ABSTRACT

Background

Perpetrating or witnessing acts that violate one's moral code are frequent among military personnel and active combatants. These events, termed potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), were found to be associated with an increased risk of depression, in cross-sectional studies. However, the longitudinal contribution of PMIEs to depression among combatants remains unclear.

Method

Participants were 374 active-duty combatants who participated in a longitudinal study with four measurement points: T1-one year before enlistment, T2-at discharge from army service, and then again 6- and 12-months following discharge (T3 and T4, respectively). At T1, personal characteristics assessed through semi-structured interviews. At T2-T4, PMIEs and depressive symptoms were assessed.

Results

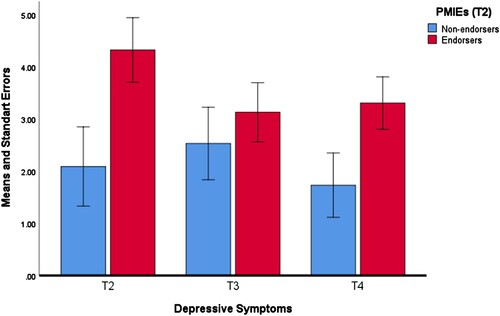

At discharge (T2), a total of 48.7% of combatants reported experiencing PMIEs incident, compared with 42.4% at T3 and 30.7% at T4. We found a significant interaction effect in which combatants endorsing PMIEs at discharge reported higher severity of depression symptoms at discharge (T2) than combatants who reported no PMIEs. This effect decreased over time as depression levels were lower at T3 and T4.

Conclusions

PMIE experiences, and especially PMIE-Betrayal experiences, were found to be valid predictors of higher severity of depression symptoms after the first year following discharge.

Introduction

Military combatants often face potentially traumatic events that place them at risk for long-term mental health disorders, such as depression and PTSD (Arditte Hall et al., Citation2019; Hassija et al., Citation2012; Snir et al., Citation2017). It has been well-established that combat trauma produces a long-term negative effect on psychopathology and mental pain (McCabe et al., Citation2020) in both cross-sectional (e.g., Bartone & Homish, Citation2020) and longitudinal (e.g., Walker et al., Citation2021) studies.

Engaging in modern warfare and guerilla combat within a civilian setting exposes combatants to severe moral and ethical challenges. Whereas most of these challenges are handled effectively, some potentially moral injuries events (PMIEs), such as direct perpetration, failing to prevent, and witnessing immoral acts, contravene deeply held moral beliefs and may have deleterious psychological effects (Litz et al., Citation2009). A formal measure, the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES; Nash et al., Citation2013), has been validated to examine PMIEs, and factor analyses have identified three subscales: transgressions by self, transgressions by others, and betrayal (Bryan et al., Citation2016). Several studies in this emerging research domain indicate that PMIEs are common among combatants: Although the frequency of PMIEs tends to vary by era, nature of war, and armies, more than one-third of active-duty combatants and veterans report exposure to at least one type of PMIE (Griffin et al., Citation2019).

Litz et al.’s (Citation2009) conceptual model suggests that exposure to PMIEs during military service may cause significant moral dissonance among veterans, which, if left unresolved, could lead to moral pain and psychopathologies (Farnsworth et al., Citation2017; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that exposure to PMIEs can lead to increased vulnerability to psychiatric symptomatology, such as depression symptoms and suicidal ideation (McEwen et al., Citation2021; Williamson et al., Citation2018). Importantly, however, these studies’ contributions notwithstanding, their findings are tempered by their cross-sectional design. None of these studies examined the term effects of exposure to PMIEs on psychopathology in general, specifically on depressive symptoms and the course of symptoms over time. Interestingly, although the risk for depression following combat trauma (unrelated to PMIEs) is higher among combat veterans (e.g., Bonde et al., Citation2016; Ginzburg et al., Citation2010), several studies examining the course of symptoms following traumatic events have found a steady decrease in the severity of depressive symptoms over time (e.g., Arditte Hall et al., Citation2019). However, it remains an open question whether depression levels will decrease one year following discharge in relation to PMIE exposure during military service.

The present study

In this study, we aimed to narrow the knowledge gap regarding the influence of exposure to PMIEs on depressive symptoms among army veterans. To do so, we examined the enduring contribution of such an exposure to depressive symptoms among combat veterans in their first year following their discharge from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). This time frame is known as highly challenging, as it represents separation from military life and a singular form of stress inherited in the transition to civilian life (Mobbs & Bonanno, Citation2018). Moreover, examining PMIEs and their consequences among IDF combatants poses a unique and interesting opportunity in light of the features of their two-track military assignments: (1) securing Israel's borders and participating in traditional armed conflict and (2) carrying out security and policing assignments, such as operating checkpoints, patrols, arrests, and ambush missions in the West Bank – an urban environment with close proximity to civilians at varied levels of conflict (Levi-Belz et al., Citation2022). Thus, Israeli combatants embody a highly relevant population for the current investigation, as their missions may expose them to ethical challenges, especially when non-combatants (e.g., civilian women and children) are involved (Gelkopf et al., Citation2016).

Operationally, we conducted a five-year longitudinal study with four measurement points: T1- information gathered from psychological tests and interview assessments that the veterans had undergone at the Military Induction Center (MIC), recorded approximately one year before army induction, thus, four years before discharge; T2- upon discharge from military service (three years after enlistment); T3- six months following discharge; and T4- 12 months following discharge. We posited the following hypotheses:

| 1. | Exposure to PMIEs will be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher probable depression, both longitudinally and at each measurement point. | ||||

| 2. | The impact of exposure to PMIEs on depressive symptoms will be moderated by time since discharge: Veterans exposed to PMIEs will show a decrease in their level of depressive symptoms at T3 (six months after discharge) and T4 (12 months after discharge) as compared to T2 (at discharge), above and beyond pre-enlistment personal characteristics, prior traumatic events, and combat exposure. | ||||

| 3. | Levels of PMIEs exposure at discharge (T2) will contribute to higher levels of depressive symptoms, and a greater prospect for self-reported depression diagnosis one year after discharge (T4), above and beyond pre-enlistment personal characteristics, prior traumatic events, and combat exposure. | ||||

Method

Participants

The sample included 374 active-duty combatants from four active IDF ground forces brigades (infantry, armored corps, special forces, and combat engineering). Israeli combatants in the IDF serve a mandatory 3-year military service between the ages of 18–21, with an additional year or more for officers. Most veterans will also remain as reserve combat troops and will be called up annually for 2–4 weeks to perform various military missions. Inclusion criteria called for participants to have served as active combatants, completed at least 30 months of their required combat military service, were to be discharged in the subsequent 3–4 weeks (for T2), and provided complete data at all three measurement points. Of all participants who gave their consent and completed the questionnaire forms at T2 (N = 959), 529 (55.1%) participated at T3, and 512 (53.3%) participated at T4. Overall, 374 participants (38.9%) completed all three measurements (T2–T4) and their data is analyzed in the study; for these participants, pre-enlistment data was collected (T1).

Three hundred fifty-four participants completed only one measurement: 345 participants provided data at T2, eight participants provided data at T3, and 1 participant provided data on T4; 231 participants completed only two measurements: 155 at T2 and T3, 64 at T2 and T4, and 12 participants at T3 and T4. Significant differences in religiosity were found between those who completed all measurements and those who did not, ꭓ2(10) = 35.59, p < .001: A higher number of participants who completed all measurements (56.9%) were secular compared with those not completing all measurements (41.7%). Moreover, the groups differed in their mean level of pre-enlistment Cognitive Index, F(2, 767) = 12.01, p < .001: Participants who completed all measurements endorsed higher levels of the Cognitive Index (M = 60.18, SD = 15.51) compared with those who completed two measurements (M = 55.47, SD = 15.92) and a single measurement (M = 53.86, SD = 16.73). No additional significant differences were found between the groups on other socio-demographic pre-enlistment variables and levels of PMIEs dimensions.

All participants in the study were in the same age cohort and enlisted in mandatory service in the IDF. All participants were males, and their mean age at T2 (at discharge) was 21.14 (SD = .80). On average, they had completed 12.01 (SD = .10) years of education. Most of the participants were Israeli-born (n = 325, 92.1%), unmarried (n = 348, 98.3%), and of secular religiosity (n = 170, 56.9%). Most participants served as combatants in infantry brigades (n = 259, 72.3%).

Procedure

The recruitment process for the second measurement (T2; approximately one month before discharge from the IDF) transpired during the first session of a 5-day civilian-life orientation workshop. This wave included an explanatory session regarding the study’s aims and outline. The explanations highlighted the anticipated three measurement waves and accessing participant data from the IDF recruitment bureau. We emphasized that consenting to participate would in no way affect their reserve military service or civilian life. At the end of this session, participants received a written explanation and an informed consent form for the study. After affirming their agreement to participate by signing the informed consent form, they completed the T2 questionnaires. Data at T2 were collected using hard-copy self-report questionnaires distributed by research assistants. For those completing the T2 measures, we collected pre-enlistment personal characteristics of cognitive index and performance prediction through the Military Induction Center’s (MIC) computerized records (T1).

The T3 and T4 waves of measurement took place six and 12 months after discharge, respectively. At T3 and T4, participants, who were now civilians/veterans, were approached by phone by research assistants. Those agreeing to continue their participation signed a new informed consent form, then were sent a link to the related online survey through an online data-gathering website. Recruitment for T3 and T4 included all participants who completed a full questionnaire at T2. Participants at T3 and T4 were sent a letter of thanks and were compensated with a gift card (approximately US$15). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the IDF Medical Corps Institutional Helsinki Committee, approval number 2139-2020.

Measures

Pre-enlistment: We collected pre-enlistment personality characteristics through the Military Induction Center’s (MIC) computerized records. Specifically, data were collected regarding participants’ cognitive index score and performance prediction, derived from a standard semi-structured interview conducted by trained psychology technicians and designed to predict soldier performance (Gal, Citation1986; see also Levi-Belz et al., Citation2018).

Cognitive Index (CI): An intelligence evaluation score, a highly valid measure of general intelligence, equivalent to a normally distributed I.Q. The CI comprises four subtests: Arithmetic and Similarities, which are similar to the equivalent subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence scales; Raven’s Progressive Matrices (a measure of nonverbal abstract reasoning and problem-solving abilities); and the Otis Test of Mental Ability, which measures the capacity to understand and carry out verbal instructions. CI scores range from 10 to 90, with a mean of 50 (Levi-Belz et al., Citation2018).

Performance Prediction Score (PPS): a composite score derived from the interview score and the empirically weighted scores on several indexes such as the cognitive index, combat suitability, years at school, and command of the Hebrew language. The scale score ranges from 42 to 56, with higher scores indicating a higher quality of soldier and combat capability (Gal, Citation1986).

Moral Injury Event Scale (MIES; Nash et al., Citation2013) is a self-report 9-item questionnaire tapping exposure to perceived transgressions during military service, comprising three subscales: (1) MIES-Self – four items assessing exposure to MI resulting from committing acts, failing to act, or making decisions perceived to be moral violations (e.g., “I acted in ways that violated my own moral code or values”); (2) MIES-Others – two items that assess exposure resulting from witnessing or learning about others’ actions perceived to be moral violations (e.g., “I am troubled by having witnessed others’ immoral acts”); and (3) MIES-Betrayal – three items that assess exposure to MI resulting from perceiving deception or betrayal by others (e.g., “I feel betrayed by fellow service members whom I once trusted”). Items are presented on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). For the present study, we used the MIES total endorsements as well as the scores of three dimensions at the three measurement points of T2–T4 with regard to military service. For the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for MIES-Self (T2) = .88, MIES-Other (T2) = .87, and MIES-Betrayal (T2) = .78; MIES-Self (T3) = .89, MIES-Other (T3) = .84, and MIES-Betrayal (T3) = .76; MIES-Self (T4) = .90, MIES-Other (T4) = .86, and MIES-Betrayal (T4) = .73.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., Citation200Citation9). The PHQ-8 is a widely used instrument for self-reporting the frequency of depressive symptoms (e.g., anhedonia, depressed mood, disturbances in sleep and appetite) over the previous two weeks, presented on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score comprised the sum of the eight items. In this study, our analysis used the total score of the PHQ-8 as a continuous variable and as an indication of a self-reported depressive diagnosis, using the validated cut-off value /of ≥ 10 (Manea et al., Citation2012). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the PHQ-8 for the current sample were α = .87 (T2), α = .87 (T3), and α = .86 (T4).

Combat Experiences Scale (CES; Hoge et al., Citation2004). Combat experiences were examined with 18 items listing a range of conventional modern combat, such as being ambushed, being shot or directing fire at the enemy, and handling or uncovering dead bodies or body parts. Respondents were asked to indicate which events they had experienced during a deployment, resulting in a total number of combat experiences ranging from 0 to 18. Combat experiences were modified from previous scales (Castro et al., Citation2012) and have been used in the same way as the original scale (Hoge et al., Citation2004). The psychometric properties of the more advanced CES, incorporating the original CES items, have been well-demonstrated (Guyker et al., Citation2013). The CES was administered only at T2. Cronbach's α on CES items for the present sample was .72.

Socio-demographic Information: The following demographic characteristics were obtained at T2: age, gender, family status, religiosity, educational level, and military service characteristics. Furthermore, for statistical control, we assessed the Life Events Checklist (LEC-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013). Participants’ potentially traumatic and negative life events were assessed with the LEC-5 self-report questionnaire composed of 17 potential traumatic events (PTEs) over the participant's life before his enlistment that could lead to psychological distress.

Pre-enlistment (one year prior to service; T1): Data were collected regarding participants’ Cognitive Index score and performance prediction of combatants, derived from a standard IDF semi-structured interview conducted by trained IDF psychology technicians, and designed to predict soldier performance (Gal, Citation1986; see also Levi-Belz et al., Citation2018).

Statistical analysis

First, we calculated descriptive statistics, rates of probable depressive symptoms and prevalence of PMIEs. For the first hypothesis, we calculated a series of Pearson correlations between the sum scores of PMIEs dimensions and depressive symptoms (T2-T4), and by chi2 analyses for probable depression diagnoses. For the second hypothesis, we examined reported depressive symptoms (at T2-T4) of those who were exposed to at least one PMIE during their military service (T1), compared with veterans who were not exposed to PMIEs, using an ANCOVA with repeated measures.

To address the third hypothesis regarding the unique contribution of PMIEs dimensions to depressive symptoms and probable depression at T4, a four-step hierarchical regression analysis and four-step logistic regression analysis were conducted, respectively. On both regressions, at Step 1, we entered measures of depressive symptoms at T1 and T2 for statistical control. At Step 2, we entered negative life events before enlistment, pre-enlistment personal characteristics derived from the MIC computerized records (T1). At Step 3, we entered combat exposure experiences, while at Step 4, we entered exposure to PMIE dimensions of Self, -Other and -Betrayal at T2. The missing data were handled using the listwise method. All analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS software (Version 28; 2022).

Results

Prevalence of PMIEs and depressive symptoms over the first year following discharge from military service

This section reviews the descriptive statistics, the rates of self-reported PMIEs, and depressive symptoms at T2, T3 and T4. Regarding the exposure to PMIEs, 48.7% (n = 181) of the participants endorsed at least one MIES item at T2, 42.4% (n = 154) endorsed at least one MIES item at T3, and 30.7% (n = 114) endorsed at least one MIES item at T4 at the slightly agree or higher level. Furthermore, we examined the prevalence of participants who met the criteria of probable current depression using self-report diagnosis and validated cut-offs. The prevalence of current depression at T2 was 12.0% (n = 45); at T3, it was 4.8% (n = 18); and at T4, it was 6.4% (n = 24).

Associations between PMIEs, depressive symptoms and probable depression over the first year following discharge from military service

To test the first hypothesis in which exposure to PMIEs will be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher probable depression, a series of Pearson correlation analyses were conducted. As can be seen from , all PMIE dimensions were positively related to higher levels of depressive symptoms at each measurement wave and longitudinally (rrange = .18–.46), with two exceptions: PMIE self and PMIE other at T2 were not significantly correlated with depression at T3.

Table 1. Pearson correlation coefficients between the main study variables.

Regarding probable depression, we examined the differences in the rates of probable depression with regard to PMIE endorsement at T2. Generally, we found that the rates for probable depression were significantly higher among combatants with PMIE endorsement at all the measurement points: At T2- 16.7% (n = 33) of the combatants who endorsed PMIE had probable depression as compared to 5.5% (n = 9) combatants who did not endorse PMIE and had probable depression (Chi2 = 11.58, p < .0001). At T3- 10.1% (n = 20) of the combatants who endorsed PMIE had probable depression as compared to 2.4% (n = 4) of combatants who did not endorse PMIE and had probable depression (Chi2 = 8.59, p < .001). At T4- 8.1% (n = 16) of the combatants who endorsed PMIE had probable depression as compared to 0.6% (n = 1) of combatants who did not endorse PMIE and had probable depression (Chi2 = 8.59, p < .001).

To test the second hypothesis regarding the moderation of time in the impact of exposure to PMIEs on depressive symptoms, we conducted a repeated-measures ANCOVA, with depressive symptoms (T2-T4) as the dependent variable and endorsement of at least one PMIE (T2) as the independent variable. We controlled statistically for the sum of pre-enlistment negative life events, the cognitive index score, and performance prediction. Results revealed a significant interaction effect between time and PMIE endorsement, F(2,328) = 5.65, p < .001, ὴ² = .03. As seen in , for those who endorsed at least one PMIE at T2, the severity of depressive symptoms decreased significantly between T2 and T3, and between T2 and T4, but not between T3 and T4, F(2,328) = 8.26, p < .001, ὴ² = .05. However, for those endorsing no PMIEs at T2, the severity of depressive symptoms decreased only between T3 and T4, F(2,328) = 3.02, p < .06, ὴ² = .02.

Pre-enlistment characteristics, combat exposure, and PMIEs as contributors to depressive symptoms at T4

In line with the third hypothesis of this study, we examined the contribution of pre-enlistment characteristics, combat exposure, and PMIEs to the sum of depressive symptoms (severity) and probable current depression (yes/no) at T4. Firstly, we assessed the means, standard deviations, ranges, and intercorrelations for all main variables before the main analyses. shows that pre-enlistment negative life events were associated with higher levels of combat exposure, PMIEs, and depressive symptoms at T2-T4. The cognitive index score was positively related to exposure to PMIE-Other (T4), and performance prediction was negatively associated with PMIE-Self (T2, T4). Moreover, combat exposure was positively related to higher levels of exposure to all three PMIE dimensions and depressive symptoms (T2-T4).

To determine if the PMIE-dimensions can predict the sum of depressive symptom severity at T4, we performed a four-step hierarchical regression. The entire set of variables in the final model explained 39.1% of the variance of depressive symptoms one year after discharge (T4), F(9,333) = 24.72, p < .001. As seen in , we found that depressive symptoms at T2 and T3 contributed positively to depressive symptoms at T4. Importantly, PMIE-Betrayal (T2) was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (T4), above and beyond depressive symptoms at T2 and T3, pre-enlistment characteristics, and combat exposure.

Table 2. Summary of hierarchical regression coefficients of depressive symptoms (T4) by pre-enlistment characteristics combat exposure and PMIES.

We also examined the contribution of PMIEs to current probable depression (T4) through the independent variables. As seen in , the four-step logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(8) = 46.60, p < .001. The model explained 39.3% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in current depression (T4) and correctly classified 96.4% of cases. Participants exceeding the cut-off score for depression at T2 were 11.03 times more likely to exhibit depression (T4) than participants who did not exceed the cut-off score. Importantly, PMIE-Betrayal (T2) was associated with an increased likelihood of exhibiting current depression at T4 (Exp(B) = 1.24).

Table 3. Logistic regressions predicting probable depression (T4) by pre-enlistment characteristics combat exposure, and PMIES.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to shed light on the contribution of PMIE exposure to depressive symptoms and self-reported depressive diagnosis in a 5-year longitudinal study of Israeli combatants. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine the role of PMIEs in depression during the first year after discharge among combatants.

Our results confirm the study hypotheses. Our findings indicate a high frequency of exposure to PMIEs among our combatant sample: Almost half (48.7%) of the participants reported PMIE exposure at their discharge from military service, a significantly higher proportion than in other armies (e.g., Maguen et al., Citation2021; Wisco et al., Citation2017), and among Israeli veterans up to ten years from discharge (Zerach & Levi-Belz, Citation2018). Interestingly, the veterans’ perception of their exposure to PMIEs declined over time, from discharge (48.7%) to one year afterward (30.7% at T4). These findings underscore the importance of time since release as a critical factor in examining the prevalence of PMIEs, as reporting exposure to PMIEs is a subjective phenomenon and may change in different time periods. Moreover, our data reveal that PMIEs are perceived at discharge as having been more frequent during military service than years following discharge. This distinction also has methodological implications, as many studies examining PMIE prevalence need to acknowledge that such prevalence may change over time since discharge.

More central to the present study and in line with Hypotheses 1 and 2, we found that greater exposure to PMIEs during military service is associated with greater severity of depressive symptoms and probable depression diagnosis at all measurement points among combat veterans, and that this effect was moderated by time since release: The effect of exposure to PMIEs on depression was highest at discharge (T2) and declined at T3 and T4. Previous studies have shown that PMIEs may be associated with significant deleterious mental effects among combatants and veterans, such as depression (e.g., Griffin et al., Citation2019). However, the current study highlighted the continuous effect of PMIEs on depression throughout the first year after discharge. As previous exposure to PMIEs continues to facilitate greater depressive symptom severity, we suggest that future studies examine the deleterious effects of PMIE exposure on different psychopathologies and functional domains over time.

In line with our Hypothesis 3, we found a significant positive effect of PMIE-Betrayal at discharge (T1) on the severity of depressive symptoms and self-reported depression diagnosis one year after discharge (T4), above and beyond the natural trajectory of depression as well as above pre-enlistment characteristics of negative life events, cognitive Index, and performance prediction. Overall, these findings confirmed Litz et al.’s (Citation2009) conceptual model and are congruent with other studies finding PMIE-Betrayal as a risk factor for psychiatric symptoms in military settings (e.g., Jordan et al., Citation2017; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2023; Zerach & Levi-Belz, Citation2018) and other settings (e.g., Zerach & Levi-Belz, Citation2022). Taken together, the current findings suggest that exposure to PMIEs in general, specially PMIEs of betrayal, have a profoundly negative influence on veterans’ mental health, predicting depression even beyond the effects of combat exposure, one of the significant predictors of psychopathology among veterans (e.g., Able & Benedek, Citation2019).

PMIE-Betrayal comprises a high-magnitude moral injury related to a faulty action performed by a trusted authority figure (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016). The betrayal experience may be related to commanders who betrayed veterans’ moral and ethical expectations concerning their responsibility for critical combat situations. Generally, soldiers expect their commanders to be supportive, such as providing adequate equipment to protect them in combat and social support in difficult situations. Notably, some studies have suggested that betrayal experiences may place the betrayed individuals at risk for perpetrating other transgressive acts and increase their vulnerability to adverse consequences (Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020). Twenty years ago, Shay (Citation1994) speculated that betrayal by commanding authorities corrodes the military units’ cohesion and effectiveness as well as combat personnel's safety and security. The current findings confirmed this notion, indicating that the betrayal experience may weaken the resilience of the combatants upon their discharge from the army, and this impact continues its impact on the veterans in the year following their discharge.

The current study should be interpreted in light of several methodological drawbacks. First, although T1 measurements relied on semi-structured interviews, at T2-T4, we used self-report measures, which may suffer from various biases. This drawback is particularly evident regarding the depression disorder diagnosis, assessed by a self-report scale in the absence of objective or professional assessment, thus making it susceptible to estimation bias. Second, pre-enlistment negative life events were measured only at T2, thus introducing a well-known range of biases caused by factors such as mood-dependent recall, forgetting, cathartic effect, and social desirability. Third, as this study comprises an Israeli combatant sample, cultural and military context differences, such as types of exposure and the factor of mandatory military service, should be acknowledged.

The study’s findings have several clinical implications. The results highlight the clinical relevance of PMIE experiences as a source of increased potential for depression among recently discharged veterans. Considering the high PMIE rates in our study, it is clear that routine screening for PMIEs should be conducted among military personnel at discharge, as this time frame entails the critical tasks of processing their experiences in their military service as well as dealing with the stress of transitioning to civilian life (Mobbs & Bonanno, Citation2018). PMIE experiences can exacerbate feelings of shame, guilt, and self-disgust that, separately and together, could be detrimental to the discharged soldier (Currier et al., Citation2014) and lead to greater severity of depressive symptoms.

Following the screening of discharged soldiers, specific interventions highlighting various aspects of PMIE experiences should be available to them, with a direct focus on depressive symptoms that have been found to accompany experiences of moral injury. For example, psycho-education sessions addressing the negative emotions commonly arising after transgressive acts may help veterans understand their emotional state and enhance their coping. The cognitive reappraisal technique, an emotion regulation strategy in CBT (Ray et al., Citation2010), can aid veterans in altering the trajectory of their emotional response and their perspectives of morally injurious events by reframing the meaning of the MI. Moreover, using specific interventions, like adaptive disclosure, can be recommended, as it is designed to help veterans create a capacity to cope and psychologically process the emotional difficulties of PMIE experiences (Litz et al., Citation2017). These suggestions are consistent with the “reparation and forgiveness” step of Litz et al.'s (Citation2009) working clinical care model. These processes of reparation and forgiveness at discharge may help alter the veterans’ subjective perceptions of PMIEs and, thus, change their course of coping with their military service experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Able, M. L., & Benedek, D. M. (2019). Severity and symptom trajectory in combat-related PTSD: A review of the literature. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(7), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1042-z

- Arditte Hall, K. A., Davison, E. H., Galovski, T. E., Vasterling, J. J., & Pineles, S. L. (2019). Associations between trauma-related rumination and symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in treatment-seeking female veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(2), 260–268.

- Bartone, P. T., & Homish, G. G. (2020). Influence of hardiness, avoidance coping, and combat exposure on depression in returning war veterans: A moderated-mediation study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.127

- Bonde, J. P., Utzon-Frank, N., Bertelsen, M., Borritz, M., Eller, N. H., Nordentoft, M., Olesen, K., Rod, N. H., & Rugulies, R. (2016). Risk of depressive disorder following disasters and military deployment: Systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(4), 330–336. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.157859

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. O., Anestis, M. D., Anestis, J. C., Green, B. A., Etienne, N., Morrow, C. E., & Ray-Sannerud, B. (2016). Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment, 23(5), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115590855

- Castro, C. A., Adler, A. B., Mcgurk, D., & Bliese, P. D. (2012). Mental health training with soldiers four months after returning from Iraq: Randomization by platoon. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(4), 376–383.

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Jones, H. W., & Sheu, S. (2014). Involvement in abusive violence among Vietnam veterans: Direct and indirect associations with substance use problems and suicidality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032973

- Farnsworth, J. K., Drescher, K. D., Evans, W., & Walser, R. D. (2017). A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(4), 391–397. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.07.003

- Frankfurt, S., & Frazier, P. (2016). A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychology, 28(5), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000132

- Gal, R. (1986). A portrait of the Israeli soldier (No. 52). Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Gelkopf, M., Berger, R., & Roe, D. (2016). Soldiers perpetrating or witnessing acts of humiliation: A community-based random sample study design. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 22(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000154

- Ginzburg, K., Ein-Dor, T., & Solomon, Z. (2010). Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression: A 20-year longitudinal study of war veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 123(1–3), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.006

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., Villierme, C., Walsh, J., & Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22362

- Guyker, W. M., Donnelly, K., Donnelly, J. P., Dunnam, M., Warner, G. C., Kittleson, J., Bradshaw, C., Alt, M., & Meier, S. T. (2013). Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the combat experiences scale. Military Medicine, 178(4), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00223

- Hassija, C. M., Jakupcak, M., Maguen, S., & Shipherd, J. C. (2012). The influence of combat and interpersonal trauma on PTSD, depression, and alcohol misuse in US Gulf War and OEF/OIF women veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(2), 216–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21686

- Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., Mcgurk, D., Cotting, D. I., Koffman, R. L., (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040603

- Jordan, A. H., Eisen, E., Bolton, E., Nash, W. P., & Litz, B. T. (2017). Distinguishing war-related PTSD resulting from perpetration-and betrayal-based morally injurious events. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(6), 627–634. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000249

- Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026

- Levi-Belz, Y., Ben Yehuda, A., & Zerach, G. (2023). Suicide risk among combatants: The longitudinal contributions of pre-enlistment characteristics, pre-deployment personality factors and moral injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 324, 624–631. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.160

- Levi-Belz, Y., Dichter, N., & Zerach, G. (2022). Moral injury and suicide ideation among Israeli combat veterans: The contribution of self-forgiveness and perceived social support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), NP1031–NP1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520920865

- Levi-Belz, Y., Greene, T., & Zerach, G. (2020). Associations between moral injury, PTSD clusters, and depression among Israeli veterans: A network approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1736411. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1736411

- Levi-Belz, Y., Krispin, O., Galilee, G., Bodner, E., & Apter, A. (2018). Where are they now? Longitudinal follow-up and prognosis of adolescent suicide attempters. Crisis, 39(2), 119–126.

- Litz, B. T., Lebowitz, L., Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2017). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford Publications.

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Maguen, S., Nichter, B., Norman, S. B., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2021). Moral injury and substance use disorders among US combat veterans: Results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001628

- Manea, L., Gilbody, S., & McMillan, D. (2012). Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(3), E191-E196. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110829

- McCabe, C. T., Watrous, J. R., & Galarneau, M. R. (2020). Trauma exposure, mental health, and quality of life among injured service members: Moderating effects of perceived support from friends and family. Military Psychology, 32(2), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2019.1691406

- McEwen, C., Alisic, E., & Jobson, L. (2021). Moral injury and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Traumatology, 27(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000287

- Mobbs, M. C., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Beyond war and PTSD: The crucial role of transition stress in the lives of military veterans. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.007

- Nash, W. P., Carper, T. L. M., Mills, M. A., Au, T., Goldsmith, A., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Military Medicine, 178(6), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Ray, R. D., McRae, K., Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Cognitive reappraisal of negative affect: Converging evidence from EMG and self-report. Emotion, 10(4), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019015

- Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Atheneum Publishers/Macmillan Publishing Co.

- Snir, A., Levi-Belz, Y., & Solomon, Z. (2017). Is the war really over? A 20-year longitudinal study on trajectories of suicidal ideation and posttraumatic stress symptoms following combat. Psychiatry Research, 247, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.065

- Walker, L. E., Watrous, J., Poltavskiy, E., Howard, J. T., Janak, J. C., Pettey, W. B., Zarzabal, L. A., Sim, A., Gundlapalli, A., & Stewart, I. J. (2021). Longitudinal mental health outcomes of combat-injured service members. Brain and Behavior, 11(5), e02088. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2088

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov

- Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(6), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55

- Wisco, B. E., Marx, B. P., May, C. L., Martini, B., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depression and Anxiety, 34(4), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22614

- Zerach, G., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2018). Moral injury process and its psychological consequences among Israeli combat veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(9), 1526–1544. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22598