Abstract

Objective: In this study, we evaluate the efficacy of outpatient individual cognitive behavioral therapy for young adults (CBT-YA) and combined family/individual therapy for young adults (FT-YA) for anorexia nervosa (AN). Method: Participants (aged 17–24 years) with AN in Sweden were recruited and assigned to 18 months of CBT-YA or FT-YA. Treatment efficacy was assessed primarily using BMI, presence of diagnosis, and degree of eating-related psychopathology at post-treatment and follow-up. Secondary outcomes included depression and general psychological psychopathology. The trial was registered at http://www.isrctn.com/, ISRCTN (25181390). Results: Seventy-eight participants were randomized, and seventy-four of them received allocated treatment and provided complete data. Clinical outcomes from within groups resulted in significant improvements for both groups. BMI increased from baseline (CBT-YA 16.49; FT-YA 16.54) to post-treatment (CBT-YA 19.61; FT-YA 19.33) with high effect sizes. The rate of weight restoration was 64.9% in the CBT-YA group and 83.8% in the FT-YA group. The rate of recovery was 76% in both groups at post-treatment, and at follow-up, 89% and 81% had recovered in the CBT-YA and FT-YA groups respectively. Conclusions: Outpatient CBT-YA and FT-YA appear to be of benefit to young adults with AN in terms of weight restoration and reduced eating disorder and general psychopathology.

目的:本研究評估門診治療中針對有神經性厭食症(AN)診斷的年輕成人進行個別認知行為治療(CBT-YA)及結合家族/個別治療(FT-YA)。方法:研究招募在瑞士被診斷神經性厭食症的患者為研究參與者(年齡 17-24 歲),分派到為期 18 個月的 CBT-YA 或 FT-YA 的療程。研究蒐集治療前後與追蹤期之 BMI、診斷存在與否、以及飲食相關心理病理症狀等作為主要治療功效評估。次級成效指標包含憂鬱狀態與一般心理病理學症狀。本研究在 http://www.isrctn.com/ 系統註冊,編號為 <http://www.isrctn.com/%E7%B3%BB%E7%B5%B1%E8%A8%BB%E5%86%8A> ISRCTN(25181390)。結果:78 名研究參與者被隨機指派,但僅有 74 名接受指定治療且提供完整資料。兩組組內比較之臨床成效皆顯示顯著的進展。BMI 值自研究基準線(CBT-YA 16.49; FT-YA 16.54)起增加,至治療結束後(CBT-YA 19.61; FT-YA 19.33)有高效應量。體重恢復程度在 CBT-YA 組為 64.9%、在 FT-YA 組則為 83.8%。兩組在治療後之復原程度皆為 76%、而在追蹤期則分別為 89% (CBT-YA)和 81% (FT-YA)。結論:門診治療中對患有神經性厭食症的年輕成人進行個別認知行為治療及結合家族/個別治療均有助於案主恢復體重、減少飲食疾患與一般心理病理症狀。

Objetivo: Neste estudo avalia-se a eficácia da terapia cognitivo-comportamental para jovens adultos (TCC-JA) em ambulatório, combinada com terapia Familiar/individual para jovens adultos (TF-JA) com anorexia nervosa (AN). Método: os participantes (com idade entre os 17 e os 24 anos) com AN na Suécia foram recrutados e alocados para 18 meses de TCC-JA ou TF-JA. A eficácia do tratamento foi avaliada principalmente utilizando o BMI, presença de diagnóstico, e grau de patologia alimentar após o tratamento e em follow-up. Os resultados secundários incluíram depressão e psicopatologia psicológica geral. O ensaio foi registado em http://www.isrctn.com/, ISRCTN (25181390). Resultados: setenta e oito participantes foram randomizados, setenta e quatro receberam um tratamento e forneceram dados completos. Resultados clínicos dentro dos grupos resultaram em melhorias significativas para ambos os grupos. BMI aumentou desde a linha de base (TCC-JA 16.49; TF-JA 16.54) para o pós-tratamento (TCC-JA 19.61; TF-JA 19.33) com tamanhos de efeito altos. A taxa de restauração de peso foi de 64,9% no grupo TCC-JA e 83,8% no grupo TF-JA. A taxa de recuperação foi de 76% nos dois grupos, no pós-tratamento e no follow-up, 89% e 81% tinham recuperado nos grupos TCC-JA e TF-JA, respetivamente. Conclusão: TCC-JA e TF-JA em ambulatório, aparentam ser de benefício para jovens adultos com AN, em termos de restauração do peso, redução de perturbação alimentar e de psicopatologia geral.

Obiettivo: in questo studio, abbiamo valutato l’efficacia di una terapia cognitivo comportamentale individuale ambulatoriale per giovani adulti (CBTYA) e una terapia individuale/familiare combinata per giovani adulti (FT-YA) per anoressia nervosa (AN). Metodo: sono stati reclutati partecipanti (età tra 17 e 24 anni) con AN in Svezia e assegnati a 18 mesi di CBTYA o di FT-YA. L’efficacia del trattamento è stata valutata utilizzando principalmente il BMI, presenza di diagnosi e grado di psicopatologia legata alla nutrizione post-trattamento e al follow-up. Esiti secondari hanno incluso depressione e psicopatologia psicologica generale. Il trial è stato registrato al sito http://www.isrctn.com/, ISRCTN (25181390). Risultati: settantotto partecipanti sono stati randomizzati e settantaquattro di loro sono stati assegnati a un trattamento e fornito dati completi. Gli esiti clinici all'interno dei gruppi hanno mostrato miglioramenti significativi per entrambi i gruppi. Il BMI è aumentato dalla baseline (CBT-YA 16.49; FT-YA 16.54) al post-trattamento (CBT-YA 19.61; FT-YA 19.33) con dimensioni del’effetto grandi. Il tasso di ripristino del peso è stato del 64,9% nel gruppo CBT-YA e dell'83,8% nel gruppo FT-YA. Il tasso di recupero è stato del 76% in entrambi i gruppi al post-trattamento e al follow-up, l'89% e l'81% si era ripreso rispettivamente nei gruppi CBT-YA e FT-YA. Conclusioni: CBTYA e FT-YA ambulatoriale sembrano essere di beneficio ai giovani adulti con AN in termini di ripristino del peso e riduzione dei disturbi alimentari e psicopatologia generale

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: Young adult patients with AN can benefit both physically (BMI) and psychologically from outpatient psychotherapy. More than 80% of patients do not fulfill the criteria for an eating disorder diagnosis at follow-up. Combined Family/Individual therapy and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy both seem promising for a young adult AN population.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized by significant negative effects, consisting of physical and psychological impairments (Smink, van Hoeken, & Hoek, Citation2012; Treasure, Claudino, & Zucker, Citation2010). While the incidence of AN has stabilized over the years, an increase of cases has been observed within the high-risk group (15–17 years of age) (Micali, Hagberg, Petersen, & Treasure, Citation2013; Smink et al., Citation2012). The disorder is difficult to treat, and although many individuals with AN recover in the long term, the course of AN can become prolonged leading to an elevated risk of premature death (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, & Nielsen, Citation2011; Keel & Brown, Citation2010; Steinhausen, Citation2002; Stice, Marti, & Rohde, Citation2013; Watson & Bulik, Citation2013) and substantially increased costs due to inpatient treatment (Stuhldreher et al., Citation2012). Recent research shows promising results with modest effects for weight recovery and symptom reduction for behavioral treatments for adult AN patients (Zipfel, Giel, Bulik, Hay, & Schmidt, Citation2015).

When the present study was initiated, trials including family interventions and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for adults/young adults with AN were scarce. We identified one study that compared family therapy for adult patients with AN with individual cognitive analytic therapy and general psychodynamic therapy. These treatments were found to be superior in an outpatient setting (Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure, & Dodge, Citation2001). Another small study compared generic CBT and a specific behavioral family therapy for young adult patients with AN (Ball & Mitchell, Citation2004). With a small sample of 25 patients and a dropout rate of 28%, only 9 participants remained in each treatment group at the end of treatment. The majority of patients achieved full recovery, with no significant difference between the groups.

Although family interventions were developed for children and adolescents, the reasons for using this form of treatment for young adult patients with AN are based on the clinical experience of treating this patient population. From a clinical point of view, many young adult patients still live with their parents. These young adults have not developed relationship skills and often rely on their parents’ care and engagement. It is obvious that they need parental support during treatment and that the family needs to reorganize itself around the patient in order not to perpetuate the disorder.

The evidence base for treating adults continues to be considered limited (Watson & Bulik, Citation2013) but has improved significantly (Brockmeyer, Friederich, & Schmidt, Citation2018; Zeeck et al., Citation2018). However, no specific trials have been conducted for evaluating young adults only. Therefore, evidence does not specify any superior treatment with sufficient empirical support (Brockmeyer et al., Citation2018; Hay, Claudino, Touyz, & Abd Elbaky, Citation2015; Watson & Bulik, Citation2013; Zipfel et al., Citation2015). Even though the present trial was established more than ten years ago, recent recommendations have encouraged research on adult patients with AN, with a focus on comparisons between CBT and family therapy (Dalle Grave, El Ghoch, Sartirana, & Calugi, Citation2016; Fisher, Hetrick, & Rushford, Citation2010; Hay et al., Citation2015), thereby supporting the importance of reporting the results from the present trial.

Against this background, the main aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of outpatient CBT for young adults (CBT-YA) and family therapy for young adults (FT-YA). We hypothesized that both treatments would be effective primarily in terms of an increase in BMI and a reduction of eating disorder (ED) psychopathology, with a decrease in general psychological pathology as the secondary outcome. In addition to the primary aim, we used exploratory approach testing to determine potential differences between groups.

Methods

Participant Characteristics

The participants were recruited between 2005 and 2011. Applicants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: female gender, between 17 and 24 years of age, with an AN diagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (APA, Citation2000). The maximum BMI level for being included in the study was 17.5, and no lower limit was applied. Exclusion was based on the following criteria: critical medical status in need of acute care, current suicidal thoughts and/or suicidal behavior, and/or current alcohol or substance abuse. Participants with on-going psychotherapeutic or psychotropic treatments were not included because the aim was to evaluate the effect of the specific psychotherapy and to reduce the risk of weight gain as a side effect of medication. If participants 18 years or older did not accept their parents’ participation, or if parents themselves chose not to take part, the participant/family was not accepted into the study. We included patients who would turn 18 years of age within the first year of treatment.

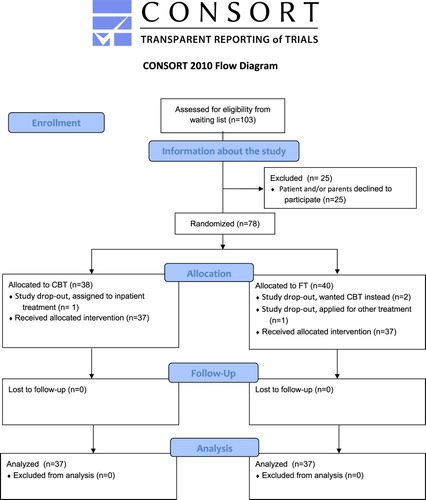

The CONSORT diagram in displays the participant flow through different stages of the trial. Four participants requested to be fully excluded from the study after the random allocation process and were considered post-randomization dropouts. The remaining 74 participants, with a mean age of 18.9 (SD = 1.95), 37 in each group, were assessed on all three occasions.

Three of the 74 participants were at the time of post-assessment and/or follow-up (FU) abroad and were therefor assessed by telephone (one in the CBT-YA group at post-assessment and follow-up (FU) and two in the FT-YA group at FU), at post-assessment, and FU. Their self-reported weights were registered as missing.

There were no significant differences between the groups regarding demographic and clinical baseline characteristics (i.e., age, BMI, duration of AN, civil status, or diagnostic and eating-related psychopathology) as seen in . For the family sessions, both parents were invited to participate regardless of whether they were divorced, but family sessions could be conducted with only one parent. When treatment began, both parents participated for 26 of the participants in the FT-YA group of whom seven were divorced; eight included only their mothers, of whom five were divorced and one was widowed; and three had only the father involved, of whom two were divorced. In the CBT-YA group, 29 participants had both parents involved, of whom six were divorced; seven included only their mothers of whom three were divorced; and one divorced father participated. From pre- to post assessment, nine participants moved away from home in the FT-YA group and eleven in the CBT-YA group. In addition eight FT-YA and seven CBT-YA participants moved away from home during the 18-month follow-up.

Table I. Baseline characteristics. Mean (SD) or number of patients (%).

Sampling Procedure

Recruited participants received outpatient treatment at the Anorexia and Bulimia Unit, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. All recruits had been thoroughly examined and undergone a diagnostic assessment and a medical examination by an experienced psychiatrist.

Those who agreed to participate were thoroughly assessed at baseline using a semi-structured diagnostic interview for EDs and self-report measures. Parents were also assessed using self-reports. In the event of a serious medical condition during the treatment, the participant would be admitted to inpatient treatment but remain in the study. If the participant was symptom-free and reached a healthy BMI before the maximum treatment length, a mutual agreement to end the treatment could be reached between the therapists and the participant/parents.

Participants were randomly assigned to CBT-YA or FT-YA. The SPSS 15.0 random number generator was used to determine the order of treatments and these were distributed in sealed envelopes. The four therapists were assigned to treatments in a fixed order, controlling for possible therapist effects. In CBT-YA, one therapist was assigned for each participant, and in FT-YA, two therapists were assigned for each participant. However, the therapist effect was not examined in this study. After completing the assessment, participants and their families were assigned to a treatment and therapist/therapists. The time and date for the initial session were set after the assessment.

Sample Size

When this trial was created, the designs of superiority had not been well incorporated into the research field of ED. The designs of superiority test the null hypothesis of treatment A as being better than treatment B; non-inferiority tests the null hypothesis of treatment A as being worse than treatment B; and equivalence tests the null hypothesis of treatment A as neither being better nor worse than treatment B (Walker & Nowacki, Citation2011). As a result, this study was not powered for any of these designs. No a priori power calculation was performed before the trial was established. The initial aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of these treatments in an outpatient setting without expecting any differences between groups. The procedure of randomization was used to establish adequate and equal preconditions for both study groups.

No significant difference was found between groups at post-treatment or FU. Due to the lack of a priori power calculations, we, therefore, performed a statistical post-hoc power analysis to test for achieved power of differences between groups based on sample size, alpha, and the true effect size obtained from the results in the present trial. The software used was G*Power 3.1. The effect size in this study between the groups at FU was 0.3, which is considered a small to medium effect using Cohen’s (Citation1988) criteria. With an alpha of 0.05 the true power was 25%.

To find a significant difference between groups based of effect size, alpha, and a power of 80%, the G*Power 3.1 software calculated a required sample size of 128 in total and 64 participants in each group. Correcting for a drop-out rate of 30%, the sufficient number was 166 participants.

Assessment and Outcome Measures

The trial used a battery of instruments to evaluate treatment outcome. For the full list of instruments, please visit the clinical trial registry at http://www.isrctn.com/, (ISRCTN 25181390). For the evaluation of treatment outcome in this study, we used three different sources of information: objective measurements, experts’ ratings, and self-report measures. These provide an overall cumulative clinical picture of the severity and consistency. Pre-treatment assessment used several instruments to measure a variety of clinical characteristics and different symptoms and/or difficulties. Our primary outcomes reflect key features and behaviors associated with AN: BMI (kg/m2), DSM-IV ED diagnosis, (APA, Citation2000) and an ED Diagnostic Index (ED Index) constructed by combining three questions from the Ratings of Anorexia and Bulimia Revised (RAB-R) (Nevonen, Broberg, Clinton, & Norring, Citation2003) expert interview. RAB-R is used as the expert rating and is a semi-structured interview assessing a wide range of ED and related psychopathology with graded responses and background variables, which generate an operational DSM-IV ED diagnosis. Each question is graded based on the participant’s answer to the interviewer. In this case, the assessor, described under “recruitment process and randomization,” graded the interview. The grading of each question is described below.

RAB-R has been shown to discriminate between healthy controls and ED participants and has satisfactory internal consistency for most subscales (alpha > 0.70), except for two of the subscales regarding anorexic eating behavior and relationships (alpha 0.42 and 0.63). Inter-rater reliability ranged between 0.65–0.87, and the test-retest, criterion validity, and concurrent validity were satisfactory (Nevonen et al., Citation2003).

For this study, we used the following questions: “Do you limit the amount of food you eat (e.g., by eating small portions or excluding meals)? If so, is this to control your weight? How often and to what extent do you limit your eating?” The response was graded on a 0–3 scale with the following answers: 0 = Does not limit eating; if eating is limited, this occurs only on very special occasions, 1 = Sometimes limits eating (e.g., isolated days of dieting or fasting), 2 = Often limits eating (e.g., periodically engages in dieting or fasting), 3 = Constantly limits eating (e.g., very conscientiously engages in strict dieting or fasting over long periods of time). Another question asked, “How important is the patient’s body shape for self-esteem?” The answer was graded on a 0–2 scale; 0 = Within normal limits, 1 = Moderately disturbed, and 2 = Pathological/ extremely disturbed. The last question was based on the item “Rating of weight phobia.” The response was graded from 0–4; 0 = No weight phobia, 1 = Weight phobic tendencies, 2 = Sub-clinical weight phobia, 3 = Clear weight phobia, and 4 = Extreme weight phobia. These questions captured the core features of an AN diagnosis (i.e., restrictive eating, preoccupation with weight and/or body image, pathological fear of fatness) during the past three months. Questions were expert rated according to the responses from the participants.

To measure ED-specific and general psychopathology, the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) (Garner, Citation2004; Nyman-Carlsson, Engstrom, Norring, & Nevonen, Citation2015) was used. The EDI-3 is a 91-item self-report questionnaire divided into three ED subscales, nine psychological subscales, and six composite scales consisting of combinations of subscales. The EDI-3 aims to measure ED symptoms and general psychopathology commonly associated with EDs. For the study, we used two composite scales: The Eating Disorder Risk Composite (EDRC) and The General Psychological Maladjustment Composite (GPMC). The psychometric properties of the EDI-3 have been established in several studies, including both international and Nordic samples. The internal consistency has, in most cases, been above 0.80 for all age ranges; test-retest coefficients were shown to be excellent; and factor structure was acceptable for the 12 subscales with an acceptable convergent validity (Clausen, Rosenvinge, Friborg, & Rokkedal, Citation2011; Garner, Citation2004; Nyman-Carlsson et al., Citation2015).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, Citation1988) was also used to measure depressive symptoms. The BDI has been extensively tested for its psychometric properties and has shown good internal consistency (>0.90) and the ability to discriminate between patients with and without depression. Moreover, its concurrent, content, and structural validity have been confirmed (Wang & Gorenstein, Citation2013). Together, the EDI-3 and the BDI represent the secondary outcomes. Social and demographical data were collected with a specific self-report form.

Post-assessments of treatment outcomes were conducted 18 months after starting treatment, using the same battery of instruments as the pre-assessment, with the addition of a FU version of the semi-structured ED interview (RAB-R) and a self-report evaluation of the patient experience of satisfaction. To evaluate relative acceptability, ratings of satisfaction were measured using the Treatment Satisfaction Scale (TSS) (α = 0.86) (|Clinton, Björck, Sohlberg, & Norring, Citation2004). This instrument consists of five items, each using a three-point scale. The scale focuses on reception at the unit, suitability of the treatment program, experienced understanding of individual problems, trust in treatment staff, and level of agreement on treatment goals.

All FUs were performed 18 months after post-assessment using the same measures and instruments. The participant/parents were reimbursed with two movie tickets for participating in the FU.

Research Design

The study used a single-center randomized controlled trial (RCT) that evaluated the efficacy of two forms of outpatient psychotherapy for young adult women with AN. Participants were recruited between 2005 and 2011 and received up to 60 one-hour sessions of CBT-YA or up to 40 one-and-a-half-hour sessions of FT-YA over 18 months. Both treatment manuals were adapted to offer the same amount of maximum treatment hours (CBT-YA: 60 min for 60 sessions = 60 hr; FT-YA = 90 min for 40 sessions/60 min = 60 hr). Men were not included due to their low incidence (less than sufficient for meaningful statistical analysis).

Participants were assessed pre-treatment, and outcome measures examined the effects of the treatments 18 months after the initial treatment. FU was conducted after an additional 18 months. Recruitment and all assessments were conducted by the research leader and principal investigator who is an experienced psychotherapist licensed by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and an associate professor specializing in EDs. He was responsible for the recruitment and met with the participants and their families to inform them about the study. He has many years’ experience working with people with EDs and is highly familiar with the diagnostics of AN. Although he was not involved in the treatments, blindness to treatment allocation could not be ensured during the assessments and interviews.

Five female therapists conducted the treatment. All were Caucasian, of Swedish nationality, and between 45–65 years of age. They were all licensed psychotherapists authorized by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. During the trial, one therapist retired and had to be replaced. All therapists had significant experience treating ED patients with generic cognitive behavioral therapy and family-based therapy. Each therapist (A-E) had at least 14 years of experience working with young adults at the unit. Two of the therapists (i.e., A and E) had a psychodynamic orientation, and the other three therapists (B, C, E) were involved in family therapy. Each therapist had additional education in generic CBT. Therapist A was assigned 11 CBT patients and had a total of 21 FT therapies; six were assigned to B; seven to C; and eight to D.

Therapist B had 16 CBT patients and 16 FT (together with A = 6, D = 7, and E = 3). Therapist C treated three CBT patients and 13 FT (together with A = 7, D = 2, and E = 4). Therapist D treated four CBT patients and 17 FT (together with A = 8, B = 7, and C = 2). Therapist D treated three CBT patients and seven FT patients (in collaboration with B = 3 and C = 4). The manuals, specifically produced for the trial, were developed in cooperation with the therapists and the research leader.

All therapists were thoroughly familiar with the treatment components and the manuals, and specific training was covered prior to the trial. The psychotherapists met for peer-supervision to discuss both adherence to the manuals and specific clinical cases every two weeks. To preserve the naturalistic setting of the trial, the head of the clinical unit and the research team met monthly to ensure stability and continuity of the trial.

The ethics committee of Gothenburg approved the study (Dnr: 123-05), and the trial was registered at http://www.isrctn.com/, number ISRCTN (25181390). To participate, informed consent was required from all participants and written consent from participants and parents of participants under 18, the legal age of consent.

Treatment Manuals

The principal investigator, in cooperation with the psychotherapists who conducted both treatments created and developed both of the standardized treatment manuals used in the study (Levin, Lindström, Bördal, Paulson-Karlsson, & Nevonen, Citation2007; Paulson-Karlsson, Bördal, Levin, Lindström, & Nevonen, Citation2013). (The manuals are written in Swedish; please contact the authors for more information about the content or translation). The clinical experience required extended treatment duration, and clinical data from the unit revealed a recovery process of up to 18 months. The high relapse rate in AN and slow progress in treatment, which is related to a lower weight gain during treatment, has been found to predict relapse (Castro, Gila, Puig, Rodriguez, & Toro, Citation2004). Therefore, the manuals were adapted to include the core components of each treatment with increased numbers of sessions over 18 months. We used a standard session length for both treatments (i.e., 50–60 min in CBT-YA and up to 90 min for FT-YA). All therapists were trained in conducting both treatments and had experience in providing such treatment before the trial.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Young Adults

At the time the trial was established, no specific treatment manual existed that focused on underweight patients. The adapted form of CBT for ED (Fairburn, Citation2008) was emerging at this time and constitutes a later version of the manual used in this trial. We used information describing the transdiagnostic theory and treatment (Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, Citation2003), which is based on bulimia nervosa focused therapy (Fairburn & Wilson, Citation1993). In addition, we used information from personal communication with Dr. Fairburn to develop a manual for the purpose of the trial. The main differences between the manual used in the present trial and the existing CBT-E manual (Fairburn, Citation2008) is that information and instructions for the therapist are less extensive in the developed manual. Although it is not as instructive, it does contain a rationale for all core components of ED psychopathology and four additional psychological mechanisms interacting with the key features of the ED, which are found in the CBT-E manual.

We used highly experienced therapists, who were expected to use their skills to formulate and review the key areas. This accounts for why specific exercises are not included to the same extent as in the CBT-E manual. One significant difference is that the number of sessions can reach up to 60, unlike the maximum of 40 sessions in the CBT-E manual for underweight patients. Otherwise, the content and structure of the manual are the same.

The sessions were divided into four phases. One psychotherapist treated each participant, with a maximum of 60 one-hour sessions. An introductory session with the participant and parents was conducted before the start of treatment. Parents were briefly informed about anorexia nervosa and the rules regarding the treatment. We explained the situations that were non-negotiable based on the patient's somatic and mental status. The therapist further emphasized that the patient's motivation and personal work were crucial to the results. Participants and parents were also allowed to ask questions and to express expectations. The purpose was to facilitate treatment by understanding the work done by the participant and to create improved cooperation between parents and participants, thus eliminating any potential obstacles. Parents were given information regarding how to support their daughters. It was clearly described that the patient was responsible for following the rationale of the treatment, and they were only there to support the patient’s effort in following the program. No specific interventions were delivered to the parents. Their role was to support, listen, and encourage their daughters to take an active role in treatment.

Phase one consisted of eight sessions, twice a week, and started with an introduction to the treatment and the multifactorial model. This phase focused on motivation to change, educating the participant about ED symptoms and their physical, mental, and emotional effects, and helping the participant to achieve regular eating habits and initiate weight gain. Phase two included three weekly sessions aimed at summarizing and evaluating Phase one and designing the next phase. Phase three consisted of up to 43 sessions, one per week, and focused on continuing regular eating, achieving a healthy weight, and exploring obstacles to weight gain and maintenance factors, such as bodily dissatisfaction and dietary rules. It also focused on clinical perfectionism, low core self-esteem, mood intolerance, and interpersonal difficulties. Phase four involved six sessions, one every other week, with the focus on stabilizing eating and weight, preventing relapse, and evaluating the treatment.

Family/Individual Therapy for Young Adults

The FT-YA manual used in this study is a further development of the manualized family therapy model by Lock, Le Grange, Agras, and Dare (Citation2001), adapted for young adults with AN. Unlike Lock et al.’s (Citation2001) model, the manual in this study offers a higher degree of individual sessions for participants and parents and excludes family meals. The model is based on the long-term clinical experience of treatment with both teenagers and young adults with AN at the unit. Similarly to Lock et al.’s (Citation2001) model, there is a theoretical basis in the structural and systemic school with narrative elements (Minuchin et al., Citation1975; Selvini Palazzoli, Citation1978; White & Epston, Citation1990). Family sessions are combined with individual sessions for participants and parents separately. Two psychotherapists offered each family a maximum of 40 sessions of 90 min each.

Phase one consists of ten sessions with the focus on food, eating, and creating a productive collaboration between participant and parents to stop the starvation. This phase has a fixed number of separated sessions (n = 3) and family sessions (n = 10). Phase two includes two weekly sessions to evaluate achieved changes and plan for the next phase. Both sessions are family sessions. Phase three consists of up to 23 sessions, one session every other week, where the participant assumes more responsibility for eating and weight gain. Focus is also on maintenance factors of the ED and helping the participant achieve a healthy life. In this phase, the participant and parents focus on age-appropriate issues and relations. Phase four involves five sessions; the first three are once per week, and the last two are one month apart. As the participant reaches a stable and healthy weight, the family reorganizes for a life and relationship without the ED. The number and order of separated and family sessions in phases three and four are not fixed; rather, they are adapted based on the needs of the participant and the family.

The CBT-YA is an individual treatment while the FT-YA includes patient and parents. The parents’ involvement in therapy is vitally important to help reduce the eating disorder symptoms and for ultimate success in treatment.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive statistics and significance tests were carried out with SPSS 24.0, also reporting the effect sizes for interpretation and consideration due to small sample sizes. An independent statistician, blinded to the treatment modalities, carried out a linear mixed model for repeated measures using Stata 12. This model is preferable when data are used on the same statistical unit [i.e., longitudinal studies containing both random and fixed effects for the within-subject factor (time) and the between-subjects factor (therapy) with estimated coefficient including 95% confidence interval (CI)]. The linear mixed model design has been shown to obtain power despite imbalance due to missing data and has an advantage over more traditional methods, such as mixed-model ANOVAs (Quené & Van den Bergh, Citation2008). The outcome measures were used as dependent variables at all time points and types of treatment as the fixed explanatory variable.

We calculated effect sizes within groups for all outcome measures using Cohen’s d. To control for Type 1 errors, a Bonferroni correction was conducted by dividing the significance level of p = 0.05 by the number of significance tests that were calculated (n = 15), resulting in a significance level of 0.003. The items in the ED Index used different scoring (0–3 and 0–4 points). The item scores were weighted to give each question equal importance and then standardized to give the ED Index a value between zero and 1, with higher values referring to a more severe degree of AN. Measures of the TSS classified participants into three groups: “highly satisfied” if all items had the highest score, “satisfied” if at least one item was intermediate, and “unsatisfied” if at least one item was scored as the least satisfying alternative.

Participant Process and Feasibility

A total number of 1,152 sessions were attended in the CBT-YA group (M = 31.1, SD = 18.9) and 1,048 (M = 28.3, SD = 12.3) in the FT-YA group. It should be noted that in the FT-YA group, the sessions were 90 min long and included two therapists. Converted into consumed hours, the calculation is 1,048 × 1.5 × 2 = 3144. This means that patients in the CBT-YA group consumed only 36% of the resources required by the FT-YA group.

Completion of treatment was defined as receiving ≥ 45 sessions of CBT-YA or ≥ 30 sessions of FT-YA, representing at least 75% of the maximum number of treatment sessions, including taking part in all phases of treatment. Thirty-one participants (42%) completed at least three-fourths of the treatments, 32% in CBT-YA and 51% in FT-YA, with no significant difference in received treatment hours (p = 0.49, d = 0.25).

Regardless of the number of sessions, early termination of treatment due to recovery could occur following an agreement between the participant and therapist. This occurred in 13.5% of cases in the CBT-YA group and 19% of cases in the FT-YA group, with no significant difference between groups (p = 0.80, d = 0.15).

Non-completers consisted of two groups. The first group was defined as those who ended treatment upon their own request, having participated in fewer than 45 sessions of CBT-YA or 30 sessions of FT-YA. In total, 19% ended treatment prematurely, 30% (n = 11) in CBT-YA (mean sessions; 23.8, range 1–44) and 8% (n = 3) in FT-YA (mean sessions; 17.6, range; 7–24), with no significant difference between groups (p = 0.46, d = 0.49). The second group of non-completers concerned those involved in adverse events, such as intermittent inpatient/day treatment, during the treatment period (0–18 months). This occurred in 17 cases (23%), with a mean duration of 16 weeks (SD = 10.8), nine (24%) in the CBT-YA group (mean duration = 18.00 weeks, SD = 13.8) and eight (22%) in the FT-YA group (mean duration = 14.37 weeks, SD = 6.50).

Regarding BMI, no significant differences were found post-treatment (p = 0.39, d = 0.2) or at FU (p = 0.31, d = 0.33) between participants who received intermittent inpatient/day treatment (post-treatment: M = 19.13, SD = 2.5; FU: M = 19.48, SD = 2.3) and outpatients (post-treatment: M = 19.58, SD = 1.6; FU = 20.1, SD = 2.1). The satisfaction rate post-treatment was 70% for participants who were either “highly satisfied” or “satisfied” (CBT-YA: 78%, FT-YA: 62%).

BMI Change

BMI increased significantly from baseline to post-treatment in both groups. The difference within groups from baseline to post-treatment showed a significant weight increase, as well as from baseline to FU, with large effect sizes > 3.0 (). There was no significant difference in BMI between post-treatment and FU in any of the groups (). The mean post-treatment BMI scores () were > 19 (i.e., CBT-YA 19.61, CI 19–20.20; FT-YA 19.33, CI 18.80–19.90) with no significant difference between treatments (p = 0.49, CI −0.51–1.06). No treatment by time interaction was detected (CI = −1.22–0.58). At FU, the mean BMI was 19.62 (CI 19.10–20.20) in the CBT-YA group and 20.26 (CI 19.70–20.80) in the FT-YA group, with no difference between the groups (p = 0.11, CI −1.43–0.15). Again, we found no effect of treatment by time interaction (CI = −0.31–1.50).

Table II. Changes within groups on the outcome, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% CI between time points.

Table III. Adjusted mean scores (LS-mean) post-treatment and at follow-up after 18 months for ED psychopathology, by treatment group. Estimated least square mean difference (Ls-Mean Diff) and confidence interval (CI) per group and estimated coefficient of the interaction effect of treatment by time with CI.

In our study groups, the number of participants with a BMI ≥17.5 post-treatment was 83%–92% in the CBT-YA group and 83%–94.5% in the FT-YA group at FU. Regarding weight restoration (i.e., BMI ≥ 18.5), a total of 62.2% in the CBT-YA group and 73% in the FT-YA group had reached a healthy BMI post-treatment (p = 0.32). At FU, a total of 64.9% and 83.8% had a BMI ≥ 18.5, respectively (p = 0.62). The CBT-YA group had an average weight gain of 3.1 kg/m2, and the FT-YA group 2.8 kg/m2 post-treatment. At FU, the average weight gain remained for the CBT-YA group but increased further in the FT-YA group (by 3.72 kg/m2).

Diagnostic Change and Change in ED Psychopathology

Diagnostic change during treatment, by treatment group, showed that 76% of participants in both groups did not meet the diagnostic criteria according to DSM-IV (APA, Citation2000). All 76% who were in full remission post-treatment were still in full remission at FU, and an additional 9% of participants had improved. shows the crossover between ED diagnoses.

Table IV. Diagnostic change during treatment and follow-up, by treatment group.

For the ED Index, participants in both groups improved between baseline and post-treatment and from baseline to FU, with large effect sizes (). The linear mixed model did not detect any significant differences between the groups or interaction effects between treatments ().

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcome data are presented in and . Participants in both groups decreased significantly (all p = 0.001) from baseline to post-treatment in ED-specific symptoms (EDRC) and general psychological symptoms, as measured by the EDI-3 composite GPMC and BDI. Also, we found medium to large effect sizes on all measures within groups, ranging from d = 0.66 for EDRC in FT-YA to d = 1.12 for BDI in FT-YA. Similar results were found from baseline to FU, with large effect sizes ranging from d = 0.81–1.5. Differences within groups between post-assessment and FU were not detected in any secondary measures; however, change within the FT-YA group on EDRC approached significance on the 0.05 level (p = 0.08), but the effect size was small (d = 0.16). We also found a small effect size on the BDI between time points 2 and 3 (d = 0.30) in the FT-YA group. Overall, we did not detect any significant treatment by time interaction across any time points.

Discussion

The present study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of manualized CBT-YA and FT-YA in an outpatient setting for young adults with AN. The quality of the evidence regarding psychotherapeutic treatments for young adults with AN is still weak. Family based therapy (FBT) is the recommended treatment for children and adolescents with AN, and CBT has been effective for adults with other eating disorders. Our study showed that CBT-YA and FT-YA in an outpatient setting improved weight, ED-specific symptoms, and general psychopathology 18 months after the beginning of the treatment. The remission rate (i.e., participants who no longer met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder) was relatively high. The relevant improvements were maintained at the 18-month FU. There was no significant superiority for the two treatments on any of the outcomes measured.

A lower weight gain during treatment and slow progress have been found to predict relapse (Castro et al., Citation2004; Treat, McCabe, Gaskill, & Marcus, Citation2008). A lower BMI has also been associated with a worse outcome in the long-term following discharge from inpatient treatment (El Ghoch et al., Citation2016). Both groups in the present study increased significantly in weight and reached a mean BMI within the normal range from baseline to post-treatment. Since it is the most severe symptom, weight restoration should be one of the main foci in treatment of underweight patients (NICE, Citation2017).

It is important to note that there are no comparable studies in several respects, especially regarding age, illness duration, treatment length, and remission. Therefore, we do not draw direct parallels to results in other studies. We do not compare the results other than to report outcomes from studies that are somewhat similar to these in order to put the results in relation to what we know about adults with AN.

The weight increase in our study is noteworthy compared to similar studies, which had mean BMIs ranging between 17.30 and 18.44 at the end of treatment (Byrne et al., Citation2017; Schmidt et al., Citation2015; Touyz et al., Citation2013; Zipfel et al., Citation2014). Without comparing these trials per se (due to different content, adherence, illness duration, and age range), our results are promising for young adults. Our findings suggest that there might be hope for a better course for young adults with less chronicity, as the recovery rates are higher than in studies with adults. To establish this course, it will be necessary to perform a long-term follow-up study. This is important to keep in mind since illness duration is a predictor of poorer outcome (Vall & Wade, Citation2015).

An interesting observation is that participants who underwent FT-YA, unlike those in the CBT-YA group, continued to increase their BMI, and the majority reached the lowest normal weight. Even though these results were not significant and the prognosis is still considered poor in AN with high relapse rates (Keel & Brown, Citation2010; Watson & Bulik, Citation2013), this result merits highlighting and could indicate that young adults during the recovery process might be in need of family support. However, almost 60% of patients in the FT-YA group moved from home during the study period. This is important predominantly for the FT-YA group, since this means that it might not be important to live with the parents during a family intervention. The support and therapy itself might be sufficient for making progress.

One can also question whether it is desirable to reach a higher BMI than the minimum normal weight (i.e., ≥ 18.5). This can only be answered by long-term follow-up (i.e., five to ten years after the last assessment). Even though no significant difference was found between the groups at FU, the effect size between the groups was 0.3 using Cohen’s d (Citation1988) (https://www.uccs.edu/lbecker/). This is considered a small to medium effect size and could be an indication that having a sufficient number of participants to establish sample statistical power might detect a significant difference with statistical accuracy. This may be the case even though a post-hoc power calculation was conducted to obtain the achieved power of the trial between groups. Using such a calculation has been criticized for not calculating a retrospective power based of the observed effect size. This has been discussed, for example, by Gilbert and Prion (Citation2016). A non-significant result will automatically lead to a low post-hoc power, since it is a reflection of the actual p-value and could, therefore, be misinterpreted. Consequently, the risk of committing a Type 2 error, i.e falsely confirming there is no difference, is imminent.

As previously mentioned, just as in the case with BMI, when placing our results in context with previous results, it is important to consider the differences between our trial and other studies. Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that it is not possible to directly compare the results. For example, remission is defined differently in outcome studies. This is a problem and has been highlighted as an important area of improvement for the comparability and generalizability of results (Watson & Bulik, Citation2013). The overall remission rate for adult AN has been estimated to be approximately 50% (Keel & Brown, Citation2010). Looking at the diagnostic change in the present study, the majority of the participants no longer fulfilled the criteria for an ED at post-assessment ().

Furthermore, the participants did not relapse after post-assessment. In fact, the total proportion of participants in full remission, according to DSM-IV (APA, Citation2000), increased at FU. This is an intriguing and impressive result and is in sharp contrast to the reported relapse rates of 35% (after 15 months) and 41% (after 12 months) (Carter et al., Citation2011). Although it is not possible to draw a direct parallel as indicated above, recovery rates in the study by Zipfel et al. (Citation2014) were between 13% and 36% at 12-month FU. Recovery in Zipfel et al.’s (Citation2014) research was defined as having a BMI ≥17.5 and a score of 1–2 on a six-point scale on the Psychiatric Status Rating scale measuring the severity of the ED. As an extension, it is worth emphasizing the importance of early detection and offering treatment before the disorder progresses.

The ED Index mirrors key features of AN. Since the remission rates are high, the significant differences between pre- and post-assessment on these measures are in accordance. Participants in both groups decreased their symptoms on expert ratings (i.e., RAB-R). Treatment of AN should focus on key features (NICE, Citation2017), and the results show that a significant change has occurred that suggests both treatments target and reduced AN symptoms.

Interpreting all measured outcomes together, objective measures, expert ratings, and self-reports appear consistent. A significant change was established on all measures from pre- to post-assessment and FU. The participants in the present study exhibited high levels of depressive symptoms at baseline, according to the BDI, and scored above the cut-off on the GPMC (Nyman-Carlsson et al., Citation2015), with significant improvement at post-treatment and FU. It has been suggested that it is not necessary to treat specific comorbidities, such as depression or anxiety in most cases, since they will subside as a consequence of treating the ED (Fairburn, Citation2008). The results of this study are in line with these suggestions. Regardless of the treatment type, general psychopathology improves during treatment.

When comparing the received treatment hours in the study groups in the present study, about 70% of participants in the FT-YA group completed more than half of the maximum offered sessions, and 45% of the CBT-YA group completed less than half of the offered sessions. Yet they all improved and achieved remission (i.e., they no longer fulfilled the diagnostic criteria) to the same extent. Even though participants in the FT-YA group continued to increase in weight from treatment completion to FU, we cannot state the long-term benefit, because we lack further data beyond this point. Participants in the CBT-YA group appear to have improved to the same extent while requiring a significantly smaller amount of resources; taking into account both the doubled amount of therapeutic hours in FT-YA (since two therapists attended each session) and the effort and resources it takes to involve parents. Based on the outcome in both groups, one could note that it might be more cost-effective to both receive and offer CBT-YA related to investments by family, time, and therapist resources. Although the relative cost would be 54% higher when offering FT-YA regarding therapeutic resources, it would not be a reasonable extra cost to pay for the effect. Also, the majority of the participants (70%) in the CBT-YA group ended treatment before the 45th session, and treatment length did not affect the outcome. In FT-YA, however, approximately 70% of participants completed almost the full set of sessions.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this study is that it was conducted in a naturalistic clinical setting. Turner and colleagues (Turner, Marshall, Stopa, & Waller, Citation2015) emphasized the importance of this routine clinical environment. RCTs often have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, which can reduce the generalizability, but the criteria used in the present study resulted in a sample reflecting the case-mix encountered in everyday clinical outpatient practice. Experienced psychotherapists who were involved in developing the treatment manuals conducted the treatments. This experience strengthened their motivation and competence in adhering to the manuals, strengthened the study’s fidelity, and bridged the gap between research and practice.

Given that there was only one missing data point of BMI at post-assessment and three at FU, this study provides a unique data set compared to any other studies on young adult AN patients. The average dropout rate in similar studies has been estimated to be approximately 20–30% (Watson & Bulik, Citation2013).

Conducting researching within a single center leads to a long inclusion period (due to the low incidence of AN), which affects the statistical power. No explicit assumptions can be made if examining either non-inferiority or superiority regarding any of the two treatments. However the lack of interaction effect could simply be a reflection of the study being underpowered.

ED treatment is free of charge for patients in Sweden, which means that patients can seek treatment all over the country and choose from different kinds of treatment. It might also interfere with ecological validity, since the sample is linked to a single center and a specific area in Sweden. We did not use a waiting control group for ethical reasons due to the severity of the disorder. Neither did we use a comparison group serving as treatment as usual since both treatments were already implemented as standard treatments at the clinic. Moreover, a potential problem with comparing the two interventions could be that the FT-YA manual was based on an established treatment method for children and adolescents, while CBT-E was, at the time of the trial, a sparsely evaluated treatment for this patient population.

Approximately one-fourth of the participants required more intensive treatment, which affected the interpretation of the results, although there was no significant difference regarding weight restoration at post-treatment. Other potential limitations may be the lack of external validation, measures of treatment adherence, or blinding of allocation to the primary investigator and research leader who conducted recruitment and assessment. Another possible confound could be that the replaced therapist, unlike the other four therapists, had not taken part in developing the treatments. The maximum number of sessions provided differs from other studies of CBT and FBT, which makes it difficult to compare to other studies of similar treatments.

The design of the trial and the lack of a priori power calculations based on either a non-inferiority or superiority margin might be viewed as a limitation today. This hinders the possibility of making adequate comparative analyses between the groups due to low power and the lack of comparative margin. However, this sample is unique in several ways, and the results of this study are nevertheless of sufficient interest to report.

Future Directions

In addition to the results we have presented in the present study, further analysis of cost-effectiveness between the two therapies is an important future direction. Although participants in both groups made improvements, the related costs for each treatment and outcome might be different. Examining the adherence to the manuals is also an important aspect. Establishing fidelity to the core treatments is possible by analyzing existing audiotaped sessions from this trial.

Conclusions

The results strongly suggest that both individual CBT-YA and FT-YA are effective treatments for young adults with AN in regard to weight restoration, reduced ED psychopathology, and general psychological problems commonly associated with an ED. The outcome of this trial indicates that both treatments seem to be feasible, acceptable, and potentially beneficial for this population. Comparative efficacy will require a larger multiple site study applying the current outcome measures.

This study represents the natural course of patients coming to a treatment unit for ED. We describe a treatment process that closely resembles the everyday clinical life for patients and therapists. By not excluding patients who have received additional treatment or not completed all sessions, we mirror the true clinical setting for patients and therapists, which increases the possibility for clinicians to interpret and implement the results. Studies conducted in strict research environments are often difficult to apply directly to clinical reality. However, well-controlled trials account for confounding factors and decrease the risk of biases. Both perspectives are important, especially for the individual therapist searching for new knowledge to apply in their clinical work with patients.

The outcome of this randomized study shows that young patients with AN benefit from both individual treatment and family interventions. Examining the direct costs for each treatment would also be of interest, as would studies addressing factors that might play a part in the outcome of the separate therapies and predisposing factors that may be indicative in selecting treatment.

| List of Abbreviations | ||

| AN | = | anorexia nervosa |

| BDI | = | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BMI | = | body mass index |

| CBT-E | = | enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy |

| CBT-ED | = | individual eating disorder focused on cognitive behavioral therapy |

| CBT-YA | = | cognitive behavioral therapy for young adults |

| CI | = | confidence interval |

| DSM | = | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| ED | = | eating disorders |

| EDI-3 | = | Eating Disorders Inventory-3 |

| FBT | = | Family-based treatment |

| FU | = | follow-up |

| FT-YA | = | combined family/individual therapy for young adults |

| MANTRA | = | Maudsley anorexia nervosa treatment for adults |

| RAB-R | = | Ratings of Anorexia and Bulimia Revised |

| RCT | = | randomized controlled trial |

| SSCM | = | specialist supportive clinical management |

| TSS | = | Treatment Satisfaction Scale |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the therapists in the study: Marianne Lindström, Birgitta Levin, Anneli Bördal, and Ulrika Ehres, together with one of the authors (GPK). The authors also thank Thomas Hermander, Ingrid Hjalmers, and Carina Pettersson at the Anorexia and Bulimia Unit at Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, and Arian Barakat and Marcus Thuresson for statistical consultation. In particular, the authors thank the patients and parents for participating.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: Author.

- Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

- Ball, J., & Mitchell, P. (2004). A randomized controlled study of cognitive behavior therapy and behavioral family therapy for anorexia nervosa patients. Eating Disorders, 12(4), 303–314. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260490521389

- Beck, A., Steer, R., & Carbin, M. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(1), 77–100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

- Brockmeyer, T., Friederich, H. C., & Schmidt, U. (2018). Advances in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: A review of established and emerging interventions. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1228–1256. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002604

- Byrne, S., Wade, T., Hay, P., Touyz, S., Fairburn, C. G., Treasure, J., … Crosby, R. D. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 47(16), 2823–2833. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717001349

- Carter, F. A., Jordan, J., McIntosh, V. V., Luty, S. E., McKenzie, J. M., Frampton, C. M., … Joyce, P. R. (2011). The long-term efficacy of three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(7), 647–654. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20879

- Castro, J., Gila, A., Puig, J., Rodriguez, S., & Toro, J. (2004). Predictors of rehospitalization after total weight recovery in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36(1), 22–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20009

- Clausen, L., Rosenvinge, J. H., Friborg, O., & Rokkedal, K. (2011). Validating the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3): A comparison between 561 female eating disorders patients and 878 females from the general population. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(1), 101–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-010-9207-4

- Clinton, D., Björck, C., Sohlberg, S., & Norring, C. (2004). Patient satisfaction with treatment in eating disorders: Cause for complacency or concern? European Eating Disorders Review, 12, 240–246. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.582

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (3rd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Dalle Grave, R., El Ghoch, M., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2016). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa: An update. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(1), 2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0643-4

- Dare, C., Eisler, I., Russell, G., Treasure, J., & Dodge, L. (2001). Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: Randomised controlled trial of out-patient treatments. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 216–221. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.3.216

- El Ghoch, E., Calugi, M., Chignola, S., Bazzani, E., V, P., & Dalle Grave, R. (2016). Body mass index, body fat and risk factor of relapse in anorexia nervosa. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(2), 194–198. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.164

- Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behavior Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

- Fairburn, C. G., & Wilson, G. T. (Eds.). (1993). Binge eating, nature, assessment and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Fisher, C. A., Hetrick, S. E., & Rushford, N. (2010). Family therapy for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 14(4), CD004780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004780.pub2

- Garner, D. M. (2004). Eating disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3). Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

- Gilbert, G. E., & Prion, S. K. (2016). Making sense of methods and measurement: The danger of the retrospective power analysis. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 12(8), 303–304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2016.03.001

- Hay, P. J., Claudino, A. M., Touyz, S., & Abd Elbaky, G. (2015). Individual psychological therapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 27(7), CD003909. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003909.pub2

- Keel, P. K., & Brown, T. A. (2010). Update on course and outcome in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(3), 195–204. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20810

- Levin, B., Lindström, M., Bördal, A., Paulson-Karlsson, G., & Nevonen, L. (2007). Anorexia nervosa: A transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy. A treatment manual for young adults. (In Swedish): Aetolia, Supplement no. 1.

- Lock, J., Le Grange, D., Agras, W. S., & Dare, C. (2001). Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach (1st ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Micali, N., Hagberg, K. W., Petersen, I., & Treasure, J. L. (2013). The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000-2009: Findings from the general practice research database. British Medical Journal Open, 3(5), doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002646

- Minuchin, S., Baker, L., Rosman, B. L., Liebman, R., Milman, L., & Todd, T. C. (1975). A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children. Family organization and family therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32(8), 1031–1038. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760260095008

- Nevonen, L., Broberg, A. G., Clinton, D., & Norring, C. (2003). A measure for the assessment of eating disorders: Reliability and validity studies of the Rating of Anorexia and Bulimia interview - revised version (RAB-R). Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44(4), 303–310. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00349

- NICE. (2017). Eating Disorders: Recognition and treatment. Retrieved May 17, 2017, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-161214767896

- Nyman-Carlsson, E., Engstrom, I., Norring, C., & Nevonen, L. (2015). Eating Disorder Inventory-3, validation in Swedish patients with eating disorders, psychiatric outpatients and a normal control sample. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(2), 142–151. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2014.949305

- Paulson-Karlsson, G., Bördal, A., Levin, B., Lindström, M., & Nevonen, L. (2013). Family therapy: A treatment manual for young adults with anorexia nervosa. (In Swedish): Aetolia, supplement no. 1.

- Quené, H., & Van den Bergh, H. (2008). Examples of mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects and with binomial data. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 413–425. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2008.02.002

- Schmidt, U., Magill, N., Renwick, B., Keyes, A., Kenyon, M., Dejong, H., … Landau, S. (2015). The maudsley Outpatient Study of Treatments for Anorexia Nervosa and Related Conditions (MOSAIC): Comparison of the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM) in outpatients with broadly defined anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(4), 796–807. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000019

- Selvini Palazzoli, M. (1978). Self-starvation: From individual to family therapy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. New York: Jason Aronson.

- Smink, F. R., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Report, 14(4), 406–414. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

- Steinhausen, H. C. (2002). The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(8), 1284–1293. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284

- Stice, E., Marti, C. N., & Rohde, P. (2013). Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 445–457. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030679

- Stuhldreher, N., Konnopka, A., Wild, B., Herzog, W., Zipfel, S., Lowe, B., & Konig, H. H. (2012). Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(4), 476–491. doi 10.1002/eat.20977

- Touyz, S., Le Grange, D., Lacey, H., Hay, P., Smith, R., Maguire, S., … Crosby, R. D. (2013). Treating severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2501–2511. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291713000949

- Treasure, J., Claudino, A. M., & Zucker, N. (2010). Eating disorders. The Lancet, 375(9714), 583–593. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61748-7

- Treat, T. A., McCabe, E. B., Gaskill, J. A., & Marcus, M. D. (2008). Treatment of anorexia nervosa in a specialty care continuum. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(6), 564–572. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20571

- Turner, H., Marshall, E., Stopa, L., & Waller, G. (2015). Cognitive-behavioural therapy for outpatients with eating disorders: Effectiveness for a transdiagnostic group in a routine clinical setting. Behavior Research and Therapy, 68, 70–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.03.001

- Vall, E., & Wade, T. D. (2015). Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(7), 946–971. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22411

- Walker, E., & Nowacki, A. S. (2011). Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(2), 192–196. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1513-8

- Wang, Y.-P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35, 416–431. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

- Watson, H. J., & Bulik, C. M. (2013). Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2477–2500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291712002620

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Zeeck, A., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Friederich, H. C., Brockmeyer, T., Resmark, G., Hagenah, U., … Hartmann, A. (2018). Psychotherapeutic treatment for anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 158. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00158

- Zipfel, S., Giel, K. E., Bulik, C. M., Hay, P., & Schmidt, U. (2015). Anorexia nervosa: Aetiology, assessment, and treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(12), 1099–1111. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00356-9

- Zipfel, S., Wild, B., Gross, G., Friederich, H. C., Teufel, M., Schellberg, D., … Herzog, W. (2014). Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): Randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9912), 127–137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61746-8