Abstract

Background: Nighttime entertainment districts attract many people who pre-load with alcohol and other substances before entering licensed venues. Despite the harms and dangers associated with both alcohol pre-loading and drug use respectively, there is a paucity of research on drug and polysubstance pre-loading. Objectives: The primary objectives of this scoping review are to systematically map out the body of existing literature on drug and polysubstance pre-loading, discuss methodological potentials and pitfalls in field-based research, identify gaps in knowledge, and derive practical implications and opportunities for future research. Methods: Using the PRISMA (ScR) guidelines, we conducted a search of Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science databases. We followed this up by conducting an author and citation analysis of relevant articles. Results: Of the 632 data sources identified, 338 articles were reviewed after removing duplicates. Overall, only nine articles were included and thematically analyzed. In our review and analysis of the literature, we find people who drug pre-load to be a particularly vulnerable subset of the population. We also posit that the point-of-entry design has greater sensitivity than the commonly used portal-in design. From this, we also draw attention to various time points where field-based researchers can provide intervention. Conclusions: Given the high prevalence of young adults engaging in the behavior, clinicians should consider pre-loading behaviors when assessing for risk and vulnerability. Field-based research would elucidate the full breadth and scope of the growing pre-loading phenomenon and the dangers associated with this practice.

Background

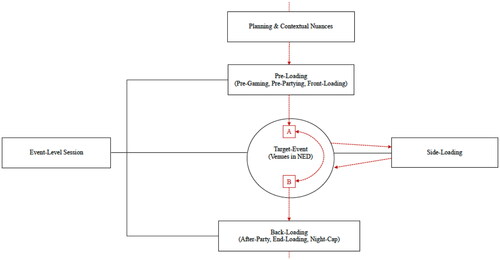

Pre-loading (also referred to as pre-gaming, pre-partying, front-loading, among other terms) with psychoactive substances before venturing into nighttime entertainment districts (NEDs) is a prevalent start to a night out for many people in the world (Devilly et al., Citation2017; Hughes et al., Citation2008; Østergaard & Andrade, Citation2014). In the present study, pre-loading is defined as the use of alcohol and/or other substances, either individually or in groups, at a private residence or closed space (e.g., at home, a friend’s house, or hotel/motel/hostel) and/or public space (e.g., a park, on public transport, suburban sports club/bar/pub), before going to a target-event (i.e., licensed night clubs and pubs within town NEDs; Hughes & Devilly, Citation2021). provides a visual representation of pre-loading as it pertains to the broader session at the event-level. The act of pre-loading commonly signifies the start to a ‘session’ of alcohol and/or drug useFootnote1 and typically occurs without the supervision or restrictions of licensed venues (Barton & Husk, Citation2014; Santos, Paes, Sanudo, & Sanchez, Citation2015). As such, it has been shown that people abuse substances (e.g., rapidly consuming excessive amounts of alcohol or potentially mix alcohol with energy drinksFootnote2 and/or other drugs) and engage in other risky behaviors (e.g., participating in drinking games and/or engage in heavy episodic drinking over a prolonged a period) given the freedoms pre-loading provides users (Østergaard & Andrade, Citation2014, Wells et al., Citation2009; Zamboanga & Tomaso, Citation2014). In effect, it is not surprising that people are entering NEDs highly inebriated (Devilly, Hides et al., Citation2019; Hughes et al., Citation2008) and requiring more resource intensive aid earlier in the night (Devilly & Srbinovski, Citation2019).

Figure 1. This model provides an updated visual representation of a ‘session’ at the event-level.

Note. The colored dotted line represents the trajectory a person makes as they transition through the phases of pre-loading, target-event, side-loadingFootnote5, and back-loadingFootnote6. It is to be noted that people may not participate in all phases of the session (e.g., a person may avoid ‘loading’ practices altogether and choose only to enter the target-event). The squares labeled ‘A’ and ‘B’ inside the target-event denote venues inside the NED. The doubled arrow connecting these venues reflects a persons’ movements around the NED.

For well over a decade, research examining pre-loading has garnered wide-spread attention from field-based researchers seeking to gain understanding and/or solutions to the harms experienced by people in and around licensed venues (Johnson, Citation2014; Van Geest et al., Citation2017). Although the literature-base has progressed considerably in this time, new and emerging trends have been identified in peoples’ pre-loading practices that present new conceptual, ethical, and methodological challenges for field-based researchers to overcome (Hughes & Devilly, Citation2021; Van Geest et al., Citation2017). Throughout this paper we endeavor to build upon this work by gaining a deeper understanding of drug pre-loading and how it has been measured in past field-research. In doing so, we hope to expand upon Foster and Ferguson’s (Citation2014) earlier seminal review of alcohol pre-loading and apply the principals of past methodological approaches to determine the most suitable approach moving forward.

Chasing perspective on a bigger picture

To date, most documented investigations into pre-loading have focused specifically on alcohol use only. Whilst much of this research output has provided a solid foundation to build upon, there is a paucity of research focused specifically on understanding the pre-loading practices of drug users. Consistent with this, past research has either focused on alcohol pre-loading or drug use, and not the interaction between them. To gain greater perspective on this problem, we posit that there is an on-going need to explore the use of other licit and illicit substances at pre-loading events, as well as peoples’ participation in other maladaptive practices such as polysubstanceFootnote3 use and/or side- and back-loading). To do so warrants further consideration because: (a) epidemiological research has demonstrated that people use both alcohol and drugs, and the combined use of substances by patrons is not an uncommon occurrence after having transitioned into nightclubs and pubs (DeJong et al., Citation2010; Devilly, Hides et al., Citation2019; Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Voas et al., Citation2013); (b) to overlook certain important aspects of an issue (i.e., people pre-load with drugs as well as alcohol) can provide an inaccurate depiction of peoples’ pre-loading practices, which in turn may not reflect the true breadth and severity of harm associated with its occurrence; and (c) people who pre-load with both alcohol and drugs likely reflect a subset of the population that is perhaps more vulnerable than those who only pre-load with alcohol. Although it is yet to be quantified, it must be considered that drug and alcohol pre-loading would only further exacerbate the potential for harm. However, the inclusion of assessing for drugs in NEDs presents several methodological challenges that need to be identified for future reference.

Scoping reviews

Over the past decade, scoping reviews have become an increasingly popular approach among researchers seeking to probe further into emerging topics and reveal unexplored avenues in areas of research (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014; Khalil et al., Citation2021; Levac et al., Citation2010; Peters et al., Citation2020). In line with Colquhoun et al’s. (2014) definition of this research approach, we operationalize a scoping review as being a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a particular field of study by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing literature (Aucoin et al., Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2015). Scoping reviews are designed to identify and describe the breadth of literature on a topic when it is either:

Highly complex. The act of pre-loading is highly prevalent inside NEDs, and occurs across various other contexts (e.g., e.g., sport events, college dorms, etc.) and geographical locations (e.g., Oceania [Devilly, Greber et al., Citation2019; MacLean & Callinan, Citation2013; McCreanor et al., Citation2016; O’Rourke et al. Citation2016; Riordan et al, Citation2018]; European countries [Barton & Husk, Citation2014; Boyle et al., Citation2009; Elgàn et al., Citation2019; Howard et al, Citation2019; McClatchley et al., Citation2014]; United States of America/South America [Moser et al., Citation2014; LaBrie et al., Citation2012; Pedersen & LaBrie, Citation2007; Pilatti & Read, Citation2018; Zamboanga & Olthuis, Citation2016]; Canada [O’Neil et al. Citation2016]; and most recently India [Rajaseharan & Dongre, Citation2021]). Although pre-loading is by no means a recently scrutinized topic, the strategic and progressive nuances of peoples’ pre-loading practices make addressing the issue a complex task. Some complexities include the challenges associated with operationalizing pre-loading, selecting terminology specific to alcohol (e.g., pre-drinking) or geographical location, and navigating methodological issues due to the evolving nature of this practiceFootnote4.

Involves a broad array of study designs. Obtaining a more complete and accurate depiction of peoples’ pre-loading practices is pertinent to the development of more targeted and effective interventions in the long-term. In the past, researchers have examined alcohol-only pre-loading using a vast array of measures and design approaches, including portal design (e.g., Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Johnson et al., Citation2013; Santos, Paes, Sanudo, & Sanchez, Citation2015) and point-of-entry designs (e.g., Devilly et al., Citation2017; Devilly, Hides et al., Citation2019; Devilly, Greber et al., Citation2019). Portal survey designs are a form of intercept sampling designed to assess at-risk individuals entering and exiting licensed venues (Voas et al., Citation2006), as opposed to people entering and exiting the NED. Moreover, field researchers in NEDs have incorporated validated objective measures of alcohol and drug use in their methodologies (e.g., breathalyzer devices or saliva drug testing kits), which increases the richness of the data obtained (e.g., Sorbello et al., Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2009). Accordingly, a synthesis and review of past research designs may provide greater methodological clarity moving forward with the inclusion of assessing for drugs.

When a comprehensive review is being completed for the first time. In effect, scoping reviews are of great benefit when there is a need to: advance a field of research; inform practice and policy agendas; and guide researchers in future decision making (Levac et al., Citation2010; Peters et al., Citation2020). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review conducted specifically on drug and polysubstance use in NEDs. Although Foster and Ferguson (Citation2014) addressed the topic of alcohol pre-loading in their review of the literature, the link between alcohol pre-loading and drug use was not examined.

Review objectives

In this study we conduct a scoping review of available field-based evidence that links drug use to alcohol pre-loading before people enter NEDs. The key objectives of this research are to systematically map out the body of existing literature on drug and polysubstance pre-loading, discuss methodological potentials and pitfalls in field-based research, identify gaps in knowledge, and derive practical implications and opportunities for future research. As such, our hope is that the present study will complement and extend upon Foster and Ferguson’s (Citation2014) systematic review of alcohol pre-loading.

Methodology

Reporting of this scoping review was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (see supplementary information 1; Tricco et al., Citation2018). This scoping review was informed by the guidelines developed by Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) and the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020; Peters et al., Citation2021). Our approach was also guided by the works of Levac and colleagues (Citation2010) and Khalil et al. (Citation2016, Citation2021) on scoping review methodology. The review followed five key stages: (1) formulating the research questions; (2) detailing the search strategy; (3) selecting relevant research; (4) extracting the data; and (5) analyzing the results. In line with our operational definition of pre-loading, we used the PCC (population [patrons], concept [drug and polysubstance pre-loading], and context [NEDs]) mnemonic to foster clarity when formulating our exploratory research questions and to guide subsequent stages of the framework protocol (Peters et al., Citation2020). The research protocol is registered in the Open Sciences Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/SD246).

Research questions

This scoping review has both substantive and methodological research questions. Our substantive research question is: (1) What information and/or literature is available on patrons who pre-load with drugs before transitioning into NEDs? In answering this question, we placed specific focus on (a) what demographic variables correlate with drug pre-loading; (b) the prevalence of drug/polysubstance pre-loading behaviors among people entering NEDs; (c) what drug/polysubstance configurations are most popular among pre-loading patrons; and (d) differences in alcohol inebriation levels between people who pre-load with drugs and those who only pre-load with alcohol. Our methodological research question is: (2) What is the quality of existing information and/or literature in terms of evidence base, impact and utility, and generalizability? More specifically, which field-based methodological designs provide the greatest utility for future reference? From these research questions we established search concepts (i.e., drug misuse, pre-loading, and nighttime entertainment districts) as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria (which was refined iteratively throughout the search process).

Search strategy and study selection

To identify relevant information, we first conducted a pilot search using the Google search engine and Griffith University library catalogue to identify terms that are synonymous with the concept of pre-loading (cf. Hughes & Devilly, Citation2021), substance description (i.e., generic/common/street names), and context (e.g., nighttime: entertainment district/precinct/economy). This initial reconnaissance was done to ensure our subsequent searches were sensitive to cultural and geographical differences in terminology. Subsequently, we consulted a library technician from Griffith University Researcher and Academic Services to assist in the development of a preliminary search strategy. The purpose of conducting a preliminary search was to translate and standardize search syntax and to test for retrieval of relevant articles between each electronic databases (i.e., Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, and Web of Science). These electronic data bases were chosen to cast a wide net over the current literature, particularly as the risks and harms associated with pre-loading negatively impact a variety of fields and professions (e.g., nursing, political science, and social services). Prior to finalizing our search strategy, we had our most recent preliminary search peer-reviewed by a second library technician (from the same institution) for the purpose of further refining our approach (Peters et al., Citation2020). Once finalized, we again searched each respective database for relevant sources of information.

Each search strategy iteration involved the use of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Proximity operators, Boolean operators, truncation symbols, and search fields to expand and/or narrow the focus of our searches. The use of abbreviated terminology was used sparingly. Common abbreviated terms used across different geographical locations were included in the final search (i.e., those used to identify a drug), while those that are less frequently used or varied in their association (e.g., NED and NTE) were excluded from the final search due to the high volume of irrelevant articles found. See supplementary information 2 for the finalized search syntax and results for each respective database.

We used Covidence reference management software to import and organize the citations of identified articles yielded from the search strategy. All duplicate articles were removed before screening and assessing the remaining articles for inclusion. The selection of empirical research was an iterative process that involved the following steps: (1) both authors independently reviewed and selected relevant publications based on the information contained in the titles and abstracts to identify eligibility for full-text review; (2) studies considered eligible for full-text were then sourced and assessed for selection; (3) the authors met to discuss discrepancies (there was no disagreement between the authors regarding study selection) and refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see below); and (4) we also screened the reference lists of full-text articles to determine if there were any additional studies eligible for screening. This process involved searching for the title of a study as well as the names of the author/s and their publication lists. We used Research Gate, Griffith University library data base, and Google Scholar to facilitate this process as well as aid in the discovery of grey literature (we considered university and government reports, and news articles)—none was identified that met the inclusion criteria. We also reviewed the reference lists of past event-level reviews (e.g., Brooks et al., Citation2019; Clapp et al., Citation2007; Foster & Ferguson, Citation2014; Morrison et al. Citation2015; Palamar et al., Citation2021; Stevely, Holmes, McNamara et al., Citation2020; Stevely, Holmes, & Meier, Citation2020). Phases 1—3 were then repeated until the selection of empirical articles was finalized. See supplementary information 3 for a visual representation of our methodology following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria across all studies.

Data extraction and analysis

Extracting the data was an iterative process and a proforma was developed to capture the authors, year of publication, study objectives, sample characteristics, methodology used, and key findings. All data extracted and charted can be observed in . Both authors reviewed the full-text articles and extracted the data independently to mitigate the chance of errors and bias (Peters et al., Citation2020). All discrepancies were solved by the authors through re-reading and discussing the article, with no third-party consultation required to resolve issues of non-consensus. The results are summarized in tables and figures where possible to assist in the visualization of a concept or theme. We used a thematic narrative approach to highlight trends and gaps that warrant further investigation.

Table 2. A summary table demonstrating the key features of the nine studies included.

Results

Characteristics of the references

Overall, we identified nine studies that met our inclusion criteria. These investigations were published between 2005 and 2021. All studies included were event-level field-based investigations conducted around licensed nightclubs, pubs, and bars located within NEDs. Studies reporting on the prevalence of drug use and pre-loading behaviors were conducted by research teams operating out of Australia, North America, and South America.

The individual and contextual nuances of drug pre-loading

To gain insight on the characteristics of people who pre-load with drugs, we looked for key themes in field-based studies using portal-in and point-of-entry designs. These findings should be interpreted with caution as much of the drug related information we identified was collected from studies that did not explicitly investigate pre-loading behaviors. Nevertheless, we identified the following themes:

Alcohol was the most used substance across all studies, with a smaller minority admitting and/or testing positive for drugs.

Polysubstance use (i.e., the use of both alcohol and drugs simultaneously) was a common occurrence among drug users.

Of drug users, cannabis use was the most used substance followed by cocaine and other stimulant type drugs (i.e., 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA], amphetamines, and methamphetamines). The use of other substances was far less prevalent in this context.

No consistent themes were identified regarding the personal characteristics of drug users other than they tended to be male, heterosexual, and employed full-time. Positive results on drug oral assays increased with age, however, this trend was not significant.

Drug use was associated with engagement in high-risk behaviors such as polysubstance use, driving while intoxicated into the NED (specifically the use of cocaine), and engagement in heavy episode drinking.

The similarities and differences of applied methodologies

All studies comprised an ethnically diverse sample of participants and there was little variation between age (i.e., number of participants increased as age bracket decreased across all studies) and gender (relatively balanced between males and females). All studies used a mix of subjective (self-report) and objective (breathalyzer devices and/or oral assays) measures to mitigate over- and under-reporting and other self-report biases. We consider the use of BrAC devices and confirmatory drug testing measures a key strength to this research. As seen in , study participation rates varied between geographical locations. However, there were some key methodological differences between the research teams. These differences include:

Australia researchers used a point-of-entry design, whereas the North and South American research teams both surveyed participants using the portal design.

Drug testing was only obtained using objective markers by the North American research team, whereas Australian and South American research teams relied on self-report measures. In turn, the North American studies tended to find much higher estimates of drug use than the Australian and South American studies. The Australian and South American research teams provided prevalence estimates only, whereas the North American research team provided prevalence estimates and descriptors characteristics of those who used drugs in some studies.

The Australian and North American research teams specify that participants were randomly (or systematically random) selected, whereas it is unclear if this was the case for the South American research team.

The North American researchers offered financial incentives, whereas the Australian and South American research teams did not (unless unspecified in the article).

The North and South American research teams reported factors impacting participation included being in a rush, hesitance around participation, and severe intoxication.

The South American research team stipulated that they opted to exclude individuals believed to be heavily intoxicated, whereas the Australia and North American research teams did not. While this may have been stipulated as an ethical condition to preserve and protect the safety of researchers, estimates pertaining to a vulnerable subset of the population were missed (Devilly, Citation2018; Ryan et al., Citation2019). To overlook this could be regarded as a limitation due to the potential effects of nonresponse bias (Johnson, Citation2014).

The Australian research team reported having police present throughout periods of data collection (although without the police seeing responses), whereas both research teams from North and South America did not. While there is a need to collect data from drug users in this context, the impact police presence had on participation is currently unknown.

An analysis of field-based methodologies

We identified three primary methodological approaches used to capture estimates of pre-loading (irrespective of substance used). Inherent within these designs, participants are recruited cross-sectionally over the course of the session; as people portal-in to a licensed venue; or as people enter (i.e., point-of-entry) into a NED. These approaches all utilized different and distinct designs that, when compared against one another, offer different levels of sensitivity and specificity.

A methodological note on retrospective and cross-sectional designs

Cross-sectional and retrospective reporting were commonly used to collect data from participants over the course of the night. Overall, we consider this approach to show the least amount of sensitivity and specificity in field-base pre-loading research. A problem associated with this approach is that incidentally collecting data from participants at different time frames will likely yield inconsistent results. For instance, obtaining accurate BrAC estimates on alcohol pre-loading intoxication will be impacted if a person has already transitioned into licensed venues and continued consuming alcohol. Consistent with this, retrospective and cross-sectional designs also demonstrate susceptibility to memory errors and other self-report and sampling biases (c.f., Devilly et al., Citation2017). Another problematic theme observed in cross-sectional studies stemmed from the use of substance-specific terminology such as ‘pre-drinking’ and ‘drug use’. Unless explicitly specified in the article, one cannot ascertain whether these practices occurred together or independent of one another at different times throughout the session (see Hughes & Devilly, Citation2021 for further discussions on this). In our review of the literature and to the best of our knowledge, we were unable to identify a single article that made this distinction using this approach. It is for these reasons that we excluded retrospective and cross-sectional studies from our results table.

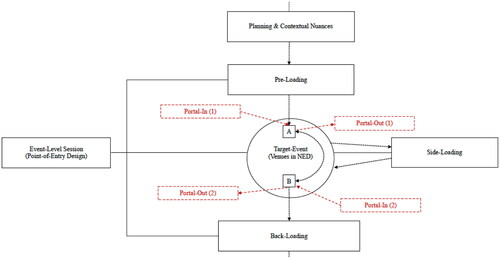

An overview of the portal-in design

Portal surveys are a form of intercept sampling designed to assess at-risk individuals who enter and exit licensed venues (Voas et al., Citation2006). provides a visual representation of how portal surveying aligns in conjunction with the broader event-level session. In our review of the literature, this approach has been used in Australia (Lubman et al., Citation2014) and shown to be popular among field-based researchers in the United States of America (e.g., Johnson et al., Citation2015; Byrnes et al., Citation2016; Byrnes, et al., Citation2019), South America (Carlini & Sanchez, Citation2018; Sañudo et al., Citation2015, Wagner & Sanchez, Citation2017), and Europe (Gripenberg-Abdon et al., Citation2012). Only the studies included in provide prevalence estimates of drug and alcohol use as people portal-in to a venue. In their description of this design, Voas et al. (Citation2006) describes three prerequisites that are required from the environment for this approach to be deemed appropriate for measuring peoples’ substance use practices in NEDs. These prerequisites include:

Figure 2. A visual representation of the portal design applied to the broader event-level session.

Note. Portal-in (1) reflects the best point in time for the accurate collection of pre-loading data. However, any reference to the act of pre-loading should be discerned from portal-in (2).

Be a venue associated with increased risk of substance misuse.

Exist in a location that permits intercepting and assessing peoples’ substance use upon entering and exiting the establishment.

Have people who enter and exit during a sufficient timeframe to permit participation to occur.

Most of the portal design studies outlined in refer to the act of pre-loading (or pre-drinking). However, it is often unclear whether the participants being assessed had a) transitioned out of the pre-loading phase and not yet entered a licensed venue; or b) already transitioned into the NED and consumed substances once inside licensed venues. Without this distinction caution should be taken when making inferences about drug pre-loading as it is unclear when and where the substances were used (Foster & Ferguson, Citation2014; Hughes & Devilly, Citation2021). Despite these concerns, these findings do provide the best approximation of what could be occurring among people who pre-load with drugs. Although it might be the case that some of their samples had consumed substances at a different venue within the target-event, these studies would have captured valid estimates of pre-loading in those making their first portal-in to a venue.

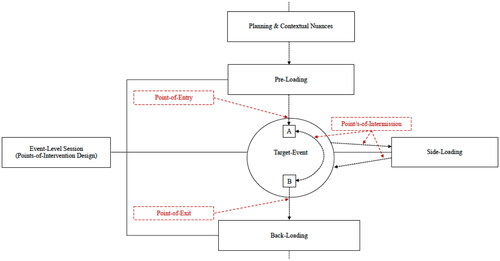

An overview of the point-of-entry design

Point-of-entry designs are another form of intercept sampling. Rather than collecting data occurring immediately before people enter a licensed venue, this occurs as people enter the NED. provides a visual representation of how a point-of-entry design occurs when applied to the broader event-level session. In contrast to the previous two designs, greater confidence can be placed on the conclusions drawn from this approach because there is some assurance that people have not yet transitioned into the NED where they continued to ingest substances. Like with portal surveying the same prudence should still be taken to ensure people have not made this transition. In line with Voas et al’s. (2006) prerequisites for portal surveying in this context, a point-of-entry design shares many of the same requirements. In the case of pre-loading, we suggest the following amendments are made:

Figure 3. A visual representation the point-of-entry design as applied to the broader event-level session.

Note. This approach captures pre-loading estimates as people transition from the pre-loading event and into the target-event. We have also specified various points-of-intermission and the point-of-exit as a methodological note for future reference.

Be a space associated with increased risk of substance misuse (i.e., the pre-loading event), as opposed to being just a venue.

Exist in a location that permits intercepting and assessing peoples’ substance use upon transitioning from a pre-loading event and into a target-event (i.e., the NED), rather than upon entering and exiting an establishment.

Ensure people transitioning between events have a sufficient timeframe to permit participation to occur. In contrast to major events where people often enter and exit in large groups, the nature of the NED environment ensures a slower and more gradual transition timeframe. Therefore, intercepting people making their transition into a licensed venue is a manageable undertaking.

Point/s-of-intervention (a reconceptualized multi-function approach)

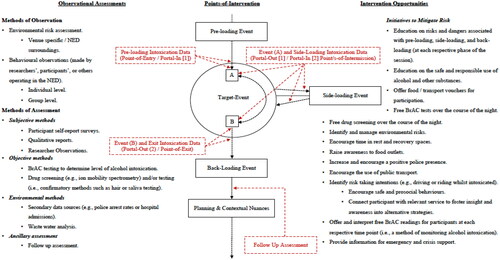

As it pertains to space and time, both portal-in designs and point-of-entry designs provide the necessary requirements to capture estimates of pre-loading behaviors. As it currently stands, point-of-entry designs provide the greatest sensitivity for the collection of pre-loading related data. Portal-in surveys require greater prudence and transparency than do point-of-entry designs to ensure one is reliably measuring pre-loading. In contrast to other cross-sectional approaches, we consider operationalizing a specific intercept time to be a strength to both approaches. A key strength inherent within portal designs is that this approach has been used to precisely link a participant’s intoxication to drugs and alcohol within a specific location (Morrison et al. Citation2015; Voas et al., Citation2006). When applied to the event-level model, portal surveying could also be regarded as a useful approach to better understanding the contextual nuances of peoples’ side-loading practices. In summary, there is some overlap between the portal design and point/s-of-entry, -intermission, and -exit designs. A key distinction being that portal designs (in- and -out) can serve multiple unique functions when examining ‘loading’ type practices, but in doing so, the construct of interest needs to be clearly operationalized within the methodology. We have sought to capture the essence of both approaches by amalgamating them into a single unified model, see .

Figure 4. A visual representation the point/s-of-intervention design as comprised within our model of an event-level session.

Note. In this figure we have labeled specific reference points where ‘loading’ and ‘event’ specific estimates of intoxication are most reliably captured. Additionally, we have also mapped on to this model points/s-of-intervention for future researchers to consider implementing into their designs to alleviate the burden of harm people experience in this context.

To extend on this idea further, we consider Kelly-Baker, Voas, Johnson, Furr-Holden, and Compton’s (2007) seminal review of multi-method assessments (i.e., self-report, biological, and observational) in high-risk environments such as NEDs (Kelley-Baker et al. Citation2007). In effect, we can apply their multi-method approach to our model and examine time points throughout the session where there is opportunity for intervention. At the core of this model lie several specific timepoints over the course of an event-level session where contact is made with an at-risk population. In field research this provides opportunity for researchers to make observational assessments of the environment and behavior at the individual and group level. Engaging with and surveying people could be regarded as an intervention given it provides opportunity for people to take a break from using substances, whilst also gaining insight and awareness into their level of intoxication. Collecting data at these specific timepoints provides a space for people to report on their experience at the event-level which, in turn, provides opportunity for more strategic interventions to be developed and employed.

Discussion

This scoping review summarizes published work on the topic of drug and polysubstance pre-loading practices of people before transitioning into NEDs. In turn, the purpose of this scoping review was to shed light on the current literature base for substantive and methodological purposes moving forward. Although this is not the first review of the pre-loading literature (c.f. Foster & Ferguson, Citation2014), it is the first to collate a broad range of resources focusing on the link between alcohol pre-loading and drug use in this context. As such, we view our results and interpretation of them as being unique in this regard. From our analysis and critique of field-based designs we were able to amalgamate past methodological approaches. This led to the development of our point/s-of-intervention design (). In the context of the broader session at the event-level, this multi-method approach can serve several functions. Conceptually, the model itself provides a simple visual representation of how a session can look for people on a night out. Methodologically, it fosters sensitivity and specificity as there are specific time-points identified where markers of intoxication can be measured, and ‘loading’ type behaviors can be differentiated. Practically, this model methodically highlights areas where there is opportunity for intervention and environmental risk assessments to take place, as well as the role researchers can have to facilitate this. Drawing on past field-based research, we were able to take this one step further by mapping some of the interventions we identified onto our event-level model. Our hope is that these findings would assist in the development of interventions targeting risky and harmful use of substances within the NED environment.

The utility of this scoping review, and strengths of the conclusions drawn, was limited by the availability of identifiable resources on the topic. First and foremost, we set out to better understand the nature of drug pre-loading. However, in reviewing different field-based methodologies it became evident that we were only able to provide a close approximation of what could be occurring during this phase of the session. This was because much of what was deduced came from portal design studies, as opposed to those using the point-of-entry design. While we acknowledge that it would have been preferrable to avoid introducing potential error into our results section, we were posed the dilemma of reporting something that provides a close approximation of pre-loading or report nothing at all. We chose the former option because a) hopefully it provokes discussion and further enquiry into the topic; b) there was a need to consolidate and build upon the past seminal works of Foster and Ferguson (Citation2014), the south American research team (i.e., Sanchez and colleagues), and north American research team (i.e., Miller, Voas, and colleagues); c) there is an on-going and continued need for methodologies that adequately describe and understand the nature of peoples’ substance use practices at the event-level; and d) it is evident that the earlier a person misuses substances, the greater the risk of harm they are to themselves and others in this context.

In effect, NEDs attract many people that have pre-loaded with substances before their arrival to the area. While most people pre-load with alcohol, there is a smaller and potentially more vulnerable subset of this population that was using drugs (at least admittedly). Considering the harms associated with alcohol pre-loading and the paucity of research on drug pre-loading, it is evident further enquiry is required. Specifically, there is a need to determine what demographic pre-loads with drugs; explore what drugs and polysubstance combinations people typically pre-load with; examine why people pre-loaded with drugs; and obtain reliable and valid measures of how intoxicated people are as they enter NEDs. To overcome the conceptual gaps identified in our review, future field-based researchers should not underestimate the importance of providing a clear operational definition of pre-loading (or any other loading and event specific practice or methodological approach). Likewise, to overcome some of the ethical and methodological gaps we identified, future research should consider: using the point-of-entry design to obtain pre-loading data; recruiting participants at random and reporting rejections rates; collecting data in the absence of police to determine what impact this could have on rates of self-disclosure; employing a within-subjects design to capture and discern drug related differences from point-of-entry to point-of-exit; and incorporating objective measures where possible to mitigate measurement error. To obtain data under these conditions would greatly assist in the development of more targeted interventions designed to mitigate the harms this vulnerable population experiences inside NEDs at the community level. Moreover, we speculate that findings of such research would be of benefit to the police and other emergency services, venue staff and security, key stakeholder groups, academics invested in the field, as well as policy developers and other government officials.

Moving forward, we posit that future research should also consider implementing a qualitative element into their methodological approach. To date, most field-research into pre-loading has been quantitative in nature. While statistics provide a good general overview of patterns of substance use, greater depth is required to better understand the mechanisms underpinning pre-loading and the risks involved (Barton & Husk, Citation2014). To obtain such information would prove useful for clinicians that work therapeutically with such vulnerable populations in clinical setting. This is particularly the case where there is a need to conduct thorough risk assessments and develop safety plans for people who frequent NEDs. With such high prevalence rates of young people engaging in this practice, conducting in-depth interviews with young adults would also shed light on why pre-loading has become so entrenched in contemporary party culture. As it currently stands, there appears to be a fundamental disconnect within the literature around what motivates people to pre-load. In quantitative research it is often reported that people do so to save money (Read et al., Citation2010) or to socialize (e.g., Devilly et al., Citation2017; MacLean & Callinan, Citation2013), while qualitative findings suggest that people prefer to pre-load for reasons of safety and control over the environment (Barton & Husk, Citation2014). From a clinical perspective, all these reasons are important factors to consider in case formulation, but they fall short of identifying the underlying internal problems people experience (Feingold & Tzur Bitan, Citation2022).

With a deeper understanding of what internal problems they typically experience, we can then work to identify themes pertaining to what people perceive as benefits of behaving in accordance with their motivations in cases where harm is experienced. For clinicians working with at-risk individuals, the utility of this may provide greater insight into peoples’ maladaptive pre-loading practices and self-regulatory behaviors at the individual level, which in turn could assist in the development of more targeted treatment plans and risk assessments. Moreover, assessing the pre-loading practices of young adults could be a prudent decision when looking more closely at the main types of drugs used. For instance, there is a growing body of research linking the co-occurrence of cannabis use and mental health issues like depression (Feingold & Weinstein, Citation2020). Given the high incidence rates of cannabis use among drug pre-loaders, this could be an avenue for research and intervention for depression. In essence, more research is needed to better understand this harmful cultural phenomenon so we can best manage it within the community as well as an individual or clinical level.

Authors’ contributions

Hughes and Devilly conceptualized the idea, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper together. Hughes liaised with University librarians to develop the search syntax and conducted the literature search.

License to publish

Exclusive license to publish this article is given.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (272.5 KB)Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this manuscript the term ‘drug use’ is used in reference to the consumption of illicit substances (i.e., the substance was manufactured, distributed, and/ or consumed for recreational purposes and not to treat a medical condition under the supervision of health care professional).

2 An energy drink is one that contains a high percentage of sugar, caffeine, and/ or another stimulant (e.g., ‘Red Bull’, ‘V’, or pre-workout exercise supplements), which have been designed to help consumers overcome fatigue by providing them with a sudden boost of energy. This definition does not extend to include soft drinks containing caffeine (e.g., cola).

3 Polysubstance use refers to the consumption of more than one substance, simultaneously or at different times, over a session of substance use (Connor et al., Citation2014). We consider this to include the mixing of both licit and/or illicit substances (e.g., the combined use of alcohol and cocaine or alcohol and energy drinks).

4 See Hughes and Devilly (Citation2021) for a more detailed discussion on the complexities associated with researching pre-loading in field-based research.

5 Side-loading refers to the use of one or more substances that have been smuggled into the target-event and/or whilst transitioning between licenced premises after having transitioned into the NED (O’Rourke et al., Citation2016).

6 Back-loading refers to the use of a substance/s after having transitioned out of a specified target-event (Forsyth, Citation2010).

7 Samples reported are comprised of entry only data / concordance data from entry to exit.

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Aucoin, M., Lachance, L., Naidoo, U., Remy, D., Shekdar, T., Sayar, N., Cardozo, V., Rawana, T., Chan, I., & Cooley, K. (2021). Diet and anxiety: A scoping review. Nutrients, 13(12), 4418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124418

- Barton, A., & Husk, K. (2014). “I don’t really like the pub […]”: Reflections on young people and pre-loading alcohol. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 14(2), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-12-2013-0055

- Boyle, A., Wee, N., Harris, R., Tompkins, A., Soper, M., & Porter, C. (2009). Alcohol-related emergency department attendances, preloading and where are they drinking? cross-sectional survey. Emergency Medicine Journal, 26(Suppl 1), 27–27. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2009.082099a

- Brooks, M., Nguyen, R., Bruno, R., & Peacock, A. (2019). A systematic review of event-level measures of risk-taking behaviors and harms during alcohol intoxication. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106101–106101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106101

- Byrnes, H. F., Miller, B. A., Bourdeau, B., & Johnson, M. B. (2019). Impact of group cohesion among drinking groups at nightclubs on risk from alcohol and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues, 49(4), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042619859257

- Byrnes, H. F., Miller, B. A., Bourdeau, B., Johnson, M. B., & Voas, R. B. (2016). Drinking group characteristics related to willingness to engage in protective behaviors with the group at nightclubs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000142

- Byrnes, H. F., Miller, B. A., Johnson, M. B., & Voas, R. B. (2014). Indicators of club management practices and biological measurements of patrons’ drug and alcohol use. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(14), 1878–1887. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.913630

- Carlini, C. M., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2018). Typology of nightclubs in São Paulo, Brazil: Alcohol and illegal drug consumption, sexual behavior and violence in the venues. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(11), 1801–1810. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1435067

- Clapp, J. D., Holmes, M. R., Reed, M. B., Shillington, A. M., Freisthler, B., & Lange, J. E. (2007). Measuring college students’ alcohol consumption in natural drinking environments: Field methodologies for bars and parties. Evaluation Review, 31(5), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X07303582

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- Connor, J. P., Gullo, M. J., White, A., & Kelly, A. B. (2014). Polysubstance use: Diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(4), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069

- DeJong, W., DeRicco, B., & Schneider, S. K. (2010). Pregaming: An exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 58(4), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480903380300

- Devilly, G. J. (2018). “All the King’s horses and all the King’s men…”: What is broken should not always be put back together again. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 51, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.020

- Devilly, G. J., & Srbinovski, A. (2019). Crisis support services in night-time entertainment districts: Changes in demand following changes in alcohol legislation. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 65, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.12.007

- Devilly, G. J., Allen, C., & Brown, K. (2017). SmartStart: Results of a large point of entry study into preloading alcohol and associated behaviours. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 43, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.013

- Devilly, G. J., Greber, M., Brown, K., & Allen, C. (2019). Drinking to go out or going out to drink? A longitudinal study of alcohol in night-time entertainment districts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107603

- Devilly, G. J., Hides, L., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2019). A big night out getting bigger: Alcohol consumption, arrests, and crowd numbers, before and after legislative change. PloS One, 14(6), e0218161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218161

- Elgàn, T. H., Durbeej, N., & Gripenberg, J. (2019). Breath alcohol concentration, hazardous drinking and preloading among Swedish university students. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift: NAT, 36(5), 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072519863545

- Feingold, D., & Tzur Bitan, D. (2022). Addiction psychotherapy: Going beyond self-medication. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 820660–820660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.820660

- Feingold, D., & Weinstein, A. (2020). Cannabis and depression. Cannabinoids and neuropsychiatric disorders (pp. 67–80). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57369-0_5

- Forsyth, A. J. M. (2010). Front, side, and back-loading: Patrons’ rationales for consuming alcohol purchased off-premises before, during, or after attending nightclubs. Journal of Substance Use, 15(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659890902966463

- Foster, J., & Ferguson, C. (2014). Alcohol ‘pre-loading’: A review of the literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 49(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt135

- Fung, E. C., Santos, M. G. R., Sanchez, Z. M., & Surkan, P. J. (2021). Personal and venue characteristics associated with the practice of physical and sexual aggression in Brazilian nightclubs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP3765–NP3785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518780783

- Gripenberg-Abdon, J., Elgán, T. H., Wallin, E., Shaafati, M., Beck, O., & Andréasson, S. (2012). Measuring substance use in the club setting: A feasibility study using biochemical markers. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-7

- Howard, A. R., Albery, I. P., Frings, D., Spada, M. M., & Moss, A. C. (2019). Pre-partying amongst students in the UK: Measuring motivations and consumption levels across different educational contexts. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(9), 1519–1529. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1590414

- Hughes, K., Anderson, Z., Morleo, M., & Bellis, M. A. (2008). Alcohol, nightlife and violence: The relative contributions of drinking before and during nights out to negative health and criminal justice outcomes. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 103(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02030.x

- Hughes, L. R. J., & Devilly, G. J. (2021). A proposal for a taxonomy of pre-loading. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(3), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1869261

- Johnson, M. B., Voas, R., Miller, B., Bourdeau, B., & Byrnes, H. (2015). Clubbing with familiar social groups: Relaxed vigilance and implications for risk. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(6), 924–927. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2015.76.924

- Johnson, T. P. (2014). Sources of error in substance use prevalence surveys. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014, 923290–923221. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/923290

- Kelley-Baker, T., Voas, R. B., Johnson, M. B., Furr-Holden, C. D. M., & Compton, C. (2007). Multimethod measurement of high-risk drinking locations: Extending the portal survey method with follow-up telephone interviews. Evaluation Review, 31(5), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X07303675

- Khalil, H., Peters, M. D., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Munn, Z. (2021). Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 130, 156–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.009

- Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Soares, C. B., & Parker, D. (2016). An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(2), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12144

- LaBrie, J. W., Hummer, J. F., Pedersen, E. R., Lac, A., & Chithambo, T. (2012). Measuring college students’ motives behind prepartying drinking: Development and validation of the prepartying motivations inventory. Addictive Behaviors, 37(8), 962–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.003

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5(1), 69–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lubman, D. I., Droste, N., Pennay, A., Hyder, S., & Miller, P. (2014). High rates of alcohol consumption and related harm at schoolies week: A portal study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38(6), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12266

- MacLean, S., & Callinan, S. (2013). fourteen dollars for one beer!" pre-drinking is associated with high-risk drinking among Victorian young adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 37(6), 579–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12138

- McClatchley, K., Shorter, G. W., & Chalmers, J. (2014). Deconstructing alcohol use on a night out in England: Promotions, preloading and consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(4), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12150

- McCreanor, T., Lyons, A., Moewaka Barnes, H., Hutton, F., Goodwin, I., & Griffin, C. (2016). drink a 12 box before you go’: Pre-loading among young people in Aotearoa New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 11(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2015.1037314

- Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H. F., Branner, A., Johnson, M., & Voas, R. (2013). Group influences on individuals’ drinking and other drug use at clubs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(2), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2013.74.280

- Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H., Branner, A., Voas, R., & Johnson, M. (2013). Assessment of club patrons’ alcohol and drug use the use of biological markers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.014

- Miller, B. A., Furr-Holden, C. D., Voas, R. B., & Bright, K. (2005). Emerging adults’ substance use and risky behaviors in club settings. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260503500207

- Miller, B. A., Furr-Holden, D., Johnson, M. B., Holder, H., Voas, R., & Keagy, C. (2009). Biological markers of drug use in the club setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.261

- Morrison, C., Lee, J. P., Gruenewald, P. J., & Marzell, M. (2015). A critical assessment of bias in survey studies using location-based sampling to recruit patrons in bars. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(11), 1427–1436. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.1018540

- Moser, K., Pearson, M. R., Hustad, J. T. P., & Borsari, B. (2014). Drinking games, tailgating, and pregaming: Precollege predictors of risky college drinking. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(5), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2014.936443

- O’Neil, A. I., Lafreniere, K. D., & Jackson, D. L. (2016). Pre-drinking motives in Canadian undergraduate students: Confirmatory factor analysis of the prepartying motivations inventory and examination of new themes. Addictive Behaviors, 60, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.024

- O’Rourke, S., Ferris, J., & Devaney, M. (2016). Beyond pre-loading: Understanding the associations between pre-, side- and back-loading drinking behavior and risky drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.008

- Østergaard, J., & Andrade, S. B. (2014). Who pre-drinks before a night out and why? Socioeconomic status and motives behind young people’s pre-drinking in the United Kingdom. Journal of Substance Use, 19(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2013.784368

- Palamar, J. J., Fitzgerald, N. D., Keyes, K. M., & Cottler, L. B. (2021). Drug checking at dance festivals: A review with recommendations to increase generalizability of findings. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000452

- Pedersen, E. R., & LaBrie, J. (2007). Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 56(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.3200/jach.56.3.237-246

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garritty, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O’Brien, K. K., Tunçalp, Ö., Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. (2021). Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Pilatti, A., & Read, J. P. (2018). Development and psychometric evaluation of a new measure to assess pregaming motives in Spanish-speaking young adults. Addictive Behaviors, 81, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.019

- Rajaseharan, D., & Dongre, A. (2021). Pregaming on alcohol products among male college students in puducherry-mixed-methods study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 46(3), 401–404. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_421_20

- Read, J. P., Merrill, J. E., & Bytschkow, K. (2010). Before the party starts: Risk factors and reasons for “pregaming” in college students. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 58(5), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480903540523

- Riordan, B. C., Conner, T. S., Flett, J., A. M., Droste, N., Cody, L., Brookie, K. L., Riordan, J. K., & Scarf, D. (2018). An intercept study to measure the extent to which New Zealand university students pre-game. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(1), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12754

- Ryan, J. E., Smeltzer, S. C., & Sharts-Hopko, N. C. (2019). Challenges to studying illicit drug users. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 51(4), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12486

- Santos, M. G. R., Paes, A. T., Sanudo, A., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2015). Factors associated with pre-drinking among nightclub patrons in the city of são paulo. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 50(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu055

- Santos, M. G. R., Paes, A. T., Sanudo, A., Andreoni, S., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2015). Gender differences in predrinking behavior among nightclubs’ patrons. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(7), 1243–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12756

- Sañudo, A., Andreoni, S., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2015). Polydrug use among nightclub patrons in a megacity: A latent class analysis. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(12), 1207–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.012

- Sorbello, J. G., Devilly, G. J., Allen, C., Hughes, L. R. J., & Brown, K. (2018). Fuel-cell breathalyser use for field research on alcohol intoxication: An independent psychometric evaluation. PeerJ, 6(3), e4418. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4418

- Stevely, A. K., Holmes, J., & Meier, P. S. (2020). Contextual characteristics of adults’ drinking occasions and their association with levels of alcohol consumption and acute alcohol-related harm: A mapping review. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 115(2), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14839

- Stevely, A. K., Holmes, J., McNamara, S., & Meier, P. S. (2020). Drinking contexts and their association with acute alcohol-related harm: A systematic review of event-level studies on adults’ drinking occasions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(4), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13042

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Van Geest, J. B., Johnson, T. P., & Alemagno, S. A. (2017). History of substance abuse research in the United States. In Research methods in the study of substance abuse (pp. 3–25). Springer.

- Voas, R. B., Furr-Holden, D., Lauer, E., Bright, K., Johnson, M. B., & Miller, B. (2006). Portal surveys of time-out drinking locations: A tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Evaluation Review, 30(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X05277285

- Voas, R. B., Johnson, M. B., & Miller, B. A. (2013). Alcohol and drug use among young adults driving to a drinking location. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(1-2), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.014

- Wagner, G. A., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2017). Patterns of drinking and driving offenses among nightclub patrons in Brazil. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 43, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.011

- Wells, S., Graham, K., & Purcell, J. (2009). Policy implications of the widespread practice of ‘pre-drinking’ or ‘pre-gaming’ before going to public drinking establishments - are current prevention strategies backfiring? Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02393.x

- Zamboanga, B. L., & Tomaso, C. C. (2014). Introduction to the special issue on college drinking games. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(5), 349–352. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2014.949728

- Zamboanga, B., & Olthuis, J. (2016). What is pregaming and how prevalent is it among US college students? An introduction to the special issue on pregaming. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(8), 953–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1187524