Abstract

Background: Societal beliefs about the seriousness of different addictions were assessed in the United Kingdom (UK). Methods: An online panel, conducted in 2021 and sampled to be representative of the UK general population 18 years and over (N = 1499), was conducted and asked participants their views regarding the seriousness of different societal problems, including various addictive behaviors. Results: Cannabis was ranked as the least serious of the addictive behaviors. Other illicit drug use (cocaine, amphetamine, heroin) was rated as the most serious of addictive behaviors. None of the addictive behaviors were rated as being as serious a problem to society as environmental damage, violent crime, poverty, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Conclusions: Ratings of cannabis use were not as expected and stand in contrast to the current UK policy on cannabis use. In addition, the UK policy on alcohol consumption contrasts with societal concerns about alcohol use.

Introduction

Public perceptions of addictive behaviors vary between countries (Hirschovits-Getz et al., 2011), and across periods within the same country (Cunningham & Koski-Jannes, Citation2019). These variations matter because the beliefs that people hold about different addictions determine how stigmatized different addictions are (Horch & Hodgins, Citation2008; Kilian et al., Citation2021; Morris et al., Citation2022a; Room, Citation2005; van Boekel et al., Citation2013) and impact how people believe addictive behaviors should be addressed (e.g., is treatment needed) (Cunningham et al., Citation1996, Citation2007; Morris et al., Citation2022b; Room, Citation1977). Societal beliefs about addiction may therefore influence policy decisions, for example, the war on drugs, the criminalization of cannabis, or the provision of publicly funded treatment.

A series of cross-national surveys were conducted in 2008 to compare societal views of the seriousness of addictions between Sweden, Finland, part of Russia, and Canada (Blomqvist, Citation2009; Blomqvist et al., Citation2014; Hirschovits-Getz et al., 2011; Holma et al., Citation2011; Koski-Jannes et al., Citation2012a, Citationb). Comparisons between these surveys revealed substantial differences in societal concerns about different addictions—with alcohol being regarded as one of society’s most serious problems in Finland compared to Canada and Sweden where alcohol was ranked as of lesser concern. Views on cannabis varied widely, with cannabis ranked as the least serious problem in Canada and of more concern in Sweden and Finland. This line of research was further expanded in 2016 with a comparison across European countries (Blomqvist et al., Citation2016) and a related study was conducted in Poland (Klingemann et al., Citation2017). Finally, this survey was repeated in Canada in 2018, primarily to examine changes in societal views resulting from the legalization of cannabis in that country. While there was a small increase observed regarding the seriousness of cannabis concerns, much larger increases were observed between 2008 and 2018 in public concern over the misuse of medical drugs and of other drugs like cocaine, amphetamines, or heroin (perhaps reflecting the emergence of the opioid epidemic) (Cunningham & Koski-Jannes, Citation2019). The current study will replicate this survey in the United Kingdom (UK) to gather data on societal views of addictive behaviors in this country.

Methods

An anonymous survey of participants (18 years and older) was recruited from the Prolific website. The study was advertised as a survey asking for people’s beliefs about alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. Potential participants were told that the survey would take 5–10 min to complete and that they would be paid £1.25 into their Prolific account. After reading the advertisement, participants who clicked on the link were taken to an information sheet/consent form. Those who agreed to participate were provided the survey.

The participants were selected using the Prolific method of sampling to be representative of the age, gender, and ethnic distribution of the UK based on 2011 Census data (Office for National Statistics, Citation2016). Further, because the resulting sample appeared skewed toward younger age groups, and in order to promote its similarity to the year the surveys was conducted (December, 2021), post-stratification weights were applied by age group and gender (male/female) using data from the Office of National Statistics estimate of the population for the United Kingdom in July of 2021 (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022; Royal, Citation2019). For participants who did not identify as male or females (n = 15), a weight of 1 was applied in order to retain these participants in the sample for analyses. Means and standard deviations are reported based on weighted values. Sample sizes are reported as unweighted samples.

2.1 survey content

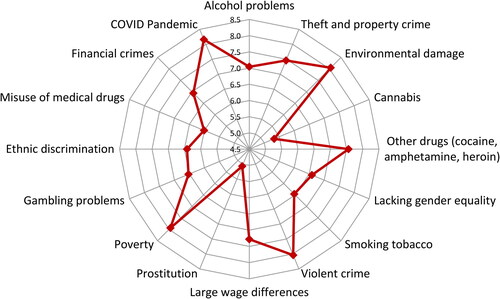

The survey started by asking participants how serious they thought a number of problems were for society (and to rate their seriousness on a scale from 1 to 10; see for a list of the items surveyed). Participants were told that by “problems,” we meant problems both for individuals and society as a whole and by “our society,” we meant people living in the United Kingdom. These items included questions about the use of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, gambling, the use of other drugs like cocaine, amphetamines, or heroin, and the misuse of prescription medicine. The first 15 items have been employed in previous research (Cunningham & Koski-Jannes, Citation2019; Hirschovits-Getz et al., 2011; Holma et al., Citation2011). One additional item was added at the end of the survey relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. An attention check item was nested in the middle of these questions (I want to indicate that I have read this question by checking 10) (Godinho et al., Citation2016). Those who answered the attention check question incorrectly were excluded from the analyses (but were still compensated for completing the survey).

Figure 1. Do you think the following are serious problems for our society? (1 = not at all serious; 10 = extremely serious).

The survey concluded with a series of questions asking about the participant’s demographic characteristics, including a question to confirm that they lived in the United Kingdom. In addition, participants were asked if they answered all questions truthfully (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Only participants who rated strongly agree were included in the analysis (all participants were paid whether they strongly agreed or not).

Finally, participants were provided with the link to the NHS website to seek additional information if they were concerned about their use of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or other drugs. After being provided with the brief description of the study, participants were provided with the option to have their data removed from the study and were be informed that their payment through the Prolific website would not be affected if they decided to remove their responses.

Results

A total of 1499 participants completed the UK survey. Of these, five did not agree to have their data used after the purpose of the study was explained at the end of the survey (n = 1494). An additional 56 participants did not strongly agree that they answered all the questions truthfully (n = 1438). Finally, two participants said that they did not live in the UK and an additional 14 participants did not answer the attention check correctly and were excluded from the analyses (N = 1422). presents a summary of the demographic characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

displays a radar diagram of the ratings of the perceived seriousness of different societal problems. As can be seen for the individual addictive behaviors, cannabis was ranked as the least serious of addictions problems. Other drug use (cocaine, amphetamine, heroin) was ranked as the most serious of addictive behaviors. The range of problem seriousness ratings in the UK was from 5.3 for cannabis to ratings slightly above 8 for environmental damage, violent crime, poverty, and the COVID pandemic.

displays the results of a principal component analysis with varimax rotation of the societal beliefs items. The data yielded three factors with eigenvalues of greater than one. The first factor contained all the addictive behavior items plus the item on prostitution. The second factor consisted of societal problems such as environmental damage, lacking gender equality, large wage differences and poverty. The third factor contained items for theft and property crime, and violent crime. The other drug use item (cocaine, amphetamine, heroin) loaded onto both factor one and factor three.

Table 2. Rotated principal components matrix of societal problems, factor loadings.

Discussion

In the UK in 2021, the issues rated as the most serious problems for society appear to be environmental damage, violent crime, poverty, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the social problems included in the survey, the various addictive behaviors did not appear to be regarded as seriously as items like environmental damage. Of the addictive behaviors, those rated as most serious were other drug use (cocaine, amphetamine, heroin) followed by alcohol. Cannabis use was regarded as the least serious societal problem out of all the addictive behaviors surveyed. Given that recreational cannabis use is illegal in the UK, and other addictive behaviors like alcohol use, tobacco use and gambling are legal, societal views regarding cannabis appear to contrast sharply with the current policy approach to addressing cannabis use in the UK. In addition, as alcohol use was regarded as a relatively serious problem, societal views on alcohol also seem to contrast with the policy approach in the UK. Finally, tobacco use and gambling were ranked as more serious than cannabis use but less serious than alcohol and other drug use.

Visual comparison of these findings with the 2018 Canadian survey (Cunningham & Koski-Jannes, Citation2019) indicated that, while the overall pattern of ratings between the two countries were similar, there were some notable differences in ratings of addictive behaviors. While ranked as the most serious of addictive behaviors in both countries, other drug use (cocaine, amphetamines, heroin) appeared to be regarded as a more serious problem in Canada than in the UK and was ranked as the most serious of all societal problems in Canada. Misuse of medical drugs was also rated higher in Canada than in the UK. These differences might reflect the ongoing opioid epidemic in Canada where the abuse of synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl, oxycodone) is more common than in the UK (Gardner et al., Citation2022; Office for National Statistics, Citation2020). Tobacco use and gambling appeared to have similar ratings of seriousness in the UK and in Canada, with both countries appearing to rank these addictive behaviors as more serious than cannabis use but less serious than alcohol and other drug use. Ratings regarding alcohol were very similar between the two countries. Finally, while both countries regard cannabis as the least serious addictive behavior of those surveyed, the UK participants may have rated cannabis use as a less serious societal problem than in Canada, where recreational cannabis use is now legal.

The results of the principal components analysis found that violent crime, theft, and property crime were loaded onto a separate factor than most of the addictive behaviors (the exception being other drug use such as cocaine, amphetamine, and heroin which loaded onto two factors). In the 2018 Canadian survey (Cunningham & Koski-Jannes, Citation2019), criminal activities and addictive behaviors loaded onto the same factor. Further research is merited to investigate whether there are societal differences in the degree to which people view addictions as criminal behaviors between Canada, the UK and in other countries.

There were a number of limitations with this research. Participants who sign up to complete online surveys, even when sampled to have equal numbers in different demographic categories as the general population, cannot be assumed to be equivalent to a sample who are proactively and randomly selected from the general population.

Conclusion

Cannabis use appears to be regarded as being relatively unlikely to cause problems for society. Other drug use (cocaine, amphetamine, heroin) is regarded as a serious societal problem while tobacco and alcohol use are ranked as less severe. This is despite the fact that tobacco and alcohol consumption remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality (Peacock et al., Citation2018). It appears that societal views of addictions may be more a reflection of familiarity with the addiction (i.e., alcohol and tobacco use are familiar to most people; heroin use is not) perhaps influenced by media depictions of the addiction (Blomqvist et al., Citation2014; Holma et al., Citation2011) rather than a reflection of the objective level of harm caused to society by the drug (Nutt et al., Citation2010; van Amsterdam et al., Citation2010). Further research is merited, both between countries with variations in the prevalence of different addictions and between those with different policies toward their use. This would allow us to gain insight into how societal beliefs about addictions might impact on both national policies regarding the use and treatment of addictions, and on stigma toward those engaging in different addictive behaviors (Kilian et al., Citation2021; Morris et al., Citation2022; Room, Citation2005).

Author contributions

Both authors have made an intellectual contribution to this research. JAC is the principal investigator, with overall responsibility for the project. He conceived the study and oversaw all aspects of the project. Both authors have contributed to the manuscript drafting process, have read, and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study received ethics approval from the REB of King’s College London. As this was an anonymous online panel survey, participants provided consent to participate by checking that they agreed to complete the study after reading an information sheet describing the research.

Acknowledgements

John Cunningham is supported by the Nat & Loretta Rothschild Chair in Addictions Treatment & Recovery Studies.

Disclosure statement

None to declare.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blomqvist, J. (2009). What is the worst thing you could get hooked on? Popular images of addiction problems in Sweden. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 26(4), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600404

- Blomqvist, J., Koski-Jännes, A., & Cunningham, J. (2014). How should substance use problems be handled? Popular views in Sweden, Finland, and Canada. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 14(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-09-2013-0040

- Blomqvist, J., Raitasalo, K., Melberg, H. O., Schreckenberg, D., Peschel, C., Klingemann, J., & Koski-Jannes, A. (2016). Popular images of addiction in five European countries. In M. Hellman, V. Berridge, K. Duke, & A. Mold (Eds.), Concepts of addictive substances and behaviours across time and place (pp. 193–212). Oxford University Press.

- Cunningham, J. A., Blomqvist, J., & Cordingley, J. (2007). Beliefs about drinking problems: Results from a general population telephone survey. Addictive Behaviors, 32(1), 166–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.011

- Cunningham, J. A., & Koski-Jännes, A. (2019). The last 10 years: Any changes in perceptions of the seriousness of alcohol, cannabis, and substance use in Canada? Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0243-0

- Cunningham, J. A., Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1996). Are disease and other conceptions of alcohol abuse related to beliefs about outcome and recovery. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(9), 773–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01129.x

- Gardner, E. A., McGrath, S. A., Dowling, D., & Bai, D. (2022). The opioid crisis: Prevalence and markets of opioids. Forensic Science Review, 34(1), 43–70.

- Godinho, A., Kushnir, V., & Cunningham, J. A. (2016). Unfaithful findings: Identifying careless responding in addictions research. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 111(6), 955–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13221

- Hirschovits-Gerz, T., Holma, K., Koski-Jännes, A., Raitasalo, K., Blomqvist, J., Cunningham, J. A., & Pervova, I. (2011). Is there something peculiar about Finnish views on alcohol addiction? A cross-cultural comparison between four Nordic populations. Finnish Journal of Social Research, 4, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.51815/fjsr.110704

- Holma, K., Koski-Jännes, A., Raitasalo, K., Blomqvist, J., Pervova, I., & Cunningham, J. A. (2011). Perceptions of addictions as societal problems in Canada, Sweden, Finland and St. Petersburg, Russia. European Addiction Research, 17(2), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323278

- Horch, J. D., & Hodgins, D. C. (2008). Public stigma of disordered gambling: Social distance, dangerousness, and familiarity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(5), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.5.505

- Kilian, C., Manthey, J., Carr, S., Hanschmidt, F., Rehm, J., Speerforck, S., & Schomerus, G. (2021). Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14598

- Klingemann, J. I., Klingemann, H., & Moskalewicz, J. (2017). Popular views on addictions and on prospects for recovery in Poland. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(13), 1765–1771. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1311347

- Koski-Jännes, A., Hirschovits-Gerz, T., & Pennonen, M. (2012a). Population, professional, and client support for different models of managing addictive behaviors. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(3), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.629708

- Koski-Jännes, A., Hirschovits-Gerz, T., Pennonen, M., & Nyyssönen, M. (2012b). Population, professional and client views on the dangerousness of addictions: Testing the familiarity hypothesis. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 29(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-012-0010-2

- Morris, J., Moss, A. C., Albery, I. P., & Heather, N. (2022a). The “alcoholic other”: Harmful drinkers resist problem recognition to manage identity threat. Addictive Behaviors, 124, 107093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107093

- Morris, J., Cox, S., Moss, A. C., & Reavey, P. (2022b). Drinkers like us? The availability of relatable drinking reduction narratives for people with alcohol use disorders. Addiction Research & Theory, 31(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2022.2099544

- Nutt, D. J., King, L. A., & Phillips, L. D, Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. (2010). Drug harms in the UK: A multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet (London, England), 376(9752), 1558–1565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6

- Office for National Statistics (2016). CT0570_2011 census - sex by age by IMD2004 by ethnic group. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/adhocs/005378ct05702011censussexbyagebyimd2004byethnicgroup

- Office for National Statistics (2020). Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2019 registrations. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2019registrations

- Office for National Statistics (2022). Estimates of the population for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland

- Peacock, A., Leung, J., Larney, S., Colledge, S., Hickman, M., Rehm, J., Giovino, G. A., West, R., Hall, W., Griffiths, P., Ali, R., Gowing, L., Marsden, J., Ferrari, A. J., Grebely, J., Farrell, M., & Degenhardt, L. (2018). Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 113(10), 1905–1926. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14234

- Room, R. (1977). Measurement and distribution of drinking patterns and problems in general populations. In G. Edwards, M. M. Gross, M. Keller, J. Moser, & R. Room (Eds.), Alcohol-related disabilities (pp. 62–87). World Health Organization.

- Room, R. (2005). Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24(2), 143–155. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16076584 https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230500102434

- Royal, K. D. (2019). Survey research methods: A guide for creating post-stratification weights to correct for sample bias. Education in the Health Professions, 2(1), 48–50. https://doi.org/10.4103/EHP.EHP_8_19

- van Amsterdam, J., Opperhuizen, A., Koeter, M., & van den Brink, W. (2010). Ranking the harm of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs for the individual and the population. European Addiction Research, 16(4), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317249

- van Boekel, L. C., Brouwers, E. P., van Weeghel, J., & Garretsen, H. F. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(1-2), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018