ABSTRACT

This research investigates travel calculated hedonism (TCH) in diverse tourism contexts. An extant literature review, five focus groups and two expert panels conceptualised TCH. Field studies operationalised TCH in drinking (N = 355), eating (N = 351), wellness (N = 330) and shopping (N = 337) contexts. Findings identified four TCH scale dimensions – delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness. Theoretical definitions of TCH set the groundwork for rationalised binging that is cognitive- and affect-driven. The methodology presents an approach for a rigorous TCH measure. The TCH scale offers a tool for practitioners to design activities that instigate rationalised binging and responsible behaviour.

HIGHLIGHTS

The pursuit of calculated hedonism (PCH) in tourism contexts refers to a planned “let go” to “go all out” and “cram it all in” so as to responsibly actualise delayed rewards within the boundaries of a vacation.

Arguably, this is the first research to develop the four-factor PCH scale, which identified delayed rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness.

Conceptual and operational definitions for PCH set the theoretical groundwork for rationalised binging driven by a cognitive and affective search for delayed gratification.

The PCH scale offers a tool for practitioners to proactively design activities that instigate rationalised binging and responsible behaviour.

Introduction

The occurrence of “binge travel” or “revenge travel” post-COVID-19 highlights a rebound in travel behaviour to satisfy suppressed unfulfilled desires attributed to prior travel constraints (Lee et al., Citation2023). The intense desire to compensate for lost time has resulted in an unprecedented demand for and an unbridled splurge on hedonic travel offerings (Zhao & Liu, Citation2023). Countering this is travel calculated hedonism (TCH), which observes rationalised binging that sanctions planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours under pre-set conditions so as to responsibly attain delayed pleasurable rewards (Caluzzi et al., Citation2020; Featherstone, Citation2007). This phenomenon is borne from two opposing postmodern social movements – consumerism and social responsibility. The consumerism movement of the 1980s embraces Western consumer ideology, grounded in a social and economic framework, which encourages conspicuous and experiential consumption (Nixon & Gabriel, Citation2016). The movement endorses consumption desires that are fuelled by lifestyle obsessions rather than actual needs, resulting in a search for fulfilment through hedonic materialism (Crocket, Citation2016). Tourism presents as a medium to explore personal gains of health and well-being from hedonic experiences (Bhalla et al., Citation2021). In contrast, is the social responsibility movement of the 2000s, founded on an ethical framework that exacts accountability for performed actions (Nerone, Citation2002). This framework is underpinned by social norms that internalise moral obligations and conscientious actions (Chwialkowska, Citation2021). In tourism, actions by tourists take responsibility toward fulfilling a civic duty that benefits communities and the environment (Ahmad et al., Citation2023).

Grounded in the postmodern consumption theory of “bounded hedonistic consumption” and “rational hedonism,” calculated hedonism emerges. The phenomenon disrupts conventional hedonism arguments that pit emotions against rationality (e.g. Hirschman & Holbrook, Citation1982; Sood et al., Citation2021). Instead, it advocates an integrated form of search for sensory pleasure that is also rational (Featherstone, Citation2007; Stangl et al., Citation2023). This sets the stage for a transformative process that awakens moral consciousness in thinking, feeling and acting (Chhabra, Citation2021). Calculated hedonism sanctions rationalised binging in recreational situations, arguing that a plan to postpone gratification, and maximise compulsions under controlled conditions, constitutes deserving and responsible behaviour (Crocket, Citation2016). Thus, although boundaries are set on the act of consumption, hedonism is not forfeited as consumers proactively move across the different worlds of work obligations and social liberties (Fry, Citation2011). This underlines that compulsions for pleasure may be rationalised and justified in bounded leisure contexts (Brain, Citation2000; Szmigin et al., Citation2008).

Calculated hedonism is exemplified in recreational behaviour, such as binge reading, binge viewing and binge travelling. To illustrate, books proclaim “Why You Should Start Binge-Reading Right Now” (Dolnick, Citation2019). Likewise, streaming services publicise their content as the “Most Binge-Worthy TV” (Netflix, Citation2022). These claims extoll deferring unconstrained reading or viewing to a set time and place, wherein such behaviours may be maximised to their fullness for gratification. As the behaviours are calculated for ensuing hedonic outcomes, the binging sprees are seen to be deserving and worthy behaviour. Thus, in the tourism context, travel blogs dedicated to the “art of binge travelling” (Rajavelu, Citation2019) hype vacations as an “escape” because “we deserve it” (Wang et al., Citation2023).

In characterising TCH, this research concedes that the regular tourist and the calculated hedonic tourist share some similarities; yet are dissimilar in their intended actions and expected outcomes. Both cohorts are expected to delay gratification and make some sacrifices prior to a vacation. These sacrifices may involve setting aside finances, accruing leave from work, exercising to get physically fit and taking time to acquire knowledge for the vacation. However, while the regular tourist is likely to succumb to some spontaneous impulsive behaviour while on vacation, the calculated hedonic tourist plans to compulsively push their binging to the limits, but only for pre-determined stipulations within the vacation. This involves crossing financial, physical and psychological lines not normally breached within the routine of daily life, but responsibly doing so within set boundaries of the vacation.

Although calculated hedonism is conspicuous in postmodern society and acknowledged in the literature (e.Caluzzi et al., Citation2020; Szmigin et al., Citation2008), two key gaps are apparent. First, a definitive and common conceptualisation is lacking. This gap underlines the need to develop a conceptual definition of the phenomenon, particularly for experiential consumption in the burgeoning context of tourism post-COVID-19. Conceptualising TCH sets the theoretical groundwork for understanding rationalised binging in varied hedonic tourism experiences. Second, the mainly qualitative body of studies does not offer an operationalisation of the construct, let alone one in the context of tourism (e.g. Brain, Citation2000; Szmigin et al., Citation2008). Resultantly, no empirical scale exists to measure and predict TCH across diverse tourism contexts of experiential consumption. Development of such a scale lays the foundation for a methodology that rigorously evaluates TCH, benefitting theoretical underpinnings of rational hedonism. Further, the scale would serve as a managerial tool that guides tourism practitioners to identify calculated hedonic tourists and satisfy their compulsive desire for pleasure by creating activities that encourage responsible behaviour. In addressing the research gaps, this research sets out to conceptualise and operationalise TCH in the contexts of drinking, eating, wellness and shopping while travelling in Australia.

Literature review

Hedonism

Hedonism is derived from ancient Greek dialect where “hedone” was used to signify “pleasure (which includes the avoidance of pain) [as] the only good in life” (O’Shaughnessy & O’Shaughnessy, Citation2002, p. 526). From a postmodern perspective, Hirschman and Holbrook (Citation1982, p. 93) refer to hedonism as “multisensory images, fantasies and emotional arousal.” Further studies have elaborated that hedonism is propelled by a “search for happiness, fantasy, awakening, sensuality, and enjoyment” (To et al., Citation2007, p. 775).

In consumer studies, and critical to the hedonism construct, is the pursuit of pleasurable sensory stimulation that evokes positive emotions (Malone et al., Citation2014). Such studies have linked positive emotion and fantasy, with escapism from the routine of daily life (Nowell-Smith & Lemmon, Citation1960). In tourism studies, the ability to escape, find enjoyment or be entertained embodies hedonic value (Ji & Yang, Citation2022). Conversely, and also critical to the hedonism construct, is the avoidance of unpleasant sensory stimulation that deflects from negative emotions in undesirable outcomes (Leone et al., Citation2004). Negative emotions may also arise from unrealised hedonic experiences (Sood et al., Citation2021). Fuelled by a fear of missing out (FoMO), negative emotions of apprehension and regret result from not participating in an experience (Przybylski et al., Citation2013). Thus, tourists who experience travel FOMO from the constraints of COVID-19 are likely to make social comparisons and demonstrate envy toward unconstrained travellers (Xu et al., Citation2023). This instigates “revenge travel” behaviour to avoid further negative emotions (Lim et al., Citation2023). All these studies highlight the dyadic nature of hedonism that seeks pleasant and avoids unpleasant outcomes.

Binge behaviour

Consistent with the consumerism movement, binging manifests aspects of hedonism. Binging implies a loosened responsibility and freedom from social constraints to pursue unrestricted hedonic behaviour (Passini, Citation2013). Such behaviour is temporal, stimulated by situations, emotions and short-term disinhibition (Merikivi et al., Citation2018; Szmigin et al., Citation2008). Although the behaviour is transitory, it can occur in an intensive immersion state, often within a constructed reality (Agarwal & Karahanna, Citation2000).

Binging embodies characteristics of impulsive and compulsive behaviours (Ridgway et al., Citation2008). Each behaviour has received a different focus in tourism research. On the one hand, studies on impulsive travel behaviour mainly report the immediate and occasional unintended urges that stimulate positive emotions in on-the-spot travel consumption (e.g. Yao et al., Citation2021). Such studies highlight the lighter and more playful aspects of impulsive behaviour. On the other hand, studies on compulsive travel behaviour largely observe addictive, uncontrolled risk-taking and excessive urges, which result in negative emotions in the post-purchase (e.g. Koc, Citation2013; Stangl et al., Citation2023). Such studies underscore the darker and more serious aspects of compulsive behaviour. Collectively, these studies suggest that binge travel encapsulates impulsive and compulsive behaviours that result in positive and negative emotions.

Calculated hedonism

Calculated hedonism is underpinned by postmodern consumption theory that focuses on “bounded hedonistic consumption” and “rational hedonism” (Brain, Citation2000; Szmigin et al., Citation2008). According to Brain (Citation2000), bounded hedonism demonstrates a cognisance of limits and a conscious cost-benefit analysis for carving a psychoactive “time out” activity within the responsibility of life’s obligations (Fry, Citation2011). This signals a transformative process that awakens and transcends the self to a higher conscious state and purpose of life (Chhabra, Citation2021). In construing travel calculated hedonism (TCH), this research points to Hirschman’s and Holbrook (Citation1982) reference to Freud’s theory of personality. The theory identifies three perspectives in an individual’s personality: (1) the id as the rudimentary and instinctive self, wherein the individual is driven by emotions and pleasure in hedonism; (2) the superego as the critical and moralising self, wherein the individual functions as the rational and ethical thinker; and (3) the ego as the coordinated and realistic self, wherein the individual tempers instinctive desire with critical thinking. Freud’s ego clarifies TCH, which balances out the restraining obligations of everyday life with the unfettered hedonic travel pursuits, resulting in a planned release for a rationalised and bounded binging spree (Caluzzi et al., Citation2020; Featherstone, Citation2007). Consequently, this research observes that TCH encompasses several characteristics.

First, boundaries are drawn for when rationalised binging and its emotive rewards intersect and occur. These boundaries stipulate pre-set conditions for when TCH is allowed to take place responsibly (Brain, Citation2000; Szmigin et al., Citation2008). Thus, individuals pre-select specific time frames, social groups, environmental settings, spaces, activities and experiences where they permit themselves to binge responsibly on sensory experiences. All this infers that TCH sits in the nexus between reason and emotion (Crocket, Citation2016; Featherstone, Citation2007).

Second, in rationalised binging, present-time behaviours involve delaying gratification and even making sacrifices for future hedonic incentives (Bembenutty & Karabenick, Citation2004). To illustrate, in preparing for a vacation, individuals may need to put aside funds and annual leave as well as exercise for fitness and accumulate knowledge in order to reap the future hedonic rewards of the vacation. This behaviour is explained by delayed gratification theory, which describes a measured deferral of gratification to achieve future gains (Mischel & Ebbesen, Citation1970). In their experimental research, the authors have pointed out that individuals even occupy themselves with present-time behaviours to distract themselves from waiting for their reward. Importantly, individuals are more likely to delay their gratification if a present-time behaviour is framed positively and appeals to their better self, such as demonstrating environmental consciousness for the long-term rewards to themselves and their community (Arbuthnott, Citation2010).

Third, rationalised binging involves planned impulsiveness because there is deliberated behaviour toward being spontaneous in a projected future (Strack et al., Citation2006). This is explained by self-control theory, which is related closely to delayed gratification theory (Tangney et al., Citation2004). Self-control theory discerns the tension between affect-impetuous (i.e. spontaneous) and cognition-judicious (i.e. self-controlling) behaviours (Hoch & Loewenstein, Citation1991). The theory advocates that spontaneous behaviour is not necessarily irrational and “involves higher-order controlled cognitive process” (Miao, Citation2011, p. 84). This aligns with the notion that TCH involves behaviour that plans to be spontaneous (Strack et al., Citation2006) and is therefore, driven by both cognition and affect (Crocket, Citation2016; Featherstone, Citation2007).

Finally, rationalised binging incorporates planned compulsiveness as there is calculated behaviour toward fulfilling compulsive urges in a foreseeable future. Again, delayed gratification theory explains the deferred compulsive urges for gratification to realise future rewards (Mischel & Ebbesen, Citation1970). This subscribes to the view that TCH embodies behaviour that plans to be highly intense, excessive (Koc, Citation2013; Muller et al., Citation2005; Stangl et al., Citation2023) and driven by both reason and emotion (Crocket, Citation2016; Featherstone, Citation2007; Stangl et al., Citation2023).

From these characteristics, calculated hedonic tourists may be exemplified as those who plan financially, physically and mentally for taking a short wine-related vacation. Subsequently, they permit themselves to binge spontaneously and compulsively on wine, but only within the limits of the daily guided wine tours conducted by their tour operator, with a nominated set of friends and within the time frame of the vacation. Consequently, they perceive themselves to be undertaking deserving and responsible travel behaviour.

Methodology

The scale development of travel calculated hedonism (TCH) adopted a mixed-methods approach. This incorporated qualitative and quantitative research and followed procedures suggested by Churchill (Citation1995) and DeVellis (Citation2016), as seen in .

Figure 1. Scale development for TCH.

The qualitative research included an extant literature review, five focus groups and two expert panels. The quantitative research comprised four field studies and utilised a survey. This was self-administered to online consumer panels recruited through a professional data management company. Potential respondents were provided with a conceptual definition of TCH. They were screen for their prior experience with TCH, and whether they had taken such a vacation within the last 30 months. Participants were identified by a random identity number to ensure that they completed the online survey only once. As the survey did not allow for any incomplete sections, no issues of missing data were encountered. Each of the four field studies is detailed in the next section, and their demographic profiles seen in .

Table 1. Demographic profiles (Studies 1 to 4).

The qualitative and quantitative research followed ethical protocols from the researchers’ university (HRE2019–0242 and HRE2020–0032–01). The research sought informed participant approval from the focus groups, expert panels and field studies through an information sheet and consent form. These outlined the research objectives and anticipated outputs, and provided guarantees of voluntary participation, anonymity and confidentiality.

Scale development

Stage 1: Defining the construct

A multi-disciplinary literature review of behavioural psychology, psychiatry, sociology, marketing and tourism suggested that travel calculated hedonism (TCH), grounded in “rational hedonism” (Brain, Citation2000; Fry, Citation2011; Szmigin et al., Citation2008), encompasses delaying rewards (e.g. Arbuthnott, Citation2010; Bembenutty & Karabenick, Citation2004) as well as planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours (e.g. Edwards, Citation1993; Han et al., Citation1991). Having determined the three key behavioural characteristics of TCH, a working definition was framed as “A planned push beyond a tourist’s usual financial, physical and time limits to attain deserved emotional fulfilment within the short time frame of a vacation.” This working definition was presented to five focus groups for their comments. Consequently, their inputs provided the foundations for conceptualising TCH as:

A planned push beyond a tourist’s usual financial, physical and time limits to attain deserved emotional fulfilment within the short time frame of a vacation. It is a deliberated action by the tourist to responsibly “let go” so as to “go all out” and “cram it all in.”

Stage 2: Generating scale items

The extant literature review identified scale items that had potential to represent travel calculated hedonism (TCH). This meant assessing and adapting existing scale items that tapped into delaying rewards as well as planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours for their relevance to the tourism context. The process generated a preliminary set of 42 scale items for the TCH scale.

Five focus groups (N = 43) comprising working Australians from a cross-section of ages, genders, education, occupations and incomes, who had propensity to engage in TCH while on vacation were recruited. The focus groups were convened with three outcomes in mind. First, participants reviewed and commented on the conceptual definition of TCH. Their inputs with phrases, such as “let go,” “go all out,” and “cram it all in” were included in the conceptual definition of TCH, which was identified in stage one of the scale development. Second, they offered suggestions of tourism contexts where it was likely to occur. The top four tourism contexts that were selected included drinking, eating, wellness and shopping. These four tourism contexts were used as the basis for the four field studies. Third, participants assessed the relevance of the initial set of 42 scale items and added their own input. They then were asked to consider each scale item, and items that had a majority vote for being “Appropriate” (i.e. over 60%), such as “show iron resolve in my prep for the vacation,” “let loose when the mood takes me,” “spending more than intended” and “starting early for the day and/or finishing late” were retained. Consequently, six scale items were deleted because they were viewed to be similar or ambiguous, resulting in 36 scale items.

Two expert panels (N = 10) constituting industry experts and research academics with interests in tourism and consumer buying behaviour were engaged. Panellists appraised the conceptual definition of TCH and endorsed the four tourism contexts of drinking, eating, wellness and shopping where it was likely to take place. They also examined the 36 scale items and suggested an additional six scale items. Once again, scale items with an “Appropriate” vote that exceeded 60% were accepted. As a result, 18 items deemed to be vague or duplicating were eliminated, leading to 24 scale items that showed content validity.

Stage 3: Purifying scale items

Study 1: Drinking

The 24 scale items that represented travel calculated hedonism (TCH) were introduced to the survey instrument for Study 1. This sampling frame was targeted for their past experience with planned, binge-drinking-related activities while on vacation. Such activities were described as wine tours, beer and cider tours as well as wine appreciation workshops.

In total, 355 completed responses were elicited for Study 1. The 24 scale items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using an Oblimin rotation with SPSS 29. As seen in , the final solution established 15 scale items and four factors, which identified delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness. This solution explained 81% of the total variance, with the KMO MSA at 0.84 and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity at 0.01. We now make mention that the 12-item scale that represents the four dimensions of travel calculated hedonism can be seen in the Appendix. Cronbach alpha scores for the four TCH factors ranged from 0.86 to 0.93, exhibiting their reliability (Nunnally, Citation1994).

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis for the TCH factors (Study 1).

Stage 4: Refining scale items

Study 2: Eating

The survey instrument in Study 2, which included the 15 scale items for pursuing travel calculated hedonism (TCH) was self-administered to a sampling frame that had prior experience with planned, binge-eating-related activities while on vacation. These activities were characterised as food tours, food samplings, degustation meals and cooking workshops.

Study 2 obtained 351 completed responses. This time, two-step confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS 29 was run, following procedures suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) as well as Baumgartner and Homburg (Citation1996), to validate the 15 scale items and four factors that represented TCH. The sample was split at random in two parts. The initial part of the split sample (N = 100) was used in the first step of CFA to determine the underlying factor structures of the TCH scale. The second part of the split sample (N = 251) was utilised in the second step of CFA to establish model fitness.

In the first step of CFA, one-factor congeneric models with AMOS 29 were administered to each of the four TCH factors that included delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness. Model fit was assessed by the goodness-of-fit indices (χ2/df ≤3.0; p ≥ 0.05; RMSEA ≤ 0.08; CFI ≥ 0.90; NFI ≥ 0.90; GFI ≥ 0.90) (Hair et al., Citation2019). The resultant 12 scale items represented the four TCH factors as seen in .

Table 3. Goodness-of-fit indices for the TCH factors (Study 2).

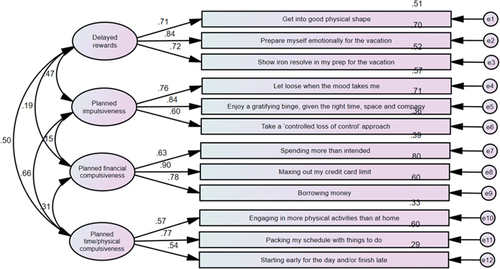

The second step of CFA introduced the 12 scale items in a measurement model using the maximum likelihood estimation method with AMOS 29. As seen in , all parameter estimates ranged from 0.54 to 0.90, exceeding 0.50, deemed to be at the lower end of acceptability (Hair et al., Citation2019). Further, the goodness-of-fit indices for the measurement model fulfilled the critical criteria (χ2/df = 2.30; p = 0.01; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.94; NFI = 0.90; GFI = 0.93) (Joreskog & Sorbom, Citation1996). For these reasons, the four-factor TCH scale was found to have an appropriate fit.

Figure 2. Measurement model for TCH (Study 2).

The composite reliability (CR) for each of the four TCH factors were estimated from structural equation modelling procedures implemented in the measurement model. The CR scores for the TCH factors ranged from 0.66 to 0.82, surpassing 0.60, assessed to be at the lower end of reliability (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Stage 5: Validating scale items

Study 3: Wellness

The survey instrument in Study 3 that comprised the 12 scale items for travel calculated hedonism (TCH) targeted a sampling frame for their previous experience with planned, binge-wellness-related activities while on vacation. Such activities were exemplified as spa treatments, yoga retreats, meditation and fitness.

Study 3 collected 330 completed responses. The sample was randomly split in two parts. The initial part of the split sample (N = 100) was utilised to confirm the factor structures of the TCH scale. The second part of the split sample (N = 230) was used to determine whether the TCH factors had appropriate model fitness, reliability as well as convergent, discriminant and predictive validity.

The four factors and 12 scale items that represented TCH were subjected to two-step confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS 29. The analysis confirmed that the factor structures and scale items were consistent with those identified in Studies 1 and 2. As seen in , the composite reliability (CR) for the four TCH factors ranged from 0.68 to 0.82, suggesting acceptable reliability (Hair et al., Citation2019).

Table 4. Composite reliabilities, average variance extracted scores and correlations of the TCH factors (Study 3).

Two tests evaluated the convergent validity of the four TCH factors. First, the AVE scores must be adequate (≥ 0.50) (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The AVE scores for three TCH factors ranged from 0.57 to 0.62, as seen in . An exception was the planned impulsiveness factor, which had an AVE score of 0.41. Nevertheless, an AVE score of over 0.40 is deemed to be at the lower end of acceptability under the condition that the CR score is above 0.60 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Lam, Citation2012). As the CR score for the planned impulsiveness factor was 0.68, this supported convergent validity. Second, the correlation coefficient between the TCH factors and an existing relevant scale must be significant (p ≤ 0.05). As seen in , delaying rewards and Tangney, Baumeister and Boone’s (Citation2004) self-control scale correlated at 0.66 (p ≤ 0.01). Planned impulsiveness and Han et al. (Citation1991) planned impulsive buying scale correlated at 0.59 (p ≤ 0.01). Planned financial compulsiveness and Edwards (Citation1993) compulsive buying scale correlated at 0.62 (p ≤ 0.01). Planned time/physical compulsiveness and Edwards (Citation1993) compulsive buying scale correlated at 0.49 (p ≤ 0.01). These two tests supported convergent validity for the four factors.

Table 5. Correlations between the developed TCH scale and existing scales (Study 3).

Two tests considered the discriminant validity of the four TCH factors. First, the AVE scores between two constructs should be greater than the square of the correlations between them (Hair et al., Citation2019). The AVE scores for the TCH factors ranged from 0.41 to 0.62, surpassing the squared correlations between any two factors, which ranged from 0.06 to 0.21, as seen in . Second, the correlation between any two factors must be low (≤ 0.80) (Bagozzi & Heatherton, Citation1994). The correlations between the four TCH factors ranged from 0.26 to 0.45. These two tests supported discriminant validity for the four factors.

Study 4: Shopping

Study 4 re-introduced the 12 scale items for travel calculated hedonism (TCH) into the survey, which was self-administered to a sampling frame that had past experience with planned, binge-shopping-related activities while on vacation. These activities were referred to as shopping tours, bulk buying souvenirs and bulk buying during sales.

In sum, 337 completed responses were acquired for Study 4. Two-step confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS 29 validated the 12 scale items and four factors that represented TCH. As with Studies 1, 2 and 3, the composite reliability (CR) for the four TCH factors showed acceptable reliability (≥0.60) and demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2019).

As part of the scale item validation in stage five of the scale development, establishing nomological validity was required. This explored the ability of the TCH factors to predict a dependent variable. Intention or the tendency towards an action is commonly used as a dependent variable in tourism studies (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2012; Lim et al., Citation2023). Linear regression with SPSS 29 determined the nomological validity of the TCH factors in predicting intention to engage in a planned, binge-wellness-related vacation. The intention construct was measured by Kim et al. (Citation2012) four-item scale. As seen in , delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness all produced significant and positive impacts on intention (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 6. Predictive validity of the TCH scale factors on intention (Study 4).

Stage 6: testing measurement invariance (Studies 1 to 4)

Finally, structural equation modelling (SEM) using multigroup analysis with AMOS 29 estimated whether the travel calculated hedonism (TCH) scale had measurement invariance. This was undertaken with the pooled sample from the four main studies (N = 1,373). The gender variable was selected to examine whether the TCH scale was invariant across groups. Gender is commonly used in measurement invariance testing (e.g. Dong & Dumas, Citation2020), justifying its selection in this research.

From the pooled sample, two distinct groups were identified – female (N = 750) and male (N = 621). Only one respondent identified as non-binary in the third gender category (other) and one respondent did not select a gender category. Due to the large comparable sample sizes identified in the female and male groups, the two groups were used in comparative tests for measurement invariance across groups.

Measurement invariance was assessed with three tests. The first test was for configural invariance. In this test, a fully unconstrained measurement model (M1) was identified. This model incorporated the 12 scale items and their respective latent variables identified in Studies 1 to 4. As seen in , the unconstrained model (M1) met the goodness-of-fit indices (χ2/df = 3.57; p = 0.01; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.96). An exception was the χ2/df, which was above 3.0. However, given the large sample size (≥750), which has a tendency to inflate the normed chi square score and the other acceptable goodness-of-fit indices, the model fit was found to be appropriate (Hair et al., Citation2019). This underlined that the TCH scale items and factors remained unchanged across the gender groups, implying configural invariance for the TCH scale across the groups.

Table 7. Measurement invariance of the TCH scale (Studies 1 to 4).

Having verified configural invariance, the second test was for full metric invariance. In this test, the standardised regression weights between the 12 scale items and their respective latent variable were constrained. This model (M2) was compared with the configural model (M1). The Δχ2 and Δdf were 12.4 and 12 respectively, with a non-significant p-value of 0.43, and the goodness-of-fit indices fulfilled the critical thresholds (χ2/df = 3.29; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.96), as seen in . Although the χ2/df was marginally over 3.0, it is permissible when taking into account the large sample size (≥750) and other appropriate goodness-of-fit criteria (Hair et al., Citation2019). This highlighted that the TCH scale items and factors were measurably consistent across the gender groups, suggesting that full metric invariance was supported for the TCH scale across the groups.

In ascertaining configural and metric invariance, the third test was for full factor variance invariance. In this test, the unconstrained configural model was revisited and each latent variable was constrained. This model (M3) was compared with the configural model (M1). As seen in , the Δχ2 and Δdf were 2.85 and 4 respectively, with a non-significant p-value of 0.58, and the goodness-of-fit indices showed appropriateness in the model fit (χ2/df = 3.46; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.96). While an exception was the χ2/df, which sat above 3.0, it was justified by the large sample size (≥750) and other goodness-of-fit indices (Hair et al., Citation2019). This showed that the TCH scale factors remained unchanged across the gender groups, inferring factor variance invariance for the TCH scale across the groups.

Conclusion

Discussion

This research set out to clarify and build understanding of travel calculated hedonism (TCH). An extant literature review examined conceptualisations of hedonism, binge behaviour and calculated hedonism to arrive at a conceptual definition relevant to the tourism context. Then, five focus groups and two expert panels concurred on the conceptualisation of TCH as a planned “let go” to “go all out” and “cram it all in” so as to responsibly actualise delayed rewards within the boundaries of a vacation.

The research also set out to operationalise TCH by developing a scale that was stringently tested and validated across the contexts of drinking, eating, wellness and shopping while travelling. The 12-item scale identified the four dimensions of delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness, as seen in the Appendix. The scale demonstrated reliability, content, convergent, discriminant and nomological validity as well as measurement invariance.

Theoretical and methodological implications

This research contributes to theoretical and methodological discussions related to travel calculated hedonism (TCH) in four primary ways. First, it offers a conceptualisation of TCH in the tourism context that is meticulously derived from qualitative research. Clarification of TCH, currently lacking in the literature, has scope to provide the theoretical groundwork for its application in niche tourism sectors, such as ecotourism, heritage tourism or luxury tourism.

Second, the conceptualisation of TCH theoretically differentiates the regular tourist from the calculated hedonic tourist. A tourist is described as a “person at leisure who also travels” (Nash et al., Citation1981, p. 462) and may indulge in some impulsive behaviour (Miao, Citation2011). Conversely, the calculated hedonic tourist demonstrates a purposeful agenda, which pushes beyond their usual financial, physical and time limits, for a binging spree that delivers deserving emotional fulfilment under responsible and pre-set conditions. The rationalised and bounded binging to “let go,” “go all out” and “cram it all in” with sensory experiences is what sets the calculated hedonic tourist apart from the regular tourist.

Third, the empirical TCH scale, rigorously developed from quantitative research, offers the methodological foundation to measure calculated hedonism in tourism and recreational scenarios. For instance, with adaptations to the 12 scale items, the instrument may be extended to contexts related to fitness (Brown et al., Citation2017) or luxury getaways (Wang et al., Citation2023). In these contexts, it would be pertinent to explore why individuals delay gratification by making sacrifices in exercising (i.e. “no pain, no gain”) or spending (i.e. saving for a getaway) for future pleasurable rewards.

Further, the TCH scale differentiates from other scales related to delayed gratification (e.g. Arbuthnott, Citation2010; Bembenutty & Karabenick, Citation2004) as well as planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours (e.g. Edwards, Citation1993; Han et al., Citation1991). Unlike these individual and disparate scales, the TCH scale integrates measures of delaying rewards with planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours. The result is a seamless 12-item instrument with sound psychometric properties of reliability, validity and measurement invariance for the purpose of advancing quantitative research.

Practical implications

This research also contributes to the managerial practices related to travel calculated hedonism (TCH) in two main ways. First, the 12-item TCH scale is an easy tool for practitioners to implement in surveys. Once a travel booking is made, the survey could function as a furthered engagement point, administered as an invited text or email with the confirmed booking. Notably, such survey invitations should only be sent after an initial engagement as ad-hoc surveys may be perceived as spam (Douglas, Citation2015). The pre-vacation survey could assess tourists’ propensity for TCH and their expectations of deserving and responsible sensory experiences. This could guide practitioners to develop and present offerings that meet or better still, exceed expectations. Alternatively, the survey could be implemented post-vacation with an optional survey link that complements a customer satisfaction survey. This could assist practitioners in predicting revisit intention and future engagement in TCH-related activities.

Second, practitioners may use the TCH scale to profile calculated hedonic tourists according to the four dimensions of delaying rewards, planned impulsiveness, planned financial compulsiveness and planned time/physical compulsiveness. To illustrate, one group may identify with delaying rewards and planned impulsiveness and be named “calculated impulse seekers,” another with delaying rewards and planned financial compulsiveness and be labelled as “calculated spenders” and yet another with delaying rewards and planned time/physical compulsiveness and be identified as “calculated crammers.” Clearly, there is need to develop and target specific offerings for each profile. Presumably, “calculated impulse seekers” would have a preference to “let loose when the mood takes [them],” “enjoy a gratifying binge given the right time, space and company” and “take a ‘controlled loss of control’ approach.” As an example, operators of the “Bargains and Bubbles” tour in the Melbourne Shopping Experience (Citation2024), which promises a “relaxed and fun day of discount retail therapy” and the opportunity to “shop till you drop” (www.melbourneshoppingexperiences.com.au/) would best target their communications to “calculated impulse seekers.”

Limitations and future research

Three main limitations are identified in this research. First, the research is limited by its sample size. While the four field studies comprised 1,373 responses collectively, each individual study averaged a relatively small sample size (N = 343). This potentially reduces the generalisability of the findings. However, it has been argued that sample sizes of at least 300 are usually sufficient in scale development (Worthington & Whittaker, Citation2006), justifying the research methodology. Still, in further investigations, the sample size could be increased to broaden the applicability of the research.

Second, the sampling frame is a constraint in the research. The four field studies were solicited from an Australian adult sample. This restricts the use of the research on a global scale. Despite this, the sampling frame did address the research objectives of conceptualising and operationalising travel calculated hedonism (TCH) with empirical procedures. Nevertheless, there is need to implement the TCH scale in other countries, such as China and USA with large consumerist populations, to assess its global relevance and substantiate its generalisability.

Third, the research is delimited by its focus on four contexts, namely, drinking, eating, wellness and shopping while travelling. This narrows the research scope, leaving it untested in the broader spectrum of recreational contexts, such as responsible gambling (Gray et al., Citation2021). However, it should be pointed out that the four tourism contexts were identified as the most popular scenarios by focus groups and endorsed by expert panels in the qualitative research, which led to their selection. Notwithstanding, future quantitative research would benefit from new contexts to validate the generalisability of the TCH scale.

Presently, TCH has been explored in lighter contexts of drinking, eating, wellness and shopping while travelling. In these contexts, it may be argued that rationalised binging seeks to actualise delayed hedonic rewards that are “naughty but nice” and generally, sanctioned by mainstream society. In progressing the research area, there is need to investigate TCH in darker tourism contexts, such as gambling (Greenwood & Dwyer, Citation2017), casual sex encounters (Omondi & Ryan, Citation2017) or cosmetic medical tourism (Sood et al., Citation2021). In these contexts, it may be conjectured that rationalised binging looks to realise delayed hedonic rewards that are “dark and dangerous” and largely, unsanctioned by mainstream society. It would be interesting to test whether planned impulsiveness emerges as the strongest indicator in “naughty but nice” contexts and planned compulsiveness in “dark and dangerous” contexts. Such insights could prove critical in guiding policy that deals with TCH expectations and behaviour in respective tourism settings.

In sum, TCH, conspicuous in post-COVID-19 societies, describes rationalised binging that sanctions planned impulsive and compulsive behaviours under bounded conditions in delayed gratification. The conceptualisation of TCH sets the theoretical groundwork for an understanding of rational hedonism that is driven by a cognitive and affective pursuit of future pleasurable rewards. The operationalisation of TCH introduces an empirical methodology to develop a reliable and valid measure of rationalised binging. The four-factor, 12-item TCH scale offers a tool for practitioners to proactively design activities that instigate rationalised binging and responsible behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agarwal, R., & Karahanna, E. (2000). Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Quarterly, 24(4), 665–694. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250951

- Ahmad, N., Samad, S., & Han, H.-S. (2023). Travel and tourism marketing in the age of the conscious tourists: A study on CSR and tourist brand advocacy. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(7), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2276433

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arbuthnott, K. D. (2010). Taking the long view: Environmental sustainability and delay of gratification. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01196.x

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self-esteem. Structural Equation Modelling, 1(1), 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519409539961

- Baumgartner, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modelling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(95)00038-0

- Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (2004). Inherent association between academic delay of gratification, future time perspective, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 16(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000012344.34008.5c

- Bhalla, R., Chowdhary, N., & Ranjan, A. (2021). Spiritual tourism for psychotherapeutic healing post COVID-19. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1930630

- Brain, K. (2000). Youth, alcohol and the emergence of the post-modern alcohol order. Institute of Alcohol Studies. http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/IAS%20reports/brainpaper.pdf

- Brown, T. C., Miller, B. M., & Adams, B. M. (2017). What’s in a name? Group fitness class names and women’s reasons for exercising. Health Marketing Quarterly, 34(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2017.1309212

- Caluzzi, G., MacLean, S., & Pennay, A. (2020). Re-configured pleasures: How young people feel good through abstaining or moderating their drinking. International Journal of Drug Policy, 77, 102709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102709

- Chhabra, D. (2021). Transformative perspectives of tourism: Dialogical perceptiveness. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1986197

- Churchill, G. A. (1995). Marketing research methodological foundations (6th ed.). Dryden Press.

- Chwialkowska, A. (2021). Money and status or clear conscience and clean air – should we vary the marketing interventions depending on tourist’s cultural background? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1875106

- Crocket, H. (2016). An ethic of indulgence? Alcohol, ultimate frisbee and calculated hedonism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(5), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214543960

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications.

- Dolnick, B. (2019). Why You Should Start Binge Reading Right Now. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/04/opinion/sunday/why-you-should-start-binge-reading-right-now.html

- Dong, Y.-X., & Dumas, D. (2020). Are personality measures valid for different populations? A systematic review of measurement invariance across cultures, gender, and age. Personality and Individual Differences, 160(1), 109956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109956

- Douglas, T. (2015). Why Marketers Should Stop Sending Spam Surveys. Linkedin. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-marketers-should-stop-sending-spam-surveys-tyler-douglas

- Edwards, E. A. (1993). Development of a new scale for measuring compulsive buying behaviour. Financial Counselling and Planning, 4(1), 67–84.

- Featherstone, M. (2007). Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. SAGE.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Fry, M.-L. (2011). Seeking the pleasure zone: Understanding young adult’s intoxication culture. Australasian Marketing Journal, 19, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2010.11.009

- Gray, H. M., Louderback, E. R., LaPlante, D. A., Abarbanel, B., & Bernhard, B. J. (2021). Gamblers’ beliefs about responsibility for minimizing gambling harm: Associations with problem gambling screening and gambling involvement. Addictive Behaviours, 114, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106660

- Greenwood, V. A., & Dwyer, L. (2017). Reinventing Macau tourism: Gambling on creativity? Current Issues in Tourism, 20(6), 580–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1187585

- Hair, J. F., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2019). Essentials of business research methods (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Han, Y.-K., Morgan, G. A., Kotsiopulos, A., & Kang-Park, J.-K. (1991). Impulse buying behaviour of apparel purchasers. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 9(3), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X9100900303

- Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. The Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600314

- Hoch, S. J., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1991). Time-inconsistent preferences and consumer self-control. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1086/208573

- Ji, C.-L., & Yang, P. (2022). What makes integrated resort attractive? Exploring the role of experience encounter elements. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 39(3), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2022.2089952

- Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1996). LISREL8: User’s reference guide. Scientific Software.

- Kim, M.-J., Lee, M.-J., Lee, C.-K., & Song, H.-J. (2012). Does gender affect Korean tourists’ overseas travel? Applying the model of goal-directed behaviour. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 17(5), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.627355

- Koc, E. (2013). Inversionary and liminoidal consumption: Gluttony on holidays and obesity. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(8), 825–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.835669

- Lam, L. W. (2012). Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1328–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026

- Lee, K.-M., Kim, M.-S., Kim, J.-Y., & Koo, C.-M. (2023). Exploring a pent-up travel: constraint-negotiation model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(4), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2245415

- Leone, L., Perugini, M., & Ercolani, A. (2004). Studying, practicing, and mastering: A test of the model of goal-directed behaviour (MGN) in the software learning domain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(9), 1945–1973. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02594.x

- Lim, W. M., Sahoo, S., Agrawal, A., & Vijayvargy, L. (2023). Fear of missing out and revenge travelling: The role of contextual trust, experiential risk, and cognitive image of destination. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(7), 583–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2276431

- Malone, S., McCabe, S., & Smith, A. P. (2014). The role of hedonism in ethical tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.10.005

- Melbourne Shopping Experience. (2024). Melbourne’s Best Shopping Tours. Retrieved January 8, 2024, from https://www.melbourneshoppingexperiences.com.au/

- Merikivi, J., Salovaara, A., Mäntymäki, M., & Zhang, L.-L. (2018). On the way to understanding binge watching behaviour: The over-estimated role of involvement. Electronic Markets, 28(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-017-0271-4

- Miao, L. (2011). Guilty pleasure or pleasurable guilt? Affective experience of impulse buying in hedonic-driven consumption. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 35(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010384876

- Mischel, W., & Ebbesen, E. B. (1970). Attention in delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16(2), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029815

- Muller, A., Reinecker, H., Jacobi, C., Reisch, L., & de Zwaan, M. (2005). Pathological buying – a literature review. Psychiatrische Praxis, 32(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-814965

- Nash, D., Akeroyd, A. V., Bodine, J. J., Cohen, E., Dann, G., Graburn, N. H. H., Hermans, D., Kemper, R. V., LaFlamme, A. G., Manning, F., Noronha, R., Pi-Sunyer, O., Smith, V. L., Stoffle, R. W., Thurot, J. M., Watson-Gegeo, K. A., & Wilson, D. (1981). Tourism as an anthropological subject [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, 22(5), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1086/202722

- Nerone, J. C. (2002). Social responsibility theory. In D. McQuail (Ed.), Mcquail’s reader in mass communication theory (pp. 183–193). Sage Publications.

- Netflix. (2022). Most Binge-Worthy TV Shows. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.netflix.com/au/browse/genre/1191605

- Nixon, E., & Gabriel, Y. (2016). So much choice and no choice at all: A socio-psychoanalytic interpretation of consumerism as a source of pollution. Marketing Theory, 16(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593115593624

- Nowell-Smith, P. H., & Lemmon, E. J. (1960). i.—escapism: The logical basis of ethics. Mind, LXIX(275), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LXIX.275.289

- Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E. Tata McGraw-Hill Education.

- O’Shaughnessy, J., & O’Shaughnessy, N. J. (2002). Marketing, the consumer society and hedonism. European Journal of Marketing, 36(5/6), 524–547. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560210422871

- Omondi, R. K., & Ryan, C. (2017). Sex tourism: Romantic safaris, prayers and witchcraft at the Kenyan coast. Tourism Management, 58, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.003

- Passini, S. (2013). A binge-consuming culture: The effect of consumerism on social interactions in western societies. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13489317

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioural correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behaviour, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

- Rajavelu, N. (2019). Travel Tear. The Art of Binge Traveling. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from. https://traveltear.com/the-art-of-binge-travelling-explained/1735/

- Ridgway, N., Kukar-Kinney, M., & Monroe, K. B. (2008). An expanded conceptualisation and a new measure of compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1086/591108

- Sood, A., Quintal, V., & Phau, I. (2021). Through the looking glass: Perceiving risk and emotions toward cosmetic procedure engagement. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(1), 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2020-0473

- Stangl, B., Kastner, M., Park, S.-W., & Ukpabi, D. (2023). Internet addiction continuum and its moderating effect on augmented reality application experiences: Digital natives versus older users. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2199776

- Strack, F., Werth, L., & Deutsch, R. (2006). Reflective and impulsive determinants of consumer behaviour. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1603_2

- Szmigin, I., Griffin, C., Mistral, W., Bengry-Howell, A., Weale, L., & Hackley, C. (2008). Re-framing ‘binge drinking’ as calculated hedonism: Empirical evidence from the UK. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19(5), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.08.009

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

- To, P.-L., Liao, C.-C., & Lin, T.-H. (2007). Shopping motivations on internet: A study based on utilitarian and hedonic value. Technovation, 27(12), 774–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2007.01.001

- Wang, X., Lai, I. K.-W., & Wang, X.-Y. (2023). The influence of girlfriend getaway luxury travel experiences on women’s subjective well-being through travel satisfaction: A case study in Macau. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 55, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.03.004

- Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counselling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

- Xu, J., Wang, Y., & Jiang, Y.-Y. (2023). How do social media tourist images influence destination attitudes? Effects of social comparison and envy. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2245410

- Yao, Y.-B., Jia, G.-M., & Hou, Y.-S. (2021). Impulsive travel intention induced by sharing conspicuous travel experience on social media: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 49, 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.10.012

- Zhao, S.-S., & Liu, Y.-F. (2023). Revenge tourism after the lockdown: Based on the SOR framework and extended TPB model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(5), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2256777

Appendix

Screening Questions

On a previous vacation, I have engaged in planned, binge-[nominated tourism context]. Yes/No.

The last time I engaged in a planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation was:

Less than 17 months ago

18–23 months ago

2–2.4 years ago

More than 2.5 years ago

Scale items for travel calculated hedonism (TCH) factors

Delaying Rewards

BEFORE my planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation, I plan to:

Put aside funds and save up

Allocate days off to go on vacation

Accumulate knowledge about the vacation and its activities

Get into good physical shape*

Prepare myself emotionally for the vacation*

Show iron resolve in my prep for the vacation*

Planned Impulsive Behaviour

DURING my planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation, I plan to:

Allow myself to go on a spontaneous spree

Let loose when the mood takes me*

Pack my schedule tight and just let go

Enjoy a gratifying binge, given the right time, space and company*

Take a “controlled loss of control” approach*

Go all out and cram it all in

Planned Compulsive Behaviour (Financial)

I plan to push BEYOND MY FINANCIAL limits while on a planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation by:

Spending more than intended*

Going on a buying spree

Maxing out my credit card limit*

Borrowing money*

Planned Compulsive Behaviour (Physical)

I plan to push BEYOND MY PHYSICAL limits while on a planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation by:

Sleeping less than normal

Engaging in more physical activities than at home*

Packing my schedule with things to do*

Going beyond my usual physical endurance

Planned Compulsive Behaviour (Time)

I plan to push BEYOND MY TIME limits while on a planned, binge-[nominated tourism context] vacation by:

Rushing to accommodate more activities

Going on longer tours

Pushing beyond time constraints

Starting early for the day and/or finishing late*

Note: All scale items are measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale

* denotes the final scale items