Abstract

Background

Nightclubs and bars are recreational settings with extensive availability and consumption of alcohol and recreational drugs.

Objectives

This study aims to determine the proportion of nightclub patrons in Norway that tested positive for illicit drugs, moreover, we examined the correlation between positive test results and demographic and substance use characteristics.

Methods

Patrons were recruited outside nightclubs on Friday and Saturday nights between 10:00 pm and 04:00 am. Substance use was determined by breath testing and oral fluid testing for alcohol and drugs, respectively, using accurate and specific analytical methods. Questionnaires recorded demographic and substance use characteristics.

Results

Of the 1988 included nightclub patrons, 90% tested positive for alcohol, 14% for illicit drug use, and 3% for two or more illicit drugs. The proportion of patrons who tested positive for illicit drugs was highest in the early hours of the morning. Nine out of ten who tested positive for illicit drugs also consumed alcohol. Testing positive for one or more illicit drugs was most strongly correlated with being male and unemployed, using tobacco or other nicotine products, and early on-set illicit drug use; further the correlations were strongest among those who tested positive for two or more illicit drugs.

Conclusions/Importance: Patrons who used illicit drugs before or during nightclub visits most often combined drug use with alcohol consumption. Substituting alcohol with cannabis or other drugs was not common in this cohort. The study results provide evidence to introduce harm-reduction prevention programs to address illicit drug and excessive alcohol consumption.

Introduction

Nightclubs and bars are recreational settings with extensive consumption of alcohol, and where recreational drugs are available and used, often in addition to alcohol (Bellis et al., Citation2003; European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction [EMCDDA], Citation2015). Patrons may also be introduced to drug use in connection with nightclub visits (Bellis et al., Citation2003; O’Hagan & Smith, Citation2017; Van Havere et al., Citation2009). Nightclubs witness excessive alcohol and drug consumption because they act as spaces for “time-out” behavior, thereby reducing social control and individual accountability, and allowing effortless social interaction with peers due to reduced inhibitions (Cavan, Citation1966; Comasco et al., Citation2010; Gahlinger, Citation2004; Listiak, Citation1974).

Using alcohol or psychoactive drugs increases the risk of well-known adverse effects. Acute intoxication may elevate the likelihood of violence, injuries, risky sexual behavior and aberrant driving. Moreover, long-term use may cause somatic and psychiatric illnesses, reduced productivity, and cessation of educational or employment activities. Subsequently, acute intoxication increases the risk of substance addiction (Arnett, Citation2000; Bachman et al., Citation1997; Calafat et al., Citation2011; Degenhardt & Hall, Citation2012; Duff, Citation2008; Schulte & Hser, Citation2013). The use of multiple substances may further cause risk-taking behavior, while it also increases the probability of health and social problems, psychological distress, and even overdose or death, particularly when used simultaneously (Baggio et al., Citation2014; Connor et al., Citation2014; Crummy et al., Citation2020; Martin, Citation2008; Subbaraman & Kerr, Citation2015). As both experimental and regular drug users tend to underestimate the risks associated with drug use, they often use multiple rather than single substances to enhance psychoactive effects or alleviate negative side-effects, such as drug craving or withdrawal (Chomynova et al., Citation2009; Connor et al., Citation2014).

Strict alcohol and drug regulations, including relatively high age limits for the purchase of alcohol, high prices, limitations of the availability, and fines or imprisonment penalties for illicit drug use, have been implemented in Norway (Ministry of Health and Care Services [MHCS], 2005). Moreover, venues serving alcohol may have their liquor license revoked if they are caught admitting or serving under-aged persons or patrons intoxicated by alcohol or drugs. It is illegal to buy, possess, use or sell illegal drugs, including cannabis.

The use of illicit drugs in Norway is at the European median or somewhat higher. In 2017, the self- reported illicit drug use in the past year among adults aged 15-64 years was 5.3% for cannabis, 1.1% for cocaine, 1.0% for 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), and 0.6% for amphetamines (EMCDDA, Citation2019b). In 2017, the self-reported illicit drug use in the U.S. among those aged 12 years or older was 15.0%, 2.2%, 0.9%, 0.6% for cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, and methamphetamine, respectively (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], Citation2019). Thus, the use of cannabis and cocaine in Norway was less common than in the U.S.

The most commonly used nightlife drugs are MDMA (ecstasy), cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, ketamine, and gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) (Degenhardt et al., Citation2005; EMCDDA, Citation2015; Gahlinger, Citation2004; Miller et al., Citation2009). Prior studies have shown that the aforementioned drugs are more commonly used by visitors of electronic dance music clubs and nightclubs than by bar and pub guests (Miller et al., Citation2015; Van Havere et al., Citation2011).

Polydrug use is popular among club goers, and MDMA and cocaine are commonly used in combination with other drugs (Grov et al., Citation2009; Winstock et al., Citation2001). An increase in nonmedical use of prescription drugs, such as benzodiazepines and opioids, has been reported in nightclubs (Kelly & Parsons, Citation2007; Kurtz et al., Citation2011), thereby increasing the risk of intoxication and overdoses. Nightlife attendees may be high-risk users and are a suitable target group for preventive measures (Akbar et al., Citation2011).

The majority of patrons arrive at nightclubs along with their peers (Miller et al., Citation2015), which can affect individual behavior through social comparison and social identity processes (Festinger, Citation1954; Hogg, Citation2013). Additionally, normative group patterns of alcohol and drug use are established through social modeling that occurs within the group (Miller et al., Citation2013a).

Most studies on illicit drug use, aimed at the general population or at individuals in high-risk settings, have focused on the self-reported consumption of separate drugs within defined time windows, such as weeks or months. It is important to note that self-reported data may be inaccurate. Recall bias and socially desirable responses (Johnson & Richter, Citation2004; Johnson & Fendrich, Citation2005) may lead to over- or under-reporting of actual drug consumption. Furthermore, not every drug user knows exactly what he/she has consumed (Tanner-Smith, Citation2006; Vogels et al., Citation2009). The problem may apply in particular to inexperienced users, but even experienced users do not always know the true content of the substances used. This problem may have increased in recent years as several new psychoactive substances (NPS) have appeared in the drug market. Nevertheless, the analysis of drugs in biological samples (e.g. blood, sweat, urine, or saliva) can objectively and correctly measure recent drug use.

This study examined questionnaire data, test results for drugs concentrations in oral fluid samples and blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) measured using a breathalyzer from a large sample of nightlife attendees. We aimed to determine the prevalence of single and multiple illicit drug use, and to study the correlation between positive test results and demographic and substance use characteristics.

Methods

Setting and study design

Data were collected in 2017 outside licensed nightclubs in the Norwegian capital Oslo (population 680,000) and in six small neighboring cities (population 20,000-80,000) within a 2 h drive from Oslo. All included nightclubs were popular dance music venues; however, none of them could be characterized as “rave clubs”. In Oslo, nightclubs were selected to represent a geographical spread within the inner city with different profiles and patron characteristics. The procedure for selecting clubs and recruitment of patrons has been published previously (Nordfjaern et al., Citation2016).

Data collection was performed from 10:00 pm to 04:00 am on Friday and Saturday nights between June and August 2017. Patron recruitment was performed outside the nightclubs. The research team established a “research station” outside the premises and approached the patrons during entry or exit. Patrons were informed about the study, which was voluntary and anonymous. Each patron who agreed to participate in the study was separately attended to by a research assistant to minimize response bias due to social desirability. On account of the non-feasibility of recruiting patrons using random sampling the study cohort may be regarded as a convenience sample. A voucher for free food was used as incentive for participation.

Questionnaire

After providing informed consent, participants were asked to complete a written questionnaire with questions on age, sex, level of education, working status, and whether the participant and her/his parents were born in Norway or abroad. They were requested to report the use of alcohol (and alcohol-intoxication), amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, NPS, and other illicit drugs in the last 48 h, last 30 days, and in the past 12 months. Moreover, age of first use, and age of first alcohol-intoxication were also recoded. Patrons were also requested to report tobacco smoking, use of E-cigarettes, and use of snus (Swedish snuff; tobacco that is placed under the lip) during the last 30 days. For the multinomial regression analyses, all answers were transformed into binary variables (see ). The questionnaire was labeled with the same unique barcode as the oral fluid collection tubes.

Table 1. Prevalence of demographic and substance use characteristics among nightclub patrons who tested positive for none, THC, stimulants, or multiple illicit drugs in oral fluid, and multinomial regression analysis with no detected illicit drug as reference presented as adjusted relative risk ratios (aRRR).

Breath alcohol testing

Breath alcohol content was determined using a Lion AlcolmeterTM 500 (Lion Laboratories Limited, Vale of Glamorgan, UK); the BAC was calculated based on the breath alcohol content. All patrons were instructed to drink a glass of water prior to the breath alcohol testing. A BAC of 0.010% or higher was regarded as a positive alcohol test, and a BAC of 0.10% or higher was defined as high BAC, which indicates binge drinking.

Oral fluid collection and drug testing

Samples of oral fluid (saliva) were collected using the Quantisal™ Oral Fluid Collection Device (Immunalysis Corporation, Pomona, CA, USA). The collection pad was placed between the tongue and cheek or under the tongue until the indicator turned blue, or until five minutes had passed; the collection pad was then transferred to a collector tube containing a preservative buffer solution. The tubes were placed in a cooling bag at a temperature of approximately 5 °C. The samples were transported to a laboratory in Oslo and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Samples were analyzed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (Valen et al., Citation2017), which is a highly specific methodology used to analyze targeted substances. In total, 29 illicit drugs and 20 psychoactive medicinal drugs or metabolites were tested for (see ). The cutoff concentrations defining positive drug tests were set sufficiently low to detect drug use prior to and during nightclub visits.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® Statistics version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used to compare proportions. Multinomial regression analysis was performed to compare the substance-use groups with the reference group; adjusted relative risk ratios (aRRR) were calculated together with 95% confidence intervals, and the Wald test was used to compare aRRRs.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (approval no. 2016/337).

Results

Sixteen nightclubs were included in this study; seven in Oslo and nine in smaller cities. Five were dance clubs with a focus on techno, house music, and similar music styles, whereas the others mostly played popular music. In total, 2005 nightclub patrons agreed to participate in the study. Of those, 17 patrons were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires or missing oral fluid samples. Thus, 1988 patrons were included in the final analysis. Demographic and substance use characteristics of the patrons are presented in . Almost two-thirds were male, over half were below age 26 years, and approximately half had completed higher education (bachelor’s degree or higher). Approximately half of the study sample were full-time employees, and more than one-quarter were students. Very few patrons were either unemployed or homemakers. While one out of seven patrons were immigrant, one out of four had immigrant parents.

Table 2. Sample demographic and substance use characteristics (n = 1988).

Almost half of the patrons reported that they had consumed alcohol until they felt alcohol-intoxicated at least once a week during the last month. Almost half of the patrons also reported that they were alcohol-intoxicated prior to age 16.

About one-third reported illicit drug use during the past 12 months, one fifth within the last 30 days, and one-tenth within the last 48 h. Cannabis use was the most frequently reported, followed by cocaine, MDMA and amphetamines, whereas very few reported the use of NPS or other illicit substances. Approximately 11% of the patrons reported illicit drug use prior to age 16.

The majority of patrons used tobacco or other nicotine products. Daily use of snus was more common than daily tobacco smoking; however, the proportion of patrons who reported daily or occasional smoking was approximately 50%, which was the same as the proportion of patrons who reported daily or occasional use of snus.

Breath alcohol testing revealed that approximately 90% tested positive for alcohol use (BAC ≥ 0.01%) and almost half of the patrons had a BAC of 0.10% or more (). Drug testing revealed the presence of illicit drugs in oral fluid samples (in concentrations above the cutoff) from approximately 14% of the patrons; about 3% tested positive for two or more illicit substances. The most commonly detected substance was tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), followed by cocaine, MDMA and amphetamines. Details on the drug findings are presented in . Drug testing also revealed that 1.4% of the patrons tested positive for medicinal drugs, mostly for sedatives and sleeping agents.

Table 3. Analytical test results for alcohol and drugs (n = 1988).

In total, 27.2% of the patrons in Oslo and 14.4% of those in other cities reported use of illicit drugs during the last 30 days (p < 0.005). Differences were found between the proportions of patrons that tested positive for illicit drugs in oral fluid samples in Oslo (17.7%) and those from other smaller cities (11.0%) (p < 0.005).

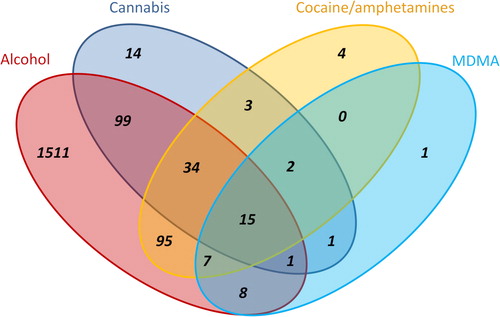

Approximately 8% of the total sample tested negative for both alcohol and illicit drugs. Among those who tested positive for illicit drugs, nine out of ten also tested positive for alcohol. Among those who tested negative for alcohol, one out of ten tested positive for one or more illicit drugs. The combinations of illicit drugs and alcohol are shown in . Amphetamines (amphetamine and methamphetamine) and cocaine were combined into one stimulant group to simplify the visual presentation. Seven patrons tested positive for illicit drugs other than those presented in ; four tested positive for dimethyltryptamine (DMT), one for ketamine and para-methoxymethamphetamine (PMMA), one for ketamine and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine (2 C-B), and one for methylphenidate and ethylphenidate. These drugs were used in combination with alcohol, THC or cocaine.

Figure 1. Number of positive oral fluid illicit drug tests and breath alcohol tests among 1988 nightlife patrons. Additional findings of medicinal drugs, NPS, and other rarely detected substances are not shown.

Medicinal drugs well-known for misuse, including alprazolam and clonazepam, were detected in four cases in total, all of them were used in combination with two or more of the illicit drugs presented in . Traces of other medicinal drugs found were most likely due to their therapeutic use.

The consumption of alcohol differed between cannabis and cocaine users. The proportion of patrons with BAC ≥0.10% was 44.6% (n = 50) among those who tested positive for THC and negative for other illicit drugs (n = 112), and 67.4% (n = 62) among those who tested positive for cocaine and negative for other illicit drugs (n = 92) (p < 0.01).

When grouping the patrons in relation to the time of inclusion (10:00-11:59 pm, 12:00-01:59 am, and 02:00-04:05 am), the proportion of males was higher after 12:00 am (midnight), as was the proportion of patrons with BAC ≥0.10%, and the proportion of patrons who reported drinking until intoxication on a weekly basis (). The proportion of patrons who tested positive for illicit drugs increased through the night, with the highest prevalence found among those included in the study after 02:00 am.

Table 4. Some demographic characteristics and drug findings among patrons in relation to time of the night.

In total, 220 patrons tested positive for only one illicit drug, mainly THC (n = 112), and cocaine (n = 92), and a few tested positive only for MDMA (n = 9), amphetamines (n = 5), or DMT (n = 2). Sixty-six patrons tested positive for two or more illicit drugs, most often cannabis combined with stimulants (n = 54). Demographic and substance use characteristics of nightclub patrons who tested positive for no illicit drug, only for cannabis, for one illicit stimulant drug (cocaine, amphetamine/methamphetamine, or MDMA), or for multiple illicit drugs (disregarding alcohol and medicinal drugs) are presented on the left-hand side of . The proportions of several covariates were higher among those who tested positive for one illicit substance compared to those who did not test positive for any illicit substance (the reference group), but highest among those who tested positive for two or more illicit drugs. This included the proportion of males, illicit drug use before age 16, and use of nicotine products. Among those who tested positive for only cannabis, or for two or more substances, the proportion of patrons who were unemployed were higher compared to those who tested negative for drugs, and the proportions with higher education were lower. Among those who tested positive for one stimulant drug, or multiple drugs, the proportion of patrons recruited in Oslo was higher, and the proportion reporting early-onset alcohol-intoxication was higher.

The results of the multinomial analysis, using those who tested negative for all illicit drugs as reference category, are presented on the right-hand side in and confirm the differences presented above. Being male, unemployed, without higher education, recruited in Oslo, using nicotine products, and reporting early-onset use of illicit drugs were significantly associated with testing positive for one or multiple illicit drugs. In addition, being 26 years or older and being alcohol-intoxicated prior to age 16 were associated with testing positive for multiple illicit drugs. The associations were highest for being male, unemployed, using nicotine products, and early-onset illicit drug use.

We further investigated the four parameters that were most strongly correlated with testing positive for illicit drugs (data not shown in tables). Among male patrons (n = 1232), 19.2% tested positive for one or more illicit drugs, and 4.8% tested positive for two or more. Among patrons who reported illicit drug use prior to age 16 (n = 213), 35.2% tested positive for one or more illicit drugs, and 12.7% tested positive for two or more illicit drugs. Further, among patrons who reported being unemployed (n = 46), 35.7% and 12.5% tested positive for one or more illicit drugs, and for two or more drugs, respectively. Among those who used tobacco or other nicotine products (n = 1248), 19.8% tested positive for one or more illicit drugs, and 4.7% tested positive for two or more illicit drugs. Thus, these correlates of illicit drug use had poor accuracy as predictors in distinguishing between illicit drug user and non-user, or multiple drug users and non-user.

Discussion

The key findings of this study were that approximately 14% of nightclub patrons tested positive for illicit drugs, mainly cannabis and cocaine, and more than 90% of those patrons also tested positive for alcohol, similar to the proportion among patrons who tested negative for illicit drugs. Approximately 3% tested positive for two or more illicit substances, and most of them used it in addition to alcohol. A clear under-reporting of cocaine use was found when comparing drug findings in oral fluid samples with self-reported drug use during the past 48 h. This result was also found in our previous study on music festival participants (Gjerde et al., Citation2019). Thus, in this context the analysis of oral fluid samples is likely to reflect recent drug use more accurately than self-reports.

The strongest correlates of testing positive for one of more illicit drugs were being male, using nicotine products, being unemployed, and early-onset illicit drug use. The identified correlates of illicit drug use cannot be used to identify users of one or more illicit drugs in a nightclub setting as the positive predictive values were 35% or lower for illicit drug use and 13% or lower for simultaneous use of two or more illicit drugs.

Most nightclub patrons arrive with the intention of consuming one or more alcoholic drinks; therefore, the proportion of patrons testing positive for alcohol was very high. The proportion of patrons with high BAC (≥0.10%) increased through the night as a result of continuous alcohol intake. Moreover, the proportion of patrons who tested positive for illicit drugs was highest after midnight, and the largest increase over time was observed for cocaine. Some patrons may have started drinking prior to arriving at the nightclub, sometimes called “pre-loading” (Foster & Ferguson, Citation2014), which may happen at a vorspiel party in a private residence, or in parks and other public spaces. As some patrons consume illicit drugs before entering nightclubs, to avoid being caught with illicit drugs on the premises, or to avoid spending time at the club waiting for the drugs to come into effect, detection of alcohol or drugs does not always indicate that these substances were consumed at the nightclub (Van Havere et al., Citation2009).

As expected, the proportion of patrons who reported illicit drug use during the past 12 months was much higher than the average for the Norwegian population (EMCDDA, Citation2018). For cannabis, the proportion was about seven times higher, while for other drugs it was 10-20 times higher.

A study examining substance use among patrons attending a 40-hour electronic music dance event on a cruise ship departing from Sweden showed high levels of alcohol use, and 10% tested positive for illicit drugs (amphetamines, MDMA, cannabis and cocaine) in oral fluid samples (Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012), which was similar to the findings of our study.

A previous Norwegian study that analyzed oral fluid samples from 1085 nightclub patrons in Oslo in 2014 found a somewhat higher prevalence of drugs than observed in our study (Bretteville-Jensen et al., Citation2019). The use of a more sensitive analytical method and patrons only from Oslo could have been the reasons for this difference.

The prevalence of illicit drug use was found to be higher among nightclub patrons in Oslo than in nearby smaller cities, which may be due to the greater availability of party drugs in Oslo. In addition, a recent study on illicit drug use among Norwegian university and college students found that a larger proportion of students from Oslo reported illicit drug use compared with those from other Norwegian cities (Heradstveit et al., Citation2020).

Results from studies in Australia and the USA show large differences from our findings (Johnson et al., Citation2009; Miller et al., Citation2013b; Miller et al., Citation2015; Voas et al., Citation2006). These differences may be related to disparities in laws, enforcement, public attitudes toward illicit drug use, as well as the availability and popularity of different types of illicit drugs. However, these differences could also reflect the types of nightclubs included in the studies. In our study, only five out of 16 nightclubs were dance clubs with a focus on techno, house music, and similar music styles. The use of party drugs such as MDMA and cocaine is expected to be more common in such venues, which may explain the present study’s lower prevalence of illicit drug use compared with other studies.

The use of illicit drugs and substance use problems may be associated with several factors, including gender, age, socio-economic and demographic characteristics, personality traits, personality disorders, mental health, genetic factors, conformity with peers, and early initiation into alcohol and nicotine use (Berge, Citation2015; Henneberger et al., Citation2021; Kashdan et al., Citation2005; Meyers & Dick, Citation2010; Sussman et al., Citation2008; von Sydow et al., Citation2002). Although we did not record if patrons arrived/exited the nightclubs alone or in groups, it is reasonable to believe that most patrons arrived in groups with peers, as also suggested by Miller et al. (Citation2015), which can modulate alcohol and drug use (Miller et al., Citation2013a).

Studies have found that substance use during early adolescence was associated with lower academic achievements and employment problems (Ellickson et al., Citation2003; Fergusson & Boden, Citation2008). However, as lower school performance may also lead to substance use, one must be cautious while claiming a causal relationship (Hayatbakhsh et al., Citation2011; Latvala et al., Citation2014). Our study found a significant association between illicit drug use and being male, unemployed, lacking higher education, early-onset illicit drug use, and use of tobacco or other nicotine products. Testing positive for two or more illicit drugs was also associated with being alcohol-intoxicated prior to age 16, indicating that early age initiation of substance use was strongly correlated with polydrug use, which was most common among older patrons.

While studies have found that some people substituted the use of alcohol with cannabis or other drugs, we found that a vast majority of those who tested positive for drugs also had alcohol in their system. Moreover, most of the patrons who tested negative for alcohol also tested negative for drugs, thereby indicating that they did not replace the use of alcohol with drugs. However, we found that having a high BAC was less common among those who tested positive for cannabis at nightclubs than among those who tested positive for cocaine. This result is consistent with the finding of an Australian study where intoxication by cannabis was not associated with binge drinking among young adults (McKetin et al., Citation2014), and a Swedish study of the general population that found that frequent cannabis use was negatively associated with hazardous alcohol use (Berge et al., Citation2014). A review article that investigated whether cannabis was complemented by or substituted alcohol consumption found that both situations were common; however, this type of use varied according to the studied population or setting due to cultural differences and the legal status of drug use (Risso et al., Citation2020).

Cocaine may sometimes be used to reduce the depressant effect of alcohol, particularly when drinking too much, while alcohol may also be used to increase the euphoric effect or alleviate some of the negative effects of cocaine, such as anxiety or twitching (American Addiction Centers, Citation2020; Pennings et al., Citation2002). A qualitative study interviewing 28 young adult nightclub patrons in Norway who used cocaine found that a common reason for using cocaine at nightclubs was to control, extend, and intensify drinking to intoxication (Edland-Gryt, Citation2021). These facts may explain the large proportion of cocaine users with high BAC as well as the increasing proportion of patrons who tested positive for cocaine during the early hours of the morning.

Studies have reported that the misuse of prescription drugs is common among club-goers in the USA (Kelly & Parsons, Citation2007; Kurtz et al., Citation2011). However, this was not the case in our sample of patrons, although the prevalence of prescription drugs was higher among those who tested positive for illicit drugs than among those who did not, particularly among those who tested positive for two or more drugs. It is possible that some nightlife patrons use sedatives or sleeping agents for a calming effect when coming home, and not in the nightclub setting itself. The most common combination was stimulants and benzodiazepines, which is also a common combination among drivers arrested for drug-impaired driving in Norway (Høiseth et al., Citation2014), and may indicate problematic drug use.

Very few patrons tested positive for opioids; two patrons had used heroin together with several other drugs; one tested positive for fentanyl, and six had used codeine or tramadol. None of the patrons tested positive for oxycodone or other opioids. While the recreational use of opioids is not common in Norway, the relative number of opioid-related fatalities is higher than in most other European countries. The main cause of opioid overdoses used to be heroin, but in recent years the numbers of fatal overdoses by oxycodone, methadone, and buprenorphine has increased (Simonsen et al., Citation2020).

The vast majority of those using illicit drugs in our study had consumed alcohol simultaneously, and about one-fifth of them tested positive for two or more illicit drugs. As polysubstance use increases the risk of harm, nightlife venues should introduce prevention programs to reduce the harm caused by illicit drugs and excessive alcohol consumption. Studies have found that harm reduction strategies that can be implemented at nightlife venues are management and staff training, law enforcement, and patron education (Akbar et al., Citation2011; Miller et al., Citation2009). Moreover, programs and interventions have been implemented to reduce alcohol and drug-related harm in the nightlife setting. For instance, the Healthy Nightlife Toolbox is an online database hosted and maintained by the EMCDDA (Citation2019a). It is designed for local, regional and national policy makers and prevention workers, and consists of databases on evaluated interventions and literature on alcohol and drug prevention in the nightlife scenario.

Another such program is the “Stockholm prevents alcohol and drug problems” (STAD)-project, which is an educational resource and research center for prevention of alcohol and drug abuse (Karolinska Institute, Citation2020). The “Club against Drugs” (CAD)-program, developed in 2001 and implemented and managed by STAD, is focused on drug training doormen and other staff, policy work, increased enforcement and environmental change (Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012). The implementation of CAD has resulted in a higher degree of interventions for apparently drug-intoxicated patrons (Gripenberg Abdon et al., Citation2011; Gripenberg et al., Citation2007).

Further, MHCS (Citation2005) has suggested a stronger enforcement to avoid acute problems related to drug intoxications, with or without alcohol. Stronger enforcement may, however, lead to violent responses, and they must therefore be used with care.

Several of the above-mentioned strategies may be effective in the Norwegian context. Effective strategies that can be implemented with ease are increasing the focus on alcohol and drug-related harm by educating doormen and bartenders, equipping them with tools to recognize signs of drug use and intoxication, and prohibiting entry and service for intoxicated patrons at nightclubs. In addition, information regarding the health risks of polysubstance use and treatment for problematic substance use should be promoted among nightlife patrons through posters, brochures, and informative videos. A combination of the aforementioned measures could be effective in reducing drug use and intoxication in nightlife settings since the responsibility lies with both the stakeholders and the patrons.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is that we confirmed alcohol use using a breathalyzer and drug use by analyzing samples of oral fluid using a sensitive, selective and accurate analytical method employing ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection.

However, this study also has a few limitations. The detection of alcohol in the breath or drugs in oral fluid indicates the presence of the substances in the body. The breath alcohol concentration reflects the BAC quite accurately. However, drinking within the last 20 min before the breath test may cause a higher alcohol value than the actual concentration in the blood. Moreover, drug findings in oral fluid do not always reflect the actual level of intoxication.

The analysis of NPS was limited to those that were most likely used based on seizure data from the Norwegian customs and police; therefore, we may have missed detecting some substances. However, the use of NPS is rare in Norway, thus, this limitation is unlikely to have had a significant effect on our findings and conclusions.

The recruitment procedure did not ensure a random selection of participants, and the participation rate was not recorded; therefore the study cohort was selected using convenience sampling. The research assistants sometimes had to assist the participants complete the written questionnaire, which could have introduced response bias.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that patrons who used illicit drugs before or during nightclub visits most often combined drug use with alcohol. The strongest correlates of illicit drug use, including the use of two or more illicit drugs during a short time frame, were being male, unemployed, using nicotine products, and early-onset illicit drug use.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Anne Line Bretteville-Jensen and Jasmina Burdzovic Andreas at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health for planning the data collection and providing valuable advice for the preparation of this manuscript. We also wish to thank the research assistants who collected the oral fluid samples and recorded the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This study was funded by Oslo University Hospital and The Norwegian Institute of Public Health with financial support from The Norwegian Health Directorate (Helsedirektoratet).

References

- Akbar, T., Baldacchino, A., Cecil, J., Riglietta, M., Sommer, B., & Humphris, G. (2011). Poly-substance use and related harms: A systematic review of harm reduction strategies implemented in recreational settings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(5), 1186–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.002

- American Addiction Centers. (2020). Mixing cocaine and alcohol: Effects and dangers. American Addiction Centers. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/cocaine-treatment/mixing-with-alcohol

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Bachman, J. G., Wadsworth, K. N., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., & Schulenberg, J. E. (1997). Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: the impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Baggio, S., Deline, S., Studer, J., N’Goran, A., Mohler-Kuo, M., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2014). Concurrent versus simultaneous use of alcohol and non-medical use of prescription drugs: Is simultaneous use worse for mental, social, and health issues?Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(4), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2014.921747

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Bennett, A., & Thomson, R. (2003). The role of an international nightlife resort in the proliferation of recreational drugs. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 98(12), 1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00554.x

- Berge, J. (2015). Substance use in adolescents and young adults. Interaction of drugs of abuse and the role of parents and peers in early onset of substance use. Lund University. https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/3234102/8228434.pdf

- Berge, J., Håkansson, A., & Berglund, M. (2014). Alcohol and drug use in groups of cannabis users: Results from a survey on drug use in the Swedish general population. The American Journal on Addictions, 23(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12097.x

- Bretteville-Jensen, A. L., Andreas, J. B., Gjersing, L., Øiestad, E. L., & Gjerde, H. (2019). Identification and assessment of drug-user groups among nightlife attendees: Self-reports, breathalyzer-tests and oral fluid drug tests. European Addiction Research, 25(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1159/000497318

- Calafat, A., Blay, N. T., Hughes, K., Bellis, M., Juan, M., Duch, M., & Kokkevi, A. (2011). Nightlife young risk behaviours in Mediterranean versus other European cities: Are stereotypes true?European Journal of Public Health, 21(3), 311–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq141

- Cavan, S. (1966). Liquor license: an ethnography of bar behavior. Aldine Publishing Company.

- Chomynova, P., Miller, P., & Beck, F. (2009). Perceived risks of alcohol and illicit drugs: Relation to prevalence of use on individual and country level. Journal of Substance Use, 14(3-4), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890802668797

- Comasco, E., Berglund, K., Oreland, L., & Nilsson, K. W. (2010). Why do adolescents drink? Motivational patterns related to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(10), 1589–1604. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826081003690159

- Connor, J. P., Gullo, M. J., White, A., & Kelly, A. B. (2014). Polysubstance use: Diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(4), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069

- Crummy, E. A., O’Neal, T. J., Baskin, B. M., & Ferguson, S. M. (2020). One is not enough: Understanding and modeling polysubstance use. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 569. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00569

- Degenhardt, L., & Hall, W. (2012). Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet (London, England), 379(9810), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0

- Degenhardt, L., Copeland, J., & Dillon, P. (2005). Recent trends in the use of "club drugs": An Australian review. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(9-10), 1241–1256. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-200066777

- Duff, C. (2008). The pleasure in context. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 19(5), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.07.003

- Edland-Gryt, M. (2021). Cocaine rituals in club culture: Intensifying and controlling alcohol intoxication. Journal of Drug Issues, 51(2), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042620986514

- Ellickson, P. L., Tucker, J. S., & Klein, D. J. (2003). Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics, 111(5 Pt 1), 949–955. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.5.949

- EMCDDA. (2015). European drug report 2015 - Trends and developments. Publications Office of the European Union. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/edr2015

- EMCDDA. (2018). Statistical Bulletin 2017 — prevalence of drug use. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2017/gps_en

- EMCDDA. (2019a). The healthy nightlife toolbox. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. http://www.hntinfo.eu/

- EMCDDA. (2019b). Statistical Bulletin 2019 — Prevalence of drug use. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2019/gps

- Fergusson, D. M., & Boden, J. M. (2008). Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction, 103(6), 969–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Foster, J. H., & Ferguson, C. (2014). Alcohol ‘pre-loading’: A review of the literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 49(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt135

- Gahlinger, P. M. (2004). Club drugs: MDMA, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), Rohypnol, and ketamine. American Family Physician, 69(11), 2619–2626. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/0601/p2619.pdf

- Gjerde, H., Gjersing, L., Furuhaugen, H., & Bretteville-Jensen, A. L. (2019). Correspondence between oral fluid drug test results and self-reported illicit drug use among music festival attendees. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(8), 1337–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1580295

- Gripenberg Abdon, J., Wallin, E., & Andréasson, S. (2011). The "Clubs against Drugs" program in Stockholm, Sweden: Two cross-sectional surveys examining drug use among staff at licensed premises. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-6-2

- Gripenberg, J., Wallin, E., & Andréasson, S. (2007). Effects of a community-based drug use prevention program targeting licensed premises. Substance Use & Misuse, 42(12-13), 1883–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701532916

- Gripenberg-Abdon, J., Elgan, T. H., Wallin, E., Shaafati, M., Beck, O., & Andreasson, S. (2012). Measuring substance use in the club setting: A feasibility study using biochemical markers. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597x-7-7

- Grov, C., Kelly, B. C., & Parsons, J. T. (2009). Polydrug use among club-going young adults recruited through time-space sampling. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(6), 848–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802484702

- Hayatbakhsh, M. R., Najman, J. M., Bor, W., Clavarino, A., & Alati, R. (2011). School performance and alcohol use problems in early adulthood: A longitudinal study. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY), 45(7), 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.10.009

- Henneberger, A. K., Mushonga, D. R., & Preston, A. M. (2021). Peer influence and adolescent substance use: A systematic review of dynamic social network research. Adolescent Research Review, 6(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00130-0

- Heradstveit, O., Skogen, J. C., Edland-Gryt, M., Hesse, M., Vallentin-Holbech, L., Lønning, K. J., & Sivertsen, B. (2020). Self-reported illicit drug use among Norwegian university and college students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 543507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.543507

- Hogg, M. A. (2013). Social identity and the psychology of groups. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 502–519). Guilford Press.

- Høiseth, G., Andås, H., Bachs, L., & Mørland, J. (2014). Impairment due to amphetamines and benzodiazepines, alone and in combination. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.013

- Johnson, M. B., Voas, R. A., Miller, B. A., & Holder, H. D. (2009). Predicting drug use at electronic music dance events: Self-reports and biological measurement. Evaluation Review, 33(3), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X09333253

- Johnson, P. B., & Richter, L. (2004). Research note: What if we’re wrong? Some possible implications of systematic distortions in adolescents’ self-reports of sensitive behaviors. Journal of Drug Issues, 34(4), 951–970. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260403400412

- Johnson, T., & Fendrich, M. (2005). Modeling sources of self-report bias in a survey of drug use epidemiology. Annals of Epidemiology, 15(5), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.09.004

- Karolinska Institute. (2020). STAD - Stockholm förebygger alkohol- och drogproblem [Stockholm prevents alcohol and drug problems]. http://www.stad.org/en/

- Kashdan, T. B., Vetter, C. J., & Collins, R. L. (2005). Substance use in young adults: Associations with personality and gender. Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.014

- Kelly, B. C., & Parsons, J. T. (2007). Prescription drug misuse among club drug-using young adults. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 33(6), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990701667347

- Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Levi-Minzi, M. A., & Mooss, A. (2011). Benzodiazepine dependence among multidrug users in the club scene. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 119(1-2), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.036

- Latvala, A., Rose, R. J., Pulkkinen, L., Dick, D. M., Korhonen, T., & Kaprio, J. (2014). Drinking, smoking, and educational achievement: Cross-lagged associations from adolescence to adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 137, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.016

- Listiak, A. (1974). Legitimate deviance” and social class: Bar behavior during Grey Cup Week. Sociological Focus, 7(3), 13–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.1974.10570891

- Martin, C. S. (2008). Timing of alcohol and other drug use. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 31(2), 96–99. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860457/pdf/arh-31-2-96.pdf

- McKetin, R., Chalmers, J., Sunderland, M., & Bright, D. A. (2014). Recreational drug use and binge drinking: Stimulant but not cannabis intoxication is associated with excessive alcohol consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12147

- Meyers, J. L., & Dick, D. M. (2010). Genetic and environmental risk factors for adolescent-onset substance use disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(3), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.013

- MHCS. (2005). Forskrift om omsetning av alkoholholdig drikk mv. (alkoholforskriften) - FOR-2005-06-08-538 [Regulations on the sale of alcoholic beverages, etc.]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2005-06-08-538?q=Forskrift%20om%20omsetning%20av%20alkoholholdig

- Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H. F., Branner, A. C., Voas, R., & Johnson, M. B. (2013b). Assessment of club patrons’ alcohol and drug use: The use of biological markers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.014

- Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H. F., Branner, A., Johnson, M., & Voas, R. (2013a). Group influences on individuals’ drinking and other drug use at clubs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(2), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2013.74.280

- Miller, B. A., Furr-Holden, D., Johnson, M. B., Holder, H., Voas, R., & Keagy, C. (2009). Biological markers of drug use in the club setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.261

- Miller, P., Droste, N., Martino, F., Palmer, D., Tindall, J., Gillham, K., & Wiggers, J. (2015). Illicit drug use and experience of harm in the night-time economy. Journal of Substance Use, 20(4), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2014.911974

- NIDA. (2019). National survey of drug use and health. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/national-drug-early-warning-system-ndews/national-survey-drug-use-health

- Nordfjaern, T., Edland-Gryt, M., Bretteville-Jensen, A. L., Buvik, K., & Gripenberg, J. (2016). Recreational drug use in the Oslo nightlife setting: Study protocol for a cross-sectional time series using biological markers, self-reported and qualitative data. BMJ Open, 6(4), e009306. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009306

- O’Hagan, A., & Smith, C. (2017). A new beginning: An overview of new psychoactive substances. Foresic Research & Criminology International Journal, 5(3), 00159. https://doi.org/10.15406/frcij.2017.05.00159

- Pennings, E. J., Leccese, A. P., & Wolff, F. A. (2002). Effects of concurrent use of alcohol and cocaine. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 97(7), 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00158.x

- Risso, C., Boniface, S., Subbaraman, M. S., & Englund, A. (2020). Does cannabis complement or substitute alcohol consumption? A systematic review of human and animal studies. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 34(9), 938–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120919970

- Schulte, M. T., & Hser, Y. I. (2013). Substance use and associated health conditions throughout the lifespan. Public Health Reviews, 35(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391702

- Simonsen, K. W., Kriikku, P., Thelander, G., Edvardsen, H. M. E., Thordardottir, S., Andersen, C. U., Jönsson, A. K., Frost, J., Christoffersen, D. J., Delaveris, G. J. M., & Ojanperä, I. (2020). Fatal poisoning in drug addicts in the Nordic countries in 2017. Forensic Science International, 313, 110343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110343

- Subbaraman, M. S., & Kerr, W. C. (2015). Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(5), 872–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12698

- Sussman, S., Skara, S., & Ames, S. L. (2008). Substance abuse among adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(12–13), 1802–1828. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802297302

- Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2006). Pharmacological content of tablets sold as "ecstasy": results from an online testing service. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83(3), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.016

- Valen, A., Øiestad, A. M., Strand, D. H., Skari, R., & Berg, T. (2017). Determination of 21 drugs in oral fluid using fully automated supported liquid extraction and UHPLC-MS/MS. Drug Testing and Analysis, 9(5), 808–823. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2045

- Van Havere, T., Vanderplasschen, W., Broekaert, E., & De Bourdeaudhui, I. (2009). The influence of age and gender on party drug use among young adults attending dance events, clubs, and rock festivals in Belgium. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(13), 1899–1915. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080902961393

- Van Havere, T., Vanderplasschen, W., Lammertyn, J., Broekaert, E., & Bellis, M. (2011). Drug use and nightlife: More than just dance music. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597x-6-18

- Voas, R. B., Furr-Holden, D., Lauer, E., Bright, K., Johnson, M. B., & Miller, B. (2006). Portal surveys of time-out drinking locations: a tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Evaluation Review, 30(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X05277285

- Vogels, N., Brunt, T. M., Rigter, S., van Dijk, P., Vervaeke, H., & Niesink, R. J. (2009). Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands: 1993-2008. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(12), 2057–2066. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02707.x

- von Sydow, K., Lieb, R., Pfister, H., Höfler, M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2002). What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence? A 4-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00102-3

- Winstock, A. R., Griffiths, P., & Stewart, D. (2001). Drugs and the dance music scene: a survey of current drug use patterns among a sample of dance music enthusiasts in the UK. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 64(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00215-5