Abstract

Objective: Although teletherapy is increasingly common, very little is known about its impact on therapeutic relationships. We aimed to examine differences between therapists’ experiences of teletherapy and in-person therapy post-pandemic with regard to three variables pertinent to the therapeutic relationship: working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence.

Methods: In a sample of 826 practicing therapists, we examined these relationship variables, as well as potential moderators of these perceived differences including professional and patient characteristics and covid-related variables.

Results: Therapists reported feeling significantly less present in teletherapy and their perceptions of the real relationship were somewhat impacted, but there were no average effects on their perceived quality of the working alliance. Perceived differences in the real relationship did not persist with clinical experience controlled. The relative reduction in therapeutic presence in teletherapy was driven by the ratings of process-oriented therapists and therapists conducting mostly individual therapy. Evidence for moderation by covid-related issues was also found, with larger perceived differences in the working alliance reported by therapists who used teletherapy because it was mandated and/or not by choice.

Conclusion: Our findings might have important implications for generating awareness around the therapists’ lowered sense of presence in teletherapy compared to in-person teletherapy.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: Unlike previous teletherapy research, this teletherapy research was done at the tail end of the pandemic, which means that results were not influenced by pandemic-related stress or the forced transition to teletherapy. Compared to their experience with in-person sessions, therapists felt less present and a little less real and genuine with their patients in teletherapy, but they did not perceive a difference in the working alliance.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of tele-psychotherapy via videoconferencing (teletherapy) has increased 26-fold, with one study estimating that 67% of American psychologists conduct all of their clinical work with teletherapy (Pierce et al., Citation2021). Even though the use of teletherapy is no longer mandated in most regions due to pandemic-related social restrictions, teletherapy has become part of standard practice for many clinicians (Kwok et al., Citation2022; Sheperis & Smith, Citation2021; Van Daele et al., Citation2020; Yellowlees & Nafiz, Citation2010). However, as of yet relatively little is known about how teletherapy impacts therapeutic processes.

Initial evidence indicates that neither patient post-treatment and follow-up outcomes nor attrition rates differ between in-person and teletherapy formats (Lin, Stone, Heckman, & Anderson, et al., Citation2021). However, the use of teletherapy might still represent a different kind of therapeutic encounter (Aafjes-van Doorn, Citation2022). Therapists have anecdotally described this difference as “I think the shape is very different, but I wouldn’t qualify it as lesser or more. It’s not quantitative. It’s just very different but equally rewarding.” (Shklarski et al., Citation2021, p. 268) or “there is just a different energy.” (McCoyd et al., Citation2022, p. 8). These quotes suggest that, beyond technical and administrative challenges, there may be relational challenges in teletherapy as suggested by research conducted both pre- (Rees & Stone, Citation2005) and post-pandemic (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés et al., Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2021; Shklarski et al., Citation2021). For example, some clinicians have expressed concerns about the ability to build a working alliance in teletherapy in the absence of interpersonal contact and physical presence (Lin et al., Citation2021). It might be more difficult to express empathy, genuineness, or warmth, to convey emotional and relational information, or to recognize patients’ feelings, when non-verbal communication is hindered by limited visual cues and direct eye contact (Burgoyne & Cohn, Citation2020). Moreover, the potential for environmental distractions may make the encounter less present or may lead either therapist or patient to miss subtle nuances in the interaction. The goal of this preregistered study was to examine differences between therapists’ experiences of teletherapy and in-person therapy with regard to three variables that are considered important for describing therapeutic relationships: working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence.

Working Alliance, Real Relationship, and Therapeutic Presence

The working alliance, or the relationship between therapist and patient in which they strive to work together to achieve positive changes for the patient, is an established feature of effective therapy (Bordin, Citation1979; Flückiger et al., Citation2018). Pre-pandemic research suggests that the working alliance is usually similar in teletherapy and in-person therapy (Berger, Citation2017; Holmes & Foster, Citation2012; Morland et al., Citation2015; Norwood et al., Citation2018; Reynolds et al., Citation2013; Richards et al., Citation2018; Simpson & Reid, Citation2014; Stubbings et al., Citation2013; Watts et al., Citation2020), particularly when potential barriers such as therapist confidence, assumptions, and experience were accommodated (Simpson & Reid, Citation2014). With some exceptions (e.g., Rotger & Cabré, Citation2022), most studies conducted during the pandemic likewise reported no significant differences between working alliance scores provided by both therapists and patients in teletherapy and in-person therapy (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés et al., Citation2021). Alliance also continues to be predictive of treatment outcome in teletherapy (Cataldo et al., Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2022). This suggests that although a transition to teletherapy might create discomfort, uncertainty, and professional doubt for the therapist, the actual experience of the working alliance might still be very similar to that in in-person therapy, and just as important for treatment progress.

Less is known about the impact of teletherapy on the real relationship, or the extent to which therapist and patient are genuine and perceive each other realistically (Gelso, Citation2014). Whereas working alliance specifically pertains to therapeutic relationships, the real relationship exists in all relationships (Gelso et al., Citation2005). It is thought to have two aspects, realism and genuineness. Realism refers to the “experiencing or perceiving the other in ways that befit him or her, rather than as projections of wished-for or feared others (i.e., transference)” (p. 37). Genuineness refers to “the ability to be who one truly is, to be non-phony, to be authentic in the here and now” (Gelso, Citation2002, p. 37). Research suggested that the quality of the real relationship is positively related to treatment outcome, and although the real relationship is highly related to the working alliance, some studies indicated that it also predicts unique variance in outcome in in-person therapy (Gelso, Citation2014; Gelso et al., Citation2018). Initial studies indicated that therapists may actually report relatively higher quality of real relationship in teletherapy than in in-person therapy (Aafjes-van Doorn, Békés, & Prout, Citation2020; Békés et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). Anecdotally, while therapists in these studies reported difficulties with communicating empathy, missing nonverbal signs, and maintaining rapport, they also described a newfound authenticity and realism in the relationship and new ways to access the patients’ experience (Békés, Aafjes-van Doorn, Roberts, Prout, & Hoffman, Citation2023).

Therapeutic presence is regarded as a third distinct relational element of therapeutic relationships (Geller & Greenberg, Citation2002). Presence occurs when therapists bring their whole self to the encounter with patients and are fully in the moment physically, emotionally, cognitively, relationally, and spiritually (Geller, Citation2017; Geller et al., Citation2010; Geller & Greenberg, Citation2002, Citation2012; Hayes & Vinca, Citation2011, Citation2017). This posture is thought to help therapists attune to their own moment-to-moment experiences as well as those of their patients (Geller, Citation2017; Thompson, Citation2018), serve as a co-regulator of patients’ emotions (Geller, Citation2019), and evoke psychological and emotional safety (Geller & Porges, Citation2014). The cultivation and maintenance of therapeutic presence in teletherapy has been argued to be a precondition for effective therapeutic relationships and a positive working alliance (Geller, Citation2021; Haddouk et al., Citation2018; Hilty et al., Citation2019; Ruble, Romanowicz, Bhatt-Mackin, Topor, & Murray, Citation2021), although thus far evidence is ambiguous (Geller et al., Citation2010). Given the many potential technical distractions and concerns about not feeling connected in teletherapy (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2020) it seems likely that the experience of therapeutic presence would be more challenging to achieve. Overall, based on limited previous research and theoretical considerations, we would expect therapists’ experience of the therapeutic alliance to be unaffected, the real relationship to be higher, and therapeutic presence to be lower in teletherapy as compared to in-person therapy.

Treatment and Therapist Characteristics

There are reasons to think that the impact of teletherapy on the therapeutic relationship may depend on characteristics of the therapist, patient, or treatment. For instance, several studies conducted during the pandemic have suggested that compared to cognitive and behavioral therapies (CBT), experience-oriented therapies are more affected by relational factors. In CBT, a therapist tends to focus on conscious verbal communication, and explicit tasks (completion of a thought record, development of a behavioral experiment). These features may be more easily retained in videoconferencing than factors thought to be therapeutic in relational treatments, such as psychological contact, trust, intimacy, unconscious processes, or affective dynamics (Mearns & Cooper, Citation2017). Similarly, questions have been raised about the suitability of teletherapy for emotion-focused or process-oriented treatments because the format may make it more difficult to access emotions as effectively or deeply as face-to-face interactions (Thompson-de Benoit & Kramer, Citation2021). These studies may imply that the impacts of teletherapy may be stronger for relational or process-oriented therapists than CBT therapists. Nevertheless, studies at the start of the pandemic suggest that many relational therapists felt that the therapeutic relationship with their teletherapy patients remained as strong, connected, and authentic as in the in-person sessions (Békés et al., Citation2020).

Compared to the vast amount of research on teletherapy for individual adult patients, the literature on teletherapy with couples, families, and children is limited (Borenstein, Citation2022; Boydell et al., Citation2014; Burgoyne & Cohn, Citation2020; Udwin et al., Citation2021), and concerns have been voiced about the potentially negative impact of teletherapy with these kinds of patients (Burgoyne & Cohn, Citation2020; Heiden-Rootes et al., Citation2021; Thompson-de Benoit & Kramer, Citation2021; Udwin et al., Citation2021). Moreover, studies conducted during the pandemic suggest that therapists who were older, more experienced, and female had more positive experiences with providing teletherapy during the pandemic (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., 2020; Békés et al., Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2021). Thus far, no study has examined how technical considerations such as mask use or teletherapy mandates have affected therapeutic relationships. Overall, research on potential moderators of the impacts of teletherapy on relational variables is limited. We expected any differences we find between teletherapy and in-person therapy to persist regardless of therapeutic orientation and experience, but also planned to explore potential moderators of relational differences across therapy formats.

The Current Study

Although there is some initial evidence regarding differences in the therapeutic relationship between teletherapy and in-person therapy, thus far research about these differences post-pandemic has been limited. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine differences in the working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence as reported by therapists who conducted both in-person and teletherapy at the tail end of the COVID-19 pandemic, to determine whether these differences persisted with therapist, patient, and situational variables controlled for, and to examine potential moderators of any observed differences. This study advances previous research in several ways.

First, most previous studies that reported on the therapists’ relational challenges in teletherapy surveyed therapists about their teletherapy experiences but did not directly compare their perception of teletherapy to the reported experiences of the same therapists’ experiences in in-person therapy. Notable exceptions are two studies that directly compared the differences between in-person and teletherapy with regards to therapeutic skills (Lin et al., Citation2021) and interventions (Probst et al., Citation2021). However, neither of these studies focused on working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence specifically. Probst and colleagues compared teletherapy and in-person therapy in terms of specific techniques (Solomonov et al., Citation2019), and found that all techniques were scored higher in in-person therapy than teletherapy (Probst et al., Citation2021). They interpreted this finding as suggesting that therapists in teletherapy used fewer approach-specific techniques. Lin et al. (Citation2021) examined differences in helping and facilitative interpersonal skills as well as the therapeutic bond, and similarly found that scores for all these items were lower in teletherapy than in-person therapy, although this difference was smaller in women than in men (Lin et al., Citation2021). Overall, these studies suggest that therapists perceive less activity in teletherapy, particularly in terms of therapeutic techniques. However, they do not get directly at the nature of the relationship as we do here by focusing on the working alliance in addition to real relationship, and therapeutic presence.

Moreover, these two studies, like all teletherapy studies conducted in recent years, were conducted within the context of the global public crisis (data collected in 2020; Lin et al., Citation2021; Probst et al., Citation2021). This means that findings about the experiences in teletherapy were confounded by the global distress present at the time, and thus might not be generalizable to post-pandemic times. The rapid (often forced) transition to teletherapy could have affected therapists’ perception of teletherapy, especially for those who had no prior experience in teletherapy. Also, global distress meant that many therapists may have been experiencing vicarious trauma (Aafjes-van Doorn, Békés, Prout, and Hoffman, Citation2020), burnout, and concern about their own health (Békés et al., Citation2021; Prasad et al., Citation2021). Moreover, a large proportion of these survey respondents were not delivering any in-person services at the time of survey completion. Therefore, new evidence is needed to understand how the therapeutic relationship differs in in-person and teletherapy post-pandemic.

Our first aim was to examine whether and how therapists’ perception of working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence in teletherapy differ from experiences in in-person therapy. Based on previous studies conducted during the pandemic, we hypothesized that therapists would report higher levels of real relationship, similar levels of working alliance, and lower levels of therapeutic presence in teletherapy compared to in-person therapy. We also examined any potential nuance in different aspects of the working alliance and the real relationship. We expected relational differences between the treatment formats to persist, regardless of therapists’ therapeutic orientation and clinical experience.

Second, we explored whether professional, patient, and pandemic-related characteristics moderated the impacts of in-person and teletherapy on these relational variables. We considered the potential moderating effects of therapists’ clinical experience, therapeutic orientation, individual patients vs couples/families/groups, treatment of adults vs children/adolescents, and covid-related factors including use of a mask in in-person therapy, mandated use of teletherapy, and therapists’ choice of using teletherapy.

Methods

Procedures

The study was pre-registered at https://osf.io/qa382/?view_only=ab5158d0656845a6af654937d5b3470e and approved by the [local—omitted for peer review] institutional review board. This study reflects the listed seventh hypothesis in the preregistration. We collected survey data from practicing therapists who were recruited via a post on national and international professional email listservs for licensed clinicians (targeting different mental health professions, therapeutic orientations, and patient populations) and graduate programs in counseling, clinical psychology and social work, as well as professional networks. In addition, information about the study was posted on international social media groups for mental health professionals worldwide (facebook, reddit). English speaking licensed therapists and therapists in training were invited to participate if they had conducted teletherapy via videoconferencing at least once in the past three years. Participants were provided with additional information on an online Qualtrics-hosted platform before they consented to participate. The anonymous survey took about 20 min to complete and included standardized scales as well as individual items regarding experiences with providing psychotherapy in both in-person and in telepsychotherapy types. No reimbursement was provided for completing the survey (financial or otherwise).

Participants

A total of 1354 participants responded to the study’s survey, and 826 of whom completed at least one of the three standardized relational measures were included in the present study. All study data were collected between March 08, 2022 and June 30, 2022, a period of time during which the COVID-19 incidence rate was relatively low and the social restrictions and mask requirements had been lifted in most countries. Detailed demographic data about the study sample is presented in . The average age of the participating therapists’ (N = 826) was 43.01 years old (SD = 16.78). Most therapists identified as women (n = 536; 64.9%), White (N = 556, 67.3%), and North American (N = 761; 92.1%). Most of the therapists were licensed (n = 689, 83.4%), with an average of 10.74 years (SD = 6.92) of clinical experience and 15.63 sessions (SD = 10.53) per week. Most participating therapists identified with a psychodynamic approach (N = 241, 29.2%), worked with adults (N = 575, 69.5%), and primarily treated individuals (N = 699, 85.0%). Therapists reported that 60.43% of their sessions were in-person, and in most cases both they and their patient wore a mask.

Table I. Descriptive statistics (N = 826).

Measures

The online survey including individual questions and standardized measures can be found at https://osf.io/qa382/?view_only=ab5158d0656845a6af654937d5b3470e. Each standardized measure was administered twice, first regarding their experience with teletherapy via videoconferencing, and then regarding their experience with in-person therapy. The instruction of the original measures was adapted to ask participants to reflect on their “typical experience” in in-person and in teletherapy (an adaptation from the original instruction to complete the scale in reference to a specific session).

Working Alliance. Therapeutic alliance was assessed with the Working Alliance Inventory—Short Revised—Therapist (WAI-SRT; Hatcher & Gillaspy, Citation2006). The WAI-SRT is a 10-item scale that uses a five-point Likert scale, ranging from seldom (1) to always (5). Following Bordin’s (Citation1979) theoretical model, the WAI-SRT has three subscales: Bond, Goal, and Task. For the in-person responses, Cronbach's α for the WAI-SRT overall score was .90, and 84, .75, .80 for the bond subscale, task subscale and goal subscale respectively in in-person therapy. For the teletherapy responses, Chronbach’s alpha was .89 for the WAI-SRT overall score, and .82, .70 and .80 for the bond subscale, task subscale and goal subscale respectively.

Real Relationship. The Real Relationship Inventory Therapist Form (RRI-T; Gelso et al., Citation2005) was used to assess the real relationship. It includes scales measuring realism and genuineness. The RRI-T has altogether 24 items to rate on a 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). In our teletherapy and in-person therapy responses, Cronbach's α for the RRI-T overall score were both .87. The Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales realism and genuineness were .73 and .76 for in-person therapy and.72 and .74 for teletherapy.

Therapeutic Presence. The Therapeutic Presence Inventory Therapist (teletherapy-T; Geller et al., Citation2010) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire regarding the therapist’s in-session experience with various aspects of therapeutic presence, including physical, emotional, cognitive, relational, and spiritual aspects. Participants respond on a 7-point Likert sale, ranging from Not at all (1) to Completely (7). Cronbach's alpha in the in-person responses was .79, and the teletherapy responses was .80.

We created binary scores for each of the potential covariates/moderators except therapist experience and the covid-related variables, which were continuous variables. For therapeutic orientation, we distinguished between cognitive and/or behavioral (CBT) approaches and process-oriented approaches (including humanistic, psychodynamic/analytic, and systemic) based on rates and theoretical differences between these approaches. We collapsed the treatment categories into binary variables to establish therapy type (individual vs couple/family/group), and patient population (adults vs children/adolescents). Gender was treated as a binary variable (1 = female, 2 = male), due to the small number of nonbinary participants (n = 13).

Data Analysis

No missing data were imputed; we only included participants who had no missing data on a given subscale or measure. See Supplementary Table S1 for the correlations between the variables. Following our pre registration, we compared in-person and teletherapy in terms of alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence across in-person and teletherapy conditions using paired sample t-tests to test the first question. We also explored potential differences at the subscale level and included therapeutic orientation and clinical experience as covariates. To address the second research question, we added between-person moderator variables in a mixed ANOVA to test whether they moderated differences in working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence between in-person and teletherapy. To illustrate the direction of the moderation effects of the continuous covid-variables, the figures show these variables as binary, using median split. We used a type 1 error rate of .01 for all analyses.

Results

Differences in Relational Experiences In In-person and Teletherapy

presents the mean differences in relational variables between in-person and teletherapy. As predicted, we found no significant differences in reported levels of the working alliance across teletherapy and in-person therapy. Contrary to our prediction, the real relationship was perceived as significantly stronger in in-person sessions than in teletherapy sessions, although the effect was small (Hedges’s g = −.07). As predicted, therapeutic presence was also rated higher in in-person treatments than in teletherapy (Hedges’s g = −.21). After controlling for clinical experience, scores for therapeutic presence in teletherapy remained significantly lower compared to scores for in-person sessions. However, differences in the overall quality of the real relationship became nonsignificant.

Table II. Comparison of relational variables for in-person therapy vs. teletherapy.

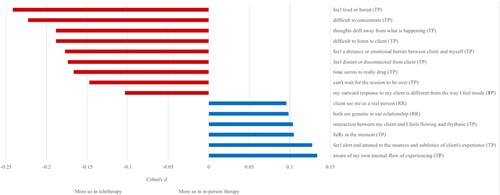

We identified 15 specific items for which the difference between therapy modalities was .10 standard deviations (Cohen’s d = .10) or greater (; see Supplementary Table S2 for full item-level results). As expected based on the results described above, nearly all of these items had to do with therapeutic presence. All the negatively-worded items reflected the teletherapy context, whereas the positive relational statements were endorsed more in in-person therapy. Therapists reported feeling more bored and finding it more difficult to concentrate in teletherapy sessions, whereas they indicated that they were more aware of their patients’ experience in-person.

Figure 1. Effect sizes of the 15 items that differed the most between in-person and teletherapy.

Note: We selected all the items with an effect size d ≥ .10. The original items were paraphrased in the figure. The center line indicates no difference, positive numbers indicate larger values in-person, and negative values indicate larger values in teletherapy. (TP) = the item is from the therapeutic presence measure; (RR) = the item is from the real relationship measure.

The Role of Professional, Patient, and Covid-related Characteristics on Perceived Relational Differences Between In-Person and Teletherapy

Mixed ANOVA analyses showed that there was no significant main effect of gender, and no significant interaction between therapist gender and differences between in-person versus teletherapy scores for the working alliance, real relationship, or therapeutic presence. Similarly, there was no significant main effect and no significant interaction between clinical experience and differences between in-person versus teletherapy scores for any of the relational variables. For a table of the means and standard deviations of the categories of therapeutic orientation, patient population, and treatment type, see Supplementary Table S3.

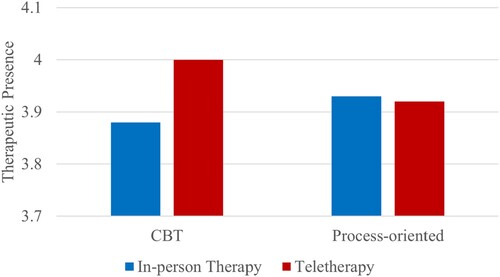

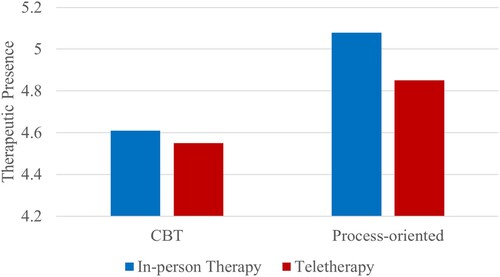

There was a significant main effect of therapeutic orientation (CBT/process-orientation) on working alliance (p = .009, η2 = .01, d = 0.2) and therapeutic presence (p < .000, η2 = .05, d = 0.5). The interaction between therapeutic orientation and differences in overall working alliance was significant (p = .001, η2 = .02). That is, CBT therapists reported larger differences in working alliance relative to process-oriented therapists, with lower working alliance scores in in-person therapy and higher working alliance scores in teletherapy, compared to their process-oriented colleagues (see ). Similarly, the interaction between therapists’ orientation and perceived differences in therapeutic presence was significant (p = .003, η2 = .02). Process-oriented therapists reported larger differences in therapeutic presence, albeit higher therapeutic presence ratings in both in-person and teletherapy than their CBT-oriented colleagues (see ). For the real relationship, there was no significant main effect of therapeutic orientation, and also no significant interaction by therapeutic orientation.

Figure 2. Working alliance differences between in-person and teletherapy by therapeutic orientation.

Note: The Y-axis does not start at 0 and does not reflect the full Likert scale of the measure.

Figure 3. Therapeutic presence differences between in-person and teletherapy by therapeutic orientation.

Note: The Y-axis does not start at 0 and does not reflect the full Likert scale of the measure.

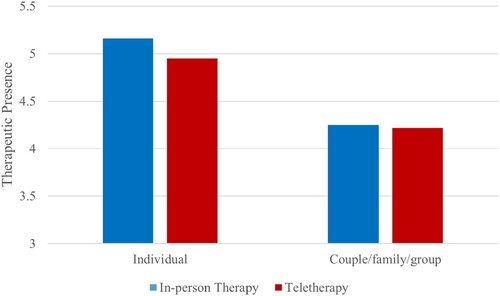

Further exploratory analysis on the possible moderation of therapy type (therapists treating mostly individual patients versus mostly couples/families/groups) showed that neither the main effect of therapy type, nor the interaction between therapy type and difference between in-person and teletherapy ratings, were significant for the working alliance and the real relationship. For therapeutic presence, the main effect of therapy type was significant (p < .001, η2 = .03, d = 0.3), as was the interaction of therapy type on differences between in-person versus teletherapy (p = .002, η2 = .02, ). Therapists conducting mostly individual therapy reported larger therapeutic presence differences, with lower therapeutic presence in teletherapy than in in-person, but still higher than the level of therapeutic presence reported by therapists who mainly treat couples/families/groups. Although the main effects for population type (adults vs adolescents and children) were significant for the real relationship (p = .005, η2 = .01, d = .02) and therapeutic presence (p < .001, η2 = .05, d = 0.5), the interaction effects were not significant on any of the relational variables.

Figure 4. Therapeutic presence differences between in-person and teletherapy by therapy type.

Note: The Y-axis does not start at 0 and does not reflect the full Likert scale of the measure.

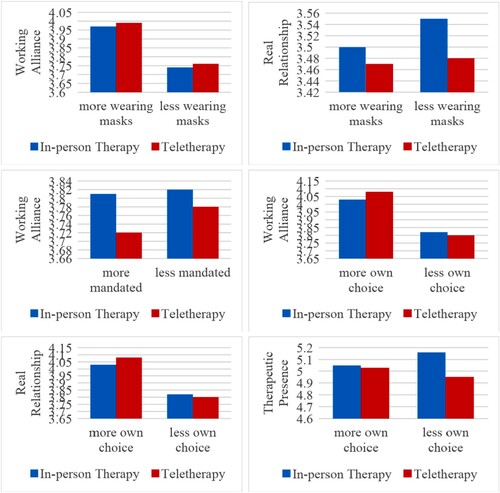

There was no significant main effect of the proportion of time wearing a mask in in-person sessions on the working alliance, however, the interaction between mask wearing and differences in working alliance between in-person versus teletherapy scores was significant (p = .001, η2 = .23). More mask wearing was related to smaller differences in the perceived quality of the working alliance between in-person and teletherapy. For the real relationship, the main effect of mask wearing (p < .001, η2 = .03, d = .4) and the interaction effect of mask wearing were significant (p = .008, η2 = .22). More mask wearing was related to lower real relationship ratings, and to smaller differences in the real relationship between in-person and teletherapy. For therapeutic presence, there was a significant main effect of mask wearing (p = .003, η2 = .02, d = 0.3), but no significant interaction effect of mask wearing on therapeutic presence differences.

The mandated use of teletherapy had no significant main effect on the working alliance, but the interaction between mandated use of teletherapy and the perceived differences in working alliance between in-person and teletherapy was significant (p < .001, η2 = .34). Therapists who conducted teletherapy because it was mandatory reported larger differences in working alliance between in-person and teletherapy. There was no significant main effect or interaction of mandatory teletherapy use for the real relationship, nor for ratings of therapeutic presence.

While the main effect of the extent to which it was the therapists’ choice to conduct teletherapy was not significant for working alliance, the interaction of conducting teletherapy by choice on differences between in-person versus teletherapy scores was significant for the working alliance (p < .001, η2 = .30). For the real relationship, the main effect (p < .001, η2 = .30, d = 1.3) and interaction (p = .007, η2 = .20) were both significant. Similarly, the main effect (p < .001, η2 = .05, d = 0.5) and the interaction (p < .001, η2 = .26) were both significant for therapeutic presence. Therapists who endorsed using teletherapy by their own choice reported relatively larger increases in working alliance and real relationship in teletherapy, and less of a reduction in therapeutic presence in teletherapy scores. Directions of each of these six significant interactions for the three covid-related variables are illustrated in .

Discussion

Teletherapy is an increasingly common practice that had been gaining momentum but was spurred by the pandemic and associated quarantine laws. Although initial research suggested that teletherapy outcomes are similar to those of in-person therapy, very little research has examined the impact of teletherapy on therapeutic relationships, and almost no research has been conducted since the constraints imposed by the pandemic have largely ended. In this study, we used a within-subjects design to compare therapists’ perception of differences in working alliance, real relationships, and therapeutic presence between in-person therapy versus teletherapy. We also examined whether these differences persisted with clinical experience and therapeutic orientation controlled for, and whether features of the therapist, patient, or setting moderated any of the identified relational differences.

Working Alliance

Therapists did not experience significant differences in the quality of their working alliance between in-person sessions and teletherapy sessions. This lack of difference in the experienced quality of the working alliance fits with previous literature from survey studies on therapists’ (and patients’) experiences of teletherapy during the pandemic (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2021; Békés et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). This suggests that although a transition to teletherapy might create discomfort, uncertainty, and professional doubt within the therapist, the actual experience of the collaboration between the patient and therapist might still be very similar to that in in-person therapy. This finding is important for the efficacy of teletherapy, given the robust association of working alliance and treatment outcome (Cataldo et al., Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2022).

However, CBT therapists reported relatively larger differences in their working alliance, whereas process-oriented therapists reported the working alliance to be more similar in both treatment formats. Counterintuitively, CBT therapists reported stronger working alliances in teletherapy relative to in-person therapy. This suggests that there may be some ways in which a videoconferencing format facilitates the working relationship in CBT or promotes the therapists’ effort to develop their collaborative relationship more explicitly. Perhaps videoconferencing lends itself to a discussion about the patient’s real-life circumstances that otherwise receive less attention in a CBT session. For example, in a recent qualitative study, therapists reported that behavioral exposures were aided by the remote format, because exposures could be implemented together with the therapist during the session, while the patient was in their own home (Békés, Aafjes-van Doorn, Roberts, et al., 2022). Obstacles to implementation of homework or exposures might also be more easily identified, when therapists can see the patient’s home surroundings.

Real Relationship

Contrary to our predictions, the real relationship was perceived as lower in teletherapy compared to in-person. Possibly, therapists are more distracted in their remote work, and need to make more effort to be genuinely engaged in the therapeutic work with their patients. Previous survey studies among teletherapists during the pandemic suggested that the real relationship might be higher in teletherapy (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2020; Békés et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). It is possible that the relatively higher real relationship ratings provided by therapists during the pandemic reflected a shared challenge, rather than the change in treatment format per se. Notably, more experienced therapists reported higher real relationship ratings in both treatment formats. When controlling for therapists’ clinical experience, these differences disappeared. This suggests that therapists with fewer years of clinical experience found it harder to have a real and genuine relationship, but this was no different for in-person or remote sessions.

Therapeutic Presence

Perhaps our most significant finding was that therapists reported feeling less present in teletherapy as compared to in-person therapy. This effect was particularly strong for process-oriented therapists, but it applied to CBT therapists as well. Therapists said that they were more prone to boredom or lapses in concentration, and less able to track the subtle nuances of their patient’s experience. This suggests that therapists appeared to find it harder to bring their whole self to the encounter with patients and to be fully in the moment physically, emotionally, cognitively, relationally, and spiritually in teletherapy than in-person (Geller, Citation2017; Geller et al., Citation2010; Geller & Greenberg, Citation2002, Citation2012; Hayes & Vinca, Citation2011, Citation2017). An examination of specific items revealed that the items with the largest effects were reverse coded, suggesting that therapists were more likely to associate the lack of presence with teletherapy. Given the potential technical distractions and concerns about not feeling connected in teletherapy (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., Citation2020), it might not be surprising that the experience of therapeutic presence is negatively affected by a virtual format. The cultivation and maintenance of therapeutic presence in teletherapy has previously been argued to be a precondition to effective therapeutic relationships and a positive working alliance (Geller, Citation2021; Haddouk et al., Citation2018; Hilty et al., Citation2019; Ruble, Citation2021). Future research should focus on how to engender therapeutic presence despite the distance created by a virtual format. Given that more experienced therapists reported higher ratings on therapeutic presence in both treatment formats, training in how to be more present in-session might be important, especially for junior clinicians.

Process-oriented therapists experienced larger reductions in therapeutic presence in teletherapy. Arguably, process-oriented therapists have higher sensitivity and priority for therapeutic presence based on their theoretical approaches (using process as a mechanism of change and using their own emotions/countertransference), and thus may aim for higher levels of therapeutic presence. This means process-oriented therapists may also detect more interruption in therapeutic presence compared to CBT therapists. That said, this difference in therapeutic presence was relatively minor compared to the main effect of therapeutic orientation, in that process-oriented therapists reported much higher levels of therapeutic presence than their CBT-oriented colleagues regardless of treatment format.

Therapists conducting mostly individual therapy reported greater levels of therapeutic presence in general, and larger differences in therapeutic presence in in-person relative to teletherapy (i.e., both higher therapeutic presence in in-person and lower therapeutic presence in teletherapy) than therapists treating couples, families or groups. Arguably, there are already many distractions in couple/family/group treatments. These lower baseline ratings, might mean that the differences in therapeutic presence across in-person/teletherapy modalities may seem less salient. This might suggest that individual therapists are more sensitive to therapeutic presence, and that teletherapy impacts the work less when with more than one patient at a time.

COVID-Related Variables

Therapists who reported that they and their patients wore a mask in a higher proportion of their in-person sessions had higher working alliance ratings than those who did not wear masks in person. This may be due to the fact that a strong working alliance is required to insist on mask wearing, or that sharing the responsibility for wearing masks may aid the collaborative work. Alternatively, those patient-therapist dyads who had stronger working alliances to start with, might have decided to meet in-person to continue the therapeutic work even if it involved wearing a mask. Therapists who wore masks with their patients also reported smaller differences in the working alliance. Wearing a mask and communicating via a screen might be seen as obstacles in connecting. Therapists who had conducted mandated teletherapy rated the working alliance as stronger in in-person therapy than in mandated teletherapy, whereas they reported less difference when teletherapy was not mandated. As might be expected, differences in the real relationship as a function of mask wearing were only observed in in-person therapy. The real relationship was rated as higher by therapists who did not wear masks with their patients. Likewise, therapeutic presence was rated as lower when teletherapy was less their own choice.

This is an interesting juxtaposition between working alliance, real relationship, and therapeutic presence, which are all typically positively correlated. Wearing masks might signal a strong working alliance, whereas not wearing a mask may facilitate a more real relationship. At the same time, the working alliance and real relationship tend to be stronger to the extent that therapists make a choice about how they conduct their work.

Clinical Implications

First, being aware of the differences in the therapeutic relationship in in-person and teletherapy is an important starting point. CBT-oriented therapists might possibly choose to offer (some) teletherapy sessions to help enhance the collaborative relationship with their patients, and the related opportunities of the patient being in their home environment. Second, therapists may want to be cautious to remain therapeutically present in teletherapy. For example, therapists may make practical adjustments in their own professional work space, such as regular work breaks, ample light, removal of physical distractions, and a big video screen. To further increase therapeutic presence in the virtual realm, teletherapists may want to compensate for the reduced therapeutic presence by making non-verbal communications more explicit and less subtle. Discussion of emotions with a patient can also lead to an increased sense of therapeutic presence (Bouchard et al., Citation2011). Lapses in therapeutic presence may not always be avoidable. The fact that therapists themselves perceive lower levels of therapeutic presence in teletherapy may well be noticeable to patients. For example, if there is a noise in the background, the therapist may take time to explain the source, as this knowledge will likely decrease the distraction, build trust and help to regulate the patients’ emotional experience (Alvandi̇, Citation2019; Simpson & Reid, Citation2014). It is likely that patients might also have difficulty being totally present in the therapy session. Being able to role-model how to deal with these potential ruptures in the relationship might become an additional aspect of teletherapy work.

Moreover, in our study more experienced therapists reported higher ratings on all relational variables, in both treatment formats. This suggests the need for further training for and practice by junior clinicians in how to build a therapeutic relationship more generally, regardless of treatment format. It is possible that training in how to establish a therapeutic relationship in in-person sessions might bear benefits to the remote treatment formats as well.

Finally, exploratory moderation findings suggested that, overall, the therapeutic relationship is likely to go better when therapists have some level of agency in choosing whether or not to do teletherapy. At the same time, managing the complexities of teletherapy or safe in-person therapy can potentially be an opportunity to build the working alliance, and this may be a way to reframe mandates or restrictions in the form of therapy to achieve better outcomes.

Limitations and Future Research

This study was unique in that we used a within-subject design in which we asked the same therapists about their experience of in -person and teletherapy. Also, unlike the two other comparison studies that examined therapy techniques and interpersonal skills (Lin et al., Citation2021; Probst et al., Citation2021), therapists completed our survey post-pandemic. This means that a reduction in the therapeutic relationship may be attributed to teletherapy, and is unlikely to have arisen from the high-stress pandemic context (Békés et al., Citation2021). It was thus important to assess the relational experiences in teletherapy as they compare to the same therapists’ experiences of in-person therapy in March-May 2022, during a time where the pandemic no longer impacted our physical and mental health, and professional lives to the same extent.

However, several study limitations can be highlighted. First, our recruitment efforts reflect convenience sampling, without equal subsamples of therapists’ professional training or therapeutic orientation. Most therapists were White, female, and from North America. Future research on subgroups of therapists of different characteristics (e.g., age, socioeconomic status) might be important to consider, as well as the potential moderating effect of different patient populations, treatment types, and session frequency. Therapists who volunteered to participate might also have been especially interested in teletherapy, which possibly biased the results.

Second, this study solely focused on therapist reports and yet therapists and patients may perceive the same session differently. This is relevant, because empirical literature on the working alliance suggests that the patient’s perspective (vs the therapist’s perspective) on the working alliance predicts treatment outcome more strongly. Similarly, patients’ perception of therapeutic presence has a positive impact on session outcome and the therapeutic alliance, whereas therapists’ self-ratings are less reliable (Geller et al., Citation2010). Third, all variables were self-reported responses. This means that the relationship between these variables might have been spuriously inflated. Future research could benefit from using complementary methods to explore therapists’ relational experiences in in-person and teletherapy, for example, by interviewing them to gain their perspective on the therapeutic relationship after a session.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional design, which did not allow to obtain session-by-session ratings of the relational variables, but ratings across sessions for the respective treatment format (in-person; teletherapy). A longitudinal study investigating session by- session ratings of working alliance, real relationship and therapeutic presence, and, in parallel, session-by-session outcomes would provide information about the relative impact of these relational experiences on the outcome in in-person and teletherapy (see e.g., Boswell et al., Citation2010; Fisher et al., Citation2020). Future research would benefit from longer-term follow-up measurements, to examine change over time in these therapists’ experience of the therapeutic relationship variables. Specifically, given that using teletherapy appears to lead to more positive attitudes toward it, therapists may also be able to use the online therapeutic relationship in better ways; or might feel more comfortable with the therapeutic relationship in teletherapy when it is no longer associated with the stressful pandemic time (Messina & Loffler-Stastka, Citation2021).

Finally, we compared teletherapy and in-person therapy as binary categories. Future research should examine the relational quality of “hybrid” treatments, in which teletherapy sessions are integrated within an in-person treatment (Van Daele et al., Citation2020), or patients may receive a combination of in-person and remote sessions based on changing needs over the course of therapy (Yellowlees & Nafiz, Citation2010). This flexibility in how to integrate the use of teletherapy might be particularly important, after the pandemic period of restrictions and societal rules.

Conclusion

We found that therapists reported feeling significantly less present with their patients in teletherapy relative to in-person therapy. They also reported a somewhat lower quality of the real relationship, but no differences in working alliance. Some of these effects may be moderated by factors such as therapeutic orientation, treatment of individuals vs. families/groups, and the types of restrictions that lead to the use of teletherapy. This research has important implications given the increasing use of virtual formats in psychotherapy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.1 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2193299.

References

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K. (2022). The complexity of teletherapy: Not better or worse, but different. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, Advance Online Publication, https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000073

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Békés, V., & Luo, X. (2021). COVID-19 related traumatic distress in psychotherapy patients during the pandemic: The role of attachment, working alliance, and therapeutic agency. Brain Sciences, 11(10), 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11101288

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Békés, V., & Prout, T. A. (2020). Grappling with our therapeutic relationship and professional self-doubt during COVID-19: Will we use video therapy again? Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1773404

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Békés, V., Prout, T. A., & Hoffman, L. (2020). Psychotherapists’ vicarious traumatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S148–S150. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000868

- Alvandi̇, E. O. (2019). Cybertherapogy: A conceptual architecting of presence for counselling via technology. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 6(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.17220/ijpes.2019.01.004

- Békés, V., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Luo, X., Prout, T. A., & Hoffman, L. (2021). Psychotherapists’ challenges with online therapy during COVID-19: Concerns about connectedness predict therapists’ negative view of online therapy and its perceived efficacy over time. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 3036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.705699.

- Békés, V., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Prout, T. A., & Hoffman, L. (2020). Stretching the analytic frame: Analytic therapists’ experiences with remote therapy during COVID-19. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 68(3), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065120939298

- Békés, V., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Roberts, K., Prout, T., & Hoffman, L. (2023). Adjusting to a new reality: Consensual qualitative research on therapists’ experiences with telepsychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23477

- Berger, T. (2017). The therapeutic alliance in internet interventions: A narrative review and suggestions for future research. Psychotherapy Research, 27(5), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1119908

- Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

- Borenstein, L. (2022). Imagination and play in teletherapy with children. American Journal of Play, 14(1), 13–32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1357954.pdf

- Boswell, J. F., Sharpless, B. A., Greenberg, L. S., Heatherington, L., Huppert, J. D., Barber, J. P., … & Castonguay, L. G. (2010). Schools of psychotherapy and the beginnings of a scientific approach. In The Oxford handbook of clinical psychology (pp. 98–127). Oxford.

- Bouchard, S., Dumoulin, S., Michaud, M., & Gougeon, V. (2011). Telepresence experienced in videoconference varies according to emotions involved in videoconference sessions. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 167, 128–132. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brenda-Wiederhold/publication/316495448_Annual_Review_of_CyberTherapy_and_Telemedicine_Evidence-Based_Clinical_Applications_of_Information_Technology/links/590a531aaca272f6580b6f6c/Annual-Review-of-CyberTherapy-and-Telemedicine-Evidence-Based-Clinical-Applications-of-Information-Technology.pdf#page=116

- Boydell, K. M., Hodgins, M., Pignatiello, A., Teshima, J., Edwards, H., & Willis, D. (2014). Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: A scoping review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(2), 87–99. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4032077/pdf/ccap_23_p0087.pdf

- Burgoyne, N., & Cohn, A. S. (2020). Lessons from the transition to relational teletherapy during COVID-19. Family Process, 59(3), 974–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12589

- Cataldo, F., Chang, S., Mendoza, A., & Buchanan, G. (2021). A perspective on client-psychologist relationships in videoconferencing psychotherapy: Literature review. JMIR Mental Health, 8(2), e19004. https://doi.org/10.2196/19004

- Fisher, H., Rafaeli, E., Bar-Kalifa, E., Barber, J. P., Solomonov, N., Peri, T., & Atzil-Slonim, D. (2020). Therapists’ interventions as a predictor of clients’ emotional experience, self-understanding, and treatment outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000377

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Geller, S. (2021). Cultivating online therapeutic presence: Strengthening therapeutic relationships in teletherapy sessions. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(3–4), 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1787348

- Geller, S. M. (2017). A practical guide to cultivating therapeutic presence (pp. xiii, 263). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000025-000

- Geller, S. M. (2019). Therapeutic presence: The foundation for effective emotion-focused therapy. In Clinical handbook of emotion-focused therapy (pp. 129–145). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000112-006

- Geller, S. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Therapeutic presence: Therapists’ experience of presence in the psychotherapy encounter. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 1(1–2), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2002.9688279

- Geller, S. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (2012). Therapeutic presence: A mindful approach to effective therapy (pp. vi, 304). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13485-000

- Geller, S. M., Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2010). Therapist and client perceptions of therapeutic presence: The development of a measure. Psychotherapy Research, 20(5), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2010.495957

- Geller, S. M., & Porges, S. W. (2014). Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(3), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037511

- Gelso, C. (2014). A tripartite model of the therapeutic relationship: Theory, research, and practice. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.845920

- Gelso, C. J. (2002). Real relationship: The “something more” of psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 32(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015531228504

- Gelso, C. J., Kelley, F. A., Fuertes, J. N., Marmarosh, C., Holmes, S. E., Costa, C., & Hancock, G. R. (2005). Measuring the real relationship in psychotherapy: Initial validation of the therapist form. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 640–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.640

- Gelso, C. J., Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., & Markin, R. D. (2018). The real relationship and its role in psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000183

- Haddouk, L., Bouchard, S., Brivio, E., Galimberti, C., & Trognon, A. (2018). Assessing presence in videconference telepsychotherapies: A complementary qualitative study on breaks in telepresence and intersubjectivity co-construction processes. Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 16, 118–123. https://www.interactivemediainstitute.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ARCTT-16.pdf#page=138

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gillaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500352500

- Hayes, J., & Vinca, J. (2011). Therapist presence and its relationship to empathy, session, depth, and symptom reduction. Society for Psychotherapy Research.

- Hayes, J. A., & Vinca, M. (2017). Therapist presence, absence, and extraordinary presence. In How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 85–99). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-006

- Heiden-Rootes, K., Ferber, M., Meyer, D., Zubatsky, M., & Wittenborn, A. (2021). Relational teletherapy experiences of couple and family therapy trainees: “Reading the room,” exhaustion, and the comforts of home. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 47(2), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12486

- Hilty, D. M., Randhawa, K., Maheu, M. M., McKean, A. J. S., & Pantera, R. (2019). Therapeutic relationship of telepsychiatry and telebehavioral health: Ideas from research on telepresence, virtual reality and augmented reality. Psychology and Cognitive Sciences – Open Journal, 5(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.17140/PCSOJ-5-145

- Holmes, C., & Foster, V. (2012). A preliminary comparison study of online and face-to-face counseling: Client perceptions of three factors. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 30(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2012.662848

- Kwok, E. Y. L., Pozniak, K., Cunningham, B. J., & Rosenbaum, P. (2022). Factors influencing the success of telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic and preferences for post-pandemic services: An interview study with clinicians and parents. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12760

- Lin, T., Stone, S. J., Heckman, T. G., & Anderson, T. (2021). Zoom-in to zone-out: Therapists report less therapeutic skill in telepsychology versus face-to-face therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychotherapy, 58(4), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000398

- McCoyd, J. L. M., Curran, L., Candelario, E., & Findley, P. (2022). “There is just a different energy”: Changes in the therapeutic relationship with the telehealth transition. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-022-00844-0

- Mearns, D., & Cooper, M. (2017). Working at relational depth in counselling and psychotherapy. SAGE.

- Messina, I., & Loffler-Stastka, H. (2021). Psychotherapists’ perception of their clinical skills and in-session feelings in live therapy versus online therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A pilot study. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 24(1), 514. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2021.514

- Morland, L. A., Mackintosh, M.-A., Rosen, C. S., Willis, E., Resick, P., Chard, K., & Frueh, B. C. (2015). Telemedicine versus in-person delivery of cognitive processing therapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority trial. Depression and Anxiety, 32(11), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22397

- Norwood, C., Moghaddam, N. G., Malins, S., & Sabin-Farrell, R. (2018). Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(6), 797–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2315

- Pierce, B. S., Perrin, P. B., Tyler, C. M., McKee, G. B., & Watson, J. D. (2021). The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. American Psychologist, 76(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000722

- Prasad, K., McLoughlin, C., Stillman, M., Poplau, S., Goelz, E., Taylor, S., Nankivil, N., Brown, R., Linzer, M., Cappelucci, K., Barbouche, M., & Sinsky, C. A. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine, 35, 100879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879

- Probst, T., Haid, B., Schimböck, W., Reisinger, A., Gasser, M., Eichberger-Heckmann, H., Stippl, P., Jesser, A., Humer, E., Korecka, N., & Pieh, C. (2021). Therapeutic interventions in in-person and remote psychotherapy: Survey with psychotherapists and patients experiencing in-person and remote psychotherapy during COVID-19. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(4), 988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2553

- Rees, C. S., & Stone, S. (2005). Therapeutic alliance in face-to-face versus videoconferenced psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(6), 649–653. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.6.649

- Reynolds, D. J., Stiles, W. B., Bailer, A. J., & Hughes, M. R. (2013). Impact of exchanges and client–therapist alliance in online-text psychotherapy. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(5), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0195

- Richards, P., Simpson, S., Bastiampillai, T., Pietrabissa, G., & Castelnuovo, G. (2018). The impact of technology on therapeutic alliance and engagement in psychotherapy: The therapist’s perspective. Clinical Psychologist, 22(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12102

- Rotger, J. M., & Cabré, V. (2022). Therapeutic alliance in online and face-to-face psychological treatment: Comparative study. JMIR Mental Health, 9(5), e36775. https://doi.org/10.2196/36775

- Ruble, A. E., Romanowicz, M., Bhatt-Mackin, S., Topor, D., & Murray, A. (2021). Teaching the fundamentals of remote psychotherapy to psychiatry residents in the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Psychiatry, 45(5), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-021-01484-1

- Sheperis, D., & Smith, A. (2021). Telehealth best practice: A call for standards of care. Journal of Technology in Counselor Education and Supervision, 1(1), https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0004

- Shklarski, L., Abrams, A., & Bakst, E. (2021). Will we ever again conduct in-person psychotherapy sessions? Factors associated with the decision to provide in-person therapy in the age of COVID-19. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 51(3), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-021-09492-w

- Simpson, S. G., & Reid, C. L. (2014). Therapeutic alliance in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A review. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22(6), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12149

- Smith, K., Moller, N., Cooper, M., Gabriel, L., Roddy, J., & Sheehy, R. (2022). Video counselling and psychotherapy: A critical commentary on the evidence base. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12436

- Solomonov, N., McCarthy, K. S., Gorman, B. S., & Barber, J. P. (2019). The multitheoretical list of therapeutic interventions – 30 items (MULTI-30). Psychotherapy Research, 29(5), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1422216

- Stubbings, D. R., Rees, C. S., Roberts, L. D., & Kane, R. T. (2013). Comparing in-person to videoconference-based cognitive behavioral therapy for mood and anxiety disorders: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(11), e258. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2564

- Thompson, G. (2018). Brain-empowered collaborators: Polyvagal perspectives on the doctor-patient relationships. In S. Porges & D. Dana (Eds.), Clinical applications of the polyvagal theory: The emergence of polyvagal-informed therapies (pp. 127–148). W.W. Norton & Company.

- Thompson-de Benoit, A., & Kramer, U. (2021). Work with emotions in remote psychotherapy in the time of Covid-19: A clinical experience. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(3–4), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1770696

- Udwin, S., Kufferath-Lin, T., Prout, T. A., Hoffman, L., & Rice, T. (2021). Little girl, big feelings: Online child psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 20(4), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2021.1999158

- Van Daele, T., Karekla, M., Kassianos, A. P., Compare, A., Haddouk, L., Salgado, J., Ebert, D. D., Trebbi, G., Bernaerts, S., Van Assche, E., & De Witte, N. A. J. (2020). Recommendations for policy and practice of telepsychotherapy and e-mental health in Europe and beyond. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000218

- Watts, S., Marchand, A., Bouchard, S., Gosselin, P., Langlois, F., Belleville, G., & Dugas, M. J. (2020). Telepsychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Impact on the working alliance. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 208–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000223

- Yellowlees, P., & Nafiz, N. (2010). The psychiatrist-patient relationship of the future: Anytime, anywhere? Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 18(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673221003683952