Abstract

A 2018 California law requires local governments to affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH) in their General Plan’s housing element. This paper examines how eight municipalities reacted to this requirement in three areas of their 2021 plans: the analysis of fair housing issues, proposed fair housing programs, and the location of sites identified for low-income housing development. We consider whether these cities’ over 200 fair housing programs are meaningful actions by evaluating their potential impact, and measure the distribution of proposed sites for new low-income housing across neighborhoods. The cities created many new programs in response to the mandate; however, most programs do not meaningfully advance fair housing goals. Moreover, most cities do not modify land-use plans to allow affordable housing in affluent neighborhoods. Additionally, we find a mismatch in the plans. The affluent, majority-white cities that developed more meaningful fair housing programs continued to concentrate sites for affordable housing in their least affluent neighborhoods. Our analysis of potential program impact allows us to identify AFFH oversight challenges and make recommendations for AFFH guidelines. We focus on California, but the research is relevant to federal AFFH implementation and raises questions about how to best advance fair housing goals.

Introduction

Local government recalcitrance has long stymied efforts by federal and state agencies seeking to make progress toward important social goals, especially fair housing. Aggressive resistance to the implementation of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) mandate of the 1968 Fair Housing Act led to it being essentially unenforced for over 40 years (Hannah-Jones, Citation2015). In 2015, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) created a final AFFH rule that required grantees, including local governments, to analyze fair housing issues and develop meaningful actions to address them.

Existing scholarship assesses the 2015 rule positively compared to previous AFFH implementation efforts (Steil & Kelly, Citation2019a), yet research to date has not questioned, to our knowledge, whether programs in analyses of fair housing (AFH) represent meaningful action as required by fair housing law. Rather, research has focused on whether grantees have completed AFH and proposed programs as required by HUD (Steil & Kelly, Citation2019a), the fair housing goals AFH emphasize (Elder et al., Citation2022), and how HUD could better oversee AFFH analysis and actions by grantees (Haberle et al., Citation2020).

In California, a 2018 state law brought the federal AFFH requirement into the state’s existing planning mandate system. This creates new potential for progress because the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) plays a more direct role in land-use planning than HUD (Williams, Citation2019). Every eight years, local governments in California must update their general plan’s housing element, which is not only an analysis of constraints to housing development but also includes a list of specific parcels that can accommodate new housing, including subsidized housing for low-income households. The deadline for finalized and compliant housing elements for Southern California jurisdictions was October 2021.

In this paper, we describe how local governments in Southern California reacted to the new requirement to analyze and take meaningful action on fair housing challenges in their housing plans by answering four questions. First, did cities analyze fair housing problems according to the guidelines? Second, what kinds of programs did cities create in response to the fair housing law? Third, did these new housing programs represent meaningful actions toward fair housing goals? Fourth, did cities propose land-use plans that lay the groundwork for the AFFH goal of integrated and balanced neighborhoods?

We answer these questions by analyzing recently completed housing elements for eight municipalities in Southern California, which we selected to represent a range of segregation levels across a diverse set of contexts. We assess the quality of their AFH, scrutinize the roughly 230 programs in their housing elements, and quantify the spatial distribution of both the cities’ existing multi-family zoning and their plans for new housing development with respect to neighborhood incomes and racial/ethnic homogeneity. Finally, we explore the proposition that more segregated cities created housing plans with more meaningful programs.

Our assessment yields three primary findings. First, the AFFH mandate spurred cities in California to create many new programs (over half of these cities’ programs are new). Yet our analysis suggests that most of these programs do not represent meaningful action because they have long or unclear timelines, ambiguous objectives, and/or represent minimal change to rules or limited commitment of municipal resources or staff time.Footnote1 Second, we find that most cities do not plan to substantially change land-use rules in a way that would integrate neighborhoods.Footnote2 Most cities identify potential sites for low-income housing in their less affluent neighborhoods and near existing multi-family zones, thus exacerbating status quo land-use patterns.

Finally, we find that the cities with a higher share of white, high-income residents created more meaningful programs, yet failed to create land-use plans that would enable neighborhood integration, by race or socioeconomic status. On the other hand, two of the less white, less affluent places did advance fair housing goals in their land-use plans. This mismatch between AFFH challenges and actions raises questions about the current AFFH process. High-resource places have greater capacity to develop more complex plans but not make changes necessary to achieve the law’s goals.

Fair housing law has multiple goals, and achieving them will require actions in multiple arenas (e.g., land-use reform, housing subsidies, investment in public goods, and legal support) at all levels of government. This paper focuses on local housing development plans and AFFH programs. These plans must address all fair housing goals, but we consider land-use regulation to be the most consequential tool that local governments control (Menendian, Citation2017) and land-use reform is a necessary—if insufficient—component of fair housing efforts. Local governments could use locally generated revenues to fund housing programs, but have not traditionally done so. Neither have local governments taken on major roles in anti-discrimination efforts. We consider local action essential for achieving fair housing goals, and the recognition of the reality of local action—primarily land-use regulation, some funding for infrastructure, and limited funding for housing programs—frames our evaluation.

Background and Related Literature on AFFH

When California adopted the AFFH requirement in 2018 through AB 686, the state copied the procedural approach of HUD’s 2015 rule. That final rule has four broad goals:

addressing significant disparities in housing needs and in access to opportunity, replacing segregated living patterns with truly integrated and balanced living patterns, transforming racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty into areas of opportunity, and fostering and maintaining compliance with civil rights and fair housing laws. (Department of Housing and Urban Development, Citation2015, p. 5)

Research on the Implementation of the 2015 AFFH Rule

Research on the impact of the 2015 AFFH rule found that local AFH were a substantial improvement over the previous HUD-mandated Analyses of Impediments (AIs) of the 1990s, which carried low expectations for specificity and action (Silverman et al., Citation2013; Steil & Kelly, Citation2019a). A 2019 special issue of Housing Policy Debate on fair housing shows that scholars and policy experts were optimistic about the potential influence of the 2015 rule, even if they recognized its limitations (for a review, see Jargowsky et al., Citation2019).

Since the implementation of the final rule in 2015, scholars have evaluated different aspects of local AFH; however we found no studies that assess their potential impact. The closest is Steil and Kelly (Citation2019b), who analyze AFFH programs in 30 municipalities. They quantify the number of programs that are new and have measurable objectives, and assess the improvement in AFFH implementation based on the increase in the share of programs with these features compared to previous AIs in those same municipalities.

We expand on the methodological approach of Steil and Kelly (Citation2019b) by evaluating not only whether programs are new, have measurable objectives, and propose concrete timelines, but also their potential for making progress on AFFH goals. In other words, are they meaningful actions? As we will show in California, cities can create new AFFH programs with concrete objectives and timelines that are nonetheless unlikely to make meaningful progress toward fair housing goals. For example, a clear commitment to update a city website with information for first-time homebuyers within one year has limited potential to create integrated and balanced neighborhoods or reduce disparities in access to opportunities despite having clear objectives and timeline.

Other research efforts focus on reviewing and critiquing AFFH implementation by HUD—for example, O’Regan and Zimmerman (Citation2019), who describe the 2015 rule in comparison to previous HUD actions, but do not review AFH—or analyzing specific aspects of AFH. Elder et al. (Citation2022), for example, review the goals of 40 AFH, focusing on the extent to which homeownership is prioritized. A publication by the Poverty and Race Research Action Council (Haberle et al., Citation2020) synthesizes their own advocacy work and knowledge, as well as their network of advocates, rather than conducting an analysis of individual AFH or programs. Nonetheless, they provide important recommendations for HUD oversight of AFFH, emphasizing the importance of more explicit guidance on what actions are sufficient to qualify as meaningful actions. None of these studies review AFFH programs with regards to meaningful actions.

An understudied aspect of the rollout of AFFH after 2015 is how well the relatively decentralized approach to problem definition and program development matches the need for action. As scholars more concretely identify local exclusionary land-use practices as core to persistent patterns of racial and socioeconomic segregation, as well as fair housing problems more broadly (Lens & Monkkonen, Citation2016; Rothwell, Citation2011; Trounstine, Citation2018, Citation2020), it becomes clear that fair housing law must prioritize change in racially concentrated areas of affluence (Goetz et al., Citation2019) and poverty. Thus, the procedural logic of AFFH implementation depends on a relatively benign local democracy that can recognize its own policies as problems, and take actions to change them (Goetz, Citation2021; Manville & Monkkonen, Citation2021). This merits further study, as a priori we do not expect exclusionary places to change voluntarily.

In their study, Steil and Kelly (Citation2019b) find that internal measures of racial segregation as well as the overall racial makeup of cities and their political ideology correlated with AFH goals. They draw from a wide selection of regions in the United States. Our focus on California means that the role of local politics is different and more constrained. In California, liberals are ambivalent about new housing development (Manville, Citation2021) and more liberal cities permit less new housing than less liberal ones (Kahn, Citation2011). We therefore select case studies based on variation in levels of racial segregation—rather than political ideology—and hypothesize that more racially segregated cities will react differently (less ambitiously) to the new AFFH requirement than less segregated places. Importantly, it is the more racially segregated places that need to take more aggressive actions to achieve regional fair housing goals.

California’s Housing Element Law and Planning Mandate System

For decades, California’s comprehensive plan mandate system has required local governments to update the housing element of their general plan (Baer, Citation1997, Citation2008). The system has multiple steps through which the state, in cooperation with regional councils of government, allocates housing growth targets to local governments. Local governments must periodically revise the housing element of their general plan for review and approval by HCD. The housing element has several components. It must not only demonstrate to the state that the jurisdiction has zoned capacity for new housing sufficient to meet its growth target, but also develop programs that remove constraints to housing development and, as of 2018, take meaningful actions on AFFH (for more, see Elmendorf et al., Citation2021).

After decades of implementation, this process has proved inadequate in supporting necessary housing production, with flaws at almost every step in the complex process (Dillon, Citation2017; Monkkonen et al., Citation2019; Zheng, Citation2021). Until recently, identifying concrete impacts of the housing element process was a challenge. Researchers therefore focused on whether California’s plan mandates increased housing production, not how this may have happened (Lewis, Citation2005; Ramsey-Musolf, Citation2017a). Lewis, for example, compared housing production in cities with compliant housing elements to those without and found that having a compliant housing element in 1994 (which many places did not) had no relationship to the number of permits issued in the subsequent six years.

Other scholars do connect California’s housing element process to improved housing outcomes. Ramsey-Musolf (Citation2016), for example, found that municipalities with compliant housing elements produced more low-income housing than those without. Yet places amenable to low-income housing production are presumably more likely to comply with state housing law, and the study uses an admittedly non-causal approach. Palm and Niemeier (Citation2017) find that after the San Francisco Bay Area’s Council of Governments improved their regional fair-share housing allocation system in 1999 by giving higher targets to places with more job accessibility, housing production shifted to municipalities that received higher targets. However, as they write, the results “could also be the result of other factors between the two data points, including changing economic conditions, a shift in the interests of affordable housing developers, and greater local political support for affordable housing” (Palm & Niemeier, Citation2017, p. 385).

The important deficiency in the existing literature is that the mechanisms through which these plans may lead to a difference in outcomes are unclear. Recently, however, research has begun to focus on these mechanisms, specifically whether planned sites for new housing have been built out. Prior to 2021, housing elements did not actually lead to rezoning; they simply identified parcels with existing potential for housing (Monkkonen & Friedman, Citation2019; Monkkonen et al., Citation2023a). The role of sites in housing development is presumably a key mechanism of the plan’s impact. Kapur et al. (Citation2021) assessed housing development activity on parcels designated as apt for low-income housing development by jurisdictions in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2014. They found that developers built housing on only 10 percent of these sites during the subsequent eight years, while during the same period, 70 percent of housing development occurred on sites not listed in a housing element. This research shows the importance of assessing concrete changes spurred by housing elements themselves, rather than just associations between cities with compliant or “better” planning documents.

Incorporating AFFH into California Housing Element Law

California’s adoption of AFFH creates the potential for substantial influence on local government action, perhaps more than the HUD rule, because it is built into the existing planning mandate system. California’s 539 jurisdictions are required to update their housing plans at least once every eight years (California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), Citation2023), in contrast with a more limited scope for HUD grantees. For example, from October 2016 to January 2018 HUD reviewed only 49 AFH (Steil et al., Citation2021). Moreover, unlike federal AFH, which are automatically approved after 60 days if HUD does not comment on them,Footnote3 California housing elements must be approved by HCD. If they are not deemed compliant, local governments face consequences.Footnote4

State law required California’s local governments to have their most recent Housing Element update certified by HCD by October 2021, but AFFH and other new requirements led to substantial delays in cities and counties obtaining state approval (Monkkonen et al., Citation2023a). Indeed, no plans were deemed compliant by the October deadline, and one year later roughly half of the plans were still out of compliance. Among other problems with housing elements, every initial determination letter from HCD cited incomplete AFFH sections as a reason for not approving the plan.

In addition, California’s Government Code section 8899.50 now requires “meaningful actions” that go beyond combating discrimination to “overcome patterns of segregation and foster inclusive communities.” The guidelines issued by HCD in 2021 require local governments to set goals and policies to meet this meaningful action requirement. They state that these actions must have “the intention to have a significant impact, well beyond a continuation of past actions, and to provide direction and guidance for meaningful action” (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 52). They define meaningful actions as “Significant actions that are designed and can be reasonably expected to achieve a material positive change that affirmatively furthers fair housing by, for example, increasing fair housing choice or decreasing disparities in access to opportunity” (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 66).

We cannot, however, easily discern how meaningful an action must be to qualify as sufficient by reading these guidelines. The guidelines do offer concrete instructions in two places. The first is the checklist of questions used by housing element reviewers. The checklist again asks whether housing elements identify metrics, milestones, and timelines for each action. This is necessary but insufficient information to determine whether a program is meaningful.

The second is a list of nearly 50 example programs (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 72), in four categories.Footnote5 The example programs themselves illustrate the challenge of assessing whether a program represents a meaningful action. Some programs, like “Increase the visibility of the jurisdiction’s small business assistance programs” or “Extend search times for particular groups with housing choice vouchers,” may advance AFFH goals, but not as much as others, like “Increase number of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) allowed per site” or “Preserve Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing or mobile home parks.”

The goal of California’s housing element—meeting housing needs and accommodating growth—overlaps with the first goal of AFFH. Almost all housing element programs could be coded as “reducing disparities in housing need.” For this reason, we focus exclusively on the programs cities identify as AFFH actions to understand how they react to this mandate. We also base our understanding of goals for local action on these guidelines, that cities should create land-use rules that will allow for integrated and balanced neighborhoods, direct investment such that all neighborhoods have similar levels of public infrastructure and services, and actively facilitate low-income housing development in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

Program Evaluation in Plan Quality Research

Program impact evaluation has a large and robust literature and set of evidence-based methods; however, unlike plan quality research, it relies on ex post measurement of outcomes (Guyadeen & Seasons, Citation2018). In spite of this limitation, planning scholars recognize the importance of some measurement of potential plan impact, and there is a renewed effort to evaluate plan quality (Baer, Citation1997; Lyles & Stevens, Citation2014; Seasons, Citation2003). Debate continues over how to measure several aspects of plans, such as a comprehensive measure of their quality (Norton, Citation2008).

The plan quality literature uses measures in seven domains to evaluate plans—goals, fact base, policies, participation, inter-organizational coordination, implementation, and monitoring (Berke et al., Citation2012; Stevens et al., Citation2014). Researchers assign quantitative measures to score each domain of a plan, but these measures do not attempt to evaluate a plan’s actions with respect to achieving a larger goal. For the first three domains, they list possible goals, policies, or fact bases, and then count how many the plan includes. For example, of all the goals, fact bases, and policies a city could take to mitigate coastal harms, how many are included in the plan? Using this approach to evaluate AFFH programs would entail enumerating the set of possible programs that a city might undertake and then quantifying how many a city includes. This approach would be less effective in assessing the potential impact of fair housing programs because cities are instructed to create programs tailored to their circumstances, not undertake all possible actions.

One study of plan quality focuses on California’s housing elements (Ramsey-Musolf, Citation2017b) and emphasizes the importance of connecting plan quality research to outcomes. In his comprehensive review of plan quality research connected to housing plan mandates, Ramsey-Musolf also alludes to the importance of mechanisms of change in the plan, noting that the plan itself is not an intervention.

Similar to Steil and Kelly (Citation2019b), we focus on the measurement of the domain of implementation rather than overall plan quality, recording whether each policy listed in a plan is new, has measurable objectives, and has a timeline—similar to plan quality studies, e.g., Berke and Godschalk (Citation2009). Although existing research deems these sufficient to determine quality in this area of a plan, we consider that they are inadequate to assess potential impact. This scholarship does not consider whether policies, if realized, will lead to meaningful progress toward plan goals. Therefore, notwithstanding the fact that real-world program outcomes can only be determined after the passage of time, we consider that evaluations should attempt to assess the impact of a plan’s proposed actions using and improving upon existing best practices (Berke, Citation1996).

Data and Sampling Approach

Our primary source of data is the AFFH section of housing element updates from eight case study municipalities, supplemented with secondary data from the census. We analyze three components of the AFFH section: the analysis of issues, the programs (which we also compare to their previous housing element programs), and the location of the parcels they selected as potential sites for new housing. We sought case studies that varied by their level of racial segregation, given the origins of AFFH and its focus on creating integrated and balanced neighborhoods. This allows us to examine the proposition that more segregated cities react less ambitiously to the fair housing requirement, and the fact that more segregated cities will need to take more aggressive action.

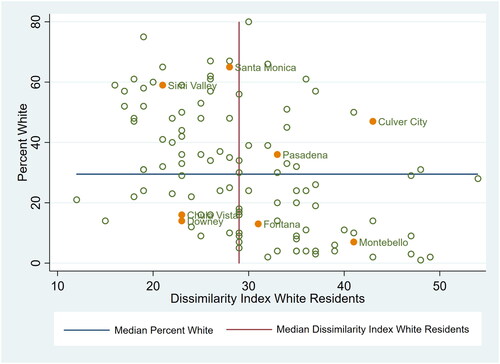

Given that exclusion occurs at multiple geographic scales, we first measured within-city and within-region racial segregationFootnote6 for the municipalities in Southern California with populations between 40,000 and 500,000 (to minimize the role of city sizeFootnote7). We then chose two cities from each of four groups: high internal segregation and high regional segregation, high internal segregation and low regional segregation, low internal segregation and low regional segregation, and low internal segregation and low regional segregation. shows these measures, the four groups, and the eight cities we selected as cases.

Figure 1. Regional and internal segregation by race for cities in Southern California with between 40,000 and 500,000 residents.

Source: US Census Bureau (Citation2022).

We selected the two cities in each group to vary on one measure of how difficult it will be for them to update their housing element. We measure this difficulty using a ratio between the number of housing units the city has to accommodate in their 2021 Housing Element and the number of housing units for which they stated they have capacity in their 2014 Housing Element. The higher this ratio, the more rezoning a city will likely need to undertake to meet its statutory obligations. For example, Santa Monica and Simi Valley both reported to HCD a capacity of roughly 3,500 units in 2014, but Santa Monica was assigned a target three times larger than Simi Valley in 2021—8,873 units compared to 2,786—a target that was much higher than its stated capacity for development in 2014.

In , we present the descriptive characteristics of these eight municipalities. In terms of internal and regional segregation by race, Pasadena and Culver City are high–high, Montebello and Fontana are high–low, Santa Monica and Simi Valley are low–high, and Downey and Chula Vista are low–low.

Table 1. Selected characteristics of eight case study municipalities and southern California median.

These eight municipalities places vary in their relative affluence, housing tenure, location within the region, local politics, and change in housing growth targets. For example, median incomes range from $67,000 in Montebello to $105,000 in Culver City, and share of homeowners ranges from 29 percent in Santa Monica to 71 percent in Simi Valley. The political attitudes and the reputation of their governments also differ substantially. Simi Valley, for example, is notorious for its conservative attitudes, especially around policing and race (North, Citation2020), whereas Santa Monica’s reputation for progressive voters suggests it is more likely to embrace an AFFH mandate than most cities (Clavel, Citation2011). Online Appendix A Table A1 reports additional data on these municipalities, such as existing Low-Income Housing Tax Credit units in the case study cities and recent permitting activity.

For context on the housing element process, we report some basic data for these eight municipalities in , including the consultant (if one was used), the date HCD approved their housing element, the number of drafts submitted to HCD, and the length of the final housing element and its appendix. Consultants play an important role in housing element development (Ramsey-Musolf, Citation2017b), but even cities that hire the same consultant create very different plans. The shortest housing elements (those of Montebello and Simi Valley) are about 140 pages, whereas the longest (Santa Monica) is over 1,500. We consider that to some extent, length reflects greater effort on the part of the city, at least to obtain approval from the state.

Table 2. Summary of housing element characteristics for case study cities.

Methods

We analyze the three main components of California’s AFFH requirement—the analysis of fair housing issues, the programs established as meaningful actions to address fair housing issues, and the jurisdiction’s plan for siting new housing. This section describes our methods, including our approach to exploring the proposition that more segregated cities followed the AFFH mandate in a different way than less segregated cities.

Method 1: Evaluating the Analysis of Fair Housing Issues

State law requires local governments to undertake a comprehensive assessment of fair housing issues to guide their meaningful actions. HCD requests that these assessments focus on six primary areas: outreach and enforcement capacity for fair housing laws; integration/segregation of people with protected characteristics and lower incomes; racially and ethnically concentrated areas of poverty (and affluence); disparities in access to opportunity; disproportionate housing needs; and the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) sites inventory (HCD, Citation2021a, pp. 28–45). Like HUD, HCD provides detailed instructions for fair housing analysis and instructs local governments to use state-provided data, local knowledge, and community input for their assessments.

Evaluating the completeness and quality of a jurisdiction’s analysis of fair housing conditions and challenges is important because the analysis should, at least conceptually, drive AFFH programs. We expect that jurisdictions with more complete AFFH analysis sections will also have more specific and meaningful actions. To assess the quality of analysis, we created a standardized rubric (Online Appendix B) to score six questions, the descriptions of low-income neighborhoods, overall clarity, assessment of constraints to new housing, details of “other relevant factors” discussions, quality of discussions of affordable housing in high-income neighborhoods, and the evaluation of sites for new low-income housing.

Two reviewers read and coded the analysis sections separately using previously defined criteria and following standard practice (Stevens et al., Citation2014). We score the first five questions on a scale from one to three, with one indicating that the city did not address the requirement, two that the city partially or minimally addressed the question, and three showing that the city completely or comprehensively answered the question. We score the sixth question on a scale of one to four. A score of one indicates that the city mapped the sites relative to opportunity indicators, but did not provide statistics. A score of two means that the city provided tables or calculations relating sites to one or more opportunity indicators, like household incomes, but did not provide information on this indicator across neighborhoods in the city.Footnote8 A score of three represents an attempt to normalize the tables using data from the city, but in an ineffective manner. A score of four means the analysis assesses sites by neighborhood with a denominator like the neighborhood’s area compared to that of the city.

We then reconciled differences in our evaluation with a third reviewer by refining our established criteria and reviewing previous scores using the updated criteria. We created a final score for each municipality by summing the scores for these six questions, electing not to use weights for any of these questions due to their equal relative importance.

Method 2: Describing AFFH Programs

We describe AFFH programs in the housing element by building on the plan evaluation literature and recent work by Steil and Kelly (Citation2019b). We start by determining which AFFH goal the program is working toward and then assess the type of action. Cities often group their programs in different and more specific ways than the four AFFH goals; thus, we also categorize actions by sectors of activity, such as education or housing production. We create nine sectors with 42 sub-sectors of action, which we present in detail in Online Appendix A Table A2. reports these categories, which range from education and outreach to assistance to lower-income households.

Table 3. Nine sectors of Affimatively Furthering Fair Housing programs.

Our sectoral classification is mutually exclusive, even though programs span more than one sector. For example, an informational campaign about new streamlining programs for affordable developers can be categorized as “information” or “housing production.” In these cases, we identify the program’s action, rather than its aspiration. We classified the example of an informational campaign for developers as “information,” not “housing production,” because its action is informative.

Finally, we review AFFH programs to determine whether they are new, have timelines, and report quantified objectives. In their 2021 housing element updates, cities are expected to indicate whether programs are new, but they do not always do this. Therefore, we compare 2021 AFFH programs to those in the previous housing element (from 2014) and classify programs as (1) completely new, (2) based on an old program with significant differences, (3) similar to a previous program with no significant changes, (4) identical to a 2014 program. For a summary, see Online Appendix A Table A3.

Method 3: Evaluating Meaningful Action

In order to assess whether AFFH programs represent meaningful action, we use a multi-step coding process. Prior to coding, we established definitions of meaningful, somewhat meaningful, and not meaningful action based on HCD guidance. This guidance emphasizes the need for timelines, concrete actions, milestones, metrics, and AFFH goals, on the one hand, and provides examples on the other, such as a program that “explores feasibility on an ongoing basis” compared to a commitment to “rezone 50 acres to the high density district by October 2021” (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 55).

Meaningful actions are programs that make substantial changes to current regulations or processes, commit substantial resources, assist a large number of individuals, have significant potential to spur substantial action by the private or nonprofit sector, or are related directly to reversing the legacy of racial segregation. Somewhat meaningful programs are those with concrete actions, that will help a moderate number of individuals, represent resource expenditures by the city, and/or have the possibility to induce some action by the private or nonprofit sector. Not meaningful programs are those that have few or no concrete actions, assist a small number of people, and/or represent limited resources (staff time or money) by the city. The definition of substantial, in terms of regulatory reform, resource commitment, or households assisted, is to some extent conditional on the size of the city.

We also consider the inclusion of measurable objectives and timelines, as well as progress toward goals if implemented successfully. For each program, we consider the degree to which, if completed, it would achieve “a material positive change” (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 66) to advance one or more of the four AFFH goals. Examples of programs in the results section will illustrate our definition of material positive change.

We revised these criteria twice, first after a round of coding and reconciliation of inconsistencies between coders and then after creating sectoral categories to ensure consistency across sectors. After two coders classified each AFFH program, a third coder reviewed and compared individual evaluations. In the first round, about one quarter of programs had discrepancies between coders. We reconciled these through a review of program objectives and refining of criteria, and then coders went through the programs a second time with the updated criteria.

We coded programs by sector of actions () in part to improve consistency in the coding of meaningful action. We compare programs in the same sector in different cities to ensure we coded similar programs from different cities consistently. As an indicator of this step’s importance, we changed roughly 15 percent of the original scores to be consistent within sectors. This iterative review and coding process standardizes the classification, reduces coder bias, and, importantly, creates explicit criteria to determine whether a program is meaningful, criteria that can be used by other researchers or agencies like HCD and HUD.

After evaluating the meaningful action of individual programs, we calculate a summary score for each city’s programs. We assign meaningful programs a six, somewhat meaningful programs a three, and not meaningful programs a one. These weights reflect the substantial difference in the potential impact of programs in making progress toward AFFH goals. Given that this summary score will reflect how many programs a city has, to some extent, we also report and assess the average program score for each city.

Method 4: Evaluating Land-Use Plans for New Low-Income Housing

Local governments in California must submit to the state lists of parcels where a target number of new housing units can be built. To satisfy the requirements for new low-income housing, jurisdictions must identify sites between 0.5 and 10 acres that are zoned at a “default” residential density, typically at or greater than 30 units per acre.Footnote9

In the AFFH guidelines, HCD instructs jurisdictions to show that their inventory of sites for new housing decreases segregation for protected classes and by income within the jurisdiction (HCD, Citation2021a, p. 46). They suggest a method local governments can use to assess what share of sites for low-income housing are located in the lower-income neighborhoods of the city. None of the jurisdictions we studied used this analytical approach successfully, although some attempted to present a breakdown of the incomes of neighborhoods with large shares of sites.

We use the Fair Housing Land Use Score (FHLUS) to quantify the distribution of multi-family zoning and sites for new housing across neighborhoods, ranked by household incomeFootnote10 (Monkkonen et al., Citation2023b). The score ranges from −1 to 1: a higher score indicates that more sites for new housing are located in higher-income neighborhoods. Cities with all of their housing element units located in the lowest-income census tract would get a score of −1, while those with all units in the highest-income tract would have a score of 1 (Online Appendix C describes the calculation of the FHLUS in greater detail).

We generate the FHLUS for the distribution of lower-income sites, all sites, and, finally, rezoned sites for each city. The distribution of rezoned parcels is especially important because rezoning is the most significant change a city can make to its land-use plan. Many cities rezoned substantially, for example Culver City and Santa Monica rezoned for at least as many units as their housing targets, and Downey, Fontana, Montebello, and Simi Valley rezoned from 40 to 80 percent of their target. Pasadena and Chula Vista did not rezone at all, meaning they were able to meet their growth target without substantial changes to land-use patterns (for more on rezonings in 2021, see Monkkonen et al., Citation2023a).

In addition to the FHLUS, we calculate a dissimilarity index for each city to measure the evenness/concentration of sites across neighborhoods. We calculate this index using the standard formula for the dissimilarity index, but instead of two percentages of population groups in the city, we use the share of units in each tract and the share of the city’s non-open space area in each tract.

Method 5: Examining the Proposition That AFFH Analysis and Action Relate to Segregation Levels

In order to explore the hypothesis that more segregated cities reacted differently to the new AFFH mandate, we examine the difference between cities’ scores based on the coding of their analysis and programs and the FHLUS in relation to the two measures of racial segregation. We observe the correlation coefficients, with the obvious limitation that the sample size will not produce statistically meaningful results.

Limitations

The current paper is limited in part by the relatively small number of cases and because it is the first attempt to assess the how meaningful AFFH programs are. As mentioned, determining whether programs are meaningful is challenging ex ante, as outcomes are not yet observed. In addition, we do not attempt to measure the cohesiveness of AFFH programs together, as plan quality scholarship might, as it would introduce more subjectivity into the process. Moreover, cohesiveness is less important here, given that AFFH goals are predetermined by law and not created within a plan.

We hope that further research builds additional ways to concretely define criteria for goals in a simplified and replicable manner. Additionally, future research could assess whether local AFFH analysis identifies problems that external sources, including advocates or scholars, have documented, and evaluate the connection between problems identified in the analysis section and the focus of AFFH programs.

Results

In this section we first present the results of our assessment of cities’ AFH, a description of the AFFH programs, and our evaluation of how meaningful they are, with some examples. We then discuss the analysis of sites’ inventories and our measures of whether they fulfill the expectation of AFFH. Finally, we compare municipal scores from the different areas of assessment.

We note that housing elements in 2021 were different from previous housing elements in many ways, not only in terms of the new AFFH requirement. New reporting requirements, laws mandating new sites’ analyses, larger housing growth targets, and closer scrutiny by HCD combine to explain the increase in the number of programs by 85 percent on average in the eight cities we analyzed (see Online Appendix A Table A4 for the total number of housing element programs by city).

Table 4. Evaluation of fair housing analysis.

Results 1: Evaluating the Analysis of Fair Housing Issues

Prescriptive state guidelines for the analysis section mean that most are similar in structure and content, though some are included as an Online Appendix and others as a chapter in the housing element. The AFFH sections analyze the city’s current housing conditions, then discuss the spatial distribution of various social and housing indicators, and finally describe programs and actions. Their length varies substantially from 34 pages (Downey) to more than 90 pages (Pasadena, Fontana, Culver City, and Simi Valley). Although maps and tables take up many of these pages, we again consider length to reflect effort to some extent.

Some AFFH sections enter into greater detail than others, and focus on different issues. For example, Santa Monica emphasizes historical redlining patterns and disparities between neighborhoods, but most other cities do not cover this history. Chula Vista identifies a racially/ethnically concentrated area of poverty (R/ECAP), substandard housing conditions, and displacement risks on the city’s west side. Downey focuses on its industrial history.

We report a summary of our evaluation of the eight cities’ AFH in . Montebello and Santa Monica scored the highest (16 and 17 out of 19 possible points, respectively) and Chula Vista the lowest (12 points).Footnote11 The next lowest scoring cities, Downey, Pasadena, and Simi Valley, all scored 14.

Nearly all cities included maps showing the spatial distribution of indicators like poverty and non-white neighborhoods, but only some cities included explanations of conditions in low-income neighborhoods. Only Chula Vista and Fontana have a R/ECAP as designated by HUD, and as such, they provided the most detailed analysis of the conditions and land-uses in that census tract. Fontana explains conditions, history, land uses, and proximity to sources of pollution in its R/ECAP, and compares it to its high-resource areas to highlight disparities. Most cities did not describe the conditions in their lower-income neighborhoods in detail. One exception is Culver City, which incorporates ample demographic and land-use information to evaluate whether any neighborhoods could be considered R/ECAPs.

Fontana, Downey, and Simi Valley discuss zoning-related constraints in their AFFH section. Santa Monica and Pasadena have a less thorough analysis. Chula Vista and Culver City have no formal discussion of governmental constraints in their AFFH sections, though Culver City does identify “land use and zoning laws” as a contributing factor to displacement risk.

The required AFFH analysis of “Other Relevant Factors” is the most open-ended section; thus, the information a city includes (or excludes) can be revealing. Some cities acknowledge historical discriminatory practices. For example, Culver City discussed its founding as a “sundown town,” and Downey mentioned its history of redlining and racially restrictive deed covenants. We also notice some absences in this section. For example, Simi Valley does not mention its “Managed Growth Plan,” which capped residential growth at 292 units per year. This statute is currently superseded by state law, yet its role in limiting housing growth is an obvious fair housing issue.

Several AFFH analyses discussed the importance of housing opportunities in neighborhoods with resources and access to public services, but none presented a sites analysis in the manner HCD requested. For example, Fontana set its objective to “increas[e] housing opportunities in areas with the most resources” (City of Fontana, Citation2021, pp. 3–123) but did not use available data to ascertain whether its plan will accomplish this goal. Almost all cities used both maps of sites and tables of the share of units in neighborhoods of different income levels. However, only Santa Monica attempted to normalize the site or unit distribution by a common denominator (e.g., city area, total housing units). This is important to show the balance of sites compared to citywide resources, and without a denominator the analysis is not informative. State reviewers cannot judge a plan’s effect using the proportion of units in neighborhoods with different poverty rates, without knowing how many of the city’s neighborhoods have these poverty rates (for more, see Monkkonen et al., Citation2023b).

Santa Monica illustrates an attempt to normalize by a citywide denominator. They report the share of units relative to the share of citywide households at different income levels. That is, the city reports the share of low, moderate, and above-moderate site units in tracts divided by five income categories, along with the citywide share of households that fall into these income categories. Yet this fails to accurately present the relative distribution of sites across neighborhoods because it mixes the units of analysis, and does not report the share of the city that corresponds to the incomes of the tracts in which units are located. To illustrate the problem, consider that only one tract appears in the highest reported income category (>$136,500). The citywide denominator shows that 3 percent of the city’s households have incomes in this category, yet the single tract accounts for 11 percent of the city’s area. Moreover, given the correlation between income and density, normalizing neighborhoods by their population when analyzing sites’ distribution biases the outcome to seem more pro-opportunity than it actually is.

Results 2: Describing AFFH Programs

Our sample of cities have between 23 and 45 AFFH programs, which represent between about a third and over three quarters of their housing element programs. Slightly more than half of these programs focused on the most general of the AFFH goals, reducing disparities in housing needs and access to opportunity. The smallest portion of programs address the goal of replacing segregated living patterns, possibly because this is the most politically challenging. reports the share of programs by AFFH goal.

Table 5. Summary of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing program characteristics by municipality.

In terms of sector, over a quarter of all AFFH programs focus on education and outreach. These programs mainly involve advertising and dissemination of material as well as holding workshops and housing fairs. One fifth of AFFH programs focus on bringing assistance to lower-income households through actions such as direct assistance to tenants for code violations or providing maintenance and repair support. Another fifth of programs address housing production, primarily through specific changes to zoning codes.

The vast majority of programs (over 85 percent) have clear timelines, and roughly 80 percent have measurable objectives. Montebello and Chula Vista do not include clear timelines for a substantial share of program actions, and Fontana and Montebello fail to define measurable objectives for many of the actions they propose. summarizes additional important dimensions of these programs—how many each city has, what share have concrete timelines and measurable objectives, and AFFH goal they address.

Table 6. Share of programs by Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing goal.

This summary shows that the AFFH requirement led to the creation of new programs, as the majority (56 percent) did not have a precursor in a 2014 program. The share of new programs varies widely across cities, however. In Downey, for example, the majority of 2021 AFFH programs (74 percent) are new, whereas in Pasadena only one third are.

The share of new programs varies by sector. For example, all or nearly all of the programs in the sectors of economic development (100 percent) and information strategy (75 percent) are completely new. Some cities, like Simi Valley, already held workshops and fairs on fair housing and did not make any substantial changes to these programs, but proposed to increase outreach through social media accounts.

Nearly two thirds of the “housing production” programs are new. Culver City, for example, created a program to facilitate hotel/motel conversion and evaluate city-owned sites for potential affordable housing projects focused on special needs populations. Santa Monica had a program to spur affordable housing development previously, but in 2021, the city introduced more substantial reforms, such as removing density caps and incentivizing housing production on parking lots. Additionally, many new programs emphasized reducing housing discrimination.

In contrast, less than half of programs focused on “assistance to low income households” are new. Many simply expanded upon or scaled up pre-existing programs. For example, Montebello broadened an existing program offering home improvement grants to senior homeowners to include all low-income households and increased the size of grants from $10,000 to $50,000.

Results 3: Evaluating Meaningful Action

Our evaluation finds that 17 percent of programs are meaningful, whereas 36 percent are somewhat meaningful and 47 percent are not meaningful. We present a summary by city—the total number of programs, the number that are meaningful, a summary “meaningfulness” score, and an average “meaningfulness” score—in .

Table 7. Meaningful impact of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing programs by municipality.

The cities with the highest share of meaningful actions (Downey, Pasadena, and Santa Monica) have between seven and eight each. Pasadena stands out as the municipality with the highest summary score. Downey and Santa Monica have relatively few programs (25 and 23) but many are meaningful, leading to a high average program score. Half of the sample (Chula Vista, Culver City, Fontana, and Montebello) only have a few meaningful programs, between two and four. With the exception of Culver City, these cities have fewer overall programs and the lowest summary scores.

Santa Monica’s meaningful programs mainly focused on increasing housing production through zoning changes in non-residential areas and surface parking lots. Their pilot Right of Return program, although a pilot, is meaningful because of its direct approach, through reparations, to reversing the legacy of racial segregation. The program gives former Santa Monica residents displaced by past urban renewal policies priority in the city’s affordable housing waitlist.

Downey’s meaningful programs also focused on housing production and zoning changes, including substantial increases in allowed density, and the use of city-owned land for the development of affordable housing. They also have one of the less common place-based investment programs, which targets improvements in parks and transit in lower-resourced parts of the city.

Pasadena’s meaningful programs, on the other hand, mostly focus on providing assistance to lower-income households. For example, the city proposes to enter a public benefit agreement with the California Statewide Communities Development Authorities to acquire existing apartment buildings for lower-income households. Like Santa Monica, Pasadena proposes a zoning ordinance to allow affordable housing development on the premises of religious institutions.

The share of meaningful programs varies widely by sector, as reported in Online Appendix A Table A5. Meaningful programs fell into four categories: first, location-specific programs that make substantial commitments to zoning reforms or code changes; second, programs that preserve a large number (over 700) of deed-restricted units and/or rehabilitate low-income multi-family housing; third, programs requiring substantial financial commitment from cities for housing assistance; and, finally, programs that are directly related to the more challenging AFFH objectives—for example, reparations for specific discriminatory actions by local governments.

The majority of programs geared toward providing assistance to low-income households fell into the somewhat meaningful category, as did nearly half of programs on housing production. While many of these programs had measurable goals and objectives and promised to improve housing conditions, they will not substantially improve housing conditions or production. An example is Simi Valley’s program to build 200 affordable units by 2029. Even though this is an important action to address housing disparities, it was not commensurate with the state-identified housing need for low-income housing in the city (over 1,200 units) and much less aggressive than other cities’ proposals (e.g., Fontana’s program to build 2,950 low-income units).

The education and outreach category had the highest share of not meaningful programs (40 percent). These programs include actions such as disseminating informational materials or updating websites and social media profiles with additional information. Other not meaningful programs were infrastructure and maintenance programs, such as graffiti removal (Culver City).

Results 4: Evaluating Land-Use Plans for New Low-Income Housing

We present summaries of measures of the distribution of sites for new housing in , including the FHLUS for all new housing development, new low-income housing, and existing multi-family zoning. We also calculate and report how much of the city’s state-assigned housing target was met through rezonings and the dissimilarity index for units in housing element sites.

Table 8. Distribution of sites for new housing and existing zoning.

Our results show that every city except Fontana and Montebello is planning for more new housing development—and new low-income housing development—in their comparatively lower-income neighborhoods. Chula Vista and Culver City have negative scores, but they are close to zero, indicating a rough balance in unit distribution between higher- and lower-income neighborhoods. On the other hand, Santa Monica and Simi Valley have extremely low negative scores, illustrating that nearly all of their RHNA sites are located in their lower-income census tracts.

By comparing a city’s scores in we reveal the role of inertia in new plans for housing development. For example, comparing the FHLUS for housing element sites to the FHLUS for existing zoning indicates whether the city’s plan changes the status quo by siting new multi-family housing in neighborhoods that are more affluent than existing multi-family areas. All but two cities, Santa Monica and Simi Valley, do this. They stand out because their housing element sites score so poorly on the FHLUS, even worse than their existing multi-family zoning.

The dissimilarity index indicates the share of units that would have to move for them to be evenly distributed across a city’s census tracts. Simi Valley has the highest dissimilarity index (0.78), meaning it would have to reallocate almost 80 percent of its units to achieve an even distribution. Culver City has the most even distribution of sites (a dissimilarity index of 0.17). An even distribution does not mean sites are located in more affluent neighborhoods, but it makes it more likely. Fontana and Montebello, for example, have lower dissimilarity index values (around 0.45) and positive FHLUS.

presents maps of housing element sites for each city. Online Appendix D describes the distribution of housing sites in each city’s inventory in greater detail, including graphs of the FHLUS for different samples of sites.

Figure 2. Maps of housing element sites and tract median household income.

Source: Authors with US Census Bureau (Citation2022), California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Citation2023), City of Chula Vista (Citation2022, Citation2023), City of Culver City (Citation2021), City of Downey (Citation2021), City of Fontana (Citation2021), City of Montebello (Citation2021), City of Pasadena (Citation2022), City of Santa Monica (Citation2021), City of Simi Valley (Citation2022), GreenInfo Network (Citation2022), San Diego County Assessor (Citation2023), and Southern California Association of Governments (Citation2022).

Results 5: Examining the Proposition That AFFH Analysis and Action Relates to Segregation Levels

We observe some correlations between the components of the AFFH section. Cities with better analysis scores have more programs with timelines and measurable objectives (a correlation of 0.6) and higher average program scores (a correlation of 0.5). That is to say, housing elements that meet HCD guidelines more closely performed better in our qualitative evaluation of programs.

However, cities with higher program scores were more likely to concentrate their sites for new housing and low-income housing in their less affluent neighborhoods. Santa Monica and Pasadena, for example, had the second and third worst FHLUS for all sites and lower-income sites, and high program scores. On the other hand, Fontana and Montebello, which had the lowest and third lowest program scores, had the two highest FHLUS. These two cities’ FHLUS was especially high for their rezoned sites, meaning their housing element is changing land use in a substantial way that advances fair housing goals. (The correlation between the low-income FHLUS and overall program score is −0.5).

The fact that cities with more meaningful programs are at the same time failing to amend their land-use plan’s segregated status quo, and vice versa, is striking—it is the cities with more white residents and higher incomes that are not working to reverse the legacy of racial segregation in their land-use plans. The correlation between the share of white residents and meaningful programs is 0.5, but with the FHLUS it is −0.8. Cities that are more segregated internally are also less likely to change the land-use status quo. The measure of internal dissimilarity is positively correlated with FHLUS (0.6). On the other hand, it has a near-zero correlation with the programs’ scores.

Montebello and Pasadena offer an instructive contrast. Pasadena has a number of meaningful programs, but its housing element proposes no rezoning to meet its RHNA obligation (although it is rezoning land for housing outside of the housing element), or meaningful changes to the housing segregation in its land-use rules. On the other hand, Montebello is planning for low-income housing development in its more affluent neighborhoods even though it does not propose many meaningful AFFH programs.

These correlations should be taken as exploratory, given the small sample size, but they raise important issues for further research. The negative correlation between program quality and site distribution also raises questions for state regulators. Should they consider AFFH programs separately from a city’s plan for new housing development? How should they balance these two important components of a local fair housing strategy? If nothing else, the negative FHLUS for most municipalities indicate a crucial missing component to fair housing oversight and AFFH implementation.

We conclude with an observation on whether the analysis of the distribution of housing element sites across neighborhoods matters. Apparently it does not. Santa Monica came the closest to following HCD guidelines in evaluating where they were planning for new housing development (as reported in ), yet the quality of analysis did not correlate with performance—they had the second worst FHLUS in our sample.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Our analysis of the AFFH components of eight municipal housing plans shows that many new fair housing programs can be attributed to a new state mandate even if many of the planned actions do not lead to meaningful progress in achieving the law’s goals. Unfortunately, few of the AFFH programs we reviewed make substantial changes to the municipal government’s major levers of action on racial (or socioeconomic) segregation—land-use policy and infrastructure investment. Instead, many focus on increasing outreach and education about fair housing laws and existing city services. These goals are well-intentioned and will likely help some people, but hosting workshops and increasing advertising budgets are not likely to produce meaningful progress toward the goals of AFFH. Because most cities fail to use their land-use powers to create integrated neighborhoods, their plans perpetuate housing segregation by identifying potential sites for low-income housing in cities’ lower-income neighborhoods.

Limited progress on land-use reform likely arises for several reasons. To change the status quo is politically controversial, expensive, technically challenging, and may work against real or perceived fiscal incentives (Freemark et al., Citation2020). City staff and consultants may be hesitant to include substantial commitments to politically controversial programs in order to to expedite the approval of the housing element and minimize future work on implementation (Basolo, Citation1999). The housing element is not directly a budgetary document, and its programs are competing with other, possibly more popular, city priorities for funding and staff time.

Given that cities may focus on meeting the minimum housing element commitments necessary for HCD approval rather than setting out a plan for transformative change, we recommend that the state revise the checklist it uses to assess compliance with the law. HCD should create the expectation that cities must take meaningful action rather than simply do something. Standardizing reporting requirements for housing element programs, as HCD recently did for the sites’ inventories in 2021, may seem like a small change, yet it could make AFFH programs meaningful by improving state review. Without complete, specific, and consistent information, reviewers cannot effectively evaluate program impact across cities.

We recommend that HCD require a Microsoft Excel form with required fields for program timeline, measurable objectives, responsible parties, resource commitment, connection to existing programs, AFFH goal, program area,Footnote12 and sector. HCD should expand on its list of example programs (HCD, Citation2021a, pp. 72–74), provide clear examples of the level of detail and commitment it expects, and clarify what constitutes a meaningful set of programs. Jurisdictions need clarity as to the types of programs that will be accepted as meeting the statute’s meaningful action threshold.Footnote13

The lessons and recommendations from this study are relevant outside of California, both for federal review of AFH and for other state governments considering the adoption of an AFFH law. State governments have greater authority over local land-use planning than the federal government; thus, state AFFH mandates have greater potential for inducing local reforms. However, state governments considering similar laws should recognize that California’s mandate is built into the state’s periodic planning process for housing growth. Without an existing process, it will necessarily be a larger undertaking and less likely to be effective.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.6 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for supporting this research. We also thank Michael Lens, Moira O'Neill, George Galster, participants in seminars at UCLA's Department of Urban Planning and Sciences Po Paris, and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paavo Monkkonen

Paavo Monkkonen is Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Aaron Barrall

Aurora Echavarria is a PhD candidate in Urban Planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Aurora Echavarria

Aaron Barrall is a housing data analyst at the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

Notes

1 This first finding echoes the results of Steil and Kelly’s (Citation2019a) studies on federal AFH.

2 As Owens (Citation2019) demonstrates, housing segregation is a driver of socioeconomic segregation, which in turn contributes to racial segregation.

3 HUD did reject roughly one third of AFH in this period (Steil & Kelly, Citation2019a).

4 For example, cities that miss their deadlines for HCD approval lose the ability to deny housing projects that set aside a substantial share (20 percent) of units for low-income households (known as the “Builder’s Remedy”) and are ineligible for certain state grants (Dillon, Citation2022).

5 The four categories are Housing Mobility Strategies, New Housing Choices and Affordability in Areas of Opportunity, Place-based Strategies to Encourage Community Conservation and Revitalization, and Protecting Existing Residents from Displacement.

6 We measure within-region racial segregation by using the share of non-Hispanic White residents of a city, and within-city racial segregation using the dissimilarity index of non-Hispanic White individuals.

7 There are 209 municipalities in the seven counties of Southern California (Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, and Ventura), two of which have more than 500,000 residents while 87 have fewer than 40,000, leaving us with a sampling frame of 120 cities.

8 Most cities report the share of units by neighborhood poverty rate or income level, for example. However, they do not report how many neighborhoods in the city fit these categories. So it may seem like a low share of units are in high-poverty neighborhoods, for example, but actually the units are relatively concentrated because the city itself only has one high-poverty neighborhood, and a large share of units are not in high-poverty neighborhoods yet still in the city’s lowest income bracket. For more on this issue, see Monkkonen et al. (Citation2023b).

9 For suburban and rural jurisdictions, default densities may be as low as 10, 15, or 20 units per acre, depending on the location and population of the jurisdiction.

10 We selected median household income as a proxy for neighborhood opportunity.

11 Chula Vista’s low score may also reflect a less stringent HCD review for San Diego County jurisdictions, where housing elements were originally due before HCD published its current AFFH guidelines.

12 Cal. Gov. Code 65583(c).

13 Cal. Gov. Code 8899.5(a)(1).

References

- Baer, W. C. (1997). General plan evaluation criteria: An approach to making better plans. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369708975926

- Baer, W. (2008). California’s fair-share housing 1967–2004: The planning approach. Journal of Planning History, 7(1), 48–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513207307429

- Basolo, V. (1999). Passing the housing policy baton in the US: Will cities take the lead? Housing Studies, 14(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673039982713

- Berke, P. R. (1996). Enhancing plan quality: Evaluating the role of state planning mandates for natural hazard mitigation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 39(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640569612688

- Berke, P. R., & Godschalk, D. (2009). Searching for the good plan: A meta-analysis of plan quality studies. Journal of Planning Literature, 23(3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412208327014

- Berke, P. R., Smith, G., & Lyles, W. (2012). Planning for resiliency: Evaluation of state hazard mitigation plans under the Disaster Mitigation Act. Natural Hazards Review, 13 (2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000063

- California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. (2023). California incorporated cities. Shapefile. https://www.fire.ca.gov/what-we-do/fire-resource-assessment-program/gis-mapping-and-data-analytics

- California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). (2021a). Affirmatively furthering fair housing guidance for all public entities and for housing elements (April 2021 Update). California Department of Housing and Community Development. https://www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/affh/docs/AFFH_Document_Final_4-27-2021.pdf

- California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). (2021b). Regional housing needs allocation. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://www.hcd.ca.gov/planning-and-community-development/regional-housing-needs-allocation

- California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). (2023). Housing element compliance report. California Open Data Portal. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://data.ca.gov/dataset/housing-element-compliance-report

- City of Chula Vista. (2022). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Chula Vista. (2023). Chula vista districts and zones. Shapefile. https://chulavista-cvgis.opendata.arcgis.com/

- City of Culver City. (2021). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Downey. (2021). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Fontana. (2021). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Montebello. (2021). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Pasadena. (2022). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Santa Monica. (2021). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- City of Simi Valley. (2022). Housing element of the general plan 2021-2029.

- Clavel, P. (2011). What is the progressive city? Mimeo. https://hdl.handle.net/1813/40490

- Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). Affirmatively furthering fair housing rule guidebook. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Dillon, L. (2017). California lawmakers have tried for 50 years to fix the state’s housing crisis. Here’s why they’ve failed. The Los Angeles Times, June 29. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://www.latimes.com/projects/la-pol-ca-housing-supply/

- Dillon, L. (2022). Thousands of apartments may come to Santa Monica, other wealthy cities under little-known law. The Los Angeles Times, October 24. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2022-10-24/santa-monica-housing-apartment-boom

- Elder, K., Lo, L., & Freemark, Y. (2022). Homeownership in assessments of fair housing: Examining the use of homeownership-promoting strategies in local assessments of fair housing. The Urban Institute: Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center.

- Elmendorf, C. S., Biber, E., Monkkonen, P., & O’Neill, M. (2021). State Administrative Review of local constraints on housing development: Improving the California model. Arizona Law Review, 63, 609–677.

- Freemark, Y., Steil, J., & Thelen, K. (2020). Varieties of urbanism: A comparative view of inequality and the dual dimensions of metropolitan fragmentation. Politics & Society, 48(2), 235–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220908966

- Fulton, B., Garcia, D., Metcalf, B., Reid, C., & Braslaw, T. (2023). New pathways to encourage housing production: A review of California’s Recent Housing Legislation. A Terner Center Brief. UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

- Goetz, E. G. (2021). Democracy, exclusion, and white supremacy: How should we think about exclusionary zoning? Urban Affairs Review, 57(1), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419886040

- Goetz, E. G., Damiano, A., & Williams, R. A. (2019). Racially concentrated areas of affluence. Cityscape, 21(1), 99–124.

- GreenInfo Network. (2022). California protected areas database (Version 2022b). Geodatabase. https://www.calands.org/cpad/

- Guyadeen, D., & Seasons, M. (2018). Evaluation theory and practice: Comparing program evaluation and evaluation in planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 38(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16675930

- Haberle, M., Kye, P., & Knudsen, B. (2020). Reviving and improving HUD’s affirmatively furthering fair housing regulation: A practice-based roadmap. Poverty & Race Research Action Council. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28439

- Hannah-Jones, N. (2015). Living apart: How the government betrayed a landmark Civil rights law. Propublica, June 25.

- Jargowsky, P., Ding, L., & Fletcher, N. (2019). The Fair Housing Act at 50: Successes, failures, and future directions. Housing Policy Debate, 29(5), 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1639406

- Kahn, M. (2011). Do liberal cities limit new housing development? Evidence from California. Journal of Urban Economics, 69(2), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2010.10.001

- Kapur, S., Damerji, S., Elmendorf, C., & Monkkonen, P. (2021). What gets built on sites that cities “make available” for housing? UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies Policy Brief. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6786z5j9

- Lens, M., & Monkkonen, P. (2016). Do strict land use regulations make metropolitan areas more segregated by income? Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1111163

- Lewis, P. (2005). Can state review of local planning increase housing production? Housing Policy Debate, 16(2), 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2005.9521539

- Lyles, W., & Stevens, M. (2014). Plan quality evaluation 1994-2012: Growth and contributions, limitations, and new directions. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X14549752

- Manville, M. (2021). Liberals and housing: A study in ambivalence. Housing Policy Debate, 33(4), 844–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.1931933

- Manville, M., & Monkkonen, P. (2021). Unwanted housing: Localism and politics of housing development. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0739456X2199790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X21997903

- Menendian, S. (2017). Affirmatively furthering fair housing: A reckoning with government-sponsored segregation in the 21st century. National Civic Review, 106(3), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.21332

- Monkkonen, P., & Friedman, S. (2019). Not nearly enough: California lacks capacity to meet lofty housing goals. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies Policy Brief. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7t335284

- Monkkonen, P., Lens, M., O’Neill, M., Elmendorf, C., Preston, P., & Robichaud, R. (2023b). Do land use plans affirmatively further fair housing? Journal of the American Planning Association, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2023.2213214

- Monkkonen, P., Manville, M., & Friedman, S. (2019). A flawed law: Reforming California’s Housing Element. UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies Policy Brief. https://www.lewis.ucla.edu/research/flawed-law-reforming-california-housing-element/

- Monkkonen, P., Manville, M., Lens, M., Barrall, A., & Arena, O. (2023a). California’s Strengthened housing element law: Early evidence on higher housing targets and rezoning? Cityscape, 25(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/48736624

- Monkkonen, P., Manville, M., & Lens, M. (2024). Built out cities? A new approach to measuring land use regulation. Journal of Housing Economics, 63, 101982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2024.101982

- North, A. (2020). When Black lives matter protests come to “Copland”. Vox, July 9. https://www.vox.com/21310027/black-lives-matter-protest-2020-california-simi

- Norton, R. K. (2008). Using content analysis to evaluate local master plans and zoning codes. Land Use Policy, 25(3), 432–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.10.006

- O’Regan, K., & Zimmerman, K. (2019). The potential of the Fair Housing Act’s affirmative mandate and HUD’s AFFH rule. Cityscape, 21(1), 87–98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26608012

- Owens, A. (2019). Building inequality: Housing segregation and income segregation. Sociological Science, 6(19), 497–525. https://doi.org/10.15195/v6.a19

- Palm, M., & Niemeier, D. (2017). Achieving regional housing planning objectives: Directing affordable housing to jobs-rich neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(4), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1368410

- Ramsey-Musolf, D. (2016). Evaluating California’s housing element law, housing equity, and housing production (1990-2007). Housing Policy Debate, 26(3), 488–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2015.1128960

- Ramsey-Musolf, D. (2017a). State mandates, housing elements, and low-income housing production. Journal of Planning Literature, 32(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412217693569

- Ramsey-Musolf, D. (2017b). According to the plan: Testing the influence of housing plan quality on low-income housing production. Urban Science, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2010001

- Rothwell, J. T. (2011). Racial enclaves and density zoning: The institutionalized segregation of racial minorities in the United States. American Law and Economics Review, 13(1), 290–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/aler/ahq015

- San Diego County Assessor. (2023). Parcels. Shapefile. https://rdw.sandag.org/