ABSTRACT

This article considers how public recitation or quotation of Romantic poetry in Aotearoa New Zealand can be read within Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s framework of “settler moves to innocence.” Examining three distinct acts of settler use of Romantic poetry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, featuring Felicia Hemans, Walter Scott, and Robert Burns, the article suggests that we can interpret these moments through the lens of “generations” or the Māori term “whakapapa.” Understanding these apparently isolated moments as part of a process of generating a settler futurity out of Romantic poetry, and foreclosing Indigenous futurities in the process, the essay proposes that some of Romanticism’s cherished lines and authors have underpinned the settler colonial project in Aotearoa in ways that remain both influential and publicly visible to generations of the twenty-first century.

Kia ora tātou. Ko te mea tuatahi, ngā mihi ki Te Ati Awa, ki Ngāti Toa Rangatira, i tō koutou manaakitanga. Ko Nikki Hessell toku ingoa, he Pākehā ahau, nō Whakatāne ahau.Footnote1 I would like to start by acknowledging the tangata whenua (people of the land) of the country I am on, Te Ati Awa and Ngāti Toa Rangatira, and pay my respects to the elders past and present.

My title plays on two phrases that I would like to use as the guiding lines for my essay. One of these requires no gloss for Romanticists: William Blake’s Songs of Innocence, which I am using here as a synonym for Romantic poetry more generally. The other phrase might be somewhat less familiar to some people in Romantic studies. It comes from Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s foundational 2012 article, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” in which they define settler moves to innocence as “those strategies or positionings that attempt to relieve the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege, without having to change much at all” (10). As the structure of my title suggests, I don’t just wish to juxtapose Romanticism and settler thought; I want to entwine them, to think about the way in which Romantic poetry has, at its core, ideas about settler action, awareness, and self-definition, and the ways in which those settler ideas blanket themselves, often unthinkingly, with Romantic poetry.

This essay began life as a keynote for the 2021 Romantic Studies Association of Australasia conference on the theme of “Romantic Generations” and I want to explore this theme by centering my essay in both an abstract idea of generations (in other words, what is it that Romantic poetry generates?) and in a more tangible, corporeal sense (how do we who are settlers imagine ourselves in the generations who descend from the Romantics?). My essay is going to focus on Aotearoa New Zealand partly because, although there is already an extensive body of excellent scholarship about Romanticism and colonization, there is very little that is directly grounded in Aotearoa and its stories. Because of that framing, my essay deals with the settler version of Romanticism, which does not conform to the twentieth- or twenty-first century canon of Romantic literature typified by the “Big Six.” As I have argued elsewhere, the colonial Romantic canon was “lots of Byron, Burns, Scott, and Hemans, some Shelley, no Blake and only a little Keats” (Hessell, “The Indigenous Lyrical Ballads” 253).Footnote2 I am further narrowing my frame to look at the direct quotation or replication of Romantic verse, in part because some of these instances are still tangible presences on the landscape today, unable to be ignored, forgotten, or entirely subsumed into homegrown symbolism, and are thus subject to the strand of twenty-first decolonial work that addresses memorials, statues, and their implications. I am, too, especially interested in the ways that the literal, unchanged, verbatim words of canonical Romantic verse (as opposed to their general sentiments or their mimicking by settler poets) can help us draw tight and unarguable connections between settler identity and this body of poetry and thus gain a deeper understanding of the ideological work Romantic poetry was always doing.

Throughout this essay, I am going to use the Māori word “whakapapa” (genealogy/ancestry) as my key critical term. By way of definition, I offer the explanation given by Ngāpuhi scholars Hana Burgess and Te Kahuratai Painting (and I choose to focus on Ngāpuhi interpretations because much of what I describe in this essay happened on Ngāpuhi whenua [Ngāpuhi’s land]):

Whakapapa is often translated to the Western concept of genealogy, which confines it to the past, and can make it appear to be primarily focused on human relationships of biological descent. However, as Māori, we understand whakapapa as much more expansive. Whakapapa is just as concerned with future generations and how our past and future generations relate to the rest of existence. In knowing something’s whakapapa, the layers that make it up, you can know how it came to be, and how it relates to wider existence. In knowing whakapapa, we can know what will come to be—we can know the future. (209)

The hazard of Hemans

I want to start at Kororāreka, in Te Tai Tokerau, the northern part of Aotearoa, in the 1840s. This is a very important contact zone in the settler colonies at this moment, but it is also where my own identity as a Pākehā (settler of European descent in New Zealand) begins, where the first generations of my family arrive in Aotearoa, so it is a place from which I feel I can speak. In February 1840, rangatira Māori (Māori chiefs) signed the Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown. In the English version of the text, Māori cede sovereignty but retain the right to their lands, forests, and fisheries. In the Māori text, Māori cede kawanatanga (that is, governance) but retain tino rangatiratanga or sovereignty.Footnote3 The document was meant to be the beginning of a fruitful relationship, but it quickly became clear to Māori in the North that the ideals of partnership and collaboration, especially around questions of trade, were not being met.Footnote4

In mid-1844, and then twice more in the early months of 1845, Hone Heke, the first person to sign Te Tiriti (the Māori text of the treaty), chopped down the British flagstaff at Kororāreka, leading the colonial officials to fortify the flagstaff against further attack. Determined to chop it down a fourth time, Hone Heke and his allies hatched a plan. Another local rangatira, Kawiti, and his men would create a diversion, drawing the guards away from the fortification to allow Heke to attack it again.

On 11 March 1845, Kawiti and his men engaged in a skirmish with some of the men from the HMS Hazard at Christ Church, leading the garrison to come to the sailors’ aid, and giving Heke the opportunity to successfully chop down the flagstaff. But at some point, in what appears to have been an accident, the town’s gunpowder magazine exploded, causing panic and an order to evacuate the entire settler population. In retaliation for what they imagined was a Māori attack on the town, the HMS Hazard began to bombard Kororāreka. Thirteen Māori were killed and twenty-eight wounded, while Pākehā losses were twenty dead and twenty-three wounded. It was the opening battle of the Northern War.

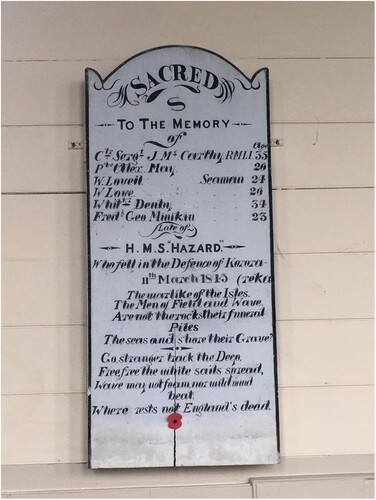

Figure 1. Plaque on the wall of Christ Church, Kororāreka (Russell), Aotearoa New Zealand. Photograph courtesy of the author.

What is the significance of the siege of Kororāreka for Romantic studies? It comes back to that churchyard, where Kawiti’s men encountered the sailors from the HMS Hazard. If you visit Christ Church today, in the town that we now call Russell, you will see a memorial on the wall inside the church to the casualties from the Hazard (see ). Under the names of the six sailors who perished are the final two stanzas of Felicia Hemans’s poem “England’s Dead”:

The warlike of the Isles,

The Men of Field and Wave!

Are not the rocks their funeral Piles

The seas and shores their Grave?

Go, stranger track the Deep,

Free, free the white sail spread,

Wave may not foam, nor wild wind beat,

Where rest not England’s dead.Footnote5

In many ways, this is a very obvious poem for settlers to choose to commemorate their dead in nineteenth-century Aotearoa New Zealand. As Jason R. Rudy has pointed out in his masterful study Imagined Homelands: British Poetry in the Colonies, Hemans’s popularity in the Antipodes meant that “it would have been odd if emigrants in the … colony had not turned to [her]” (46). But the sense of Hemans’s universal applicability to settler contexts should not prevent us from noticing the very particular work that her poems do in their new homes and the way in which that apparent “universality” is often a by-product of settler deployments, rather than a feature of the verses themselves.

This tension between what Hemans’s poem actually says and what it is made to stand for in Kororāreka can be seen in the question of memorialization itself. The whole poem is driven by the opening stanza’s questioning rhetoric:

Sons of the Ocean Isle!

Where sleep your mighty dead?

Show me what high and stately pile

Is reared o’er Glory’s bed. (1–4)

Into this climate of uncertainty, we can think about the work that the Kororāreka memorial does alongside, around, and against the poem itself. Its very existence suggests that no, the rocks will not serve as a funeral pile, nor the seas and shores the graves of the men from the HMS Hazard. A further layer of memorialization is required, in which Hemans’s very lines about the absence of markers will be put to work as markers.

What is it that they mark, then? “England’s Dead,” certainly, since the sailors on the HMS Hazard would have seen themselves as English or British and could easily be incorporated into the story of global heroism and tragedy that Hemans wishes to tell. “England’s Dead,” too, in the sense that this is explicitly not a complete or inclusive memorial to the events and casualties of 11 March 1845; none of the thirteen Māori killed that day are named here. The lines of poetry themselves bear no hint of the geographical place in which they now find themselves; in fact, there is no straightforward reference to the Pacific in Hemans’s poem at all. “England’s Dead” directly names or evokes a wide range of imperial or global settings: “Egypt,” the “Ganges,” “Columbia” and the “Pyrenees” (9, 19, 27, 34) are all named directly, while “the frozen deep” (41) and “the ice-fields” (43) point to polar locations. But there is no such positive link in the poem to a British presence in Aotearoa, or Australia, or the Pacific Islands.

The memorial at Kororāreka is thus not picking up on any stated claim in “England’s Dead” to Britain’s Pacific holdings or territories. What it is doing, instead, is forging that claim out of the existing imperial materials of the poem and stamping it on the wall. It co-opts Aotearoa to Hemans’s vision, using but extending the language of the poem to claim territories over which its authority was actually very tenuous in that moment. Poetry here is an augmentation of the legal documents that underpinned the British Empire, such as the Treaty of Waitangi, its language performing a declaration of sovereign control similar to those performed via treaty and statute. It pushes out the geographical boundaries of Hemans’s poem at the same time as it pushes out the boundaries of Britain’s empire; or more accurately, the extension of one set of those boundaries facilitates the extension of the other. Poetry here is a flag, staked in the ground, not at all unlike the flag that Hone Heke rightly concluded needed to be chopped down if Māori sovereignty was to hold, the very act that led to the deaths that Hemans’s lines now mark.

This process of using poetry in the cause of settler colonialism is made possible, in part, by what we might call the liquidity of “England’s Dead.” If the Pacific is never directly mentioned, in other words, it nevertheless fills in the formless spaces of the poem like water. As the two stanzas highlighted in the HMS Hazard memorial testify, Hemans’s imperial imaginary is oceanic, constructed out of waves, seas, shores, and foam, tracked across the deep and measured in islands. When Hemans wrote the poem in 1822, Britain’s colonial ambitions in the South Pacific were very amorphous. By 1845, and the siege of Kororāreka, they had taken a more obvious shape. The liquidity of the poem, then, the watery way in which it imagines Britain’s naval power as the driving force that produces these global tombs, is easily adapted to the new realities or the projected fantasies of post-Treaty of Waitangi Aotearoa.

This, then, is my first example of a Song of Settler Moves to Innocence. Tuck and Yang’s phrase describes modern settlers’ attempts to avoid feelings of guilt or responsibility and might seem like an imperfect fit for a much older poem, written at a moment when settlers were considerably less likely to experience those feelings. But not only does the poem do some of this emotional work at its moment of composition, by imagining the losses and tragedies of imperial violence as wholly experienced by the colonizing side, its ongoing presence at Russell locates it within not only its historical moment but among modern settler experiences and feelings. At the memorial at Christ Church, the oldest church in New Zealand and a significant tourist attraction in the North, we (Pākehā settlers) are not asked to change at all: our poetry, our songs, can be adapted to this space, regardless of whether or not they say anything about the place and the land on which they are now inscribed. They require no editing at all. The sailors of the HMS Hazard are likewise cast as blameless, the innocent victims of imperial power and/or Indigenous violence, martyrs to the settler cause. We are not required to give up anything. In fact, more significantly than that, we not only retain everything, we generate something, to return to the theme of this issue: a narrative of settler pasts, presents, and futures that can take hold in Aotearoa. Lines of whakapapa are disrupted here, in the families of the men who died, but a national story, grounded in Romantic poetry, is projected out into the future. If it seems far-fetched to think of a nineteenth-century memorial as doing this kind of work for settler thought, it might be worth noting that, for twenty-first century visitors to Christ Church, there is now an ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) poppy attached to this memorial, linking the twentieth-century world wars and especially Gallipoli, an absolutely critical event in settler identity in this part of the world, one that the men of the Hazard could not have begun to imagine, to the memorialization of their deaths.

Fast forward twenty years from the siege of Kororāreka to the 1860s, and the Reverend James Buller, a Wesleyan minister, is giving a lecture to the Young Men’s Christian Association, a lecture later reprinted in the Auckland newspaper the Daily Southern Cross. Like a great number of nineteenth-century lecturers, ministers, journalists, and pamphleteers in Aotearoa, Buller peppered his talk with quotations from Romantic poetry, especially from the major figures in the settler Romantic canon. I am choosing to focus on this lecture as an example because it is paradigmatic of the ways in which such quotation was used to bolster Pākehā claims to sovereignty and control of land, and to tell a particular story about both the history of the colony and its future. Buller’s talk is entitled “Our New Zealand Home,” and in it, he uses another very well-known Hemans poem, “The Homes of England,” to explain his theme, quoting these lines:

The free fair homes of England!

Long, long in hut and hall

May hearts of native proof be rear’d,

To guard each hallow’d wall;

And green for ever be the groves,

And bright the flowery rod,

Where first the child’s glad spirit loves

Its country and its God.Footnote6

So we embalm in our filial affectionate remembrance, the home of our fathers and our early days, while we enter upon our new home in this Southern isle—a home, I may say, of which we have no reason to be ashamed—a home that will hereafter rival the glories of that which we have left—a home, we verily believe, which is to be “the Britain of the South.” (5)

These fantasies can mean the adoption of Indigenous practices and knowledge, but more, refer to those narratives in the settler colonial imagination in which the Native (understanding that he is becoming extinct) hands over his land, his claim to the land, his very Indian-ness to the settler for safe-keeping. This is a fantasy that is invested in a settler futurity and dependent on the foreclosure of an Indigenous futurity. (14)

While to a twenty-first-century audience, the term “native” suggests something close to the categorization of the Indigenous peoples of the settler colonies, Hemans uses the term in a way that was entirely consistent with nineteenth-century British usage as well as being entirely logical on its own terms: the residents of the homes of England are, naturally, “native” to England. Buller’s use of Hemans’s lines, however, moves this definition into the territory of fantasizing adoption that Tuck and Yang trace. By simultaneously “embalming” England as home and relocating Hemans’s homes to Aotearoa, Buller suggests that “hearts of native proof” can and are being reared in the settler colony. The children born in Aotearoa and raised, like Hemans’s imagined child, to possess a “glad spirit [that] loves / Its country and its God” (39–40), are, via the poetry, fantasized as “native” to their new land. In Hemans’s poem, nativeness is unproblematic, justified, and peaceful. In Buller’s usage, however, it becomes a tool of displacement, in which actual native peoples are superseded by a newly “native” settler population. It is, in fact, the very unproblematic and simple nature of Hemans’s lines in their original British context that facilitates this process: a poem that states a straightforward truth about belonging, nativity, citizenship, and patriotic values can become, once it is unmoored from its original author and her moment of composition, a potent weapon of dispossession. It is, as Tuck and Yang put it, “a fantasy that is invested in a settler futurity and dependent on the foreclosure of an Indigenous futurity.” It is a very explicit settler move to innocence, one designed in part to avoid feeling “ashamed” of a new identity, in which the term “native” and its specific definitions can glide into settler life and self-imagining.

Once again, this is an example that is about Romantic generations. It is generative of a settler future, conditional on Indigenous extermination, and it foregrounds the other side of the whakapapa imagined in Hemans’s “England’s Dead” and on the walls of Christ Church: some settlers will die in the colonies, but other children will be born there. Whakapapa Pākehā will gradually, peacefully or not, displace whakapapa Māori, as new generations replace the old.

Walter Scott on native land

Hemans was not Buller’s only poetic source for notions of the “native” in his lecture that day, however. Early on in his talk, he recited a passage of Walter Scott’s The Lay of the Last Minstrel:

Breathes there a man with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

“This is my own, my native land;”

Whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d,

As home his footsteps he hath turned,

From wandering on a foreign strand?

If such there breathe, go mark him well:

For him no minstrel’s raptures swell;

High though his title, proud his name,

Boundless his wealth as soul can claim,

Despite these titles, power, and pelf,

The wretch, concentred all in self,

Living, shall forfeit fair renown,

And, doubly dying, shall go down

To the vile dust, from whence he sprung,

Unwept, unhonoured, and unsung. (Canto 6, lines 1-16)

In Buller’s formation, Scott’s lines, and especially his formulation of what it means to be “native,” help to explain Buller’s own sense of connection to Aotearoa. Part of how Buller creates this native-settler identity is to stress the “newness” of the country:

It is in every sense a new home—new, comparatively, in its geological formations. The only fossil it contains, if fossil it can be called, is the gigantic frame of the extinct moa. Its strata of coal have not had time to mature. It is new as the abode of humanity. The Maoris [sic], according to their traditions, landed on its shores in the first expedition, not far from where we are assembled, about 500 years ago; and it does not appear that they found it occupied by any prior race. It is newer still as the abode of civilisation and the field of European colonisation. Some of us are old enough to remember when New Zealand was all but a terra incognita—when the British sailor touched in peril on its coasts—when it was a word of terror in our far-off early home. (5)

There is a darker parallel process at work in colonization too, of course. It is not simply enough to occupy the rhetorical and political space of Indigenous peoples: settler cultures also enacted and warmly embraced the assimilation and, in many instances, the extermination of Indigenous populations, creating a literal generational replacement to accompany the conceptual and classificatory one. It is this particular sense of the future, one in which Indigenous peoples are completely absorbed or replaced, that Buller wishes to speak about. Romantic poetry had a role to play in that darker process for Buller as well. As he put it in his lecture that day, “I have spoken in fragments of the past; I have referred to the present; but what of the future? . . . The native question is far from settled . . . The Maori will not soon be blotted out of being. The ‘Lay of the Last Maori’ will be sung, but not yet” (5).

Having quoted lines from The Lay of the Last Minstrel earlier in his lecture, Buller presumably had this title in his mind for the grim play on words here. But I want to spend some time thinking about why Scott seemed apt to Buller’s argument. Scott’s usefulness in the colonial world has been expertly explored by Ann Rigney in her 2012 book, The Afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the Move. Focusing largely on the novels, Rigney examines what she calls “Scott’s particular strength as a memory-maker” for colonial populations, someone whose work “was not tied down to any one place or community, but could operate in both national and transnational frameworks” (13–14). In Rigney’s reading, Scott’s works provide a sense of a common past that could be used to generate a meaningful and unified present. Some of that common past is available in the section of Buller’s speech where he lists some key events in New Zealand history, using the repetition of the phrase “we remember” to structure his list. The siege of Kororāreka is, needless to say, on Buller’s list: “We remember … the fall of the flagstaff at the Bay of Islands by the turbulent chief Heke—the war that followed, wherein, so many of our brave men perished—the sack of Kororarika [sic]” (5). The memory-making and the focus on the past is no doubt important, but I would stretch Rigney’s interpretation further, and say that the ultimate goal of these repurposings of Scott, like the repurposing of Hemans, is to put these past and present imaginings to work for a settler future, one predicated on some degree of assimilation or eradication, not simply to create an immediate and usable national identity. This blending of past, present, and future is available in Scott’s novels but is even more apparent in a poem like The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

We can apply White Earth Band Ojibwe scholar Jean O’Brien’s notion of “lasting” to this utilization of Scott’s Lay of the Last Minstrel too. Settler narratives, O’Brien notes, are often focused on the “last” member of a native people, conjuring into existence a sentimental sympathy alongside a genocidal determinism, in which Indigenous peoples will not be allowed to be modern (105–44). A settler future requires that there will one day be a last Indigenous person, a final generation, as Buller imagines here. Any sense of guilt or responsibility for that extermination is foreclosed by a parallel sense of inevitability and thus bloodlessness in order to protect settler feelings. Settlers will be allowed to continue regenerating, in Buller’s formulation, to have a whakapapa that will replace whakapapa Māori. And in the course of creating that settler future, pieces of Romantic poetry are starting to take on a whakapapa of their own, regenerating, replicating, and being passed around in newly colonized lands.

#Burnsmustfall

My final example is titled in a somewhat facetious fashion: just to be clear, I do not really think that the four Robert Burns statues in Aotearoa need to come down, or, to put it more accurately, the Burns statues are a long way down the list of settler monuments that should be removed. But I do want to spend a moment tracking the way in which these statues of Burns and, more significantly, the lines of poetry they incorporate, are part of the whakapapa of Romantic poetry in Aotearoa.

The four statues not only show Burns in four quite different poses and personae; they also take four different approaches to the poetry. The 1921 Auckland statue has no lines from Burns, just an inscription reading “To the immortal memory of Robert Burns, 1759–1796. The peasant bard of Scotland, the strong advocate of universal freedom and the brotherhood of man.” The 1887 Dunedin statue also has no lines but shows Burns holding a manuscript of the poem “To Mary in Heaven.”

The statues in the smaller southern centers take a different approach, engraving some of Burns’s own lines onto the monuments themselves. The 1913 statue in Timaru first establishes Burns’s role in a global imaginary of the British empire by quoting this description from Thomas Carlyle: “The largest soul of all the British lands,” followed by the famous couplet from “A man’s a Man”: “The rank is but the guinea stamp / The Man’s the cowd for a’ that.” Here we can see Burns emerging as a figure of Pākehā identity within a wider imperial and settler-colonial context, in which Timaru is envisaged as part of “the British lands,” but also the emergence of his poetry as a marker of a key Pākehā value, the quest for an often illusory state of egalitarianism. The poetry is important here for providing ballast to a post-World War I notion of Aotearoa as a fair place, where everyone is assumed to have an equal opportunity to thrive. The Hokitika statue goes even further with the poetry, including two couplets from “The Cotter’s Saturday Night”:

From scenes like these, old Scotia’s grandeur springs,

That makes her lov’d at home, rever’d abroad:

Princes and lords are but the breath of kings,

“An honest man’s the noblest work of God.”Footnote7

It goes without saying that all of these statues are built on Māori land. But I want to outline here a little of the story of the particular land on which those two poetic South Island monuments stand. The Hokitika statue stands in Cass Square, named after Thomas Cass, in his time a well-known figure as the Chief Surveyor for Canterbury, although hardly remembered today. The Timaru statue, meanwhile, is on land reserved for botanical gardens by Cass in his capacity as Chief Surveyor. In both cases, the statues were erected long after Cass’s death but in memory of the work he had undertaken to secure this land for Pākehā settlement. Cass is a very minor figure in Pākehā history; I doubt that many of the good people of Hokitika know for whom Cass Square is named. But I want to comment briefly on the way in which Cass’s legacy continues the whakapapa of Romantic poetry in Aotearoa. It is not just the case that, in Timaru and Hokitika, we have Burns’s poetic lines used on lands surveyed and claimed by, and in some cases now named after, Thomas Cass, although that is one of the ways in which Romantic verse interacts with generations of Pākehā settlers. It is also that Cass himself was at the event with which I began this essay: the siege of Kororāreka. He surveyed the town of Kororāreka, was serving as chief mate on the brig the Victoria on the day of the siege, and went on to serve in the British forces against Hone Heke and his allies in what came to be known colloquially as “Heke’s war.” One startlingly contemporary image, George Thomas Clayton’s sketch of the town on the morning of the siege, gives a sense of how closely Cass’s history is entwined with the history of the Hazard and Kororāreka; the HMS Hazard is pictured on the left-hand side of the image, with the HMS Victoria in the middle, the flagstaff that Heke would attack on the hill to the left, and Christ Church in the settlement at the center of the picture.

These settler stories interact and spool down the generations, then. More significantly, Romantic poetry is at the heart of the settler storywork that is going on in the Hemans monument at Kororāreka, and then in Buller’s lecture remembering Kororāreka and weaving in Hemans and Scott, and then on the Burns monuments built on land surveyed for settler annexation by a Kororāreka veteran. Romantic poetry is part of the Pākehā story, operationalized at key moments of violence, memorialization, and acquisition, woven into the stories we tell ourselves about the generations that have passed. It is still present on the land, in the statues, memorials, and stories that twenty-first century towns and cities preserve. And, as the Cherokee writer Thomas King has put it, “the truth about stories is that that’s all we are” (153).

Claiming bad kin

What is our responsibility as Romanticists, then, especially if we are settlers living in the settler colonies? How do we account for the Romantic poetry, much of which we teach, research, and cherish, that sits at the heart of some of the violent acquisitiveness of former generations and thus the inherited wealth of the current generations, ourselves included? To help talk through this idea, I turn to the work of feminist philosopher Alexis Shotwell and her notion of “claiming bad kin.” As Shotwell puts it: “settlers make terrible kin not because of who particular people are, but because settler colonialism is a structure based on betraying relationality, both historically and in the present” (9). Shotwell argues, in juxtaposition to Black scholar Christina Sharpe’s call for white people to “Lose Your Kin,” that we have to be prepared not to disavow, but to claim bad kin, to claim, among other figures, the racist founders of our states. For me, then, the men of the Hazard are my kin; James Buller and Thomas Cass are my kin. So too, sadly, are the people who desecrated a pouwhenua (land marker) in the form of a tīpuna (ancestor) just a few weeks before I gave the talk on which this essay is based, at a place called Cass’s Bay, named, again, after Thomas Cass (Burrows). Instead of our statues, this is what falls.

But how might we extend the idea of “claiming bad kin” into the Romantic canon and our research and teaching in Romantic studies? I think we need to acknowledge the relationality that binds a lot of settler scholars to Romanticism and the Romantic period. It does not surprise me at all that the academic study of Romantic literature has flourished in the four main British settler colonies. Those of us who are settler scholars in those colonies are deeply embedded in the kinship networks of the Romantic period, the networks that led to settler colonialism in Australia and Aotearoa and that fueled the existing paradigm of settler colonialism in North America after 1776. It is no surprise that we have grown to love the two generations of British writers who lived at and chronicled the time that our settler-colonial nation states emerged. But loving them is not the same as ignoring the racist uses to which their words were put, or, indeed, the racism that underpins some of the poetry. It means being alert to the ways in which moves to innocence are framed by this poetry, a seamless naturalization of our right to be on these lands, and the projection of a settler future cast as memorialization but really a kind of poetic aspiration to nativeness and to place. These deployments of Romantic poetry cross generations and are themselves generative, providing a literary text for a historical process, creating the stories on which settler identity can then be based.

I return here to Burgess and Painting’s formulation of whakapapa to comprehend our responsibilities:

In being a part of this infinitely expanding web of existence, everything we do lays down whakapapa. We are never isolated, we are always in relation, thus always laying down whakapapa. Knowing this, we understand that there is no neutral action, there is no action disconnected from our tūpuna (ancestors) and mokopuna (grandchildren/future generations). Therefore, just as isolation and emptiness are fallacies, so too is the notion of inaction. In ontologically privileging relationships, everything is understood in terms of its relations, and all relationships emerge through whakapapa. (218)

In my opening land acknowledgment, I followed the formula that I have learnt from listening to settler Australians, in which we thank the generations past and present. That sophisticated knowledge of the simultaneous existence and purpose of generations brings me back to the churchyard at Kororāreka. The memorial to the men on the Hazard sits on the wall of the church, but that is not the only place that it sits. Outside, in the graveyard, among generations of the dead, it is replicated, not painted on wood but carved in stone. The wooden plaque inside the church was created very soon after the siege of Kororāreka and originally marked the graves outside, but, after fifty years of deterioration, it was moved inside, and this new stone monument put up to replace it in the churchyard. Somehow, Romanticism finds a way to multiply, spread out, claim space, convert itself from wood to stone, from arrival to resident, from settler to native. Hemans’s poem is inside, it is outside, it names the dead and it lies alongside them, it is itself a replication, and it has replicated itself. It has become, like Scott’s works, like Burns’s, part of the Romantic generations of Aotearoa. It has become a song of a settler move to innocence (see ).

Notes

1 Hello everyone. First, I greet Te Ati Awa and Ngāti Toa Rangatira, and thank them for the hospitality. My name is Nikki Hessell, I am a Pākehā [settler of European descent in New Zealand] and I was born in the town of Whakatāne (my translation).

2 For my work on the significance of this settler version of the Romantic canon for Indigenous peoples in the colonies, see my Romantic Literature and the Colonised World and my Sensitive Negotiations.

3 A comparison between the English version signed in 1840 and an English translation of the Māori text can be found in Belgrave, Kawharu and Williams (388–93).

4 See for example Orange’s “Treaty of Waitangi—The First Decades.”

5 Hemans’s lines are reproduced here as they appear in on the wall of the church, both in terms of content and typographically. With some small differences, they are lines 49–56 of the longer poem, which can be found in Hemans’s Poetical Works (218). The most significant difference is “beat” in place of “sweep.”

6 Hemans’s lines are reproduced here as they appear in Buller’s text; they are lines 33–40 of the longer poem, which can be found in Hemans’s Poetical Works (318). Buller (or his editor) transcribes Hemans’s “sod” as “rod” in line 38.

7 These lines are transcribed as they appear on the statue (lines 163–66 of the poem).

References

- Belgrave, Michael, Merata Kawharu, and David Williams, ed. Waitangi Revisited: Perspectives of the Treaty of Waitangi. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

- Buller, James. “Our New Zealand Home.” Daily Southern Cross (15 June 1867): 5. Print.

- Burgess, Hana, and Te Kahuratai Painting. “Onamata, Anamata: A Whakapapa Perspective of Māori Futurisms.” Whose Futures? Ed. Anna-Maria Murtola and Shannon Walsh. Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland: Economic and Social Research Aotearoa, 2020. 207–33. Print.

- Burrows, Matt. “Pouwhenua Smashed to Pieces in Lyttleton, Christchurch, Prompting Police Investigation.” Newshub (8 Nov. 2021). Web.

- Hemans, Felicia. The Poetical Works of Mrs. Felicia Hemans: Complete in One Volume. Philadelphia: Thomas T. Ash, 1836. Print.

- Hessell, Nikki. “The Indigenous Lyrical Ballads.” The Cambridge Companion to the ‘Lyrical Ballads.’ Ed. Sally Bushell. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2020. 253–68. Print.

- Hessell, Nikki. Romantic Literature and the Colonised World: Lessons from Indigenous Translations. New York: Palgrave, 2018. Print.

- Hessell, Nikki. Sensitive Negotiations: Indigenous Diplomacy and British Romantic Poetry. New York: SUNY P, 2021. Print.

- King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: Anansi, 2003. Print.

- O’Brien, Jean M. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota P, 2010. Print.

- Orange, Claudia. “Treaty of Waitangi—The First Decades after the Treaty—1840 to 1860.” Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Web. 30 June 2022.

- Rigney, Ann. The Afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the Move. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

- Rudy, Jason R. Imagined Homelands: British Poetry in the Colonies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2017. Print.

- Scott, Sir Walter. The Lay of the Last Minstrel. Edinburgh: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1805. Print.

- Sharp, Sarah. “Exporting ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’: Robert Burns, Scottish Romantic Nationalism and Colonial Settler Identity.” Romanticism 25.1 (2019): 81–89. Print.

- Sharpe, Christina. “Lose Your Kin.” The New Inquiry 16 Nov. 2016. Web.

- Shotwell, Alexis. “Claiming Bad Kin: Solidarity from Complicit Locations.” The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: Bearing (2019): 8-10. Web.

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1.1 (2012): 1–40. Print.

- Wolfson, Susan J., ed. Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Letters, Reception Materials. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.