ABSTRACT

This review of 16 prevention-related publications in Eating Disorders during 2022 is framed by three models: (1) Mental Health Intervention Spectrum: health promotion → types of prevention → case identification/referral → treatment; (2) the prevention cycle: rationale and theory, shaped by critical reviews → clarifying risk and protective factors → program innovation and feasibility studies → efficacy and effectiveness research → program dissemination; and (3) definitions of and links between disordered eating (DE) and eating disorders (EDs). Seven articles fell into the category of prevention rationale (including screening studies) and relevant reviews, while nine articles addressed correlates of/risk factors (RFs) for various aspects of DE and EDs. One implication of the 16 articles reviewed is that RF research toward construction of selective and indicated prevention programs for an expanding array of diverse at-risk groups needs to address, from a nuanced, intersectional framework, a broad range of factors beyond negative body image and internalization of beauty ideals. Another implication is that, to expand and improve current and forthcoming prevention programs, and to shape effective advocacy for prevention-oriented social policy, the field in general and Eating Disorders in particular need more scholarship in the form of critical reviews and meta-analyses; protective factor research; prevention program development and multi-stage evaluation; and case studies of multi-step activism at the local, state (province, region), and national levels.

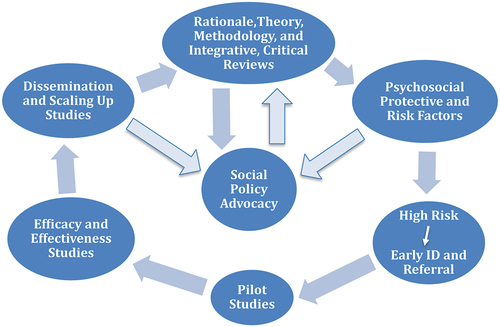

This article reviews 16 prevention-related publications in Eating Disorders during 2023. Using phases of the prevention cycle shown in , these articles are categorized in , and in the References section they are preceded by an *. For each phase, also recommends two or three reviews or research articles published in other journals in 2023. Other notable prevention-related reviews that do not fit readily into the categories used in address prevention of anorexia nervosa (AN), in particular (Korsak, Citation2023); early intervention in, as well as prevention of, eating disorders (EDs; Koreshe et al., Citation2023); economic evidence for prevention and treatment of EDs (Faller et al., Citation2023); and psychosocial interventions designed to improve body image and reduce DE in adult men (Hendricks et al., Citation2023).

Figure 1. The cycle of prevention theory, research, and advocacy. Adapted from Levine and Smolak (Citation2021).

Table 1. Phases of prevention cycle and the 16 prevention-related articles in the 2023 issues of Eating Disorders (Volume 29).

One form of prevention-related research that is hard to classify is the screening of groups to assess the level of risk for eating disorders (EDs). If that level is very high for an individual, a structured interview may be administered to determine whether they already have an ED and need referral for treatment. In prevention science and/or online screening (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., Citation2019), individuals or subgroups whose level of risk is moderate to high—and thus can be said to be engaging in disordered eating (DE; see )—may be referred for selective or indicated prevention. A high level of risk for an entire population or a large, representative segment of it may activate a prevention campaign from public health officials. With regard to screening for DE and EDs, notable this past year are reviews focusing on high-school students (Ghazzawi et al., Citation2023) and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (Martin et al., Citation2023).

Table 2. Proposal for a prototypical definition of disordered eating.

Key conceptsFootnote1

Prevention

In the field of mental health, prevention is defined in terms of “three interrelated goals: (a) evading or forestalling the development of psychological disorder or unhealthy behavior; (b) protecting current states of health and effective functioning; and (c) promoting greater well-being so as to strengthen resilience in the event of predictable or unforeseen stressors” (Levine & Smolak, Citation2021, pp. 9–10). Prevention is also a general designation for planned and monitored changes in sociocultural, interpersonal, and personal factors that are designed to forestall entirely or substantially delay onset of a disorder. Interventions that reduce risk factors and/or increase protective factors, but have not yet been shown to prevent EDs, should be called risk factor reduction, protective factor activation, or body image improvement programs (Becker, Citation2016). The ultimate goal of these programs is prevention, but they do not (yet) merit the label “prevention program.”

Disordered eating

It is important to distinguish between EDs, defined by diagnostic criteria, and disordered eating (DE). Research within the sociocultural, public health, and feminist paradigms strongly supports the proposition that the EDs are, at least in part, the extreme ends of a set of interlocking DE characteristics that are normally distributed in the populations of many countries. While acknowledging that this continuity model is a complicated, even controversial proposition, Levine and colleagues (Alhaj et al., Citation2022; Levine & Smolak, Citation2021; Smolak & Levine, Citation2015) have developed a preliminary DSM-5-like prototypical (or protean) approach to defining DE. As some form of DE is a primary or secondary criterion variable for 11 (~68.5%) of the 16 prevention-related articles published in Eating Disorders in 2023, that definition is shown in .

Risk and protective factors

Over the past 40 years the ambiguities inherent in cross-sectional correlations and the difficulties in demonstrating “causality” in the lives of humans have led to an emphasis on the constructs of “risk factor,” “protective factor,” and people who are “at risk.” Granted, in cross-sectional and longitudinal research, lack of correlation does demonstrate lack of a direct causal connection. Moreover, the status of cross-sectional, correlational evidence for demonstrating a risk or protective factor is strengthened when the pattern of results from a retrospective case-controlled design, a path analysis, or some type of mediation analysis is predicted a priori by a theory that already rests on a strong research foundation.

Nevertheless, prevention focuses in large part on variable risk or protective factors, operating in and across multiple ecological levels, that meet three criteria (Jacobi et al., Citation2004; Kraemer et al., Citation1997; Smolak, Citation2012). First, the factor precedes onset of the disorder (in determining risk) or no onset (in determining what is protective). Second, longitudinal or controlled retrospective research shows the putative factor to be a statistically significant predictor of that dichotomous outcome. Third, the factor can be modified. If a set of studies show that a preventive intervention reduces that variable risk factor – or increases that variable protective factor – and thereby significantly reduces the probability of disorder onset, then that variable is a causal risk factor or a causal protective factor. One more important consideration is whether the factor is specific to DE and/or EDs, versus non-specific because it meets the three criteria in relation to multiple psychological disorders.

Frameworks

The Mental Health Intervention Spectrum (Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults [National Research Council & Institute of Medicine of the National Academies], Citation2009) describes policies and programs whose goals vary from general health and resilience promotion → universal prevention → selective prevention → indicated (targeted) prevention → assessment (screening) for case identification → intervention → aftercare. presents the cyclical phases in the development of preventive interventions: Prevention rationale (including screening for risk and/or disorder), theory, and methodology—sometimes supported and extended by integrative/critical reviews and meta-analyses → clarification of protective and risk factors—including very high risk, shading into warning signs—that determine intervention objectives → program design and feasibility (pilot) research → efficacy and effectiveness studies → program dissemination, including evaluation of cost-effectiveness, plus clarification of internal and external obstacles to scaling up of programs and/or to program participation. In addition to programs for individuals, small groups, and populations of varying size, prevention includes translation of epidemiological findings, risk/protective factor research, and developments in other fields (e.g., economics and communications) into the multiple, recursive steps involved in advocating for macro-level changes in laws, public policies, industry practices, and cultural norms (Austin, Citation2016).

Rationale, theory, methodology, and critical reviews

In 2023 seven Eating Disorders articles fell into this broad category. Three added to the rationale for prevention of the onset of binge eating, a feature of DE and EDs, not only in young women but also in women across the lifespan. Another article was a meta-analysis conducted to guide development of prevention programs. The remaining three articles addressed topics pertaining to screening for DE and/or risk for EDs. Eating Disorders did not publish any integrative critical reviews or commentaries focusing primarily on theory or methodology.

Rationale

Two studies addressed the relationship between EDs and both suicidal ideation and suicide. Amiri and Khan (Citation2023) conducted a meta-analysis of 52 studies, published in English through April 2022, that examined the links between EDs and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and/or suicide mortality. The vast majority of the participants were female—only four of the studies appeared to have more than 15% male participants, and in 22 of the studies all participants were female—and all the studies were conducted in developed countries.

The data demonstrated that, although there was great variation in prevalence across studies within each category, there is no doubt that NSSI (weighted mean prevalence = 40%), suicidal ideation (51%), and suicidal attempts (22%) are a significant clinical feature of many of the EDs. As expected on the basis of previous research linking binge eating and purging to impulsivity and emotional disregulation, and although many people think of anorexia nervosa (AN) as being “more severe and serious” than bulimia nervosa (BN), features of self-harm, despair, perceived burdensomeness to self and others, and hopelessness were more prominent in BN than AN: NSSI (44% vs. 29%), suicidal ideation (60% vs. 50%), and suicidal attempts (25% vs. 17%).

The results of Amiri and Khan’s (Citation2023) meta-analysis reinforce one key component of the rationale for prevention. EDs are serious biopsychosocial disorders that reflect, maintain, and cause substantial harm to and misery for the individual. The study by Thiel et al. (Citation2023) indicates that we have a long way to go to understand the relationship between DE at least and suicidal ideation in undergraduate students because a 10-week longitudinal study (3 assessments) provided no support for Joiner’s well-established interpersonal theory of suicidal ideation. In this sample of 351 U.S. undergraduates neither initial (T1) EDE-Q global scores nor subscale scores predicted changes (T1-T2) in perceived burdensomeness, a sense of thwarted belonging, or hopelessness These change variables in turn did not predict suicidal ideation at T3.

Prevention as a field developed from concerns about the prevalence, incidence, and transmission of (including risk factors for) disease in populations and, by extension, particular groups within larger populations. Take a moment and without much thought activate a description and/or image of a person who engages in binge eating (BE) as an aspect of BN, binge eating disorder (BED), or DE. If you are like me, that exemplar is, at the very least, well under age 55.

Kilpela et al. (Citation2023) conducted telephone interviews with 71 women who responded to online and public recruitment seeking “women aged 60+ who experienced BE in the past month (‘In the past month, have you eaten an unusually large amount of food in one sitting AND felt that your eating was out of control at that time’)” (p. 481). Nearly 58% met the DSM-5 frequency and duration criteria for objective binge eating (OBE), while another 20% met the subclinical OBE criteria included in the Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders category. It is important for prevention researchers and advocates to note that two-thirds of these women with OBE reported onset after age 40, including nearly half who developed OBEs after age 56. Further, such binge eating was accompanied by significant self-blame, guilt, shame, anxiety, and other forms of misery. Kilpela et al.’s (Citation2023) findings strongly suggest the need for epidemiological studies that will clarify the extent of the need for binge eating prevention programs for what has long been overlooked as a developmentally vulnerable subgroup: women over 40 in general, and women in late middle age in particular.

Screening for DE and/or risk for eating disorders

In the Mental Health Intervention Spectrum indicated prevention for DE is closely related to early identification of EDs and referral for treatment, steps once called “tertiary prevention” because the goal was keeping an inchoate disorder from becoming more severe and possibly chronic (Caplan, Citation1964). For recent reviews of theory and research pertaining to early identification of EDs, see Mills et al. (Citation2023) and Radunz et al. (Citation2023).

Doney et al. (Citation2023) investigated the relative prevalence of “ED symptomatology,” that is, DE (see ), in U.S. male and female undergraduates who belong to college fraternities and sororities. These researchers analyzed the responses of ~43,500 cisgender undergraduates to the 5-item SCOFF screening instrument for EDs that was part of the pre-pandemic (2018–2019) Healthy Minds Study survey of 62,000 students attending 79 universities and colleges. Contrary to some previous research and to many people’s stereotypical expectations for sororities, neither affiliation with “Greek life” nor living in a sorority or fraternity house had a significant association with DE (ED risk) for either females or males. These null findings are consistent with those of a fairly large scale (N = ~5,800) study by Averett et al. (Citation2017) in suggesting that campus prevention work should not “target” the “Greeks” as a high-risk group of people. Doney et al. (Citation2023) point out that one potentially fruitful direction for further epidemiological research with U.S. undergraduates is a more granular investigation of whether the constructed subcultures of some fraternities and sororities are more objectifying, materialistic, and competitive, resulting in a culture of risk for EDs analogous to those in certain sports and professions.

Responses to direct questions from healthcare professionals, obtained in the course of office or hospital visits, constitute another type of self-report data that is important for identifying severe DE or clinically significant EDs and initiating the treatment referral process. As Forney et al. (Citation2023) note, previous research indicates that only a third of people who have EDs received inquiries about their eating from healthcare professionals. Forney et al. argue that, regardless of whether the person conducting the screening is using a survey or a semi-structured interview, it is likely that complaints about postprandial elevations in feeling full or bloated are strong indicators of the need to pursue further inquiry about DE and EDs.

Forney et al.’s survey of 281 U.S. undergraduates (~70% female, ~84% White) confirmed a significant association between these warning signs and purging, as well as the presence of an ED, particularly when the student had higher levels of body dissatisfaction. These results support the hypothesis that identification and timely treatment of EDs for undergraduates will be improved by assessment of body dissatisfaction and other features of DE in those who seek medical attention for gastrointestinal complaints related to eating. Forney et al. observe that another interesting research question is whether undergraduates with negative body image are predisposed to interpret feelings of fullness and being bloated as proprioceptive signals that they are becoming fat(ter). If this is the case, longitudinal research should explore the implications for a maladaptive cycle in which eating → feeling full/bloated → feeling “fat” and “uncomfortable” → (more) restrictive eating → increased probability of feeling full/bloated after eating.

Self-report data are not the only useful type of screening information. Another source of information is people who care about the individual(s) in question, spend a lot of time with them, and are motivated to pay attention to attitudes, including behaviors. Principal among people in this position are parents and other caregivers. Based on the “lack of reliable and valid parent-report measures assessing eating disorder (ED) pathology in children and adolescents” (p. 651), Webster et al. (Citation2023) adapted the short form of the well-known Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-QS) to construct, and evaluate the psychometric properties of, a 12-item Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire-Short Parent Version (EDE-QS-P).

In a sample of 296 U.S. parents seeking ED treatment for their child or adolescent (ages 6 through 18; 84% female, 79% White) an 11-item version of the EDE-QS-P had an acceptable single-factor solution, was internally consistent, and showed solid convergent validity in terms of hypothesized correlations with offspring’s scores on the EDE-Q (r = .69), as well as measures of generalized anxiety (r = .37) and general poor health (r = .46). Moreover, parent scores on the EDE-QS-P were able to distinguish children with EDs characterized by body image disturbances from children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), an ED that does not revolve around weight/shape concerns. These findings strongly support further investigations of the value of the 11-item EDE-QS-P for identifying ED pathology in children and adolescents and, perhaps, tracking natural and treatment-induced changes over time.

Integrative review

One notable development in prevention research in the past 10 years is the emergence of programs that emphasize or incorporate protective factors such as self-compassion or appreciation of body functionality (Levine & Smolak, Citation2016). Babbott et al. (Citation2023) conducted a systematic and meta-analytic review of interventions promoting intuitive eating (IE). This is a potentially protective factor because IE is designed to promote positive relationships with food, hunger, and satiety, framed by self-compassion in emotion regulation, by greater appreciation of the body’s wisdom in knowing what it does and does not need, and by rejection of the dieting mentality. Searches of four databases, plus several sources of unpublished research, yielded nine studies that delivered an IE intervention and used the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES), of which six (encompassing seven effects) met the criteria for inclusion in a meta-analysis. On average, the study quality was only fair, and over 80% of the participants were female and White.

Babbott et al.’s meta-analysis (Citation2023) found that all the interventions evaluated produced pre- to post-test improvement in IE, with a very large pooled effect size (1.50 [CI = 1.15, 1.85]). There were also positive changes on a variety of other outcomes such as improved body image, lower levels of DE, and better quality of life. In addition, there were no indications of unexpected negative outcomes, at least on a group level. This pattern supports further program development and evaluation research in testing the proposition that IE interventions do indeed cultivate healthier attitudes about food, eating, and the body, which promote healthier eating and self-care, thereby reducing the risk of DE and EDs.

Correlates, risk factors, and “triggers” informing prevention

In 2023, Eating Disorders published nine articles pertaining to correlates, risk factors, and “triggers.” In four the criterion variable (i.e., the variable being predicted) was one or more of the EDs, while in five studies the criterion was DE or a feature of DE, including one study in which the criterion was “muscularity-oriented disordered eating.”

EDs

Developmental processes

Three articles published in Eating Disorders in 2023 are potentially relevant to prevention because they address, in quite different ways, variables that are already established as risk factors or that may turn out to be risk factors or moderators. To identify “triggers” for the development of AN and atypical AN, Lin et al. (Citation2023) reviewed the initial admission records of 150 youth (ages 9 through 18, M = 14; 86% female, 80% Non-Hispanic White) who were treated for these two EDs at an Eastern U.S. hospital between early 2015 and early 2020. As expected, the triggers reported by 93% of the patients and/or parents included environmental stressors (reported by 30%) such as divorce or having to change schools, sociocultural pressures to adhere to the thin/fit ideal (29%), and personal decision to internalize the thin/fit ideal (28.5%). Desire to live in a healthier fashion (21%), weight-related teasing (19%), and receiving health education (14%) were also recorded as triggers for a minority of youth, and the latter two were significantly more likely to be reported by or for those who were younger. As expected, youth who were overweight or obese, according to developmental standards for body mass index (BMI), were more likely to report weight-related teasing and/or positive reinforcement for weight loss as triggers, but it was surprising that males were significantly more likely than females to report internalization of the thin/fit ideal. These data highlight the similarities in self-reported triggers, several of which are consistent with risk factors for EDs in general (Smolak, Citation2012), for children and adolescents diagnosed with AN and those with atypical AN. The findings also partially contradict the statement that I have frequently heard from parents and caregivers who advocate a disease model of AN, namely that “severe AN is an illness of the brain and has nothing to do with beauty ideals or other sociocultural factors.”

Understanding and differentiating clinical characteristics

Currently, it is unclear from the risk factor literature, including prevention studies, that what is necessary to prevent, for example, binge eating or binge-eating spectrum disorders, is the same as the requirements for preventing dietary restraint or restricting disorders, such as that subtype of AN. Martin-Wagar and Weigold (Citation2023) applied hierarchical regression analysis to cross-sectional data from a sample of 98 U.S. women (Mage = ~29.5 yrs; ~92% White) across the weight spectrum who had EDs. Controlling for both BMI and previous weight bias experiences, three features of internalized stigma that are related to weight, appearance, and gender—internalized weight bias (IWB), body surveillance, and body shame—were positively and very strongly correlated with the degree of eating pathology (i.e., DE). Examining three key components of global eating pathology, both IWB and body shame predicted overvaluation of shape/weight, only IWB predicted body dissatisfaction, and only body surveillance predicted dietary restraint.

These results have two implications. First, as Martin-Wagar and Weigold (Citation2023) point out, IWB deserves more attention in treatments for EDs and, I would argue, in prevention. Second, if these findings are replicated with more ethnically and otherwise diverse samples of women with EDs, some important factors that predict one significant aspect of DE, and by extension, a central feature of certain EDs (e.g., dietary restriction), may not predict other transdiagnostic features (e.g., overvaluation of weight/shape and body dissatisfaction). Moreover, certain risk factors that are specific to EDs (vs. non-specific in relation to psychological disorders) may be transdiagnostic within the ED category, whereas others may not be.

Miles et al. (Citation2023) studied the interrelationships between three features of AN that are highly relevant to treatment—cognitive inflexibility, clinical perfectionism, and ED-specific rumination—as well as how they relate to specific symptoms of AN. For example, Miles et al. argue that cognitive inflexibility may contribute to maladaptive perfectionism in that the latter involves the calculation of self-worth based on a fierce, rigid pursuit of narrowly defined, very demanding goals, even (or especially) when there are clear negative consequences (fatigue, pain, and social isolation) for doing so.

A comparison of 15 young adult Australian women with current AN, 12 with a past AN diagnosis but who are now weight-restored, and 15 with no history of EDs or any mental illness revealed no significant differences in neuropsychological indicators of cognitive flexibility. However, as predicted and with large effect sizes, Miles et al. (Citation2023) found that the young women with any history of AN perceived themselves as having less cognitive flexibility while reporting significantly greater maladaptive perfectionism and ED-specific rumination. Those with current AN had significantly higher levels of clinical perfectionism than those recovered from AN. Interestingly, parallel mediation analyses indicated that level of subjective cognitive inflexibility, but not performance-related, had both a direct and a mediated relationship with ED psychopathology as measured by the EDE-Q. ED-specific rumination was a significant mediator, whereas clinical perfectionism was not.

Miles et al. (Citation2023) acknowledge that this unique study has limitations. Sample size was small, cognitive flexibility in everyday tasks was not assessed, and there was no control for comorbid conditions, notably depression, that may affect actual or subjective cognitive inflexibility. Nevertheless, and even though its focus is clinical, this study suggests that prevention of AN in, for example, adolescents who are at high risk because they have a parent with AN (Levine & Sadeh-Sharvit, Citation2023), would do well to address two variables: (1) the validity and costs of self-perceptions of inflexibility, rigidity, and resistance to change; and (2) ways of identifying and coping with rumination.

Srivastava et al. (Citation2023) examined the relationships between BMI and bulimia nervosa (BN) symptoms in 152 adults diagnosed with BN. Those with a BMI > 30 were significantly younger when they started dieting and reported significantly high levels of weight concerns, shape concerns, and cognitive dietary restraint. However, compared to those with a BMI < 25, they had a lower prevalence of both objective binge eating and driven exercise, but they had a higher prevalence of purging via vomiting or misuse of laxatives and/or diuretics. Interestingly, those with a BMI < 25 had a greater level of weight/shape concerns than those with a BMI between 25 and 30. These findings suggest that “Individuals with BN and comorbid obesity have distinct clinical characteristics” and that there is likely not a linear relationship between current BMI scores and the severity of BN symptoms and BN psychopathology. Given the finding that the heavier people with BN reported the most persistent and intense efforts at weight management, future studies of this type need to move beyond the simple BMI measure to consider variables such as IWB and self-objectification (see Martin-Wagar & Weigold, Citation2023, above), as well as the individual’s developmental history of weight suppression (Gorrell et al., Citation2019).

DE or DE features

The study by Le et al. (Citation2023) extended Le et al.'s (Citation2022) research on gendered racism, published last year in Eating Disorders (see also Levine, Citation2023, for a review). Working from an intersectional perspective, Le et al. (Citation2023) surveyed 180 Asian American sexual minority men ages 18–29 in order to examine the relationships between three forms of racism and DE, and whether emotional eating is a mediator of any significant correlations. Univariate and multivariate analyses indicated that, in this sample of Asian American men, sexual racism (being viewed within the sexual minority community as too feminine and thus unattractive to males) and internalized racism independently had significant positive but relatively small associations with DE. In contrast, gendered racism (experiences of being perceived as lacking masculine characteristics—e.g., not being dynamic, not being physically strong, not possessing leadership ability—based on one’s race) was not significantly correlated. Internalized racism’s, but not sexual racism’s, association with DE was partially mediated by level of emotional eating. Le et al. (Citation2023) study points to the need for more research on Asian-American sexual minority men. It also illuminates the value of an intersectional approach to investigating, including the use of prevention outcome studies, what are likely complex pathways connecting racist practices and the (dis)stress of racism with differing forms of DE (e.g., thinness-oriented vs. muscularity-disordered eating; Le et al., Citation2022) and EDs.

As shown in , negative body image and dietary restraint are prototypical features of DE. One undeniable influence on DE is various types of media. Instagram is a hugely popular image-based social media platform, accessed at least once each month by well over a billion people worldwide. One prominent type of content frequently posted on Instagram falls under the category of “fitspiration,” which Linardon (Citation2023) aptly describes as “images [that] typically depict lean women (or men) dressed in exercise gear, engaging in physical activity or eating healthy foods, sometimes superimposed with inspirational quotes” (p. 451).

Linardon (Citation2023) conducted an 8-month longitudinal online survey of several thousand Australian women (Mage = ~32 yrs; ~76.5% White) with body image/eating issues. As predicted, over time there was a reciprocal relationship between self-reported appearance comparisons to fitspiration images posted on Instagram and both negative body image and dietary restraint. That is, in this sample of women attuned to weight/shape management, regardless of whether or not “fitspiration” content inspires them or women in general to become fit(ter), one explicit purpose of any inspirational content, viewer self-comparison to the images, is linked prospectively to two aspects of DE. And the stronger this effect, the greater the subsequent tendency to compare one’s appearance with fitspiration images and even perhaps to seek them out for “self-improvement” purposes. Conversely, as expected, greater levels of body appreciation were associated prospectively with lower levels of those appearance comparisons (although this effect was not bi-directional) and their unhealthy correlates. These findings strengthen the rationale (see, e.g., Fardouly et al., Citation2018) for making the following a focus of prevention programs and clinical work that emphasize social media literacy: (a) reducing active and passive exposure to fitspiration images on Instagram; and (b) inhibition or moderation of self-comparison to fitspiration images on social media and elsewhere. Moreover, as Linardon points out, future experiments with social media literacy within a prevention framework are needed to establish whether the potentially important effects illuminated by this study are causal in nature.

Like social media, military service is a sociocultural factor that over the past 10–15 years has received increased attention from scientist-practitioners concerned about EDs and DE in emerging adult and young adult women. Not only are there regular assessments of height and weight to ensure women and men meet strict BMI requirements for continued service, there is also the specter of a prominent non-specific risk factor for psychopathology, including eating pathology: trauma followed by PTSD. For most people, thinking about this risk factor in the context of military service evokes the horrors of war or the vagaries of helicopter crashes or naval fires during training.

These are certainly very important clinical concerns. Nevertheless, they should not blind us to the high rates of sexual assault (SA) of women serving in the military, which is indisputably a bastion of masculinity and patriarchy. Gibson et al. (Citation2020) reported a conservative lifetime prevalence estimate for SA of 13% (i.e., 2 in 15), based on data from a sample of nearly 71,000 women ages 55 and older who had served in the U.S. military and had at least one clinical visit between 2005 and 2015.

In a sample of 98 women (Mage = ~39 yrs; ~69.5% White) who had served in the U.S. military, Sandhu et al. (Citation2023) found that, as predicted, SA by other military personnel (reported by 61% of this sample) was associated with greater levels of PTSD symptoms (large effect size) and DE (small to moderate effect size). Moreover, although the relationship between SA and total DE score on the Eating Attitudes Test was not mediated by level of PTSD symptoms, the correlation between SA and level of bulimic/food preoccupation symptoms and behaviors was fully mediated by the extent of PTSD symptoms. In the absence of longitudinal research, these findings must be considered preliminary, but they do reinforce the need to eliminate sexual assault in the military and, when it does occur, to take elevated arousal (e.g., anxiety), guilt, shame, and other PTSD symptoms very seriously as risk factors for immediate emotional regulation via binge eating and purging.

Another subgroup (if not subculture) at high (if not extremely high) risk for DE are transgender and/or nonbinary (TNB) people. Urban et al. (Citation2023) recruited 212 people (Mage = ~27 yrs; ~88% White) who resided in the USA, self-identified as currently struggling with DE or an ED, and described themselves in terms of one or more of the following gender identity categories: trans men (n = 80), trans women (n = 14), nonbinary (n = 146), and self-identified gender (n = 28). Applying an intersectional perspective analogous to that used by Le et al. (Citation2023; see above), regression analyses revealed that discrimination-based trauma symptoms and internalized transphobia, but not gender dysphoria (a form of body dissatisfaction), were highly significant and independent predictors of DE (Urban et al., Citation2023). Moreover, the relationship between discrimination-based trauma and DE was partially mediated by internalized transphobia, an effect that was intensified at (i.e., moderated by) higher levels of gender dysphoria.

In addition to their implications for competent provision of clinical services for TNB people, these nuanced findings, if replicable, add to those of Le et al. (Citation2023) in pointing out the need for indicated ED prevention programming for overlapping groups rendered at risk by virtue of their multiple, often fluid identities. These programs should acknowledge the various paths of influence by which multiple forms of trauma and discrimination power DE, while providing complementary development of protective factors. These include multiple forms of advocacy to reduce systemic minority stress and increase social justice.

In regard to theme of the multifaceted effects of multiple forms of racism, the discussion section of the Le et al. (Citation2023) article reviewed above proposed that different profiles of multiple forms of racism likely result in or reinforce different motives for DE. One well-studied motive for DE is drive for thinness, whereas a more recent focus of research is a drive for muscularity and low(er) body fat levels (i.e., leanness). Admittedly, although the prototypical definition of DE shown in has elements of both motivational orientations, it is biased toward thinness-oriented forms of DE such as dietary restraint and fear of weight gain. Based on their review of the literature, Messer et al. (Citation2023), including Linardon (see above) as supervising researcher, note that the principal manifestations of muscularity-oriented disordered eating (MODE) include “overconsumption of protein-based foods, frequent eating (every 2–3 hours, sometimes during the middle of the night), elimination of fats and/or carbohydrate-based foods, liquefying ingredients to increase caloric intake, periodically engaging in ‘cheat’ meals to boost metabolic rate, and maintaining continual access to pre-planned foods” (p. 162).

Using primarily online health and wellness platforms, Messer et al. (Citation2023) recruited a community-based sample of 1136 adult women and 185 men to complete online surveys. For both men and women, univariate correlations between scores on the Muscularity-Oriented Eating Test (MOET; Murray et al., Citation2019) and scores on the EDE-Q subscales of dietary restraint (+.72/+.74) and fear of weight gain (+.47/+.54) were substantial. Nevertheless, for both men and women MODE, as measured by the MOET, accounted for a significant proportion of variance (8–10%) in DE-related functional impairment beyond that attributable to thinness-oriented DE symptoms. And for women, but not men, MODE also accounted for unique variance (3%) in symptoms of depression and anxiety.

There are three important implications of these findings. First, the substantial overlap in psychopathology and functional impairment between thinness-oriented DE and muscularity-oriented DE is deserving of network analysis using better measures of fear of fat and, as Messer et al. (Citation2023) acknowledge, taking into account the MOET’s inclusion of dietary restraint. The findings of this research will guide revision of the preliminary proposal for categorization of DE shown in . Second, these two manifestations of eating psychopathology differ in meaningful ways and likely constitute different stages in and/or risk factors for different outcomes, such as the established relationship between MODE and muscularity-oriented body dysmorphic disorder. Third, although longitudinal research is needed, within prominent subgroups (e.g., athletes, body builders, aspiring professional wrestlers), including Asian American Sexual Minority Men (Le et al., Citation2023, reviewed above), MODE is almost certainly an important focus for selective and indicated prevention programs that need to be developed (Messer et al., Citation2023).

Developing, evaluating, and disseminating prevention programs

Let us return for a moment to . Illumination of putative causal risk and protective factors informs the development and initial testing of innovative prevention. A pilot study, which may or may not have control conditions, evaluates feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes in order to determine whether or not a program is practical, is likely to produce positive effects, and is extremely unlikely to generate unintended negative effects. If so, further evaluation is warranted. Prevention science distinguishes between a program’s efficacy under ideal and highly controlled conditions, and its effectiveness when implemented by various stakeholders within communities that differ from the settings in which pilot and efficacy studies were conducted. As such, effectiveness research also addresses factors pertaining to dissemination and up-scaling of a program in order to reach wider and more diverse groups of people. Eating Disorders did not publish any pilot studies, efficacy studies, or effectiveness research in 2023.

Conclusions and implications

I hope the 2024 issues of Eating Disorders, unlike this past year’s, will feature at least one article in the important categories of broad prevention-related issues (theory, methodology, and ethics), protective factor research, advocacy for prevention-oriented policies (all of which were also absent in 2022), and, of course, evaluations of the first three stages of prevention programming: pilot, efficacy, and effectiveness/dissemination (see ). Regardless, as a group, the 16 articles published in Eating Disorders in 2023 illustrate both the value and the complexity of the opportunities and challenges that emerge at several important phases of the research cycle involved in preventing DE and EDs: (1) elucidating the fundamental components, the correlates, and the comorbid disorders (e.g., depression and substance abuse) that can alert family members and primary care providers to their presence and that render them serious conditions worthy of prevention efforts at multiple levels; (2) challenging stereotypes about who is and is not at risk, as well as who is and is not affected by certain risk factors; and (3) investigating the networks involved in how features of DE and EDs are correlated within the syndromes, which risk factors are part of pathways to which features, and for whom, as determined by the intersections of various biopsychosocial factors.

The 16 prevention-oriented articles in Eating Disorders in 2023 also advance our understanding in four significant and interrelated ways, while highlighting future directions for theory and research. First, while DE is a major construct as a risk factor for EDs and as a major public health concern in and of itself, more attention is needed to defining and measuring disordered eating (). This goal is likely to become even more important as risk factor researchers and prevention program designers turn their attention to subgroups of people whose needs, for whatever reasons, have not traditionally been addressed by the eating disorder fields. These include, for example, Asian American sexual minority men, adult women who have begun binge eating after age 40, women in the military, and men and women whose disordered eating is muscularity-oriented.

The second way that the articles in this year’s issues of Eating Disorders advance the field of prevention is by encouraging us to apply more nuanced theories, and thus assessments, of risk and vulnerability as these apply to “at-risk” groups. There is a clear need to move away from general statements about, for example, marginalized groups (e.g., sexual minority men, people in the transgender/nonbinary communities) at risk and toward elaboration of the specific sources of risk operating in those marginalized groups (embedded within larger cultural influences) and the pathways by which these result in particular features of DE and EDs.

Although it is hardly a new point of emphasis (see in particular Jacobi et al., Citation2004), the third advancement is an implicit insistence that we revisit the complex matter of clarifying the constructs we use in understanding—and in the name of prevention, disrupting—the natural course of the development of DE and EDs. What are the distal sources of specific and non-specific risk emerging in childhood and early adolescence? What are more proximal sources of risk (in some cases the clear stressors, even trauma) that generate features or sets of features of DE that may be the early stages of EDs? Which of these very proximal stressors might well be considered “triggers” of the development of DE and/or EDs—and which of the features of DE (e.g., feeling bloated after eating) are the most useful (to, parents, physicians, teachers, coaches) early “warning signs” of EDs? Answering these questions will require a return to large scale retrospective case-controlled studies and, most importantly, longitudinal research. These longitudinal studies will need to be attuned to the ways in which, for example, distal and proximal sources of negative body image institute vicious cycles of exposure to social media, social comparison, body change attempts, worsening body image, greater if not obsessive attention to social media and other social cues appearance, and so on.

Finally, the articles in this year’s issues of Eating Disorders leave no doubt that research is needed to clarify the risk factor status and then utility for prevention programming of variables that previously have been almost totally ignored. Pending longitudinal and case-controlled retrospective studies (Jacobi et al., Citation2004), the likely candidates for selective and indicated prevention according to the articles reviewed above are listed in . As I noted in last year’s review (Levine, Citation2023), research, extending to prevention, with these variables will likely facilitate very positive steps in multidimensional prevention programs for the previously overlooked groups listed above.

Table 3. Eight putative DE and/or ED risk factors deserving of more attention prevention scientists.

Implications for prevention practice

The phasic prevention cycle facilitates understanding of forms of prevention research and their relationship to the Mental Health Intervention Spectrum linking health promotion, prevention, early identification and referral, and treatment

Disordered eating is a major construct as a risk factor for eating disorders and as a public health concern in and of itself. Consequently, more attention is needed to defining and measuring disordered eating.

Risk factor research toward the construction of selective and indicated prevention programs for diverse at-risk groups of people needs to address, from an intersectional framework, a broad range of factors beyond negative body image and internalization of beauty ideals.

To expand and improve our prevention programs and to shape effective prevention-oriented advocacy and social policy, the field in general and Eating Disorders in particular needs more scholarship in the form of critical reviews and meta-analyses, protective factor research, program development and outcome evaluations, and case studies of multi-step activism at the local, state (province, region), and national levels.

Disclosure statement

The author receives royalties from the books co-authored and co-edited with L. Smolak.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. With the exception of some minor changes and the quotation from Levine and Smolak (Citation2021), the text describing key concepts and frameworks—and the later section on developing, evaluating, and disseminating prevention programs—is reproduced verbatim from last year’s review (Levine, Citation2023).

References

- Abild, C. B., Jensen, A. L., Lassen, R. B., Thyssen Vestergaard, E., Meldgaard Bruun, J., Kristensen, K., Klinkby Støving, R., & Clausen, L. (2023). Patients’ perspectives on screening for disordered eating among adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 28(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-023-01539-2

- Alhaj, O. A., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Sweidan, D. H., Saif, Z., Khudhair, M. F., Ghazzawi, H., Nadar, M. S., Alhajeri, S. S., Levine, M. P., &Jahrami, H. A. (2022). The prevalence and risk factors of screen-based disordered eating among university students: A global systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(8), 3215–3243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01452-0

- Al Mestaka, N., Alneyadi, A., AlAhbabi, A., AlMatrushi, A., AlSaadi, R., & Alketbi, L. B. (2023). Prevalence of probable eating disorders and associated risk factors in children and adolescents aged 5–16 years in Al Ain City, United Arab Emirates: Observational case–control study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00840-w

- AlShebali, M., Becker, C., Kellett, S., AlHadi, A., & Waller, G. (2023). Dissonance-based prevention of eating pathology in non-western cultures: A randomized controlled trial of the body project among young Saudi adult women. Body Image, 45, 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.03.014

- *Amiri, S., & Khan, M. A. B. (2023). Prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, suicide mortality in eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eating Disorders, 31(5), 487–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2196492

- Atkinson, M. J., Parnell, J., & Diedrichs, P. C. (2023). Task shifting eating disorders prevention: A pilot study of selective interventions adapted for teacher-led universal delivery in secondary schools. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 57(2), 327–340. Advance online publication [open access]. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24100

- Austin, S. B. (2016). Accelerating progress in eating disorders prevention: A call for policy translation research and training. Eating Disorders, 24(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2015.1034056

- Averett, S., Terrizzi, S., & Wang, Y. (2017). The effect of sorority membership on eating disorders, body weight, and disordered-eating behaviors. Health Economics, 26(7), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/HEC.3360

- *Babbott, K. M., Cavadino, A., Brenton-Peters, J., Consedine, N. S., & Roberts, M. (2023). Outcomes of intuitive eating interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eating Disorders, 31(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2030124

- Barakat, S., McLean, S. A., Bryant, E., Le, A., Marks, P., National Eating Disorder Research Consortium,Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2023). Risk factors for eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00717-4

- Barnhart, W. R., Cui, T., Zhang, H., Cui, S., Zhao, Y., Lu, Y., & He, J. (2023). Examining an integrated sociocultural and objectification model of thinness- and muscularity-oriented disordered eating in Chinese older men and women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(10), 1875–1886. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24017

- Becker, C. B. (2016). Our critics might have valid concerns: Reducing our propensity to conflate. Eating Disorders, 24(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2015.1113833

- Biglan, A., Prinz, R. J., & Fishbein, D. (2023). Prevention science and health equity: A comprehensive framework for preventing health inequities and disparities associated with race, ethnicity, and social class. Prevention Science, 24(4), 602–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01482-1

- Byrne, S. E., Basten, C. J., & McAloon, J. (2023). The development of disordered eating in male adolescents: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Adolescent Research Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00217-9

- Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. Basic Books.

- Carrard, I., Cekic, S., & Bucher Della Torre, S. (2023). A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the acceptability and effectiveness of two eating disorders prevention interventions: The HEIDI BP-HW project. BMC Women’s Health, 23, 446. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02607-6

- Chatwin, H., Holde, K., Yilmaz, Z., Larsen, J. T., Albiñana, C., Vilhjálmsson, B. J., Mortensen, P. B., Thornton, L. M., Bulik, C. M., & Petersen, L. V. (2023). Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: A population-based investigation of sex differences in polygenic risk and early life exposures. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(9), 1703–1716. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23997

- Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults [National Research Council & Institute of Medicine of the National Academies]. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. The National Academies Press.

- D’Adamo, L., Ghaderi, A., Rohde, P., Gau, J. M., Shaw, H., & Stice, E. (2023). Evaluating whether a peer-led dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program prevents onset of each eating disorder type. Psychological Medicine, 53(15), 7214–7221. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723000739

- Dahill, L. M., Hay, P., Morrison, N. M. V., Touyz, S., Mitchison, D., Bussey, K., & Mannan, H. (2023). Associations between parents’ body weight/shape comments and disordered eating amongst adolescents over time—A longitudinal study. Nutrients, 15(6), 1419. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061419

- Davies, H. L., Hübel, C., Herle, M., Kakar, S., Mundy, J., Peel, A. J., Ter Kuile, A. R., Zvrskovec, J., Monssen, D., Lim, K. X., Davies, M. R., Palmos, A. B., Lin, Y., Kalsi, G., Rogers, H. C., Bristow, S., Glen, K., Malouf, C. M., Kelly, E. J., Purves, K. L., … Breen, G. (2023). Risk and protective factors for new‐onset binge eating, low weight, and self‐harm symptoms in 35,000 individuals in the UK during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23834

- *Doney, F. M., Lee, J., Sarkisyan, A., Compte, E. J., Nagata, J. M., Pederson, E. R., & Murray, S. B. (2023). Eating disorder risk among college sorority and fraternity members within the United States. Eating Disorders, 31(5), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2188005

- Dunker, K. L. L., Berbert de Carvalho, P. H., & Amaral, A. C. (2023). Eating disorders prevention programs in Latin American countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(4), 691–707. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23916

- Faller, J., Perez, J. K., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. L., Engel, L., Lee, Y. Y., Le, P. H., & Le, L. K.-D. (2023). Economic evidence for prevention and treatment of eating disorders: An updated systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders. Advance online publication [open access]. 57(2), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24113

- Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. R. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1380–1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Balantekin, K. N., Eichen, D. M., Graham, A. K., Monterubio, G. E., Sadeh-Sharvit, S., Goel N. J., Flatt R. E., Saffran K., Karam, A. M., Firebaugh, M.-L., Trockel, M., Taylor, C. B., & Wilfley, D. E. (2019). Screening and offering online programs for eating disorders: Reach, pathology, and differences across eating disorder status groups at 28 U.S. universities. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(10), 1125–1136. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23134

- Forney, K. J., Horvath, S. A., Pucci, G., & Harris, E. R. (2023). Fullness and bloating as correlates of eating pathology: Implications for screening. Eating Disorders, 31(4), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2141705

- Garbett, K. M., Haywood, S., Craddock, N., Gentili, C., Nasution, K., Saraswati, L. A. Medise, B. E. Paul, W. Diedrichs, P. C., & Williamson, H. (2023). Evaluating the efficacy of a social media–based intervention (Warna-Warni Waktu) to improve body image among young Indonesian women: Parallel randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e42499. https://doi.org/10.2196/42499.

- Ghazzawi, H. A., Nimer, L. S., Sweidan, D. H., Alhaj, O. A., Abu Lawi, D., Amawi, A. T., Levine, M. P., & Jahrami, H. (2023). The global prevalence of screen-based disordered eating and associated risk factors among high school students: Systemic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00849-1

- Gibson, C. J., Maguen, S., Xia, F., Barnes, D. E., Peltz, C. B., & Yaffe, K. (2020). Military sexual trauma in older women veterans: Prevalence and comorbidities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(1), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05342-7

- Gorrell, S., Reilly, E. E., Schaumberg, K., Anderson, L. M., & Donahue, J. M. (2019). Weight suppression and its relation to eating disorder and weight outcomes: A narrative review. Eating Disorders, 27(1), 52–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1499297

- Hay, P., Aouad, P., Le, A., Marks, P., Maloney, D., National Eating Disorder Research Consortium, Touyz, S., Maguire, S., Brennan, L., Bryant, E., Byrne, S., Caldwell, B., Calvert, S., Carroll, B., Castle, D., Caterson, I., Chelius, B., Chiem, L., … Touyz, S. (2023). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Population, prevalence, disease burden and quality of life informing public policy in Australia—A rapid review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00738-7

- He, J., Barnhart, W. R., Zhang, Y., Han, J., Wang, Z., Cui, S., & Nagata, J. M. (2023). Muscularity teasing and its relations with muscularity bias internalization, muscularity-oriented body dissatisfaction, and muscularity-oriented disordered eating in Chinese adult men. Body Image, 45, 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.04.003

- Hendricks, E., Jenkinson, E., Falconer, L., & Griffiths, C. (2023). How effective are psychosocial interventions at improving body image and reducing disordered eating in adult men? A systematic review. Body Image, 47 101612. Advance online publication [open access]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.08.004

- Jacobi, C., Hayward, C., de Zwaan, M., Kraemer, H. C., & Agras, W. S. (2004). Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin, 130(1), 19–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19

- *Kilpela, L. S., Marshall, V. B., Hooper, S. C., Becker, C. B., Keel, P. K., LaCroix, A. Z., Musi, N., & Espinoza, S. E. (2023). Binge eating age of onset, frequency, and associated emotional distress among women aged 60 years and over. Eating Disorders, 31(5), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2192600

- Koreshe, E., Paxton, S., Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Bryant, E., Le, A., Maloney, D., Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2023). Prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00758-3

- Korsak, E. (2023). Characteristics of anorexia prevention programmes. A systematic review. Kultura i Edukacja, 140(2), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.15804/kie.2023.02.02

- Kraemer, H. C., Kazdin, A. E., Offord, D. R., Kessler, R. C., Jensen, P. S., & Kupfer, D. J. (1997). Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009

- Le, T. P., Bradshaw, B. T., Pease, M., & Kuo, L. (2022). An intersectional investigation of Asian American men’s muscularity-oriented disordered eating: Associations with gendered racism and masculine norms. Eating Disorders, 30(5), 492–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2021.1924925

- *Le, T. P., Jin, L., & Kang, N. (2023). Sexual, gendered, and internalized racism’s associations with disordered eating among sexual minority Asian American men: Emotional eating as mediator. Eating Disorders, 31(6), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2201024

- Levine, M. P. (2023). Prevention of eating disorders: 2022 in review. Eating Disorders, 31(2), 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2191476

- Levine, M. P., & Sadeh-Sharvit, S. (2023). Preventing eating disorders and disordered eating in genetically vulnerable, high‐risk families. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(3), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23887

- Levine, M. P., & Smolak, L. (2016). The role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating. Eating Disorders, 24(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2015.1113826

- Levine, M. P., & Smolak, L. (2021). The prevention of eating problems and eating disorders: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- *Lin, J. A., Jhe, G., Adhikari, R., Vitagliano, J. A., Rose, K. L., Freizinger, M., & Richmond, T. K. (2023). Triggers for eating disorder onset in youth with anorexia nervosa across the weight spectrum. Eating Disorders, 31(6), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2201988

- *Linardon, J. (2023). Investigating longitudinal bidirectional associations between appearance comparisons to fitspiration content on Instagram, positive and negative body image, and dietary restraint. Eating Disorders, 31(5), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2190973

- Mahon, C., Hamburger, D., Yager, Z., Almaraz, M., Mooney, J., Tran, T., O’Dowd, O., Bauert, L., Smith, K. G., Gomez-Trejo, V., & Webb, J. B. (2023). Pilot feasibility and acceptability trial of BE REAL’s BodyKind: A universal school-based body image intervention for adolescents. Body Image, 47, 101636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.101636

- Martin, M., Davis, A., Pigott, A., & Cremona, A. (2023). A scoping review exploring the role of the dietitian in the identification and management of eating disorders and disordered eating in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clinical Nutrition, 58, 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.10.038

- *Martin-Wagar, C. A., & Weigold, I. K. (2023). Internalized stigma as a transdiagnostic factor for women with eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 31(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2095481

- McCabe, M., Alcaraz-Ibanez, M., Markey, C., Sicilia, A., Rodgers, R. F., Aimé, A., Dion, J., Pietrabissa, G., Lo Coco, G., Caltabiano, M., Strodl, E., Bégin, C., Blackburn, M., Castelnuovo, G., Granero-Gallegos, A., Gullo, S., Hayami-Chisuwa, N., He, Q., Maïano, C., Manzoni, G. M., … Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2023). A longitudinal evaluation of a biopsychosocial model predicting BMI and disordered eating among young adults. Australian Psychologist, 58(2), 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2023.2181686

- McClure, Z., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Messer, M., & Linardon, J. (2023). Predictors, mediators, and moderators of response to digital interventions for eating disorders: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24078

- *Messer, M., Duxson, S., Diluvio, P., McClure, Z., & Linardon, J. (2023). The independent contribution of muscularity-oriented disordered eating to functional impairment and emotional distress in adult men and women. Eating Disorders, 31(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2086728

- *Miles, S., Nedeljkovic, M., & Phillipou, A. (2023). Investigating differences in cognitive flexibility, clinical perfectionism, and eating disorder-specific rumination across anorexia nervosa illness states. Eating Disorders, 31(6), 610–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2206751

- Mills, R., Hyam, L., & Schmidt, U. (2023). A narrative review of early intervention for eating disorders: Barriers and facilitators. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 14, 217–235. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S415698

- Mitchison, D., Wang, S. B., Wade, T., Haynos, A. F., Bussey, K., Trompeter, N., Lonergan, A., Tame, J., & Hay, P. (2023). Development of transdiagnostic clinical risk prediction models for 12-month onset and course of eating disorders among adolescents in the community. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(7), 1406–1416. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23951

- Murray, S. B., Brown, T. A., Blashill, A. J., Compte, E. J., Lavender, J. M., Mitchison, D., Mond, J. M., Keel, P. K., & Nagata, J. M. (2019). The development and validation of the Muscularity-Oriented Eating Test: A novel measure of muscularity-oriented disordered eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(12), 1389–1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23144

- Nagata, J. M., Chu, J., Cervantez, L., Ganson, K. T., Testa, A., Jackson, D. B., Murray, S. B., & Weiser, S. D. (2023). Food insecurity and binge-eating disorder in early adolescence. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(6), 1233–1239. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23944

- Okoya, F. T., Santoso, M., Raffoul, A., Atallah, M. A., & Austin, S. B. (2023). Weak regulations threaten the safety of consumers from harmful weight-loss supplements globally: Results from a pilot global policy scan. Public Health Nutrition, 26(9), 1917–1924. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023000708

- Osborne, E., Ainsworth, B., Chadwick, P., & Atkinson, M. (2023). The role of emotion regulation in the relationship between mindfulness and risk factors for disordered eating: A longitudinal mediation analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(2), 458–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23849

- Piran, N., Counsell, A., Teall, T. L., Komes, J., & Evans, E. H. (2023). The developmental theory of embodiment: Quantitative measurement of facilitative and adverse experiences in the social environment. Body Image, 44, 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.12.005

- Radunz, M., Ali, K., & Wade, T. D. (2023). Pathways to improve early intervention for eating disorders: Findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(2), 314–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23845

- Raffoul, A., Turner, S. L., Salvia, M. G., & Austin, S. B. (2023). Population-level policy recommendations for the prevention of disordered weight control behaviors: A scoping review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(8), 1463–1479. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23970

- Richardson, D. B., Dukes, O., & Tchetgen Tchetgen, E. J. (2023). Estimating the effect of a treatment when there is nonadherence in a trial. American Journal of Epidemiology, 192(10), 1772–1780. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwad141

- Rodgers, R. F., Laveway, K., Campos, P., & de Carvalho, P. H. B. (2023). Body image as a global mental health concern. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10(e9), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.2

- Rohde, P., Bearman, S. K., Pauling, S., Gau, J. M., Shaw, H., & Stice, E. (2023). Setting and provider predictors of implementation success for an eating disorder prevention program delivered by college peer educators. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 50(6), 912–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01288-5

- *Sandhu, D., Dougherty, E. N., & Haedt-Matt, A. (2023). PTSD symptoms as a potential mediator of associations between military sexual assault and disordered eating. Eating Disorders, 31(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2133586

- Schneider, J., Matheson, E. L., Tinoco, A., Gentili, C., White, P., Boucher, C., Silva-Breen, H., Goorevich, A., Diedrichs, P. C., & LaVoi, N. M. (2023). Body confident coaching: A pilot randomized controlled trial evaluating the acceptability of a web-based body image intervention for coaches of adolescent girls. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 36(2), 231–256. Advance online publication [open access]. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2023.2212023

- Sharma, A., & Vidal, C. (2023). A scoping literature review of the associations between highly visual social media use and eating disorders and disordered eating: A changing landscape. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00898-6

- Smolak, L. (2012). Risk and protective factors in body image problems: Implications for prevention. In G. L. McVey, M. P. Levine, N. Piran, & H. B. Ferguson (Eds.), Preventing eating-related and weight-related disorders: Collaborative research, advocacy, and policy change (pp. 199–222). Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Smolak, L., & Levine, M. P. (2015). Body image, disordered eating, and eating disorders: Connections and disconnects. In L. Smolak & M. P. Levine (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of eating disorders (vol. 1): Basic concepts and foundational research (pp. 3–10). John Wiley & Sons.

- *Srivastava, P., Presseller, E. K., Chen, J. Y., Clark, K. E., Hunt, R. A., Clancy, O. M., Juarascio, A. S., & Manasse, S. (2023). Weight status is associated with clinical characteristics among individuals with bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 31(5), 415–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2145258

- Terhoeven, V., Nikendei, C., Bountogo, M., Friederich, H.-C., Ouermi, L., Sié, A. Harling, G. Bärnighausen, T. (2023). Exploring risk factors of drive for muscularity and muscle dysmorphia in male adolescents from a resource-limited setting in Burkina Faso. Science Reports, 13(1), 20140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46863-w

- *Thiel, A. M., Spoor, S. P., McGinnis, B. L., & De Young, K. P. (2023). Examining the association of eating psychopathology with suicidality: Comparing cross-sectional and longitudinal tests of interpersonal-psychological mediators. Eating Disorders, 31(4), 320–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2135719

- Thompson, K. A., Bauman, V., Sunderland, K. W., Thornton, J. A., Schvey, N. A., Moyer, R., Sekyere N. A., Funk W., Pav V., Brydum R., Klein D. A., Lavender J. M., & Tanofsky-Kraff, M. (2023). Incidence and prevalence of eating disorders among active duty US military-dependent youth from 2016 to 2021. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(10), 1973–1982. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.24025

- Tschampl, C. A., Lee, M. R., Raffoul, A., Santoso, M., & Austin, S. B. (2023). Economic value of initial implementation activities for proposed ban on sales of over-the-counter diet pills and muscle-building supplements to minors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine Focus, 2(3), 100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2023.100103

- Unikel Santoncini, C., Barajas Márquez, M. W., Díaz de León Vázquez, C., Parra Carriedo, A., Rivera Márquez, J. A., & Bilbao y Díaz Gutiérrez, M., Morcelle, G., & Díaz Gutiérrez, M. (2023). Sex and body mass index differences after one-year follow-up of an eating disorders risk factors universal prevention intervention in university students in Mexico City. Salud Mental, 46(3), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2023.019

- *Urban, B., Knutson, D., Klooster, D., & Soper, J. (2023). Social and contextual influences on eating pathology in transgender and nonbinary adults. Eating Disorders, 31(4), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2022.2135715

- *Webster, A. E., Zickgraf, H. F., Gideon, N., Mond, J. M., Serpell, L., Lane-Loney, S. E., & Essayli, J. H. (2023). Preliminary validation of the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire-Short Parent Version (EDE-QS-P). Eating Disorders, 31(6), 651–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2023.2218675