Abstract

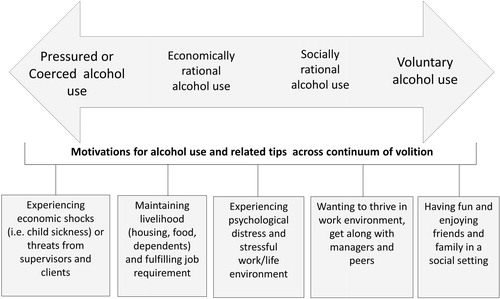

Background: Female entertainment workers (FEWs) in Cambodia work in predominantly alcohol-based venues and therefore may face occupational risks. Studies have suggested that FEWs are pressured to consume alcohol while at the workplace, which may have adverse health outcomes. This study aims to explore the experiences of alcohol use among FEWs in Cambodia. Methods: Twenty-seven focus group discussions (FGDs) with FEWs were conducted across five sites in four provinces in Cambodia. FGD participants were FEWs who worked at entertainment venues, including karaoke TV bars, beer gardens, and massage parlors, as well as women who worked as on-call or street-based sex workers, and women across entertainment venues who were parenting. Results: The authors modified a conceptual model to create a framework based on the major themes identified within the FGDs on autonomy in alcohol use among FEWs. The framework and thematic components highlight the continuum of autonomy from pressured or coerced alcohol use to, economically or socially rational alcohol use to voluntary alcohol use. Factors that impacted alcohol use across the spectrum include experiencing an economic shock, needing to maintain a livelihood, experiencing psychological distress, having the desire to thrive in employment environment and drinking socially for personal enjoyment. Conclusion/Importance: Much of the motivation behind alcohol use is related to the need for economic security. For women who do not have other employment or income-generating options, individual behavior change programing is unlikely to be effective. Structural changes are needed to improve the health and safety of FEWs in Cambodia.

Introduction

Entertainment establishments such as karaoke TV bars (KTV), beer gardens and nightclubs employ over 38,000 female entertainment workers (FEWs) in Cambodia (NCHADS, Citation2017) and serve as the main locations where clients pursue flirtatious conversation, drinks and sometimes sexual activity in exchange for money (Couture et al., Citation2016; Hsu, Howerd, Torreinte, & Por, Citation2016). These venues are not considered brothels but have seen an increase in both clients and female sex workers since the formerly government-sanctioned brothel system became illegal, with the passing of a law intended to suppress human trafficking and sexual exploitation in 2008 (Maher et al., Citation2011; Rojanapithayakorn & Phalla, Citation2000; Wong et al., Citation2018).

Occupational hazards for women working in entertainment venues are a growing concern. Occupational hazards reported by FEWs in Cambodia range from low or withheld wages to unwanted touching, verbal abuse, physical violence and forced abortions (Hsu et al., Citation2016; Maher et al., Citation2011). Another form of workplace harassment for FEWs is the pressure by employers for workers to drink alcohol as a way to both entice clients to drink more and to encourage FEWs to be more flirtatious with customers (Couture et al., Citation2016; Zaller et al., Citation2014).

Excessive drinking makes entertainment work environments even more risky for FEWs as alcohol use is a top risk factor for contracting HIV (Hsu et al., Citation2016; Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufaman, Cain & Jooste, Citation2007; Kumar, Citation2003; Li, Li, & Stanton, Citation2010). While the HIV prevalence in the general population in Cambodia has declined, FEWs continue to be at high risk of the infection (KHANA, Citation2017). Currently, the prevalence of HIV among FEWs who engage in sexual activity is estimated at 3.2% (Mun et al., Citation2017). Alcohol use plays a critical role in a decreased ability for FEWs to negotiate condom use due to impaired judgment and decreased inhibition (Chiao, Morisky, Rosenberg, Ksobiec & Malow, Citation2006; Couture et al., Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2016; Kumar, Citation2003, Yang et al., Citation2013). Drinking alcohol has a consistent and strong correlation with HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Li et al., Citation2010; Shuper et al., Citation2010) and yet is a daily routine for FEWs and their clients in Cambodia (Couture et al., Citation2016; Maher et al., Citation2011).

The frequency and the amount of alcohol use at work is difficult to ascertain with complete accuracy. It is estimated that 62% of FEWs drink alcohol every day at work and about half of those who drink daily (49.9%) report drinking more than 55 units in a week (cans or bottles for beers and glasses for wines and heavy alcoholic drinks) (Mun et al., Citation2017). While recommendations or limitations around alcohol use is not available globally, excessive drinking for women is defined in the United States as consuming four or more alcoholic drinks during a single occasion (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2018). It should be noted that this categorization is from a Western perspective and is not inclusive of cultural differences and different cultural-specific gender norms related to alcohol.

Forced drinking of FEWs at entertainment venues is happening in the context of the limited or restricted ability of workers in Cambodia to exercise the right to organize and bargain collectively for improved work conditions (Human Rights Watch, Citation2015). There are few or no legal channels to voice grievances or advocate for their interests. In the recent past, workers’ rights demonstrations have resulted in deadly clashes with police (British Broadcasting Company, 2014). While workers in the entertainment industry have seen some progress in terms of occupational safety and health regulations with the passing of new labor laws in 2014, challenges to implementation of the laws, including the resources to hire and train enough labor inspectors, have delayed many of the benefits of the legislations (Hsu et al., Citation2016).

While there is some literature and knowledge about alcohol use in the workplace among FEWs, there is a gap in information on the scope and nature of the pressure to drink as well as the strategies and coping mechanism women use to manage their workplace experiences (Li et al., Citation2010). This study employs focus group discussions (FGDs) to explore themes related to pressure, coercion, and autonomy in alcohol use among FEWs in Cambodia.

Materials and methods

This study is part of a larger intervention development process for the Mobile Link project, implemented by KHANA, based in Phnom Penh. The Mobile Link project is an operational mobile health research project in Cambodia that aims to engage FEWs, and link them to the existing prevention, care and treatment services in the country. The overall goal of the Mobile Link study is to deploy and rigorously evaluate the efficacy of the Mobile Link, an innovative intervention to engage young FEWs in Cambodia through frequent automated voice calls (VCs) or text messages that link them to existing services including HIV testing. A 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT) is underway to evaluate the Mobile Link intervention, with two arms of 300 FEWs each. More details about the Mobile Link project can be found in the published protocol (Brody et al., Citation2018).

Prior to rollout of the RCT, a rigorous formative research project was undertaken to explore prioritized health issues among FEWs in order to ensure that the intervention was relevant and desired. Using FGDs, in-depth interviews, and participatory validation workshops, the research team gathered information on knowledge, attitudes and practices related to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) among FEWs in four provinces in Cambodia to inform the Mobile Link message creation and program implementation. A series of FGDs covering a wide range of topics were conducted across each of the five intervention sites, across selected provinces.

Data collection tool and procedures

Based on a review of the literature and discussion with program teams, a FGD guide was developed that covered a wide range of SRH topics including HIV, gender-based violence and substance use. A two-day workshop was conducted to train seven data collectors and five community lay health workers (one peer data collector and one community lay health worker within each site) on the objectives of the overall project, how to use the FGD guide tool and basics of conducting FGDs – especially with vulnerable populations. In addition, the FGD guide was piloted in each province with a FGD of women recruited predominantly from karaoke bars, and these data were included in the analysis. Facilitators were instructed to follow the semi-structured guide, while allowing for ability to follow relevant conversation threads. Following each pilot FGD, the project team debriefed on the recruitment, the tool and the implementation and what should be improved. Notes were taken and incorporated into the final versions of the FGD guides.

Focus group guide

Based on studies exploring alcohol use in Cambodia and neighboring countries, the team developed four questions on alcohol use. Because the FGD guides were created to explore a range of topics, only 3–5 questions per topic were included. Also, the purpose of collecting information was explicitly to develop messages for the Mobile Link program, so the questions were developed for that purpose, rather than to directly explore the experiences of alcohol use in entertainment venues among FEWs. The questions and initial probes for alcohol use were:

Have you ever used alcohol?

Probe: What are the reasons that you drink alcohol?

Have you ever been forced to drink?

Probe: Who forces you to drink alcohol? In what ways do they force you?

Probe: How does drinking impact your pay?

What are the effects from drinking alcohol?

Probe: Physical effects? Emotional effects?

Probe: What happens if you have to take medication like an antibiotic?

Do you know any good tips for secretly getting rid of alcohol that you are supposed to drink or ways to stay in control and not get drunk?

The last question was included with the intention of gathering actual tips and ideas that FEWs use to avoid intoxication, in order to inform the Mobile Link intervention messages.

Sampling and site selection

Based on the 2016 the most recent National Integrated Biological and Behavioral Survey (IBBS), the provinces with the highest HIV prevalence among FEWs included: Phnom Penh, Battambang and Banteay Meanchey (3+%), (Mun et al., Citation2017). Due to the intention to reach the most-at-risk population, the research team purposively selected to conduct the FGDs in these three provinces, as well as Siem Reap, which has been identified as a high-burden area despite having a lower HIV prevalence. The formative research was implemented in partnership with community-based organizations: KHEMARA and Save Incapacity Teenager (SIT) in Phnom Penh, with Cambodian Women for Peace and Development (CWPD) in Battambang and Siem Reap and with Partners for Development (PFD) in Banteay Meanchey.

A two-stage cluster design was employed whereby entertainment venues were randomly selected from a list of all entertainment venues in the province by venue type (karaoke bars, massage parlors, bar/restaurants) from each operational district, and then outreach workers purposively recruited FEWs to participate. The average age of participants in the FGDs was 24 years old. Within each venue, specific recruitment strategies were developed that were tailored to that venue and a uniform screening tool was utilized to identify eligible participants. Eligibility requirements for participation included:

Working at an entertainment venue in Cambodia OR self-identifying as an entertainment worker OR actively exchanging sex for money/gifts;

Aged between 18–30 years;

Being currently sexually active, defined as having engaged in oral, vaginal or anal sex in the past three months;

Owning a personal and private mobile phone;

Knowing how to retrieve voice mails (VM) or retrieve and read text messages on mobile phones in Khmer or Khmer with English alphabet;

Being able to provide a written informed consent.

Data collection

Data collection occurred over a period of three weeks with concurrent data transcription and translation. FGDs were separated by venue type, with the exception of parenting-specific FGDs that recruited participants across venues. FGD types were distributed evenly across geographic sites to ensure fair representation of venue/geographic-specific information. Additionally, two nonvenue FGD types were also conducted with street-based sex workers and on-call sex workers. The number and type of FGDs are summarized in .

Table 1. Number of focus group discussions by type of entertainment venues.

The project coordinator oversaw the implementation of the FGDs, as well as coordination of transcribers and translators.

At the beginning of the FGDs, the community lay health worker hung up topic cards around the room and gave the participants an opportunity to walk around and process the topics prior to beginning the FGD. The data collector read the informed consent to the participants and each participant was given a signed copy of the consent form. A FGD lasted about 90 min and covered a variety of topics including: STIs, HIV, modern contraception, gynecological health, condom use, cancer, pregnancy, violence, and substance use. Within each topical area, questions explored participants’ understanding of the topic area, known myths/misconceptions, practices related to the topic and ways in which health information and linkages could be disseminated to improve outcomes related to that issue. Women were encouraged to share experiences and stories to generate conversation.

After the FGD was completed, the data collector and peer data collector completed an FGD summary form together, which was then submitted to the project coordinator providing any contextual information and subjective information related to the FGDs that may be helpful in the analyses. All FGDs were audio recorded. Transcribers transcribed the data in Khmer. Translators then accessed the Khmer transcripts to translate into English for content analyses.

Due to the breadth of topics and time constraints, not all health topics were covered in all FGDs. Explicit questions related to substance use, including alcohol, were included in 12 of the 27 FGDs and split among venue types and geographic locations. While alcohol issues were discussed more frequently within the FGDs that explicitly raised questions around alcohol use, issues around substance use also came up freely in FGDs where those questions were not explicitly asked. In the FGDs not explicitly posing question on substance use, alcohol use was most often raised when the FGD moderator asked, “What is the most critical health issue that you and your peers face?” and women often talked about alcohol and related physical health issues (as discussed below in theme 3). Alcohol was also discussed in the context of violence, both in terms of alcohol use leading to higher risk of experiencing violence, and also when illustrating the general context of substance use among partners and clients with whom FEWs are frequently interacting (as discussed below in theme 5).

Data analyses

Qualitative data were analyzed first with in vivo coding and then secondary thematic coding using Dedoose (Dedoose qualitative coding software, Version 8.0.35, 2018). Two researchers independently labeled sections of transcripts that were associated with larger categories and subcategories based on the initial content analysis matrix, and created codes. Applying the Dedoose code application test using the four main themes, the pooled Cohen’s Kappa for inter-rate reliability between the two researchers across the four themes was 0.84, which falls into the “excellent agreement” category based on Miles and Huberman “Qualitative Data Analysis” textbook (1994). The researchers came together to discuss any disagreement in codes. Differences in code frequency across venue types and geographic locations were assessed. Large disparities in the appearance of codes in some venues or geographic locations as compared to others are presented in the results. This process of coding continued iteratively until a final codebook was created. The codebook was refined several times and from the final codebook, a diagram that summarized the conceptual relationships between the codes was created (conceptual model). The conceptual model was influenced by existing models from complimentary literature. The project coordinator was present at all FGDs and reviewed and helped to finalize the conceptual model presented below.

Ethical considerations

All key research and data collection personnel involved in this study completed the online the National Institute of Health (NIH) research ethics course on the protection of human research participants. All focus groups participants were informed of the study purpose and the risks and benefits to their voluntary participations. All participants completed a written informed consent. The study topics included personal information about extremely sensitive topics. We offered all participants escorted referrals to counselors and health services upon request and referral to a local women’s center for those who have experiences of violence. This study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (NECHR, No. 142NECHR) within the Ministry of Health in Cambodia and the Touro College Institutional Review Board (No. PH-0117).

Results

The seven main themes and sub-themes within each main theme are summarized in and presented in details with example quotes in the text below. The first four main themes related to alcohol decision-making by FEWs are summarized in , which presents a conceptual diagram to illustrate that these are not separate themes but points on a continuum (). This conceptual model was adapted from the “Continuum of Volition” model developed as an explanatory model to understand the reasons young women engage in cross-generational relationships (Weissman et al., Citation2006). The idea of a continuum was especially helpful in understanding the roles of alcohol use within the context of FEWs lives at work and in their personal lives.

Table 2. Themes, codes, definition and sample quotes related to alcohol use among FEWs.

Pressured or coerced alcohol use

Most FGD participants reported that the majority of alcohol use among FEWs occurred during work hours. Participants described many situations as forced drinking, to varying degrees. Among the different groups, two main sources of pressure were identified related to forced drinking, pressure from clients and pressure from supervisors.

Pressure to drink alcohol from clients

Direct external pressure either in the form of verbal or psychological coercion, or the threat of violence or actual violence from clients was noted as common ways FEWs reported experiencing being forced to drink excessive alcohol. Pressure from clients to drink alcohol was more often discussed in the FGDs among women working in beer gardens, and the FGD with parenting FEWs from across venues.

I was forced by clients to drink beer. Usually, clients force us to drink beer but never drugs. They force us to drink beer because they want happiness, so when we refuse, the clients will be sad. (Phnom Penh, karaoke)

When we say we can’t drink, the clients ask us to leave. Sometimes when we don’t drink, they (clients) slap us. If we don’t drink, we will be slapped. (Siem Reap, street-based sex work)

Even the clients force us to drink. If we don’t drink, they will keep staring at you. Our clients will make a note on us [to our boss]. If we don’t drink, they will tell the boss that we are of no use. (Battambang, parenting FEW)

And then they force us to drink alcohol. When we say we can’t drink, they will just say why we work as FEW if we can’t drink. (Siem Reap, beer garden)

By describing how men preferred them to drink or be drunk for that reason, participants highlighted the power and gender dynamics, which may lead to implicit pressure to drink.

Pressure to drink alcohol from supervisors

Another theme, although reported less frequently, was feeling forced or coerced to drink from managers or supervisors. This included supervisors telling women that they must drink because that is what they were hired to do, paying them to drink, and also threatening them with being fired. Pressure from supervisors to drink was equally raised across beer gardens, karaoke bars, and massage venues.

Sometimes not only the clients but the bosses and managers also force us. Our [supervisors] force us to drink alcohol. (Siem Reap, beer garden)

When we say we can’t drink, our (supervisors) will just ask us why we work as FEWs if we can’t drink. If we did not drink, we would be fired. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

If we don’t drink, [clients] will tell the boss or manager. I’m afraid of losing the job or getting scolded. (Siem Reap, beer garden)

Economically rational alcohol use

While FEWs reported feeling pressure to drink by clients, they also spoke about drinking in order to maintain their livelihoods or to increase their paycheck. Women expressed that drinking excessively to please clients and increase pay was common among FEWs.

Job requirement

Even though participants stated they had to drink in order to make more money, many did not interpret this as being forced into drinking. Many women stated that it was just part of the job and that when they signed up for the job, they knew drinking was a requirement. Women across venues talked about drinking alcohol as a duty or requirement, but more women raised this issue who worked in karaoke bars and beer gardens.

We simply use alcohol because we work at a karaoke bar; if we don’t drink, we won’t earn any money. karaoke bar is a place not only for singing but also for serving alcohol and entertaining with women. Boss hires us to drink with clients. (Battambang, karaoke)

I just think that if we don’t help drink, the boss won’t get revenue and we won’t get much salary since they have to pay for water bill and electricity. (Banteay Meanchey, karaoke)

Women talked about feeling shy until drinking alcohol, which helped them to perform their job better.

Economic survival

Women also described experiencing economic hardship, which constrains their ability to negotiate alcohol use – drinking for more money through tips was described as an economic survival strategy. Many women described drinking because they need money and not necessarily because they feel forced. Women repeatedly talked about receiving higher tips from clients, or higher monetary incentives from their employer for drinking. Increased pay as a motivation for alcohol use was cited more often in FGDs among women working in massage venues (explicit alcohol ask) and on-call FEWs (non-explicit alcohol ask).

Our money, our salary, it all comes with guests. If we don’t drink with guests, they will just tell our boss, then our salary will be reduced. So, we’re just going to drink as much as we can. (Phnom Penh, beer garden)

We have to drink since we don’t have any money. We are poor, and we need money, so we must drink for money. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

I want tips that’s why I drink… we must drink to earn income for brew company. If we did not drink, we would be fired. When we drank several hours and still not finish a case, we would be blamed. But if we spent like one hour, we would get rewarded…. Such as Angkor beer bottles or cans they pay us by the number of cans or bottles 500 or 1000 riels per can/bottle [USD$0.12 or $0.25 per can/bottle]. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

*Minimum wage in Cambodia in 2018 was $170/month. Based on a 40 hour work week, hourly wage is about $1.06.

A few women talked about drinking as a way to encourage clients to drink more, which can make them happier, calmer or pass out so they can leave.

I drink because some clients always sexually harass me so I drink with them and make them drunk, and then I can leave ASAP. (Banteay Meanchey, karaoke)

Socially rational alcohol use

Pressure to drink alcohol from peers

Pressure from peers to drink was also discussed among women in the FGDs, although with less frequency than clients and supervisors. They described how other women at their place of work would feel upset if one woman doesn't drink because it is expected from everyone, and all of their pay depends on it.

We must help drink from the big roundtable, because we get the same bill. If we don’t help drink, other women would be jealous. So we must drink. (Siem Reap, street-based sex worker)

For me, both supervisors and peers always force me to drink they don’t care about health because they are low educated. (Battambang, karaoke bar)

One participant who had been promoted to team leader described that because of her role, she has an easier time refraining from drinking because of her leadership role:

I pretend I am drinking. I am a team leader so I move from one table to another. It’s not hard for me to avoid drinking. (Banteay Meanchey, parenting FEW)

This statement also reflects the hierarchy within venues that influences ability to negotiate drinking. Women also expressed talking about wanting to drink alcohol to be more uninhibited or more fun at work.

Drinking in response to stress in life

Women also talked about choosing to drink beer to cope with daily life and the pressures and stress of their life.

We are not happy, we think a lot and we can’t help. So the beer helps us not to think a lot. (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

I only drink to forget my sadness. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

For alcohol, it just helps us loosen the mood down a bit. (Banteay Meanchey, karaoke)

Voluntary alcohol use

Drinking for enjoyment and fun

Women described drinking just to have fun or enjoy life. Even though many FEWs consume alcohol as part of their occupation, some women still mentioned relaxing with friends and family outside of work or during celebrations and drinking some beer. When women talked about drinking for enjoyment, they referred to drinking alcohol at home or outside of the work environment.

I drink at home when I am happy. (Siem Reap, street-based sex work)

I chip in with friends and drink at home. (Banteay Meanchey, karaoke)

[Alcohol] encourages us to tell jokes, to relieve the suffering, when there is reunion, we drink and we laugh. Whenever I drink with my family, all the worry will be gone. (Phnom Penh, karaoke)

Perceived impact of alcohol use

Physical health

Many of the participants described how they feel their drinking at work has affected their bodies. The most common physical response to drinking alcohol reported by women in the FGDs was vaginal discharge and gastrointestinal issues. Women also generally reported feeling weak and tired.

For me, I used to have [vaginal] discharge because I drank alcohol that is hot, and I drank not enough water. (Banteay Meanchey, parenting)

When we drink too much, we wake up with a weak body, with no strength. (Phnom Penh, beer garden)

When we drink everyday it leads to stomach pain. Alcohol use causes stomachache and irritation of gallbladder. (Phnom Penh, beer garden)

I used to vomit a lot and causing many diseases from drinking; we do not want to do it, but the clients force us to drink. (Battambang, on-call sex work)

Alcohol is very harmful for our health. It causes inflammation to our stomach, intestine, liver and urinary tract. It also causes inflammation of uterus. I think we share the same work we should love each other and help each other. We should not force each other like this. (Battambang, karaoke bar)

Gastrointestinal issues were referenced across venues, including among FGDs that did not explicitly ask about alcohol. Vaginal discharge issues were raised more often within the parenting FGDs, and the karaoke FGDs.

Mental health

Some women talked about excessive alcohol as a method for coping with the challenges of their life and their job. Some women also talked about the other side of such a strategy – drinking so much that they put themselves in more unsafe situations.

When we are not happy, we think a lot, and we can’t help it. So the beer helps us not to think a lot. (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

For me, after drinking I lose my consciousness. I don’t know where I am. I fall asleep and sometimes I forget whether I was paid or not. (Battambang, karaoke bar)

Drinking while on medication

Some women discussed what they do when they need to take an antibiotic, which is contraindicated with alcohol. Even if some women are supported by supervisors to take time off from work, pausing work results in a loss of income.

If we took medicines we could not drink. So, we could not earn money. If we did not drink, we would be fired in just one day not wait until seven days. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

The medicine was effective, but still I have to work and drink. The drinking contradicts the medicine. It’s difficult that we have to stop working if we want to take the medicine. (Banteay Meanchey, mixed)

If we take the medicine and drink, we may face health problems, even death, so we tell the boss to let us not drink. If the boss doesn’t forgive us or tolerate with us, we may just try to stop [drinking] temporarily. (Phnom Penh, beer garden)

I keep medicines at bay because I could not [not] drink for very long time. I need money. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

Economic cost of drinking

One thread of conversation in one FGD referenced women paying for services to reduce the impact of excessive alcohol on their bodies such as intravenous fluid as a hangover treatment. While this theme was not raised consistently across venues and geographies, it was relevant to highlight given the economic framing of alcohol use.

Sometimes I get hangover the next morning after drinking, and I have to spend money on treatment such as intravenous fluid injection. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

I spent money a lot on treatment such as medicines and intravenous fluid injection. I earned only $10 in tips but I spent on my treatment more than $10 - it can be $30 sometimes. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

If I drink a little bit, it won’t matter. But if I get drunk I will throw up and need coining therapy (scraping for wind). (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

Another aspect of the economic cost of drinking was that it may limit their ability to work in this field for very long.

For me, I think we can’t work for long time if we drink much every day, at most four to five years, we will get sick because of alcohol drinking. (Battambang, karaoke bar)

Strategies to manage the drinking environment

Avoiding alcohol

Women reported developing coping mechanisms to deal with excessive drinking at work. They described pretending to drink (pouring drinks under the table, adding a lot of ice, or drinking juice), and claiming to be sick.

I work at a karaoke bar. I put a two-liter plastic bottle under my table, and I pour some beer to that bottle before I cheer with my clients. (Phnom Penh, karaoke bar)

Sometimes if we do not want to drink, we pretend to vomit, and they would not force us anymore (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

We cheer while we were talking. So, I pretended like I am drinking, and I put down my glass. (Banteay Meanchey, parenting FEW)

Sometimes I tell them (the clients) I am sick. They allow me to drink fruit juice or water instead. (Banteay Meanchey, parenting FEW)

Some women talked about working together to help each other avoid or reduce alcohol intake.

I sometimes say I am drunk, so that I can have only a little more. It's important that we talk to them, sometimes our co-workers at the table together can help put ice, and help with the clients. (Battambang, parenting FEW)

A few women talked about not wanting to try too many tactics because of a fear of getting caught:

I don’t because I’m afraid we will get caught by the clients, and we will be blamed by the boss. (Banteay Meanchey, karaoke FGD)

Preparing for drinking

Women talked about things they do before work to prepare their bodies for excessive alcohol use, in particular eating rice or meat and drinking water.

We have to have lots of rice before drinking so that it also won’t damage our health (stomach and intestine as well). We also have lots of snacks during drinking. (Phnom Penh, sex worker)

Some women also talked about drinking energy drinks (like Red Bull) or taking stimulants while drinking to stay awake. One FGD participant mentioned that drinking energy drinks could be cost prohibitive as it is more expensive than alcohol.

We take some pills and energy drinks (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

I have seen some people using drugs outside to avoid getting drunk and not sleepy. (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

Failed tactics

Women described that their tactics do not always work completely and are illustrative of the pressure and coercion FEWs face from clients. Even when they tell the clients they are sick, they are still pressured to drink. The power dynamics between FEWs and clients, at least in these two cases, are clearly in favor of the clients.

Sometimes, I say that I am sick and cannot drink but my clients told me that if I was sick I should just drink a little. We cannot avoid drinking. (Battambang, beer garden)

I can negotiate with clients and tell them I have stomach ache. We still drink at least one can, but that is fewer than the previous day or in previous room that same night. (Phnom Penh, massage parlor)

Intersections of violence and alcohol use

Women also talked about the effects of alcohol on their interactions with clients and partners, often within the context of gender-based violence. For example, when clients are drunk it is harder to negotiate condom use, and they may sexually or physically assault FEWs.

Partner violence

When partners are drunk, they are more likely to be physically or sexually violent.

Since my house was next to the river (far away), there was no legal service or anything. My husband always hits me and hurts me physically and emotionally when he is drunk. (Battambang, on-call sex worker)

Client Violence

Women talked about personal experiences as well as stories from friend about clients were violent when drunk.

I used to see a client who was drunk at that time. He was talking a lot with women at my place. But I didn’t know what my friend said to him that made him angry with her. He was hitting my friend by a glass of beer.

M: Was he drunk?

R6: Yes (Battambang, karaoke bar)

When they are drunk, they lose control, or when we make a mistake, they break the glass, or throw the glass on us. (Phnom Penh, karaoke FGD)

Among the FGDs, women more often talked about experiences in alcohol-related violence from clients in beer gardens as compared to other venues. Women in the freelance sex worker FGDs more often cited experiences of alcohol-related partner violence as compared to other FGDs.

Condom use and alcohol

Women in the FGDs also talked about the challenges in negotiating condom use with partners and clients when the clients/partners are drunk.

Sometimes women working at the club want to drink and they become forgetful (some may not) (Battambang, massage parlor)

When they’re drunk, they don’t want to use condoms, and they shouted at us with threatening words. That’s what my friends told me. (Siem Reap, beer garden)

While the women did not talk about their challenges in condom negotiation if they themselves are drunk, it is important to understand the wider context of alcohol in which many women live, and that she may face unsafe and harmful situations as part of her work and daily life regardless of her use of alcohol.

Discussion

The women who participated in the FGDs, highlighted the impact, oppression and their own autonomy related to alcohol use in entertainment venues and in sex work. These themes were organized into the conceptual diagram represented above to highlight the complexity of force and autonomy related to alcohol use for FEWs in Cambodia. Themes within this conceptual model are supported by studies of FEWs in Cambodia, China and Indonesia where participants reported risky drinking at work (Chen et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Couture et al., Citation2016; Safika et al., Citation2011; Zaller et al., Citation2014). Women who participated in the FGDs reported experiencing both external pressure to drink excess alcohol from clients, supervisors, peers and internal pressures to keep their jobs and to make more money through tips. Pressure on FEWs to drink from clients and supervisors was documented in two other studies in Cambodia (Couture et al., Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2016). This paper contributes to this literature by elaborating the factors underlying alcohol use to inform design of interventions for FEWs.

FGD participants were aware that their alcohol use may have both distal and proximal health effects. They were concerned about the impacts of their alcohol intake on their physical and mental health, impacts that have been demonstrated in the literature as well (Li et al., Citation2010). One important physical health impact that women talked about that has not been well documented in the literature is vaginal discharge. This was a theme that emerged from almost every discussion group and is an issue about which the women requested more information. There is also a larger context of hotness and coldness related to Eastern Medicine, which impacts bodily functions, including vaginal discharge. Alcohol generates internal heat, which leads to discharge. Additionally, the relationship between alcohol and discharge may also be important because vaginal discharge can be a symptom of bacterial STIs or other infections. If women attribute alcohol as the cause of the discharge, they may be less likely to seek testing and treatment. Also, for women such as FEWs who are at a higher risk of bacterial STIs, but whose livelihood is dependent on alcohol use, adhering to a recommended antibiotic regimen may be particularly challenging and potentially contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Women in this study discussed having developed strategies to avoid drinking at work or to protect their bodies from the impact of the alcohol. In this way, even women with minimal power, they are exerting power and autonomy in small ways over clients and supervisors. We did not find any other academic documentation of these strategies among FEWs, though strategies are certainly shared across FEW networks, friends and peers.

Women talked about the larger context of gender-based violence around them in relation to alcohol use in venues, and inconsistent protection from supervisors from drunk clients. Ultimately, the entertainment venue business is built on purchasing alcohol, so preventing intoxication among clients is not in the best interest of the venue. Women in various roles from waitress or hostess at a beer garden to a karaoke bar entertainer, are all in risky and potentially dangerous work environments due to heavy client drinking. Women also talked about using stimulants in addition to alcohol. Related research suggests that amphetamine-type stimulant use among FEWs in Cambodia is used to increase their ability to meet the physiological demands of their work (Dixon et al., Citation2015), used to manage depression related to economic and social problems (Coupland et al., Citation2018) and is associated with unprotected sex and STIs (Couture et al., Citation2011). Women also talked about facing alcohol-related partner violence at home, which may be more prevalent among FEWs due to male partners’ feelings of emasculation due to their female partner’s work (Panchanadeswara et al., Citation2009) and also could contribute to women using alcohol and other substances as a coping mechanism.

Women did not discuss the ways in which alcohol use inhibited their ability to negotiate condom use with clients. However, they did discuss how client/partner alcohol use made it more challenging for them to negotiate condom use overall, regardless of their (the FEW’s) alcohol use. Past research in Cambodia found that the average amount of alcohol consumed per day was significantly higher among respondents who reported inconsistent condom use. But because it was a cross-sectional study, the temporal relationship between alcohol use and condom use is not clear (Yi et al., Citation2017). Other studies have demonstrated the link between alcohol use and condom use (Chersich et al., Citation2007) or have found inconclusive evidence of this link (Li et al., Citation2010).

Limitations

Some important limitations impact the interpretation of our results. First, in order to capture a wide variety of opinions and to generate rich dialogue, we utilized the FGD methodology. However, we recognize that for issues such as substance use, speaking in a group that is confidential but not anonymous may inhibit disclosure of personal information. Second, participants were selected using purposive sampling and so this data may not produce findings that are generalizable to the entire population of FEWs. Third, we limited participation to those FEWs under 30 years of age. As a result, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to the entire population of FEWs. Lastly, the intention behind conducting FGDs was not to explore substance use alone, but rather to seek information to inform a larger mobile health program. Therefore, there were likely conversation threads related to substance use that could have been explored further, and richer information could have been gathered, had this exploration focused solely on substance use.

Conclusions

Past studies on FEWs and alcohol use have recommended that FEWs would benefit from interventions that encourage the reduction of alcohol use (Chen et al., Citation2015; Chen, Citation2018; Chiao et al., Citation2006; Couture et al., Citation2011; Safika et al., Citation2011) or that education of managers and supervisors would lead to a reduction in pressure to drink alcohol (Hsu et al., Citation2016). Our studies find that drinking is closely linked to woman’s livelihoods and therefore, reducing drinking may have a direct, negative effect on their economic well-being. The findings in this paper indicate that traditional alcohol use behavior change program directed at the person with the least amount of power (i.e. FEWs) and the least economic incentive to change, will likely be ineffective. This suggests that structural changes are needed in the workplace environment to support healthy work environments for FEWs. In some countries, larger structural changes such as partially legalizing and regulating sex work following such frameworks as “the Nordic Model” has shown some benefits to the health of sex workers without criminalization (Skilbrei & Holmstrom, Citation2017). Creating laws, with effective monitoring and enforcement, that respond to the health and safety risks faced by FEWs may allow for the provision of certain protections such as venue-based policies allowing FEWs to decline drinking without recourse or to eliminate economic incentives for drinking, as well as regular health care or legal aid in the case of sexual violence.

One concrete recommendation for this context is to pursue action-oriented community-level responses in conjunction with supervisors, managers and owners to address the issue. Anecdotally, there are stories of “champion” supervisors, who do take the health of their workers seriously, and can be part of supporting a broader solution. If women know they can receive comparable pay in venues which support worker’s health, they may naturally shift the response of venues through employment choice. Currently, however, because most venues either do not support women’s refusal of alcohol, or turn a blind eye to coercion, women are left without another employment option. Despite the challenges of creating the best policy, this study underscores the importance of structural-level changes over individual-level programs in supporting the health and safety of FEWs in Cambodia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Brody, C., Tuot, S., Chhoun, P., Swendenman, D., Kaplan, K. C., & Yi, S. (2018). Mobile Link – A theory-based messaging intervention for improving sexual and reproductive health of female entertainment workers in Cambodia: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 19(1), 235. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-3090-9

- Cambodian textile workers killed during pay protest. (2014). British Broadcasting Company. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-asia-25593553/cambodian-textile-workers-killed-during-pay-protest.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Fact sheets: Alcohol use and your health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

- Chiao, C., Morisky, D. E., Rosenberg, R., Ksobiech, K., & Malow, R. (2006). The relationship between HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infection risk and alcohol use during commercial sex episodes: Results from the study of female commercial sex workers in the Philippines. Substance Use and Misuse, 41(10-12), 1509–1533.

- Chen, Y., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Zhang, C., Wen, X., & Guo, W. (2012). Alcohol consumption in relation to work environment and key sociodemographic characteristics among female sex workers in China. Substance Use and Misuse, 47(10), 1086–1099. doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.678540

- Chen, Y., Li, X., Shen, Z., Zhou, Y., & Tang, Z. (2015). Drinking reasons and alcohol problems by work venue among female sex workers in Guangxi, China. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(5), 642–652. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.997827

- Chersich, M. F., Luchters, S. M. F., Malonza, I. M., Mwarogo, P., King'ola, N., & Temmerman, M. (2007). Heavy episodic drinking among Kenyan female sex workers is associated with unsafe sex, sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 18(11), 764–769.

- Coupland, H., Page, K., Stein, E., Carrico, A., Evans, J., Dixon, T., … Maher, L. (2018). Structural interventions and social suffering: Responding to amphetamine-type stimulant use among female entertainment and sex workers in Cambodia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2018(64), 70–78. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.12.002

- Couture, M. C., Page, K., Sansothy, N., Stein, E., Vun, M. C., & Hahn, J. A. (2016). High prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use and comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption to phosphatidylethanol among women engaged in sex work and their male clients in Cambodia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.011

- Couture, M.-C., Sansothy, N., Sapphon, V., Phal, S., Sichan, K., Stein, E., … Page, K. (2011). Young women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, have high incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and amphetamine-type stimulant use: New challenges to HIV prevention and risk. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38(1), 33–39. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182000e47

- Dedoose Version 8.0.35. (2018). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Retrieved from www.dedoose.com.

- Dixon, T. C., Ngak, S., Stein, E., Carrico, A., Page, K., & Maher, L. (2015). Pharmacology, physiology and performance: Occupational drug use and HIV risk among female entertainment and sex workers in Cambodia. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(1), 33. doi:10.1186/s12954-015-0068-8

- Hsu, L., Howard, R., Torriente, A., & Por, C. (2016). Promoting occupational safety and health for Cambodian entertainment sector workers. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 26, 301–313. doi:10.1177/1048291116652688

- Human Rights Watch. (2015). Cambodia labor laws fail protect garment workers. November 3, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/03/11/cambodia-labor-laws-fail-protect-garment-workers.

- Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Kaufman, M., Cain, D., & Jooste, S. (2007). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science, 8(2), 141–151. doi:10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2

- KHANA. (2017). Annual report: United for a stronger community. Phnom Penh: KHANA. Retrieved from, https://www.khana.org.kh.

- Kumar, M. S. (2003). A rapid situational assessment of sexual risk behavior and substance use in sex workers and clients of sex workers in Chennai (Madras), south India. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70797.

- Li, Q., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2010). Alcohol use among female sex workers and male clients: An integrative review of global literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 45(2), 188–199. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp095

- Maher, L., Mooney-Somers, J., Phlong, P., Couture, M.-C., Stein, E., Evans, J., … Page, K. (2011). Selling sex in unsafe spaces: Sex work risk environments in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Harm Reduction Journal, 8(1), 30. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-8-30

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Mun, P., Tuot, S., Heng, S., Chhim, S., Lienemann, M., Choun, P., … Yi, S. (2017). National integrated biological and behavioral survey among female entertainment workers in Cambodia, 2016. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: KHANA, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STD (NCHADS).

- Panchanadeswara, S., Sethulakshmi, C. J., Sivaram, S., Srikrishnan, A. K., Latkin, C., Bentley Me…Celentano, D. (2009). Intimate partner violence is as important as client violence in increasing street-based female sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV in India. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19, 106–112. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.013

- Rojanapithayakorn, W., & Phalla, T. (2000). STI/HIV. 100% condom use programme in entertainment establishments. World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved from http://www.hivpolicy.org/Library/HPP000180.pdf.

- Safika, I., Johnson, T., & Levy, J. (2011). A venue analysis of alcohol use prior to sexual intercourse among female sex workers in Senggigi, Indonesia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 22(1), 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.09.003

- Shuper, P. A., Neuman, M., Kanteres, F., Ballunas, D., Joharchi, N., & Rehm, J. (2010). Causal consideration on alcohol and HIV/AIDS—A systematic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 45(2), 156–166.

- Skilbrei, M. L., & Holmstrom, C. (2017). Linking prostitution and human trafficking policies: The Nordic experience. In: Nelen H., Siegel D. (Eds) Contemporary organized crime. Studies of organized crime, (vol 16). SpringerLink.

- Weissman, A., Cocker, J., Sherburne, L., Powers, M. B., Loich, R., & Mukaka, M. (2006). Cross-generational relationships: Using a ‘Continuum of Volition’ in HIV prevention work among young people. Gender and Development, 14(1), 81–94.

- Wong, M. L., Teo, A. K. J., Tai, B. C., Ng, A. M. T., Lim, R. B. T., Tham, D. K. T., … Lubek, I. (2018). Trends in unprotected interocurse among heterosexual men before and after brothel ban in Siem Reap, Cambodia: A serial cross-sectional study (2003-2012). BMC Public Health, 18(1), 411. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5321-0

- Yang, C., Latkin, C., Luan, R., & Nelson, K. (2013). Factors associated with drinking alcohol before visiting female sex workers among men in Sichuan Province, China. IDS and Behavaior, 17(2), 568–573. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0260-8

- Yi, S., Tuot, S., Chhoun, P., Pal, K., Ngin, C., Chhim, K., & Brody, C. (2017). Sex with sweethearts: Exploring factors associated with inconsistent condom use among unmarried female entertainment workers in Cambodia. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 20.

- Zaller, N., Huang, W., He, H., Dong, Y., Song, D., Zhang, H., & Operario, D. (2014). Risky alcohol use among migrant women in entertainment venues in China. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 49(3), 321–326. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agt184