wide range of activities can be engaged in (e.g. browsing SNSs especially Instagram (Lee et al., Citation2015), gaming, watching videos), these are all the activities which can satisfy individual needs and provide an escape from daily academic stress. Consequently, it is not surprising that students tend to spend more time on Instagram because it is available 24/7 on their smartphones. This supports Wang et al.’s (Citation2015) argument that students who are more stressed are highly motivated in using their smartphone use to escape, which in some cases appears to cause problematic smartphone use. The findings in the present study lend support to this because students use Instagram to escape problems via their smartphone which can lead to excessive use which in turn affects students’ academic performance.

Third, social presence in the present study was also found to be significantly associated with EIU. This finding is in line with previous studies in the context of SNSs (e.g. Gao et al., Citation2017). Students experience social presence on SNSs which improve their online communication abilities (Lim & Richardson, Citation2016). Previous studies on social presence have also suggested that using SNSs can enhance students’ social presence via the development of the sense of community in SNS environments (Hung & Yuen, Citation2010; Schroeder et al., Citation2018). However, the findings of the present study provided a novel insight that specifically using Instagram features can lead to a higher feeling of social presence which can result in EIU and indirectly affect students’ academic activities. This finding supports the finding by Kircaburun and Griffiths (Citation2018) who found that posting photos and live streaming on Instagram were associated with a social presence among students.

Finally, the results showed that EIU was significantly associated with academic impairment among university students. This finding supports previous studies showing the negative consequences of excessive and problematic SNS use on the academic performance of students (Al-Yafi et al., Citation2018; Cao et al., Citation2018; Junco, Citation2012a; Kirschner & Karpinski, Citation2010; Paul et al., Citation2012). For example, Kirschner and Karpinski (Citation2010) found students who intensively use Facebook spend fewer hours a week studying (affecting their academic performance) compared to non-intensive Facebook users. Paul et al. (Citation2012) reported that there was a significant negative relationship between time spent on SNS platforms by students and their academic performance. Consistent with these results, Junco (Citation2012b) surveyed university students (n = 1839) and found that heavy Facebook use and text messaging negatively affected students’ academic performance as assessed by the decline in their grade point average (GPA). Furthermore, Cao et al. (Citation2018) recently found that excessive SNS use had a significant positive effect on users’ life and privacy invasion, which subsequently diminished their academic performance. This result indicates that the gratifications provided by Instagram can result in behaviors such as constantly checking others’ posts, updating status, posting photos, and watching videos. This constant access to stimuli can lead some individuals to have strong cravings to spend longer and longer time on (and responding to others) Instagram. All this unplanned time on Instagram can directly affect some students’ academic performance. This finding is also in line with Junco (Citation2015) who found that students who frequently post and update their status on Facebook have low GPAs. Furthermore, this is consistent with a recent study in the Malaysian university context. More specifically, Ponnusamy et al. (Citation2020) found that students’ recognition and social needs had a significant relationship with Instagram addiction, which in turn, which was also associated with a negative detriment to students’ academic performance. Similarly, Foroughi et al. (Citation2022), found that student’s academic performance, among other outcomes (e.g. social Anxiety and depression) was negatively associated with Instagram addiction.

7.2. Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of the present study have some theoretical and practical implications. First, on the theoretical level, the majority of previous studies applied UGT to understand the users’ SNS behavior. The present study makes an important contribution to SNS behavioral literature regarding EIU, and affirmed that EIU had a great influence on students’ academic impairment. In addition, the study is among the first to utilize UGT to examine the motivational predictors that lead to EIU. The results of the study showed that UGT appears to be a potential lens to understand what gratifies students to use Instagram excessively. The results support the hypotheses that social gratification and entertainment are positively associated with EIU. The findings also support the idea that UGT is a suitable approach to the study of SNS behavior. Moreover, the results highlight that escapism had a positive effect on EIU and appears to motivate EIU behavior above other motivations.

On the practical level, the frequent use of SNSs (especially Facebook and Instagram) among students has encouraged some scholars to highlight the impact of excessive SNS use on academic performance, and consequent detrimental academic outcomes. Understanding that students are motivated to use Instagram excessively via a combination of gratifications and other social and behavioral predictors may provide a good foundation from which universities and higher education institutions educate students about self-regulation and control as a way of avoiding excessive Instagram use (that in a small minority of cases may lead to addictive behavior), as well as maximizing the benefits of SNS use more generally. This can be achieved by launching awareness campaigns, seminars about the corrective strategies of EIU self-regulation such as using specific tools for content-control, or provide counseling to students to follow prevention strategies to manage their excessive use, for example, recognize the signs of overused time on Instagram, and count the hours spend on the platform, turn of notification to avoid the felling of FoMO.

7.3. Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, the main objective of the study was to examine the proposed model in the Malaysian university context. Therefore, to establish the generalizability of the study, other cultural differences should be considered. Future studies may consider expanding this study by collecting data from other universities outside Malaysia and test the impact of the cultural differences. Second, the model of the study tested five gratification variables. Future research may incorporate additional variables. For instance, the present study considered two social factors as antecedents for EIU. Therefore, future research may investigate the impact of other factors such as social interactivity, social interaction, and social support. Third, the present study used quantitative data to test the impact of EIU on student’s academic impairment. Therefore, because the “dark side” of social media's effect on students is still in the early stage, qualitative data may provide a deeper understanding and explore other factors in this relationship.

8. Conclusion

Students often use Instagram frequently. The present study is the first to explore the use of UGT and multiple gratifications (i.e. social gratification, content gratification, and entertainment), social presence, and escapism and their association with EIU, and the association of EIU with students’ academic impairment. The results of the study provide insights into the negative consequences of excessive Instagram use. Providing a better understanding of the negative use of SNSs, and its effect on students’ academic performance would help universities and academic institutions to face important challenges when dealing with the SNS generation in academic environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article. The authors affiliation was incorrect at the time of acceptance and has since been corrected.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maslin Masrom

Maslin Masrom is an Associate Professor at Razak Faculty of Technology and Informatics, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Kuala Lumpur. She teaches Information Technology Strategy, Management Information Systems, ICT Ethics and Society, Advanced Decision Modelling, Knowledge Management and Technology, and Research Methodology. She has published many technical papers in journals, books and conferences. Her main research interests are in IT/IS Management, Online Social Networking, Women and Technologies, Cloud Computing in Healthcare System, Knowledge Management, Information Security, Ethics in Computing, Operations Research/Decision Modelling, and Structural Equation Modelling.

Abdelsalam Busalim

Abdelsalam Busalim ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor in Digital Business at DCU Business School. He received his PhD in Information systems from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. His research focuses on social commerce, social media, customer behavior analytics, and data analytics. He has published several papers in peer-review journals such as Computers and Education, International Journal of Information Management, Journal services marketing. Currently, he is working on multiple research projects related to; consumer behavior in sustainable fashion, social commerce engagement design features, social commerce in tourism services.

Mark D. Griffiths

Mark D. Griffiths is a Chartered Psychologist and Director of the International Gaming Research Unit. He mostly teaches on areas related to his research interests on various undergraduate and postgraduate Psychology programmes. He is internationally known for his work into gambling and gaming addictions. He has won 24 national and/or international prizes for his research and has published over 1200 refereed research papers, six books, over 160 book chapters, and over 1500 other articles.

Shahla Asadi

Shala Asadi is a Senior lecturer at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. She received his PhD in Information systems from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Her research focuses on cloud Computing, green IT, Institutional Repository, Big Data, Health Information Systems. Her research published in journal peer-review journals Resources, Conservation and Recycling, International Journal of Fuzzy Systems, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services and Journal of Cleaner Production.

Raihana Mohd Ali

Raihana Mohd Ali is a Senior Lecturer at Razak Faculty of Technology and Informatics, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. She received her PhD from Curtin University of Technology, Perth in 2013. Her main research interest focuses on tax compliance and taxation. When given a chance to be part of the team in delivering engineering business management academic programs in her faculty, Raihana is inspired to explore new areas of research interest in the engineering business management.

References

- Ainin, S., Naqshbandi, M. M., Moghavvemi, S., & Jaafar, N. I. (2015). Facebook usage, socialization and academic performance. Computers & Education, 83, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.018

- Alhabash, S., Chiang, Y. H., & Huang, K. (2014). MAM & U&G in Taiwan: Differences in the uses and gratifications of Facebook as a function of motivational reactivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.033

- Alhabash, S., & Ma, M. (2017). A tale of four platforms: Motivations and uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among college students. Social Media + Society, 3(1), 205630511769154. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691544

- Al-Jabri, I. M., Sohail, M. S., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2015). Understanding the usage of global social networking sites by Arabs through the lens of uses and gratifications theory. Journal of Service Management, 26(4), 662–680. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-01-2015-0037

- Alwagait, E., Shahzad, B., & Alim, S. (2017). Impact of social media usage on students academic performance in Terengganu, Malaysia. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 51, 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.028

- Al-Yafi, K., El-Masri, M., & Tsai, R. (2018). The effects of using social network sites on academic performance: The case of Qatar. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(3), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2017-0118

- Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

- Animesh, A., Pinsonneault, A., & Sung-Byung Yang, W. O. (2011). An odyssey into virtual worlds: Exploring the impacts of technological and spatial environments on intention to purchase virtual products. MIS Quarterly, 35(3), 789. https://doi.org/10.2307/23042809

- Asadi, S., Abdullah, R., Safaei, M., & Nazir, S. (2019). An integrated SEM-neural network approach for predicting determinants of adoption of wearable healthcare devices. Mobile Information Systems, 2019, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8026042

- Balakrishnan, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube ? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 364–377. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.058

- Balta, S., Emirtekin, E., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism, trait fear of missing out, and phubbing: The mediating role of state fear of missing out and problematic Instagram use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9959-8

- BBC. (2018). How much is “too much time” on social media?, 15 March 2021. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180118-how-much-is-too-much-time-on-social-media

- Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2008). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

- Cao, X., Masood, A., Luqman, A., & Ali, A. (2018). Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: Antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.023

- Caplan, S. E., & High, A. C. (2006). Beyond excessive use: The interaction between cognitive and behavioral symptoms of problematic internet use. Communication Research Reports, 23(4), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090600962516

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2017). Antecedents of consumer intention to follow and recommend an Instagram account. Online Information Review, 41(7), 1046–1063. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-09-2016-0253

- Chang, C.-M. (2018). Understanding social networking sites continuance. Online Information Review, 42(6), 989–1006. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2017-0088

- Chong, A. Y. L., & Bai, R. (2014). Predicting open IOS adoption in SMEs: An integrated SEM-neural network approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(1), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2013.07.023

- Donnelly, E. (2017). Depression among users of social networking sites (SNSs): The role of SNS addiction and increased usage. Journal of Addiction and Preventive Medicine, 2(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.19104/japm.2016.107

- Ershad, Z. S., & Aghajani, T. (2017). Prediction of Instagram social network addiction based on the personality, alexithymia and attachment styles. Journal of Sociological Studies of Youth, 8(26), 21–34. https://ssyj.babol.iau.ir/article_533425.html

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Foroughi, B., Griffiths, M. D., Iranmanesh, M., & Salamzadeh, Y. (2021). Associations between Instagram addiction, academic performance, social anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00510-5

- Foroughi, B., Griffiths, M. D., Iranmanesh, M., & Salamzadeh, Y. (2022). Associations between Instagram addiction, academic performance, social anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2221–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00510-5

- Gao, W., Liu, Z., & Li, J. (2017). How does social presence influence SNS addiction? A belongingness theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.002

- Giunchiglia, F., Zeni, M., Gobbi, E., Bignotti, E., & Bison, I. (2018). Mobile social media usage and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.041

- Glazzard, J., & Stones, S. (2019). Social media and young people’s mental health. Selected Topics in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7.

- Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

- Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction. In K. Rosenberg & L. Feder (Eds.), Behavioral addictions: Criteria, evidence and treatment (pp. 119–141). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hamade, S. N. (2013). Perception and use of social networking sites among university students. Library Review, 62(6/7), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/LR-12-2012-0131

- Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316660340

- Helou, A. M. (2014). The influence of social networking sites on students’ academic performance in Malaysia. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies, 5(2), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.7903/ijecs.1114

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hung, H. T., & Yuen, S. C. Y. (2010). Educational use of social networking technology in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(6), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.507307

- Idris, R. A. E., & Hasan, F. A. S. (2019). The impact of social media applications on students performance in private universities in Malaysia: Iukl case study. Global Scientific Journal, 7(12), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.11216/gsj.2019.12.32089

- Islam, S., Malik, M. I., Hussain, S., Thursamy, R., Shujahat, M., & Sajjad, M. (2018). Motives of excessive internet use and its impact on the academic performance of business students in Pakistan. Journal of Substance Use, 23(3), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2017.1388857

- Jahn, B., & Kunz, W. (2012). How to transform consumers into fans of your brand. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211248444

- Junco, R. (2012a). In-class multitasking and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2236–2243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.031

- Junco, R. (2012b). Too much face and not enough books: The relationship between multiple indices of Facebook use and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.026

- Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook use, and academic performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001

- Junco, R., Heiberger, G., & Loken, E. (2011). The effect of Twitter on college student engagement and grades. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00387.x

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 14(3), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.1086/268109

- Kim, D. H., Seely, N. K., & Jung, J. H. (2017). Do you prefer, Pinterest or Instagram? The role of image-sharing SNSs and self-monitoring in enhancing ad effectiveness. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.022

- Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the big five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6

- Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.024

- Kitsantas, A., Dabbagh, N., Chirinos, D. S., & Fake, H. (2016). College students’ perceptions of positive and negative effects of social networking. In T. Issa, P. Isaias, & P. Kommers (Eds.), Social networking and education (pp. 225–238). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17716-8_14

- Kırcaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Problematic Instagram use: The role of perceived feeling of presence and escapism. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(4), 909–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9895-7

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Saripanidis, I. (2017). A lifestyle exposure perspective of victimization through Facebook among university students. Do individual differences matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.036

- Kubey, R. W., Lavin, M. J., & Barrows, J. R. (2001). Internet use and collegiate academic performance decrements: Early findings. Journal of Communication, 51(2), 366–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02885.x

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction – a review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8093528

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

- Lee, C. S., Abu Bakar, N. A. B., Muhammad Dahri, R. B., & Sin, S.-C. J. (2015). Instagram this! Sharing photos on Instagram. In R. B. Allen, J. Hunter, & M. L. Zeng (Eds.), Digital libraries: Providing quality information (pp. 132–141). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27974-9_13.

- Lee, C. S., & Sin, S.-C. J. (2016). Why do people view photographs on Instagram? International Conference on Asian Digital Libraries (pp. 339–350). (7-9/12/ 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49304-6_38.

- Lee, E., Lee, J.-A., Moon, J. H., & Sung, Y. (2015). Pictures speak louder than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(9), 552–556. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0157

- Leong, L.-Y., Hew, T.-S., Lee, V.-H., & Ooi, K.-B. (2015). An SEM–artificial-neural-network analysis of the relationships between SERVPERF, customer satisfaction and loyalty among low-cost and full-service airline. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(19), 6620–6634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2015.04.043

- Li, J., Han, X., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018). How social support influences university students’ academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.016

- Li, Q., Guo, X., Bai, X., & Xu, W. (2018). Investigating microblogging addiction tendency through the lens of uses and gratifications theory. Internet Research, 28(5), 1228–1252. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-03-2017-0092

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Marinković, V., & Kalinić, Z. (2017). A SEM-neural network approach for predicting antecedents of m-commerce acceptance. International Journal of Information Management, 37(2), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.10.008

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Marinkovic, V., Ramos de Luna, I., & Kalinic, Z. (2018). Predicting the determinants of mobile payment acceptance: A hybrid SEM-neural network approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 129, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.12.015

- Lim, J., & Richardson, J. C. (2016). Exploring the effects of students’ social networking experience on social presence and perceptions of using SNSs for educational purposes. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.12.001

- Masur, P. K., Reinecke, L., Ziegele, M., & Quiring, O. (2014). The interplay of intrinsic need satisfaction and Facebook specific motives in explaining addictive behavior on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 376–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.047

- Mazman, S. G., & Usluel, Y. K. (2010). Modeling educational usage of Facebook. Computers and Education, 55(2), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.008

- Mirabolghasemi, M., Iahad, N. A., & Rahim, N. Z. A. (2016). Students’ perception towards the potential and barriers of social network sites in higher education (pp. 41–49). Social Networking and Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17716-8_3

- Nayak, J. K. (2018). Relationship among smartphone usage, addiction, academic performance and the moderating role of gender: A study of higher education students in India. Computers & Education, 123, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.007

- Pahlevan Sharif, S., & Yeoh, K. K. (2018). Excessive social networking sites use and online compulsive buying in young adults: The mediating role of money attitude. Young Consumers, 19(3), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2017-00743

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2117–2127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.016

- Phua, J., Jin, S. V., & Kim, J. (. (2017). Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.041

- Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084

- Ponnusamy, S., Iranmanesh, M., Foroughi, B., & Hyun, S. S. (2020). Drivers and outcomes of Instagram addiction: Psychological well-being as moderator. Computers in Human Behavior, 107(February), 106294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106294

- Priyadarshinee, P., Raut, R. D., Jha, M. K., & Gardas, B. B. (2017). Understanding and predicting the determinants of cloud computing adoption: A two staged hybrid SEM - neural networks approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.027

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., Dehaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

- Ridgway, J. L., & Clayton, R. B. (2016). Instagram unfiltered: Exploring associations of body image satisfaction, Instagram #selfie posting, and negative romantic relationship outcomes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0433

- Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Aznar-Díaz, I., Marín-Marín, J. A., Soler-Costa, R., & Rodríguez-Jiménez, C. (2020). Impact of problematic smartphone use and Instagram use intensity on self-esteem with university students from physical education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124336

- Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2020). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat use disorders mediate that association? Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106487

- Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., & Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016

- Sanz-Blas, S., Buzova, D., & Miquel-Romero, M. J. (2019). From Instagram overuse to instastress and emotional fatigue: The mediation of addiction. Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC, 23(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-12-2018-0059

- Schroeder, A., Minocha, S., & Schneider, C. (2018). Social software in higher education: The diversity of applications and their contributions to students’ learning experiences. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 26(1), 548–564. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02625

- Shane-Simpson, C., Manago, A., Gaggi, N., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2018). Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.041

- Shaw, M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Internet addiction. CNS Drugs, 22(5), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200822050-00001

- Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. Wiley.

- Stafford, T. F., & Gillenson, M. L. (2004). Motivations for mobile devices: Uses and gratifications for M-commerce. Proceedings of the Third Annual Workshop on HCI Research in MIS, Washington, D.C., April 24 - 29, 2004, (pp.70–74). HCI.

- Stafford, T. F., Stafford, M. R., & Schkade, L. L. (2004). Determining uses and gratifications for the internet. Decision Sciences, 35(2), 259–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.00117315.2004.02524.x

- Tan, G. W. H., Ooi, K. B., Leong, L. Y., & Lin, B. (2014). Predicting the drivers of behavioral intention to use mobile learning: A hybrid SEM-neural networks approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.052

- Tower, M., Latimer, S., & Hewitt, J. (2014). Social networking as a learning tool: Nursing students’ perception of efficacy. Nurse Education Today, 34(6), 1012–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.11.006

- Turel, O., Serenko, A., & Giles, P. (2011). Integrating technology addiction and use: An empirical investigation of online auction users. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 35(4), 1043–1061. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409972

- Wang, J. L., Wang, H. Z., Gaskin, J., & Wang, L. H. (2015). The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.005

- Wu, J., & Holsapple, C. (2014). Imaginal and emotional experiences in pleasure-oriented IT usage: A hedonic consumption perspective. Information and Management, 51(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.09.003

- Young, N. L., Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Howard, C. J. (2017). Passive Facebook use, Facebook addiction, and associations with escapism: An experimental vignette study. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.039

- Yusop, F. D., & Sumari, M. (2013). The use of social media technologies among Malaysian Youth. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 1204–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.448

- Zabukovšek, S., Kalinic, S., Bobek, Z., & & Tominc, S. (2019). SEM–ANN based research of factors’ impact on extended use of ERP systems. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 27(3), 703–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-018-0592-1

- Zheng, X., & Lee, M. K. O. (2016). Excessive use of mobile social networking sites: Negative consequences on individuals. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.011